Zenobia

| Zenobia | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Queen of Palmyra Empress | |||||

Zenobia as Augusta (empress) on the obverse of an Antoninianus | |||||

| Empress | |||||

| Tenure | 272 | ||||

| Predecessor | title created | ||||

| Successor | none | ||||

| Queen mother of Palmyra | |||||

| Tenure | 267–272 | ||||

| Predecessor | title created | ||||

| Successor | none | ||||

| Queen consort of Palmyra | |||||

| Tenure | 260–267 | ||||

| Predecessor | title created | ||||

| Successor | none | ||||

| Born |

c. 240 Palmyra, Syria | ||||

| Died | after 274 | ||||

| Spouse | Odaenathus | ||||

| Issue |

Vaballathus Hairan II | ||||

| |||||

Septimia Zenobia (Palmyrene: ![]() (Btzby), spelled Bat-Zabbai; c.240-c.272), was a third-century queen of the Palmyrene Empire centered in Palmyra, Syria. Many legends surround her ancestry; she was certainly born to a noble Palmyrene family and she married the ruler of the city, Odaenathus. Her husband later became king in 260 and lifted the city into the supreme power of the Near East by defeating the Sassanians and stabilizing the Roman East. Following his assassination, she became the regent for her son Vaballathus, but held de facto power throughout his reign while he was kept in the shadow.

(Btzby), spelled Bat-Zabbai; c.240-c.272), was a third-century queen of the Palmyrene Empire centered in Palmyra, Syria. Many legends surround her ancestry; she was certainly born to a noble Palmyrene family and she married the ruler of the city, Odaenathus. Her husband later became king in 260 and lifted the city into the supreme power of the Near East by defeating the Sassanians and stabilizing the Roman East. Following his assassination, she became the regent for her son Vaballathus, but held de facto power throughout his reign while he was kept in the shadow.

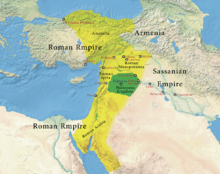

In 270, Zenobia launched an invasion that brought most of the Roman East under her sway, culminating with the annexation of Egypt into the new empire. The queen remained nominally subordinate to Rome even as her armies conquered most of the Roman Empire's eastern provinces. By mid-271, Zenobia's realm extended from Ankara in the north to southern Egypt. However, in 272, faced with Roman emperor Aurelian's campaign, Zenobia declared her son emperor and assumed the title of empress herself, thus declaring Palmyra's official secession from Rome. The Romans were victorious and after heavy fighting, the queen was besieged in her capital and captured by Aurelian, who carried her to Rome where she spent the rest of her life.

Zenobia was a cultured monarch; she opened her court for scholars and philosophers, creating an intellectual environment. She protected the religious minorities and showed tolerance toward her subjects. The queen maintained a stable administration and successfully presided over a multicultural, multi-ethnic empire. Zenobia died after 274 and many tales are told about her fate. Her tragic story became a legend and an inspiration to many historians, artists and novelists. Zenobia is an icon in Syria where she is considered a national hero.

Name and appearance

| “ | Her face was dark and of a swarthy hue, her eyes were black and powerful beyond the usual wont, her spirit divinely great, and her beauty incredible. So white were her teeth that many thought that she had pearls in place of teeth. | ” |

| — The Augustan History.[1] | ||

The queen was born c. 240–241;[2] she bore the gentilicium (surname) Septimia,[3] and her native Palmyrene name was Bat-Zabbai (written in Palmyrene alphabet as Btzby),[4] an Aramaic name that means the "daughter of Zabbai".[5] In Greek (Palmyra's diplomatic and second language used in many Palmyrene inscriptions), she used the name Zenobia, a name that means "one whose life derives from Zeus".[6] Ninth-century historian al-Tabari, in his highly fictionalized account,[7] said that the queen's name was Na'ila al-Zabba'.[8] The Manichaean sources name the queen "Tadi".[9]

In Palmyra, names such as Zabeida, Zabdila, Zabbai or Zabda were often transformed into "Zenobios" (masculine) and "Zenobia" (feminine) when written in Greek.[10] Historian Victor Duruy believed that the queen used the Greek name as a translation to her native name to gratify her Greek subjects.[11] No contemporary sculptural works depicting Zenobia were ever found in Palmyra or elsewhere, and only the inscriptions on statues' bases indicate that there once stood a statue of the queen; most of the known representations of Zenobia come from her coins.[12] British scholar William Wright visited Palmyra toward the end of the nineteenth century in hope of finding any sculpture that represents the queen, but his quest was in vain.[13]

Sources: aside from archaeological evidence, the events and life of Zenobia were recorded in many ancient sources but many of them are flawed or contain outright fabrications; the Augustan History, a late Roman collection of biographies, is the most notable unreliable source concerning the era.[14] The writer (or writers) of the Augustan History invented many fictional events and letters attributed to Zenobia, as they lacked the means to know what precisely was written or said.[14] However, when the Augustan's account deals with a known event, then the details provided by the work can be taken into consideration.[14] The work of the Byzantine chronicler Joannes Zonaras is considered an important source on the life of Zenobia, in addition to other sources.[14]

Early life and family

The Augustan History contains details on Zenobia's early life, though little of it should be believed; hunting was one of the hobbies she developed as a child, according to the aforementioned work.[15] Zenobia does not seems to have been a commoner,[15] and as a Palmyrene, she would have received a proper education fit for noble Palmyrene girls.[16] She is said to have fluently spoke, beside her Palmyrene Aramaic mother tongue, Egyptian, Greek, and to a lesser extent, Latin.[17] Probably at the age of 14, c. 255, Zenobia became the second wife of the most important Palmyrene chief, Odaenathus, the Ras (Lord) of Palmyra.[15][18]

Palmyrene society was an amalgamation of Semitic tribes (mainly Aramean and Arab), and the origin of Zenobia cannot be ascribed to one group; as a Palmyrene, she would have both Aramean and Arab ancestries.[19] The knowledge about Zenobia's ancestry and direct family connections is too slight and confused.[20] Nothing is known about the mother of the queen, while the identity of the father is much debated.[18] The Manichaean sources report the existence of "Nafsha", the sister of the "queen of Palmyra"; those sources are confused and the name "Nafsha" could be a reference to Zenobia herself.[21] The sister's existence is doubtful,[9] and the name is an Aramaic word that means "soul".[22]

Contemporary epigraphical evidence

Regarding the queen's father, different men were suggested by historians, based on archaeological evidence:

- Julius Aurelius Zenobius: his name appears on a Palmyrene inscription as a strategos of Palmyra in 231–232; based only on the similarities of the names,[18] Zenobius was suggested as the father of Zenobia by many such as the numismatist Alfred von Sallet.[23] Another argument is that the statue of Zenobius stood across the statue of the queen in the Great Colonnade at Palmyra.[3] This theory cannot be sustained, as the only gentilicium appearing on Zenobia's inscriptions was "Septimia" and not "Julia Aurelia" (which she would have bore if her fathers' gentilicium was Aurelius);[3] whether the queen changed the gentilicium to Septimia after her marriage cannot be proven.[18][23]

- Zabbai: based on her Palmyrene name (Bat Zabbai), the aforementioned name might have belonged to the queen's father; however, he could have been the ancestral head of Zenobia's family and not her direct father.[20] It is suggested by historian Trevor Bryce that Septimius Zabbai, Palmyra's garrison leader, was the father of Zenobia, or, more likely, a relative.[20]

- Antiochus: one of Zenobia's inscriptions recorded her as "Septimia Bat-Zabbai, daughter of Antiochus".[24][25] There is much speculation concerning the identity of Antiochus;[20] his ancestry is not recorded in Palmyrene inscriptions and the name was not common in Palmyra, and those facts, combined with the meaning of her Palmyrene name (daughter of Zabbai) led scholars, such as Harald Ingholt, to speculate that "Antiochus" was a distant ancestor, perhaps the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, or Antiochus VII Sidetes whose wife was the Ptolemaic Cleopatra Thea.[24][26]

In historian Richard Stoneman's view, Zenobia would not have invented such an obscure ancestry to connect herself with the ancient Macedonian rulers, as one would have invented a more direct connection (if he or she needs a fabricated ancestry).[15] Hence, in Stoneman's view, it can be assumed that Zenobia "had reason to believe it to be true" in regard to her Seleucid ancestry.[15] Historian Patricia Southern, citing that Antiochus was mentioned without a royal title or a hint of a great lineage, believes him to be a more direct ancestor or even a relative instead of a Seleucid king who lived three centuries before the time of Zenobia.[26]

