German mediatization

German mediatization (English /miːdiətaɪˈzeɪʃən/; German: deutsche Mediatisierung) was the major territorial restructuring that took place between 1802 and 1814 in Germany and the surrounding region (until 1806 the Holy Roman Empire) by means of the mass mediatization and secularization[1] of a large number of Imperial Estates: ecclesiastical principalities, free imperial cities, secular principalities and other minor self-ruling entities that lost their independent status and were absorbed into the remaining states.

In the strict sense of the word, mediatization consists in the subsumption of an immediate (German: unmittelbar) state into another state, thus becoming mediate (mittelbar), while generally leaving the dispossessed ruler with his private estates and a number of privileges and feudal rights, such as low justice. For convenience, historians use the term mediatization for the entire restructuring process that took place at the time, whether the mediatized states survived in some form or lost all individuality. The secularization of ecclesiastical states took place concurrently with the mediatization of free imperial cities and other secular states.

The mass mediatization and secularization of German states that took place at the time was not initiated by Germans. It came under relentless military and diplomatic pressure from revolutionary France and Napoleon. It constituted the most extensive redistribution of property and territories in German history prior to 1945.[2]

The two highpoints of the process were the secularization/annexation of ecclesiastical territories and free imperial cities in 1802–03, and the mediatization of secular principalities and counties in 1806.

Background

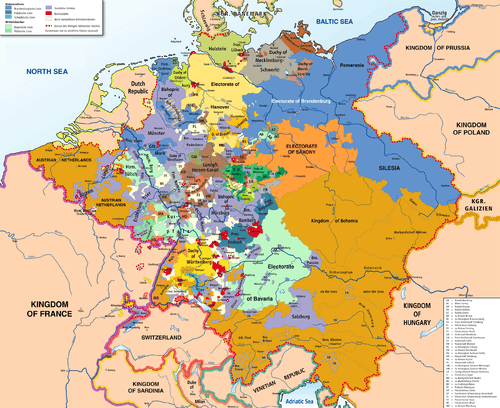

Germany before the 19th century did not coalesce into a relatively centralized nation like most of its neighbors did. Instead, the Holy Roman Empire ended up being a "polyglot congeries of literally hundreds of nearly sovereign states and territories ranging in size from considerable to minuscule".[3] From a high of nearly 400 — 136 ecclesiastical and 173 secular lords plus 85 free imperial cities — on the eve of the Reformation, the number had gone down to less than 300 by the late 18th century, still a considerable number.[4] The traditional explanation for this fragmentation has focused on the gradual usurpation by the princes of the powers of the Emperor during the Staufen period, to the point that by the Peace of Westphalia, the Emperor had become a mere primus inter pares. In recent decades, many historians have maintained that the fragmentation of Germany — which started out big while its neighbors started small — can be traced back to the geographical extent of the Empire — the German part of the Empire being about twice the size of the realm controlled by the king of France in the second half of the 11th century — and the vigor of local aristocratic and ecclesiastical rule from early on in the medieval era. Already in the 12th century, the secular and spiritual princes did not regard themselves as the Emperor’s subordinates, still less his subjects, but as rulers in their own rights and they jealously defended their established sphere of predominance.[5] At the time of Emperor Frederick II's death, it had already been decided that the regnum teutonicum was "an aristocracy with a monarchical head".[6]

Among those states and territories, the ecclesiastical principalities were unique to Germany. Historically, the Ottonian and early Salian Emperors, who appointed the bishops and abbots, used them as agents of the crown as they considered them more dependable than the dukes they appointed and who often attempted to establish independent hereditary principalities. The emperors expanded the power of the Church, and especially of the bishops, with land grants and numerous privileges of immunity and protection as well as extensive judicial rights, which eventually coalesced into a distinctive temporal principality: the hochstift. The German bishop became a "prince of the Empire" and direct vassal of the Emperor for his hoschstift,[7] while continuing to exercise only pastoral authority over his larger diocese. The personal appointment of bishops by the Emperors had sparked the investiture controversy, and in its aftermath the emperor‘s control over the bishops’ selection and rule was considerably diminished. The bishops, now elected by independent-minded cathedral chapters rather than chosen by the emperor or the pope, were confirmed as territorial lords equal to the secular princes.

Secularization

Early secularizations

Having to face with the territorial expansionism of the increasingly powerful secular princes, the position of the prince-bishops became more precarious with time. In the course of the Reformation, several of the bishoprics in the north and northeast were secularized, mostly to the benefit of Protestant princes. In the later sixteenth century the Counter-Reformation attempted to reverse some of these secularizations, and the question of the fates of secularized territories became an important one in the Thirty Years War (1618–1648). In the end, the Peace of Westphalia confirmed the secularization of a score of prince-bishoprics, including the archbishoprics of Bremen and Magdeburg and six bishoprics with full political powers,[8] which were assigned to Sweden, Brandenburg and Mecklenburg. On the other hand, Hildesheim and Paderborn – under Protestant administration for decades and given up for lost – were restored as prince-bishoprics.[9] In addition, the Peace conclusively reaffirmed the imperial immediacy, and therefore the de facto independence, of the prince-bishops and imperial abbots, free imperial cities, imperial counts, as well as the imperial knights. According to one authority, the sixty-five ecclesiastical rulers then controlled one-seventh of the total land area and approximately 12% of the Empire’s population, perhaps three and a half million subjects.[10]

