Thessaloniki

| Thessaloniki Θεσσαλονίκη Salonica | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

|

| |||

| |||

|

Nickname(s): The co-capital, The Nymph of the Thermaic Gulf | |||

Thessaloniki | |||

| Coordinates: GR 40°39′N 22°54′E / 40.65°N 22.9°ECoordinates: GR 40°39′N 22°54′E / 40.65°N 22.9°E | |||

| Country | Greece | ||

| Geographic region | Macedonia | ||

| Administrative region | Central Macedonia | ||

| Regional unit | Thessaloniki | ||

| Founded | 315 BC (2331 years ago) | ||

| Incorporated | Oct. 1912 (104 years ago) | ||

| Municipalities | 7 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor-council government | ||

| • Mayor | Yiannis Boutaris (Ind.) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Municipality | 19.307 km2 (7.454 sq mi) | ||

| • Urban | 111.703 km2 (43.129 sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 1,285.61 km2 (496.38 sq mi) | ||

| Highest elevation | 250 m (820 ft) | ||

| Lowest elevation | 0 m (0 ft) | ||

| Population (2011)[1] | |||

| • Municipality | 325,182 | ||

| • Rank | 2nd urban, 2nd metro in Greece | ||

| • Urban | 788,952 | ||

| • Urban density | 7,100/km2 (18,000/sq mi) | ||

| • Metro | 1,012,297 | ||

| • Metro density | 790/km2 (2,000/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym(s) | Thessalonian | ||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||

| Postal codes | 53xxx, 54xxx, 55xxx, 56xxx | ||

| Telephone | 231 | ||

| Vehicle registration | NAx-xxxx to NXx-xxxx | ||

| Patron saint | Saint Demetrius (26 October) | ||

| Gross metropolitan product (2009)[2] | €19.9 billion | ||

| • Per capita | €17,200 | ||

| Website | www.thessaloniki.gr | ||

Thessaloniki (Greek: Θεσσαλονίκη [θesaloˈnici]) is the second-largest city in Greece and the capital of Greek Macedonia, the administrative region of Central Macedonia and the Decentralized Administration of Macedonia and Thrace.[3][4] Its nickname is η Συμπρωτεύουσα (Symprotévousa), literally "the co-capital",[5] a reference to its historical status as the Συμβασιλεύουσα (Symvasilévousa) or "co-reigning" city of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, alongside Constantinople.[6]

The municipality of Thessaloniki, the historical center, had a population of 325,182 in 2011,[1] while the Thessaloniki Urban Area had a population of 788,952.[1] and the Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area had 1,012,297 inhabitants in 2011.[1]

Thessaloniki is Greece's second major economic, industrial, commercial and political centre, and a major transportation hub for the rest of southeastern Europe;[7] its commercial port is also of great importance for Greece and the southeastern European hinterland.[7] The city is renowned for its festivals, events and vibrant cultural life in general,[8] and is considered to be Greece's cultural capital.[8] Events such as the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair, the Thessaloniki International Film Festival, and the Thessaloniki Song Festival are held annually, while the city also hosts the largest bi-annual meeting of the Greek diaspora.[9] Thessaloniki was the 2014 European Youth Capital.[10]

The city of Thessaloniki was founded in 315 BC by Cassander of Macedon. An important metropolis by the Roman period, Thessaloniki was the second largest and wealthiest city of the Byzantine Empire. It was conquered by the Ottomans in 1430, and passed from the Ottoman Empire to modern Greece on 8 November 1912.

Thessaloniki is home to numerous notable Byzantine monuments, including the Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as well as several Roman, Ottoman and Sephardic Jewish structures. The city's main university, Aristotle University, is the largest in Greece and the Balkans.[11]

Thessaloniki is a popular tourist destination in Greece. For 2013, National Geographic Magazine included Thessaloniki in its top tourist destinations worldwide,[12] while in 2014 Financial Times FDI magazine (Foreign Direct Investments) declared Thessaloniki as the best mid-sized European city of the future for human capital and lifestyle.[13][14] Among street photographers, the center of Thessaloniki is also considered the most popular destination for street photography in Greece.[15]

Etymology

All variations of the city's name derive from the original (and current) appellation in Ancient Greek, i.e. Θεσσαλονίκη (IPA: [tʰes.sa.lo.nǐː.kɛː]; from Θεσσαλός, Thessalos, and Νίκη, Nikē), literally translating to "Thessalian Victory". The name of the city came from the name of a princess, Thessalonike of Macedon, half sister of Alexander the Great, so named because of her birth on the day of the Macedonian victory at the Battle of Crocus Field (353/352 BCE).[16]

The alternative name Salonica (also Thessalonica or Salonika) derives from the variant form Σαλονίκη (Saloníki) in colloquial Greek speech, and has given rise to the form of the city's name in several languages. Names in other languages prominent in the city's history include Солѹнь (Solun) in Old Church Slavonic, סלוניקה (Salonika) in Ladino, Selanik (also Selânik) in Turkish (سلانیك in Ottoman Turkish), Solun (also written as Солун) in the local and neighboring South Slavic languages, Салоники (Saloníki) in Russian, and Sãrunã in Aromanian. In local speech, the city's name is typically pronounced with a dark and deep L characteristic of Macedonian Greek accent.[17][18]

The name often appears in writing in the abbreviated form Θεσ/νίκη.[19]

History

From antiquity to the Roman Empire

.jpg)

The city was founded around 315 BC by the King Cassander of Macedon, on or near the site of the ancient town of Therma and 26 other local villages.[20] He named it after his wife Thessalonike,[21] a half-sister of Alexander the Great and princess of Macedon as daughter of Philip II. Under the kingdom of Macedon the city retained its own autonomy and parliament[22] and evolved to become the most important city in Macedon.[21]

After the fall of the kingdom of Macedon in 168 BC, Thessalonica became a free city of the Roman Republic under Mark Antony in 41 BC.[21][23] It grew to be an important trade-hub located on the Via Egnatia,[24] the road connecting Dyrrhachium with Byzantium,[25] which facilitated trade between Thessaloniki and great centers of commerce such as Rome and Byzantium.[26] Thessaloniki also lay at the southern end of the main north-south route through the Balkans along the valleys of the Morava and Axios river valleys, thereby linking the Balkans with the rest of Greece.[27] The city later became the capital of one of the four Roman districts of Macedonia.[24] Later it became the capital of all the Greek provinces of the Roman Empire because of the city's importance in the Balkan peninsula.

At the time of the Roman Empire, about 50 A.D., Thessaloniki was also an important center for the spread of Christianity; while on his second missionary journey, Paul the Apostle visited this city's chief synagogue on three Sabbaths and sowed the seeds for Thessaloniki's first Christian church. Later, Paul wrote two letters to the new church at Thessaloniki, preserved in the Bible canon as First and Second Thessalonians. Some scholars hold that the First Epistle to the Thessalonians is the first written book of the New Testament.[28]

In 306 AD, Thessaloníki acquired a patron saint, St. Demetrius, a native of Thessalonica whom Galerius put to death. A basilical church was first built in the 5th century AD dedicated to St.Demetrius.

When the Roman Empire was divided into the tetrarchy, Thessaloniki became the administrative capital of one of the four portions of the Empire under Galerius Maximianus Caesar,[29][30] where Galerius commissioned an imperial palace, a new hippodrome, a triumphal arch and a mausoleum among others.[30][31][32]

In 379, when the Roman Prefecture of Illyricum was divided between the East and West Roman Empires, Thessaloniki became the capital of the new Prefecture of Illyricum.[24] In 390, Gothic troops under the Roman Emperor Theodosius I, led a massacre against the inhabitants of Thessalonica, who had risen in revolt against the Gothic soldiers. With the Fall of Rome in 476, Thessaloniki became the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire.[26]

Byzantine era and Middle Ages

From the first years of the Byzantine Empire, Thessaloniki was considered the second city in the Empire after Constantinople,[33][34][35] both in terms of wealth and size.[33] with a population of 150,000 in the mid-12th century.[36] The city held this status until it was transferred to Venice in 1423. In the 14th century, the city's population exceeded 100,000 to 150,000,[37][38][39] making it larger than London at the time.[40]

During the 6th and 7th centuries, the area around Thessaloniki was invaded by Avars and Slavs, who unsuccessfully laid siege to the city several times, as narrated in the Miracles of Saint Demetrius.[41] Traditional historiography stipulates that many Slavs settled in the hinterland of Thessaloniki;[42] however, this migration was allegedly on a much smaller scale than previously thought.[42][42][43] In the 9th century, the Byzantine Greek missionaries Cyril and Methodius, both natives of the city, created the first literary language of the Slavs, the Glagolic alphabet, most likely based on the Slavic dialect used in the hinterland of their hometown.[44][45][46][47][48]

