Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars sanctioned by the Latin Church between the 11th and 16th centuries, especially the campaigns in the Eastern Mediterranean with the aim of capturing Jerusalem from Islamic rule. Crusades were also fought for many other reasons such as to recapture Christian territory or defend Christians in non-Christian lands, resolve conflict among rival Roman Catholic groups, gain political or territorial advantage, or to combat paganism and heresy. The term crusade itself is modern, and has in more recent times been extended to include religiously motivated Christian military campaigns in the Late Middle Ages.

The First Crusade arose after a call to arms in a 1095 sermon by Pope Urban II. Urban urged military support for the Byzantine Empire and its Emperor, Alexios I, who needed reinforcements for his conflict with westward migrating Turks in Anatolia. Although one of Urban's stated aims was to guarantee pilgrims access to the holy sites in the Holy Land that were under Muslim control, scholars disagree whether this was the primary motivation for Urban or for the majority of those who heeded his call. Urban's wider strategy may have been to unite the Eastern and Western branches of Christendom, which had been divided since their split in the East–West Schism of 1054, and establish himself as head of the unified Church. Similarly, some of the hundreds of thousands of people who became crusaders by taking a public vow and receiving plenary indulgences from the church were peasants hoping for Apotheosis at Jerusalem, or forgiveness from God for all their sins. Others, historians argue, participated to satisfy feudal obligations, gain glory and honour, or find opportunities for economic and political gain. Regardless of the motivation, the response to Urban's preaching by people of many different classes across Western Europe established the precedent for later crusades.

Different perspectives of the actions carried out, at least nominally, under Papal authority during the crusades have polarised historians. To some their behaviour was incongruous with the stated aims and implied moral authority of the papacy and the crusades, in one case to the extent that the Pope excommunicated crusaders.[1] Crusaders often pillaged as they travelled, while their leaders retained control of much captured territory rather than returning it to the Byzantines. The People's Crusade included the Rhineland massacres: the murder of thousands of Jews. Constantinople was sacked during the Fourth Crusade, rendering the reunification of Christendom impossible.

The crusades had a profound impact on Western civilisation: they reopened the Mediterranean to commerce and travel (enabling Genoa and Venice to flourish); consolidated the collective identity of the Latin Church under papal leadership; and were a wellspring for accounts of heroism, chivalry and piety. These tales consequently galvanised medieval romance, philosophy and literature. The crusades also reinforced the connection between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism.

Terminology

_punish_Cretan_Saracens.jpg)

The term crusade is derived from a Middle Latin cruxata, cruciata. The adjective cruciatus had been used in the sense of "marked with a cross" from the 12th century; cruciatus (also cruxatus, croxatus, crucesignatus) was used of crusaders by the mid 13th century, from their practice of attaching a cloth cross symbol to their clothing. Use of cruxata (cruciata) for "crusade, military expedition against enemies of the church" is in use by the 1280s.[2] The French form croisade and Spanish cruzada are recorded by the 16th century.

The French form of the word first appears in its historiographical sense in the 17th century[3] and it was adopted into English and German in the 18th century.[4]

The Crusades in the Holy Land are traditionally counted as nine distinct campaigns, numbered from the First Crusade of 1095–99 to the Ninth Crusade of 1271/2. This convention is used by Charles Mills in his History of the Crusades for the Recovery and Possession of the Holy Land (1820), and is often retained for convenience, even though it is somewhat arbitrary: The Fifth and Sixth Crusades led by Frederick II may be considered a single campaign, as can the Eight Crusade and Ninth Crusade led by Louis IX.[5]

Usage of the term "crusade" may differ depending on the author. Constable (2001) describes four different perspectives among scholars:

- Traditionalists restrict their definition of crusades to the Christian campaigns in the Holy Land, "either to assist the Christians there or to liberate Jerusalem and the Holy Sepulcher", during 1095–1291.[6]

- Pluralists use the term crusade of any campaign explicitly sanctioned by the reigning Pope.[7] This reflects the view of the Roman Catholic Church (including medieval contemporaries such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux) that every military campaign given Papal sanction is equally valid as a crusade, regardless of its cause, justification, or geographic location. This broad definition subsumes attacks on paganism and heresy, such as the Albigensian Crusade, the Northern Crusades and the Hussite Wars, and wars for political or territorial advantage, such as the Aragonese Crusade in Sicily, a crusade declared by Pope Innocent III against Markward of Anweiler in 1202,[8] one against the Stedingers, several (declared by several popes) against Emperor Frederick II and his sons,[9] two crusades against opponents of King Henry III of England,[10] and the Christian re-conquest of Iberia.[11]

- Generalists see crusades as any and all holy wars connected with the Latin Church and fought in defence of their faith.

- Popularists[upper-alpha 1] limit the crusades to only those that were characterised by popular groundswells of religious fervour – that is, only the First Crusade and perhaps the People's Crusade.[12]

Background

In the seventh and eighth centuries, Islam was introduced in the Arabian Peninsula by the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a newly unified polity. This led to a rapid expansion of Arab power, the influence of which stretched from the northwest Indian subcontinent, across Central Asia, the Middle East, North Africa, southern Italy, and the Iberian Peninsula, to the Pyrenees.[13][14][15] Tolerance, trade, and political relationships between the Arabs and the Christian states of Europe waxed and waned. For example, the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah destroyed the Church of the Holy Sepulchre but his successor allowed the Byzantine Empire to rebuild it.[16] Pilgrimages by Catholics to sacred sites were permitted, resident Christians were given certain legal rights and protections under Dhimmi status, and interfaith marriages were not uncommon.[17] Cultures and creeds coexisted and competed, but the frontier conditions became increasingly inhospitable to Catholic pilgrims and merchants.[18]

The Reconquista (recapture of the Iberian Peninsula from the Muslims) began during the 8th century, reaching its turning point in 1085 when Alfonso VI of León and Castile retook Toledo from Muslim rule.[19] The Byzantine Empire also regained territory at the end of the 10th century, with Basil II spending most of his half-century reign in conquest. In Northern Europe, the Germans used crusading as a method to expand Christianity and their territories at the expense of the non-Christian Slavs,[20] and Sicily was conquered by Norman adventurer Roger De Hauteville in 1091.[21]

Europe in this period was immersed in power struggles on many different fronts. In 1054, centuries of attempts by the Latin Church to assert supremacy over the Patriarchs of the Eastern Empire led to a permanent division in the Christian church called the East–West Schism.[22] Following the Gregorian Reform an assertive, reformist papacy attempted to increase its power and influence. Beginning around 1075 and continuing during the First Crusade, the Investiture Controversy was a power struggle between Church and state in medieval Europe over whether the Catholic Church or the Holy Roman Empire held the right to appoint church officials and other clerics.[23][24] Antipope Clement III was an alternative pope for most of this period, and Pope Urban spent much of his early pontificate in exile from Rome. In this the papacy began to assert its independence from secular rulers, marshalling arguments for the proper use of armed force by Catholics. The result was intense piety, an interest in religious affairs, and religious propaganda advocating a just war to reclaim Palestine from the Muslims. The majority view was that non-Christians could not be forced to accept Christian baptism or be physically assaulted for having a different faith, although a minority believed that vengeance and forcible conversion were justified for the denial of Christian faith and government.[25] Participation in such a war was seen as a form of penance which could counterbalance sin.[26]

