Portuguese settlement in Chittagong

| Portuguese settlement in Chittagong | ||||||||||

| Porto Grande de Bengala (pt) পোর্তো গ্রান্দে দ্য বেঙ্গল (bn) | ||||||||||

| Trading post | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Capital | Firingi Bunder, Chittagong | |||||||||

| Languages | Portuguese, Bengali | |||||||||

| Political structure | Trading post | |||||||||

| Historical era | Imperialism | |||||||||

| • | Permission from the Bengal Sultanate | 1528 | ||||||||

| • | Mughal annexation of Chittagong | 1666 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

Chittagong (Xatigan in Portuguese),[1] the second largest city and main port of Bangladesh, was home to a thriving trading post of the Portuguese Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries.[2] The Portuguese first arrived in Chittagong around 1528 [3] and left in 1666[4] after the Mughal conquest.[5] It was the first European colonial enclave in the historic region of Bengal.[6]

Etymology

Chittagong was the largest seaport in the Sultanate of Bengal, which was termed as the "Shahi Bangalah" (Imperial Bengal) in Persian and Bengali. The Portuguese referred to the port city as Porto Grande de Bengala, which meant "the Grand Harbor of Bengal". The term was often simplified as Porto Grande.[7]

History

.jpg)

On 9 May 1512, a fleet of four ships commanded by João da Silveira from the Estado da India arrived in Chittagong from Goa.[8] They were followed by several embassies from the Kingdom of Portugal to the Sultanate of Bengal, then reputed as the wealthiest region in the Indian subcontinent. He set up the first Portuguese factory in Bengal at Chittagong in 1517.[9] Traders from Portuguese Malacca, Bombay and Ceylon also frequented the region.[8]

Some sources indicate that Joao Coelho had arrived in Chittagong before João da Silveira. Many Malaccan Portuguese had come to the Bengal before Silveira in Moorish ships as traders.[10] Moreover, some of the Portuguese settled in Pipli (present day Orissa) in 1514 and had visited Western Bengal.[11]

In 1528, the Sultan of Bengal permitted the Portuguese to establish factories and customs houses in the Port of Chittagong.[8] A fort and naval base was established in Firingi Bandar. The settlement grew into the most prominent Eurasian port on the Bay of Bengal during the Age of Discovery.[12] The cartaz system was introduced and required all ships in the area to purchase naval trading licenses from the Portuguese.[13][14] In 1590, the Portuguese conquered the nearby islands of Sandwip under the leadership of António de Sousa Godinho.[15] In 1602, the Sandwip island of Chittagong was conquered by the Portuguese from Kedar Rai of Sripur.[16]

Portuguese pirates, named Gonçalves and Carvalho, ruled the island of Sandwip for several years. Each year about 300 salt loaded ships sailed for Liverpool from Sandwip. Sandwip was very famous for its ship-building and salt industries at that time. In 1616, after the arrival of Delwar Khan, a high-ranking Mughal naval officer, the Portuguese pirates were driven away from Sandwip and Delwar Khan ruled the island independently for about 50 years.[17]

The harbor of Chittagong became the most important port to the Portuguese because of its location, navigational facilities and safe anchorage. The port is very close to the mouth of the Meghna which was the principal route to the Royal capital of Gouda.[18]

Evidently the Portuguese found Chittagong a congenial place to live. By the end of the sixteenth century. The Chittagong port had emerged as a thriving port, which attracted both unofficial Portuguese trade and settlement. According to a 1567 note of Caesar Federeci, every year thirty or thirty five ships, great and small, anchored in Chittagong port.[19] In 1598 there lived about 2,500 Portuguese and Eurasians in Chittagong and Arakan.[20][12]

The increased commercial presence included bureaucrats, merchants, missionaries, soldiers, adventurers, sailors and pirates. The enclave had a highly laissez-faire administration led by traders. Slave trade and piracy flourished.[8] Major traded products included fine silk, cotton muslin textiles, bullion, spices, rice, timber, salt and gunpowder.