An Arab naval attack in 904 resulted in the sack of the city.[49] The economic expansion of the city continued through the 12th century as the rule of the Komnenoi emperors expanded Byzantine control to the north. Thessaloniki passed out of Byzantine hands in 1204,[50] when Constantinople was captured by the forces of the Fourth Crusade and incorporated the city and its surrounding territories in the Kingdom of Thessalonica[51] — which then became the largest vassal of the Latin Empire. In 1224, the Kingdom of Thessalonica was overrun by the Despotate of Epirus, a remnant of the former Byzantine Empire, under Theodore Komnenos Doukas who crowned himself Emperor,[52] and the city became the Despotate's capital.[52][53] This era of the Despotate of Epirus is also known as the Empire of Thessalonica.[52][54][55] Following his defeat at Klokotnitsa however in 1230,[52][56] the Empire of Thessalonica became a vassal state of the Second Bulgarian Empire until it was recovered again in 1246, this time by the Nicaean Empire.[52]

In 1330, on the emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, founded in the city the "School of Thessaloniki" an institute of higher education, which operated for almost a century, since after the Ottoman conquest in 1430, served as "Greek school of Thessaloniki", as a secondary school to meet the needs of the new era. In the mid Ottoman period it upgraded as "Higher School" and to 1873 served as "Central Urban School of Thessaloniki". Then with the title "Gymnasium of Thessaloniki" functioned until the liberation in 1912. Since then, it operates as " 1st High School of Thessaloniki" and having a continuous operating history of nearly 700 years is one of the oldest educational institutions of Europe, and the oldest of Greek education. In 1342,[57] the city saw the rise of the Commune of the Zealots, an anti-aristocratic party formed of sailors and the poor,[58] which is nowadays described as social-revolutionary.[57] The city was practically independent of the rest of the Empire,[57][58][59] as it had its own government, a form of republic.[57] The zealot movement was overthrown in 1350 and the city was reunited with the rest of the Empire.[57]

In 1423, Despot Andronicus, who was in charge of the city, ceded it to the Republic of Venice with the hope that it could be protected from the Ottomans who were besieging the city (there is no evidence to support the oft-repeated story that he sold the city to them). The Venetians held Thessaloniki until it was captured by the Ottoman Sultan Murad II on 29 March 1430.[60]

Ottoman period

When Sultan Murad II captured Thessaloniki and sacked it in 1430, contemporary reports estimated that about one-fifth of the city's population was enslaved.[61] Upon the conquest of Thessaloniki, some of its inhabitants escaped,[62] including intellectuals such as Theodorus Gaza "Thessalonicensis" and Andronicus Callistus.[63] However, the change of sovereignty from the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman one did not affect the city's prestige as a major imperial city and trading hub.[64][65] Thessaloniki and Smyrna, although smaller in size than Constantinople, were the Ottoman Empire's most important trading hubs.[64] Thessaloniki's importance was mostly in the field of shipping,[64] but also in manufacturing,[65] while most of the city's trade was controlled by ethnic Greeks.[64]

During the Ottoman period, the city's population of mainly Greek Jews, then as now called Romaniotes, and Ottoman Muslims (including those of Turkish and Albanian origin, as well as Bulgarian Muslim and Greek Muslim convert origin) grew substantially. According to the 1478 census Selânik (سلانیك), as the city came to be known in Ottoman Turkish, had a population of 4,320 Muslims, 6,094 Greek Orthodox and some Catholics. No Jews were recorded in the census. Soon after the turn of the 15th to 16th century, however, nearly 20,000 Sephardic Jews immigrated to Greece from the Iberian Peninsula following their expulsion from Spain by the 1492 Alhambra Decree.[66] By c. 1500, the numbers had grown to 7,986 Greeks, 8,575 Muslims, and 3,770 Jews. By 1519, Sephardic Jews numbered 15,715, 54% of the city's population. Some historians consider the Ottoman regime's invitation to Jewish settlement was a strategy to prevent the ethnic Greek population (Eastern Orthodox Christians) from dominating the city.[67]

Thessaloniki was the capital of the Sanjak of Selanik within the wider Rumeli Eyalet (Balkans)[68] until 1826, and subsequently the capital of Selanik Eyalet (after 1867, the Selanik Vilayet).[69][70] This consisted of the sanjaks of Selanik, Serres and Drama between 1826 and 1912.[71] Thessaloniki was also a Janissary stronghold where novice Janissaries were trained. In June 1826, regular Ottoman soldiers attacked and destroyed the Janissary base in Thessaloniki while also killing over 10,000 Janissaries, an event known as The Auspicious Incident in Ottoman history.[72] From 1870, driven by economic growth, the city's population expanded by 70%, reaching 135,000 in 1917.[73]

The last few decades of Ottoman control over the city were an era of revival, particularly in terms of the city's infrastructure. It was at that time that the Ottoman administration of the city acquired an "official" face with the creation of the Command Post[74] while a number of new public buildings were built in the eclectic style in order to project the European face both of Thessaloniki and the Ottoman Empire.[74][75] The city walls were torn down between 1869 and 1889,[76] efforts for a planned expansion of the city are evident as early as 1879,[77] the first tram service started in 1888[78] and the city streets were illuminated with electric lamp posts in 1908.[79] In 1888 Thessaloniki was connected to Central Europe via rail through Belgrade, Monastir in 1893 and Constantinople in 1896.[77]

20th century and since

In the early 20th century, Thessaloniki was in the center of radical activities by various groups; the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization, founded in 1897,[80] and the Greek Macedonian Committee, founded in 1903.[81] In 1903 an anarchist group known as the Boatmen of Thessaloniki planted bombs in several buildings in Thessaloniki, including the Ottoman Bank, with some assistance from the IMRO. The Greek consulate in Ottoman Thessaloniki (now the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle) served as the center of operations for the Greek guerillas. In 1908 the Young Turks movement broke out in the city, sparking the Young Turk Revolution.[82]

As the First Balkan War broke out, Greece declared war on the Ottoman Empire and expanded its borders. When Eleftherios Venizelos, Prime Minister at the time, was asked if the Greek army should move towards Thessaloniki or Monastir (now Bitola, Republic of Macedonia), Venizelos replied "Θεσσαλονίκη με κάθε κόστος!" (Thessaloniki, at all costs!).[83] As both Greece and Bulgaria wanted Thessaloniki, the Ottoman garrison of the city entered negotiations with both armies.[84] On 8 November 1912 (26 October Old Style), the feast day of the city's patron saint, Saint Demetrius, the Greek Army accepted the surrender of the Ottoman garrison at Thessaloniki.[85] The Bulgarian army arrived one day after the surrender of the city to Greece and Tahsin Pasha, ruler of the city, told the Bulgarian officials that "I have only one Thessaloniki, which I have surrendered".[84] After the Second Balkan War, Thessaloniki and the rest of the Greek portion of Macedonia were officially annexed to Greece by the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913.[86] On 18 March 1913 George I of Greece was assassinated in the city by Alexandros Schinas.[87]

In 1915, during World War I, a large Allied expeditionary force established a base at Thessaloniki for operations against pro-German Bulgaria.[88] This culminated in the establishment of the Macedonian Front, also known as the Salonika Front.[89][90] In 1916, pro-Venizelist Greek army officers and civilians, with the support of the Allies, launched an uprising,[91] creating a pro-Allied[92] temporary government by the name of the "Provisional Government of National Defence"[91][93] that controlled the "New Lands" (lands that were gained by Greece in the Balkan Wars, most of Northern Greece including Greek Macedonia, the North Aegean as well as the island of Crete);[91][93] the official government of the King in Athens, the "State of Athens",[91] controlled "Old Greece"[91][93] which were traditionally monarchist. The State of Thessaloniki was disestablished with the unification of the two opposing Greek governments under Venizelos, following the abdication of King Constantine in 1917.[88][93]

On 30 December 1915 an Austrian air raid on Thessaloniki alarmed many town civilians and killed at least one person, and in response the Allied troops based there arrested the German and Austrian and Bulgarian and Turkish vice-consuls and their families and dependents and put them on a battleship, and billeted troops in their consulate buildings in Thessaloniki.[94]

Most of the old center of the city was destroyed by the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, which was started accidentally by an unattended kitchen fire on 18 August 1917.[95] The fire swept through the centre of the city, leaving 72,000 people homeless; according to the Pallis Report, most of them were Jewish (50,000). Many businesses were destroyed, as a result, 70% of the population were unemployed.[95] Two churches and many synagogues and mosques were lost. Nearly one-quarter of the total population of approximately 271,157 became homeless.[95] Following the fire the government prohibited quick rebuilding, so it could implement the new redesign of the city according to the European-style urban plan[6] prepared by a group of architects, including the Briton Thomas Mawson, and headed by French architect Ernest Hébrard.[95] Property values fell from 6.5 million Greek drachmas to 750,000.[96]