The status quo was disrupted by the western migrating Turks. In 1071 they defeated the Byzantine army at the Battle of Manzikert and the rapidly expanding Great Seljuk Empire gained nearly all of Anatolia while the empire descended into frequent civil wars.[27] One year later the Turks wrested control of Palestine from the Fatimids.[28] The disruption of pilgrimages by the Seljuk Turks prompted support for the crusades in Western Europe.[29]

History

First Crusade (1096–99) and immediate aftermath

In 1095 at the Council of Piacenza, Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos requested military aid from Pope Urban II to fight the Turks, probably in the form of mercenary reinforcements. It is also likely he exaggerated the danger facing the Eastern Empire while making his appeal.[30] At the Council of Clermont later that year, Urban raised the issue again and preached for a crusade. Historian Paul Everett Pierson asserts that Urban also hoped that aiding the Eastern Church would lead to its reunion with the Western under his leadership.[31]

Almost immediately thereafter Peter the Hermit began preaching to thousands of mostly poor Christians, whom he led out of Europe in what became known as the People's Crusade.[32] Peter had with him a letter he claimed had fallen from heaven instructing Christians to seize Jerusalem in anticipation of the apocalypse.[33] In addition to the motivations of the landed classes, academic Norman Cohn has identified a "messianism of the poor" inspired by an expected mass apotheosis at Jerusalem.[34] In Germany the Crusaders massacred Jewish communities. The Rhineland massacres were the first major outbreak of European Antisemitism.[35] In Speyer, Worms, Mainz and Cologne the range of anti-Jewish activity was broad, extending from limited, spontaneous violence to full-scale military attacks.[36] Despite Alexios advice to await the nobles the People's Crusade advanced to Nicaea and fell to a Turkish ambush at the Battle of Civetot, from which only about 3,000 crusaders escaped.[37]

Both Philip I, king of France and Henry IV, Holy Roman Emperor were in conflict with Urban and did not participate; the noble armies embarked in August and September 1096 divided into four separate parts.[38] The armies travelled eastward by land to Byzantium where they received a welcome from the Emperor.[39][40][41] The combined force including non-combatants may have contained as many as 100,000 people.[42] The army, mostly French and Norman knights under baronial leadership, pledged to restore lost territories to the empire and marched south through Anatolia.[43][44][45] The crusaders besieged Antioch, massacring the inhabitants and pillaging the city. They were immediately besieged by a large army led by Kerbogha. Bohemond of Taranto successfully rallied the crusader army and defeated Kerbogha.[46] Bohemond then kept control of the city, despite his pledge that he would provide aid to Alexios.[47] The remaining crusader army marched south along the coast reaching Jerusalem with only a fraction of their original forces.[48] The Jewish and Muslim inhabitants fought together to defend Jerusalem, but the crusaders entered the city on 15 July 1099. They proceeded to massacre the inhabitants and pillage the city.[49] In his Historia Francorum qui ceperunt Iherusalem, Raymond D'Aguilers exalted actions which would be considered atrocities from a modern viewpoint.[50]

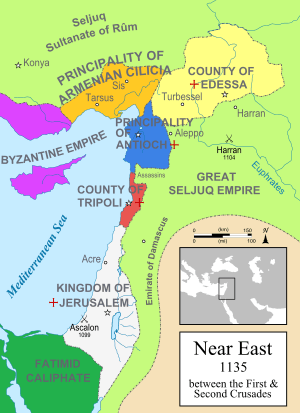

As a result of the First Crusade, four primary crusader states were created: the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the County of Edessa, the Principality of Antioch, and the County of Tripoli.[51] On a popular level, the First Crusade unleashed a wave of impassioned, pious Catholic fury which was expressed in the massacres of Jews that accompanied the crusades[52] and the violent treatment of the "schismatic" Orthodox Christians of the east.[53] A second, less successful crusade known as the Crusade of 1101 followed in which Turks led by Kilij Arslan defeated the crusaders in three separate battles.[54]

12th century

Under the papacies of Calixtus II, Honorius II, Eugenius III and Innocent II smaller scale crusading continued around the Crusader States in the early 12th century. There were campaigns by Fulk V of Anjou between 1120 and 1129, the Venetians in 1122–24, Conrad III of Germany in 1124 and the Knights Templar were established.[55] The period saw the innovation of granting indulgences to those who opposed papal enemies that marked the beginning of politically motivated crusades.[56] The loss of Aleppo in 1128 and Edessa (Urfa) in 1144 to Imad ad-Din Zengi, governor of Mosul led to preaching for what subsequently became known as the Second Crusade.[57][58][59] King Louis VII and Conrad III led armies from France and Germany to Jerusalem and also Damascus without winning any major victories.[60] Bernard of Clairvaux, who had encouraged the Second Crusade in his preaching, was upset with the violence and slaughter directed towards the Jewish population of the Rhineland.[61]

In the Iberian Peninsula crusaders continued to make gains with the king of Portugal, Afonso I, retaking Lisbon and Raymond Berenguer IV of Barcelona conquering the city of Tortosa[62][63] In Northern Europe the Saxons and Danes fought against Wends in the Wendish Crusade,[64] although no official papal bulls were issued authorising new crusades.[65] The Wends were finally defeated in 1162.[66]

In 1187 Saladin united the enemies of the Crusader States, was victorious at the Battle of Hattin and retook Jerusalem.[67][68] According to Benedict of Peterborough, Pope Urban III died of deep sadness on 19 October 1187 on hearing of the defeat.[69] His successor, Pope Gregory VIII, issued a papal bull named Audita tremendi that proposed a further crusade later numbered the third to recapture Jerusalem. Frederick I, Holy Roman Emperor died en route to Jerusalem, drowning in the Saleph River, and few of his men reached the Holy Land.[70]

Richard I of England conquered the island of Cyprus from the Byzantines in 1191 in response to his sister being taken prisoner by the island's ruler, Isaac Komnenos.[71] Richard then quarrelled with Philip II of France and Philip returned to France, leaving most of his forces behind. He then recaptured Acre after a long siege, travelled south along the Mediterranean coast, defeated the Muslims near Arsuf and recaptured the port city of Jaffa. Within sight of Jerusalem supply shortages forced them to retreat without taking the city.[72] A treaty was negotiated that allowed unarmed Catholics to make pilgrimages to Jerusalem and permitted merchants to trade.[73] Richard left, never to return, but Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor initiated the German Crusade to fulfil the promises made by his father, Frederick. Led by Conrad of Wittelsbach, Archbishop of Mainz the army captured the cities of Sidon and Beirut but after Henry died, most of the crusaders returned to Germany.[74]

13th century

Crusades in Northern Europe

Crusading became increasingly widespread in terms of geography and objectives during the 13th century. In Northern Europe the Catholic church continued to battle peoples whom they considered as pagans; Popes such as Celestine III, Innocent III, Honorius III and Gregory IX preached crusade against the Livonians, Prussians and Russia.[75][76]

When Pope Celestine III called for a crusade against Northern European pagans in 1193, Bishop Berthold of Hanover led a large army to defeat and his death in 1198. In response to the defeat, Pope Innocent III issued a papal bull declaring a crusade against the mostly pagan Livonians,[75] who were conquered and converted between 1202 and 1209.[77]

