Hindu Kush

Coordinates: 35°N 71°E / 35°N 71°E

| Hindu Kush | |

|---|---|

Hindu Kush range | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Tirich Mir |

| Elevation | 7,708 m (25,289 ft) |

| Coordinates | 36°14′45″N 71°50′38″E / 36.24583°N 71.84389°E |

| Geography | |

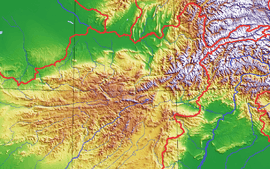

Topography of the Hindu Kush range (upper-right regions of the map) | |

| Countries | |

| Region | South-Central Asia |

| Parent range | Himalayas |

The Hindu Kush (/kʊʃ, kuːʃ/; Pashto, Persian and Urdu: هندوکش), also known in Ancient Greek as the Caucasus Indicus (Ancient Greek: Καύκασος Ινδικός) or Paropamisadae (Ancient Greek: Παροπαμισάδαι), is an 800-kilometre-long (500 mi) mountain range that stretches between central Afghanistan and northern Pakistan. It forms the western section of the Hindu Kush Himalayan Region (HKH).[1][2][3] It divides the valley of the Amu Darya (the ancient Oxus) to the north from the Indus River valley to the south.

The highest point in the Hindu Kush is Tirich Mir or Terichmir at 7,708 metres (25,289 ft) in the Chitral District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. To the east, the Hindu Kush buttresses the Pamir Mountains near the point where the borders of China, Pakistan and Afghanistan meet, after which it runs southwest through Pakistan and into Afghanistan, finally merging into minor ranges in central Afghanistan like the Koh-i Baba. The mountain range separates Central Asia from South Asia.[4]

Geology, the range's origin

The Hindu Kush began forming about 70 million years ago,[5] and marks the western end of the Hindu Kush to Himalayas mountain chain.[1] During the late Cretaceous Period, as the Indo-Australian Plate drove north into the Eurasian Plate, they formed a convergent boundary, resulting in the ongoing Himalayan orogeny.[6]

The Hindu Kush range is still rising;[7][8][9] the area is still geologically unstable and gets earthquakes.[10][11] See also October 2015 Hindu Kush earthquake and 2016 Afghanistan earthquake.

Origin of name

The origins of the name Hindu Kush are uncertain, with multiple theories being propounded by different scholars and writers. In the time of Alexander the Great, the Hindu Kush range was referred to as the Caucasus Indicus or the "Caucasus of the Indus River" (as opposed to the Greater Caucasus range between the Caspian and Black Seas), and some past authors have considered this as a possible derivation of the name Hindu Kush. Hindū Kūh (ھندوکوه, Hindu Mountain) and Kūh-e Hind (کوهِ ھند, Mountain of Hind) usually applied to the entire range separating the basins of the Kabul and Helmand Rivers from that of the Amu Darya, or, more specifically, to that part of the range lying northwest of Kabul.

The mountain range was also called "Paropamisadae" by Hellenic Greeks in the late first millennium BC.[12]

Some 19th century Encyclopedias and gazetteers state that the term Hindu Kush originally applied only to the peak in the area of the Kushan Pass, which had become a center of the Kushan Empire by the first century.[13][14][15][16]

The Persian-English dictionary[17] indicates that the word 'koš' [kʰoʃ] is derived from the verb ('koštan' کشتن [kʰoʃˈt̪ʰæn]), meaning to kill. Although the derivation is only a possible one, some authors, including Sanjeev Sanyal,[18] have proposed the meaning "Kills the Hindu" for "Hindu Kush", a derivation that is reproduced in Encyclopedia Americana which says that the name Hindu Kush means "kills the Hindu" and is a reminder of the days when slaves from the Indian subcontinent died in the harsh weather typical of the Afghan mountains while being transported to Central Asia.[19] The World Book Encyclopedia states that "the name Kush ... means Death".[20]

The word Koh or Kuh means "mountain" in a local language, Khowar. According to Nigel Allan, Hindu Kush meant both "mountains of India" and "sparkling snows of India", as he notes, from a Central Asian perspective.[21]

History

The mountains have historical significance in the Indian subcontinent and China. There has been a military presence in the mountains since the time of Darius the Great. The Great Game of the 19th century often involved military, intelligence and/or espionage personnel from both the Russian and British Empires operating in areas of the Hindu Kush. The Hindu Kush were considered, informally, the dividing line between Russian and British areas of influence in Afghanistan.

