Syria

Coordinates: 35°N 38°E / 35°N 38°E

| Syrian Arab Republic الجمهورية العربية السورية al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: "حماة الديار" (Arabic) Humat ad-Diyar Guardians of the Homeland |

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

_-_SYR_-_UNOCHA.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Damascus 33°30′N 36°18′E / 33.500°N 36.300°E | |||||

| Official languages | Arabic | |||||

| Ethnic groups | ||||||

| Government | Unitary dominant-party[upper-alpha 1] semi-presidential republic[1] | |||||

| • | President | Bashar al-Assad | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Imad Khamis | ||||

| • | Speaker of the People's Council | Hadiya Khalaf Abbas | ||||

| Legislature | People's Council | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| • | Proclamation of Arab Kingdom of Syria | 8 March 1920 | ||||

| • | State of Syria established under French Mandate | 1 December 1924 | ||||

| • | Syrian Republic established by merger of States of Jabal Druze, Alawites and Syria | 1930 | ||||

| • | Independence (Joint UN / French Mandate ended) | 24 October 1945 | ||||

| • | Last French troops leave |

17 April 1946 | ||||

| • | Secession from the United Arab Republic |

28 September 1961 | ||||

| • | Ba'ath party takes power |

8 March 1963 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 185,180[2] km2 (89th) 71,479 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 1.1 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | July 2014 estimate | 17,064,854[3] (54th) | ||||

| • | Density | 118.3/km2 (101st) 306.5/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $107.831 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $5,040[4] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2010 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $59.957 billion[4] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $2,802[4] | ||||

| Gini (2014) | 55.8[5] high |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | medium · 134th |

|||||

| Currency | Syrian pound (SYP) | |||||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +963 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | SY | |||||

| Internet TLD | .sy سوريا. |

|||||

|

||||||

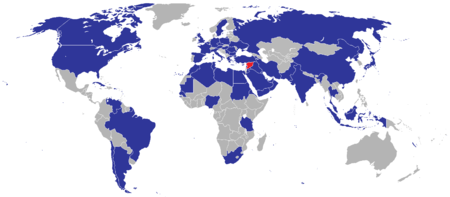

Syria (![]() i/ˈsɪ.rɪə/; Arabic: سوريا Sūriyā), officially known as the Syrian Arab Republic (Arabic: الجمهورية العربية السورية al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest. Syria's capital and largest city is Damascus.

i/ˈsɪ.rɪə/; Arabic: سوريا Sūriyā), officially known as the Syrian Arab Republic (Arabic: الجمهورية العربية السورية al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a country in Western Asia, bordering Lebanon and the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to the north, Iraq to the east, Jordan to the south, and Israel to the southwest. Syria's capital and largest city is Damascus.

A country of fertile plains, high mountains, and deserts, Syria is home to diverse ethnic and religious groups, including Syrian Arabs, Greeks, Armenians, Assyrians, Kurds, Circassians,[7] Mandeans[8] and Turks. Religious groups include Sunnis, Christians, Alawites, Druze, Mandeans, Shiites, Salafis, and Yazidis. Sunni Arabs make up the largest population group in Syria.

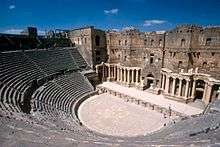

In English, the name "Syria" was formerly synonymous with the Levant (known in Arabic as al-Sham), while the modern state encompasses the sites of several ancient kingdoms and empires, including the Eblan civilization of the 3rd millennium BC. Its capital Damascus and largest city Aleppo are among the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world.[9] In the Islamic era, Damascus was the seat of the Umayyad Caliphate and a provincial capital of the Mamluk Sultanate in Egypt.

The modern Syrian state was established after the end of centuries of Ottoman control in World War I as a French mandate, and represented the largest Arab state to emerge from the formerly Ottoman-ruled Arab Levant. It gained independence as a parliamentary republic on 24 October 1945 when Syria became a founding member of the United Nations, an act which legally ended the former French Mandate – although French troops did not leave the country until April 1946. The post-independence period was tumultuous, and a large number of military coups and coup attempts shook the country in the period 1949–71. In 1958, Syria entered a brief union with Egypt called the United Arab Republic, which was terminated by the 1961 Syrian coup d'état. The Arab Republic of Syria came into being in late 1961 after December 1 constitutional referendum, and was increasingly unstable until the Ba'athist coup d'état, since which the Ba'ath Party has maintained its power. Syria was under Emergency Law from 1963 to 2011, effectively suspending most constitutional protections for citizens. Bashar al-Assad has been president since 2000 and was preceded by his father Hafez al-Assad, who was in office from 1970 to 2000.[10]

Syria is a member of one international organization other than the United Nations, the Non-Aligned Movement; it has become suspended from the Arab League on November 2011[11] and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation,[12] and self-suspended from the Union for the Mediterranean.[13] Since March 2011, Syria has been embroiled in an uprising against Assad and the Ba'athist government as part of the Arab Spring, a crackdown that contributed to the Syrian Civil War and to Syria's becoming one of the most violent countries in the world.[14] A number of pseudo-state entities have since emerged on Syrian territories, including the Syrian Opposition, the Federation of Northern Syria and Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant.

Etymology

The name Syria is derived from the 8th century BC Luwian term "Sura/i", and the derivative ancient Greek name: Σύριοι, Sýrioi, or Σύροι, Sýroi, both of which originally derived from Aššūrāyu (Assyria) in northern Mesopotamia.[15][16] However, from the Seleucid Empire (323–150 BC), this term was also applied to The Levant, and from this point the Greeks applied the term without distinction between the Assyrians of Mesopotamia and Arameans of the Levant.[17][18] Mainstream modern academic opinion strongly favours the argument that the Greek word is related to the cognate Ἀσσυρία, Assyria, ultimately derived from the Akkadian Aššur.[19] In the past, others believed that it was derived from Siryon, the name that the Sidonians gave to Mount Hermon.[20] However, the discovery of the Çineköy inscription in 2000 seems to support the theory that the term Syria derives from Assyria, whose ancient homeland was located in modern northern Iraq.

The area designated by the word has changed over time. Classically, Syria lies at the eastern end of the Mediterranean, between Arabia to the south and Asia Minor to the north, stretching inland to include parts of Iraq, and having an uncertain border to the northeast that Pliny the Elder describes as including, from west to east, Commagene, Sophene, and Adiabene.[21]

By Pliny's time, however, this larger Syria had been divided into a number of provinces under the Roman Empire (but politically independent from each other): Judaea, later renamed Palaestina in AD 135 (the region corresponding to modern-day Israel, the Palestinian Territories, and Jordan) in the extreme southwest; Phoenice (established in 194 AD) corresponding to modern Lebanon, Damascus and Homs regions; Coele-Syria (or "Hollow Syria") south of the Eleutheris river, and Iraq.[22]

History

Ancient antiquity

Since approximately 10,000 BC, Syria was one of centers of Neolithic culture (known as Pre-Pottery Neolithic A) where agriculture and cattle breeding appeared for the first time in the world. The following Neolithic period (PPNB) is represented by rectangular houses of Mureybet culture. At the time of the pre-pottery Neolithic, people used vessels made of stone, gyps and burnt lime (Vaisselle blanche). Finds of obsidian tools from Anatolia are evidences of early trade relations. Cities of Hamoukar and Emar played an important role during the late Neolithic and Bronze Age. Archaeologists have demonstrated that civilization in Syria was one of the most ancient on earth, perhaps preceded by only those of Mesopotamia.

Eblaites and Amorites

The earliest recorded indigenous civilisation in the region was the Kingdom of Ebla[24] near present-day Idlib, northern Syria. Ebla appears to have been founded around 3500 BC,[25][26][27][28][29] and gradually built its fortune through trade with the Mesopotamian states of Sumer, Assyria and Akkad, as well as with the Hurrian and Hattian peoples to the northwest, in Asia Minor.[30] Gifts from Pharaohs, found during excavations, confirm Ebla's contact with Egypt.

One of the earliest written texts from Syria is a trading agreement between Vizier Ibrium of Ebla and an ambiguous kingdom called Abarsal c. 2300 BC.[31][32] Scholars believe the language of Ebla to be among the oldest known written Semitic languages after Akkadian, Recent classifications of the Eblaite language have shown that it was an East Semitic language, closely related to the Akkadian language.[33]

Ebla was weakened by a long war with Mari, and the whole of Syria became part of the Mesopotamian Akkadian Empire after Sargon of Akkad and his grandson Naram-Sin's conquests ended Eblan domination over Syria in the first half of the 23rd century BC.[34][35]

By the 21st century BC, Hurrians settled the northern east parts of Syria while the rest of the region was dominated by the Amorites, Syria was called the Land of the Amurru (Amorites) by their Assyro-Babylonian neighbors. The Northwest Semitic language of the Amorites is the earliest attested of the Canaanite languages. Mari reemerged during this period, and saw renewed prosperity until conquered by Hammurabi of Babylon. Ugarit also arose during this time, circa 1800 BC, close to modern Latakia. Ugaritic was a Semitic language loosely related to the Canaanite languages, and developed the Ugaritic alphabet.[36] the Ugarites kingdom survived until its destruction at the hands of the marauding Indo-European Sea Peoples in the 12th century BC.