Due to the traumatic experience of the Thirty Years’ War and in order to avoid a repetition of this catastrophe, the German rulers great or small were now inclined to value law and legal structures more highly than ever before in the history of the Empire. This explains in good part why medium and small states, both ecclesiastical and secular, were able to survive and even prosper in the vicinity of powerful states with standing armies such as Brandenburg/Prussia, Bavaria and Austria.[11]

Eighteenth century secularization plans

While no actual secularization took place during the century and a half that followed the Peace of Westphalia, there was a long history of rumors and half-baked plans on possible secularizations. The continued existence of independent prince-bishoprics, an anomalous phenomenon unique to the Holy Roman Empire, was increasingly considered an anachronism especially, but not exclusively, by the Protestant princes, who also coveted these defenseless territories. Thus, secret proposals by Prussia to end the War of the Austrian Succession called for increasing the insufficient territorial base of the Wittelsbach Emperor Charles VII through his annexation of some prince-bishoprics[12] In 1743, Frederick II's minister Heinrich von Podewils wrote a memorandum that suggested giving to the Wittelsbach Emperor the bishoprics of Passau, Augsburg and Regensburg, as well as the imperial cities of Augsburg, Regensburg and Ulm. Frederick II added the archbishopric of Salzburg to the list and Charles VII went as far as adding the bishoprics of Eichstätt and Freising. The plan caused a sensation, and outrage among the prince-bishops, the free imperial cities and the other minor imperial estates, and the bishops discussed raising an army of 40,000 to defend themselves against the Emperor who contemplated grabbing ecclesiastical land that his coronation oath committed him to protect.[13] Although the sudden death of Charles VII put an end to these scheming, the idea of secularization did not fade away. It was actively discussed during the Seven Years’ War, and again during Joseph II’s maneuverings over the Bavarian inheritance[14] and during his later exchange plan to swap Bavaria for the Austrian Netherlands, which included a secret provision for the secularization of the Archbishopric of Salzburg and the Provostry of Berchtesgaden. Yet, none of these projects ever came close to be implemented because, in the end, key actors appreciated that the secularization of one single prince-bishopric would open a Pandora's box and have severe repercussions on the institutional stability of the Empire.

Impact of the French Revolution

In the late 18th century, the continued existence of the Holy Roman Empire, despite its archaic constitution, was not seriously threatened from the inside. It took an external factor — the French Revolution — to shake the Empire to its foundation and bring its demise.

After Revolutionary France had declared war on Prussia and Austria in April 1792, its armies had invaded and eventually consolidated their hold over the Austrian Netherlands and the rest of left bank of the Rhine by the end of 1794. By then, the French leaders had already resolved more or less openly to annex those lands to the Republic as soon as circumstances permitted. Persuading the German states and princes that were fated to lose their possessions west of the Rhine to come to terms with what amounted to massive French spoliation of German land by compensating themselves with land on the right bank became a constant objective of the French revolutionaries and later Napoleon Bonaparte. Moreover, given that the German Catholic clergy at all levels were the most implacable enemies of the "godless" Republic, and had actually provided the first cause of war between France and the Holy Roman Empire through provocative action such as allowing émigré French nobles to carry on counterrevolutionary activities from their land, the French leaders estimated that the ecclesiastical rulers and other clerics — who collectively were the ones who were losing the most on the left bank — should be excluded from any future compensation. On the other hand, the secular rulers entitled to compensation should be compensated with secularized ecclesiastical land and property located on the right bank.[15][16]

Already, the Franco-Prussian Treaty of Basel of April 1795 spoke of "a compensation" in case a future general peace with the Holy Roman Empire surrendered to France the German territories west of the Rhine, including the Prussian provinces. A secret Franco-Prussian convention signed in August 1796 spelled out that such a compensation would be the Prince-Bishopric of Münster and Vest Recklinghausen.[17] In addition, article 3 provided that the Prince of Orange-Nassau, dynastically related to the king of Prussia who actively defended his interests, would be compensated with the Prince-Bishoprics of Würzburg and Bamberg if his loss of the Dutch hereditary stadtholdership, which followed the creation of the French-backed Batavian Republic, was to become permanent.[18] Likewise, the peace treaties France signed with Württemberg and Baden the same month contained secret articles whereby France committed to intercede to obtain the cession of specific ecclesiastical territories as their compensation in case their losses became permanent.[19]

Signed in the wake of major French victories over the Austrian armies, the Treaty of Campo Formio of October 1797, dictated by General Bonaparte, provided that Austria would be compensated for the loss of the Austrian Netherlands and Austrian Lombardy with Venice and Dalmatia. A secret article, not implemented at the time, added the Archbishopric of Salzburg and a portion of Bavaria as additional compensation. The treaty also provided for the holding of a congress at Rastatt where delegates of the Imperial Diet would negotiate a general peace with France. It was widely and correctly anticipated that France would demand the formal cession of the entire west bank, that the dispossessed secular princes be compensated with ecclesiastical territories east of the Rhine, and that a specific compensation plan be discussed and adopted.[20][21] Indeed, on 9 March 1798, the delegates at the congress at Rastatt formally accepted the sacrifice of the entire left bank and, on 4 April 1798, approved the secularization of all the ecclesiastical states save the three Electorates of Mainz, Cologne and Trier, whose continued existence was an absolute red line for Emperor Francis II.[22] The congress, which lingered on well into 1799, failed in its other goals due to disagreement among the delegates on the repartition of the secularized territories and insufficient French control over the process caused by the mounting power struggle in Paris.