In the early 13th century Pope Honorius III declared a crusade against the Prussians.[76] Albert of Riga established Riga as the seat of the Bishopric of Riga and formed the Livonian Brothers of the Sword to convert the pagans to Catholicism and protect German commerce.[77] Konrad of Masovia gave Chelmno to the Teutonic Knights in 1226 as a base for crusade.[78] The Livonian Knights were defeated by the Lithuanians so Pope Gregory IX merged the remainder of the order into the Teutonic Order as the Livonian Order.[79] By the middle of the century the Teutonic Knights completed their conquest of the Old Prussians and went on to conquer and convert the Lithuanians in the subsequent decades.[80] The order was less successful in the Northern Crusades against Orthodox Russia, the Pskov Republic and the Novgorod Republic. In 1240 the Novgorod army defeated the Swedes in the Battle of the Neva, and two years later they defeated the Livonian Order in the Battle on the Ice.[81]

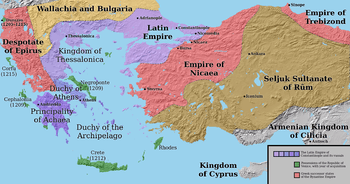

Fourth Crusade & aftermath

Innocent III also began preaching what became the Fourth Crusade in 1200, primarily in France, but also in England and Germany.[82] The Fourth Crusade never came to within 1,000 miles of its objective of Jerusalem, instead conquering Byzantium twice before being routed by the Bulgars at Adrianople. After gathering in Venice the crusade was used by Doge Enrico Dandolo and Philip of Swabia to further their secular ambitions. Dandolo's aim was expand Venice's power in the Eastern Mediterranean and Philip intended to restore his exiled nephew, Alexios IV Angelos, to the throne of Byzantium.[83] The crusaders were unable to pay the Venetians for a fleet when too few knights arrived in Venice, so they agreed to divert to Constantinople and share what could be looted as payment. As collateral the crusaders seized the Christian city of Zara; Innocent was appalled, and excommunicated them.[1] After the initial success in taking Byzantium, the original purpose of the campaign was defeated by the assassination of Alexios IV Angelos. In response the crusaders sacked the city, pillaged churches, and killed many citizens. The victors then divided the empire into Latin fiefs and Venetian colonies, resulting in two Roman Empires in the East: a Latin "Empire of the Straits" and an Empire of Nicea. In the long run, the sole beneficiary was Venice.[84]

Crusades in the Western Mediterranean

Innocent III launched the first crusade against heretics,[85] the Albigensian Crusade, against the Cathars in France and the County of Toulouse. Over the early decades of the century the Cathars were driven underground while the French monarchy asserted control over the region.[86] Andrew II of Hungary waged the Bosnian Crusade against the Bosnian church that was theologically Catholic but in long term schism with the Roman Catholic Church.[87] The conflict only ended with the Mongol invasion of Hungary in 1241. In the Iberian peninsula Crusader privileges were given to those aiding the Templars, Hospitallers and the Iberian orders that merged with the Order of Calatrava and the Order of Santiago. The papacy declared frequent Iberian crusades and from 1212 to 1265, and the Christian kingdoms drove the Muslims back to the Emirate of Granada, which held out until 1492 when the Muslims and Jews were expelled from the peninsula.[88]

Further Eastern Crusades

Crusading resumed against Saladin's Ayyubid successors in Egypt and Syria in 1217, following Innocent III's Fourth Council of the Lateran. Led by Andrew II and Leopold VI, Duke of Austria, forces drawn mainly from Hungary, Germany, Flanders, and Frisia achieved little. Leopold and John of Brienne besieged and captured Damietta but an invasion further into Egypt was compelled to surrender.[89][90] Damietta was returned and an eight-year truce agreed.[91] Emperor Frederick II, who had been excommunicated for breaking his vow to crusade, finally arrived at Acre in 1228.[92][93] A peace treaty was agreed giving Latin Christians most of Jerusalem and a strip of territory from Acre, while the Muslims controlled their sacred areas. In return, an alliance was made with Al-Kamil, Sultan of Egypt, against all of his enemies of whatever religion.[94] After the truce expired, further campaigns were led by Theobald I of Navarre, Peter of Dreux and Hugh IV, Duke of Burgundy. Defeated at Gaza, Theobald agreed treaties with Damascus and Egypt that returned territory to the crusader states. He returned to Europe in 1240 but Richard of Cornwall arrived in Acre a few weeks later and completed the enforcement.[95]

In 1244 a band of Khwarezmian mercenaries travelling to Egypt captured Jerusalem en-route and defeated a combined Christian and Syrian army at the La Forbie.[96] In response Louis IX of France organised a crusade to attack Egypt, arriving in 1249.[97] This was not a success. Louis was defeated at Mansura and captured as he retreated back to Damietta.[98] Another truce was agreed for a ten-year period and Louis was ransomed. Louis remained in Syria until 1254 to consolidate the Crusader states.[99] From 1265 to 1271, Baibars drove the Franks to a few small coastal outposts.[100]

Crusading Division

The Crusader states were not unified and various powers competed for influence. In 1256 Genoa and Venice went to war over territory in Acre and Tyre.[101] Venice conquered the disputed territory but was unable to expel the Genoese. Two factions embarked on a 14-month siege: on one side was Genoa, Philip of Monfort, John of Arsuf and the Knights Hospitaller; the other was Venice, the Count of Jaffa and the Knights Templar.[102] After the Genoese were expelled in 1261, Pope Urban IV brokered a peace to support the defence against the Mongols.[103] Conflict resumed in 1264 with the Genoese now supported by Michael VIII Palaiologos, Emperor of Nicaea the Egyptian sultan Baibars.[104] Both sides used Muslim soldiers, particularly Turcopoles. The war significantly weakened the kingdom with most fortified buildings in Acre destroyed. According to contemporary reports 20,000 men died in the conflict. Genoa finally regained its quarter in Acre in 1288.[105]

The French, led by Louis IX's brother Charles of Anjou, similarly sought to expand their influence. In 1266, he seized Sicily, parts of the eastern Adriatic, Corfu, Butrinto, Avlona, and Suboto. He attempted to gain Byzantium politically through the Treaty of Viterbo. The heirs of Baldwin II of Constantinople and William II Villehardouin married Charles' children. If there were no offspring Charles would receive the empire and principality. Charles executed Conradin, great-grandson of Isabella I of Jerusalem and principal pretender to the throne of Jerusalem, when he seized Sicily from the Holy Roman Empire. When he purchased the rights to Jerusalem from Maria of Antioch, the surviving grandchild of Queen Isabella, he created a claim to rival that of Isabella's great grandson, Hugh III of Cyprus. Charles' planned crusade to restore the Latin Empire alarmed Michael VIII Palailogos. He delayed Charles by beginning negotiations with Pope Gregory X for union of the Greek and the Latin churches with Charles and Philip of Courtenay compelled to form a truce with Byzantium. Michael also provided Genoa with funds to encourage revolt in Charles' northern Italian territories.[106]

