Varna

| Varna Варна (Bulgarian) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

From top left: Asparuhov most, Black Sea beach, Euxinograd, Varna Archaeological Museum, Stoyan Bachvarov Dramatic Theatre, Dormition of the Mother of God Cathedral, Drazki torpedo boat, Navy Club, Palace of Sports and Culture, Ancient Roman baths, Varna Ethnographic Museum | |||

| |||

|

Nickname(s): Marine (or summer) capital of Bulgaria Морска (лятна) столица на България (Bulgarian) Morska (lyatna) stolitsa na Balgariya (transliteration) | |||

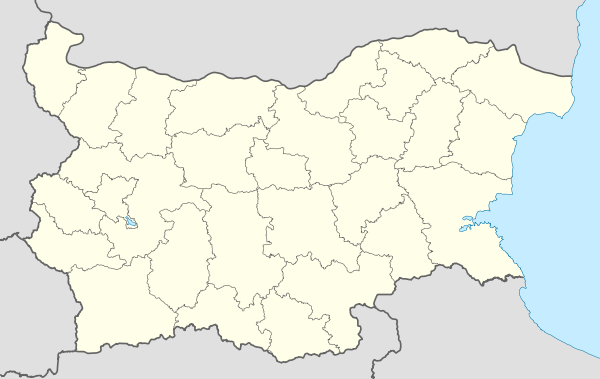

Location of Varna in Bulgaria | |||

| Coordinates: 43°13′N 27°55′E / 43.217°N 27.917°ECoordinates: 43°13′N 27°55′E / 43.217°N 27.917°E | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Province | Varna | ||

| Municipality | Varna | ||

| Established | 575 BCE | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Ivan Portnih | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 154.236 km2 (59.551 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 80 m (260 ft) | ||

| Population (03-15-2016)[1] | |||

| • Total |

| ||

| • Urban |

| ||

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) | ||

| Postcode | 9000 | ||

| Area code(s) | +359 52 | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Varna (Bulgarian: Варна, pronounced [ˈvarnɐ]) is the largest city and seaside resort on the Bulgarian Black Sea Coast, with a population of 334,466 inhabitants as of 2015, while 417,867 live in its functional urban area.

Varna is a major tourist destination, a business and university centre, seaport, and headquarters of the Bulgarian Navy and merchant marine. In 2008, Varna was designated seat of the Black Sea Euro-Region by the Council of Europe.[3]

The oldest gold jewelry in the world, belonging to the Varna culture, was discovered in the Varna Necropolis and dates to 4200-4600 BC.[4]

Etymology

Theophanes the Confessor first mentioned the name Varna, as the city came to be known with the Slavic conquest of the Balkans in the 6th–7th century. The name could be of Varangian origin, as Varangians had been crossing the Black Sea for many years, reaching Constantinople in the early Middle Ages. In Swedish, the meaning of 'värn' is 'shield', 'defense' - hence Varna is a defended, fortified place.[5] The name may be older than that; perhaps it derives from Proto-Indo-European root we-r- (water)[6] (see also Varuna), or from Proto-Slavic root varn (black), or from Iranian bar or var (camp, fortress: see also Etymological list of provinces of Bulgaria). According to Theophanes, in 680 Asparukh, the founder of the First Bulgarian Empire, routed an army of Constantine IV near the Danube delta and, pursuing it, reached the so-called Varna near Odyssos [sic] (τὴν λεγομένην Βάρναν, πλησίον Ὀδυσσοῦ) and the midlands thereof. Perhaps the new name applied initially to an adjacent river or lake, a Roman military camp, or an inland area, and only later to the city itself. By the late 10th century, the name Varna was established so firmly that when Byzantines wrestled back control of the area from the Bulgarians in the 970's, they kept it rather than restoring the ancient name Odessos. The latter is often said to be of Carian origin, though no modern scholarship supports this.

Geography and transportation

The city occupies 238 km2 (92 sq mi)[7] on verdant terraces (Varna monocline of the Moesian platform) descending from the calcareous Franga Plateau (height 356 m or 1,168 ft) on the north and Avren Plateau on the south, along the horseshoe-shaped Varna Bay of the Black Sea, the elongated Lake Varna, and two artificial waterways connecting the bay and the lake and bridged by the Asparuhov most. It is the centre of a growing conurbation stretching along the seaboard 20 km (12 mi) north and 10 km (6 mi) south (mostly residential and recreational sprawl) and along the lake 25 km (16 mi) west (mostly transportation and industrial facilities). Since antiquity, the city has been surrounded by vineyards, orchards, and forests. Commercial shipping facilities are being relocated inland into the lakes and canals, while the bay remains a recreation area; almost all the waterfront is parkland.

The urban area has in excess of 20 km (12 mi) of sand beaches and abounds in thermal mineral water sources (temperature 35–55 °C or 95–131 °F). It enjoys a mild climate influenced by the sea with long, mild, akin to Mediterranean, autumns, and sunny and hot, yet considerably cooler than Mediterranean summers moderated by breezes and regular rainfall. Although Varna receives about two thirds of the average rainfall for Bulgaria, abundant groundwater keeps its wooded hills lush throughout summer. The city is cut off from north and north-east winds by hills along the north arm of the bay, yet January and February still can be bitterly cold at times, with blizzards. Black Sea water has become cleaner after 1989 due to decreased chemical fertilizer in farming; it has low salinity, lacks large predators or poisonous species, and the tidal range is virtually imperceptible.

The city lies 470 km (292 mi) north-east of Sofia; the nearest major cities are Dobrich (45 km or 28 mi to the north), Shumen (80 km or 50 mi to the west), and Burgas (125 km or 78 mi to the south-west). Varna is accessible by air (Varna International Airport), sea (Port of Varna Cruise Terminal), railway (Central railway station), and car. Major roads include European routes E70 to Bucharest and E87 to Istanbul and Constanta, Romania; national motorways A-2 (Hemus motorway) to Sofia and A-5 (Cherno More motorway) to Burgas. There are bus lines to many Bulgarian and international cities from two bus terminals and train ferry and ro-ro services to Odessa, Ukraine, Port Kavkaz, Russia, Poti and Batumi, Georgia.

The public transit system is extensive and reasonably priced, with over 80 local and express bus, local trolleybus, and fixed-route minibus lines; there is a large fleet of taxicabs. In 2007, a number of double-decker buses were purchased; the mayor vowed that by summer 2008, all city buses would be retrofitted with air conditioners and later fueled by methane.

There is a plethora of Internet cafes and many places, including parks, are covered by free public wireless internet service. Varna is connected to other Black Sea cities by the submarine Black Sea Fibre Optic Cable System.

Climate

Varna has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), with considerable maritime and continental influences. The summer begins in early May and lasts till early October. Temperatures in summer usually vary between 18 C and 21 degrees C in the night and 25–35 C during the day. Seawater temperature during the summer months is usually around 23–27 degrees C. In winter temperatures are about 0 degrees at night and 5-10 degrees C during the day. Snow is possible in December, January, February and rarely in March. Snow falls in winter only several times and can quickly melt. The highest temperature ever recorded was 41.0 C and the lowest -19.0 C.

| Climate data for Varna (1952-2011) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 6.2 (43.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

14.8 (58.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

25.1 (77.2) |

27.8 (82) |

27.9 (82.2) |

23.9 (75) |

18.6 (65.5) |

12.8 (55) |

8.1 (46.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.9 (35.4) |

2.8 (37) |

5.7 (42.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

15.4 (59.7) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.4 (72.3) |

22.3 (72.1) |

18.3 (64.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.1 (39.4) |

12.2 (54) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −1.7 (28.9) |

−1.1 (30) |

1.7 (35.1) |

6.1 (43) |

10.8 (51.4) |

15.0 (59) |

17.2 (63) |

17.1 (62.8) |

13.5 (56.3) |

9.1 (48.4) |

4.6 (40.3) |

0.5 (32.9) |

7.8 (46) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 31.8 (1.252) |

29.9 (1.177) |

43.7 (1.72) |

57 (2.24) |

43.9 (1.728) |

57.6 (2.268) |

50.7 (1.996) |

41.4 (1.63) |

44.1 (1.736) |

42.6 (1.677) |

55.6 (2.189) |

42 (1.65) |

540.3 (21.272) |

| Average precipitation days | 13.5 | 11.3 | 11.9 | 9.3 | 6.9 | 6.2 | 4.7 | 3.3 | 6.5 | 9.6 | 8.9 | 11.5 | 103.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 77.9 | 75 | 73.3 | 73.7 | 74.8 | 72.5 | 69.7 | 69.4 | 73.1 | 77.6 | 78.1 | 79 | 74.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 89.9 | 102.2 | 142.6 | 180.0 | 248.0 | 270.0 | 300.7 | 299.2 | 219.0 | 167.4 | 105.0 | 79.1 | 2,203 |

| Source: Climatebase.ru[8] | |||||||||||||

History

Prehistory

Prehistoric settlements best known for the eneolithic necropolis (mid-5th millennium BC radiocarbon dating), a key archaeological site in world prehistory, eponymous of old European Varna culture and internationally considered the world's oldest large find of gold artifacts, existed within modern city limits. In the wider region of the Varna lakes (before the 1900s, freshwater) and the adjacent karst springs and caves, over 30 prehistoric settlements have been unearthed with the earliest artifacts dating back to the Middle Paleolithic or 100,000 years ago.