After the defeat of Greece in the Greco-Turkish War and during the break-up of the Ottoman Empire, a population exchange took place between Greece and Turkey.[92] Over 160,000 ethnic Greeks deported from the former Ottoman Empire - particularly Greeks from western Asia Minor and Pontic Greeks as well as Caucasus Greeks from various parts of Eastern Anatolia and the South Caucasus - were resettled in the city,[92] changing its demographics. Additionally many of the city's Muslims, including Ottoman Greek Muslims, were deported to Turkey, ranging at about 20,000 people.[97]

During World War II Thessaloniki was heavily bombarded by Fascist Italy (with 232 people dead, 871 wounded and over 800 buildings damaged or destroyed in November 1940 alone),[98] and, the Italians having failed in their invasion of Greece, it fell to the forces of Nazi Germany on 8 April 1941[99] and remained under German occupation until 30 October 1944 when it was liberated by the Greek People's Liberation Army.[100] The Nazis soon forced the Jewish residents into a ghetto near the railroads and on 15 March 1943 began the deportation process of the city's 56,000 Jews to its Nazi concentration camps.[101][102] They deported over 43,000 of the city's Jews in concentration camps,[101] where most were killed in gas chambers. The Germans also deported 11,000 Jews to forced labor camps, where most perished.[103] Only 1,200 Jews live in the city today.

The importance of Thessaloniki to Nazi Germany can be demonstrated by the fact that, initially, Hitler had planned to incorporate it directly in the Third Reich[104] (that is, make it part of Germany) and not have it controlled by a puppet state such as the Hellenic State or an ally of Germany (Thessaloniki had been promised to Yugoslavia as a reward for joining the Axis on 25 March 1941).[105] Having been the first major city in Greece to fall to the occupying forces just two days after the German invasion, it was in Thessaloniki that the first Greek resistance group was formed (under the name Ελευθερία, Eleutheria, "Freedom")[106] as well as the first anti-Nazi newspaper in an occupied territory anywhere in Europe,[107] also by the name Eleutheria. Thessaloniki was also home to a military camp-converted-concentration camp, known in German as "Konzentrationslager Pavlo Mela" (Pavlos Melas Concentration Camp),[108] where members of the resistance and other non-favourable people towards the German occupation from all over Greece[108] were held either to be killed or sent to concentration camps elsewhere in Europe.[108] In the 1946 monarchy referendum, the majority of the locals voted in favour of a republic, contrary to the rest of Greece.[109]

After the war, Thessaloniki was rebuilt with large-scale development of new infrastructure and industry throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Many of its architectural treasures still remain, adding value to the city as a tourist destination, while several early Christian and Byzantine monuments of Thessaloniki were added to the UNESCO World Heritage list in 1988.[110] In 1997, Thessaloniki was celebrated as the European Capital of Culture,[111] sponsoring events across the city and the region. Agency established to oversee the cultural activities of that year 1997 was still in existence by 2010.[112] In 2004 the city hosted a number of the football events as part of the 2004 Summer Olympics.[113]

Today, Thessaloniki has become one of the most important trade and business hubs in Southeastern Europe, with its port, the Port of Thessaloniki being one of the largest in the Aegean and facilitating trade throughout the Balkan hinterland.[7] On 26 October 2012 the city celebrated its centennial since its incorporation into Greece.[114] The city also forms one of the largest student centres in Southeastern Europe, is host to the largest student population in Greece and was the European Youth Capital in 2014.[10][115]

Geography

Geology

Thessaloniki lies on the northern fringe of the Thermaic Gulf on its eastern coast and is bound by Mount Chortiatis on its southeast. Its proximity to imposing mountain ranges, hills and fault lines, especially towards its southeast have historically made the city prone to geological changes.

Since medieval times, Thessaloniki was hit by strong earthquakes, notably in 1759, 1902, 1978 and 1995.[116] On 19–20 June 1978, the city suffered a series of powerful earthquakes, registering 5.5 and 6.5 on the Richter scale.[117][118] The tremors caused considerable damage to a number of buildings and ancient monuments,[117] but the city withstood the catastrophe without any major problems.[118] One apartment building in central Thessaloniki collapsed during the second earthquake, killing many, raising the final death toll to 51.[117][118]

Climate

Thessaloniki's climate is directly affected by the sea it is situated on.[119] The city lies in a transitional climatic zone, so its climate displays characteristics of several climates. According to the Köppen climate classification, it ias a humid subtropical climate (Cfa) that borders on a Mediterranean climate (Csa), as well as a semi-arid climate (BSk), observed on the periphery of the region. With annual average precipitation of 450 mm (17.7 inches) due to the Pindus rain shadow drying the westerly winds. However, the city has a summer precipitation between 20 to 30 mm (0.79 to 1.18 inches), which is prevents it being qualified as a Mediterranean climate (Csa), and increases gradually towards the north and west, turning humid subtropical.

Winters are relatively dry, with common morning frost. Snowfalls are sporadic, but οccur more or less every winter, but the snow cover does not last for more than a few days. Fog is common, with an average of 193 foggy days in a year.[120] During the coldest winters, temperatures can drop to −10 °C (14 °F).[120] The record minimum temperature in Thessaloniki was −14 °C (7 °F).[121] On average, Thessaloniki experiences frost (sub-zero temperature) 32 days a year.[120] The coldest month of the year in the city is January, with an average 24-hour temperature of 6 °C (43 °F).[122] Wind is also usual in the winter months, with December and January having an average wind speed of 26 km/h (16 mph).[120]

Thessaloniki's summers are hot with rather humid nights.[120] Maximum temperatures usually rise above 30 °C (86 °F),[120] but rarely go over 40 °C (104 °F);[120] the average number of days the temperature is above 32 °C (90 °F) is 32.[120] The maximum recorded temperature in the city was 42 °C (108 °F).[120][121] Rain seldom falls in summer, mainly during thunderstorms. In the summer months Thessaloniki also experiences strong heat waves.[123] The hottest month of the year in the city is July, with an average 24-hour temperature of 26 °C (79 °F).[122] The average wind speed for June and July in Thessaloniki is 20 kilometres per hour (12 mph).[120]

| Climate data for Thessaloniki | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 9.3 (48.7) |

10.9 (51.6) |

14.2 (57.6) |

19.0 (66.2) |

24.5 (76.1) |

29.2 (84.6) |

31.5 (88.7) |

31.1 (88) |

27.2 (81) |

21.2 (70.2) |

15.4 (59.7) |

11.0 (51.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

6.6 (43.9) |

9.4 (48.9) |

13.3 (55.9) |

18.3 (64.9) |

22.8 (73) |

25.1 (77.2) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.1 (70) |

16.0 (60.8) |

11.1 (52) |

7.0 (44.6) |

15.1 (59.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

2.2 (36) |

4.5 (40.1) |

7.5 (45.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.6 (65.5) |

18.3 (64.9) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

6.8 (44.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

9.7 (49.5) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.8 (1.449) |

38.0 (1.496) |

40.6 (1.598) |

37.5 (1.476) |

44.4 (1.748) |

29.6 (1.165) |

23.9 (0.941) |

20.4 (0.803) |

27.4 (1.079) |

40.8 (1.606) |

54.4 (2.142) |

54.9 (2.161) |

448.7 (17.664) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.8 | 11.3 | 12.4 | 11.2 | 10.7 | 7.5 | 5.9 | 4.7 | 5.9 | 8.7 | 11.5 | 12.5 | 114.1 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 98.7 | 102.6 | 147.2 | 202.6 | 252.7 | 296.4 | 325.7 | 295.8 | 229.9 | 165.5 | 117.8 | 102.6 | 2,337.5 |

| Source: World Meteorological Organization (UN),[124] NOAA[125] for data of sunshine hours | |||||||||||||

Government

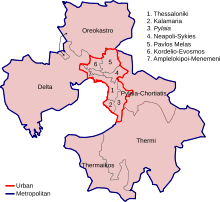

According to the Kallikratis reform, as of 1 January 2011 the Thessaloniki Urban Area (Greek: Πολεοδομικό Συγκρότημα Θεσσαλονίκης) which makes up the "City of Thessaloniki", is made up of six self-governing municipalities (Greek: Δήμοι) and one municipal unit (Greek: Δημοτική ενότητα). The municipalities that are included in the Thessaloniki Urban Area are those of Thessaloniki (the city center and largest in population size), Kalamaria, Neapoli-Sykies, Pavlos Melas, Kordelio-Evosmos, Ampelokipoi-Menemeni, and the municipal unit of Pylaia, part of the municipality of Pylaia-Chortiatis. Prior to the Kallikratis reform, the Thessaloniki Urban Area was made up of twice as many municipalities, considerably smaller in size, which created bureaucratic problems.[126]

Thessaloniki Municipality

The municipality of Thessaloniki (Greek: Δήμος Θεσαλονίκης) is the second most populous in Greece, after Athens, with a resident population of 325,182[127] (in 2011) and an area of 19.307 square kilometres (7.454 square miles), includes the municipal unit of Triandria. The municipality forms the core of the Thessaloniki Urban Area, with its central district (the city center), referred to as the Kentro, meaning 'center' or 'downtown'.