In March 1799, Austria, allied with Russia, resumed the war against France. A series of military defeats and the withdrawal of Russia from the war forced Austria to seek an armistice and, on 9 February 1801 to sign the Treaty of Lunéville which mostly reconfirmed the Treaty of Campo Formio and the guidelines set at Rastatt.[23] Article 7 of the treaty provided that "in conformity with the principles formally established at the congress of Rastatt, the empire shall be bound to give to the hereditary Princes who shall be dispossessed on the left bank of the Rhine, an indemnity, which shall be taken from the whole of the empire, according to arrangements which on these bases shall be ultimately determined upon."[24] This time, Francis II signed the treaty not only on Austria’s behalf but also on behalf of the Empire, which officially conceded the loss of the Austrian Netherlands and the left bank of the Rhine.[25]

Raging debate on compensation and secularization

The sudden realization in wake of Campo Formio that the Empire was on the threshold of radical changes triggered a heated debate on the issues of compensation and secularization conducted in pamphlets, in the press, in the political correspondence within and between the territories and at the Imperial Diet.[26] Among other arguments, the defenders of the ecclesiastical states insisted that it was fundamentally illegal and unconstitutional to dissolve any imperial estates, and that the notion of compensating rulers for lost territory was contrary to all past treaties, where "each had to bear his own fate". They contended that even if circumstances now made it necessary, the amount of compensation should be limited to the amount of territory, or income, lost, and that all the Estates of the Empire, and not just the ecclesiastical states, should bear the burden. They warned that a complete secularization would be such a blow to the Empire that it would lead to its demise.[27][28] Generally, the proponents of secularization were less vocal and passionate, in good part because they realized that the course of events was in their favor. Even when they were in agreement with some of the anti-secularization arguments, they contended that Notreich (the law of necessity) made secularization unavoidable: the victorious French unequivocally demanded it and since peace was essential to the preservation of the state, sacrificing part of the state to preserve the whole was not only permissible but necessary.[29] For its part, Austria was to be consistently hostile to secularization, in particular, to wholesale secularization, since it realized it had more to lose than to gain from it as it would result in the disappearance of the ecclesiastical princes and prelates from the Imperial Diet and the loss of their traditional support for the Emperor.[30] Likewise, the Electors of Hanover and Saxony opposed the principles of compensation and secularization, not out of sympathy for the Catholic Church, but because they feared it would lead to the aggrandizement of Prussia, Austria and Bavaria.[31]

Final Recess of February 1803

The Final Recess of the Imperial Deputation (German: Reichsdeputationshauptschluss) of 25 February 1803 is commonly referred to as the Imperial law that brought about the territorial restructuring of the Empire by reallocating the ecclesiastical states and the imperial cities to other imperial estates. In reality, neither the Final Recess nor the Imperial Deputation which drafted it played a significant role in the process since many key decisions had already been taken behind closed doors in Paris before the Deputation even started its work. The Final Recess was nevertheless indispensable since it bestowed a constitutional seal of approval on the major territorial and political restructuring that would otherwise have lacked legitimacy.

Background

Hard-pressed by Bonaparte, now firmly at the helm in France as First Consul, the Empire was obliged soon after Lunéville to take on the task of drawing up a definitive compensation plan (Entschädigungsplan). The Imperial Diet resolved to entrust that task to the Emperor, as plenipotentiary of the Empire, while it intended to reserve the final decision to itself. Not wanting to bear the full onus of the changes that were bound to occur under French dictate, Francis II declined. After months of deliberations, a compromise was reached in November 1801 to delegate the compensation task to an Imperial Deputation (Reichsdeputation), with France to act as 'mediator'. The Deputation consisted of the plenipotentiaries of the Electors of Mainz, Saxony, Brandenburg/Prussia, Bohemia and Bavaria, and of the Duke of Württemberg, the Landgrave of Hesse-Cassel and the Grand Master of the Teutonic Order.[32][33]

Soon after Lunéville, the key German rulers entitled to compensation moved quickly to secure their compensation directly with France, and Paris was soon flooded with envoys bearing shopping lists of coveted territories. The French government encouraged the movement.[34] Bonaparte left the details to his foreign minister Talleyrand, who famously lined his pockets with bribes.[35][36] Meanwhile, Bonaparte, who had been courting the new Tsar Alexander I, replied favourably to the latter’s wish to become involved in the process as co-mediator. On 19 October 1801 the two countries signed an agreement to act jointly as the “mediating Powers”.[37] Essentially, Alexander, whose wife and mother belonged to the princely houses of Baden and Württemberg, wanted to favor his various German relatives and this concurred with France’s long-standing aim to strengthen the southern states of Baden, Württemberg, Hesse-Darmstadt and Bavaria, strategically located between France and Austria, the arch-foe.[38][39] Hectic discussions and dealings went on, not only with the mediating Powers and between the various princes, but within the various governments as well. Inside the Prussian cabinet, one group pushed for expansion westward into Westphalia while another favored expansion southward into Franconia, with the pro-Westphalian group finally prevailing.[40] Between July 1801 and May 1802, preliminary compensation agreements were signed with Bavaria, Württemberg, and Prussia and others were concluded less formally with Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt, Hesse-Cassel and other mid-level states.[41]