Yamhad (modern Aleppo) dominated northern Syria for two centuries,[37] although Eastern Syria was occupied in the 19th and 18th centuries BC by the Old Assyrian Empire ruled by the Amorite Dynasty of Shamshi-Adad I, and by the Babylonian Empire which was founded by Amorites. Yamhad was described in the tablets of Mari as the mightiest state in the near east and as having more vassals than Hammurabi of Babylon.[37] Yamhad imposed its authority over Alalakh,[38] Qatna,[39] the Hurrians states and the Euphrates Valley down to the borders with Babylon.[40] The army of Yamhad campaigned as far away as Dēr on the border of Elam (modern Iran).[41] Yamhad was conquered and destroyed, along with Ebla, by the Indo-European Hittites from Asia Minor circa 1600 BC.[42]

From this time, Syria became a battle ground for various foreign empires, these being the Hittite Empire, Mitanni Empire, Egyptian Empire, Middle Assyrian Empire, and to a lesser degree Babylonia. The Egyptians initially occupied much of the south, while the Hittites, and the Mitanni, much of the north. However, Assyria eventually gained the upper hand, destroying the Mitanni Empire and annexing huge swathes of territory previously held by the Hittites and Babylon.

Arameans and Phoenicians

Around the 14th century BC, various Semitic peoples appeared in the area, such as the semi-nomadic Suteans who came into an unsuccessful conflict with Babylonia to the east, and the West Semitic speaking Arameans who subsumed the earlier Amorites. They too were subjugated by Assyria and the Hittites for centuries. The Egyptians fought the Hittites for control over western Syria; the fighting reached its zenith in 1274 BC with the Battle of Kadesh.[43][44] The west remained part of the Hittite empire until its destruction c. 1200 BC,[45] while eastern Syria largely became part of the Middle Assyrian Empire,[46] who also annexed much of the west during the reign of Tiglath-Pileser I 1114–1076 BC.

With the destruction of the Hittites and the decline of Assyria in the late 11th century BC, the Aramean tribes gained control of much of the interior, founding states such as Bit Bahiani, Aram-Damascus, Hamath, Aram-Rehob, Aram-Naharaim, and Luhuti. From this point, the region became known as Aramea or Aram. There was also a synthesis between the Semitic Arameans and the remnants of the Indo-European Hittites, with the founding of a number of Syro-Hittite states centered in north central Aram (Syria) and south central Asia Minor (modern Turkey), including Palistin, Carchemish and Sam'al.

A Canaanite group known as the Phoenicians came to dominate the coasts of Syria, (and also Lebanon and northern Palestine) from the 13th century BC, founding city states such as Amrit, Simyra, Arwad, Paltos, Ramitha and Shuksi. From these coastal regions they eventually spread their influence throughout the Mediterranean, including building colonies in Malta, Sicily, the Iberian peninsula (modern Spain and Portugal), the coasts of North Africa, and most significantly, founding the major city state of Carthage (in modern Tunisia) in the 9th century BC which was much later to become the center of a major empire, rivaling the Roman Empire.

Syria and the entire Near East and beyond then fell to the vast Neo Assyrian Empire (911 BC – 605 BC). The Assyrians introduced Imperial Aramaic as the lingua franca of their empire. This language was to remain dominant in Syria and the entire Near East until after the Arab Islamic conquest in the 7th and 8th centuries AD, and was to be a vehicle for the spread of Christianity. The Assyrians named their colonies of Syria and Lebanon Eber-Nari. Assyrian domination ended after the Assyrians greatly weakened themselves in a series of brutal internal civil wars, followed by an attacking coalition of their former subject peoples; the Medes, Babylonians, Chaldeans, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. During the fall of Assyria, the Scythians ravaged and plundered much of Syria. The last stand of the Assyrian army was at Carchemish in northern Syria in 605 BC.

The Assyrian Empire was followed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire (605 BC – 539 BC). During this period, Syria became a battle ground between Babylonia and another former Assyrian colony, that of Egypt. The Babylonians, like their Assyrian relations, were victorious over Egypt.

Classical antiquity

The Achaemenid Persians took Syria from Babylonia as part of their hegemony of Southwest Asia in 539 BC. The Persians, having spent four centuries under Assyrian rule, retained Imperial Aramaic as diplomatic language in the Achaemenid Empire (539 BC- 330 BC), and also the Assyrian name of the satrapy of Aram/Syria Eber-Nari.

Syria was conquered by the Greek Macedonian Empire, ruled by Alexander the Great circa 330 BC, and consequently became Coele-Syria province of the Greek Seleucid Empire (323 BC – 64 BC).

It was the Greeks who introduced the name "Syria" to the region. Originally an Indo-European corruption of "Assyria" in northern Mesopotamia, the Greeks used this term to describe not only Assyria itself but also the lands to the west which had for centuries been under Assyrian dominion.[47] Thus in the Greco-Roman world both the Arameans of Syria and the Assyrians of Mesopotamia to the east were referred to as "Syrians" or "Syriacs", despite these being distinct peoples in their own right, a confusion which would continue into the modern world. Eventually parts of southern Seleucid Syria were taken by Judean Hasmoneans upon the slow disintegration of the Hellenistic Empire.

Syria briefly came under Armenian control from 83 BC, with the conquests of Tigranes the Great, who was welcomed as a savior from the Seleucids and Romans by its people. The Armenians retained control of Syria for two decades before being driven out by the Romans.

Pompey the Great of the Roman Empire, who captured Antioch in 64 BC, turning Syria into a Roman province.

Palmyra, a rich and sometimes powerful native Aramaic-speaking kingdom arose in northern Syria in the 2nd century; the Palmyrene established a trade network that made the city one of the richest in the Roman empire. Eventually, in the late 3rd century AD, the Palmyrene king Odaenathus defeated the Persian emperor Shapur I and controlled the entirety of the Roman East while his successor and widow Zenobia established the Palmyrene Empire, which briefly conquered Egypt, Syria, Palestine, much of Asia Minor, Judah and Lebanon, before being finally brought under Roman control in 273 AD.

The northern Mesopotamian Assyrian kingdom of Adiabene controlled areas of north east Syria between 10 AD and 117 AD, before it was conquered by Rome.[48]

The Aramaic language has been found as far afield as Hadrians Wall in Ancient Britain, with inscriptions written by Assyrian and Aramean soldiers of the Roman Empire.[49]

Control of Syria eventually passed from the Romans to the Byzantines, with the split in the Roman Empire.[30]

The largely Aramaic-speaking population of Syria during the heyday of the Byzantine empire was probably not exceeded again until the 19th century. Prior to the Arab Islamic Conquest in the 7th century AD, the bulk of the population were Arameans, but Syria was also home to Greek and Roman ruling classes, Assyrians still dwelt in the north east, Phoenicians along the coasts, and Jewish and Armenian communities was also extant in major cities, with Nabateans and pre-Islamic Arabs such as the Lakhmids and Ghassanids dwelling in the deserts of southern Syria. Syriac Christianity had taken hold as the major religion, although others still followed Judaism, Mithraism, Manicheanism, Greco-Roman Religion, Canaanite Religion and Mesopotamian Religion. Syria's large and prosperous population made Syria one of the most important of the Roman and Byzantine provinces, particularly during the 2nd and 3rd centuries (AD).[50]

The Roman Emperor Alexander Severus, who was emperor from 222 to 235, was an Aramean from Syria. His cousin Elagabalus, who was emperor from 218 to 222, was also from Syria and his family held hereditary rights to the high priesthood of the Aramean sun god El-Gabal at Emesa (modern Homs) in Syria. Another Roman emperor who was a Syrian was Philip the Arab (Marcus Julius Philippus), emperor from 244 to 249.[50]

Syria is significant in the history of Christianity; Saulus of Tarsus, better known as the Apostle Paul, was converted on the Road to Damascus and emerged as a significant figure in the Christian Church at Antioch in ancient Syria, from which he left on many of his missionary journeys. (Acts 9:1–43)

Middle Ages

During Muhammad's era

Muhammad's first interaction with the people and tribes of Syria was during the Invasion of Dumatul Jandal in July 626 [51] where he ordered his followers to Invade Duma, because Muhammad received intelligence that some tribes there were involved in highway robbery and preparing to attack Medina itself.[52]

William Montgomery Watt claims that this was the most significant expedition Muhammad ordered at the time, even though it received little notice in the primary sources. Dumat Al-Jandal was 800 kilometres (500 mi) from Medina, and Watt says that there was no immediate threat to Muhammad, other than the possibility that his communications to Syria and supplies to Medina being interrupted. Watt says "It is tempting to suppose that Muhammad was already envisaging something of the expansion which took place after his death", and that the rapid march of his troops must have "impressed all those who heard of it".[53]

William Muir also believes that the expedition was important as Muhammad followed by 1000 men reached the confines of Syria, where distant tribes had now learnt his name, while the political horizon of Muhammad was extended.[51]

Islamic Syria (al-Sham)

By AD 640, Syria was conquered by the Arab Rashidun army led by Khalid ibn al-Walid. In the mid-7th century, the Umayyad dynasty, then rulers of the empire, placed the capital of the empire in Damascus. The country's power declined during later Umayyad rule; this was mainly due to totalitarianism, corruption and the resulting revolutions. The Umayyad dynasty was then overthrown in 750 by the Abbasid dynasty, which moved the capital of empire to Baghdad.