The Roman Catholic Church was established in Bengal during Portuguese rule in Chittagong. The port city was the seat of the first Vicar Apostolic of Bengal.[21] The Portuguese also encouraged intermarriage with the local population.[22]

In 1615, the Portuguese Navy defeated an Arakanese-Dutch VOC fleet near the port city.[12]

Piracy

The Portuguese presence in Chittagong was ultimately ephemeral. The fall of the Bengal Sultanate and the rise of the Arakanese Kingdom of Mrauk U changed the geopolitical landscape. Chittagong became a major bone of contention between the Mughal Empire, the Kingdom of Mrauk U, the Burmese Empire and the Kingdom of Tripura.[8] The King of Mrauk U massacred 600 members of the Portuguese community in Dianga in 1607.[12][23] Subsequently, the Portuguese allied with Arakan. Portuguese-Arakanese piracy increased against Mughal Bengal in the 17th century.[24] In response, the Portuguese ravaged the Arakan coast and carried off the booty to the king of Barisal.[23]

Slavery

The Portuguese were involved in slave business and sold their slaves in Tamluk and Balasore, and in Deccan ports. They carried off the Hindus and Muslims they could seize, pierced the palms of their hands, passed thin strips of cane through the holes, and threw the men huddled together under the decks of their ships. Every day they flung down some uncooked rice to the captives from above, as people fling grain to the fowl. Slaves were sold at Dianga and Pipli, and transported by ship. The Portuguese built a fort at Pipli in 1599 for prisoners brought by the Arakanese.[25] In 1629 the Portuguese under the command of Diego Da Sa raided Dhaka and took many prisoners including a Syed woman, the wife of a Mughal military officer and carried her off to chains to Dianga. The prisoners were converted to Christianity.[26]

End of settlement

In 1632, the Mughal army expelled the Portuguese from the Satgaon (Hooghly), owing to Portuguese association with the slave trade, kidnapping and refusal to support Shah Jahan.[27][28] In 1666, the Mughal viceroy Shaista Khan retook control of Chittagong after defeating the Arakanese in a naval war.[29] The Mughal conquest of Chittagong brought an end to the Portuguese dominance of more than 130 years in the port city.[30] The conquest of the port of Chittagong was similarly aimed mainly at driving Arakanese slave raiders out of Bengal.[28]

The Mughals attacked the Arakanese from the jungle with a 6500-man army supported by 288 ships of war bound for the seizure of Chittagong harbor. After three days of battle, the Arakanese surrendered. Chittagong promptly became the capital of the new Government.[4]

This battle involved movement across both land and water. In order to combat the pirates' skill over water, the Mughals called for the support of Dutch ships from Batavia. Before the Dutch ships reached the coast of Chittagong, the battle had already ended. In order to carry soldiers, Shaista Khan constructed several large ships and a large number of galleys.[31] After the Mughals took Chittagong, the Portuguese moved to the Ferengi Bazaar in Dhaka. Descendants of the Portuguese still reside in these places.[20]

Other settlements

From Chittagong, the Portuguese proceeded to establish settlements in other Bengali ports and cities, notably Satgaon, Bandel and Dhaka. Satgaon became known as Porto Pequeno (Little Haven). Portogola in Old Dhaka hosted the city's Portuguese community.[12]

Spreading of Christianity

Christianity spread across Bengal by the Portuguese traders along with the Christian missionaries. Although Christianity had already reached Bengal with Thomas the Apostle in 52 CE, the Portuguese set up the first Christian churches in Chittagong.[32] The Portuguese merchants, most of whom were Christian, called Chittagong as Porto Grande de Bengala. In 1498, Christian explorer Vasco de Gama traveled Bengal.[33]