In ancient sources

In the unreliable 4th-century Augustan History, Zenobia is said to have been a descendant of Cleopatra and claimed descent from the Ptolemaics.[note 1][10] Following the Palmyrene conquest of Egypt,[27] and according to the "Souda", a 10th-century Byzantine encyclopedia,[28] the Greek sophist Callinicus of Petra wrote the history of Alexandria in ten volumes and dedicated the work to Cleopatra, by whom he meant Zenobia.[note 2][30][31] Despite the legends, there is no solid evidence in the Egyptian coinage or papyri for a contemporary equation of Zenobia with Cleopatra,[32] and the relation could have been invented by the queen's enemies to discredit her.[33] The relation of Zenobia with the Ptolemaic dynasty is unlikely,[34] and the attempts in classical sources to trace the queen's ancestry back to the Ptolemaics through the Seleucids are apocryphal.[35] Zenobia's alleged claim of connection with Cleopatra seems to be politically motivated;[19] it would have given her a relation to Egypt and made her a rightful successor to the Ptolemaic throne.[36]

Arab traditions and al-Zabba'

Some Arab historians linked Zenobia with the legendary Queen of Sheba but those accounts are apocryphal.[35] Medieval Arab traditions talk about a queen of Palmyra named al-Zabba',[37] and the most romantic account about her comes from the work of al-Tabari.[38] According to him, she belonged to the Al 'Amālīq; her father was 'Amr ibn Zarib, a sheikh of the 'Amālīq who was killed by the Tanukhids.[35] Al-Tabari names a sister of al-Zabba' whom he calls "Zabibah".[35] The killer of the queen's father, Jadhimah ibn Malik, was the main antagonist and ended up being killed by al-Zabba'.[38] According to al-Tabari, al-Zabba' had a fortress along the banks of the Euphrates and also controlled Palmyra.[7]

The account of al-Tabari does not mention the Romans, Odaenathus, Vaballathus or the Sassanians;[7] it focuses on the tribes and their relations, hence it is highly legendary.[39] The account of al-Tabari is certainly based on the story of Zenobia,[7] but is probably a conflation of Zenobia's story and the story of a semi-legendary nomadic Arab queen (or queens).[40][39] The mentioned fortress of al-Zabba' was probably Halabiye (this citadel was restored by the historic Palmyrene queen and named Zenobia).[7]

Queen of Palmyra

Consort

In the early centuries AD, Palmyra was an autonomous city subordinate to Rome and part of the Syria Phoenice province.[41] In 260, the Roman emperor Valerian marched against the Persian monarch Shapur I who had invaded the eastern regions of the empire, but the Roman ruler was defeated and captured near Edessa.[42] Odaenathus kept his formal loyalty to Rome and its emperor Gallienus, Valerian's son;[43] he was declared king of Palmyra,[44] launched successful campaigns against Persia, and was crowned King of Kings of the East in 263.[45] The new Palmyrene monarch crowned his eldest son Herodianus, who was not Zenobia's offspring, as a co-ruler.[46] Beside the royal titles, many Roman titles were bestowed by the emperor upon Odaenathus who effectively ruled from the Black Sea to Palestine.[47]

The first inscription mentioning Zenobia as queen is dated two or three years after the death of her husband, hence, the exact date of when Zenobia was styled "queen of Palmyra" cannot be stated with certainty.[48] However, it is logical to assume that Zenobia was designated queen when her husband became a king.[48] As a consort, Zenobia remained in the background, unmentioned in the historical records;[49] later accounts claimed she accompanied her husband in his campaigns (as the Italian writer Giovanni Boccaccio wrote).[50] By accompanying Odenaethus, she boosted the morale of the soldiers, and gained political influence, which she utilized in her future career.[49] In 267, Odaenathus and his eldest son were assassinated while returning from a campaign; Zenobia was in her late twenties or early thirties.[46]

Possible role in Odaenathus' assassination

The Augustan History claims that Odaenathus was assassinated by a cousin named Maeonius.[51] The Augustan's author mentions that, for a time, Zenobia conspired with Maeonius, since she did not accept her stepson as the heir to his father instead of her own children.[51] However, the Augustan History does not suggest that Zenobia was involved in the events leading to her husband's murder;[52] the crime is attributed to Maeonius' degeneracy and jealousy.[51] The accounts of the Augustan History can be dismissed as fiction.[53] Modern scholarship sometimes hints that Zenobia was involved in the assassination out of ambition to rule the kingdom and opposition to her husband's pro-Roman policy; this can be dismissed as Zenboia did not reverse Odaenathus' policy during her first years on the throne following the assassination.[54]

Regent

.jpg)

The Augustan History claims that Maeonius was proclaimed emperor for a very short time before the soldiers killed him;[52] however, no inscriptions or evidence exist for Maeonius' reign.[55] At the time of the assassination, Zenobia might have been with her husband who, according to chronicler George Syncellus, was killed near Heraclea Pontica in Bithynia.[56] The transition of power seems to have been quick as Syncellus mentioned that the entire event between the assassination and the army handing the crown to Zenobia took one day.[56] Another possibility is that Zenobia was in Palmyra, but this would have reduced the likelihood of a smooth transition of power, as the soldiers might have chosen one of their officers to ascend the throne; hence, the first scenario is more probable.[56] In all cases, historical records do not mention that Zenobia fought for supremacy, and there is no evidence of a delay in the transition of the throne to Odaenathus and Zenobia's son, the ten-year-old Vaballathus.[57]

Zenobia held the reins of power in the kingdom,[58] though she never claimed to rule in her own right and acted formally as a regent for her son;[59] the latter was kept in his mother's shadow, never exercising real power.[60]

Consolidation of power

The Palmyrene monarchy was new, and loyalty to it was based on the loyalty to Odaenathus himself; hence, the transfer of power to a successor was not going to be as easy as it would have been in an old established monarchy.[61] Odaenathus seemed to have noticed this, and tried to ensure the future of his dynasty by crowning his eldest son as co-king, but the plan was cut short when both he and his designated heir were assassinated.[62] Zenobia was left to secure the Palmyrene succession and maintain the loyalty of the kingdom's subjects; she did so by emphasizing the continuity between her late husband and his adolescent successor, her son.[62] Vaballathus, with Zenobia orchestrating the process, assumed his father's royal titles immediately, and his earliest known inscription records him as the King of Kings.[62][57]

Odaenathus controlled a vast area of the Roman east, and held the highest political and military authority in the region, superseding the Roman provincial governors;[63][64] his self-established status was formalized by Emperor Gallienus,[65] who had, in practice, little choice but to acquiesce.[66] Odaenathus's power relative to the emperor and the central authorities was unprecedented and elastic, but relations remained smooth for the remainder of his life.[67] His death, however, meant that the Palmyrene rulers' authority and position had to be clarified, which led to a conflict over the interpretation of this position. The Roman court viewed Odaenathus as any other appointed Roman official who derived power from the emperor, while the Palmyrene court viewed Odaenathus' position as hereditary.[67] This conflict was the first step in setting the stage ready for war between Rome and Palmyra.[67]

Odaenathus' Roman titles, such as the dux Romanorum, corrector totius orientis or imperator totius orientis, were different from his royal eastern ones; unlike the monarchical honors, the Roman ranks were not hereditary.[68] Vaballathus had a legitimate claim to his royal titles but had no right using the Roman ones, especially that of corrector, which denoted a very senior military and provincial commander in the Roman system, and which Zenobia used for her son in his earliest known inscriptions alongside the "King of Kings" title.[62] The Roman emperors accepted the royal succession, but the assumption of the Roman military ranks antagonized the empire against Palmyra.[69] Emperor Gallienus may have decided to interfere in an attempt to regain the central authority;[25] according to the Augustan History, the praetorian prefect, Aurelius Heraclianus, was dispatched to assert imperial authority over the east, but the Palmyrene army repelled him.[70] This story is doubtful; Heraclianus took part in Gallienus's assassination in 268, and since Odaenathus was also assassinated a short time before the emperor, then the time span would not have been enough for Heraclianus to be sent to the east, fight the Palmyrenes, return to the west and then get involved in the conspiracy against the emperor.[note 3][71]

Early reign

The extent of Zenobia's territorial control during the early days is debated; in the view of historian Fergus Millar, Zenobia's authority was confined to Palmyra and Emesa until the year 270.[note 4][73] If this was the case, then the events of 270 which saw Zenobia's conquest of the entire Levant and Egypt are extraordinary.[72] It is more likely that the queen ruled the same territories controlled by her late husband,[72] a view supported by Southern and historian Udo Hartmann,[74] and backed by ancient sources such as the Roman historian Eutropius, who wrote that the queen inherited her husband's power.[72] The Augustan History also mentioned that Zenobia took control over the East during Gallienus's reign.[72][74] Further evidence supporting extended territorial gains was the statement of the Byzantine historian Zosimus, who wrote that the queen had a residence in Antioch.[note 5][72]