Arabic – made official under Umayyad rule – became the dominant language, replacing Greek and Aramaic of the Byzantine era. In 887, the Egypt-based Tulunids annexed Syria from the Abbasids, and were later replaced by once the Egypt-based Ikhshidids and still later by the Hamdanids originating in Aleppo founded by Sayf al-Dawla.[54]

Crusaders, Ayubids, Mamluks and Nizaris

Sections of Syria were held by French, English, Italian and German overlords between 1098 and 1189 AD during the Crusades and were known collectively as the Crusader states among which the primary one in Syria was the Principality of Antioch. The coastal mountainous region was also occupied in part by the Nizari Ismailis, the so-called Assassins, who had intermittent confrontations and truces with the Crusader States. Later in history when "the Nizaris faced renewed Frankish hostilities, they received timely assistance from the Ayyubids."[55]

After a century of Seljuk rule, Syria was largely conquered (1175–1185) by the Kurdish warlord Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt. Aleppo fell to the Mongols of Hulegu in January 1260, and Damascus in March, but then Hulegu was forced to break off his attack to return to China to deal with a succession dispute.

A few months later, the Mamluks arrived with an army from Egypt and defeated the Mongols in the Battle of Ain Jalut in Galilee. The Mamluk leader, Baibars, made Damascus a provincial capital. When he died, power was taken by Qalawun. In the meantime, an emir named Sunqur al-Ashqar had tried to declare himself ruler of Damascus, but he was defeated by Qalawun on 21 June 1280, and fled to northern Syria. Al-Ashqar, who had married a Mongol woman, appealed for help from the Mongols. The Mongols of the Ilkhanate took the city, but Qalawun persuaded Al-Ashqar to join him, and they fought against the Mongols on 29 October 1281, in the Second Battle of Homs, which was won by the Mamluks.[56]

In 1400, the Muslim Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur Lenk (Tamurlane) invaded Syria, sacked Aleppo and captured Damascus after defeating the Mamluk army. The city's inhabitants were massacred, except for the artisans, who were deported to Samarkand. Timur-Lenk also conducted specific massacres of the Aramean and Assyrian Christian populations, greatly reducing their numbers.[57][58] By the end of the 15th century, the discovery of a sea route from Europe to the Far East ended the need for an overland trade route through Syria.

Ottoman Syria

_1803.jpg)

_(cropped).jpg)

In 1516, the Ottoman Empire invaded the Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt, conquering Syria, and incorporating it into its empire. The Ottoman system was not burdensome to Syrians because the Turks respected Arabic as the language of the Quran, and accepted the mantle of defenders of the faith. Damascus was made the major entrepot for Mecca, and as such it acquired a holy character to Muslims, because of the beneficial results of the countless pilgrims who passed through on the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca.[59]

Ottoman administration followed a system that led to peaceful coexistence. Each ethno-religious minority – Arab Shia Muslim, Arab Sunni Muslim, Aramean-Syriac Orthodox, Greek Orthodox, Maronite Christians, Assyrian Christians, Armenians, Kurds and Jews – constituted a millet.[60] The religious heads of each community administered all personal status laws and performed certain civil functions as well.[59] In 1831, Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt renounced his loyalty to the Empire and overran Ottoman Syria, capturing Damascus. His short-term rule over the domain attempted to change the demographics and social structure of the region: he brought thousands of Egyptian villagers to populate the plains of Southern Syria, rebuilt Jaffa and settled it with veteran Egyptian soldiers aiming to turn it into a regional capital, and he crushed peasant and Druze rebellions and deported non-loyal tribesmen. By 1840, however, he had to surrender the area back to the Ottomans.

From 1864, Tanzimat reforms were applied on Ottoman Syria, carving out the provinces (vilayets) of Aleppo, Zor, Beirut and Damascus Vilayet; Mutasarrifate of Mount Lebanon was created, as well, and soon after the Mutasarrifate of Jerusalem was given a separate status.

During World War I, the Ottoman Empire entered the conflict on the side of Germany and the Austro-Hungarian Empire. It ultimately suffered defeat and loss of control of the entire Near East to the British Empire and French Empire. During the conflict, genocide against indigenous Christian peoples was carried out by the Ottomans and their allies in the form of the Armenian Genocide and Assyrian Genocide, of which Deir ez-Zor, in Ottoman Syria, was the final destination of these death marches.[61] In the midst of World War I, two Allied diplomats (Frenchman François Georges-Picot and Briton Mark Sykes) secretly agreed on the post-war division of the Ottoman Empire into respective zones of influence in the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916. Initially, the two territories were separated by a border that ran in an almost straight line from Jordan to Iran. However, the discovery of oil in the region of Mosul just before the end of the war led to yet another negotiation with France in 1918 to cede this region to 'Zone B', or the British zone of influence. This border was later recognized internationally when Syria became a League of Nations mandate in 1920[62] and has not changed to date.

French Mandate

In 1920, a short-lived independent Kingdom of Syria was established under Faisal I of the Hashemite family. However, his rule over Syria ended after only a few months, following the Battle of Maysalun. French troops occupied Syria later that year after the San Remo conference proposed that the League of Nations put Syria under a French mandate. General Gouraud had according to his secretary de Caix two options: "Either build a Syrian nation that does not exist... by smoothing the rifts which still divide it" or "cultivate and maintain all the phenomena, which require our abitration that these divisions give". De Caix added "I must say only the second option interests me". This is what Gouraud did.[63][64]

In 1925, Sultan al-Atrash led a revolt that broke out in the Druze Mountain and spread to engulf the whole of Syria and parts of Lebanon. Al-Atrash won several battles against the French, notably the Battle of al-Kafr on 21 July 1925, the Battle of al-Mazraa on 2–3 August 1925, and the battles of Salkhad, al-Musayfirah and Suwayda. France sent thousands of troops from Morocco and Senegal, leading the French to regain many cities, although resistance lasted until the spring of 1927. The French sentenced Sultan al-Atrash to death, but he had escaped with the rebels to Transjordan and was eventually pardoned. He returned to Syria in 1937 after the signing of the Syrian-French Treaty.

Syria and France negotiated a treaty of independence in September 1936, and Hashim al-Atassi was the first president to be elected under the first incarnation of the modern republic of Syria. However, the treaty never came into force because the French Legislature refused to ratify it. With the fall of France in 1940 during World War II, Syria came under the control of Vichy France until the British and Free French occupied the country in the Syria-Lebanon campaign in July 1941. Continuing pressure from Syrian nationalists and the British forced the French to evacuate their troops in April 1946, leaving the country in the hands of a republican government that had been formed during the mandate.[65]

Independent Syrian Republic

Upheaval dominated Syrian politics from independence through the late 1960s. In May 1948, Syrian forces invaded Palestine, together with other Arab states, and immediately attacked Jewish settlements.[66] Their president Shukri al-Quwwatli instructed his troops in the front, “to destroy the Zionists".[67][68] The Invasion purpose was prevention of the establishment of the State of Israel.[69] Defeat in this war was one of several trigger factors for the March 1949 Syrian coup d'état by Col. Husni al-Za'im, described as the first military overthrow of the Arab World[69] since the start of the Second World War. This was soon followed by another overthrow, by Col. Sami al-Hinnawi, who was himself quickly deposed by Col. Adib Shishakli, all within the same year.[69]

Shishakli eventually abolished multipartyism altogether, but was himself overthrown in a 1954 coup and the parliamentary system was restored.[69] However, by this time, power was increasingly concentrated in the military and security establishment.[69] The weakness of Parliamentary institutions and the mismanagement of the economy led to unrest and the influence of Nasserism and other ideologies. There was fertile ground for various Arab nationalist, Syrian nationalist, and socialist movements, which represented disaffected elements of society. Notably included were religious minorities, who demanded radical reform.[69]

In November 1956, as a direct result of the Suez Crisis,[70] Syria signed a pact with the Soviet Union. This gave a foothold for Communist influence within the government in exchange for military equipment.[69] Turkey then became worried about this increase in the strength of Syrian military technology, as it seemed feasible that Syria might attempt to retake İskenderun. Only heated debates in the United Nations lessened the threat of war.[71]

On 1 February 1958, Syrian President Shukri al-Quwatli and Egypt's Nasser announced the merging of Egypt and Syria, creating the United Arab Republic, and all Syrian political parties, as well as the communists therein, ceased overt activities.[65] Meanwhile, a group of Syrian Ba'athist officers, alarmed by the party's poor position and the increasing fragility of the union, decided to form a secret Military Committee; its initial members were Lieutenant-Colonel Muhammad Umran, Major Salah Jadid and Captain Hafez al-Assad. Syria seceded from the union with Egypt on 28 September 1961, after a coup.