Antiquity and Bulgarian conquest

The region of ancient Thrace was populated by Thracians by 1000 BC. Miletian Greeks founded the apoikia (trading post) of Odessòs towards the end of the 7th century BC (the earliest Greek archaeological material is dated 600–575 BC), or, according to Pseudo-Scymnus, in the time of Astyages (here, usually 572–570 BC is suggested), within an earlier Thracian settlement. The name Odessos could have been pre-Greek, arguably of Greek Carian origin. A member of the Pontic Pentapolis, Odessos was a mixed community—contact zone between the Ionian Greeks and the Thracian tribes (Getae, Krobyzoi, Terizi) of the hinterland. Excavations at nearby Thracian sites have shown uninterrupted occupation from the 7th to the 4th century BC and close commercial relations with the colony. The Greek alphabet has been applied to inscriptions in Thracian since at least the 5th century BC; the city worshipped a Thracian great god whose cult survived well into the Roman period (Reference is needed).

Odessos was included in the assessment of the Delian league of 425 BC. In 339 BC, it was unsuccessfully besieged by Philip II (priests of the Getae persuaded him to conclude a treaty) but surrendered to Alexander the Great in 335 BC, and was later ruled by his diadochus Lysimachus, against whom it rebelled in 313 BC as part of a coalition with other Pontic cities and the Getae. The Roman city, Odessus, first included into the Praefectura orae maritimae and then in 15 AD annexed to the province of Moesia (later Moesia Inferior), covered 47 hectares in present-day central Varna and had prominent public baths, Thermae, erected in the late 2nd century AD, now the largest Roman remains in Bulgaria (the building was 100 m (328.08 ft) wide, 70 m (229.66 ft) long, and 25 m (82.02 ft) high) and fourth-largest known Roman baths in Europe. Major athletic games were held every five years, possibly attended by Gordian III in 238 CE.

Odessus was an early Christian centre, as testified by ruins of ten early basilicas,[9] a monophysite monastery, and indications that one of the Seventy Disciples, Ampliatus, follower of Saint Andrew (who, according to the Bulgarian Orthodox Church legend, preached in the city in 56 CE), served as bishop there. In 6th-century imperial documents, it was referred to as "holiest city," sacratissima civitas. In 442 CE, a peace treaty between Theodosius II and Attila was conducted at Odessus. In 513, it became a focal point of the Vitalian revolt. In 536, Justinian I made it the seat of the Quaestura exercitus ruled by a prefect of Scythia or quaestor Justinianus and including Lower Moesia, Scythia, Caria, the Aegean Islands and Cyprus; later, the military camp outside Odessus was the seat of another senior Roman commander, magister militum per Thracias.

It has been suggested that the 681 AD peace treaty with the Byzantine Empire that established the new Bulgarian state was concluded at Varna and the first Bulgarian capital south of the Danube may have been provisionally located in its vicinity—possibly in an ancient city near Lake Varna's north shore named Theodorias (Θεοδωριάς) by Justinian I—before it moved to Pliska 70 kilometres (43 miles) to the west.[10] Asparukh fortified the Varna river lowland by a rampart against a possible Byzantine landing; the Asparuhov val (Asparukh's Wall) is still standing. Numerous 7th-century Bulgar settlements have been excavated across the city and further west; the Varna lakes north shores, of all regions, were arguably most densely populated by Bulgars. It has been suggested that Asparukh was aware of the importance of the Roman military camp (campus tribunalis) established by Justinian I outside Odessus and considered it (or its remnants) as the legitimate seat of power for both Lower Moesia and Scythia.

Middle Ages

Control changed from Byzantine to Bulgarian hands several times during the Middle Ages. In the late 9th and the first half of the 10th century, Varna was the site of a principal scriptorium of the Preslav Literary School at a monastery endowed by Boris I who may have also used it as his monastic retreat. The scriptorium may have played a key role in the development of Cyrillic script by Bulgarian scholars under the guidance of one of Saints Cyril and Methodius' disciples. Karel Škorpil suggested that Boris I may have been interred there. The synthetic culture with Hellenistic Thracian, Roman, as well as eastern—Armenian, Syrian, Persian—traits that developed around Odessus in the 6th century under Justinian I, may have influenced the Pliska-Preslav culture of the First Bulgarian Empire, ostensibly in architecture and plastic decorative arts, but possibly also in literature, including Cyrillic scholarship. In 1201, Kaloyan took over the Varna fortress, then in Byzantine hands, on Holy Saturday using a siege tower, and secured it for the Second Bulgarian Empire.

By the late 13th century, with the Treaty of Nymphaeum of 1261, the offensive-defensive alliance between Michael VIII Palaeologus and Genoa that opened up the Black Sea to Genoese commerce, Varna had turned into a thriving commercial port city frequented by Genoese and later also by Venetian and Ragusan merchant ships. The first two maritime republics held consulates and had expatriate colonies there (Ragusan merchants remained active at the port through the 17th century operating from their colony in nearby Provadiya). The city was flanked by two fortresses with smaller commercial ports of their own, Kastritsi and Galata, within sight of each other, and was protected by two other strongholds overlooking the lakes, Maglizh and Petrich. Wheat, animal skins, honey and wax, wine, timber and other local agricultural produce for the Italian and Constantinople markets were the chief exports, and Mediterranean foods and luxury items were imported. The city introduced its own monetary standard, the Varna perper, by the mid-14th century; Bulgarian and Venetian currency exchange rate was fixed by a treaty. Fine jewelry, household ceramics, fine leather and food processing, and other crafts flourished; shipbuilding developed in the Kamchiya river mouth.

14th-century Italian portolan charts showed Varna as arguably the most important seaport between Constantinople and the Danube delta; they usually labeled the region Zagora. The city was unsuccessfully besieged by Amadeus VI of Savoy, who had captured all Bulgarian fortresses to the south of it, including Galata, in 1366. In 1386, Varna briefly became the capital of the spinoff Principality of Karvuna, then was taken over by the Ottomans in 1389 (and again in 1444), ceded temporarily to Manuel II Palaeologus in 1413 (perhaps until 1444), and sacked by Tatars in 1414.

Battle of Varna

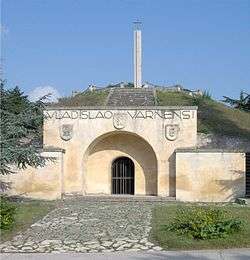

On 10 November 1444, one of the last major battles of the Crusades in European history was fought outside the city walls. The Turks routed an army of 20,000-30,000 crusaders[11] led by Ladislaus III of Poland (also Ulászló I of Hungary), which had assembled at the port to set sail to Constantinople. The Christian army was attacked by a superior force of 55,000 or 60,000 Ottomans led by sultan Murad II. Ladislaus III was killed in a bold attempt to capture the sultan, earning the sobriquet Warneńczyk (of Varna in Polish; he is also known as Várnai Ulászló in Hungarian or Ladislaus Varnensis in Latin). The failure of the Crusade of Varna made the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans in 1453 all but inevitable, and Varna (with all of Bulgaria) was to remain under Ottoman domination for over four centuries. Today, there is a cenotaph of Ladislaus III in Varna.