There is no recorded unrest accompanying the ascendance of the queen in ancient sources hostile to her, indicating that no serious opposition to the new regime existed.[note 6][76] The most obvious candidates for opposition are the Roman provincial governors, but the sources do not mention that Zenobia had to march on any of them nor that one of them tried to remove the queen from her position.[77] It seemed, according to Hartmann, that the governors and army leaders of the different eastern provinces all acknowledged and supported Vaballathus as the successor of Odaenathus.[77] During her early regency, Zenobia focused on guaranteeing the safety of the borders with Persia and pacifying the Tanukhids in Hauran.[78] To protect her borders with Persia, the queen fortified many settlements on the Euphrates, including the citadels of Halabiye (named Zenobia) and Zalabiye.[79] Circumstantial evidence exist for confrontations with the Sasanians; probably in 269, Vaballathus took the title Persicus Maximus ("The great victor in Persia"), and this might be linked with an unrecorded battle against a Persian army trying to gain control of Northern Mesopotamia.[note 7][80][81]

Expansion

In 269, while Claudius Gothicus, Gallienus's successor, was occupied defending the borders of Italy and the Balkans from Germanic invasions, Zenobia was cementing her authority; Roman officials in the East were caught between their loyalty to the emperor and Zenobia's increasing demands for their subordinance.[82]

The timing and rationale of Zenobia decision to use military force to strengthen her authority over the East is not clear;[82] the scholar Gary K. Young suggested that Roman officials refused to recognize Palmyrene authority, and thus, Zenobia's expeditions were intended to maintain Palmyrene dominance.[83] Another factor might have been the weakness of the Roman central authorities and their inability to protect the provinces; this probably convinced Zenobia that the only way to maintain the stability of the East was by assuming direct control of it.[83] Historian Jacques Schwartz tied Zenobia's actions to her desire to protect Palmyra's economic interests, which were threatened by Rome's continuous failure to protect its provinces.[84] Another point Schwartz made was conflicting economic interests; Bostra and Egypt were both receiving trade that would have otherwise passed through Palmyra.[85] It is very likely that there were attempts by the Tanukhids near Bostra and the merchants of Alexandria to rid themselves of Palmyrene domination, which led to a military response from Zenobia.[85]

Syria and the invasion of Arabia Petraea

In the spring of 270, while Claudius was preoccupied in the mountains of Thrace fighting the Goths, Zenobia sent her general, Septemius Zabdas, to Bostra, the capital of Arabia Petraea province;[82] the queen's timing seemed intentional.[86] In Arabia, the Roman governor dux, Trassus,[note 8] commanding the Legio III Cyrenaica, confronted the Palmyrenes and was routed and killed.[82] Zabdas destroyed the temple of Zeus Hammon, the legion's revered shrine;[82] an inscription written in Latin, and made after the fall of Zenobia, attests to the destruction of the temple,[88] it reads: "The temple of Iuppiter Hammon, destroyed by the Palmyrene enemies, which ... rebuilt, with a silver statue and iron doors (?)".[89] The city of Umm el-Jimal might have also been destroyed by the Palmyrenes, but in connection with their efforts to subjugate the Tanukhids.[88]

Following his victory, Zabdas marched south along the Jordan Valley and was apparently met with little opposition.[82] There is evidence that Petra was attacked, though it might have not been the main force, but a small contingent which penetrated the region.[90] In the end, both Arabia and Judaea were subdued.[90] Palmyrene dominance in Arabia is confirmed by the existence of many milestones bearing Vaballathus' name.[87] Meanwhile, the submission of Syria did not require as much effort because Zenobia enjoyed strong support there, particularly in Antioch,[91] Syria's traditional capital.[75] The invasion of Arabia coincided with the cessation of coin production in the name of Claudius by the Antiochean Mint, indicating that Zenobia had begun to tighten her grip on Syria.[91] By November 270, the mint started issuing coinage in the name of Vaballathus.[92]

The milestones in Arabia presented the Palmyrene king as a Roman governor and commander, referring to him with the titles: vir clarissimus rex consul imperator dux Romanorum.[87] This step of assuming such titles was probably meant to legitimize Zenobia's control over the province and did not yet represent an usurpation of the imperial title.[93] Up to this stage of conquest, Zenobia could still claim that she was merely acting as a representative of the emperor, who was securing the eastern lands of the empire, while the Roman monarch was preoccupied with struggles in Europe.[94] Although the use of the titles by Vaballathus practically amounted to the claiming of the imperial throne, Zenobia could still justify them and continue the mask of subordination to Rome;[68] "imperator" meant a commander of troops and was not equal to the title of an emperor (imperator caesar).[93]

Annexation of Egypt and the campaigns in Asia Minor

The invasion of Egypt is sometimes explained by Zenobia's desire to secure an alternative trade route to the Euphrates route, which was cut due to the war with Persia;[95] this proposal ignores that the Euphrates route was not completely cut, and looks past Zenobia's own personal ambition.[90] The date of the campaign is open for discussion; Zosimus placed the event after the Battle of Naissus and before Claudius' death, which sets the invasion in the summer of 270.[96] Historian Alaric Watson, on the other hand, emphasizing the works of Zonaras and Syncellus and dismissing Zosimus' account, sets the invasion in October 270, following Claudius' death.[97] For Watson, the occupation of Egypt is an opportunistic move by Zenobia, encouraged by the news of Claudius' death in August.[90][98] The appearance of the Palmyrenes at Egypt's eastern frontier would have contributed to the already existing unrest in the province, whose society was fractured, as Zenobia had both supporters and opponents amongst the local Egyptians.[90]

The Roman stance was worsened by the absence of Egypt's prefect, Tenagino Probus, who was waging a naval expedition against pirates.[90][96] According to Zosimus, the Palmyrenes were helped by an Egyptian general named Timagenes; Zabdas moved to Egypt at the head of 70,000 soldiers and defeated an army of 50,000 Romans.[98][86] Following their victory, the Palmyrenes withdrew their main force leaving a 5,000-strong garrison.[86] However, by early November,[90] Tenagino Probus returned and assembled an army; he expelled the Palmyrenes and retook Alexandria, prompting Zabdas to return.[86] The Palmyrene general aimed his thrust toward Alexandria where he seems to have enjoyed local support; the city firmly fell into the hands of Zabdas while the Roman prefect fled south.[90] The last episode of fighting took place at the Babylon fortress where Tenagino Probus took refuge; the Romans had an upper hand as they chose their camp carefully.[91] Timagenes, using his knowledge of the land, ambushed the rear of the Romans, causing the suicide of Tenagino Probus and the successful incorporation of Egypt into Palmyra.[91] The Augustan History mentions that the Blemmyes were amongst Zenobia's allies;[99] Young cites the Blemmyes' attack and occupation of Coptos in 268 as a sign of a Palmyrene-Blemmyes alliance.[100]

Only Zosimus mentioned two invasions, contrasting with many scholars who hold that there was an initial invasion with no retreat, followed by a reinforcement that took Alexandria by the end of 270.[86] During the Egyptian campaign, Rome was entangled in a succession crisis between Claudius' brother Quintillus and general Aurelian.[92] Both the Egyptian papyri and coinage confirm Palmyrene rule in Egypt; the papyri stopped using the regnal years of the emperors between September and November 270, due to the succession crisis and the ambiguity of who would take the throne.[92] By December, regnal dating was resumed and the papyri used the regnal years of the prevailing emperor, Aurelian, in addition to the years of Zenobia's son, Vaballathus.[92] Egyptian coinage began to be issued in the names of Aurelian and the Palmyrene king by November 270.[92] There is no evidence, historical or archaeological, to prove that Zenobia visited Egypt herself.[101]

Though the operations might have started under the leadership of Septimius Zabbai, Zabdas' second in command, the invasion of Aisa Minor did not commence until the arrival of the latter in the spring of 271.[102] The Palmyrenes annexed Galatia and, according to Zosimus, reached as far as Ankara.[33] However, Bithynia and the minting facilities in Cyzicus remained out of Zenobia's control; her attempts to subdue Chalcedon also failed.[102] The campaign in Asia Minor is not well-documented and the western part of the region did not come under the authority of the queen;[33][103] no inscriptions or coins bearing Zenobia's or Vaballathus' portraits were minted in the Asia Minor, and no royal Palmyrene inscriptions were found.[103] By August 271, Zabdas was back in Palmyra and the Palmyrene empire had reached its zenith.[102]

Governing

Zenobia ruled over an empire containing many different peoples; as a Palmyrene, she was accustomed to deal with multilingual and multicultural diversity as she hailed from a city that embraced many cults.[104] The queen's realm was culturally divided between eastern Semitic and a Greek zones; Zenobia tried to appease both, and seems to have successfully appealed to the different ethnic, cultural and political groups in the region.[105] The queen projected to her subject the image of a Syrian monarch, Hellenistic queen and a Roman empress, which allowed her to obtain wide support for her cause.[106]