In 1270, Charles turned his brother King Louis IX's last crusade to his own advantage, persuading Louis to ignore his advisers and direct the Eighth Crusade against Charles' rebel Arab vassals in Tunis. Louis' army was devastated by disease in the hot-summer Mediterranean climate, and Louis himself died at Tunis on 25 August. This ended the last significant attempt to take the Holy Land.[107]

The 1281 election of a French pope, Martin IV, brought the full power of the papacy into line behind Charles. He prepared to launch a crusade with 400 ships carrying 27,000 mounted knights against Constantinople. But the fleet was destroyed in an uprising fomented by Michael VIII Palailogos and Peter III of Aragon. Peter was proclaimed king, and the House of Charles of Anjou was exiled from Sicily. Martin excommunicated Peter and called for a crusade against Aragon before Charles died in 1285, allowing Henry II of Cyprus to reclaim Jerusalem. Charles had spent his life trying to amass a Mediterranean empire, and he and Louis saw themselves as God's instruments to uphold the papacy.[108]

One factor in the crusaders' decline was the disunity and conflict among Latin Christian interests in the eastern Mediterranean. Martin compromised the papacy by supporting Charles of Anjou, and tarnished its spiritual lustre with botched secular "crusades" against Sicily and Aragon. The collapse of the papacy's moral authority and the rise of nationalism rang the death knell for crusading, ultimately leading to the Avignon Papacy and the Western Schism. The mainland Crusader states of the outremer were extinguished with the fall of Tripoli in 1289 and Acre in 1291.[109] Most remaining Latin Christians left for destinations in the Frankokratia or were killed or enslaved.[110]

14th and 15th centuries

Minor crusading efforts lingered into the 14th century; Peter I of Cyprus captured and sacked Alexandria in 1365 in what became known as the Alexandrian Crusade; his motivation was as much commercial as religious.[111] Louis II led the 1390 Barbary Crusade against Muslim pirates in North Africa; after a ten-week siege, the crusaders signed a ten-year truce.[112]

Several crusades were launched during the 14th and 15th centuries to counter the expansion of the Ottoman Empire. The first, in 1396, was led by Sigismund of Luxemburg, king of Hungary; many French nobles joined Sigismund's forces, including the crusade's military leader, John the Fearless (son of the Duke of Burgundy). Sigismund advised the crusaders to focus on defence when they reached the Danube, but they besieged the city of Nicopolis. The Ottomans defeated them in the Battle of Nicopolis on 25 September, capturing 3,000 prisoners.[113]

The Hussite Wars, also known as the "Hussite Crusade", involved military action against the Bohemian Reformation in the Kingdom of Bohemia and the followers of early Czech church reformer Jan Hus, who was burned at the stake in 1415. Crusades were declared five times during that period: in 1420, 1421, 1422, 1427, and 1431. These expeditions forced the Hussite forces, who disagreed on many doctrinal points, to unite to drive out the invaders. The wars ended in 1436 with the ratification of the compromise Compacts of Basel by the Church and the Hussites.[114]

Polish-Hungarian King Władysław Warneńczyk invaded the recently conquered Ottoman territory, reaching Belgrade in January 1444; a negotiated truce was repudiated by Sultan Murad II within days of its ratification. Further efforts by the crusaders ended in the Battle of Varna on 10 November, a decisive Ottoman victory which led to the withdrawal of the crusaders. This withdrawal, following the last Western attempt to aid the Byzantine Empire, led to the 1453 fall of Constantinople. John Hunyadi and Giovanni da Capistrano organised a 1456 crusade to lift the Ottomon siege of Belgrade.[115] In April 1487, Pope Innocent VIII called for a crusade against the Waldensians of Savoy, the Piedmont, and the Dauphiné in southern France and northern Italy. The only efforts undertaken were in the Dauphiné, resulting in little change.[116]

Crusader states

The First Crusade established the first four crusader states in the Eastern Mediterranean: the County of Edessa (1098–1149), the Principality of Antioch (1098–1268), the Kingdom of Jerusalem (1099–1291), and the County of Tripoli (1104—Tripoli was not conquered until 1109—to 1289). The Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia originated before the Crusades, but it received kingdom status from Pope Innocent III and later became fully Westernised by the House of Lusignan. According to historian Jonathan Riley-Smith, these states were the first examples of "Europe overseas". They are generally known as outremer, from the French outre-mer ("overseas" in English).[117]

The Fourth Crusade established a Latin Empire in the east and allowed the partition of Byzantine territory by its participants. The Latin emperor controlled one-fourth of the Byzantine territory, Venice three-eighths (including three-eighths of the city of Constantinople), and the remainder was divided among the other crusade leaders. This began the period of Greek history known as Frankokratia or Latinokratia ("Frankish [or Latin] rule"), when Catholic Western European nobles—primarily from France and Italy—established states on former Byzantine territory and ruled over the Orthodox Byzantine Greeks.[118][upper-alpha 2]

Finance

Crusades were expensive; as the number of wars increased, their costs escalated. Pope Urban II called upon the rich to help First Crusade lords such as Duke Robert of Normandy and Count Raymond of St. Gilles, who subsidised knights in their armies. The total cost to King Louis IX of France of the 1284–85 crusades was estimated at six times the king's annual income. Rulers demanded subsidies from their subjects,[119] and alms and bequests prompted by the conquest of Palestine were additional sources of income. The popes ordered that collection boxes be placed in churches and, beginning in the mid-twelfth century, granted indulgences in exchange for donations and bequests.[120]

Military orders

The military orders, especially the Knights Hospitallers and the Knights Templars, played a major role in providing support for the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem and the other Crusader states, providing decisive forces of highly trained and motivated soldiers at critical moments.[121] The Hospitallers and the Templars became international organisations with depots beyond the Levant, spreading across Europe. The Teutonic Knights and the Livonian Brothers of the Sword focused on the Baltic. The Order of Santiago, Order of Calatrava, Order of Alcántara, and Order of Montesa concentrated on the Iberian Peninsula and its Reconquista.

The Knights Hospitallers (Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem) had been founded in Jerusalem before the First Crusade but greatly enlarged its mission once the Crusades began.[122] After the fall of Acre they relocated to Cyprus, conquering and ruling Rhodes (1309–1522) and Malta (1530–1798). The Poor Knights of Christ and its Temple of Solomon were founded in 1118 to protect pilgrims en route to Jerusalem. They became wealthy and powerful through banking and real estate. In 1322 the king of France suppressed the Knights Templar, ostensibly for sodomy, magic and heresy, but probably for financial and political reasons.[123] Regional remains of the order was merged with the Knights Hospitallers and other military orders.

Other than that, original medieval military orders persists until this day, in modern organisations with modified charters.