Late Ottoman rule

A major port, agricultural, trade and shipbuilding centre for the Ottoman Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries, preserving a significant and economically active Bulgarian population, Varna was later made one of the Quadrilateral Fortresses (along with Rousse, Shumen, and Silistra) severing Dobruja from the rest of Bulgaria and containing Russia in the Russo-Turkish wars. The Russians temporarily took over in 1773 and again in 1828, following the prolonged Siege of Varna, returning it to the Ottomans two years later after the medieval fortress was razed.

In the early 19th century, many local Greeks joined the patriotic organization Filiki Eteria. Αt the outbreak of the Greek War of Independence (1821) revolutionary activity was recorded in Varna. As a result local notables that participated in the Greek national movement were executed by the Ottoman authorities, while others managed to escape to Greece and continue their struggle.[12]

The British and French campaigning against Russia in the Crimean War (1854–1856) used Varna as headquarters and principal naval base; many soldiers died of cholera and the city was devastated by a fire. A British and a French monument mark the cemeteries where cholera victims were interred. In 1866, the first railroad in Bulgaria connected Varna with the Rousse on the Danube, linking the Ottoman capital Constantinople with Central Europe; for a few years, the Orient Express ran through that route. The port of Varna developed as a major supplier of food—notably wheat from the adjacent breadbasket Southern Dobruja—to Constantinople and a busy hub for European imports to the capital; 12 foreign consulates opened in the city. Local Bulgarians took part in the National Revival; Vasil Levski set up a secret revolutionary committee.

Third Bulgarian State

In 1878, the city, which numbered 26 thousand inhabitants, was given to Bulgaria by the Russian troops, who entered on 27 July. Varna became a front city in the First Balkan War and the First World War; its economy was badly affected by the temporary loss of its agrarian hinterland of Southern Dobruja to Romania (1913–16 and 1919–40). In the Second World War, the Red Army occupied the city in September 1944, helping cement communist rule in Bulgaria.

One of the early centres of industrial development and the Bulgarian labor movement, Varna established itself as the nation's principal port of export, a major grain producing and viticulture centre, seat of the nation's oldest institution of higher learning outside Sofia, a popular venue for international festivals and events, as well as the country's de facto summer capital with the erection of the Euxinograd royal summer palace (currently, the Bulgarian government convenes summer sessions there). Mass tourism emerged since the late 1950s. Heavy industry and trade with the Soviet Union boomed in the 1950s to the 1970s.

From 20 December 1949 to 20 October 1956 the city was renamed by the communist government Stalin after Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin.[13]

In 1962, the 15th Chess Olympiad, also known as the World Team Championship, was here. In 1969 and 1987, Varna was the host of the World Rhythmic Gymnastics Championships. From 30 September to 4 October 1973, the 10th Olympic Congress took place in the Sports Palace.

Varna became a popular resort for Eastern Europeans, until 1989 barred from travelling to the west. One of them, the veteran German Communist Otto Braun died while on a vacation in Varna in 1974.

Economy

The economy is service-based, with 61% of net revenue generated in trade and tourism, 16% in manufacturing, 14% in transportation and communications, and 6% in construction.[14] Financial services, particularly banking, insurance, investment management, and real-estate finance are booming. As of December 2008, the fallout of the global financial crisis has not yet been hard. The city is the easternmost destination of Pan-European transport corridor 8 and is connected to corridors 7 and 9 via Rousse. Major industries traditionally include transportation (Navibulgar, Port of Varna, Varna International Airport), distribution (Logistics Park Varna[15]), shipbuilding (see also Oceanic-Creations), ship repair,[16] and other marine industries.

In June 2007, Eni and Gazprom disclosed the South Stream project whereby a 900-kilometre-long (559-mile) offshore natural gas pipeline from Russia's Dzhubga with annual capacity of 63 billion metres (207 billion feet) is planned to come ashore at Varna, possibly near the Galata offshore gas field, en route to Italy and Austria.

With the nearby towns of Beloslav and Devnya, Varna forms the Varna-Devnya Industrial Complex, home to some of the largest chemical, thermal power, and manufacturing facilities in Bulgaria, including Varna Thermal Pover Plant and Sodi Devnya, the two largest cash privatization deals in the country's recent history. There are also notable facilities for radio navigation devices, household appliances, security systems, textiles, apparel, food and beverages, printing, and other industries. Some manufacturing veterans are giving way to post-industrial developments: an ECE shopping mall is taking the place of the former VAMO diesel engine works and the Varna Brewery is being replaced by a convention centre.

Tourism is of foremost importance with the suburban beachfront resorts of Golden Sands, Holiday Club Riviera, Sunny Day, Constantine and Helena, and others with a total capacity of over 60,000 beds (2005), attracting millions of visitors each year (4.74 million in 2006, 3.99 million of which international tourists[17]). The resorts received considerable internal and foreign investment in the late 1990s and early in the first decade of the 21st century, and are environmentally sound, being located reassuringly far from chemical and other smokestack industries. Varna is also Bulgaria's only international cruise destination (with over 30 cruises scheduled for 2007) and a major international convention and spa centre.

Real estate boomed in 2003–2008 with some of the highest prices in the nation, by fall 2007 surpassing Sofia (this still holds true in April 2009). Commercial real estate is developing major international office tower projects.[18][19][20]

In retail, the city not only has the assortment of international big-box retailers[21] now ubiquitous in larger Bulgarian cities, but boasts made-in-Varna national chains with locations spreading over the country such as retailer Piccadilly, restaurateur Happy,[22] and pharmacy chain Sanita.

In 2008, there were three large shopping malls operating and another four projects in various stages of development, turning Varna into an attractive international shopping destination (Pfohe Mall, Central Plaza, Mall Varna, Grand Mall, Gallery Mall, Cherno More Park, and Varna Towers),[23] plus a retail park under development outside town. The city has many of the finest eateries in the nation and abounds in ethnic food places.

Economically, Varna is among the best-performing and fastest-growing Bulgarian cities; unemployment, at 2.34% (2007), is over 3 times lower than the nation's rate; in 2007, median salary was the highest,[24] on a par with Sofia and Burgas. Many Bulgarians regard Varna as a boom town; some, including from Sofia and Plovdiv, or returning from western countries, but mostly from Dobrich, Shumen, and the greater region, are relocating there.

In September 2004, FDi magazine (a Financial Times Business Ltd publication) proclaimed Varna South-eastern Europe City of the Future[25] citing its strategic location, fast-growing economy, rich cultural heritage and higher education. In April 2007, rating agency Standard & Poor's announced that it had raised its long-term issue credit rating for Varna to BB+ from BB, declaring the city's outlook "stable" and praising its "improved operating performance".[17]

In December 2007 (and again in October 2008), Varna was voted "Best City in Bulgaria to Live In"[26] by a national poll by Darik Radio, the 24 Chasa daily and the information portal darik.news.

Population

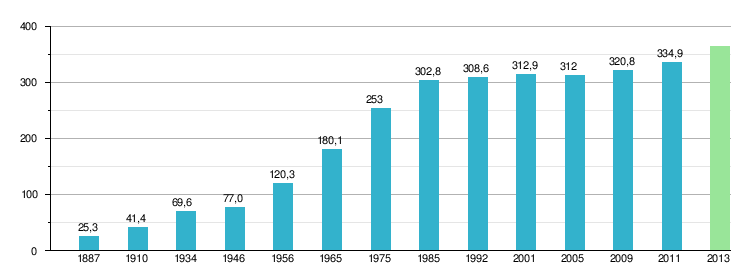

The first population data date back to the mid-17th century when the town was thought to have about 4,000 inhabitants,[27] while the first population census in 1881 counted 24,555.[28] According to the 1883 census, it was the second-largest in Bulgaria after Ruse. Thereafter Varna became Bulgaria's third-largest city and kept this position steadily for the next 120 years, while different cities took turns in the first, second, and fourth places.

In January 2012, the city of Varna has a population of 334 781, which makes it the third largest city in Bulgaria, while the Varna Municipality along with the legally affiliated adjacent villages had 343 643 inhabitants.[29] The unofficial metro area (including Varna municipality and adjacent parts of Aksakovo, Avren, Beloslav, and Devnya municipalities, and excluding adjacent parts of Dobrich Province) has an estimated population of 475,000.[30] Here, the "Varna-Devnya-Provadiya agglomeration" is not considered identical to the "Varna metro area".