Legacy

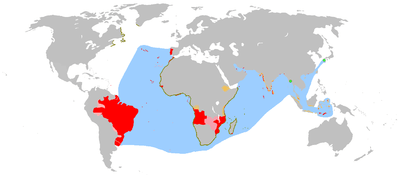

The descendants of the Portuguese traders in Chittagong are known as Firingis. They live in the areas of Patherghatta and Firingi Bazaar in Old Chittagong.[34] There are numerous Portuguese loanwords in the Bengali language, including many common household terms, particularly in Chittagonian Bengali.[35] The Portuguese brought many exotic fruits, flowers and plants, especially from their South American Brazilian colony. They introduced chillies, delonix regia, guavas, pineapples, papayas and Alfonso mangoes to Bengal.[8]

A Portuguese missionary in British Calcutta published the first book on Bengali grammar.[35] The oldest churches in Bangladesh and West Bengal trace their origins to Portuguese missionary missions which arrived in Chittagong in the 16th century. Most Bangladeshi Christians have Portuguese surnames.[35]

After the independence of Bangladesh, Portugal recognized it on 20 December 1974 following the Carnation Revolution, when it established relations with many decolonized nations.[36] The Portuguese have had a great influence on trade, culture, character and language of the people of Chittagong.[32]

Very few physical vestiges of the Portuguese presence are found at present in Chittagong and Bengal, generally. Darul Adalat, the first court building of Chittagong is located in the Government Hazi Mohammad Mohshin College campus, is a structure built by the Portuguese. The structure is locally known as Portuguese Fort. Initiative has been taken by the Department of Archaeology of Bangladesh to preserve the vestige.[37]

There are few churches and ruins. Some geographical place names remain, like Dom Manik Islands, Point Palmyras on the Orissa coast, Firingi Bazaar in Dhaka and Chittagong.[38]

See also

- Dutch settlement in Rajshahi

- Armenian community of Dhaka

- History of Bombay under Portuguese rule (1534-1661)

References

- ↑ Sircar 1971, p. 138.

- ↑ Rahman 2010, p. 24.

- ↑ Gupta 2014, p. 22.

- 1 2 Trudy 1996, p. 188.

- ↑ Eaton 1996, p. 235.

- ↑ Dasgupta 2005, p. 258.

- ↑ Mendiratta & Rossa 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ray 2012.

- ↑ Dasgupta 2005, p. 259.

- ↑ Wallcousins 1993, p. 169.

- ↑ UK Essays.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ramerini.

- ↑ Gin 2004, p. 870.

- ↑ Pearson 2006, p. 78.

- ↑ Gupta 2014, p. 23.

- ↑ Mandal 2003, p. 44.

- ↑ The Guardian Editorial 2013.

- ↑ Lahore University 2007.

- ↑ Roy 2007, p. 12.

- 1 2 Hasan 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ Catholic Diocese.

- ↑ Agnihotri 2010, p. B-276.

- 1 2 Rizvi, S.N.H. (1965). "East Pakistan District Gazetteers" (PDF). GOVERNMENT OF EAST PAKISTAN SERVICES AND GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (1): 74–76. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Konstam 2008, p. 250.

- ↑ Dasgupta 2005, p. 267.

- ↑ Rizvi, S.N.H. (1965). "East Pakistan District Gazetteers" (PDF). GOVERNMENT OF EAST PAKISTAN SERVICES AND GENERAL ADMINISTRATION DEPARTMENT (1): 84. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Roy 2007, p. 13.

- 1 2 Chatterjee and Eaton 2006, p. 13.

- ↑ Tavernier 2012, p. 129.

- ↑ Johnston 2008, p. 442.

- ↑ Dasgupta 2005, p. 264.

- 1 2 Meggitt 2012, p. 223.

- ↑ R. Islam.

- ↑ Bangladesh Channel.

- 1 2 3 A.K. Rahim.

- ↑ Portuguese in Bangladesh.

- ↑ Uddin, Minhaj (23 May 2014). "Centuries-old Darul Adalat's existence hangs in balance". The Daily Star. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Hosking 2009, p. 290.