Society and gender

Women were intimately connected to the Crusades; they aided in recruitment, took over the crusaders' responsibilities in their absence, and provided financial and moral support.[124][125] Historians contend that the most significant role played by women in the West was in maintaining the status quo.[126] Landholders left for the Holy Land, leaving control of their estates to regents who were often wives or mothers. Since the Church recognised that risk to families and estates might discourage crusaders, special papal protection was a crusading privilege.[127] Some aristocratic women participated in crusades, such as Eleanor of Aquitaine (who joined her husband, Louis VII).[128] Non-aristocratic women also served in positions such as washerwomen.[126] When Christian women fought in battle (counter to assumptions about feminine nature), their role was more controversial; accounts of female warriors were primarily recorded by Muslim historians, who portrayed these women as barbarous and ungodly characters.[129] James Illston concludes:

- despite theories and laws which excluded women from war, women could and did make effective military leaders, fulfill important support roles, and become the victims of wartime aggression and violence. The importance of women's roles may have been noted rarely in contemporary writings and intellectual debates, but this lack of recognition does not take away from the fact that women in Western European society were integral to the planning, execution, and impact of war.[130]

The Children's Crusade was said to have been a Catholic movement in France and Germany in 1212 that tried to reach the Holy Land. The traditional narrative is probably conflated from some factual and mythical notions of the period including visions by a French or German boy, an intention to peacefully convert Muslims in the Holy Land to Christianity, a band of several thousand youths set out for Italy, and children being sold into slavery.[131] A study published in 1977 casts doubt on the existence of these events, and many historians came to believe that they were not (or not primarily) children but multiple bands of "wandering poor" in Germany and France, some of whom tried to reach the Holy Land and others who never intended to do so.[132][133][134][135]

Three crusading efforts were made by peasants during the mid-1250s and the early 14th century. The first, the Shepherds' Crusade of 1251, was preached in northern France. After a meeting with Blanche of Castile, it became disorganised and was disbanded by the government.[136] The second, in 1309, occurred in England, northeastern France, and Germany; as many as 30,000 peasants arrived at Avignon before it was disbanded.[137] The third, in 1320, became a series of attacks on clergy and Jews and was forcibly suppressed.[138] This "crusade" is primarily seen as a revolt against the French monarchy. The Jews had been allowed to return to France, after being expelled in 1306; any debts owed to the Jews before their expulsion were collected by the monarchy.[139]

Legacy

According to Jonathan Riley-Smith the kingdom of Jerusalem was the first experiment in European colonialism creating a 'Europe Overseas' or Outremer.[83] The raising, transportation and supply of large armies led to flourishing trade between Europe and the outremer. The Italian city states of Genoa and Venice flourished, creating profitable trading colonies in the eastern Mediterranean.[140] This trade was sustained through the middle Byzantine and Ottoman eras and the communities were often assimilated to be known as Levantines or Franco-Levantines.[upper-alpha 3][142]

The Crusades consolidated the papal leadership of the Latin Church, reinforcing the link between Western Christendom, feudalism and militarism manifesting itself in the habituating of the clergy to violence.[83] This led to the legitimisation of seizing land and possessions from pagans on religious grounds and was debated through to the Age of Discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries.[143] In addition the growth of the system of indulgences later was a catalyst for the Protestant Reformation in the early 16th century.[144] The crusades also had a role in the creation and institutionalisation of the military and Dominican orders as well as the Medieval Inquisition.[145]

This assertiveness and the behaviour of the crusaders appalled the Greeks and Muslims providing a lasting barrier between the Latin world and both the Islamic and Orthodox religions. This made the reunification of the Christian church impossible and created a perception of the Westerners of being both aggressors and losers.[83]

Helen Nicholson argues that the increased contact between cultures the Crusades instigated improved the perception of Islamic culture.[146] Alongside contact in Sicily and Spain the crusades led to knowledge exchange with Christians learning new ideas from the Muslims in literature and hygiene. The Muslims also had classical Greek and Roman texts in their libraries, allowing Europe to rediscover pre-Christian philosophy.[147] In contrast the Muslim world took little from the Crusaders beyond military tactics and did not take any real interest in European culture until the 16th century. Indeed, the Crusades were of little interest to the Muslim world: there was no history of the crusades translated into Arabic until 1865 and no published work by a Muslim until 1899.[148]

Jonathan Riley-Smith considers that much of the popular understanding of the crusades derives from the novels of Walter Scott and the French histories by Joseph François Michaud. The crusades provided an enormous amount of source material, stories of heroism and interest that underpinned growth in medieval literature, romance and philosophy.[83]

Historiography

Five major sources of information exist on the Council of Clermont that led to the First Crusade: the anonymous Gesta Francorum (The Deeds of the Franks, dated about 1100–01); Fulcher of Chartres, who attended the council; Robert the Monk, who may have been present, and the absent Baldric, archbishop of Dol and Guibert de Nogent. These retrospective accounts differ greatly.[149] In his 1106–07 Historia Iherosolimitana, Robert the Monk wrote that Urban asked western Roman Catholic Christians to aid the Orthodox Byzantine Empire because "Deus vult" ("God wills it") and promised absolution to participants; according to other sources, the pope promised an indulgence. In these accounts, Urban emphasises reconquering the Holy Land more than aiding the emperor and lists gruesome offences allegedly committed by Muslims. Urban wrote to those "waiting in Flanders" that the Turks, in addition to ravaging the "churches of God in the eastern regions", seized "the Holy City of Christ, embellished by his passion and resurrection—and blasphemy to say it—have sold her and her churches into abominable slavery". Although the pope did not explicitly call for the reconquest of Jerusalem, he called for military "liberation" of the Eastern Churches.[150] After the 1291 fall of Acre, European support for the Crusades continued despite criticism by contemporaries, such as Roger Bacon, who believed them ineffective: "Those who survive, together with their children, are more and more embittered against the Christian faith".[151]

During the 16th-century Reformation and Counter-Reformation, Western historians saw the crusades through the lens of their own religious beliefs. Protestants saw them as a manifestation of the evils of the papacy, and Catholics viewed them as forces for good.[152] Eighteenth-century Enlightenment historians tended to view the Middle Ages in general, and the crusades in particular, as the efforts of barbarian cultures driven by fanaticism.[153] These scholars expressed moral outrage at the conduct of the crusaders and criticised the crusades' misdirection—that of the Fourth in particular, which attacked a Christian power (the Byzantine Empire) instead of Islam. The Fourth Crusade had resulted in the sacking of Constantinople, effectively ending any chance of reconciling the East–West Schism and leading to the fall of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottomans. In The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire Edward Gibbon wrote that the crusaders' efforts could have been more profitably directed towards improving their own countries.[5] By the early Romantic period in the 19th century, that harsh view of the Crusades and their era had softened;[154] scholarship later in the century emphasised specialisation and detail.[155]

The 20th century produced three important histories of the crusades: by Steven Runciman, Rene Grousset and a multi-author work edited by K. M. Stetton.[156] Historians in this period often echoed Enlightenment-era criticism: Runciman wrote during the 1950s, "High ideals were besmirched by cruelty and greed ... the Holy War was nothing more than a long act of intolerance in the name of God".[118] According to Norman Davies, the crusades contradicted the Peace and Truce of God supported by Urban and reinforced the connection between Western Christendom, feudalism, and militarism. The formation of military religious orders scandalised the Orthodox Byzantines, and crusaders pillaged countries they crossed on their journey east. Violating their oath to restore land to the Byzantines, they often kept the land for themselves.[157][158] David Nicolle called the Fourth Crusade controversial in its "betrayal" of Byzantium.[159] Similarly, Norman Housley viewed the persecution of Jews in the First Crusade—a pogrom in the Rhineland and the massacre of thousands of Jews in Central Europe—as part of the long history of anti-Semitism in Europe.[160]

See also

- Crusade cycle - Old French cycle of epic poems concerning the First Crusade

- List of principal Crusaders

- Minor Crusades

- Alexandrian Crusade (1365)

- Savoyard Crusade (1366–67)

- List of Crusader castles

- Art of the Crusades

- History of the Jews and the Crusades

- Jihad and jihadism

- Miles Christianus, lit. "Christian soldier" - Christian concept of a "soldier of Christ"

- Milkhemet Mitzvah - Hebrew Bible concept of righteous, religiously ordained war

- Religious war

Footnotes

- ↑ Constable did not use this term; see Nicholson 2004, p. x

- ↑ The Partitio terrarum imperii Romaniae is a valuable record of early-13th-century Byzantine administrative divisions (episkepsis) and family estates.