Varna is one of the few cities in Bulgaria with a positive natural growth (6300 births vs. 3600 deaths in 2009[31]) and new children's day care centers opening (6 expected in 2009).[32]

Since December 2006, various sources, including the Bulgarian National Television, national newspapers, research agencies, the mayor's office, and local police, claim that Varna has a population by present address of over 500,000, making it the nation's second-largest city.[33][34] Official statistics according to GRAO and NSI, however, have not supported their claims. In 2008, Deputy Mayor Venelin Zhechev estimated the actual population at 650,000.[35] In December 2008, Mayor Kiril Yordanov claimed the actual number of permanent residents was 970,000,[36] or that there were 60% unregistered people. In January 2009, the Financial Times said that "Varna now draws about 30,000 new residents a year."[37] The census, carried out in February, 2011, enumerated 334,870 inhabitants. If unregistered population plus the commuters from the adjacent municipalities are taken into consideration, the real population of the city during a work day reaches 360,000. Varna attracts 2 to 3 million tourists a year, as the holidaymakers may reach as many as 200,000 daily during the high season. Thus, there are about 560,000 people in the city in July and August.

| Varna | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1887 | 1910 | 1934 | 1946 | 1956 | 1965 | 1975 | 1985 | 1992 | 2001 | 2005 | 2009 | 2011 | 2013 | |

| Population | 25,256 | 41,419 | 69,563 | 76,954 | 120,345 | 180,633 | 253,039 | 302,816 | 308,601 | 312,889 | 312,026 | 320,837 | 334,870 | ?? | |

| Highest number ' in ' | |||||||||||||||

| Sources: National Statistical Institute,[38][39][40] „citypopulation.de“,[41] „pop-stat.mashke.org“,[42] Bulgarian Academy of Sciences[43] | |||||||||||||||

Ethnic, linguistic and religious composition

Most Varnians (варненци, varnentsi) are ethnic Bulgarians (94%). Ethnic Turks rank second with 3%, however by 2009, Russians and other Russian-speaking recent immigrants with no Bulgarian citizenship, estimated at over 20,000, perhaps have outnumbered them, additionally there is a growing number of new Asian and African immigrants and corporate expatriates. There is a comparable number of Gypsies (1% of the population) mostly in three distinctive and largely impoverished ghetto neighborhoods: Maksuda; Rozova Dolina in the Asparuhovo district; and Chengene Kula in the Vladislavovo district, while Varna is spearheading several programs on Gypsy integration. Armenians, Greeks, Jews, and other long-standing ethnic groups are also present although in much smaller numbers. At the Liberation of Bulgaria, ethnic Bulgarians were 3,500 of the total population of 21,000 inhabitants. According to the 1881 census, the Turkish language was a mother tongue for 8903 people (36,25%), for 6721 was the Bulgarian (27,36%), for 5,367 was Greek (21,85%) and Tatar for 837 (3,41%). By ethnic group, ethnic Bulgarians were then 6,714, of whom 4478 men and 2236 women.[44] With the departure of most Turks and Greeks and the arrival of Bulgarian refugees and settlers from inland, Northern Dobruja, Bessarabia, and Asia Minor, and later, of refugees from Macedonia, Eastern Thrace and Southern Dobruja following the Second Balkan War and the First World War, ethnic diversity gave way to Bulgarian predominance, although sizeable minorities of Gagauz, Armenians, and Sephardic Jews remained for decades.

According to the latest 2011 census data, the individuals declared their ethnic identity were distributed as follows:[45][46]

- Bulgarians: 284,738 (93.8%)

- Turks: 10,028 (3.6%)

- Gypsies: 3,162 (1.0%)

- Others: 3,378 (1.1%)

- Indefinable: 2,288 (0.8%)

- Undeclared: 31,276 (10.3%)

Total: 334,781

In Varna Municipality 290,780 declared as Bulgarians, 11,089 as Turks, 3,535 as Gypsies and 34,758 did not declare their ethnic group.

According to the 2001 census data, the ethnic composition was as follows:[47]

- Bulgarians: 296,407 (92.5%)

- Turks: 12,295 (3.8%)

- Gypsies: 3,748 (1.2%)

- Others: 4,566 (1.4%)

- Indefinable: 2,406 (0.8%)

- Undeclared: 1,042 (0.3%)

Total: 320,464

City government

The municipality (община, obshtina, commune) of Varna comprises the city and five suburban villages: Kamenar, Kazashko, Konstantinovo, Topoli, and Zvezditsa, served by the city public transit system.

Executive

The municipal chief executive is the mayor (кмет, kmet: the word is cognate with count). Since the end of the de facto one-party communist rule in 1990, there have been three mayors: Voyno Voynov, SDS (Union of Democratic Forces), ad interim, 1990–91; Hristo Kirchev, SDS, 1991–99; Kiril Yordanov, independent, 1999–present. Yordanov was reelected for a third consecutive term in 2007.[48] Varna Peninsula on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands.

Legislative

As of January 2009, the city council (общински съвет, obshtinski savet, the 51-member legislature) is composed as follows: centre-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), 9 council members; centre-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB), 9; Dvizhenie Nashiyat Grad (Our Town Movement, a local group supporting mayor Yordanov), 6; Red, Zakonnost i Spravedlivost (Order, Rule of Law, and Justice), 5; the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), 4; coalition of SDS and Democrats for a Strong Bulgaria (DSB), another centre-right party, 3; other groups and independents, 15. Borislav Gutsanov (BSP) is council chairman.[49]

Party politics

The largest political parties in the city are BSP, GERB and SDS, with the National Movement for Stability and Progress (NDSV) as a distant fourth; DSB, the Bulgarian Democratic Party, the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (IMRO, VMRO), and Ataka are also active. SDS took a heavy hit in early 2009 as its local leader's student son was charged with the brutal murder of a young woman. Local business groups have formed political parties for recent local elections, setting a national trend.

Varna is currently (March 2009) represented by five ministers in Sergey Stanishev's cabinet: Deputy Prime Minister Meglena Plugchieva (BSP, Administration of EU Funds), Nikolay Vasilev (NDSV, State Administration), Daniel Valchev (NDSV, Education and Science), Miglena Tacheva (BSP, Justice), and Petar Dimitrov (BSP, Economy and Energy). Among other noted Varna politicians are Ilko Eskenazi (SDS), Aleksandar Yordanov (SDS), Borislav Ralchev (NDSV), and Nedelcho Beronov (independent).

Judicial

The city is the seat of a regional, district, administrative, and military court, and a court of appeal; regional, military, and appellate prosecutor's offices.[50]

Consulates

There are consulates of the following countries: the Czech Republic, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Malta, Poland, Russia, Slovakia, Sweden, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.[51]

Boroughs and urban planning

The city is divided by law into five boroughs (райони, rayoni), each with its mayor and council: Asparuhovo, Mladost, Odessos (the historic centre), Primorski (the largest one with official population of 102,000 also comprising the seaside resorts north of the city centre), and Vladislav Varchenchik. The boroughs are composed of various districts with distinctive characters and histories.[52] The villages too have а mayor or a mayoral lieutenant (кметски наместник, kmetski namestnik).

As of January 2009, a heated public discussion of a new draft general plan has been under way for a few months; it is expected to be passed by the city council later this year.[53] According to the Financial Times, "A new city master plan, due to be launched this year [2009], will be a 21st-century take on King Ferdinand's grand scheme. Among other projects, the commercial port will be moved to a new site on an inland lagoon to the west of the city, opening up space for what would become the Black Sea's largest and best-equipped marina. The plan will allow for a major redevelopment of the port site [with] luxury homes, hotels, restaurants."[37] The quay streets of the new waterfront are deemed important for opening the urbanscape to the sea as most of the coast is framed by parks.