During the Cold War the mountains again became militarized, especially during the 1980s when Soviet forces and their Afghan allies fought the mujahideen. After the Soviet withdrawal, Afghan warlords fought each other and later the Taliban and the Northern Alliance and others fought in and around the mountains.

The American and ISAF campaign against Al Qaeda and their Taliban allies has once again resulted in a major military presence in the Hindu Kush.[22][23]

Alexander the Great explored the Afghan areas between Bactria and the Indus River after his conquest of the Achaemenid Empire in 330 BCE. It became part of the Seleucid Empire before falling to the Indian Maurya Empire around 305 BCE.

Alexander took these away from the Persians and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange 500 elephants.[24]— Strabo, 64 BCE–24 CE

Indo-Scythians expelled the Indo-Greeks by the mid 1st century BCE, but lost the area to the Kushan Empire about 100 years later.[25]

Before the Christian era, and afterwards, there was an intimate connection between the Kabul Valley and India. All the passes of the Hindu-Kush descend into that valley; and travellers from the north as soon as they crossed the watershed, found a civilization and religion, the same as that which prevailed in India. The great range was the boundary in those days and barrier that was at times impassable. Hindu-Kuh—the mountain of Hind—was similarly derived.

Pre-Islamic populations of the Hindu Kush included Shins, Yeshkun,[26] Chiliss, Neemchas[27] Koli,[28] Palus,[28] Gaware,[29] Yeshkuns,[30] Krammins,[30] Indo-Scythians, Bactrian Greeks, Kushans, and ancient Iranian Aryan Vedic Sanskrit tribes.

Mountains

The mountains of the Hindu Kush system diminish in height as they stretch westward: Toward the middle, near Kabul, they extend from 4,500 to 6,000 meters (14,800 to 19,700 ft); in the west, they attain heights of 3,500 to 4,000 meters (11,500 to 13,100 ft). The average altitude of the Hindu Kush is 4,500 meters (14,800 feet).[31]

The Hindu Kush system stretches about 966 kilometres (600 mi) laterally,[31] and its median north-south measurement is about 240 kilometres (150 mi). Only about 600 kilometres (370 mi) of the Hindu Kush system is called the Hindu Kush mountains. The rest of the system consists of numerous smaller mountain ranges including the Koh-i-Baba, Salang, Koh-e Paghman, Spin Ghar (also called the eastern Safēd Kōh), Suleiman Range, Siah Koh, Koh-e Khwaja Mohammad and Selseleh-e Band-e Turkestan. The western Safid Koh, the Malmand, Chalap Dalan, Siah Band and Doshakh are commonly referred to as the Paropamise by western scholars, though that name has been slowly falling out of use over the last few decades.

Rivers that flow from the mountain system include the Helmand River, the Hari River and the Kabul River, watersheds for the Sistan Basin.

Numerous high passes ("kotal") transect the mountains, forming a strategically important network for the transit of caravans. The most important mountain pass is the Salang Pass (Kotal-e Salang) (3,878 m); it links Kabul and points south of it to northern Afghanistan. The completion of a tunnel within this pass in 1964 reduced travel time between Kabul and the north to a few hours. Previously access to the north through the Kotal-e Shibar (3,260 m) took three days. The Salang tunnel at 3,363 m and the extensive network of galleries on the approach roads were constructed with Soviet financial and technological assistance and involved drilling 1.7 miles through the heart of the Hindu Kush.

Before the Salang road was constructed, the most famous passes in the Western historical perceptions of Afghanistan were those leading to India. They include the Khyber Pass (1,027 m), in Pakistan, and the Kotal-e Lataband (2,499 m) east of Kabul, which was superseded in 1960 by a road constructed within the Kabul River's most spectacular gorge, the Tang-e Gharu. This remarkable engineering feat reduced travel time between Kabul and the Pakistan border from two days to a few hours.