- ↑ (Frankolevantini; French Levantins, Italian Levantini, Greek Φραγκολεβαντίνοι, and Turkish Levantenler or Tatlısu Frenk leri). The term "Levantine" was used pejoratively for inhabitants of mixed Arab and European descent and for Europeans who adopted local dress and customs.[141]

References

- 1 2 Lock 2006, pp. 158–159

- ↑ The main meaning of cruciatus is "tormented" (participle of crucio); the meaning "marked by a cross" and "crusader; crusade" is often spelled with x in Middle Latin. Mittellateinisches Wörterbuch vol. 2 (1999), s.v. "cruciatus": Annales Ianuenses. II p. 124,16 rex Aragonensis cum maxima multitudine militum et peditum et cum multis croxatis ... Yspaniam intraverunt. Annales Placentini Gibellini a. 1270 p. 549,41 facta pactione cum rege Tunicano et gente Saracena et vendita cruxata pro peccunia. a. 1284 p. 579, 19 ordinavit et statuit papa magnam cruxatam per christianos, ita quod generaliter predicatur ... ubique magna cruxata contra eum (sc. regem Aragonensem). Charles du Fresne, sieur du Cange, Glossarium mediae et infimae latinitatis, éd. augm., Niort : L. Favre, 1883‑1887, t. 2, col. 629a, s.v. "Cruciatæ" (Expeditiones sacræ contra Saracenos et Hæreticos, quod, qui iis sese adjungerent, Crucis signum in vestibus deferrent) references the use of the Latin term in the 14th and 15th centuries. Occurrit non semel apud Will. Thorn. et apud Ericum Upsaliensem lib. 3. Hist. Suecor. ann. 1292. ubi Loccenius, nescio quam historiam de Cruce Christi somniat

- ↑ L'Histoire des Croisades by Archange de Clermont OFM in Traité du Calvaire de Hiérusalem et de Dauphiné, Lyon (1638).

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 258. The first recorded use of the term in English was by William Shenstone in 1757.Hindley 2004, pp. 2–3

- 1 2 Davies 1997, p. 358

- ↑ Constable 2001, p. 12

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2009, p. 27

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 255–256

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 172–180

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 167

- ↑ Davies 1997, pp. 362–364

- ↑ Constable 2001, pp. 12&ndas;15

- ↑ Wickham 2009, p. 280

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 4

- ↑ Hindley 2004, p. 14

- ↑ Pringle 1999, p. 157

- ↑ Findley 2005, p. 73

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 15–16

- ↑ Bull 1999, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Housley 2006, p. 31

- ↑ Mayer 1988, pp. 17–18

- ↑ Mayer 1988, pp. 2–3

- ↑ Rubenstein 2011, p. 18

- ↑ Cantor 1958, pp. 8–9

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2009, pp. 10–11

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 8–10

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, p. 97

- ↑ Hindley 2004, p. 15

- ↑ Tolan, Veinstein & Henry 2013, p. 37

- ↑ Mayer 1988, pp. 6–7

- ↑ Pierson 2009, p. 103

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Slack 2013, pp. 228–230

- ↑ Cohn 1970, pp. 61, 64

- ↑ Slack 2013, pp. 108–109

- ↑ Chazan 1996, p. 60

- ↑ Hindley 2004, p. 23

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 106–110

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 27–30

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 30–31

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, pp. 50–52

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, p. 46

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 32–36

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 143–146

- ↑ Mayer 1988, pp. 60–61

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 146–153

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 156–158

- ↑ Sinclair 1995, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 50–51

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 23–24

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 192–194

- ↑ Housley 2006, p. 42

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 144–145

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 146–147

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 144

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 71–74

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 77–85

- ↑ Hindley 2004, p. 77

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 75–77

- ↑ Villegas-Aristizabal 2009, pp. 63–129

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 148

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 213

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 55–56

- ↑ Holt 1983, pp. 235–239

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, pp. 343–357

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, p. 367

- ↑ Tyerman 2007, pp. 35–36

- ↑ Flori 1999, p. 132

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 151–154

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, pp. 512–513

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 155

- 1 2 Lock 2006, p. 82

- 1 2 Lock 2006, p. 92

- 1 2 Lock 2006, p. 84

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 96

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 103

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 221–222

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 104, 221

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 502–508

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davies 1997, pp. 359–360

- ↑ Davies 1997, p. 360

- ↑ Riley-Smith 1999, p. 4

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 163–165

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 172–173

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 211

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 168–169

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2005, pp. 179–180

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 561–562

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 169

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, pp. 566–568

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, p. 569

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 173–174

- ↑ Asbridge 2011, pp. 574–576

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 770–775

- ↑ Hindley 2004, pp. 194–195

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 178

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 816–817

- ↑ Marshall 1994, p. 39

- ↑ Marshall 1994, p. 10

- ↑ Riley-Smith 1973, p. 37

- ↑ Marshall 1994, p. 59

- ↑ Marshall 1994, p. 41

- ↑ Baldwin 2014

- ↑ Strayer 1969, p. 487

- ↑ Setton 1985, p. 201

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 122

- ↑ Tyerman 2006, pp. 820–822

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 195–196

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 199

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 200

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 201–202

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 202–203

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 204

- ↑ "Outremer". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- 1 2 Runciman 1951, p. 480

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2009, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Riley-Smith 2009, p. 44

- ↑ Andrea 2003, pp. 213–15

- ↑ Nicholson 2001

- ↑ Davies 1997, p. 359

- ↑ Hodgson 2007, pp. 39–44

- ↑ Maier 2004, pp. 61–82

- 1 2 EdingtonLambert 2002, p. 98

- ↑ Hodgson 2007, pp. 110–112

- ↑ Owen 1993, p. 22

- ↑ Nicholson 1997, p. 337

- ↑ James Michael Illston, "'An Entirely Masculine Activity'? Women and War in the High and Late Middle Ages Reconsidered," (Thesis, Department of History, University of Canterbury, 2009) p. 110.