The institution of mayor of Thessaloniki was inaugurated under the Ottoman Empire, in 1912. The first mayor of Thessaloniki was Osman Sait Bey, while the current mayor of the municipality of Thessaloniki is Yiannis Boutaris. In 2011, the municipality of Thessaloniki had a budget of €464.33 million[128] while the budget of 2012 stands at €409.00 million.[129]

According to an article in The New York Times, the way in which the present mayor of Thessaloniki is treating the city's debt and oversized administration problems could be used as an example by Greece's central government for a successful strategy in dealing with these problems.[130]

Other

Thessaloniki is the second largest city in Greece. It is an influential city for the northern parts of the country and is the capital of the region of Central Macedonia and the Thessaloniki regional unit. The Ministry of Macedonia and Thrace is also based in Thessaloniki, being that the city is the de facto capital of the Greek region of Macedonia.

It is customary every year for the Prime Minister of Greece to announce his administration's policies on a number of issues, such as the economy, at the opening night of the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair. In 2010, during the first months of the 2010 Greek debt crisis, the entire cabinet of Greece met in Thessaloniki to discuss the country's future.[131]

In the Hellenic Parliament, the Thessaloniki urban area constitutes a 16-seat constituency. As of the national elections of 20 September 2015 the largest party in Thessaloniki is the Coalition of the Radical Left with 35.8% of the vote, followed by New Democracy (25.3%) and Golden Dawn (7.3%).[132] The table below summarizes the results of the latest elections.

| Party | Votes | % | Shift | Members of Parliament (16) | Change | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coalition of the Radical Left | 108,293 | 35.82% | 6 | ||||||||||||||||||

| New Democracy | 76,454 | 25.29% | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Golden Dawn | 21,969 | 7.27% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Union of Centrists | 20,483 | 6.77% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Communist Party of Greece | 16,046 | 5.31% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| The River (To Potami) | 14,641 | 4.84% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| PASOK—Democratic Left | 13,049 | 4.32% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Independent Greeks | 11,665 | 3.86% | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Other parties (unrepresented) | 19,575 | 6.53% | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||

Cityscape

Architecture

Architecture in Thessaloniki is the direct result of the city's position at the centre of all historical developments in the Balkans. Aside from its commercial importance, Thessaloniki was also for many centuries the military and administrative hub of the region, and beyond this the transportation link between Europe and the Levant (Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine). Merchants, traders and refugees from all over Europe settled in the city. The need for commercial and public buildings in this new era of prosperity led to the construction of large edifices in the city center. During this time, the city saw the building of banks, large hotels, theatres, warehouses, and factories. Architects who designed some of the most notable buildings of the city, in the late 19th and early 20th century, include Vitaliano Poselli, Pietro Arrigoni, Xenophon Paionidis, Eli Modiano, Moshé Jacques, Jean Joseph Pleyber, Frederic Charnot, Ernst Ziller, Roubens Max, Levi Ernst, Angelos Siagas and others, using mainly the styles of Eclecticism and Art Nouveau.

The city layout changed after 1870, when the seaside fortifications gave way to extensive piers, and many of the oldest walls of the city were demolished, including those surrounding the White Tower, which today stands as the main landmark of the city. As parts of the early Byzantine walls were demolished, this allowed the city to expand east and west along the coast.[134]

The expansion of Eleftherias Square towards the sea completed the new commercial hub of the city and at the time was considered one of the most vibrant squares of the city. As the city grew, workers moved to the western districts, because of their proximity to factories and industrial activities; while the middle and upper classes gradually moved from the city-center to the eastern suburbs, leaving mainly businesses. In 1917, a devastating fire swept through the city and burned uncontrollably for 32 hours.[73] It destroyed the city's historic center and a large part of its architectural heritage, but paved the way for modern development and allowed Thessaloniki the development of a proper European city center, featuring wider diagonal avenues and monumental squares; which the city initially lacked – much of what was considered to be 'essential' in European architecture.[73][135]

City centre

After the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, a team of architects and urban planners including Thomas Mawson and Ernest Hebrard, a French architect, chose the Byzantine era as the basis of their (re)building designs for Thessaloniki's city centre. The new city plan included axes, diagonal streets and monumental squares, with a street grid that would channel traffic smoothly. The plan of 1917 included provisions for future population expansions and a street and road network that would be, and still is sufficient today.[73] It contained sites for public buildings and provided for the restoration of Byzantine churches and Ottoman mosques.

Today, the city center of Thessaloniki includes the features designed as part of the plan and forms the point in the city where most of the public buildings, historical sites, entertainment venues and stores are located. The center is characterized by its many historical buildings, arcades, laneways and distinct architectural styles such as Art Nouveau and Art Deco, which can be seen on many of its buildings.

Also called the historic centre, it is divided into several districts, of which include Ladadika (where many entertainment venues and tavernas are located), Kapani (were the city's central city market is located), Diagonios, Navarinou, Rotonta, Agia Sofia and Ippodromio, which are all located around Thessaloniki's most central point, Aristotelous Square.

The west point of the city centre is home to Thessaloniki's law courts, its central international railway station and the port, while on its eastern side stands the city's two universities, the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Centre, the city's main stadium, its archaeological and Byzantine museums, the new city hall and its central parklands and gardens, namely those of the ΧΑΝΘ/Palios Zoologikos Kipos and Pedio tou Areos. The central road arteries that pass through the city centre, designed in the Ernest Hebrard plan, include those of Tsimiski, Egnatia, Nikis, Mitropoleos, Venizelou and St Demetrius avenues.

Ano Poli

Ano Poli (also called Old Town and literally the Upper Town) is the heritage listed district north of Thessaloniki's city center that was not engulfed by the great fire of 1917 and was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site by ministerial actions of Melina Merkouri, during the 1980s. It consists of Thessaloniki's most traditional part of the city, still featuring small stone paved streets, old squares and homes featuring old Greek and Ottoman architecture.

Ano Poli also, is the highest point in Thessaloniki and as such, is the location of the city's acropolis, its Byzantine fort, the Heptapyrgion, a large portion of the city's remaining walls, and with many of its additional Ottoman and Byzantine structures still standing. The area provides access to the Seich Sou Forest National Park[136] and features panoramic views of the whole city and the Thermaic Gulf. On clear days Mount Olympus, at about 100 km (62 mi) away across the gulf, can also be seen towering the horizon.

Southeastern Thessaloniki

Southeastern Thessaloniki up until the 1920s was home to the city's most affluent residents and formed the outermost suburbs of the city at the time, with the area close to the Thermaic Gulf coast called Exoches, from the 19th century holiday villas which defined the area. Today southeastern Thessaloniki has in some way become a natural extension of the city center, with the avenues of Megalou Alexandrou, Georgiou Papandreou (Antheon), Vasilissis Olgas, Delfon, Konstantinou Karamanli (Nea Egnatia) and Papanastasiou passing through it, enclosing an area traditionally called Dépôt (Ντεπώ), from the name of the old tram station, owned by a French company. The area extends to Kalamaria and Pylaia, about 9 km (5.59 mi) from the White Tower in the city center.

Some of the most notable mansions and villas of the old-era of the city remain along Vasilissis Olgas Avenue. Built for the most wealthy residents and designed by well known architects they are used today as museums, art galleries or remain as private properties. Some of them include Villa Bianca, Villa Ahmet Kapanci, Villa Modiano, Villa Mordoch, Villa Mehmet Kapanci, Hatzilazarou Mansion, Château Mon Bonheur (often called red tower) and others.

Most of southeastern Thessaloniki is characterized by its modern architecture and apartment buildings, home to the middle-class and more than half of the municipality of Thessaloniki population. Today this area of the city is also home to 3 of the city's main football stadiums, the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, the Posidonio aquatic and athletic complex, the Naval Command post of Northern Greece and the old royal palace (called Palataki), located on the most westerly point of Karabournaki cape. The municipality of Kalamaria is also located in southeastern Thessaloniki and has become this part of the city's most sought after areas, with many open spaces and home to high end bars, cafés and entertainment venues, most notably on Plastira street, along the coast.