Culture

Zenobia turned her court into a center of learning; many intellectuals and sophists were reported in Palmyra during her reign.[107] As academics immigrated to Palmyra, the city replaced the classical learning centers, such as Athens, for Syrians.[107] The court included philosophers and thinkers, the most famous of them was Longinus,[108] who immigrated in the days of Odaenathus and became Zenobia's tutor of paideia.[109][107] Many historians, such as Zosimus, accused Longinus of being the man who washed the queen's mind and convinced her to rebel.[110][109] This view presents the queen as if she were not capable of thinking for herself;[109] according to Patricia Southern, the actions of Zenobia "cannot be laid entirely at Longinus's door".[27] Other intellectuals who were associated with the court include Nicostratus of Trebizond and Callinicus of Petra.[111]

Between the second and fourth centuries, the intellectuals of Syria argued that the Greek culture did not evolve in Greece, but was adapted from the Near East.[111] This can be seen in the works of Iamblichus, who argued that the greatest Greek philosophers merely reused the ideas of the Near Easterners and Egyptians.[112] The court of Palmyra was probably dominated by this school of thought; the narrative of court intellectuals probably presented the dynasty of Palmyra as a legitimate Roman imperial dynasty, that has succeeded the Persian, Seleucid and Ptolemaic rulers who controlled the same spot of land where the Greek culture was allegedly born.[112] Nicostratus wrote a history of the Roman empire, from emperor Philip the Arab to Odaenathus, where he presented the king as a legitimate imperial successor, and highlighted his successes in contrast to the disastrous reigns of the emperors.[111]

Zenobia seems to have embarked on several building restoration projects in Egypt.[113] One of the Colossi of Memnon was reputed in antiquity to sing; this sound was probably due to the damage and cracks in the statue, and resulted from the sun rays reacting with the dew in the cracks.[114] Historian Glen Bowersock proposed that the queen was responsible for the restoration of the colossus, which silenced it; this would provide a suitable date that explains the third century accounts attesting the singing phenomenon, but the total ignorance of it in the fourth century.[115]

Religion

The Palmyrenes were pagans and worshiped a variety of Semitic gods with Bel on the head of the pantheon.[116] Zenobia accommodated both Christians and Jews,[104] and many claims exist in ancient sources regarding the beliefs of the queen.[31] The Manichaeism sources claim that Zenobia adhered to their religion.[117] It is more likely, however, that the queen simply showed great religious tolerance to all cults, in an effort to attract the support of the groups that were marginalized by Rome.[31]

Bishop Athanasius of Alexandria mentioned that Zenobia did not "hand over churches to the Jews to make them into synagogues".[118] The queen was not a Christian but she understood the power held by bishops in Christian communities.[119] In a city like Antioch, considered a representative of political control over the East, and where a large Christian community lived, Zenobia seems to have found it viable to have authority over the church, by bringing influential clerics under her auspices; this was probably the case of Paul of Samosata.[119] Zenobia might have granted Paul the rank of ducenarius, and he seems to have enjoyed the constant protection of the queen, which helped him keeping the bishopric church even after he was removed from his office as bishop of Antioch by a synod of bishops in 268.[note 9][123]

Judaism

Athanasius of Alexandria, less than a hundred years after Zenobia's reign, wrote in his work, titled "History of the Arians", that Zenobia was a "Jewess".[118] In 391, archbishop John Chrysostom also mentioned Zenobia's Jewishness and so did a Syriac chronicler living around 664, and bishop Bar Hebraeus in the 13th century.[118] French scholar Javier Teixidor accepted that Zenobia was a proselyte; in his opinion, this would explain her strained relation with the rabbis.[124] Teixidor believed that Zenobia became interested in Judaism when Longinus spoke about the philosopher Porphyry and his interest in the Old Testament.[124] Although the Talmudic sources are hostile toward Palmyra due to Odaenathus' suppression of the Jews of Nehardea,[125] Zenobia seems to have had the support of some of the Jewish communities, specially in Alexandria.[102] In Cairo, a plaque was found,[126] and originally, it bore an inscription confirming the granting of immunity to a Jewish synagogue in the last quarter of the 1st millennium BC by king Ptolemy Euergetes (whether the I or II can not be determined).[126] At a much later date, the plaque was re-inscribed to commemorate the restoration of the immunity "on the orders of the queen and king".[113][126] The plaque is undated but the letters' forms of the inscription date to a much later time than Cleopatra and Anthony's era; Zenobia and her son are the only candidates for a king and a queen ruling Egypt after the Ptolemaics.[113][127]

However, in the words of historian E. Mary Smallwood, good relations with a diaspora community do not mean that the Jews of Palestine were content with Zenobia's reign, and her rule seems to have been opposed in that region.[125] The Terumot tells the story of rabbi "Ammi" and rabbi "Samuel bar Nahmani", who visited Zenobia's court and asked for the release of a Jew named "Zeir bar Hinena", who had been seized by her orders.[128] Zenobia refused to liberate him, remarking, "Why have you come to save him? He teaches that your creator performs miracles for you. Why not let god save him?".[129] During Aurleian's destruction of Palmyra, Palestinian levies (not clear whether they were Jews or not), with their "clubs and cudgels", played a vital role in the defeat of Zenobia and the destruction of her city.[130]

There is no argument to support that Zenobia was born a Jew, evidenced by the names of her and her husband's families, which belonged to the Aramaic onomasticon.[124] The queen's alleged patronage of Paul of Samosata, who was accused of "Judaizing heresy", might have given rise to the notion that she was a proselyte.[125][31] Only Christian accounts speak about Zenobia's Jewishness, while no Jewish source mentions it.[131]

Administration

During her reign, the queen probably spent most of her time in Antioch,[101] the administrative capital of Syria.[75] Prior to the monarchy, Palmyra functioned with the institutions of a Greek city (polis);[132] it was ruled by a senate responsible for most civil affairs.[133] Odaenathus maintained the institutions of Palmyra and so did Zenobia;[134] a Palmyrene inscription made after the fall of the queen records the name of Septimius Haddudan, a Palmyrene senator.[135] However, the queen seems to have took a more absolute approach in ruling, as Septimius Worod, Odaenathus' viceroy and one of Palmyra's most important official, disappeared completely from the records following Zenobia's ascension to power.[136] The queen opened the doors of her government to eastern nobility.[104] Zenobia's most important courtier and advisers were her generals, Septemius Zabdas and Septimius Zabbai;[108] both of them were generals under Odaenathus and were granted the gentilicium "Septimius" by him.[137]

Odaenathus respected the Roman emperor's privilege to appoint provincial governors,[138] and Zenobia continued this policy during the early years of her rule.[139] The queen did not interfere in day-to-day administration but had, most probably, the power to issue commands to the governors when it came to organizing the defense of the frontiers.[140] During the rebellion, Zenobia maintained the Roman forms of administration,[33] but appointed the governors herself, most notably in Egypt,[141] where Julius Marcellinus took office in 270 and was followed by Statilius Ammianus in 271.[note 10][140]

Agreement with Rome

In the beginning, Zenobia tried not to provoke Rome by claiming to herself and to her son the titles inherited from Odaenathus, and trying to appear as a subject of Rome and a protector of its eastern frontiers.[78] Following her expansion, she seems to have sought herself recognized by Rome as a partner to the emperor, and protector of the eastern half of the empire, by showing her son subordinate to the emperor.[143][94][144] Starting in late 270, Zenobia minted coinage bearing the portraits of Aurelian and Vaballathus jointly, but only Aurelian was titled emperor while Vaballathus was titled king.[143] The regnal year in early samples of the coinage belonged only to Aurelian.[143] By march 271, however,[145] and despite showing Aurelian as the prime monarch by naming him first in the dating formulae, the coinage started to be issued bearing Vaballathus' regnal year alongside Aurelian.[146] Starting his regnal year on the coinage in 267, three years before the emperor, Vaballthus appeared as the senior colleague to the emperor.[146]

An agreement with Aurelian allowing the Palmyrene authority is debated;[147] the notional acceptance of Aurleian to the Palmyrene rule in Egypt might be inferred through the Oxyrhynchus' papyri, which is dated by the regnal years of both the emperor and Vaballthus.[143][148] However, no proof for a formal agreement exists, and the evidence is based only on the joint coinage and papyri dating.[147] It is unlikely that Aurelian would have accepted such form of power sharing;[143] he was powerless to do anything during the year 271 due to the constant crisis in the west, and his apparent condoning of Zenobia's actions might have been a trick to give her a false sense of security while he prepared for war.[147][143] Another reason for the apparent toleration on the side of Aurelian might be his desire to ensure the constant supplies of Egyptian grains to Rome;[149] it is not recorded that such supplies were cut, and the ships in 270 sailed as usual to Rome.[141] Some modern scholars, such as Harold Mattingly, suggested that it was Cladius Gothicus who concluded a formal agreement with Zenobia, and that Aurelian ignored it.[32]