- Lataband Road

The roads through the Salang and Tang-e Gharu passes played critical strategic roles during the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and were used extensively by heavy military vehicles. Consequently, these roads are in very bad repair. Many bombed out bridges have been repaired, but numbers of the larger structures remain broken. Periodic closures due to conflicts in the area seriously affect the economy and well-being of many regions, for these are major routes carrying commercial trade, emergency relief and reconstruction assistance supplies destined for all parts of the country.

There are a number of other important passes in Afghanistan. The Wakhjir Pass (4,923 m), proceeds from the Wakhan Corridor into Xinjiang, China, and into Northern Areas of Pakistan. Passes which join Afghanistan to Chitral, Pakistan, include the Baroghil (3,798 m) and the Kachin (5,639 m), which also cross from the Wakhan. Important passes located farther west are the Shotorgardan (3,720 m), linking Logar and Paktiya provinces; the Bazarak (2,713 m), leading into Mazari Sharif; the Khawak Pass (4,370 m) in the Panjsher Valley, and the Anjuman Pass (3,858 m) at the head of the Panjsher Valley giving entrance to the north. The Hajigak (2,713 m) and Unai (3,350 m) lead into the eastern Hazarajat and Bamyan Valley. The passes of the Paropamisus in the west are relatively low, averaging around 600 meters; the most well-known of these is the Sabzak between the Herat and Badghis provinces, which links the western and northwestern parts of Afghanistan.

These mountainous areas are mostly barren, or at the most sparsely sprinkled with trees and stunted bushes. Very ancient mines producing lapis lazuli are found in Kowkcheh Valley, while gem-grade emeralds are found north of Kabul in the valley of the Panjsher River and some of its tributaries. The famous 'balas rubies', or spinels, were mined until the 19th century in the valley of the Ab-e Panj or Upper Amu Darya River, considered to be the meeting place between the Hindu Kush and the Pamir ranges. These mines now appear to be exhausted.

Eastern Hindu Kush

The Eastern Hindu Kush range, also known as the High Hindu Kush range, is mostly located in northern Pakistan and the Nuristan and Badakhshan provinces of Afghanistan. The Chitral District of Pakistan is home to Tirich Mir, Noshaq, and Istoro Nal, the highest peaks in the Hindu Kush. The range also extends into Ghizar, Yasin Valley, and Ishkoman in Pakistan's Northern Areas.

Chitral is considered to be the pinnacle of the Hindu Kush region. The highest peaks, as well as countless passes and massive glaciers, are located in this region. The Chiantar, Kurambar, and Terich glaciers are amongst the most extensive in the Hindu Kush and the meltwater from these glaciers form the Kunar River, which eventually flows south into Afghanistan and joins the Bashgal, Panjshir, and eventually the much smaller Kabul River.

Highest mountains

| Name | Height in [m] | Country |

|---|---|---|

| Tirich Mir | 7708 | PK |

| Noshak | 7492 | AF, PK |

| Istor-o-Nal | 7403 | PK |

| Saraghrar | 7338 | PK |

| Udren Zom | 7140 | PK |

| Lunkho e Dosare | 6901 | AF, PK |

| Kuh-e Bandaka | 6843 | AF |

| Koh-e Keshni Khan | 6743 | AF |

| Sakar Sar | 6272 | AF, PK |

| Kohe Mondi | 6234 | AF |

| Mīr Samīr | 5809 | AF |

See also

- Mount Imeon

- Paropamisus Mountains

- Himalayas

- A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush

- Geography of Afghanistan

- Geography of Pakistan

- Hindustan

- List of highest mountains (a list of mountains above 7,200m)

- List of mountain ranges

- 2002 Hindu Kush earthquakes

- 2005 Hindu Kush earthquake

References

- 1 2 "Hindu Kush Himalayan Region". ICIMOD. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ↑ "Mapping the vulnerability hotspots over Hindu-Kush Himalaya region to flooding disasters". Weather and Climate Extremes. 8: 46–58. doi:10.1016/j.wace.2014.12.001. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- ↑ "Development of an ASSESSment system to evaluate the ecological status of rivers in the Hindu Kush-Himalayan region" (PDF). assess-hkh.at. Retrieved 2015-09-06.