Northwestern Thessaloniki

Northwestern Thessaloniki had always been associated with industry and the working class because as the city grew during the 1920s, many workers had moved there, because of its proximity near factories and industrial activities. Today many factories and industries have been moved further out west and the area is experiencing rapid growth as does the southeast. Many factories in this area have been converted to cultural centres, while past military grounds that are being surrounded by densely built neighborhoods are awaiting transformation into parklands.

Northwest Thessaloniki forms the main entry point into the city of Thessaloniki with the avenues of Monastiriou, Lagkada and 26is Octovriou passing through it, as well as the extension of the A1 motorway, feeding into Thessaloniki's city center. The area is home to the Macedonia InterCity Bus Terminal (KTEL), the Zeitenlik Allied memorial military cemetery and to large entertainment venues of the city, such as Milos, Fix, Vilka (which are housed in converted old factories). Northwestern Thessaloniki is also home to Moni Lazariston, located in Stavroupoli, which today forms one of the most important cultural centers for the city.[137]

Paleochristian and Byzantine monuments (UNESCO)

Because of Thessaloniki's importance during the early Christian and Byzantine periods, the city is host to several paleochristian monuments that have significantly contributed to the development of Byzantine art and architecture throughout the Byzantine Empire as well as Serbia.[110] The evolution of Imperial Byzantine architecture and the prosperity of Thessaloniki go hand in hand, especially during the first years of the Empire,[110] when the city continued to flourish. It was at that time that the Complex of Roman emperor Galerius was built, as well as the first church of Hagios Demetrios.[110]

By the 8th century, the city had become an important administrative center of the Byzantine Empire, and handled much of the Empire's Balkan affairs.[138] During that time, the city saw the creation of more notable Christian churches that are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites, such as Hagia Sophia of Thessaloniki, the Church of the Acheiropoietos, the Church of Panagia Chalkeon.[110] When the Ottoman Empire took control of Thessaloniki in 1430, most of the city's churches were converted into mosques,[110] but have survived to this day. Travelers such as Paul Lucas and Abdul Mecid[110] document the city's wealth in Christian monuments during the years of the Ottoman control of the city.

The church of Hagios Demetrios was burnt down during the Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917, as did many other of the city's monuments, but it was rebuilt. During World War II , the city was extensively bombed and as such many of Thessaloniki's paleochristian and Byzantine monuments were heavily damaged.[138] Some of the sites were not restored until the 1980s. Thessaloniki has more UNESCO World Heritage Sites listed than any other city in Greece, a total of 15 monuments.[110] They have been listed since 1988.[110]

Thessaloniki 2012 Program

With the 100th anniversary of the 1912 incorporation of Thessaloniki into Greece, the government announced a large-scale redevelopment program for the city of Thessaloniki, which aims in addressing the current environmental and spatial problems[139] that the city faces. More specifically, the program will drastically change the physiognomy of the city[139] by relocating the Thessaloniki International Exhibition Center and grounds of the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair outside the city centre and turning the current location into a large metropolitan park,[140] redeveloping the coastal front of the city,[140] relocating the city's numerous military camps and using the grounds and facilities to create large parklands and cultural centers;[140] and the complete redevelopment of the harbor and the Lachanokipoi and Dendropotamos districts (behind and near the Port of Thessaloniki) into a commercial business district,[140] with possible highrise developments.[141]

The plan also envisions the creation of new wide avenues in the outskirts of the city[140] and the creation of pedestrian-only zones in the city centre.[140] Furthermore, the program includes plans to expand the jurisdiction of Seich Sou Forest National Park[139] and the improvement of accessibility to and from the Old Town.[139] The ministry has said that the project will take an estimated 15 years to be completed, in 2025.[140]

Part of the plan has been implemented with extensive pedestrianization's within the city center by the municipality of Thessaloniki and the revitalization the eastern urban waterfront/promenade, Nea Paralia (Greek: Νέα Παραλία, literally new beach), with a modern and vibrant design. Its first section opened in 2008, having been awarded as the best public project in Greece of the last five years by the Hellenic Institute of Architecture.[142]

The municipality of Thessaloniki's budget for the reconstruction of important areas of the city and the completion of the waterfront, opened in January 2014, was estimated at around €28.2 million (US$39.9 million) for the year 2011 alone.[143]

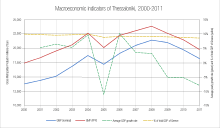

Economy

GDP of the Thessaloniki regional unit 2000–2011 | |

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| GDP | €19.851 billion (PPP, 2011)[2] |

| GDP rank | 2nd in Greece |

GDP growth | -7.8% (2011)[2] |

GDP per capita | €17,200 (PPP, 2011)[2] |

Labour force | 534,800 (2010)[144] |

| Unemployment | 30.2% (2014)[145] |

Thessaloniki rose to economic prominence as a major economic hub in the Balkans during the years of the Roman Empire. The Pax Romana and the city's strategic position allowed for the facilitation of trade between Rome and Byzantium (later Constantinople and now Istanbul) through Thessaloniki by means of the Via Egnatia.[146] The Via Egnatia also functioned as an important line of communication between the Roman Empire and the nations of Asia,[146] particularly in relation to the Silk Road. With the partition of the Roman Emp. into East (Byzantine) and West, Thessaloniki became the second-largest city of the Eastern Roman Empire after New Rome (Constantinople) in terms of economic might.[33][146] Under the Empire, Thessaloniki was the largest port in the Balkans.[147] As the city passed from Byzantium to the Republic of Venice in 1423, it was subsequently conquered by the Ottoman Empire. Under Ottoman rule the city retained its position as the most important trading hub in the Balkans.[64] Manufacturing, shipping and trade were the most important components of the city's economy during the Ottoman period,[64] and the majority of the city's trade at the time was controlled by ethnic Greeks.[64]

Historically important industries for the economy of Thessaloniki included tobacco (in 1946 35% of all tobacco companies in Greece were headquartered in the city, and 44% in 1979)[148] and banking (in Ottoman years Thessaloniki was a major center for investment from western Europe, with the Bank of Thessaloniki (French: Banque de Salonique) having a capital of 20 million French francs in 1909).[64]

Services

The service sector accounts for nearly two thirds of the total labour force of Thessaloniki.[149] Of those working in services, 20% were employed in trade, 13% in education and healthcare, 7.1% in real estate, 6.3% in transport, communications & storing, 6.1% in the finance industry & service-providing organizations, 5.7% in public administration & insurance services and 5.4% in hotels & restaurants.[149]

The city's port, the Port of Thessaloniki, is one of the largest ports in the Aegean and as a free port, it functions as a major gateway to the Balkan hinterland.[7][150] In 2010, more than 15.8 million tons of products went through the city's port,[151] making it the second-largest port in Greece after Aghioi Theodoroi, surpassing Piraeus. At 273,282 TEUs, it is also Greece's second-largest container port after Piraeus.[152] As a result, the city is a major transportation hub for the whole of south-eastern Europe,[153] carrying, among other things, trade to and from the neighbouring countries.

In recent years Thessaloniki has begun to turn into a major port for cruising in the eastern Mediterranean.[150] The Greek ministry of tourism considers Thessaloniki to be Greece's second most important commercial port,[154] and companies such as Royal Caribbean International have expressed interest in adding the Port of Thessaloniki to their destinations.[154] A total of 30 cruise ships are expected to arrive at Thessaloniki in 2011.[154]

In recent years a spate of factory shut downs has occurred as companies take advantage of cheaper labour markets and more lax regulations in other areas. Among the largest companies to shut down factories are Goodyear,[155] AVEZ (the first industrial factory in northern Greece, built in 1926),[156] and VIAMIL (ΒΙΑΜΥΛ). Nevertheless, Thessaloniki still remains a major business hub in the Balkans, with a number of important Greek companies headquartered in the city, such as the Hellenic Vehicle Industry, the Macedonian Milk Industry, Philkeram Johnson and MLS Multimedia, which introduced the first Greek-built smartphone in 2012.[157]

Macroeconomic indicators

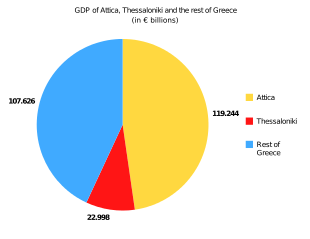

In 2011, the regional unit of Thessaloniki had a Gross Domestic Product of €18.293 billion (ranked 2nd amongst the country's regional units),[2] comparable to Bahrain or Cyprus, and a per capita of €15,900 (ranked 16th).[2] In Purchasing Power Parity, the same indicators are €19,851 billion (2nd)[2] and €17,200 (15th) respectively.[2] In terms of comparison with the European Union average, Thessaloniki's GDP per capita indicator stands at 63% the EU average[2] and 69% in PPP[2] – this is comparable to the German state of Brandenburg.[2] Overall, Thessaloniki accounts for 8.9% of the total economy of Greece.[2] Between 1995 and 2008 Thessaloniki's GDP saw an average growth rate of 4.1% per annum (ranging from +14.5% in 1996 to -11.1% in 2005) while in 2011 the economy contracted by -7.8%.[2]