Frantic discussions and dealings went on simultaneously in Regensburg, where the Imperial Diet and its Deputation were in session. In particular, many mid and lower ranking rulers who lacked influence in Paris — the dukes of Arenberg, Croy and Looz, the prince of Salm-Kyrburg, the counts of Sickingen and Wartenberg, among others — tried their chances with the French diplomats posted at Regensburg, who could recommend additions or amendments to the general compensation plan, generally in exchange for bribes.[42] Nevertheless, all claims were examined and there was an effort to detect fictitious or exaggerated claims. The Imperial Deputation very seldom examined the claims and grievances, which were almost automatically transferred to the local French officials for decision or referral to Talleyrand in Paris.[43][44]

General compensation plan

A "general compensation plan" combining the various formal and informal accords concluded in Paris was drafted by Talleyrand in June 1802, approved by Russia with minor changes,[45] and submitted almost as an ultimatum to the Imperial Deputation when it finally convened at Regensburg for its first meeting on 24 August 1802. It was stated in the preamble that the mediating Powers had been forced to come up with a compensation plan due to the ‘irreconcilable differences between the German Princes” regarding the details of compensation, and the Imperial Deputation’s delay in starting its work. It was said that the plan, “based on calculations of unquestionable impartiality” endeavored to effect compensation for recognized losses while “maintaining the pre-war balance of power between the key German rulers”, two goals that were somewhat contradictory.[46] The original rationale for compensation, which had been to compensate strictly for territory lost, had been replaced by political objectives: to favor powerful or well-connected rulers and to woo potential allies.

As Austria had been excluded from the discussions, its envoy at Paris only learned of the plan when he read it in Le Moniteur. He swiftly negotiated revisions which confirmed both Francis II’s Imperial prerogatives and his rights as ruler of Austria. The Habsburg’s compensation package was also augmented with additional secularized bishoprics.[47] Francis II had been hostile to secularization, but once it became clear that near complete secularization was unavoidable, he fought as hard as any other ruler to obtain his share of the sploils. He was particularly adamant that his younger brother Ferdinand, who had been dispossessed of his secundogeniture Grand duchy of Tuscany by the invading French, be adequately compensated.

The Imperial Deputation, originally entrusted with the compensation process but now reduced to a subordinate role, tended to be seen by the mediating Powers and the key German States as mere constitutional window dressing. This was demonstrated with the Franco-Prussian agreement of 23 May 1802 which, ignoring the Imperial Deputation that has not yet convened, stated that both the King of Prussia and the Prince of Orange-Nassau could take possession of the territories allotted to them immediately after ratification.[48] Two weeks later, the King issued a proclamation listing all the compensation territories awarded to Prussia but he waited until the first week of August 1802 before occupying the bishoprics of Paderborn and Hildesheim and its share of Münster, as well as the other territories that had been allotted to Prussia. The same month, Bavarian troops entered Bamberg and Würzburg a week after Elector Maximilian IV Joseph had written to their respective prince-bishops to inform them of the imminent occupation of their principalities.[49] During the autumn, Bavaria, Baden, Hesse-Darmstadt and Württemberg, and even Austria, proceeded to occupy the prince-bishoprics imperial abbeys and free imperial cities that had been allotted to them. Formal annexation and the establishment of a civil administration usually followed within a few weeks. Such haste was due in good part to the fear that the June plan might not be definitive and therefore it was thought safer to occupy the allotted territories and place everyone before a fait accompli. That strategy was not foolproof however and Bavaria, which had been in occupation of the bishopric of Eichstätt since September, was forced to evacuate it when the Franco-Austrian convention of 26 December 1802 reallocated most of Eichstätt to the Habsburg compensation package.[50] For their parts, the lesser princes and the counts, with little manpower and resources, generally had to wait until the Final Recess was issued before they could take possession of the territories — if any — that were awarded to them as compensation, usually a secularized abbey or one of the smaller imperial cities.

Approval and ratification of the Final Recess

On 8 October 1802, the mediating Powers transmitted to the Deputation their second general compensation plan whose many modifications reflected the considerable number of claims, memoirs, petitions and observations they had received from all quarters. A third plan was transmitted in November and a final one in mid-February 1803. It served as the basis for the Final Recess that the Deputation issued at its 46th meeting on 25 February 1803.[51] The Imperial Diet approved it on 24 March and the Emperor ratified it on 27 April.[52] The Emperor however made a formal reservation with respect to the reallocation of seats and votes within the Imperial Diet. While he accepted the new ten-member College of Electors, which would for the first time have a Protestant majority,[53] he objected to the strong Protestant majority within the new College of Princes (77 Protestant vs 53 Catholic votes, plus 4 alternating votes), where traditionally the Emperor’s influence had been the most strongly felt, and he proposed religious parity instead.[54] Discussions regarding this matter were still ongoing when the Empire was dissolved in 1806.