- ↑ Zacour 1969, pp. 325–342

- ↑ Raedts 1977, pp. 279–323

- ↑ Russell, Oswald, "Children's Crusade", Dictionary of the Middle Ages , 1989

- ↑ Bridge 1980

- ↑ Miccoli 1961, pp. 407–443

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 179

- ↑ Lock 2006, pp. 187–188

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 190

- ↑ Tuchman 2011, p. 41

- ↑ Housley 2006, pp. 152–154

- ↑ "Levantine". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Krey 2012, pp. 280–281

- ↑ Housley 2006, pp. 146–147

- ↑ Housley 2006, pp. 147–149

- ↑ Strayer 1992, p. 143

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, p. 96

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, pp. 93–94

- ↑ Nicholson 2004, p. 95

- ↑ Strack 2012, pp. 30–45

- ↑ Riley-Smith & Riley-Smith 1981, p. 38

- ↑ Rose 2009, p. 72

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 257

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 259

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 261

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 266

- ↑ Lock 2006, p. 269

- ↑ Kolbaba 2000, p. 49

- ↑ Vasilev 1952, p. 408

- ↑ Nicolle 2011, p. 5

- ↑ Housley 2006, pp. 161–163

Bibliography

- Andrea, Alfred J. (2003). Encyclopedia of the Crusades. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-31659-3. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Asbridge, Thomas (2011). The Crusades: The Authoritative History of the War for the Holy Land. Ecco. ISBN 978-0-06-078729-5.

- Baldwin, Philip B. (2014). 'Pope Gregory X and the crusades'. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84383-916-3.

- Bridge, Antony (1980). The Crusades. London: Granada Publishing. ISBN 0-531-09872-9.

- Bull, Marcus (1999). "Origins". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Cantor, Norman F (1958). Church. Kingship, and Lay Investiture in England: 1089–1135. Princeton University Press..

- Chazan, Robert (1996). European Jewry and the First Crusade. U. of California Press. p. 60. ISBN 978-0-520-91776-7. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Cohn, Norman (1970). The pursuit of the Millennium.

- Constable, Giles (2001). "The Historiography of the Crusades". In Laiou, Angeliki E.; Mottahedeh, Roy P. The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World. Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 1–22. ISBN 978-0-88402-277-0. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Daniel, Norman (1979). The Arabs and Mediaeval Europe. Longman Group Limited. ISBN 0-582-78088-8.

- Davies, Norman (1997). Europe – A History. Pimlico. ISBN 0-7126-6633-8.

- Edington, Susan B.; Lambert, Sarah (2002). Gendering the Crusades. Columbia University Press.

- Findley, Carter Vaughan (2005). The Turks in World History. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-516770-8.

- Flori, Jean (1999), Richard Coeur de Lion: le roi-chevalier (in French), Paris: Biographie Payot, ISBN 978-2-228-89272-8

- Hindley, Geoffrey (2004). The Crusades: Islam and Christianity in the Struggle for World Supremacy. Carrol & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1344-5.

- Hodgson, Natasha (2007). Women, Crusading and the Holy Land in Historical Narrative. Boydell.

- Holt, P. M. (1983). "Saladin and His Admirers: A Biographical Reassessment". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 46 (2): 235–239. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00078824. JSTOR 615389.

- Housley, Norman (2006). Contesting the Crusades. Blackwell Publishing. ASIN 1405111895. ISBN 1-4051-1189-5.

- Kahf, Mohja (1999). Western Representations of the Muslim Women: From Termagant to Odalisque. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-74337-3.

- Kolbaba, T. M. (2000). The Byzantine Lists: Errors of the Latins. University of Illinois.

- Krey, August C. (2012). The First Crusade: The Accounts of Eye-Witnesses and Participants. Arx Publishing. ISBN 978-1-935228-08-0.

- Lock, Peter (2006). Routledge Companion to the Crusades. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-39312-4.

- Maier, Christoph T. (March 2004). "The roles of women in the crusade movement: a survey". Journal of medieval history. 30 (1): 61–82. doi:10.1016/j.jmedhist.2003.12.003.

- Marshall, Christopher (1994). Warfare in the Latin East, 1192–1291. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47742-0.

- Mayer, Hans Eberhard (1988). The Crusades (Second ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-873097-7.

- Miccoli, Giovanni (1961). "La crociata dei fancifulli". Studi medievali. Third Series.

- Nicholson, Helen (1997). "Women on the Third Crusade". Journal of Medieval History. 23 (4): 335. doi:10.1016/S0304-4181(97)00013-4.

- Nicholson, Helen J. (2001). The Knights Hospitaller. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-0-85115-845-7. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Nicholson, Helen (2004). The Crusades. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32685-1.

- Nicolle, David (2011). The Fourth Crusade 1202–04: The Betrayal of Byzantium. Osprey Publishing.

- Owen, Roy Douglas Davis (1993). Eleanor of Aquitaine: Queen and Legend. Blackwell Publishing.

- Pierson, Paul Everett (2009). The Dynamics of Christian Mission: History Through a Missiological Perspective. WCIU Press. ISBN 978-0-86585-006-4. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Pringle, Denys (1999). "Architecture in Latin East". In Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Raedts, P. (1977). "The Children's Crusade of 1213". Journal of Medieval History. 3 (4): 279. doi:10.1016/0304-4181(77)90026-4.

- Retso, Jan (2003). The Arabs in Antiquity: Their History from the Assyrians to the Umayyads. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-7007-1679-1.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1973). The Feudal Nobility and the Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1174–1277. Archon Books. ISBN 978-0-208-01348-4.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1999). Riley-Smith, Jonathan, ed. The Crusading Movement and Historians. The Oxford History of the Crusades. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280312-3.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2005). The Crusades: A Short History (Second ed.). Yale University Press. ISBN 0-300-10128-7.

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan (2009). What Were the Crusades?. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-22069-0.

- Riley-Smith, Louise; Riley-Smith, Jonathan (1981). The Crusades: Idea and Reality, 1095–1274. Documents of Medieval History. 4. E. Arnold. ISBN 0-7131-6348-8.

- Rose, Karen (2009). The Order of the Knights Templar.

- Rubenstein, Jay (2011). Armies of Heaven: The First Crusade and the Quest for Apocalypse. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-01929-3.

- Runciman, Steven (1951). A History of the Crusades: The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades (reprinted 1987 ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Setton, Kenneth M. (1985). A History of the Crusades: The Impact of the Crusades on the Near East. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 0-299-09144-9.

- Sinclair, Andrew (1995). Jerusalem: The Endless Crusade. Crown Publishers.

- Slack, Corliss K (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Crusades. Scarecrow Press. pp. 108–09. ISBN 978-0-8108-7831-0. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Strack, Georg (2012). "The Sermon of Urban II in Clermont and the Tradition of Papal Oratory" (PDF). Medieval Sermon Studies. 56 (30#1): 30–45. doi:10.1179/1366069112Z.0000000002.

- Strayer, Joseph R. (1969). "The Crusades of Louis IX". In Wolff, R. L.; Hazard, H. W. The Later Crusades, 1189–1311. pp. 487–521. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Strayer, Joseph Reese (1992). The Albigensian Crusades. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-06476-2.

- Tolan, John Victor (2002). Saracens: Islam in the Medieval European Imagination. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-12333-4.

- Tolan, John; Veinstein, Gilles; Henry, Laurens (2013). Europe and the Islamic World: A History. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-14705-5.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (2011). A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century. Random House Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-79369-0.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2006). God's War: A New History of the Crusades. Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02387-1.

- Tyerman, Christopher (2007). The Crusades. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-4027-6891-0. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

- Vasilev, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich (1952). History of the Byzantine Empire: 324–1453. University of Wisconsin Press.