Empress

In August 271, an inscription honoring Zenobia in Palmyra styled her "eusebes" (the pius);[145] this was a title for Roman empresses and can be seen as a step on the way to claim imperial dignity.[150] In the same period, an inscription mentions Zenobia as sebaste, the Greek equivalent of empress (Latin "Augusta"); yet, the inscription still acknowledged the Roman emperor.[150] In Egypt, also from late 271, a grain receipt listed both Aurelian and Vaballathus on equal foot, calling them both Augusti.[150] Finally, Palmyra officially broke with Rome;[151] in April 272, the Alexandrian mint removed Aurelian's portrait from the coins, and issued new tetradrachms in the name of Vaballathus and Zenobia, who were called unequivocally Augustus and Augusta, and the same happened in Antioch and its minting facilities.[150]

The assumption of imperial titles by Zenobia meant the final breakup with Aurelian, and the declaration of an open rebellion or usurpation.[152] The chronology of events during this period, and why Zenobia chose to declare herself empress, is vague;[153] in the second half of 271,[154] Aurelian marched to the East but was delayed by the Goths in the Balkan,[152] and this might have alarmed the queen, leading her to claim the imperial title.[153] It is also probable that Zenobia predicted the inevitable open conflict with Aurelian and decided that, hiding behind a mask of subordination, will be useless;[155] the assumption of the imperial title would be a part of the queen's effort to resist Aurelian, by assuming full authority to rally the soldiers to her cause.[155] In all probabilities, the launch of Aurelian's campaign seems to be the main reason for the Palmyrene imperial declaration and the dropping of the Roman emperor's portrait from coins.[150][84]

Downfall

The official usurpation started at the end of March-beginning of April 272, and ended by August of the same year.[156] Aurelian wintered the season of 271–272 in Byzantium,[157] and crossed the Bosporus to Asia Minor probably in April 272;[158] Galatia fell easily as the Palmyrene garrisons seem to have withdrew, and the city of Ankara, a provincial capital, was regained without struggle.[159] All the cities in Asia Minor opened their doors to the Roman emperor; only Tyana offered some resistance before surrendering, clearing the path for Aurelian to invade Syria, the heartland of the Palmyrene empire.[160] Simultaneously, an expedition reached Egypt in May 272; by early June, Alexandria was taken by the Romans and the rest of Egypt by the third week of June.[159] Zenobia seems to have withdrew most of her armies from Egypt to focus on Syria, which, if lost, will mean the end of Palmyra.[158]

In May 272, Aurelian entered Syria and headed toward Antioch.[161] There, Zabdas prepared to fight the Roman emperor at the head of the Palmyrene army; the Battle of Immae took place 40 kilometers north of Antioch, and Aurelian emerged victorious.[161][162] Zenobia was waiting in Antioch, and when Zabdas came back defeated, she ordered the army retreat to Emesa during the night.[163] To conceal the disaster and make her flight safer, she spread the news that she had captured the Roman emperor, and Zabdas found a man who looked like Aurelian, then paraded him in the streets of Antioch.[164] The next day, the Roman emperor entered Antioch and spent sometime before marching south.[163] After defeating a Palmyrene garrison south of Antioch,[165] Aurelian continued his march to meet Zenobia in the Battle of Emesa.[165]

At Emesa, the full power of Palmyra assembled, around 70,000 soldiers gathered in the plain of the city; the Romans were almost routed and defeated, but the Palmyrenes, in their initial thrill of victory, hastened their advance which broke their lines and enabled the Roman infantry of attacking their flank.[165] Defeated, Zenobia headed to her capital on the advice of her war council, leaving her treasury behind.[166] In Palmyra, the queen prepared for the siege;[167] Aurelian blockaded any route for food supplies,[168] and there were probably some unsuccessful negotiations.[169] The Augustan History claims that Zenobia declared she will fight Aurelian with the help of her allies, the Persians; this story is most probably part of Aurelian's propaganda, to imply that Zenobia was connected with Rome's greatest enemy.[169] If such an alliance existed, then a much larger frontier war would have erupted, but no Persian army was sent.[169] As the situation worsened, the queen decided to leave the city and heads to Persia, where she planned to ask Palmyra's former enemy for help; according to Zosimus; she rode a "female camel, the fastest of its breed and faster than any horse".[166][170]

Captivity and fate

Aurelian learned of Zenobia's departure and sent a contingent that captured the queen before she could cross the Euphrates river to Persia;[170] Palmyra capitulated soon after the news of what happened to the Zenobia reached it in August 272.[note 11][172][135] Aurelian sent Zenobia and her son to Emesa to face trial, and they were followed by most of Palmyra's court elite, including Longinus.[173] The Augustan History and Zosimus claimed that the queen laid all the blame for her actions on her advisers; there are no contemporary sources to describe the trial in Emesa, only hostile Roman sources.[173] The queen's reported cowardliness in defeat was probably part of Aurelian's propaganda, as it would have benefited him to portray Zenobia as a selfish woman, and a traitor to her men, thus, causing the Palmyrenes to lose faith in their queen, rather than hailing her as a hero.[173] The Roman emperor had most of his prisoners executed, but spared the queen and her son out of his desire to display her in his planned triumph.[174]

Zenobia's fate after Emesa is shrouded with uncertainty, and ancient historians provide conflicting accounts.[175] For example, Zosimus wrote that Zenobia died on her way to Rome, before crossing the Bosporus; according to this account, the queen either contracted a sickness, or starved herself to death.[175] Chronicler John Malalas wrote that Aurelian humiliated Zenobia by parading her through the eastern cities on a dromedary; in Antioch, the Roman emperor had his prisoner chained, and seated on a dais he built in the hippodrome for three days, to be displayed in front of the city's populace.[175][176] Malalas ends his account by mentioning that Zenobia appeared in Aurelian's triumph, then was beheaded.[177]

Most ancient historians agree that Zenobia was displayed in the triumph in 274, and most modern scholars accept this.[177] Zosimus is the only one to write that the queen died before reaching Rome, and his account regarding this event should be rejected.[178] A public humiliation as mentioned by Malalas is a possible scenario, as Aurelian might have wanted to make everyone know that the rebellion was punished and crushed.[175] However, only Malalas mentions the beheading, while all other historians mention that her life was spared following the triumph.[177] The Augustan History mentions that Aurelian gave Zenobia a villa in Tibur near Hadrian's Villa, where she lived with her children.[179][180] Zonaras wrote that Zenobia married a nobleman,[181] while Syncellus wrote that she married a Roman senator.[179] The house allegedly occupied by Zenobia became a tourist attraction in Rome.[182]

Descendants and titles

From her union with Odaenathus, Zenobia bore children beside Vaballathus:

- Harian II: his image appears on a seal impression along with his older brother Vaballathus as the sons of Zenobia; his identity is much debated.[183] Historian David Potter suggested that Harian II is the same as Herodianus who was crowned in 263.[note 12][186]

- Herennianus and Timolaus: the two were mentioned in the Augustan History and are not attested in any other source;[183] Herennianus might be a conflation of Hairan and Herodianus, while Timolaus is most probably a fabrication,[53] although historian Dietmar Kienast suggested that he might be Vaballathus.[187]

An inscription from Palmyra records the name of Septimius Antiochus, "Zenobia's son"; this has led to a controversy between scholars.[188] He could have been Zenobia's son, a younger brother of Vaballathus, but he could have also been presented in this manner for political reasons, since he was proclaimed emperor in 273, when Palmyra revolted against the Romans for a second time.[188] If Antiochus was really a son of Zenobia, then, most probably, he was a little child and an offspring by a man other than Odaenathus; this can be supported by the account of Zosimus, who described Antiochus as insignificant, a description that perfectly fit a five-year-old boy.[189]

According to the Augustan History, Zenobia's descendants were among the nobility of Rome in the days of Valens.[190] Both Eutropius and Jerome testified to the existence of Zenobia's descendants in Rome at their times (fourth and fifth centuries).[182][180] Those descendants might have been the result of her union with the alleged Roman spouse, or former offspring who came with her from Palmyra, but those theories are highly speculative.[191] Zonaras is the only one to mention that Zenobia had daughter;[191] he wrote that one of them wedded Aurelian, who married the queen's other daughters to distinguished Romans.[181] The Roman emperor marrying Zenobia's daughter should be considered pure fiction, according to Patricia Southern.[179]

Zenobia owed her elevated position to the minority of her son.[192] An inscription on a milestone, found along the road between Palmyra and Emesa, and dated to the early days of the queen's reign,[193] mentions Zenobia as the "illustrious queen, mother of the king of kings";[25] this was the first inscription to mention an official position of Zenobia.[194] A lead token from Antioch mentions the Zenobia with the title of queen.[195][196] The earliest known attestation of Zenobia with the title of queen in Palmyra itself, comes from an inscription carved on the base of a statue, erected for Zenobia by Zabdas and Zabbai, and dated to August 271; it titles her as the "most illustrious and pious queen".[194][197] On an undated milestone found near Byblos, Zenobia is given the title Sebaste.[153] Despite her power, Zenobia was never mentioned as the sole monarch in Palmyra, though she was the de facto sovereign of the empire.[58] She was always associated with her husband or son in inscriptions; only in Egypt were the coins minted in the queen's name alone.[58] Lastly, Zenobia assumed the title of Augusta (empress) in 272 as her coins show.[150]