Demographics

Historical ethnic statistics

The tables below show the ethnic statistics of Thessaloniki during the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century.

| Year | Total Population | Jewish | Turkish (Muslim) | Greek | Bulgarian | Roma | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1890[158] | 118,000 | 55,000 | 26,000 | 16,000 | 10,000 | 2,500 | 8,500 |

| around 1913[159] | 157,889 | 61,439 | 45,889 | 39,956 | 6,263 | 2,721 | 1,621 |

Population growth

| Population | |

|---|---|

| Year | Pop. |

| 1348 | 150,000 |

| 1453 | 40,000 |

| 1679 | 36,000 |

| 1842 | 70,000 |

| 1870 | 90,000 |

| 1882 | 85,000 |

| 1890 | 118,000 |

| 1902 | 126,000 |

| 1913 | 157,000 |

| 1917 | 230,000 |

| 1951 | 297,164 |

| 1961 | 377,026 |

| 1981 | 406,413 |

| 1991 | 383,967 |

| 2001 | 786,212 |

| 2011 | 788,952 |

| From 2001 on, data on the city's urban area. References:[39][73][127][160][161][162] | |

The municipality of Thessaloniki is the most populated municipality of all the municipalities that are part of the Thessaloniki Urban Area and make up the "City of Thessaloniki". Although the population of the municipality of Thessaloniki has declined in the latest census, the metropolitan area's population is still growing. The city forms the base of the Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area, with latest census in 2011 giving it a population of 1,104,460.[127]

| Year | Municipality | Urban area | Metropolitan area | rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 363,987[162] | 786,212[162] | 954,027[162] | |

| 2004 | 386,627[163] | – | 995,766[163] | |

| 2011 | 325,182 | 788,952[127] | 1,104,460[127] |

Jews of Thessaloniki

The Jewish population in Greece is the oldest in mainland Europe (see Romaniotes). When Paul the Apostle came in Thessaloniki he taught in the area of what today is called Upper City. Later, during the Ottoman period, with the coming of Sephardic Jews from Spain, the community of Thessaloniki became mostly Sephardic. Thessaloniki became the largest center in Europe of the Sephardic Jews, who nicknamed the city la madre de Israel (Israel's mother)[101] and "Jerusalem of the Balkans".[164] It also included the historically significant and ancient Greek-speaking Romaniote community. During the Ottoman era, Thessaloniki's Sephardic community comprised more than half the city's population; Jewish merchants were prominent in commerce until the ethnic Greek population increased after independence in 1912. By the 1680s, about 300 families of Sephardic Jews, followers of Sabbatai Zevi, had converted to Islam, becoming a sect known as the Dönmeh (convert), and migrated to Salonika, whose population was majority Jewish. They established an active community that thrived for about 250 years. Many of their descendants later became prominent in trade.[165] Many Jewish inhabitants of Thessaloniki spoke Ladino, the Romance language of the Sephardic Jews.[166]

From the second half of the 19th century with the Ottoman reforms, the Jewish community had a new revival. Many French and especially Italian Jews (from Livorno and other cities), influential in introducing new methods of education and developing new schools and intellectual environment for the Jewish population, were established in Thessaloniki. Such modernists introduced also new techniques and ideas from the industrialized Western Europe and from the 1880s the city began to industrialize. The Italian Jews Allatini brothers led Jewish entrepreneurship, establishing milling and other food industries, brickmaking and processing plants for tobacco. Several traders supported the introduction of a large textile-production industry, superseding the weaving of cloth in a system of artisanal production. Other notable names of the era include the Italian Jewish Modiano family and the Italians Poselli. With industrialization, many people of all faiths became factory workers, part of a new proletariat, which later led to the establishment of the Socialist Workers' Federation.

After the Balkan Wars, Thessaloniki was incorporated into the Greek Kingdom. At first the community feared that the annexation would lead to difficulties and during the first years its political stance was, in general, anti-Venizelist and pro-royalist/conservative. The Great Thessaloniki Fire of 1917 during World War I burned much of the center of the city and left 50,000 Jews homeless of the total of 72,000 residents who were burned out.[96] Having lost homes and their businesses, many Jews emigrated: to the United States, Palestine, and Paris. They could not wait for the government to create a new urban plan for rebuilding, which was eventually done.[167]

After the Greco-Turkish War in 1922 and the expulsion of Greeks from Turkey, many refugees came to Greece. Nearly 100,000 ethnic Greeks resettled in Thessaloniki, reducing the proportion of Jews in the total community. After this, Jews made up about 20% of the city's population. During the interwar period, Greece granted Jewish citizens the same civil rights as other Greek citizens.[96] In March 1926, Greece re-emphasized that all citizens of Greece enjoyed equal rights, and a considerable proportion of the city's Jews decided to stay. During the Metaxas regime the stance towards Jews became even better.

World War II brought a disaster for the Jewish Greeks, since in 1941 the Germans occupied Greece and began actions against the Jewish population. Greeks of the Resistance helped save some of the Jewish residents.[101] By the 1940s, the great majority of the Jewish Greek community firmly identified as both Greek and Jewish. According to Misha Glenny, such Greek Jews had largely not encountered "anti-Semitism as in its North European form."[168]

In 1943 the Nazis began brutal, inhumane actions against the historic Jewish population in Thessaloniki, forcing them into a ghetto near the railroad lines and beginning deportation to concentration and labor camps where they dehumanized their captives. They deported and exterminated approximately 96% of Thessaloniki's Jews of all ages during the Holocaust.[169] The Thessaloniki Holocaust memorial in Eleftherias ("Freedom") Square was built in 1997 in memory of all the Jewish people from Thessaloniki, who died in the Holocaust. The site was chosen because it was the place where Jews residents were rounded up before embarking to trains for concentration camps.[170][171] Today, a community of around 1200 remains in the city.[101] Communities of descendants of Thessaloniki Jews – both Sephardic and Romaniote – live in other areas, mainly the United States and Israel.[169] Israeli singer Yehuda Poliker recorded a song about the Jewish people of Thessaloniki, called "Wait for me, Thessaloniki". Not only did the Jewish-Greek population of Thessaloniki perish during the Holocaust, but a unique civilization filled with rich culture and beauty was lost.

| Year | Total population |

Jewish population |

Jewish percentage |

Source[96] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1842 | 70,000 | 36,000 | 51% | Jakob Philipp Fallmerayer |

| 1870 | 90,000 | 50,000 | 56% | Greek schoolbook (G.K. Moraitopoulos, 1882) |

| 1882/84 | 85,000 | 48,000 | 56% | Ottoman government census |

| 1902 | 126,000 | 62,000 | 49% | Ottoman government census |

| 1913 | 157,889 | 61,439 | 39% | Greek government census |

| 1917 | 271,157 | 52,000 | 19% | [172] |

| 1943 | 50,000 | |||

| 2000 | 363,987[162] | 1,000 | 0.27% |

Others

Since the late 19th century, many merchants from Western Europe (mainly from France and Italy) were established in the city. They had an important role in the social and economical life of the city and in many cases introduced new industrial techniques. Their main district was what is known today as the "Frankish district" (near Ladadika), where locates also the Catholic church designed by Vitaliano Poselli. Some of them left after the incorporation of the city into the Greek Kingdom, others, who were of Jewish faith, were exterminated by the Nazis, while others stayed and their descendants still live in the city.

Another group is the Armenian community which dates back to the Ottoman period. During the 20th century, after the Armenian Genocide and the defeat of the Greek army in the Greco-Turkish War (1919–22), many fled to Greece and a large part of them was established in Thessaloniki. There is also an Armenian church at the center of the city.

Culture

Leisure and entertainment

Thessaloniki is not only regarded as the cultural and entertainment capital of northern Greece[138][173] but also the cultural capital of the country.[8] The city's main theaters, run by the National Theatre of Northern Greece (Greek: Κρατικό Θέατρο Βορείου Ελλάδος) which was established in 1961,[174] include the Theater of the Society of Macedonian Studies, where the National Theater is based, the Royal Theater (Vasiliko Theatro) -the first base of the National Theater-, Moni Lazariston, and the Earth Theater and Forest Theater, both amphitheatrical open-air theatres overlooking the city.[174]

The title of the European Capital of Culture in 1997 saw the birth of the city's first opera[175] and today forms an independent section of the National Theatre of Northern Greece.[176] The opera is based at the Thessaloniki Concert Hall, one of the largest concert halls in Greece. Recently a second building was also constructed and designed by Japanese architect Arata Isozaki. Thessaloniki is also the seat of two symphony orchestras, the Thessaloniki State Symphony Orchestra and the Symphony Orchestra of the Municipality of Thessaloniki. Olympion Theater, the site of the Thessaloniki International Film Festival and the Plateia Assos Odeon multiplex are the two major cinemas in downtown Thessaloniki. The city also has a number of multiplex cinemas in major shopping malls in the suburbs, most notably in Mediterranean Cosmos, the largest retail and entertainment development in the Balkans.