- Villegas-Aristizabal, L (2009). "Anglo-Norman involvement in the conquest of Tortosa and Settlement of Tortosa, 1148–1180". Crusades (8): 63–129.

- Wickham, Chris (2009). The Inheritance of Rome: Illuminating the Dark Ages 400–1000. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-311742-1.

- Zacour, Norman P. (1969). "The Children's Crusade". In Wolff, R. L.; Hazard, H. W. The Later Crusades, 1189–1311. pp. 325–342. Retrieved 2016-10-04.

Further information

Introductions

- Andrea, Alfred J. (2003). Encyclopedia of the Crusades. ISBN 0-313-31659-7. OCLC 52030565.

- Asbridge, Thomas (2005). The First Crusade: A New History: The Roots of Conflict between Christianity and Islam. ISBN 0-19-518905-1.

- Cobb, Paul M. The Race for Paradise: An Islamic History of the Crusades (Oxford University Press, 2014)

- France, John (1999). Western Warfare in the Age of the Crusades, 1000–1300. ISBN 0-8014-8607-6. OCLC 40179990.

- Hillenbrand, Carole. The Crusades, Islamic Perspectives. (2000)

- Holt, P.M. The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. (2nd ed. 2014)

- Jotischky, Andrew. The Crusades: a beginner's guide (Oneworld Publications, 2015)

- Madden, Thomas F. The Concise History of the Crusades (Rowman & Littlefield, 2014)

- Murray, Alan V., ed. The Crusades to the Holy Land: The Essential Reference Guide (ABC-CLIO, 2015)

- Phillips, Jonathan. Holy Warriors: A Modern History of the Crusades (2010)

- Phillips, Jonathan. The Crusades, 1095–1204 (2nd ed. Routledge, 2014)

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan, ed. The Atlas of the Crusades (1991)

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The Crusades, Christianity, and Islam (2011)

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan. The crusades: A history (Bloomsbury Publishing, 2014)

Specialised studies

- Boas, Adrian J. Jerusalem in the Time of the Crusades: Society, Landscape, and Art in the Holy City under Frankish Rule (2001)

- Bull, Marcus, and Norman Housley, eds. The Experience of Crusading Volume 1, Western Approaches. (2003)

- Dickson, Gary (2008). The Children's Crusade: Medieval History, Modern Mythistory. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Edbury, Peter, and Jonathan Phillips, eds. The Experience of Crusading Volume 2, Defining the Crusader Kingdom. (2003)

- Florean, Dana. "East Meets West: Cultural Confrontation and Exchange after the First Crusade." Language & Intercultural Communication, 2007, Vol. 7 Issue 2, pp. 144–151

- Folda, Jaroslav. Crusader Art in the Holy Land, From the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre (2005)

- France, John. Victory in the East: A Military History of the First Crusade (1996)

- Harris, Jonathan, Byzantium and the Crusades, Bloomsbury, 2nd ed. (2014) ISBN 978-1-78093-767-0

- Hillenbrand, Car. The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives (1999)

- Housley, Norman. The Later Crusades, 1274–1580: From Lyons to Alcazar (1992)

- James, Douglas. "Christians and the First Crusade." History Review (Dec 2005), Issue 53

- Kagay, Donald J., and L. J. Andrew Villalon, eds. Crusaders, Condottieri, and Cannon: Medieval Warfare in Societies around the Mediterranean. (2003)

- Maalouf, Amin. Crusades Through Arab Eyes (1989)

- Madden, Thomas F. et al., eds. Crusades Medieval Worlds in Conflict (2010)

- Nicolle, David (2007). Crusader Warfare Volume II: Muslims, Mongols and the Struggle against the Crusades.

- Nicolle, David (2003). The First Crusade 1066–99: Conquest of the Holy Land. Campaign. Osprey. ISBN 1-84176-515-5.

- Peters, Edward. Christian Society and the Crusades, 1198–1229 (1971)

- Powell, James M. Anatomy of a Crusade, 1213–1221, (1986)

- Queller, Donald E., and Thomas F. Madden. The Fourth Crusade: The Conquest of Constantinople (2nd ed. 1999)

- Riley-Smith, Jonathan.The First Crusade and the Idea of Crusading. (1986)

- Runciman, Steven. A History of the Crusades: Volume 2, The Kingdom of Jerusalem and the Frankish East (1952) vol 2 online free; A History of the Crusades: Volume 3, The Kingdom of Acre and the Later Crusades (1954); the classic 20th century history

- Setton, Kenneth ed., A History of the Crusades. (1969–1989), the standard scholarly history in six volumes, published by the University of Wisconsin Press

- Includes: The first hundred years (2nd ed. 1969); The later Crusades, 1189–1311 (1969); The fourteenth and fifteenth centuries (1975); The art and architecture of the crusader states (1977); The impact of the Crusades on the Near East (1985); The impact of the Crusades on Europe (1989)

- Smail, R. C. "Crusaders' Castles of the Twelfth Century" Cambridge Historical Journal Vol. 10, No. 2. (1951), pp. 133–149.

- Stark, Rodney. God's Battalions: The Case for the Crusades (2010)

- Tyerman, Christopher. England and the Crusades, 1095–1588. (1988)

Historiography

- Constable, Giles. "The Historiography of the Crusades" in Angeliki E. Laiou, ed. The Crusades from the Perspective of Byzantium and the Muslim World (2001) Extract online.

- Illston, James Michael. 'An Entirely Masculine Activity'? Women and War in the High and Late Middle Ages Reconsidered (MA thesis, University of Canterbury, 2009) full text online

- Madden, Thomas F., ed. The Crusades: The Essential Readings (2002)

- Powell, James M. "The Crusades in Recent Research," The Catholic Historical Review (2009) 95#2 pp. 313–19 in Project MUSE

- Rubenstein, Jay. "In Search of a New Crusade: A Review Essay," Historically Speaking (2011) 12#2 pp. 25–27 in Project MUSE

- von Güttner-Sporzyński, Darius. "Recent Issues in Polish Historiography of the Crusades" in Judi Upton-Ward, The Military Orders: Volume 4, On Land and by Sea (2008) available on Researchgate, available on Academia.edu

Primary sources

- Barber, Malcolm, Bate, Keith (2010). Letters from the East: Crusaders, Pilgrims and Settlers in the 12th–13th Centuries (Crusade Texts in Translation Volume 18, Ashgate Publishing Ltd)

- Bird, Jessalynn, et al. eds. Crusade and Christendom: Annotated Documents in Translation from Innocent III to the Fall of Acre, 1187–1291 (2013) excerpts

- Housley, Norman, ed. Documents on the Later Crusades, 1274–1580 (1996)

- Shaw, M. R. B. ed.Chronicles of the Crusades (1963)

- Villehardouin, Geoffrey, and Jean de Joinville. Chronicles of the Crusades ed. by Sir Frank Marzials (2007)

| Look up Crusade in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crusades. |

"Crusades". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.

"Crusades". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). 1911.- a virtual college course through Boise State University ed. by E. L. Knox

- Crusades: A Guide to Online Resources, Paul Crawford, 1999

- The Society for the Study of the Crusades and the Latin East—an international organization of professional Crusade scholars

- De Re Militari: The Society for Medieval Military History—contains articles and primary sources related to the Crusades

- Real Crusades History – a website about the Crusades