Consequences

End of the ecclesiastical principalities

.jpg)

Under the terms of the Final Recess, all the ecclesiastical principalities – archbishoprics, bishoprics and abbeys – were dissolved except for the Archbishopric-Electorate of Mainz, the Teutonic Order and the Order of Malta. Archbishop Karl Theodor von Dalberg of Mainz had salvaged his Electorate by convincing Bonaparte that his position as Imperial Archchancellor was essential to the functioning of the Empire. As much of his Electorate, including the cathedral city of Mainz, has been annexed by France, the archbishopric was translated to Regensburg and augmented with some remnants of the Electorate east of the Rhine, and Wetzlar. Dalberg, who was confirmed as Elector and Imperial Archchancellor and gained the new title of Primate of Germany, was to prove a constant and useful ally of Napoleon during the coming years.[55][56] In addition, under the dogged insistence of the Emperor, the Teutonic Order, whose Grand Master was generally an Austrian archduke, as well as the Knights of St John (Knights of Malta), were also spared and their scattered small domains were augmented with several nearby abbeys. The intent here was to provide livings for some of the 700 noble members of the cathedral chapters whose property and estates had been expropriated when the prince-bishoprics were secularized.[57][58] Some prince-bishoprics were transferred whole to a new owner while others, such as Münster, Trier, Cologne, Würzburg, Augsburg, Freising, Eichstätt, Passau and Constance, were either split between two or several new owners or had some districts or exclaves allotted to different new owners. The substantial property and estates of the bishoprics’ cathedral chapters were also expropriated.

The Final Recess detailed the financial and other obligations of the new rulers toward the former rulers, dignitaries, administrators and other civilian and military personnel of the abolished ecclesiastical principalities. The former prince-bishops and prince-abbots remained immediate to the emperor for their own person. They retained extensive authority, including judicial jurisdiction in civil and some criminal matters over their servants (art. 49). They retained the title and ranking of prince-bishop or prince-abbot for life and were entitled to a number of honors and privileges (art. 50). However, the prince-bishops palatial residences, such as the Würzburg Residence and Schloss Nordkirchen, passed to new owners and the bishops were granted more modest lodgings as well as the use of a summer residence. The former prince-bishops, prince-abbots and imperial abbots and abbesses were entitled to an annual pension ranging from 20,000 to 60,000 gulden, 6,000 to 12,000 gulden and 3,000 to 6,000 gulden respectively, depending on their past earnings (art. 51). While secularization stripped the prince-bishops of their political power and abolished their principality, they were still bishops and they retained normal pastoral authority over their diocese, parishes and clergy. Some, such as Bishop Christoph Franz von Buseck of Bamberg, adjusted to their diminished circumstances and stayed in their diocese to carry on their pastoral duties,[59] other, such as Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo of Salzburg, abandoned their pastoral duties to auxiliary bishops and went to live in Vienna or on their family estates.

End of the free imperial cities

The 51 free imperial cities[60] had less to offer in the way of territory (7,365 square kilometres (2,844 sq mi)) or population (815,000) than the ecclesiastical states but the secular princes had long resented the independence of the ones enclaved within their territory. With a few exceptions, they suffered from an even worse reputation of decay and mismanagement than the ecclesiastical states.[61][62]

A few imperial cities had been included in some of 18th century stillborn secularization plans, chiefly because they were either contiguous to or enclaved within a prince-bishopric targeted for secularization. While the secret compensation provisions of the treaties of 1796 with Prussia, Baden and Württemberg targeted only ecclesiastical territories, by the time the Congress of Rastatt opened in late 1797, there were widespread rumors about the abolition of at least some cities. Alarmed by such rumors, the imperial cities of the Swabian Circle, where about half of all the imperial cities were located, held a special conference at Ulm in early March 1798 to examine the situation, for which they felt helpless.[63] However, given that it was expected from the start that the handful of the largest and wealthiest cities would maintain their independence, the expected mediatization of the imperial cities did not raise much public interest.[64] The survival of an imperial city often hung by a thread: while Regensburg and Wetzlar, seats of the Imperial Diet and the Imperial Cameral Tribunal respectively, were still on the short list of imperial cities that were to survive in the June 1802 general compensation plan, they were secularized a few months later in order to beef up the newly created Principality of Aschaffenburg that was to constitute the territorial base of Archbishop von Dalberg, the Imperial Archchancellor. In the end, only Hamburg, Bremen, Lubeck, Frankfurt, Augsburg, and Nuremberg survived mediatization in 1803.