Evaluation and legacy

An evaluation of Zenobia's personality is difficult; she showed courage at a moment when the supremacy achieved by her husband was threatened; by sizing the throne, she protected the region from the power vacuum caused by Odaenathus' death.[198] She used what Odaenathus left her, and turned it into a "glittering show of strength".[199] Zenobia should not be seen as a total powermonger, nor as a selfless hero fighting for a cause; historian David Graf suggested another approach: "she took seriously the titles and responsibilities she assumed for her son and that her program was far more ecumenical and imaginative than that of her husband Odenathus, not just more ambitious".[199]

Zenobia inspired numerous scholars, academics, musicians and actors; her fame lingered in the west and is supreme in the Middle East.[19] As a heroic queen with a tragic end, she ranks alongside two other heroines, Cleopatra and Boudica.[19] The queen's legend turned her into an idol, that can be reinterpreted to accommodate the needs of a writer or a historian; hence, she can be portrayed as a freedom fighter, a hero of the oppressed or a national symbol.[9] Zenobia's reputation made her a female role model;[200] according to historian Michael Rostovtzeff, empress Catherine the Great liked to compare herself to Zenobia, being a woman who created a military and an intellectual court for herself.[192] In the 1930s, thanks to the Egyptian-based women press, Zenobia became an icon for women's magazine readers in the Arabic speaking world, where she was treated as a nationalistic strong woman leader.[201]

Zenobia's most lasting legacy is in Syria where she is a national symbol.[202] The queen became an icon in the beginnings of Syrian nationalism formation; she attained a "cult following" amongst western educated Syrians, and a novel was published by journalist Salim al-Bustani in 1871, titled "Zenobia malikat Tadmor" (Zenobia queen of Palmyra).[203] Ilyas Matar, a Syrian nationalist who wrote Syria's first history in Arabic (1874),[204][205] titled "al-'Uqud al-durriyya fi tarikh al-mamlaka al-Suriyya" (The Pearly Necklaces in the History of the Syrian Kingdom),[206] was fascinated by Zenobia, and utilized her in his book.[207] The queen inspired in the mind of Matar the thought of a new Zenobia, that would give Syria a renewed role similar to the grandeur one built by the ancient queen.[207] Another "history of Syria" was written by historian Jurji Yanni in 1881;[208] in his work, Yanni considered Zenobia a loyal "daughter of the fatherland", and a yearning tone for the "glorious past" prevails when mentioning the queen.[209] Yanni described Aurelian as the tyrant who deprived Syria of its happiness and independence by capturing its queen.[209]

In modern Syria, the queen is treated as a hero; her image appeared on the Syrian banknotes,[202] and in 1997, she was the subject of a television series titled "Al-Ababid" (anarchy).[19] The TV show gained eminent popularity in the Arabic speaking world, and was watched by millions.[19] The series was a projection over the Israeli–Palestinian conflict from a Syrian prospective, where the queen's struggle symbolized the Palestinians' struggle to gain their right of self-determination.[202] Zenobia was also the subject of a biography written by Mustafa Tlass, Syria's former minister of defense and one of the country most prominent men for thirty years.[202]

Myths, romanticism and popular culture

Harold Mattingly wrote that Zenobia is "one of the most romantic figures in history."[198] In the words of Patricia Southern: "The real Zenobia is elusive, perhaps ultimately unattainable, and novelists, playwrights and historians alike can absorb the available evidence, but still need to indulge in varied degrees of speculation."[210]

Zenobia has been a subject of romanticized and ideological history;[211] whether its ancient writers or modern, Zenobia's life was written with legends.[212] The Augustan History is the clearest example for writing Zenobia's life in an ideological manner; the writer admits that he is documenting the life of the queen simply to bash emperor Gallienus.[212] Allowing a woman to rule a part of the empire provided a clear proof that Gallienus was weak, and the writer focused on how Zenobia was a better sovereign than the emperor.[213] This changed when the Augustan History moves to the life of Claudius Gothicus, a praised victorious emperor, where the writer focused on the wars waged by Claudius on the Goths, and how he, wisely, allowed Zenobia to protect the eastern frontiers.[213] When the Augustan History reaches to the biography of Aurelian, the handling of Zenobia turns dramatically, and she is portrayed as a cowered, guilty and insolent, but proud.[213] Even her wisdom was discredited, as her actions were portrayed as the result of advisers, who easily controlled the mind of the queen.[39]

The "staunch" beauty of Zenobia was emphasized by the writer of the Augustan History, who described her as having the timidity and inconsistency of women, which were the reason behind her alleged betrayal to her advisers, in order to save herself.[214] However, the gender of the queen posed a dilemma for the Augustan History, as it cast a shadow on Aurelian's victory.[214] The writer gave Zenobia many masculine characters to compensate; this would make Aurelian appears as the conquering hero, who suppressed a dangerous Amazon queen.[214] Thus, according to the Augustan History, Zenobia possessed a clear manly voice, dressed as an emperor not as an empress, rode on horseback, was attended by eunuchs instead of ladies in waiting, marched with her army and drank with her generals, was wise and careful with money in contrast to the usual spending habits of her gender, and had the hobbies of men, mainly hunting.[215] Giovanni Boccaccio, writing in the fourteenth century, produced a fantasized account dealing with the queen, where she is portrayed as a tomboy in her childhood, who preferred wrestling with boys, wondering in the forests and killing goats, instead of playing like little girls.[216] The chastity of Zenobia was a constant theme for romanticized accounts; the Augustan History claimed that the queen disdained intercourse, and allowed Odaenathus to bed her only for the purpose of conception.[216] This alleged chastity seems to have impressed male historians; Edward Gibbon wrote that Zenobia surpassed Cleopatra in both chastity and valor,[216] while Boccaccio focused on how Zenobia was careful to protect her virginity as a child, while wrestling with boys.[216]

The travelers of the seventeenth century who visited Palmyra rekindled the Western world's romantic interest in Zenobia.[39] This interest reached its height in the mid nineteenth century, when Lady Hester Stanhope visited Palmyra and wrote about how the people treated her like the queen; she was allegedly greeted with singing and dancing, while bedouin warriors stood on the columns of the city.[17] The procession ended with a mimic coronation of Stanhope under the arch of Palmyra as the "queen of the desert".[17] William Ware was fascinated by Zenobia and wrote a fantasized account about her life.[13] Many novelists and play writers produced works about the queen, such as Haley Elizabeth Garwood and Nick Dear.[13]

Cultural depictions of Zenobia: selected works

Sculptures depicting the queen

- Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra (1857) by Harriet Hosmer, exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago.[217]

- Zenobia in Chains (1859) by Harriet Hosmer, exhibited at The Huntington.[218]

Zenobia in Literature

- Chaucer tells a condensed story of Zenobia's life in one of a series of "tragedies" in The Monk's Tale.[219][16]

- La gran Cenobia (1625) by Pedro Calderón de la Barca.[220]

- The Queen of the East (1956) by Alexander Baron.[221]

Paintings depicting the queen

- Queen Zenobia addressing her soldiers (1725–1730), by Giambattista Tiepolo.[222] This painting is part of a series of tableaux depicting Zenobia and painted by Tiepolo on the walls of the Zenobio family's palace in Venice; the aforementioned family have no familial relation with the queen.[222]

- Zenobia's last look on Palmyra (1888), by Herbert Gustave Schmalz.[223]

Operas about Zenobia

- Zenobia (1694): the first opera by Tomaso Albinoni.[224]

- Zenobia in Palmira (1725) by Leonardo Leo.[225]

- Zenobia (1761) by Johann Adolph Hasse.[226]

- Zenobia in Palmira (1789) by Pasquale Anfossi.[222]

- Zenobia in Palmira (1790) by Giovanni Paisiello.[222]

- Aureliano in Palmira (1813) by Gioachino Rossini.[227]

- Zenobia Queen of Palmyra (1882) by Silas G. Pratt.[228]

- Zenobia (2007) by Mansour Rahbani.[229]

Plays about Zenobia

- Zenobia (1995) by Nick Dear, first performed at the Young Vic as a co-production with the Royal Shakespeare Company.[230]

Songs about Zenobia

- Zenobia (1977) by Fairuz, written and composed by the Rahbani Brothers.[231]

Zenobia in Films

- Nel Segno di Roma: an Italian 1959 film starring Anita Ekberg.[232]

Notes

- ↑ The writer of the Augustan History might have based his account on the work of Ammianus Marcellinus, who wrote about the habits of men in "vaulted baths" and how they extol women "with such disgraceful flattery as the Parthians do Semiramis, the Egyptians their Cleopatras, the Carians Artemisia, or the people of Palmyra Zenobia".[10] If the Augustan writer did indeed use the words of Ammianus, then the remark about Zenobia's supposed descent loses its merit.[10]