Ba'athist Syria

The ensuing instability, following the 1961 coup culminated in the 8 March 1963 Ba'athist coup. The takeover was engineered by members of the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party, led by Michel Aflaq and Salah al-Din al-Bitar. The new Syrian cabinet was dominated by Ba'ath members.[65][69]

On 23 February 1966, the Military Committee carried out an intra-party overthrow, imprisoned President Amin Hafiz and designated a regionalist, civilian Ba'ath government on 1 March.[69] Although Nureddin al-Atassi became the formal head of state, Salah Jadid was Syria's effective ruler from 1966 until 1970.[72] The coup led to a split within the original pan-Arab Ba'ath Party: one Iraqi-led ba'ath movement (ruled Iraq from 1968 to 2003) and one Syrian-led ba'ath movement was established.

In the first part of 1967, a low-key state of war existed between Syria and Israel. Conflict over Israeli cultivation of land in the Demilitarized Zone led to 7 April prewar aerial clashes between Israel and Syria.[73] After Israel launched a preemptive strike on Egypt to begin the Six-Day War, Syria joined the war and attacked against Israel as well. In the final days of the war, Israel turned its attention to Syria, capturing two-thirds of the Golan Heights in under 48 hours.[74] The defeat caused a split between Jadid and Assad over what steps to take next.[75]

Disagreement developed between Jadid, who controlled the party apparatus, and Assad, who controlled the military. The 1970 retreat of Syrian forces sent to aid the PLO during the "Black September" hostilities with Jordan reflected this disagreement.[76] The power struggle culminated in the November 1970 Syrian Corrective Revolution, a bloodless military overthrow that installed Hafez al-Assad as the strongman of the government.[77]

On 6 October 1973, Syria and Egypt initiated the Yom Kippur War against Israel. The Israel Defense Forces reversed the initial Syrian gains and pushed deeper into Syrian territory.[78]

In early 1976, Syria entered Lebanon, beginning the thirty-year Syrian military occupation. Over the following 15 years of civil war, Syria fought for control over Lebanon, and attempted to stop Israel from taking over in southern Lebanon, through extensive use of proxy militias. Syria then remained in Lebanon until 2005.

In the late 1970s, an Islamist uprising by the Muslim Brotherhood was aimed against the government. Islamists attacked civilians and off-duty military personnel, leading security forces to also kill civilians in retaliatory strikes. The uprising had reached its climax in the 1982 Hama massacre,[79] when some 10,000 – 40,000 people were killed by regular Syrian Army troops.

In a major shift in relations with both other Arab states and the Western world, Syria participated in the US-led Gulf War against Saddam Hussein. Syria participated in the multilateral Madrid Conference of 1991, and during the 1990s engaged in negotiations with Israel. These negotiations failed, and there have been no further direct Syrian-Israeli talks since President Hafez al-Assad's meeting with then President Bill Clinton in Geneva in March 2000.[80]

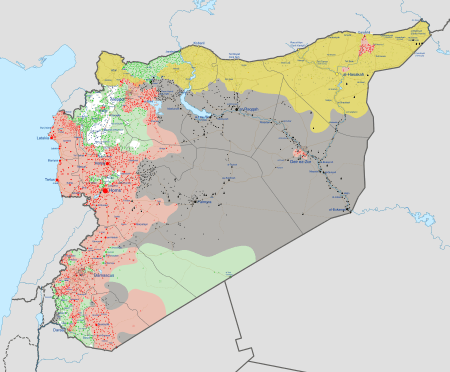

(For a more detailed map, see Cities and towns during the Syrian Civil War)

Hafez al-Assad died on 10 June 2000. His son, Bashar al-Assad, was elected President in an election in which he ran unopposed.[65] His election saw the birth of the Damascus Spring and hopes of reform, but by autumn 2001, the authorities had suppressed the movement, imprisoning some of its leading intellectuals.[81] Instead, reforms have been limited to some market reforms.[10][82][83]

On 5 October 2003, Israel bombed a site near Damascus, claiming it was a terrorist training facility for members of Islamic Jihad.[84] In March 2004, Syrian Kurds and Arabs clashed in the northeastern city of al-Qamishli. Signs of rioting were seen in the cities of Qamishli and Hasakeh.[85] In 2005, Syria ended its occupation of Lebanon.[86] On 6 September 2007, foreign jet fighters, suspected as Israeli, reportedly carried out Operation Orchard against a suspected nuclear reactor under construction by North Korean technicians.[87]

Syrian Civil War

The ongoing Syrian Civil War was inspired by the Arab Spring revolutions. It began in 2011 as a chain of peaceful protests, followed by a crackdown by the Syrian Army.[88] In July 2011, army defectors declared the formation of the Free Syrian Army and began forming fighting units. The opposition is dominated by Sunni Muslims, whereas the leading government figures are Alawites.[89] According to various sources, including the United Nations, up to 100,000 people had been killed by June 2013,[90][91][92] including 11,000 children.[93] To escape the violence, 4.9 million[94] Syrian refugees have fled to neighboring countries of Jordan,[95] Iraq,[96] Lebanon, and Turkey.[97][98] An estimated 450,000 Syrian Christians have fled their homes.[99] As the civil war has dragged on, there have been worries that the country could become fragmented and cease to function as a state.[100]

The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) reported on November 14, 2016: "the total number of victims who were killed at the hands of the Syrian regime amounts to 188,279 civilians."[101]

Geography

Syria lies between latitudes 32° and 38° N, and longitudes 35° and 43° E. It consists mostly of arid plateau, although the northwest part of the country bordering the Mediterranean is fairly green. The Northeast of the country "al-Jazira" and the South "Hawran" are important agricultural areas.[102] The Euphrates, Syria's most important river, crosses the country in the east. It is considered to be one of the fifteen states that comprise the so-called "Cradle of civilization".[103] Its land straddles the "northwest of the Arabian plate".[104]

The climate in Syria is dry and hot, and winters are mild. Because of the country's elevation, snowfall does occasionally occur during winter.[102] Petroleum in commercial quantities was first discovered in the northeast in 1956. The most important oil fields are those of Suwaydiyah, Qaratshui, Rumayian, and Tayyem, near Dayr az–Zawr. The fields are a natural extension of the Iraqi fields of Mosul and Kirkuk. Petroleum became Syria's leading natural resource and chief export after 1974. Natural gas was discovered at the field of Jbessa in 1940.[65]

Politics and government

Syria is formally a unitary republic. The constitution adopted in 2012 effectively transformed Syria into a semi-presidential republic due to the constitutional right for the election of individuals who do not form part of the National Progressive Front.[105] The President is Head of State and the Prime Minister is Head of Government.[106] The legislature, the Peoples Council, is the body responsible for passing laws, approving government appropriations and debating policy.[107] In the event of a vote of no confidence by a simple majority, the Prime Minister is required to tender the resignation of their government to the President.[108]

The executive branch consists of the president, two vice presidents, the prime minister, and the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The constitution requires the president to be a Muslim[109] but does not make Islam the state religion.

The constitution gives the president the right to appoint ministers, to declare war and state of emergency, to issue laws (which, except in the case of emergency, require ratification by the People's Council), to declare amnesty, to amend the constitution, and to appoint civil servants and military personnel.[110] According to the 2012 constitution, the president is elected by Syrian citizens in a direct election.

Syria's legislative branch is the unicameral People's Council. Under the previous constitution, Syria did not hold multi-party elections for the legislature,[110] with two-thirds of the seats automatically allocated to the ruling coalition.[111] On 7 May 2012, Syria held its first elections in which parties outside the ruling coalition could take part. Seven new political parties took part in the elections, of which Popular Front for Change and Liberation was the largest opposition party. The armed anti-government rebels, however, chose not to field candidates and called on their supporters to boycott the elections.