- List of Varna City boroughs and districts

| District | Cyrillic | Borough | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vladislav Varnenchik | Владислав Варненчик | Vladislav Varnenchik | 48,740 |

| Kaisieva Gradina (Apricot Garden) | Кайсиева градина | Vladislav Varnenchik | 48,740 |

| Troshevo | Трошево | Mladost | 87,256 |

| Mladost (Youth) | Младост | Mladost | 87,256 |

| Chayka (Seagull) | Чайка | Primorski | 105,340 |

| Central borough | Център | Odessos | 82,784 |

| Asparuhovo | Аспарухово | Asparuhovo | 27,178 |

| Vinitza | Виница | Primorski | 105,340 |

| Zlatni pyasatsi (Golden Sands) | Златни пясъци | Primorski | 105,340 |

| Hristo Botev | Христо Ботев | Odessos | 82,784 |

| Galata | Галата | Asparuhovo | 27,178 |

| Vazrazhdane (Revival) | Възраждане | Mladost | 87,256 |

| Pobeda (Victory) | Победа | Mladost | 87,256 |

| Zapadna promishlena zona (West Industrial Zone) | Западна промишлена зона | Mladost | 87,256 |

Main sights

City landmarks include the Varna Archaeological Museum, exhibiting the Gold of Varna, the Roman Baths, the Battle of Varna Park Museum, the Naval Museum in the Italianate Villa Assareto displaying the museum ship Drazki torpedo boat, the Museum of Ethnography in an Ottoman-period compound featuring the life of local urban dwellers, fisherfolk, and peasants in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The 'Sea Garden' is the oldest and perhaps largest park in town containing an open-air theatre (venue of the International Ballet Competition, opera performances and concerts), Varna Aquarium (opened 1932), the Festa Dolphinarium (opened 1984), the Nicolaus Copernicus Observatory and Planetarium, the Museum of Natural History, a terrarium, a zoo, an alpineum, a children's amusement park with a pond, boat house and ice-skating rink, and other attractions. The National Revival Alley is decorated with bronze monuments to prominent Bulgarians, and the Cosmonauts' Alley contains trees planted by Yuri Gagarin and other Soviet and Bulgarian cosmonauts. The Garden is a national monument of landscape architecture and is said to be the largest landscaped park in the Balkans.

The waterfront promenade is lined by a string of beach clubs offering a vibrant scene of rock, hip-hop, Bulgarian and American-style pop, techno, and chalga. In October 2006, The Independent dubbed Varna "Europe's new funky-town, the good-time capital of Bulgaria".[54] The city enjoys a nationwide reputation for its rock, hip-hop, world music, and other artists, clubs, and related events such as July Morning and international rock and hip-hop (including graffiti[55]) venues.

The city beaches, also known as sea baths (морски бани, morski bani), are dotted with hot (up to 55°С/131 °F) sulphuric mineral water sources (used for spas, swimming pools and public showers) and punctured by small sheltered marinas. Additionally, the 2.05 km (1.27 mi) long, 52 m (171 ft) high Asparuhov most bridge is a popular spot for bungee jumping. Outside the city are the Euxinograd palace, park and winery, the University of Sofia Botanical Garden (Ecopark Varna), the Pobiti Kamani rock phenomenon, and the medieval cave monastery, Aladzha.

Tourist shopping areas include the boutique rows along Prince Boris Blvd (with retail rents rivaling Vitosha Blvd in Sofia) and adjacent pedestrian streets, as well as the large mall and big-box cluster in the Mladost district, suitable for motorists. Two other shopping plazas, Piccadilly Park and Central Plaza, are conveniently located to serve tourists in the resorts north of the city centre, both driving and riding the public transit. ATMs and 24/7 gas stations with convenience stores abound.

Food markets, among others, include supermarket chains Piccadilly and Burleks. In stores and restaurants, credit cards are normally accepted. There is a number of farmers markets offering fresh local produce; the Kolkhozen Pazar, the largest one, also has a fresh fish market but is located in a crowded area virtually inaccessible for cars.

Like other cities in the region, Varna has its share of stray dogs, for the most part calm and friendly, flashing orange clips on the ears showing they have been castrated and vaccinated. However, urban wildlife is dominated by the ubiquitous seagulls, while brown squirrels inhabit the Sea Garden. In January and February, migrating swans winter on the sheltered beaches.[56]

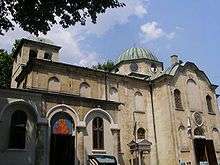

Churches

Notable old Bulgarian Orthodox temples include the metropolitan Dormition of the Theotokos Cathedral (of the diocese of Varna and Veliki Preslav); the early 17th-century Theotokos Panagia (built on the site of an earlier church where Ladislaus III was perhaps buried); the St. Athanasius (former Greek metropolitan cathedral) on the footprint of a razed 10th-century church; the 15th-century St. Petka Parashkeva chapel; the seamen's church of Saint Nicholas; the Archangel Michael chapel, site of the first Bulgarian secular school from the National Revival era; and the Sts. Constantine and Helena church of the 14th-century suburban monastery of the same name.

The remains of a large 4th–5th-century stronghold basilica in Dzhanavara Park just south of town are becoming a tourist destination with some exquisite mosaics displayed in situ. The remains of another massive 9th-century basilica adjacent to the scriptorium at Boris I's Theotokos Panagia monastery are being excavated and conserved. A 4th–5th-century episcopal basilica north of the Thermae is also being restored. There is also a number of newer Orthodox temples; two, dedicated to apostle Andrew and the local martyr St. Procopius of Varna, are currently under construction. Many smaller Orthodox chapels have mushroomed in the area. In early 2009, Vasil Danev, leader of the ethnic Organization of the United Roma Communities (FORO), said local Roma would also erect an Orthodox chapel.

There is an old Armenian Apostolic church; two Roman Catholic churches (only one is now open and holds mass in Polish on Sundays), a thriving Evangelical Methodist episcopal church offering organ concerts, active Evangelical Pentecostal, Seventh-day Adventist, and two Baptist churches.

Two old mosques (one is open) have survived since Ottoman times, when there were 18 of them in town, as have two once stately but now dilapidated synagogues, a Sephardic and an Ashkenazic one, the latter in Gothic style (it is undergoing restoration). A new mosque was recently added in the southern Asparuhovo district serving the adjacent Muslim Roma neighborhood.

There is also a Buddhist centre.

On a different note, spiritual master Peter Deunov started preaching his Esoteric Christianity doctrine in Varna in the late 1890s, and, in 1899–1908, the yearly meetings of his Synarchic Chain, later known as the Universal White Brotherhood, were convened there.

Architecture

By 1878, Varna was an Ottoman city of mostly wooden houses in a style characteristic of the Black Sea coast, densely packed along narrow, winding lanes.[57][58] It was surrounded by a stone wall restored in the 1830s with a citadel, a moat, ornamented iron gates flanked by towers, and a vaulted stone bridge across the River Varna. The place abounded in pre-Ottoman relics, ancient ruins were widely used as stone quarries.

Today, very little of this legacy remains; the city centre was rebuilt by the nascent Bulgarian middle class in late 19th and early 20th centuries in Western style with local interpretations of Neo-Renaissance, Neo-Baroque, Neoclassicism, Art Nouveau and Art Deco (many of those buildings, whose ownership was restored after 1989, underwent renovations).

Stone masonry from demolished city walls was used for the cathedral, the two elite high schools, and for paving new boulevards. The middle class built practical townhouses and coop buildings. Elegant mansions were erected on main boulevards and in the vineyards north of town. A few industrial working-class suburbs (of one-family cottages with small green yards) emerged. Refugees from the 1910s' wars also settled in similar poorer yet vibrant neighbourhoods along the city edges.

During the rapid urbanization of the 1960s to the early 1980s, large apartment complexes sprawled onto land formerly covered by small private vineyards or agricultural cooperatives as the city population tripled. Beach resorts were designed mostly in a sleek modern style, which was somewhat lost in their recent more lavish renovations. Modern landmarks of the 1960s include the Palace of Culture and Sports, built in 1968.

With the country's return to capitalism since 1989, upscale apartment buildings mushroomed both downtown and on uptown terraces overlooking the sea and the lake. Varna's vineyards (лозя, lozya), dating back perhaps to antiquity and stretching for miles around, started turning from mostly rural grounds dotted with summer houses or vili into affluent suburbs sporting opulent villas and family hotels, epitomized by the researched postmodernist kitsch of the Villa Aqua.