- ↑ The conclusion that Callinicus meant Zenobia is based on the fact that the work was written following Palmyra's invasion of Egypt, combined with what is known about Zenobia's claims of decent from Cleopatra.[27] The first scholar to suggest that Cleopatra, Callinicus meant Zenobia was Aurel Stein, in 1923, and his view was accepted by many other historians.[29]

- ↑ A plausible scenario, according to David Potter, would be that a campaign was sent in 270 by Claudius Gothicus, Gallienus' successor.[70]

- ↑ An often cited argument for a limited territorial control is that the Antiochean Mint did not issue coins in the name of the queen or her son before 270.[72] However, in the opinion of Patricia Southern, this can be explained by the existence of Claudius Gothicus on the imperial throne, which made it unnecessary for the queen to issue coins in the name of her son.[72] Following Claudius' death in 270, the imperial throne was contested between his brother Quintillus and the army's candidate Aurelian, but the Antiochean mint, probably under orders from Zenobia, who apparently did not recognize Quintillus, did not issue coins for both pretenders.[72] When Aurelian prevailed, Zenobia might have found it an opportunity to declare for him, and the new coins bore the picture of Aurelian but also, for the first time, Vaballathus.[72]

- ↑ The palace was probably established by Odaenathus who crowned his son in Antioch,[72] Syria's historical capital.[75]

- ↑ The Augustan History's author wrote that emperor Aurelian sent a letter to the senate mentioning that the Egyptians, Armenians and Arabs were all so afraid of Zenobia, that they did not dare to revolt; even then, the author does not mention that the Syrians were afraid of the queen.[76]

- ↑ Ancient sources accused Zenobia of sympathizing with the Persians, claiming that she was worshiped like Persian leaders and that she drank wine with their generals;[80] those accusations cannot be sustained given the fact that Zenobia fortified the frontiers with Persia.[79]

- ↑ His name is mentioned only by John Malalas, but archaeological evidence supports the Arabian campaign.[87]

- ↑ Paul of Samosata is considered, by mainstream Christianity, a heretic, accused of denying the per-existence of Christ.[120] The earliest reference to the relation between Zenobia and Paul of Samosata comes from the 4th century work of Athanasius of Alexandria "History of the Arians".[121] According to Eusebius, Paul preferred to be called ducenarius instead of bishop.[122][119] There is evidence that he held the rank in the service of Zenobia.[123] There is no evidence, however, that Paul was invited to the Palmyrene court, and his relation with Zenobia is much exaggerated and based on later sources.[104][31] The queen might have just supported Paul as a bishop to promote religious tolerance.[104]

- ↑ One of Statilius' inscriptions is firmly dated to the spring of 272; hence, he could actually be appointed by the Romans who regained Egypt in that period.[142]

- ↑ Many ancient writers mistakenly wrote that Zenobia was captured at Immae; those include John Malalas, Rufius Festus, Jordanes, George Syncellus and Jerome.[171]

- ↑ Odaenathus eldest son is mentioned in the Augustan History as Herod; in Palmyra, he is named Hairan, while a lead token from Antioch mentions him with the name "Herodianus" as King of Kings.[184] Andreas Alföldi refused that Herodianus is the same as Herod (Hairan I); he believes that Herodianus would not have been called King of Kings in his father's life, and hence, he was Zenobia's son and succeeded his father for a short period.[185] Hatrmann believes that Herodianus is the Greek version of Hairan/Herod.[184] Potter prefer to separate Herodianus/Herod from Hairan I; he believes that Hairan I died before the birth of Herodianus who was crowned king by his father.[186]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 73.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 3173.

- 1 2 3 Sartre 2005, p. 551.

- ↑ Edwell 2007, p. 230.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 2.

- ↑ Weldon 2008, p. 106.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Millar 1993, p. 433.

- ↑ Powers 2010, p. 148.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 4 Teixidor 2005, p. 201.

- ↑ Duruy 1883, p. 295.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 Stoneman 1994, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stoneman 1994, p. 112.

- 1 2 Stoneman 1994, p. 113.

- 1 2 3 Ball 2016, p. 85.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Southern 2008, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 Bryce 2014, p. 297.

- ↑ Ball 2016, p. 121.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 264.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 117.

- 1 2 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 371.

- 1 2 3 Ando 2012, p. 209.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 5.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 97.

- ↑ Teixidor 2005, p. 206.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 188.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 263.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Watson 2004, p. 65.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 190.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 116.

- ↑ Bryce 2014, p. 298.

- 1 2 3 4 Ball 2002, p. 78.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 93.

- ↑ Rihan 2014, p. 28.

- 1 2 Bryce 2014, p. 295.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Bryce 2014, p. 296.

- ↑ Edwell 2007, p. 27.

- ↑ Ando 2012, p. 167.

- ↑ Mommsen 2005, p. 298.

- ↑ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 159.

- ↑ Butcher 2003, p. 60.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy 2009, p. 61.

- ↑ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 160.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 73.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 72.

- ↑ Franklin 2006, p. 60.

- 1 2 3 Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 81.

- 1 2 Bryce 2014, p. 292.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 58.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 78.

- ↑ Brauer 1975, p. 163.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 81.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 84.

- 1 2 3 Stoneman 1994, p. 119.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ Bryce 2014, p. 299.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Young 2003, p. 215.

- ↑ Goldsworthy 2009, p. 61.

- ↑ Vervaet 2007, p. 137.

- ↑ Young 2003, p. 214.

- 1 2 3 Ando 2012, p. 172.

- 1 2 Kulikowski 2016, p. 158.

- ↑ Andrade 2013, p. 333.

- 1 2 Potter 2014, p. 262.

- ↑ Southern 2015, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Southern 2008, p. 87.

- ↑ Millar 1971, p. 9.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 186.

- 1 2 3 Nakamura 1993, p. 141.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 88.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 89.

- 1 2 Bryce 2014, p. 299.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 91.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 92.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 267.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Watson 2004, p. 61.

- 1 2 Young 2003, p. 163.

- 1 2 Young 2003, p. 162.

- 1 2 Young 2003, p. 164.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 109.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 108.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Watson 2004, p. 62.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson 2004, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 106.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 110.

- 1 2 Bryce & Birkett-Rees 2016, p. 282.

- ↑ Smith II 2013, p. 178.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 113.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 190.

- 1 2 Teixidor 2005, p. 204.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 122.

- ↑ Young 2003, p. 76.

- 1 2 Teixidor 2005, p. 205.

- 1 2 3 4 Watson 2004, p. 64.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 117.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Southern 2008, p. 86.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 66.

- ↑ Nakamura 1993, p. 135.

- 1 2 3 Andrade 2013, p. 335.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 95.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 96.

- ↑ Schneider 1993, p. 19.

- 1 2 3 Andrade 2013, p. 336.

- 1 2 Andrade 2013, p. 337.

- 1 2 3 Bowersock 1984, p. 32.

- ↑ Bagnall 2004, p. 195.

- ↑ Bowersock 1984, p. 3132.

- ↑ Butcher 2003, p. 345.

- ↑ Ball 2016, p. 489.

- 1 2 3 Teixidor 2005, p. 217.

- 1 2 3 Teixidor 2005, p. 220.

- ↑ Macquarrie 2003, p. 149.

- ↑ Downey 2015, p. 312.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 149151.

- 1 2 Millar 1971, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Teixidor 2005, p. 218.

- 1 2 3 Smallwood 1976, p. 532.

- 1 2 3 Smallwood 1976, p. 517.

- ↑ Smallwood 1976, p. 518.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 330.

- ↑ Neusner 2010, p. 125.

- ↑ Smallwood 1976, p. 533.

- ↑ Graetz 2009, p. 529.

- ↑ Smith II 2013, p. 122.

- ↑ Smith II 2013, p. 127.

- ↑ Sivertsev 2002, p. 72.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 384.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 117.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 257.

- ↑ Ando 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 8788.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 88.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 115.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Watson 2004, p. 67.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 118.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 68.

- 1 2 Ando 2012, p. 210.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 118.

- ↑ Ando 2012, p. 211.

- ↑ Drinkwater 2005, p. 52.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Watson 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ Dignas & Winter 2007, p. 161.

- 1 2 Southern 2015, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 120.

- ↑ Potter 2014, p. 266.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 121.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 359.

- ↑ Southern 2015, p. 170.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 133.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 71.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 7172.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 268.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 73.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 74.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 137.

- 1 2 3 Watson 2004, p. 75.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 76.

- ↑ Powers 2010, p. 133.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 144.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 145.

- ↑ Downey 2015, p. 267.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 77.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 146.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 7984.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 156.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 79.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 159.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 83.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 160.

- 1 2 Bryce 2014, p. 317.

- 1 2 Banchich & Lane 2009, p. 60.