Thessaloniki is renowned for its major shopping streets and lively laneways. Tsimiski Street and Proxenou Koromila avenue are the city's most famous shopping streets and are among Greece's most expensive and exclusive high streets. The city is also home to one of Greece's most famous and prestigious hotels, Makedonia Palace hotel, the Hyatt Regency Casino and hotel (the biggest casino in Greece and one of the biggest in Europe) and Waterland, the largest water park in southeastern Europe.

The city has long been known in Greece for its vibrant city culture, including having the most cafes and bars per capita of any city in Europe; and as having some of the best nightlife and entertainment in the country, thanks to its large young population and multicultural feel. Lonely Planet listed Thessaloniki among the world's "ultimate party cities".[177]

Parks and recreation

Although Thessaloniki is not renowned for its parks and greenery throughout its urban area, where green spaces are few, it has several large open spaces around its waterfront, namely the central city gardens of Palios Zoologikos Kipos (which is recently being redeveloped to also include rock climbing facilities, a new skatepark and paintball range),[178] the park of Pedio tou Areos, which also holds the city's annual floral expo; and the parks of the Nea Paralia (waterfront) that span for 3 km (2 mi) along the coast, from the White Tower to the concert hall.

The Nea Paralia parks are used throughout the year for a variety of events, while they open up to the Thessaloniki waterfront, which is lined up with several cafés and bars; and during summer is full of Thessalonians enjoying their long evening walks (referred to as "the volta" and is embedded into the culture of the city). Having undergone an extensive revitalization, the city's waterfront today features a total of 12 thematic gardens/parks.[179]

Thessaloniki's proximity to places such as the national parks of Pieria and beaches of Chalkidiki often allow its residents to easily have access to some of the best outdoor recreation in Europe; however, the city is also right next to the Seich Sou forest national park, just 3.5 km (2 mi) away from Thessaloniki's city center; and offers residents and visitors alike, quiet viewpoints towards the city, mountain bike trails and landscaped hiking paths.[180] The city's zoo, which is operated by the municipality of Thessaloniki, is also located nearby the national park.[181]

Other recreation spaces throughout the Thessaloniki Metropolitan Area include the Fragma Thermis, a landscaped parkland near Thermi and the Delta wetlands west of the city center; while urban beaches that have continuously been awarded the blue flags,[182] are located along the 10 km (6 mi) coastline of Thessaloniki's southeastern suburbs of Thermaikos, about 20 km (12 mi) away from the city center.

Museums and galleries

Because of the city's rich and diverse history, Thessaloniki houses many museums dealing with many different eras in history. Two of the city's most famous museums include the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of Byzantine Culture.

The Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki was established in 1962 and houses some of the most important ancient Macedonian artifacts,[183] including an extensive collection of golden artwork from the royal palaces of Aigai and Pella.[184] It also houses exhibits from Macedon's prehistoric past, dating from the Neolithic to the Bronze age.[185] The Prehistoric Antiquities Museum of Thessaloniki has exhibits from those periods as well.

The Museum of Byzantine Culture is one of the city's most famous museums, showcasing the city's glorious Byzantine past.[186] The museum was also awarded Council of Europe's museum prize in 2005.[187] The museum of the White Tower of Thessaloniki houses a series of galleries relating to the city's past, from the creation of the White Tower until recent years.[188]

One of the most modern museums in the city is the Thessaloniki Science Center and Technology Museum and is one of the most high-tech museums in Greece and southeastern Europe.[189] It features the largest planetarium in Greece, a cosmotheater with the largest flat screen in Greece, an amphitheater, a motion simulator with 3D projection and 6-axis movement and exhibition spaces.[189] Other industrial and technological museums in the city include the Railway Museum of Thessaloniki, which houses an original Orient Express train, the War Museum of Thessaloniki and others. The city also has a number of educational and sports museums, including the Thessaloniki Olympic Museum.

The Atatürk Museum in Thessaloniki is the historic house where Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, founder of modern-day Turkey, was born. The house is now part of the Turkish consulate complex, but admission to the museum is free.[190] The museum contains historic information about Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and his life, especially while he was in Thessaloniki.[190] Other ethnological museums of the sort include the Historical Museum of the Balkan Wars, the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki and the Museum of the Macedonian Struggle, containing information about the freedom fighters in Macedonia and their struggle to liberate the region from the Ottoman yoke.[191]

The city also has a number of important art galleries. Such include the Macedonian Museum of Contemporary Art, housing exhibitions from a number of well-known Greek and foreign artists.[192] The Teloglion Foundation of Art is part of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and includes an extensive collection of works by important artists of the 19th and 20th centuries, including works by prominent Greeks and native Thessalonians.[193] The Thessaloniki Museum of Photography also houses a number of important exhibitions, and is located within the old port of Thessaloniki.[194]

Archaeological sites

Thessaloniki is home to a number of prominent archaeological sites. Apart from its recognized UNESCO World Heritage Sites, Thessaloniki features a large two-terraced Roman forum[195] featuring two-storey stoas,[196] dug up by accident in the 1960s.[195] The forum complex also boasts two Roman baths,[197] one of which has been excavated while the other is buried underneath the city.[197] The forum also features a small theater,[195][197] which was also used for gladiatorial games.[196] Although the initial complex was not built in Roman times, it was largely refurbished in the 2nd century.[197] It is believed that the forum and the theater continued to be used until at least the 6th century.[198]

Another important archaeological site is the imperial palace complex which Roman emperor Galerius, located at Navarinou Square, commissioned when he made Thessaloniki the capital of his portion of the Roman Empire.[29][30] The large octagonal portion of the complex, most of which survives to this day, is believed to have been an imperial throne room.[196] Various mosaics from the palatial complex have also survived.[199] Some historians believe that the complex must have been in use as an imperial residence until the 11th century.[198]

Not far from the palace itself is the Arch of Galerius,[199] known colloquially as the Kamara. The arch was built to commemorate the emperor's campaigns against the Persians.[196][199] The original structure featured three arches;[196] however, only two full arches and part of the third survive to this day. Many of the arches' marble parts survive as well,[196] although it is mostly the brick interior that can be seen today.

Other monuments of the city's past, such as the Incantadas, a Caryatid portico from the ancient forum, have been removed or destroyed over the years. The Incantadas in particular are on display at the Louvre.[195][200] Thanks to a private donation of €180,000, it was announced on 6 December 2011 that a replica of the Incantadas would be commissioned and later put on display in Thessaloniki.[200]

Festivals

Thessaloniki is home of a number of festivals and events.[201] The Thessaloniki International Trade Fair is the most important event to be hosted in the city annually, by means of economic development. It was first established in 1926[202] and takes place every year at the 180,000 m2 (1,937,503.88 sq ft) Thessaloniki International Exhibition Center. The event attracts major political attention and it is customary for the Prime Minister of Greece to outline his administration's policies for the next year, during event. Over 250,000 visitors attended the exposition in 2010.[203] The new Art Thessaloniki, is starting first time 29.10. - 1 November 2015 as an international contemporary art fair. The Thessaloniki International Film Festival is established as one of the most important film festivals in Southern Europe,[204] with a number of notable film makers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Faye Dunaway, Catherine Deneuve, Irene Papas and Fatih Akın taking part, and was established in 1960.[205] The Documentary Festival, founded in 1999, has focused on documentaries that explore global social and cultural developments, with many of the films presented being candidates for FIPRESCI and Audience Awards.[206]

The Dimitria festival, founded in 1966 and named after the city's patron saint of St. Demetrius, has focused on a wide range of events including music, theatre, dance, local happenings, and exhibitions.[207] The "DMC DJ Championship" has been hosted at the International Trade Fair of Thessaloniki, has become a worldwide event for aspiring DJs and turntablists. The "International Festival of Photography" has taken place every February to mid-April.[208] Exhibitions for the event are sited in museums, heritage landmarks, galleries, bookshops and cafés. Thessaloniki also holds an annual International Book Fair.[209]

Between 1962–1997 and 2005–2008 the city also hosted the Thessaloniki Song Festival,[210] Greece's most important music festival, at Alexandreio Melathron.[211]

In 2012, the city hosted its first gay parade, namely the Thessaloniki Pride which took place between 22 and 23 June.[212] In 2013, the second Thessaloniki Pride was hosted between 14 and 15 June.[213] However, in 2013, Transgender people in Thessaloniki became victims of police violence. The issue was soon settled by the government.[214] The third Thessaloniki Pride took place in 2014, between 20 and 21 June, concentrating more people than any past year.[215]

Sports

The main stadium of the city is the Kaftanzoglio Stadium (also home ground of Iraklis FC), while other main stadiums of the city include the football Kleanthis Vikelidis Stadium and Toumba Stadium home grounds of Aris F.C. and PAOK F.C., respectively, all of whom are founding members of the Greek league.