Far-reaching political and religious consequences

While the original intent had been to compensate the dispossessed secular rulers only for lost territory, that criterion was to be applied only to the minor princes and the counts who sometimes only received an annuity or a territorial compensation that so modest that it had to be augmented with an annuity paid by better provided princes in order that their total income would not be less than their former income.[65]

In the case of the larger states, they generally received more than the territory they had lost. Baden received over seven times as much territory as it had lost, Prussia nearly five times. Hanover gained the Prince-Bishopric of Osnabrück, even though it had lost nothing. The Duchy of Oldenburg, closely connected to Tsar Alexander I, received a sizeable chunk of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster although it had lost only the income of a toll station. Austria also did relatively well.[66] In addition, the two Habsburg archdukes who had been dispossessed of their Italian realms (the Grand Duchy of Tuscany and the Duchy of Modena) were also compensated even though their realms were not part of the Holy Roman Empire. Likewise, the King of Prussia was able to obtain a generous territorial compensation for the dynastically related Prince of Orange-Nassau whose losses had been in the defunct Dutch Republic.

In all, 112 imperial estates disappeared. Apart from the territory ceded to France, their land and properties were distributed among the seventy-two rulers entitled to compensation.[67]

The outcome of the compensation process confirmed by the Final Recess of February 1803 was the most extensive redistribution of property in German history before 1945. Approximately 73,000 km2 (28,000 sq mi) of ecclesiastical territory, with some 2.36 million inhabitants and 12.72 million guildens per annum of revenue was transferred to new rulers.[68]

The position of the established Roman Catholic Church in Germany, the Reichskirche, was not only diminished, it was nearly destroyed. The Church lost its crucial constitutional role in the Empire; most of the Catholic universities were closed, as well as hundreds of monasteries and religious foundations. It has been said that the Final Recess of 1803 did to German land ownership what the Revolution had done to France.[69]

Mediatization from 1806

On 12 June 1806, Napoleon established the Confederation of the Rhine to extend and help secure the eastern border of France. In reluctant recognition of Napoleon's dismemberment of imperial territory, on 6 August 1806, the Holy Roman Emperor Francis II declared the Empire abolished, and claimed as much power as he could retain as ruler of the Habsburg realms. To gain support from the more powerful German states, the former Holy Roman Emperor accepted, and Napoleon encouraged, the mediatisation by those that remained of their minor neighbouring states. Mediatization transferred the sovereignty of more than 100 small secular states to their larger neighbours, most of whom became founding members of the Confederation in order to participate in the annexations.

| Losses | Gains | |

|---|---|---|

| 2,000 km² 140,000 people |

12,000 km² 600,000 people | |

| 10,000 km² 600,000 people |

14,000 km² 850,000 people | |

| 450 km² 30,000 people |

2,000 km² 240,000 people | |

| 400 km² 30,000 people |

1,500 km² 120,000 people |

Between the first abdication of Napoleon in 1814 and the Battle of Waterloo and the final abdication of Napoleon in 1815, the Congress of Vienna was convened by the Great Powers to redraw the borders of Europe. During this time, it was decided that the mediatised principalities, free cities, and secularised states would not be reinstated. Instead, the former rulers who held a vote within the Imperial Diet were to enjoy an improved aristocratic status, being deemed equal to the still-reigning monarchs for marital purposes, and entitled to claim compensation for their losses. But it was left to each of the annexing states to compensate mediatised dynasties, and the latter had no international right to redress if dissatisfied with the new regime's reimbursement decisions. In 1825 and 1829, those houses which had been designated the "Mediatized Houses" were formalised, at the sole discretion of the ruling states, and not all houses that ruled states that were mediatised were recognised as such.

As a result of the Congress of Vienna, only 39 German states remained.

Appendix

Disbursement of the prince-bishoprics and archbishoprics

| Awarded to | Mediatized state |

|---|---|

| France and client states (previously annexed) |

|

| Duke of Arenberg | |

| Archduke of Austria | |

| Margrave of Baden |

|

| Elector of Bavaria | |

| Duke of Croÿ | |

| Elector of Hanover | |

| Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt |

|

| Duke of Looz-Corswarem |

|

| Princes of Nassau |

|

| Prince of Nassau-Orange-Fulda | |

| Duke of Oldenburg |

|

| King of Prussia | |

| Archbishop of Regensburg |

|

| Princes of Salm | |

| Grand Duke of Salzburg |

Disbursement of the imperial abbeys, convents and provostries

| Awarded to | Mediatized state |

|---|---|

| France and client states (previously annexed) | |

| Count of Aspremont-Lynden | |

| Margrave of Baden |

|

| Elector of Bavaria | |

| Duke of Breisgau-Modena | |

| Prince of Bretzenheim | |

| Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel | |

| Prince of Dietrichstein |

|

| Prince of Ligne | |

| Prince of Metternich | |

| Prince of Nassau-Orange-Fulda | |

| Count of Ostein | |

| Count of Plettenberg-Wittem | |

| King of Prussia | |

| Count of Quadt | |

| Archbishopric of Regensburg | |

| Order of St. John | |

| Grand Duke of Salzburg | |

| Count of Schaesberg-Retersbeck | |

| Prince of Sinzendorf | |

| Count of Sternberg-Manderscheid | |

| Prince of Thurn and Taxis | |

| Count of Törring-Jettenbach | |

| Count of Waldbott von Bassenheim | |

| Count of Wartenberg | |

| Duke of Württemberg |

|

The only ecclesiastical entities in Germany not abolished in 1803 were:

-

Teutonic Order (abolished in 1810)