The President is currently the Regional Secretary of the Ba'ath party in Syria and leader of the National Progressive Front governing coalition. Outside of the coalition are 14 illegal Kurdish political parties.[112]

Syria's judicial branches include the Supreme Constitutional Court, the High Judicial Council, the Court of Cassation, and the State Security Courts. Islamic jurisprudence is a main source of legislation and Syria's judicial system has elements of Ottoman, French, and Islamic laws. Syria has three levels of courts: courts of first instance, courts of appeals, and the constitutional court, the highest tribunal. Religious courts handle questions of personal and family law.[110] The Supreme State Security Court (SSSC) was abolished by President Bashar al-Assad by legislative decree No. 53 on 21 April 2011.[113]

The Personal Status Law 59 of 1953 (amended by Law 34 of 1975) is essentially a codified sharia.[114] Article 3(2) of the 1973 constitution declares Islamic jurisprudence a main source of legislation. The Code of Personal Status is applied to Muslims by sharia courts.[115]

As a result of the ongoing civil war, various alternative governments were formed, including the Syrian Interim Government, the Democratic Union Party and localised regions governed by sharia law. Representatives of the Syrian Interim government were invited to take up Syria's seat at the Arab League on 28 March 2013 and[116] was recognised as the "sole representative of the Syrian people" by several nations including the United States, United Kingdom and France.[117][118][119]

Parliamentary elections were held on 13 April 2016 in the government-controlled areas of Syria, for all 250 seats of Syria's unicameral legislature, the Majlis al-Sha'ab, or the People's Council of Syria.[120] Even before results had been announced, several nations, including Germany, the United States and the United Kingdom, have declared their refusal to accept the results, largely citing it "not representing the will of the Syrian people.[121] However, representatives of the Russian Federation have voiced their support of this election's results. Syria's system of government is considered to be non-democratic by the North American NGO Freedom House.[122]

Human rights

The situation for human rights in Syria has long been a significant concern among independent organizations such as Human Rights Watch, who in 2010 referred to the country's record as "among the worst in the world."[123] The US State Department funded Freedom House[124] ranked Syria "Not Free" in its annual Freedom in the World survey.[125]

The authorities are accused of arresting democracy and human rights activists, censoring websites, detaining bloggers, and imposing travel bans. Arbitrary detention, torture, and disappearances are widespread.[126] Although Syria's constitution guarantees gender equality, critics say that personal statutes laws and the penal code discriminate against women and girls. Moreover, it also grants leniency for so-called 'Honour killing'.[126] As of 9 November 2011 during the uprising against President Bashar al-Assad, the United Nations reported that of the over 3500 total deaths, over 250 deaths were children as young as 2 years old, and that boys as young as 11 years old have been gang raped by security services officers.[127][128] People opposing President Assad's rule claim that more than 200, mostly civilians, were massacred and about 300 injured in Hama in shelling by the Government forces on 12 July 2012.[129]

In August 2013 the government was suspected of using chemical weapons against its civilians. US Secretary of State John Kerry said it was "undeniable" that chemical weapons had been used in the country and that President Bashar al-Assad's forces had committed a "moral obscenity" against his own people. "Make no mistake," Kerry said. "President Obama believes there must be accountability for those who would use the world's most heinous weapon against the world's most vulnerable people. Nothing today is more serious, and nothing is receiving more serious scrutiny".[130]

The Emergency Law, effectively suspending most constitutional protections, was in effect from 1963 until 21 April 2011.[113] It was justified by the government in the light of the continuing war with Israel over the Golan Heights.

In August 2014, UN Human Rights chief Navi Pillay criticized the international community over its "paralysis" in dealing with the more than 3-year-old civil war gripping the country, which by 30 April 2014, had resulted in 191,369 deaths with war crimes, according to Pillay, being committed with total impunity on all sides in the conflict. Minority Alawites and Christians are being increasingly targeted by Islamists and other groups fighting in the Syrian civil war.[131][132]

Military

The President of Syria is commander in chief of the Syrian armed forces, comprising some 400,000 troops upon mobilization. The military is a conscripted force; males serve in the military upon reaching the age of 18.[133] The obligatory military service period is being decreased over time, in 2005 from two and a half years to two years, in 2008 to 21 months and in 2011 to year and a half.[134] About 20,000 Syrian soldiers were deployed in Lebanon until 27 April 2005, when the last of Syria's troops left the country after three decades.[133]

The breakup of the Soviet Union—long the principal source of training, material, and credit for the Syrian forces—may have slowed Syria's ability to acquire modern military equipment. It has an arsenal of surface-to-surface missiles. In the early 1990s, Scud-C missiles with a 500-kilometre (310-mile) range were procured from North Korea, and Scud-D, with a range of up to 700 kilometres (430 miles), is allegedly being developed by Syria with the help of North Korea and Iran, according to Zisser.[135]

Syria received significant financial aid from Arab states of the Persian Gulf as a result of its participation in the Persian Gulf War, with a sizable portion of these funds earmarked for military spending.

Foreign relations

Ensuring national security, increasing influence among its Arab neighbors, and securing the return of the Golan Heights, have been the primary goals of Syria's foreign policy. At many points in its history, Syria has seen virulent tension with its geographically cultural neighbors, such as Turkey, Israel, Iraq, and Lebanon. Syria enjoyed an improvement in relations with several of the states in its region in the 21st century, prior to the Arab Spring and the Syrian Civil War.

Since the ongoing civil war of 2011, and associated killings and human rights abuses, Syria has been increasingly isolated from the countries in the region, and the wider international community. Diplomatic relations have been severed with several countries including: Britain, Canada, France, Italy, Germany, Tunisia, Egypt, Libya, the United States, Belgium, Spain, and the Arab states of the Persian Gulf.[136]

From the Arab league, Syria continues to maintain diplomatic relations with Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Sudan and Yemen. Syria's violence against civilians has also seen it suspended from the Arab League and the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in 2012. Syria continues to foster good relations with its traditional allies, Iran and Russia, who are among the few countries which have supported the Syrian government in its conflict with the Syrian opposition.

Syria is included in the European Union's European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) which aims at bringing the EU and its neighbours closer.

International disputes

In 1939, while Syria was still a French mandate the French ceded the Sanjak of Alexandretta to Turkey as part of a treaty of friendship in World War II. In order to facilitate this, a faulty election was done in which ethnic Turks who were originally from the Sanjak but lived in Adana and other areas near the border in Turkey came to vote in the elections, shifting the election in favor of secession. Through this, the Hatay Province of Turkey was formed. The move by the French was very controversial in Syria, and only 5 years later Syria became independent.[137]

Israel unilaterally annexed the Golan Heights in 1981, although the Syrian government continues to demand the return of this territory.

The Syrian occupation of Lebanon began in 1976 as a result of the civil war and ended in April 2006 in response to domestic and international pressure after the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri.

Administrative divisions

Syria is divided into 14 governorates, which are sub-divided into 61 districts, which are further divided into sub-districts.

| No. | Governorate | Capital | |

|---|---|---|---|

Governorates of Syria | |||

| 1 | Latakia | Latakia | |

| 2 | Idlib | Idlib | |

| 3 | Aleppo | Aleppo | |

| 4 | Al-Raqqah | Al-Raqqah | |

| 5 | Al-Hasakah | Al-Hasakah | |

| 6 | Tartus | Tartus | |

| 7 | Hama | Hama | |

| 8 | Deir ez-Zor | Deir ez-Zor | |

| 9 | Homs | Homs | |

| 10 | Damascus | – | |

| 11 | Rif Dimashq | – | |

| 12 | Quneitra | Quneitra | |

| 13 | Daraa | Daraa | |

| 14 | Al-Suwayda | Al-Suwayda |

Agrarian Reform

Agrarian reform measures were introduced into Syria which consisted of three interrelated programs: Legislation regulation the relationship between agriculture laborers and landowners: legislation governing the ownership and use of private and state domain land and directing the economic organization of peasants; and measures reorganizing agricultural production under state control.[138] Despite high levels of inequality in land ownership these reforms allowed for progress in redistribution of land from 1958 to 1961 than any other reforms in Syria's history, since independence.