- 1 2 Southern 2015, p. 171.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 10.

- 1 2 Hartmann 2001, p. 114115116.

- ↑ Bray 1997, p. 276.

- 1 2 Potter 2014, p. 85.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 174.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 5.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 81.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 187.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 84.

- 1 2 Stoneman 1994, p. 121.

- ↑ Millar 1993, p. 172.

- 1 2 Stoneman 1994, p. 118.

- ↑ Bland 2011, p. 133.

- ↑ Cussini 2005, p. 27.

- ↑ Dodgeon & Lieu 2002, p. 77.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 87.

- 1 2 Watson 2004, p. 88.

- ↑ Slatkin 2001, p. 144.

- ↑ Booth 2011, p. 239.

- 1 2 3 4 Sahner 2014, p. 134.

- ↑ Choueiri 2013, p. 66.

- ↑ Iggers, Wang & Mukherjee 2013, p. 94.

- ↑ Abu-Manneh 1992, p. 22.

- ↑ Choueiri 2013, p. 226.

- 1 2 Choueiri 2013, p. 51.

- ↑ Pipes 1992, p. 14.

- 1 2 Choueiri 2013, p. 57.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Sartre 2005, p. 16.

- 1 2 Southern 2008, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Southern 2008, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 Watson 2004, p. 85.

- ↑ Watson 2004, p. 86.

- 1 2 3 4 Fraser 2011, p. 79.

- ↑ Kelly 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Culkin 2010, p. 167.

- ↑ Godman 1985, p. 272.

- ↑ Quintero 2016, p. 52.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 472.

- 1 2 3 4 Southern 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Stoneman 1994, p. 200.

- ↑ Southern 2008, p. 14.

- ↑ Macy 2008, p. 472.

- ↑ Hansell 1968, p. 108.

- ↑ Gallo 2012, p. 254.

- ↑ Hartmann 2001, p. 473.

- ↑ Fraser 2011, p. 86.

- ↑ Dear 2014, p. 118.

- ↑ Aliksān 1989, p. 112.

- ↑ Wood 2006, p. 59.

Sources

- Abu-Manneh, Butrus (1992). "The Establishment and dismantling of the province of Syria, 1865–1888". In Spagnolo, John P. Problems of the modern Middle East in historical perspective: essays in honour of Albert Hourani. Ithaca Press (for the Middle East Centre, St. Antony's College Oxford). ISBN 978-0-86372-164-9.

- Aliksān, Jān (1989). التشخيص والمنصة: دراسات في المسرح العربي المعاصر (in Arabic). اتحاد الكتاب العرب. OCLC 4771160319.

- Ando, Clifford (2012). Imperial Rome AD 193 to 284: The Critical Century. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0-7486-5534-2.

- Andrade, Nathanael J. (2013). Syrian Identity in the Greco-Roman World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-01205-9.

- Bagnall, Roger S. (2004). Egypt from Alexander to the Early Christians: An Archaeological and Historical Guide. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-796-2.

- Ball, Warwick (2002). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-82387-1.

- Ball, Warwick (2016). Rome in the East: The Transformation of an Empire (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-29635-5.

- Banchich, Thomas; Lane, Eugene (2009). The History of Zonaras: From Alexander Severus to the Death of Theodosius the Great. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-42473-3.

- Bland, Roger (2011). "The Coinage of Vabalathus and Zenobia from Antioch and Alexandria". The Numismatic Chronicle. The Royal Numismatic Society. 171. ISSN 2054-9202.

- Booth, Marilyn (2011). "Constructions of Syrian identity in the Women's press in Egypt". In Beshara, Adel. The Origins of Syrian Nationhood: Histories, Pioneers and Identity. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-61504-4.

- Bowersock, Glen Warren (1984). "The Miracle of Memnon". Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists. The American Society of Papyrologists. 21. ISSN 0003-1186.

- Brauer, George C. (1975). The Age of the Soldier Emperors: Imperial Rome, A.D. 244-284. Noyes Press. ISBN 978-0-8155-5036-5.

- Bray, John Jefferson (1997). Gallienus: A Study in Reformist and Sexual Politics. Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1-86254-337-9.

- Bryce, Trevor (2014). Ancient Syria: A Three Thousand Year History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-100292-2.

- Bryce, Trevor; Birkett-Rees, Jessie (2016). Atlas of the Ancient Near East: From Prehistoric Times to the Roman Imperial Period. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-56210-8.

- Butcher, Kevin (2003). Roman Syria and the Near East. Getty Publications. ISBN 978-0-89236-715-3.

- Choueiri, Youssef (2013) [1989]. Modern Arab Historiography: Historical Discourse and the Nation-State (revised ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-86862-7.

- Culkin, Kate (2010). Harriet Hosmer: A Cultural Biography. University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-839-6.

- Cussini, Eleonora (2005). "Beyond the spindle: Investigating the role of Palmyrene women". In Cussini, Eleonora. A Journey to Palmyra: Collected Essays to Remember Delbert R. Hillers. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12418-9.

- Dear, Nick (2014). Nick Dear Plays 1: Art of Success; In the Ruins; Zenobia; Turn of the Screw. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-31843-8.

- Dignas, Beate; Winter, Engelbert (2007). Rome and Persia in Late Antiquity: Neighbours and Rivals. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-84925-8.

- Dodgeon, Michael H; Lieu, Samuel N. C (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 226-363: A Documentary History. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96113-9.

- Downey, Glanville (2015) [1961]. History of Antioch. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-7773-7.

- Drinkwater, John (2005). "Maximinus to Diocletian and the 'crisis'". In Bowman, Alan K.; Garnsey, Peter; Cameron, Averil. The Crisis of Empire, AD 193-337. The Cambridge Ancient History. 12. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-30199-2.

- Duruy, Victor (1883) [1855]. "II". History of Rome and of the Roman people, from its origin to the Invasion of the Barbarians. VII. Translated by C. F. Jewett Publishing Company. Jewett. OL 24136924M.

- Edwell, Peter (2007). Between Rome and Persia: The Middle Euphrates, Mesopotamia and Palmyra Under Roman Control. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-09573-5.

- Franklin, Margaret Ann (2006). Boccaccio's Heroines: Power and Virtue in Renaissance Society. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7546-5364-6.

- Fraser, Antonia (2011) [1988]. Warrior Queens: Boadicea's Chariot. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-1-78022-070-3.

- Gallo, Denise (2012). Gioachino Rossini: A Research and Information Guide. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-84701-2.

- Godman, Peter (1985) [1983]. "Chaucer and Boccaccio's Latin Works". In Boitani, Piero. Chaucer and the Italian Trecento. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31350-6.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian (2009). The Fall Of The West: The Death Of The Roman Superpower. Hachette UK. ISBN 978-0-297-85760-0.

- Graetz, Heinrich (2009) [1893]. Lowy, Bella, ed. History of the Jews: From the Reign of Hyrcanus (135 B. C. E) to the Completion of the Babylonian Talmud (500 C. E. ). II. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 978-1-60520-942-5.

- Hansell, Sven Hostrup (1968). Works for solo voice of Johann Adolph Hasse, 1699–1783. Detroit studies in music bibliography. 12. Information Coordinators. OCLC 245456.

- Hartmann, Udo (2001). Das palmyrenische Teilreich (in German). Franz Steiner Verlag. ISBN 978-3-515-07800-9.

- Iggers, Georg G; Wang, Q. Edward; Mukherjee, Supriya (2013). A Global History of Modern Historiography. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-89501-5.

- Kelly, Sarah E. (2004). "Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra". In Pearson, Gail A. Notable Acquisitions at the Art Institute of Chicago. 2. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-86559-209-4.

- Kulikowski, Michael (2016). Imperial Triumph: The Roman World from Hadrian to Constantine. Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-84765-437-3.

- Macquarrie, John (2003). Stubborn Theological Questions. Hymns Ancient and Modern Ltd. ISBN 978-0-334-02907-6.

- Macy, Laura Williams (2008). The Grove Book of Opera Singers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533765-5.

- Millar, Firgus (1971). "Paul of Samosata, Zenobia and Aurelian: the Church, Local Culture and Political Allegiance in Third-Century Syria". Journal of Roman Studies. The Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 61. OCLC 58727367.

- Millar, Fergus (1993). The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-77886-3.

- Mommsen, Theodor (2005) [1882]. Wiedemann, Thomas, ed. A History of Rome Under the Emperors. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-62479-9.

- Nakamura, Byron (1993). "Palmyra and the Roman East". Greek, Roman, and Byzantine Studies. Duke University, Department of Classical Studies. 34. ISSN 0017-3916.

- Neusner, Jacob (2010). Narrative and Document in the Rabbinic Canon: The Two Talmuds. 2. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-7618-5211-7.

- Pipes, Daniel (1992) [1990]. Greater Syria: The History of an Ambition. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-536304-3.

- Potter, David S (2014). The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-69477-8.