With the new suburban construction far outpacing infrastructure growth, ancient landslides were activated, temporarily disrupting major highways. As the number of vehicles quadrupled since 1989, Varna became known for traffic jams; parking on the old town's leafy but narrow streets normally takes the sidewalks. At the same time, stretches of shanty towns, more befitting Rio de Janeiro, remain in Romani neighbourhoods on the western edge of town due to complexities of local politics.

The beach resorts were rebuilt and expanded, fortunately without being as heavily overdeveloped as were other tourist destinations on the Bulgarian Black Sea coast, and their greenery was mostly preserved. New modern office buildings started reshaping the old centre and the city's surroundings.[59][60]

Education

Higher learning institutions

The University of Economics, founded in 1920 as the Higher Business School, is the second oldest Bulgarian university, the oldest one outside Sofia, and the first private one—underwritten by the Varna Chamber of Commerce and Industry. Prof. Tsani Kalyandzhiev, who was educated at Zürich and made a career as a research chemist in the United States, was its first Rector (President).

The Nikola Vaptsarov Naval Academy is successor to the nation's oldest technical school, the Naval Machinery School, established in 1881 and renamed His Majesty's Naval Academy in 1942. Other higher schools include the Medical University, the Technical University, the Chernorizets Hrabar Varna Free University — the first private university in the land after 1989, three junior colleges, and two local branches of other Bulgarian universities.

There are five Bulgarian Academy of Sciences research institutes (of oceanology, fisheries, aero and hydrodynamics, and metallography) and Varna-Europa Academy, a government research institution (shipping), and a now-defunct naval architecture design bureau. The Institute of Oceanology (IO-BAS) has been active in Black Sea deluge theory studies and deepwater archaeology in cooperation with Columbia University, MIT, UPenn, and National Geographic.

In 2007, Varna was home to a total of 2,500 faculty and researchers and over 30,000 students.

Local universities:

- University of Economics and College of Tourism

- Nikola Vaptsarov Naval Academy

- Technical University and Varna College

- Prof. Paraskev Stoyanov Medical University and Medical College

- Chernorizets Hrabar Varna Free University

Other universities' local branches:

- New Bulgarian University Local Centre Varna

- Bishop Constantine of Preslav University of Shumen Teacher Information and Qualification Centre (graduate)

- Varna-Europa[61]

Noted high schools

- First Language School (English and German)

- Dr. Petar Beron Second High School of Mathematics

- Acad. Metodi Popov Third High School of Science and Mathematics

- Frédéric Joliot-Curie Fourth Language School (French and Spanish)

- John Exarch Fifth Language School (English, German, and French)

- Constantine of Preslav National High School for the Humanities and Arts

- Dobri Hristov National School of Arts (instrumental and vocal music, dance, and visual arts)

- Private Trade School (offering opportunities for international students and distance education)

Libraries

- Pencho Slaveikov Public Library

Culture

Varna has some of the finest and oldest museums, professional arts companies, and arts festivals in the nation and is known for its century-old traditions in visual arts, music, and book publishing, as well as for its bustling current pop-culture scene. Over the past few decades, it developed as a festival centre of international standing. Varna is a front-runner for European Capital of Culture for 2019, planning to open several new high-profile facilities such as a new opera house and concert hall, a new exhibition centre, and a reconstruction of the Summer Theatre, the historic venue of the International Ballet Competition.

Museums

- Varna Archaeological Museum (founded 1888)

- Naval Museum (founded 1923)

- Roman Baths

- Aladzha Monastery

- Battle of Varna Park Museum (founded 1924)

- Museum of Ethnography

- National Revival Museum

- History of Varna Museum

- History of Medicine Museum

- Health Museum (children's)

- Puppet Museum (antique puppets from Puppet Theatre shows)

- Bulgar Settlement of Phanagoria ethnographical village (mockup, with historical reenactments)

- Aquarium (founded 1912)

- Nicolaus Copernicus Observatory and Planetarium

- Naval Academy Planetarium

- Museum of Natural History

- Terrarium

- Varna Zoo

- Dolphinarium (founded 1984)

Galleries

- Boris Georgiev Art Gallery

- Georgi Velchev Gallery

- Modern Art Centre (Graffit Gallery Hotel)

- Print Gallery

- Numerous smaller fine and applied arts galleries[62]

Performing arts professional companies

- Opera and Philharmonic Society (opera, symphonic and chamber music, ballet, and operetta performances; earliest philharmonic society founded 1888)

- Stoyan Bachvarov Drama Theatre (founded 1921)

- State Puppet Theatre Varna[63] (in Bulgarian, founded 1952; often cited as the finest one in the nation, performances for children and adults)

- Bulgarian Theatre

- Varna Ensemble (traditional folk music and dance)

Art networks

- Scenderman art network (music and visual art)

Other performing arts groups

- Morski Zvutsi Choir School (academic choirs)

- Dobri Hristov Choir School (academic choir)

Notable bands and artists

- Daniela Dimova & Janette Benun – Scenderman Network[64] (Sepharadic chamber music)

- Nikolay Yordanov – Scenderman Network[64] (ethno, art, folklore)

- Deep Zone (tech house/Euro)

- Dede-dessert[65] (house/electro)

- DJ Balthazar (underground electronic dance)

- The SektorZ (electronic/hard dance)

- Big Sha and the Gumeni glavi (Rubber Heads) (hip hop)

- 100 Kila (hip hop)

- Elitsa Todorova (ethnic & electro)

- Indignity (hardcore)

- Outrage (hardcore)

- Cold Breath (metalcore)

- One Faith (hardcore)

- Crowfish (progressive/punk/indie)

- Maniacal Pictures (alternative/rock/post punk)

- Pizza (punk/ska/rock)

- A-Moral (punk/hardcore)

- On Our Own (hardcore)

- Sealed In Blood (hardcore/metal)

- ENE (alternative/folk/other)

- Gergana (pop/techno/ethnic)

- Zayo Bayo Gives Me The Creeps (death thrash)

- La Migra (funk/jazz/ethnic)

- Georgi Lechev (artist)

- Nikolay Roussev[64] (artist)

- Marina Varentzova-Rousseva[64] (artist)

- Nelko Kolarov (composer, musician)

- Desko Nikolov (musician/folk)

Other institutions

- Festival and Congress Centre (in Bulgarian, 1986; concerts, film, theatre and dance shows, exhibitions, trade shows)

- Palace of Culture and Sports (1968; sports events, concerts, film shows, exhibitions, trade shows, sports classes, fitness)

International arts festivals

- Varna International Ballet Competition, founded 1964 (biennial)

- Varna Summer International Music Festival,[22] founded 1926 (annual)

- Without Borders[66] International art forum and Festival – Varna, Albena, Balchik (biannual)

- Varna Summer International Jazz Festival (annual)

- International May Choir Competition (annual)

- European Music Festival (annual)

- Operosa Euxinograd opera festival (annual)

- Sea and Memories international music festival devoted to popular sea songs (annual)

- International Folk Festival,[22] (annual)

- Discovery International Pop Festival (annual)

- Song on Three Seas pop and rock competition (annual)

- Brazilian Culture Festival (annual)

- Varna Summer International Theatre Festival (annual)

- Golden Dolphin Intenrtional puppet festival (triennial)

- Under the Stars arts festival (annual, theatre and opera)

- Zvezdna daga children's competition (annual)

- Love is Folly film festival (annual)

- International Festival of Red Cross & Health Films (biennial)

- World Animation Festival (founded 1979, to resume in 2009)

- International Print Biennial (founded 1981)

- August in Art festival of visual arts (triennial) (in Bulgarian)

- Videoholica international art festival (annual)

- product Festival of Contemporary Art (annual)

- Slavic Embrace Slav poetry readings (annual)

- Fotosalon (annual)

National events

- Golden Rose Bulgarian Feature Film Festival

- Got Flow National Hip-Hop Dance Festival (annual)

- May Arts Saloon at Radio Varna

- Bulgaria for All National Ethnic Festival (annual, minority authentic folklore)

- Dinyo Marinov National Children's Authentic Folklore Music Festival

- Morsko konche (Seahorse) children's vocal competition (annual, pop)

- Navy Day (second Sunday of August)

- Urban Folk Song Festival

- Christmas Folk Dance Competition

Local events

- Easter music festival

- Classical guitar festival

- Golden Fish fairy tale festival

- Kinohit movie marathon

- Crafts fair (August 2012)

- Dormition of the Theotokos festival, cathedral patron, Varna Day (August 15)

- Beer Fest

- Saint Nicholas Day (December 6)

- Christmas festival

- New Year's Eve concert and fireworks (Independence Square)

- Operosa Opera Festival

Media

As early as the 1880s, numerous daily and weekly newspapers were published in Bulgarian and several minority languages. Radio Varna opened in 1934. Galaktika book publishing house occupied a prominent place nationally in the 1970–1990s, focusing on international sci-fi and marine fiction, contemporary non-fiction and poetry.