Teutonic Order (abolished in 1810) -

Knights of St. John (abolished in 1806)

Knights of St. John (abolished in 1806) -

Archbishopric of Regensburg (abolished in 1805)

Archbishopric of Regensburg (abolished in 1805)

Disbursement of the Free Imperial Cities and villages

| Awarded to | Mediatized state |

|---|---|

| France | |

| Elector of Bavaria |

|

| King of Prussia | |

| Margrave of Baden | |

| Duke of Württemberg | |

| Landgrave of Hesse-Darmstadt | |

| Prince of Nassau-Usingen | |

| Prince of Nassau-Dillenburg | |

| Prince of Bretzenheim |

|

| Count of Quadt | |

| Archbishop of Regensburg |

The only free cities in Germany not abolished in 1803 were:

-

Augsburg (annexed to Bavaria 1806)

Augsburg (annexed to Bavaria 1806) -

Bremen (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814)

Bremen (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814) -

Frankfurt (annexed to Regensburg 1806, restored 1813, annexed to Prussia 1866)

Frankfurt (annexed to Regensburg 1806, restored 1813, annexed to Prussia 1866) -

Hamburg (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814)

Hamburg (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814) -

Lübeck (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814, abolished 1937)

Lübeck (annexed to France 1811, restored 1814, abolished 1937) -

Nuremberg (annexed to Bavaria 1806)

Nuremberg (annexed to Bavaria 1806)

Members of the Imperial Diet mediatised in 1806

States mediatised after 1806

| Mediatized by | Date | Mediatized state |

|---|---|---|

| King of Westphalia | 1807 |

|

| Grand Duke of Berg | 1808 | |

| France | 1810 | |

| Russia (status quo of 1806 restored) | 1813 | |

| Congress of Vienna | 1814 | |

| Bavaria | 1814 |

Restored sovereign states

After being abolished or mediatised, very few states were recreated. Those that were included:

-

Free City of Bremen

Free City of Bremen -

Free City of Frankfurt

Free City of Frankfurt -

Free City of Hamburg

Free City of Hamburg -

Kingdom of Hannover

Kingdom of Hannover -

Electorate of Hesse(-Cassel)

Electorate of Hesse(-Cassel) -

Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg

Landgraviate of Hesse-Homburg -

Free City of Lübeck

Free City of Lübeck -

.svg.png) Grand Duchy of Oldenburg

Grand Duchy of Oldenburg

See also

- List of states in the Holy Roman Empire

- List of Imperial Diet participants (1792)

- Rittersturm, the illegal mediatization of the Imperial Knights

Sources

Texts on Wikisource:

Texts on Wikisource:

- Arenberg, Jean Engelbert. The Lesser Princes of the Holy Roman Empire in the Napoleonic Era. Dissertation, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C., 1950 (later published as Les Princes du St-Empire a l'époque napoléonienne., Louvain: Publications universitaires de Louvain, 1951).

- Gollwitzer, Heinz. Die Standesherren. Die politische und gesellschaftliche Stellung der Mediatisierten 1815–1918. Stuttgart 1957 (Göttingen 1964)

- Reitwiesner, William Addams. "The Meaning of the Word Mediatized".

- Fabianek, Paul: Folgen der Säkularisierung für die Klöster im Rheinland – Am Beispiel der Klöster Schwarzenbroich und Kornelimünster, 2012, Verlag BoD, ISBN 978-3-8482-1795-3

References and notes

- ↑ In the present context, secularization means "the transfer (of property) from ecclesiastical to civil possession or use" (Webster's Encyclopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language, 1989

- ↑ Whaley, J., Germany and the Holy Roman Empire (1493–1806), Oxford University Press, 2011, vol. 2, p. 620.

- ↑ John G. Gagliardo, Germany Under the Old Regime, 1600—1790, Longman Publishing Group, 1991, p. viii)

- ↑ These figures do not include the hundreds of tiny territories of the Imperial Knights, who were immediate vassals of the Emperor and therefore self-ruling.

- ↑ Lens Scales, The Shaping of German Identity. Authority and Crisis, 1245—1414, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 71.

- ↑ Arnold, Count and Bishop in Medieval Germany. A Study of Regional Power, 1100—1350, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1992, pp. 273, 352.

- ↑ Arnold, p. 13.

- ↑ Unlike those, some secularized prince-bishoprics in the north and northeast, such as Brandenburg, Havelberg, Lebus, Meissen, Merseburg, Naumburg-Zeitz, Schwerin and Camin had ceased to exercise independent rights and had effectively become subordinate to powerful neighboring rulers well before the Reformation. Therefore, they had become prince-bishoprics in name only. Joachim Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, Volume I, Maximilian I to the Peace of Westphalia, Oxford University Press, 2012, p. 89.

- ↑ Peter Wilson, The Holy Roman Empire 1495-1806, Studies in European History, Second Edition (2011), pp. 94—95.

- ↑ Derek Beales, Prosperity and Plunder. European Catholic Monasteries in the Age of Revolution, 1650-1815, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 59.

- ↑ Anton Schindling, "The Development of the Eternal Diet in Regensburg", The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 58, Supplement: Politics and Society in the Holy Roman Empire, 1500-1806 (Dec., 1986), p. S66.