- ↑ "Hindu Kush mountains". Britannica. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Vogelsang, Willem (2002). The Afghans. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-19841-5. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ 1890,1896 Encyclopedia Brittanica s.v. "Afghanistan", Vol I p.228.

- ↑ 1893, 1899 Johnson's Universal Encyclopedia Vol I p.61.

- ↑ 1885 Imperial Gazetteer of India, V. I p. 30.

- ↑ 1850 A Gazetteer of the World Vol I p. 62.

- ↑ Boyle, J.A. (1949). A Practical Dictionary of the Persian Language. Luzac & Co. p. 129.

- ↑ Sanyal, Sanjeev (2012). Land of the Seven Rivers: A Brief History of India's Geography. Penguin Books, India. ISBN 9780670086399.

- ↑ Encyclopedia Americana. 14. 1993. p. 206.

- ↑ The World Book Encyclopedia. 19. 1990. p. 237.

- ↑ Allan, Nigel (2001). "Defining Place and People in Afghanistan". Post Soviet Geography and Economics. 8. 42: 545–560.

- ↑ A Short March to the Hindu Kush, Alpinist 18.

- ↑ "Alexander in the Hindu Kush". Livius. Articles on Ancient History. Retrieved 2007-09-12.

- ↑ Nancy Hatch Dupree / Aḥmad ʻAlī Kuhzād (1972). "An Historical Guide to Kabul - The Name". American International School of Kabul. Retrieved 2010-09-18.

- ↑ Houtsma, Martijn Theodoor (1987). E.J. Brill's first encyclopaedia of Islam, 1913–1936. 2. BRILL. p. 159. ISBN 90-04-08265-4. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Biddulph, p.38

- ↑ Biddulph, p.7

- 1 2 Biddulph, p.9

- ↑ Biddulph, p.11

- 1 2 Biddulph, p.12

- 1 2 Scott-Macnab, David (1994). On the roof of the world. London: Reader's Digest Assiciation Ldt. p. 22.

Bibliography

- Biddulph, John. Tribes of the Hindoo Koosh (Sang-e-Meel, 2001)

Further reading

- Drew, Frederic (1877). The Northern Barrier of India: A Popular Account of the Jammoo and Kashmir Territories with Illustrations. Frederic Drew. 1st edition: Edward Stanford, London. Reprint: Light & Life Publishers, Jammu, 1971

- Gibb, H. A. R. (1929). Ibn Battūta: Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325–1354. Translated and selected by H. A. R. Gibb. Reprint: Asian Educational Services, New Delhi and Madras, 1992

- Gordon, T. E. (1876). The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the High Plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus Sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Tapei, 1971

- Leitner, Gottlieb Wilhelm (1890). Dardistan in 1866, 1886 and 1893: Being An Account of the History, Religions, Customs, Legends, Fables and Songs of Gilgit, Chilas, Kandia (Gabrial) Yasin, Chitral, Hunza, Nagyr and other parts of the Hindukush, as also a supplement to the second edition of The Hunza and Nagyr Handbook. And An Epitome of Part III of the author's 'The Languages and Races of Dardistan'. Reprint, 1978. Manjusri Publishing House, New Delhi. ISBN 81-206-1217-5

- Newby, Eric. (1958). A Short Walk in the Hindu Kush. Secker, London. Reprint: Lonely Planet. ISBN 978-0-86442-604-8

- Yule, Henry and Burnell, A. C. (1886). Hobson-Jobson: The Anglo-Indian Dictionary. 1996 reprint by Wordsworth Editions Ltd. ISBN 1-85326-363-X

- A Country Study: Afghanistan, Library of Congress

- Hindu Kush at Encyclopædia Iranica

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15 th Ed, Vol.21, pp. 54–55, 1987

- An Advanced History of India, by R. C. Majumdar, H. C. Raychaudhuri, K.Datta, 2nd Ed., MacMillan and Co, London, pp. 336–37, 1965

- Encyclopædia Britannica, 15 th Ed, Vol.21, p. 65, 1987

- The Cambridge History of India, Vol.IV - The Mughul Period, by W.Haig & R.Burn, S.Chand & Co., New Delhi, pp. 98–99, 1963

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Hindu Kush. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hindu Kush. |