Local newspapers

- Cherno More

- Chernomorie

- Narodno Delo

- Dialog – free positive newspaper (weekly)

- Pozvanete

- Varna (weekly)

- Vlastta (online publication)

- Varna Utre

National newspapers' local editions

- 24 Chasa More

- Morski Dnevnik

- Morski Trud[67]

Magazines

- Morski Sviat

- Prostori

Publishing houses

- Alfiola (New Age)

- Alpha Print (advertising)

- Atlantis

- Kompas

- Liternet (poetry, fiction, non-fiction: electronic and print)

- Обяви Варна[68] (free classifieds)

- Naroden Buditel (history)

- Slavena (history, children's books, travel, multimedia, advertising)

Local radio stations

- Alpha Radio

- DarikNews (Varna)

- FM+ Varna[22]

- Radio Bravo

- Radio Varna

Local TV stations

- BNT More

- TV Cherno more

- TV Varna

Web portals

- Varnaeye[69] (tourism, history, events and business)

- Varna Info (general info, English)

- Moreto.net (general info, news)

- chernomore.bg[70] (news agency)

- ida.bg[22] (general info, news)

- ole-bg[22] (sports)

- varna-sport.com (sports)

- Biznesa (business)

- Programata (free cultural guide)

- Parvi dubal (movies)

- Liternet (books)

- Varna na mladite (youth)

- Travel and accommodation guide (travel guide)

Hospitals

- Sveta Marina University Hospital for active treatment

- Sveta Anna Hospital for active treatment

- Navy Hospital

- Obstetrics and Gynecology Hospital

- Dr. Marko Markov Interdistrict Dispensary for Oncological Diseases[22]

- Sveta Petka Ophthalmology Clinic

- Kamee Clinic, plastic and reconstructive surgery

- Valem, plastic and aesthetic surgery

- Kibela Consultancy Centre, psychological consultancy

- Universum Medical, alternative medicine and massage

- Dentaprime Clinic, dental implants and aesthetic dentistry

Sports

Football is the biggest spectator sport with two rival clubs in the nation's top professional league, Cherno More (the Sailors), founded in 1913 and four times national champion, including the first championship in 1925, and Spartak (the Falcons), founded in 1918, one time champion and participant in the European Cup Winners' Cup in 1983, when it reached the second knockout round and played Manchester United F.C..

In the late 19th century, Varna was considered the birthplace of Bulgarian football with a Swiss gym teacher, Georges de Regibus, coaching the first varsity team at the men's high school. In February 2007, the city decided to replace its antiquated 1950's municipal stadium with a new arena according to UEFA/FIFA specifications.[71] The new venue will seat 30,000 (40,000 for concerts including standing room). Another state-of the-art track-and-field stadium with a capacity of 5,000 seats and training halls for professional and public use will open in the Mladost district in 2009 to compensate for the lost track-and-field capacity of old Varna stadium.[72]

Men's basketball (Euroins Cherno More), women's volleyball, gymnastics, boxing, martial arts, and sailing are also vibrant. The 4.5 km (2.8 mi) swimming marathon Cape Galata—Varna is a popular venue. Varna hosts international competitions, including world championships, and national events in several sports on a regular basis, including auto racing and motocross. Bulgarian national basketball and volleyball teams host their games, including FIVB Volleyball World League games, at the Palace of Culture and Sports, the country's largest arena.

Currently (2011), three 18-hole golf courses of professional quality have been constructed in the region to the north of the city in the vicinity of Balchik and Kavarna. These are Thracian Cliffs, Lighthouse Golf and Black Sea Rama. To the south of the city, Avren Golf Club[73] is due to be completed during 2012/13.

A kart racing track and a hippodrome with a horseback riding school is located in the Vinitsa neighborhood, and Asparuhov bridge is the foremost bungee jumping venue in the nation due to the local Club Adrenalin.[22] Another horse club is located just 10 minutes away from Varna in the nearby village of Kichevo.

In early August 2007, a new municipal sports complex with fields for football, basketball and volleyball was opened as a part of a larger complex of sports facilities, mini-golf, tennis, biking alleys, mini-lakes and ice-skating rinks in the district of Mladost. Smaller municipal fields opened in the Sea Garden, Asparuhov Val Park, and elsewhere; the municipal Olympic-size swimming pool complex was rebuilt also in 2007, and the first segment of a bike lane to connect the Sea Garden with the westernmost residential districts was completed outside City Hall.[74] Paying tribute to the golf course development mania, the mayor vowed to build a free municipal driving range in the district of Asparuhovo.[75] The new urban general plan (under discussion in early 2008) envisages a large public amateur sports complex south of Lake Varna[76] and a ski run with artificial snow covering.

The number and range of fitness, wellness and recreation clubs in Varna is rapidly growing, which reflects the positive change of lifestyle of the average Varna citizen.

Varna athletes won 4 of the 12 medals for Bulgaria at the 2004 Summer Olympics.

A recent addition to the cities sporting scene is cricket, which has been introduced by ex-pats from cricket playing nations.

Organized crime

Varna was rumored to be the hub for the Bulgarian organized crime. Some sectors of the economy, including gambling, corporate security, tourism, real estate, and professional sports, were believed to be controlled in part by business groups with links to Communist-era secret services or the military.

However, it is noted that in Varna, the so-called mutri (Mafia) presence was by no means as visible as it was in smaller coastal towns and resorts. Over the last couple of years, crime has subsided, which is said to have contributed to Varna being named as Bulgaria's Best City to Live In (2007);[26] in 2007, the regional police chief was promoted to the helm of the national police service.

International relations

Twin towns and sister cities

Varna is twinned with:

Aalborg, Denmark[77]

Aalborg, Denmark[77] Amsterdam, Netherlands

Amsterdam, Netherlands Aqaba, Jordan

Aqaba, Jordan Barcelona, Spain

Barcelona, Spain Boston, United States

Boston, United States Bayburt, Turkey

Bayburt, Turkey Dordrecht, Netherlands

Dordrecht, Netherlands Genoa, Italy

Genoa, Italy Hamburg, Germany

Hamburg, Germany Kavala, Greece

Kavala, Greece Kharkiv, Ukraine

Kharkiv, Ukraine Liverpool, United Kingdom

Liverpool, United Kingdom Malmö, Sweden[78]

Malmö, Sweden[78] Medellín, Colombia

Medellín, Colombia Memphis, United States

Memphis, United States Miami, United States

Miami, United States Novosibirsk, Russia

Novosibirsk, Russia Novorossiysk, Russia

Novorossiysk, Russia Odessa, Ukraine

Odessa, Ukraine Piraeus, Greece

Piraeus, Greece Rostock, Germany

Rostock, Germany Saint Petersburg, Russia

Saint Petersburg, Russia Sarandë, Albania

Sarandë, Albania Shëngjin, Albania

Shëngjin, Albania Stavanger, Norway

Stavanger, Norway Szeged, Hungary

Szeged, Hungary Turku, Finland

Turku, Finland Vysoké Mýto, Czech Republic

Vysoké Mýto, Czech Republic Washington, United Kingdom

Washington, United Kingdom Wels, Austria

Wels, Austria

Honour

Varna Peninsula on Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica is named after Varna.[79]

Varna, Illinois, a small town of 400 people, was named in this city's honour. The War of Varna was going on at the time.

The settlement and district centre of Varna in the Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia is named in commemoration of the taking of Varna by the Russian army during the 1828–1829 Russo-Turkish War.[80]

Varna Drive, in Toronto, Canada, is named after Varna.

Varna in fiction

Varna was Count Dracula's "transportation hub" — the point of origin of the ship Demeter and the initial destination of the Czarina Catherine — in Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula, and the place where the vampire's annihilation was planned to be carried out.[81]

British spy 07 kidnapped Soviet physicist Konstantin Trofimov from a villa in Varna in Andrei Gulyashki's novel Avakoum Zahov versus 07.