- ↑ John Gagliardo, The Holy Roman Empire as Idea and Reality, 1763—1806, Indiana University Press, 1980, p. 196.

- ↑ Joachim Whaley, Germany and the Holy Roman Empire, Volume II, The Peace of Westphalia to the Dissolution of the Reich, Oxford University Press, 2012, pp. 376—377.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 196.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 209.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, pp. 566—568.

- ↑ Agatha Ramm, Germany 1789—1919. A Political History, Methuen & Co., 1967, p. 43.

- ↑ Guillaume de Garden, Histoire générale des traités de paix et autres transactions principales entre toutes les puissances de l'Europe depuis la paix de Westphalie, Volume 5, Paris, Amyot, 1848, pp. 360—361

- ↑ Garden, volume 5, pp. 353—357.

- ↑ Ramm, p. 43.

- ↑ Peter H. Wilson, Bolstering the Prestige of the Habsburgs: The End of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, The International History Review, Vol. 28, No. 4 (Dec., 2006), p. 715. .

- ↑ Gagliardo, pp. 189—190.

- ↑ Gagliardo, pp. 191-192.

- ↑ http://www.napoleon.org/en/reading_room/articles/files/treaty_luneville.asp#ancre5.

- ↑ Peter H. Wilson, Bolstering the Prestige of the Habsburgs: The End of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, p. 715.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 612.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 612.

- ↑ Gagliardo, Reich and Nation, p. 206-209, 214-215.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 214.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 215.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 612.

- ↑ Whaley, pp. 618—619.

- ↑ Gagliardo, pp. 192—193.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 193.

- ↑ Barras, a former prominent member of the Directorate, devoted several pages of his memoirs to the venality of his former protégé Talleyrand and his underlings who allegedly collected 15 million francs in bribes during the compensation process. Manfred Wolf, , Die Entschädigung des Herzogs von Croy im Zusammenhang mit der Säkularisierung des Fürstbistums Münster.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, pp. 619-620.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 193.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 619.

- ↑ Michel Kerautret, Les Allemagnes napoléoniennes.

- ↑ Lars Behrisch, Christian Fieseler, Les cartes chiffrées: l’argument de la superficie à la fin de l’Ancien Régime en Allemagne.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 193.

- ↑ A letter of Talleyrand to Laforest, the head of the French delegation in Regensburg, alludes to millions being paid by, among others, the three Hanseatic Cities (Hamburg, Lübeck, Bremen) Frankfurt and Württemberg. Manfred Wolf, pp. 147—153.

- ↑ Manfred Wolf, pp. 130—131.

- ↑ Der 24. Februar 1803. Reichsdeputationshauptschluß.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 620.

- ↑ Guillaume de Garden, Histoire générale des traités de paix et autres transactions principales entre toutes les puissances de l'Europe depuis la paix de Westphalie, Volume 7, Paris, Amyot, 1848, pp. 148—149.

- ↑ Wilson, pp. 718—719.

- ↑ Garden, vol. 7, p. 143.

- ↑ Günter Dippold, Der Umbruch von 1802/04 im Fürstentum Bamberg., pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Garden, vol. 7, p. 231.

- ↑ Garden, vol. 7, pp. 200, 238.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 193.

- ↑ The Habsburg dynasty’s tenure of the emperorship was not seriously threatened since the Habsburg would control two electoral votes (Bohemia and Salzburg) instead of one (Bohemia), and the key Protestant Electors would effectively neutralize each other: Hanover and Saxony would never contemplate electing a Prussian emperor and vice versa. Whaley, vol. II, p. 628–629.

- ↑ Garden, vol. 7, pp. 381, 388—389.

- ↑ Whaley, 620—621

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 331, note 32

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 194

- ↑ Whaley, p. 620

- ↑ Dippold, p. 34.

- ↑ There were also 5 remaining Reichsdörfer (imperial villages), out of more than 200 in the Middle Ages, that had survived precariously under the Emperor's distant protection. Unlike the imperial cities, they were not represented at the Imperial Diet and in the Circles.

- ↑ Wilson, p. 714—715

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 221—222

- ↑ 1802/03 Das Ende der Reichsstädte Leutkirch,Wangen, Isny, Manuskripte der Vorträge Herausgegeben vom Stadtarchiv Leutkirch, 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ Gagliardo, p. 221

- ↑ For example, the Count of Metternich received compensation in the form of the Abbey of Ochsenhausen, subject however to the obligation to pay a total of 20,000 Gulden in annual pension to three as part of their compensation package: the Count of Aspremont (850 Gulden), the Count of Quadt (11,000 Gulden) and the Count of Wartenberg (8,150 Gulden).Hauptschluß der ausserordentlichen Reichsdeputation vom 25. Februar 1803, §24.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 621.

- ↑ Whaley, vol. II, p. 621.

- ↑ Whaley, J., Germany and the Holy Roman Empire (1493–1806), Oxford University Press, 2011, vol. 2, p. 620.

- ↑ Whaley, p. 623.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Mediatization. |

- (German) Full text, including the preamble

- (German) "The full text of the mediatization". of 25 February 1803

- (English) Report on compensations on which the Final Recess will be based