Bibliography

- Agnihotri, V.K. (2010). Indian History (Twenty Sixth ed.). Allied Publishers. ISBN 8184245688. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Dasgupta, Biplab (1 January 2005). European trade and colonial conquest. (1. publ. ed.). London: Anthem Press. ISBN 1843310295.

- Eaton, Richard M. (1996). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal frontier, 1204 - 1760 (First paperback ed.). Berkeley [u.a.]: Univ California Pr. p. 235. ISBN 0520205073. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Gin, Ooi Keat (Editor) (1 January 2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, Calif. [u.a.]: ABC Clio. ISBN 1576077705. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Gupta, Taniya; Edited by Antonia Navarro-Tejero (8 January 2014). "Chapter two". India in Canada Canada in India. (1. publ. ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1443855715.

- Gupta, Taniya; Edited by Antonia Navarro-Tejero (8 January 2014). "Chapter two". India in Canada Canada in India. (1. publ. ed.). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 1443855715.

- Johnston, Douglas M. (2008). "Chapter 7". The historical foundations of world order : the tower and the arena. Leiden: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 9004161678. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Konstam, Angus (2008). "The Pirate Round". Piracy : the complete history. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 1846032407. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Mandal, Asim Kumar (2003). The Sundarbans of India : a development analysis. New Delhi: Indus Publ. Co. ISBN 8173871434. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- Mendiratta, Sidh Losa; Rossa, Walter (2015). "Porto Grande de Bengala:Historical Background and Urbanism". Heritage of Portuguese Influence. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- Pearson, M.N. (2006). The Portuguese in India (Digitally print. 1. pbk. version. ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521028507. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Rahman, Syedur (2010). "Arakan". Historical dictionary of Bangladesh (4th ed.). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0810874539. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Ramerini, Marco. "The Portuguese on the Bay of Bengal". Colonial Voyage. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Ray, Aniruddha (2012). "Portuguese, The". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- Sircar, D. C. (1971). Studies in the geography of ancient and medieval India (2nd ed. rev. and enlarged. ed.). Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 8120806905.

- Tavernier, Jean Baptiste; [translated by V.Ball] (2012). Travels in India. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 1108046029. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- Trudy, Ring; M. Salkin,Robert; La Boda,Sharon; Edited by Trudy Ring (1996). International dictionary of historic places. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers. ISBN 1884964044. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- "The Early Years of the Church in Chittagong Diocese". Catholic Diocese. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Rahim, AK (25 January 2014). "Você fala Bangla?". Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- Islam, Reema (18 December 2014). "The Christian community". The Dhaka Tribune. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- "Bangladesh Portugal Bilateral Relations". Honorary Consulate of Portugal. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Wallcousins, Harry Johnston ; with eight coloured illustrations (1993). Pioneers in India (Nouvelle édition. ed.). New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 8120608437. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Bangladesh Channel Services. "Explore the wonders of Chittagong in Bangladesh". Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Meggitt, Mikey Leung, Belinda (2012). Bangladesh : the Bradt travel guide (2nd ed.). Chalfont St. Peter: Bradt Travel Guides. ISBN 1841624098. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Hosking, edited by Richard (2010). Food and language : proceedings of the Oxford Symposium on Food and Cookery 2009. Totnes: Prospect Books. ISBN 978-1903018798. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Editorial. "Sandwipees should respond to the call of Master Shahjahan for development of Sandwip". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Lahore University, Department of Geography. "Pakistan geographical review". Journal of University of the Punjab. 62 (2). ISSN 0030-9788. OCLC 655502543. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Ray, Jayanta Kumar (2007). Aspects of India's International relations, 1700 to 2000 : South Asia and the World. New Delhi: Pearson Longman, an imprint of Pearson Education. ISBN 8131708349.

- Indrani, Chatterjee; Richard, M. Eaton, eds. (2006). Slavery and South Asian History. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253116716. Retrieved 12 July 2015.

- Samiul Hasan, ed. (2012). The Muslim world in the 21st century : space, power, and human development. New York: Springer. ISBN 9400726325. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

_uncrowned_shield.svg.png)