"The monastery at Varna" in the novel The Hills of Varna by Geoffrey Trease is a fictional place in the Balkans, not related to the real city.

An early mention of modern Varna in English literature is found in Charles Dickens' All the Year Round (Vol. 30) in 1873. Dickens visited the city as a war correspondent in the Crimean War in 1854.

See also

- List of airports in Bulgaria

- List of cities and towns in Bulgaria

- List of mayors of Varna

- St. Nikolai, Varna

References

- ↑ ,

- ↑ "Functional Urban Areas - Population on 1 January by age groups and sex". Eurostat. 1 April 2016. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

- ↑ "Варна (Varna) Becomes Centre of the Black Sea Euro-Region (Bulgarian)". Bg-news.org. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ Grande, Lance (2009). Gems and gemstones: Timeless natural beauty of the mineral world. The University of Chicago Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-226-30511-0. Retrieved 20 December 2011.

The oldest known gold jewelry in the world is from an archaeological site in Varna Necropolis, Bulgaria, and is over 6,000 years old (radiocarbon dated between 4,600BC and 4,200BC).

- ↑ "Monument of the Vikings to be built near Varna". bnews.bg.

- ↑ "w-r- The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition. 2000". Bartleby.com. Archived from the original on January 24, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Climatological Normals for Varna, Bulgaria (1952-2011)". Climatebase. Retrieved April 16, 2013.

- ↑ Borislav Petrov. "Ранновизантийската базилика". Varna.info.bg. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Standartnews Ltd. "Дървен град предхожда каменната Плиска" (in Bulgarian). Paper.standartnews.com. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ Apostolov, Shanko (Director, Władysław Warneńczyk Park Museum, Varna). "The Campaigns of Ladislaus of Varna and John Hunyadi in 1443–1444" (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ Kotzabassi, Maria. "Varna (Modern period)". Εγκυκλοπαίδεια Μείζονος Ελληνισμού. Retrieved 9 October 2011.

- ↑ BSH (1949-12-21). "The names of Varna". Varna.info.bg. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ ":-Община Варна-:". Varna.bg. Archived from the original on October 9, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Logistic Park Varna received First Class Investor Certificate – Daily News Article". Propertywisebulgaria.com. 2008-02-08. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Odessos Shipyard Varna". Odessos Shiprepair Yard. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Business". The Sofia Echo. 2007-04-23. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑

- ↑ "Business Park Varna – ONE STEP FORWARD". Bpv.bg. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "Money.bg – "Варна Тауърс" ООД взе отличие за топ – инвеститор". Money.ibox.bg. 2006-09-27. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Бизнес | Варна започва строителството на още един мол". Dnevnik.bg. 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

- ↑ "Dominus Home Page". Dominuss.com. Retrieved 2011-09-16.

- ↑ WebFX Studio. "Черно море – новините тогава, когато се случват". Chernomore.bg. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "SOUTHERN EUROPE – South-eastern city of the future: Varna, Bulgaria – Foreign Direct Investment (fDi)". Fdimagazine.com. 2004-08-09. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- 1 2 "Варна е най-добрият град за живеене в България – DARIK News". Dariknews.bg. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "CEEOL Balkan Studies, Issue 2 /2004". Ceeol.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ Georgi Gentchev. "varna sled 1876". Varna-bg.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ (Bulgarian)National Statistical Institute - 2012

- ↑ "General Directorate of Citizens' Registration and Administrative Services: Population Chart by permanent and tempoprary address (for provinces, municipalities and settlements) as of 15 September 2010" (in Bulgarian). Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "По неофициални данни населението на Варна е над 550 000 хиляди души". Moreto.net. 2010-01-14. Retrieved 2010-01-15.

- ↑ "Мрежа | Започва битката за детските градини | Общината: Не правете обсади, класирането ще е онлайн". Dnevnik.bg. 2007-12-27. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Varna, the City that Outran Statistics" (in Bulgarian). Dnevnik.bg. 2007-09-16. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Akcent newspaper home page".

- ↑ "Варна | Варна ще се застрои до Бяла, смята зам.-кмет". Moreto.net. 2008-02-22. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Варна | Кирил Йорданов: Във Варна живеят близо 1 милион. 60% са без варненска регистрация". Moreto.net. 2008-12-23. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- 1 2 "/ Weekend / House & Home – Port in a storm". Financial Times. 2009-01-17. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Национален статистически институт".

- ↑ "National Statistical Institute – Towns population 1956–1992 – in Bulgarian" (PDF). Statlib.nsi.bg:8181. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ WebDesign Ltd. www.webdesign-bg.eu. "Bulgarian National Statistical Institute – Bulgarian towns in 2009". Nsi.bg. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Bulgaria (Major Cities): Districts, Major Cities & Towns – Statistics & Maps on City Population". Citypopulation.de. 2011-12-31. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Cities of Bulgaria". Pop-stat.mashke.org. 2011-02-01. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Academy of Sciences -in Bulgarian" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Как дедите ни сложиха "български печат" на Варна". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ http://www.nsi.bg/ORPDOCS/Census2011_1.pop_by_age.xls

- ↑ http://www.nsi.bg/ORPDOCS/Census2011_4.pop_by_ethnos.xls

- ↑ http://www.strategy.bg/FileHandler.ashx?fileId=200

- ↑ ":-Община Варна-:". Varna.bg. Archived from the original on November 9, 2008. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ ":-Община Варна-:". Varna.bg. Archived from the original on April 25, 2009. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Окръжен съд Варна". Varna.court-bg.org. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ "Bulgaria – Embassies and Consulates". Embassypages.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ http://www.grao.bg/tna/tab02.txt

- ↑ http://moreto.net/novini.php?g=ОУП%20Варна

- ↑ Clark, Nick (2006-10-01). "Bulgaria: Get the party started – Europe, Travel – The Independent". The Independent. London. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Graffiti Festival Organized in Varna resort, Bulgaria". Beachbulgaria.com. 2006-05-26. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "In Pictures | Day in pictures". BBC News. 2006-02-01. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ http://auction-victoria.com/image.asp?image=4358

- ↑ http://catalog.libvar.bg/view/show_jpg_image.pl?MATERIAL=photo&image_id=67115563.401251512462638592429

- ↑ "TheShip – winner for best architect of 2005 for Vanya Karadjova". Varna Bulgaria Info.

- ↑ "Apollo Centre". The Sawyers Group, UK.

- ↑ http://www.varna-europa.com/

- ↑ Archived August 30, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "State Puppet Theatre Varna".

- 1 2 3 4 Yasen Kazandjiev. "- Scenderman - Artistic Network / Production / Management / Network -".

- ↑ http://www.dede-dessert.com/

- ↑ Kazandjiev, Yasen. "- Scenderman - Artistic Network / Production / Management / Network -". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "Труд". Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "O脚の原因と改善方法".

- ↑ "VARNAEYE.BG - EYE PRODUCT".

- ↑ "Черно море". CMP3.

- ↑ "Ńďîđňĺí Ęîěďëĺęń Âŕđíŕ". Sportcomplexvarna.com. Retrieved 2009-06-18.

- ↑ WebDesign Ltd. www.digitalentropia.com. "Нов лекоатлетически стадион "Младост" във Варна". Proactive-bg.eu. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Avren Golf Club". Avrengolf.com. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "Денят – Откриват първата велоалея във Варна – Стандарт". Standartnews.com. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ http://bg-golfer.net/index.php?option=com_smf&Itemid=66&topic=71.msg722#msg722. Retrieved February 9, 2008. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ WebFX Studio. "Черно море – новините тогава, когато се случват". Chernomore.bg. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

- ↑ "Aalborg Twin Towns". Europeprize.net. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "Vänorter" (in Swedish). Malmö stad. Retrieved 6 November 2013.

- ↑ http://apc.mfa.government.bg/

- ↑ Borislav Petrov. "Places around the world with the name of Varna". Varna.info.bg. Retrieved 2012-06-08.

- ↑ "25 – Dracula – Bram Stoker (1845–1912)". Classiclit.about.com. 2008-09-30. Retrieved 2009-05-06.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Varna. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Varna. |

- Official website (Bulgarian)

.jpg)