The first law passed (Law 134; passed September 4, 1958) in response to concern about peasant mobilization and expanding peasants' rights.[139] This was designed to strengthen the position of sharecroppers and agricultural laborers in relation to land owners.[139] This law lead to the creation of the Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs, which announced the implementation of new laws that would allow the regulation of working condition especially for women and adolescents, set hours of work, and introduce the principle of minimum wage for paid laborers and an equitable division of harvest for sharecroppers.[140] Furthermore, it obligated landlords to honor both written and oral contracts, established collective barging, contained provisions for workers' compensation, health, housing, and employment services.[139] Law 134 was not designed strictly to protect workers. It also acknowledged the rights of landlords to form their own syndicates.[139]

Internet and telecommunications

The Telecommunications in Syria are overseen by the Ministry of Communications and Technology.[141] In addition, Syrian Telecom plays an integral role in the distribution of government internet access.[142] The Syrian Electronic Army serves as a pro-government military faction in cyberspace and has been long considered an enemy of the hacktivist group Anonymous.[143] Because of internet censorship laws, 13,000 internet activists have been arrested between March 2011 and August 2012.[144]

Economy

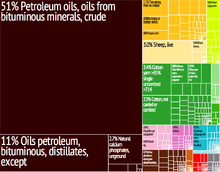

As of 2015, the Syrian economy relies upon inherently unreliable revenue sources such as dwindling customs and income taxes which are heavily bolstered by lines of credit from Iran.[145] Iran is believed to spend between $6 billion and $20 billion USD a year on Syria during the Syrian Civil War.[146] The Syrian economy has contracted 60% and the Syrian pound has lost 80% of its value, with the economy becoming part state-owned and part war economy.[147] At the outset of the ongoing Syrian Civil War, Syria was classified by the World Bank as a "lower middle income country."[148] In 2010, Syria remained dependent on the oil and agriculture sectors.[149] The oil sector provided about 40% of export earnings.[149] Proven offshore expeditions have indicated that large sums of oil exist on the Mediterranean Sea floor between Syria and Cyprus.[150] The agriculture sector contributes to about 20% of GDP and 20% of employment. Oil reserves are expected to decrease in the coming years and Syria has already become a net oil importer.[149] Since the civil war began, the economy shrank by 35%, and the Syrian pound has fallen to one-sixth of its prewar value.[151] The government increasingly relies on credit from Iran, Russia and China.[151]

The economy is highly regulated by the government, which has increased subsidies and tightened trade controls to assuage protesters and protect foreign currency reserves.[152] Long-run economic constraints include foreign trade barriers, declining oil production, high unemployment, rising budget deficits, and increasing pressure on water supplies caused by heavy use in agriculture, rapid population growth, industrial expansion, and water pollution.[152] The UNDP announced in 2005 that 30% of the Syrian population lives in poverty and 11.4% live below the subsistence level.[65]

Syria's share in global exports has eroded gradually since 2001.[153] The real per capita GDP growth was just 2.5% per year in the 2000–2008 period.[153] Unemployment is high at above 10%. Poverty rates have increased from 11% in 2004 to 12.3% in 2007.[153] In 2007, Syria's main exports include crude oil, refined products, raw cotton, clothing, fruits, and grains. The bulk of Syrian imports are raw materials essential for industry, vehicles, agricultural equipment, and heavy machinery. Earnings from oil exports as well as remittances from Syrian workers are the government's most important sources of foreign exchange.[65]

Political instability poses a significant threat to future economic development.[154] Foreign investment is constrained by violence, government restrictions, economic sanctions, and international isolation. Syria's economy also remains hobbled by state bureaucracy, falling oil production, rising budget deficits, and inflation.[154]

Prior to the civil war in 2011, the government hoped to attract new investment in the tourism, natural gas, and service sectors to diversify its economy and reduce its dependence on oil and agriculture. The government began to institute economic reforms aimed at liberalizing most markets, but those reforms were slow and ad hoc, and have been completely reversed since the outbreak of conflict in 2011.[155]

As of 2012, because of the ongoing Syrian civil war, the value of Syria's overall exports has been slashed by two-thirds, from the figure of US$12 billion in 2010 to only US$4 billion in 2012.[156] Syria's GDP declined by over 3% in 2011,[157] and is expected to further decline by 20% in 2012.[158]

As of 2012, Syria's oil and tourism industries in particular have been devastated, with US$5 billion lost to the ongoing conflict of the civil war.[156] Reconstruction needed because of the ongoing civil war will cost as much as US$10 billion.[156] Sanctions have sapped the government's finance. US and European Union bans on oil imports, which went into effect in 2012, are estimated to cost Syria about $400 million a month.[159]

Revenues from tourism have dropped dramatically, with hotel occupancy rates falling from 90% before the war to less than 15% in May 2012.[160] Around 40% of all employees in the tourism sector have lost their jobs since the beginning of the war.[160]

In May 2015, ISIS captured Syria's phosphate mines, one of the Assad regime's last chief sources of income.[161] The following month, ISIS blew up a gas pipeline to Damascus that was used to generate heating and electricity in Damascus and Homs; "the name of its game for now is denial of key resources to the regime" an analyst stated.[162] In addition, ISIS is closing in on Shaer gas field and three other facilities in the area—Hayan, Jihar and Ebla—with the loss of these western gas fields having the potential to cause Iran to further subsidize the Assad regime.[163]

Petroleum industry

Syria's petroleum industry has been subject to sharp decline. In September 2014, ISIS was producing more oil than the regime at 80,000 bbl/d (13,000 m3/d) compared to the regime's 17,000 bbl/d (2,700 m3/d) with the Syrian Oil Ministry stating that by the end of 2014, oil production had plunged further to 9,329 bbl/d (1,483.2 m3/d); ISIS has since captured a further oil field, leading to a projected oil production of 6,829 bbl/d (1,085.7 m3/d).[145] In the third year of the Syrian Civil War, the deputy economy minister Salman Hayan stated that Syria's two main oil refineries were operating at less than 10% capacity.[164]

Historically, the country produced heavy-grade oil from fields located in the northeast since the late 1960s. In the early 1980s, light-grade, low-sulphur oil was discovered near Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria. Syria's rate of oil production has decreased dramatically from a peak close to 600,000 barrels per day (95,000 m3/d) (bpd) in 1995 down to less than 182,500 bbl/d (29,020 m3/d) in 2012.[165] Since 2012 the production has decreased even more, reaching in 2014 32,000 barrels per day (5,100 m3/d) (bpd). Official figures quantity the production in 2015 at 27,000 barrels per day (4,300 m3/d), but those figures have to be taken with precaution because it is difficult to estimate the oil that is currently produced in the rebel held areas.

Prior to the uprising, more than 90% of Syrian oil exports were to EU countries, with the remainder going to Turkey.[160] Oil and gas revenues constituted in 2012 around 20% of total GDP and 25% of total government revenue.[160]

Transport

Syria has four international airports (Damascus, Aleppo, Lattakia and Kamishly), which serve as hubs for Syrian Air and are also served by a variety of foreign carriers.

The majority of Syrian cargo is carried by Chemins de Fer Syriens (the Syrian railway company), which links up with Turkish State Railways (the Turkish counterpart). For a relatively underdeveloped country, Syria's railway infrastructure is well maintained with many express services and modern trains.[166]

The road network in Syria is 69,873 kilometres (43,417 miles) long, including 1,103 kilometres (685 miles) of expressways. The country also has 900 kilometres (560 miles) of navigable but not economically significant waterways.[167]

Water supply and sanitation

Syria is a semiarid country with scarce water resources. The largest water consuming sector in Syria is agriculture. Domestic water use stands at only about 9% of total water use.[168] A big challenge for Syria is its high population growth with a rapidly increasing demand for urban and industrial water. In 2006 the population of Syria was 19.4 million with a growth rate of 2.7%.[169]

Demographics

| Historical populations (in thousands) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1960 | 4,565,000 | — |

| 1970 | 6,305,000 | +3.28% |

| 1981 | 9,046,000 | +3.34% |

| 1994 | 13,782,000 | +3.29% |

| 2004 | 17,921,000 | +2.66% |

| 2014 | 17,952,000 | +0.02% |

| Source: Central Bureau of Statistics of the Syrian Arab Republic, 2011[170] | ||

Most people live in the Euphrates River valley and along the coastal plain, a fertile strip between the coastal mountains and the desert. Overall population density in Syria is about 99 per square kilometre (258 per square mile). According to the World Refugee Survey 2008, published by the U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, Syria hosted a population of refugees and asylum seekers numbering approximately 1,852,300. The vast majority of this population was from Iraq (1,300,000), but sizeable populations from Palestine (543,400) and Somalia (5,200) also lived in the country.[171]

In what the UN has described as "the biggest humanitarian emergency of our era",[172] about 9.5 million Syrians, half the population, have been displaced since the outbreak of the Syrian Civil War in March 2011;[173] 4 million are outside the country as refugees.[174]

Ethnic groups

.jpg)

.jpg)

Syrians are an overall indigenous Levantine people, closely related to their immediate neighbours, like Lebanese people, Palestinians, Iraqis, Maltese and Jordanians.[175][176] Syria has a population of approximately 17,065,000 (2014 est.)[3] Syrian Arabs, together with some 600,000 Palestinian Arabs, make up roughly 74% of the population (if Syriac Christians are excluded).[152]

The indigenous Christian Western Aramaic-speakers and Assyrians are numbered around 400,000 people,[177] with the Western Aramaic-speakers living all over the country, particularly in major urban centers, while the Assyrians mainly reside in the north and northeast (Homs, Aleppo, Qamishli, Hasakah). Many (particularly the Assyrian group) still retain several Neo-Aramaic dialects as spoken and written languages, while villagers of Ma'loula, Jubb'adin and Bakh'a still retain Western Aramaic.[178]

The second largest ethnic group in Syria are the Kurds. They constitute about 9%[179] to 10%[180] of the population, or approximately 1.6 million people (including 40,000 Yazidis[180]). Most Kurds reside in the northeastern corner of Syria and most speak the Kurmanji variant of the Kurdish language.[179]

The third largest ethnic group are the Turkish-speaking Syrian Turkmen, with estimates suggesting they constitute approximately 4-5% of the population of Syria.[180] However, their population is significantly higher if Arabized Turkmen were also taken into account.[180] There are no reliable estimates of their total population, with estimates ranging from several hundred thousand to 3.5 million.[181][182][183]

The fourth largest ethnic group are the Assyrians (3-4%),[180] followed by the Circassians (1.5%)[180] and the Armenians (1%),[180] most of which are the descendants of refugees who arrived in Syria during the Armenian Genocide. Syria holds the 7th largest Armenian population in the world. They are mainly gathered in Aleppo, Qamishli, Damascus and Kesab.