Being the largest "multi-sport" stadium in the city, Kaftanzoglio Stadium regularly plays host to athletics events; such as the European Athletics Association event "Olympic Meeting Thessaloniki" every year; it has hosted the Greek national championships in 2009 and has been used for athletics at the Mediterranean Games and for the European Cup in athletics. In 2004 the stadium served as an official Athens 2004 venue,[216] while in 2009 the city and the stadium hosted the 2009 IAAF World Athletics Final.

Thessaloniki's major indoor arenas include the state-owned Alexandreio Melathron, PAOK Sports Arena and the YMCA indoor hall. Other sporting clubs in the city include Apollon FC based in Kalamaria, Agrotikos Asteras F.C. based in Evosmos and YMCA. Thessaloniki has a rich sporting history with its teams winning the first ever panhellenic football,[217] basketball,[218] and water polo[219] tournaments.

The city played a major role in the development of basketball in Greece. The local YMCA was the first to introduce the sport to the country, while Iraklis BC won the first ever Greek championship.[218] From 1982 to 1993 Aris BC dominated the league, regularly finishing in first place. In that period Aris won a total of 9 championships, 7 cups and one European Cup Winners' Cup. The city also hosted the 2003 FIBA Under-19 World Championship in which Greece came third. In volleyball, Iraklis has emerged since 2000 as one of the most successful teams in Greece[220] and Europe - see 2005–06 CEV Champions League.[221] In October 2007, Thessaloniki also played host to the first Southeastern European Games.[222]

The city is also the finish point of the annual Alexander The Great Marathon, which starts at Pella, in recognition of its Ancient Macedonian heritage.[223]

| Club | Founded | Venue | Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Iraklis | 1908 | Kaftanzoglio National Stadium |

27,770 |

| Maccabi Thessaloniki | 1908 | ||

| Aris | 1914 | Kleanthis Vikelidis Stadium | 22,800 |

| Alexandreio Melathron (Palais des Sports) | 5,500 | ||

| YMCA Thessaloniki (ΧΑΝΘ) | 1921 | ||

| Megas Alexandros | 1923 | ||

| PAOK | 1926 | Toumba Stadium | 28,703 |

| PAOK Sports Arena | 10,000 | ||

| Apollon | 1926 | Kalamaria Stadium | 6,500 |

| MENT | 1926 | ||

| VAO | 1926 | ||

| Makedonikos | 1928 | Makedonikos Stadium | 8,100 |

| Agrotikos Asteras | 1932 | Evosmos Stadium |

Media

Thessaloniki is home to the ERT3 TV-channel and Radio Macedonia, both services of Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation (ERT) operating in the city and are broadcast all over Greece.[224] The municipality of Thessaloniki also operates three radio stations, namely FM100, FM101 and FM100.6;[225] and TV100, a television network which was also the first non-state-owned TV station in Greece and opened in 1988.[225] Several private TV-networks also broadcast out from Thessaloniki, with Makedonia TV being the most popular.

The city's main newspapers and some of the most circulated in Greece, include Makedonia, which was also the first newspaper published in Thessaloniki in 1911 and Aggelioforos. A large number of radio stations also broadcast from Thessaloniki as the city is known for its music contributions.

Notable Thessalonians

Throughout its history, Thessaloniki has been home to a number of well-known figures like Nikolaos Polychronakos. It is also the birthplace of various Saints and other religious figures, such as Cyril and Methodius, creators of the first Slavic alphabet, Saint Mitre, Patriarch Philotheus I of Constantinople and Archbishop Demetrios of America. Many of Greece's most celebrated musicians and movie stars were born in Thessaloniki, such as Zoe Laskari, Costas Hajihristos, Antonis Remos, Paschalis Terzis, Natassa Theodoridou, Katia Zygouli, Kostas Voutsas, Marios Iliopoulos and Marinella. Additionally, there have been a number of political leaders born in the city Evangelos Venizelos, the former Minister of Finance of Greece, Haris Kastanidis, Christos Sartzetakis, fourth President of Greece, Kostas Zouraris and Ioannis Passalidis. Sports personalities from the city include Angelos Charisteas, Eleni Daniilidou, Dimitris Salpingidis, Traianos Dellas, Kleanthis Vikelidis and Ioannis Tamouridis. Ioannis Papafis and Elias Petropoulos were also born in Thessaloniki.

The city is also the birthplace of a number of important international personalities, which include Bulgarians (Atanas Dalchev), Jews (Moshe Levy, Daniel Zion, Samuel ben Joseph Uziel, Shlomo Halevi Alkabetz), Slav Macedonians (Dimo Todorovski) and Turks (Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, Nâzım Hikmet, Afet İnan, Cahit Arf, Mehmet Cavit Bey, Salih Omurtak, Sabiha Sertel, Halil Rifat Pasha).

Cuisine

Because Thessaloniki remained under Ottoman rule for about 100 years more than southern Greece, it has retained a lot of its Eastern character, including its culinary tastes.[226] Spices in particular play an important role in the cuisine of Thessaloniki,[226] something which is not true to the same degree about Greece's southern regions.[226] Thessaloniki's Ladadika borough is a particularly busy area in regards to Thessalonian cuisine, with most tavernas serving traditional meze and other such culinary delights.[226]

Bougatsa, a breakfast pastry, is very popular throughout the city and has spread around other parts of Greece and the Balkans as well. Another popular snack is koulouri.

Notable sweets of the city are Trigona, Roxakia and Armenovil. A stereotypical Thessalonian coffee drink is Frappé coffee. Frappé was invented in the Thessaloniki International Trade Fair in 1957 and has since spread throughout Greece and Cyprus to become a hallmark of the Greek coffee culture.

Music

The city is viewed as a romantic one in Greece, and as such Thessaloniki is commonly featured in Greek songs.[227] There are a number of famous songs that go by the name 'Thessaloniki' (rebetiko, laïko etc.) or include the name in their title.[228]

During the 1930s and 40s the city became a center of the Rebetiko music, partly because of the Metaxas censorship, which was stricter in Athens. Vassilis Tsitsanis wrote some of his best songs in Thessaloniki.

The city is the birthplace of significant composers in the Greek music scene, such as Manolis Chiotis, Stavros Kouyioumtzis and Dionysis Savvopoulos. It is also notable for its rock music scene and its many rock groups; some became famous such as Xylina Spathia, Trypes or the pop rock Onirama.

Between 1962–1997 and 2005–2008 the city also hosted the Thessaloniki Song Festival. In the Eurovision Song Contest 2013 Greece was represented by Koza Mostra and Agathonas Iakovidis, both from Thessaloniki.

In popular culture

- On May 1936, a massive strike by tobacco workers led to general anarchy in the city and Ioannis Metaxas (future dictator, then PM) ordered its repression. The events and the deaths of the protesters inspired Yiannis Ritsos to write the Epitafios.

- On 22 May 1963, Grigoris Lambrakis, pacifist and MP, was assassinated by two far-right extremists driving a three-wheeled vehicle. The event led to political crisis. Costa Gavras directed Z (1969 film) based on it, two years after the military junta had ceized power in Greece.

- Notable films set in Thessaloniki among others include Mademoiselle Docteur (1937) by Georg Wilhelm Pabst, The Barefooted Battalion (1954) by Greg Tallas (Gregory Thalassinos), O Atsidas (1961) by Giannis Dalianidis, Parenthesis (1968) by Takis Kanellopoulos and Triumph of the Spirit (1989) by Robert M. Young.

Education

Thessaloniki is a major center of education for Greece. Two of the country's largest universities are located in central Thessaloniki: Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and the University of Macedonia. Aristotle University was founded in 1926 and is currently the largest university in Greece[11] by number of students, which number at more than 80,000 in 2010,[11] and is a member of the Utrecht Network. For the academic year 2009–2010, Aristotle University was ranked as one of the 150 best universities in the world for arts and humanities and among the 250 best universities in the world overall by the Times QS World University Rankings,[229] making it one of the top 2% of best universities worldwide.[230] Leiden ranks Aristotle University as one of the top 100 European universities and the best university in Greece, at number 97.[231] Since 2010, Thessaloniki is also home to the Open University of Thessaloniki,[232] which is funded by Aristotle University, the University of Macedonia and the municipality of Thessaloniki.