There are also smaller ethnic minority groups, such as the Albanians, Bosnians, Georgians, Greeks, Persians, Pashtuns and Russians.[180] However, most of these ethnic minorities have become Arabized to some degree, particularly those who practice the Muslim faith.[180]

Syria was once home to a substantial population of Jews, with large communities in Damascus, Aleppo, and Qamishii. Due to a combination of persecution in Syria and opportunities elsewhere, the Jews began to emigrate in the second half of the 19th century to Great Britain, the United States, and Israel. The process was completed with the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. Today only a few Jews remain in Syria.

The largest concentration of the Syrian diaspora outside the Arab world is in Brazil, which has millions of people of Arab and other Near Eastern ancestries.[184] Brazil is the first country in the Americas to offer humanitarian visas to Syrian refugees.[185] The majority of Arab Argentines are from either Lebanese or Syrian background.[186]

Religion

Sunni Muslims make up about 74% of Syria's population[187] and Sunni Arabs account for 59–60% of the population, most Kurds (8.5%)[188] and most Turkoman (3%)[188] are also Sunni, while 13% of Syrians are Shia Muslims (particularly Alawite, Twelvers, and Ismailis but also Arabs, Kurds and Turkoman), 10% Christian[187] (the majority Antiochian Orthodox, the rest including Greek Catholic, Assyrian Church of the East, Armenian Orthodox, Protestants and other denominations), and 3% Druze.[187] Druze number around 500,000, and concentrate mainly in the southern area of Jabal al-Druze.[189]

President Bashar al-Assad's family is Alawite and Alawites dominate the government of Syria and hold key military positions.[190] In May 2013, SOHR stated that out of 94,000 killed during the Syrian Civil War, at least 41,000 were Alawites.[191]

Christians (2.5 million), a sizable number of whom are found among Syria's population of Palestinian refugees, are divided into several groups. Chalcedonian Antiochian Orthodox make up 45.7% of the Christian population; the Catholics (Melkite, Armenian Catholic, Syriac Catholic, Maronite, Chaldean Catholic and Latin) make up 16.2%; the Armenian Apostolic Church 10.9%, the Syriac Orthodox make up 22.4%; Assyrian Church of the East and several smaller Christian denominations account for the remainder. Many Christian monasteries also exist. Many Christian Syrians belong to a high socio-economic class.[192]

Languages

Arabic is the official language. Several modern Arabic dialects are used in everyday life, most notably Levantine in the west and Mesopotamian in the northeast. Kurdish (in its Kurmanji form) is widely spoken in the Kurdish regions of Syria. Armenian and Turkish (South Azeri dialect) are spoken among the Armenian and Turkmen minorities.

Aramaic was the lingua franca of the region before the advent of Arabic, and is still spoken among Assyrians, and Classical Syriac is still used as the liturgical language of various Syriac Christian denominations. Most remarkably, Western Neo-Aramaic is still spoken in the village of Ma'loula as well as two neighboring villages, 56 km (35 mi) northeast of Damascus.

English and French are widely spoken as a second language, but English is more often used.

Largest cities

| | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | Province | Pop. | ||||||

Aleppo Damascus |

1 | Aleppo | Aleppo Governorate | 2,132,100 |  Homs | ||||

| 2 | Damascus | Damascus | 1,711,000 | ||||||

| 3 | Homs | Homs Governorate | 652,609 | ||||||

| 4 | Latakia | Latakia Governorate | 383,786 | ||||||

| 5 | Hama | Hama Governorate | 312,994 | ||||||

| 6 | Ar-Raqqah | Ar Raqqah Governorate | 220,488 | ||||||

| 7 | Deir ez-Zor | Deir ez-Zor Governorate | 211,857 | ||||||

| 8 | Al-Hasakah | Al-Hasakah Governorate | 188,160 | ||||||

| 9 | Qamishli | Al-Hasakah Governorate | 184,231 | ||||||

| 10 | Sayyidah Zaynab | Rif Dimashq Governorate | 136,427 | ||||||

Culture

Syria is a traditional society with a long cultural history.[193] Importance is placed on family, religion, education, self-discipline and respect. Syrians' taste for the traditional arts is expressed in dances such as the al-Samah, the Dabkeh in all their variations, and the sword dance. Marriage ceremonies and the births of children are occasions for the lively demonstration of folk customs.[194]

Arts

The literature of Syria has contributed to Arabic literature and has a proud tradition of oral and written poetry. Syrian writers, many of whom migrated to Egypt, played a crucial role in the nahda or Arab literary and cultural revival of the 19th century. Prominent contemporary Syrian writers include, among others, Adonis, Muhammad Maghout, Haidar Haidar, Ghada al-Samman, Nizar Qabbani and Zakariyya Tamer.

Ba'ath Party rule, since the 1966 coup, has brought about renewed censorship. In this context, the genre of the historical novel, spearheaded by Nabil Sulayman, Fawwaz Haddad, Khyri al-Dhahabi and Nihad Siris, is sometimes used as a means of expressing dissent, critiquing the present through a depiction of the past. Syrian folk narrative, as a subgenre of historical fiction, is imbued with magical realism, and is also used as a means of veiled criticism of the present. Salim Barakat, a Syrian émigré living in Sweden, is one of the leading figures of the genre. Contemporary Syrian literature also encompasses science fiction and futuristic utopiae (Nuhad Sharif, Talib Umran), which may also serve as media of dissent.

Popular culture

The Syrian music scene, in particular that of Damascus, has long been among the Arab world's most important, especially in the field of classical Arab music. Syria has produced several pan-Arab stars, including Asmahan, Farid al-Atrash and singer Lena Chamamyan. The city of Aleppo is known for its muwashshah, a form of Andalous sung poetry popularized by Sabri Moudallal, as well as for popular stars like Sabah Fakhri.

Television was first introduced to Syria in 1960, when Syria and Egypt (which adopted television that same year) were part of the United Arab Republic. It broadcast in black and white until 1976. Syrian soap operas have considerable market penetration throughout the eastern Arab world.[195]

Nearly all of Syria's media outlets are state-owned, and the Ba'ath Party controls nearly all newspapers.[196] The authorities operate several intelligence agencies,[197] among them Shu'bat al-Mukhabarat al-'Askariyya, employing a large number of operatives.[198] Since the Syrian Civil War many of Syria's artists, poets, writers and activists have remained incarcerated, including famed cartoonist Akram Raslam.[199]

Sports

The most popular sports in Syria are football, basketball, swimming, and tennis. Damascus was home to the fifth and seventh Pan Arab Games. Many popular football teams are based in Damascus, Aleppo, Homs, Latakia, etc.

The Abbasiyyin Stadium in Damascus is home to the Syrian national football team. The team enjoyed some success, having qualified for four Asian Cup competitions. The team had its first international on 20 November 1949, losing to Turkey 7–0. The team was ranked 101st in the world by FIFA as of June 2016.

Cuisine

Linked to the regions of Syria where a specific dish has originated, Syrian cuisine is rich and varied in its ingredients. Syrian food mostly consists of Southern Mediterranean, Greek, and Southwest Asian dishes. Some Syrian dishes also evolved from Turkish and French cooking: dishes like shish kebab, stuffed zucchini/courgette, yabra' (stuffed grape leaves, the word yapra' derıves from the Turkish word 'yaprak' meaning leaf).

The main dishes that form Syrian cuisine are kibbeh, hummus, tabbouleh, fattoush, labneh, shawarma, mujaddara, shanklish, pastırma, sujuk and baklava. Baklava is made of filo pastry filled with chopped nuts and soaked in honey. Syrians often serve selections of appetizers, known as meze, before the main course. Za'atar, minced beef, and cheese manakish are popular hors d'œuvres. The Arabic flatbread khubz is always eaten together with meze.

Drinks in Syria vary, depending on the time of day and the occasion. Arabic coffee, also known as Turkish coffee, is the most well-known hot drink, usually prepared in the morning at breakfast or in the evening. It is usually served for guests or after food. Arak, an alcoholic drink, is also a well-known beverage served mostly on special occasions. More examples of Syrian beverages include Ayran, Jallab, White coffee, and a locally manufactured beer called Al Shark.[200]

Education

Education is free and compulsory from ages 6 to 12. Schooling consists of 6 years of primary education followed by a 3-year general or vocational training period and a 3-year academic or vocational program. The second 3-year period of academic training is required for university admission. Total enrollment at post-secondary schools is over 150,000. The literacy rate of Syrians aged 15 and older is 90.7% for males and 82.2% for females.[201][202]

Since 1967, all schools, colleges, and universities have been under close government supervision by the Ba'ath Party.[203]

There are 6 state universities in Syria[204] and 15 private universities.[205] The top two state universities are University of Damascus (180,000 students)[206] and University of Aleppo.[207] The top private universities in Syria are: Syrian Private University, Arab International University, University of Kalamoon and International University for Science and Technology. There are also many higher institutes in Syria, like the Higher Institute of Business Administration, which offer undergraduate and graduate programs in business.[208]

According to the Webometrics Ranking of World Universities, the top-ranking universities in the country are Damascus University (3540th worldwide), the University of Aleppo (7176th) and Tishreen University (7968th).[209]

Health

In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 3.4% of the country's GDP. In 2008, there were 14.9 physicians and 18.5 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[210] The life expectancy at birth was 75.7 years in 2010, or 74.2 years for males and 77.3 years for females.[211]

See also

- Index of Syria-related articles

- Outline of Syria

- Syrian Civil War

- Refugees of the Syrian Civil War

- International recognition of the Syrian National Council

- Federation of Northern Syria – Rojava

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ "Constitution of Syria 2012". Scribd. 15 February 2012. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Syrian ministry of foreign affairs".

- 1 2 "The World Factbook". CIA. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 "Syria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ↑ "World Bank GINI index". World Bank. Retrieved 22 January 2013.

- ↑ "2015 Human Development Report" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2015. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ Gammer 2004, p. 64.

- ↑ Who cares for the Mandaeans?, Australian Islamist Monitor.

- ↑ "Neolithic Tell Ramad in the Damascus Basin of Syria". Archive. Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- 1 2 Michael Bröning (7 March 2011). "The Sturdy House That Assad Built". The Foreign Affairs.

- ↑ MacFarquhar, Neil (12 November 2011). "Arab League Votes to Suspend Syria". The New York Times. Retrieved 12 November 2011.

- ↑ "Regional group votes to suspend Syria; rebels claim downing of jet". CNN. 14 August 2012. Retrieved 14 August 2012.

- ↑ "Syria suspends its membership in Mediterranean union". Xinhua News Agency. 1 December 2012.

- ↑ Sherwell, Phillip. "Syria replaces Afghanistan as world's least peaceful country". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 22 September 2014.

- ↑ Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- ↑ Frye, R. N. (1992). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 51 (4): 281–285. doi:10.1086/373570.

- ↑ Herodotus, The Histories, VII.63, s:History of Herodotus/Book 7.

- ↑ Joseph, John (2008). "Assyria and Syria: Synonyms?" (PDF).

- ↑ First proposed by Theodor Nöldeke in 1881; cf. Harper, Douglas (November 2001). "Syria". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 13 June 2007.

- ↑ Pipes, Daniel (1992). Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Middle East Forum. p. 13. ISBN 0-19-506022-9. Retrieved 1 February 2010.

- ↑ Pliny. "Book 5 Section 66". Natural History. 77AD. University of Chicago. ISBN 84-249-1901-7.

- ↑ "Syria :: Roman provincial organization". Britannica Online Encyclopedia. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- ↑ "jabbul head louvre". Louvre.fr. Retrieved 24 July 2014.

- ↑ Pettinato, Giovanni. The Archives of Ebla; Gelb, I. J. "Thoughts about Ibla: A Preliminary Evaluation" in Monographic Journals of the Near East, Syro-Mesopotamian Studies 1/1 (May 1977) pp. 3–30.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. p. 239.

- ↑ Ian Shaw; Robert Jameson. A Dictionary of Archaeology. p. 211.

- ↑ Ross Burns. Monuments of Syria: A Guide. p. 155.

- ↑ Paolo Matthiae; Nicoló Marchetti. Ebla and its Landscape: Early State Formation in the Ancient Near East. p. 35.

- ↑ Victor Harold Matthews, Don C. Benjamin. Old Testament Parallels: Laws and Stories from the Ancient Near East. p. 241.

- 1 2 "Syria: A country Study – Ancient Syria". Library of Congress. Data as of April 1987. Retrieved 5 September 2007. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Kenneth Anderson Kitchen. On the Reliability of the Old Testament. p. 285.

- ↑ Stephen C. Neff. Justice Among Nations. p. 14.

- ↑ "The Aramaic Language and Its Classification" (PDF). Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1).

- ↑ Trevor Bryce. Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. p. 16.

- ↑ Cyrus Herzl Gordon; Gary Rendsburg; Nathan H. Winter. Eblaitica: Essays on the Ebla Archives and Eblaite Language, Volume 4. p. 68.

- ↑ John F. Healey. The Early Alphabet. p. 22.

- 1 2 Stephanie Dalley. Mari and Karana: Two Old Babylonian Cities. p. 44.

- ↑ Nadav Naʼaman. Canaan in the Second Millennium B.C.E. p. 285.

- ↑ Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen Edwards. The Cambridge Ancient History. p. 32.

- ↑ William J. Hamblin. Warfare in the Ancient Near East to 1600 BC. p. 259.

- ↑ Jack M. Sasson. The Military Establishments at Mari. p. 2+3.

- ↑ Relations between God and Man in the Hurro-Hittite Song of Release, Mary R. Bachvarova, Journal of the American Oriental Society, Jan–Mar SAAD 2005

- ↑ John Lange. The Philosophy of Historiography. p. 475.

- ↑ Immanuel Velikovsky. Ramses II and His Time. p. 23.

- ↑ Douglas Frayne. Ugarit in Retrospect. p. 23,24,25.

- ↑ Georges Roux, Ancient Iraq, 3rd ed., Penguin Books, London, 1991, p.381

- ↑ Rollinger, Robert (2006). "The terms "Assyria" and "Syria" again" (PDF)". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. 65 (4): 284–287. doi:10.1086/511103.

- ↑ Hist." xviii., vii. 1

- ↑ Charlotte Higgins. "When Syrians, Algerians and Iraqis patrolled Hadrian's Wall". the Guardian.

- 1 2 Cavendish Corporation, Marshall (2006). World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish. p. 183. ISBN 0-7614-7571-0.

- 1 2 Muir, William (1861), The life of Mahomet, Smith, Elder & Co, pp. 225–226

- ↑ Mubarakpuri, The Sealed Nectar, pp. 193-194. (online)

- ↑ Watt, W. Montgomery (1956). Muhammad at Medina. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-19-577307-1.

This expedition receives scant notice in the sources, but in some ways it is the most significant so far. As Dumah was some 800 km (500 mi) from Medina there can have been no immediate threat to Muhammad, but it may be, as Caetani suggests, 1 that communications with Syria were being interrupted and supplies to Medina stopped. It is tempting to suppose that was already envisaging something of the expansion which took place after his death.

(free online) - ↑ "Syria: History". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ Farhad Daftary. A Short History of the Ismailis. 1998, Edinburg, UK. Edinburg University Press. Page 146.

- ↑ Timeframe pp. 59–75.

- ↑ "Battle of Aleppo". Everything2.com. 22 February 2003. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "The Eastern Mediterranean, 1400–1600 A.D". Metmuseum.org. Archived from the original on 28 April 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2011.

- 1 2 "Syria – Ottoman". Library of Congress Country Studies. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ a b Stanford J. Shaw, "Dynamics of Ottoman Society and administration", in "History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey"

- ↑ Pouring a People into the Desert:The "Definitive Solution" of the Unionists to the Armenian Question, Fuat Dundar, A Question of Genocide, ed. Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Muge Gocek and Norman M. Naimark, (Oxford University Press, 2011), 280–281.

- ↑ "Mandat Syrie-Liban" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 June 2008. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ James Barr (2011). a line in the sand. Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-84737-453-0.

- ↑ Peter N. Stearns; William Leonard Langer (2001). "The Middle East, p. 761". The Encyclopedia of World History. Houghton Mifflin Books. ISBN 978-0-395-65237-4.