Lapland War

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

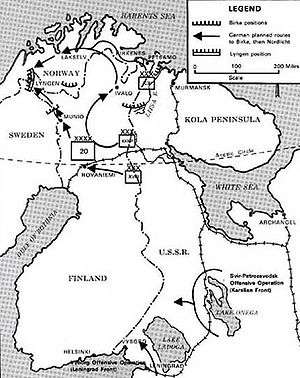

The Lapland War (Finnish: Lapin sota; Swedish: Lapplandskriget; German: Lapplandkrieg) was fought between Finland and Germany from September 1944 to April 1945 in Finland's northernmost Lapland Province. For the Finns, this was a separate conflict, much like the Continuation War. From a German perspective, the retreat through Lapland was part of the Second World War as part of their two campaigns to evacuate northern Finland and northern Norway: Operation Birke and Operation Nordlicht. The Finnish Army was forced to demobilise their forces while at the same time fighting to force the German Army to leave Finland. German forces retreated to Norway, and Finland managed to uphold its obligations under the Moscow Armistice, although it remained formally at war with the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom and the British Dominions until the formal conclusion of the Continuation War was ratified by the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty.

Prelude

Germany and Finland had been at war with the Soviet Union since June 1941, co-operating closely in the Continuation War. However, as early as the summer of 1943, the German High Command began making plans for the eventuality that Finland might make a separate peace agreement with the Soviet Union. The Germans planned to withdraw their forces northward in order to shield the nickel mines near Petsamo.[4]

During the winter of 1943–1944, the Germans improved the roads from northern Norway to northern Finland by extensive use of prisoner of war (POW) labour in certain areas.[5] Casualties among these POWs were high, in part because many of them had been captured in southern Europe and were still in summer uniform. In addition, the Germans surveyed defensive positions and planned to evacuate as much material as possible from the region, and meticulously prepared for withdrawal.[6] On 9 April 1944, the German withdrawal was named "Operation Birke".[6] In June 1944 the Germans started constructing fortifications against an enemy advance from the south.[7] The accidental death of Generaloberst Eduard Dietl on 23 June 1944 brought Generaloberst Lothar Rendulic to the command of the 20th Mountain Army.[8]

A change of Finnish leadership in early August 1944 led the Germans to believe that Finland would try to achieve a separate agreement with the Soviet Union.[9] The Finnish announcement of the ceasefire triggered frantic efforts in the German 20th Mountain Army, which immediately started Operation Birke and other material evacuations from Finland. Large amounts of materiel were evacuated from southern Finland and harsh punishments were set for any hindering of the withdrawal.[10] Finnish forces, which included the 3rd, 6th, and 11th divisions, the armoured division as well as the 15th and Border Jaeger brigades, were moved to face the Germans.

Baltic

On 2 September 1944, after the Finns informed the Germans of the cease fire between Finland and the Soviet Union, the Germans started seizing Finnish shipping. However, since this action resulted in a Finnish decision to not allow ships to sail from Finland to Germany, and nearly doomed the material evacuations of Operation Birke, it was rescinded. After the order was called off, the Finns, in turn, allowed Finnish tonnage to be used to hasten the German evacuations.[11] The first German naval mines were laid in Finnish seaways on 14 September 1944, allegedly for use against Soviet shipping, though since Finland and Germany were not yet in open conflict at the time, the Germans warned the Finns of their intent.[12]

On 15 September 1944, the German Navy tried to seize Hogland island in Operation Tanne Ost. In response, Finland immediately removed its shipping from the joint evacuation operation. The last German convoy departed from Kemi on 21 September 1944 and was escorted by both submarines and in addition (south of Åland) by German cruisers.[13] After the landing attempt, a Finnish coastal artillery fort prevented German netlayers from passing into the Baltic Sea at Utö on 15 September, as they had been ordered to intern the German forces. However, on 16 September, a German naval detachment consisting of the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen escorted by five destroyers, arrived at Utö. The German cruiser stayed out of range of the Finnish 152 mm guns and threatened to open fire with its artillery. In order to avoid bloodshed, the Finns allowed the netlayers to pass.[14]

A Finnish landing operation started on 30 September 1944 when three transport ships (SS Norma, SS Fritz S and SS Hesperus) without escorts departed from Oulu towards Tornio. They arrived on 1 October and managed to disembark their troops without any interference. A second wave of four ships arrived on 2 October and a third wave – three ships strong – managed to disembark with only a single ship being lightly damaged by German dive bombers. On 4 October, bad weather prevented Finnish air cover from reaching Tornio which left the fourth landing wave vulnerable to German Stuka dive bombers which scored several hits sinking SS Bore IX and SS Maininki alongside the pier. The fifth wave on 5 October suffered only light shrapnel damage despite being both shelled from shore and bombed. The first Finnish naval vessels Hämeenmaa, Uusimaa, VMV 15 and VMV 16 arrived with the sixth wave just in time to witness German Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor bombers attacking the shipping at Tornio with Henschel Hs 293 glide bombs without results. Arrival of naval assets allowed the Finns to safely disembark heavy equipment which played an important role during the Battle of Tornio.[15]

Sailors on Finnish ships in German-held ports, including Norway, were interned, and German submarines sank several Finnish civilian vessels. German submarines also had some success against Finnish military vessels, including the sinking of the minelayer Louhi. One important consequence of the Finnish armistice with the Soviet Union was that Soviet naval forces could now circumvent German naval mine barriers on the Gulf of Finland by using the Finnish coastal seaways. This allowed Soviet submarines now based in the Finnish Archipelago to gain access to the German shipping in the southern Baltic Sea.

Lapland

The cease fire agreement between Finland and the Soviet Union required the Finns to break diplomatic ties with Germany and publicly demand the withdrawal of all German troops from Finland by 15 September 1944. Any troops remaining after the deadline were to be disarmed and handed over to the Soviet Union.[16] Even with the massive efforts of the Germans in Operation Birke, this proved impossible, with the Finns estimating it would take the Germans three months to fully evacuate.[17] The task was further complicated by the Soviet demand that the major part of Finland's armed forces be demobilized,[18] even as they attempted to conduct a military campaign against the Germans. With the exception of the inhabitants of the Tornio area, most of the civilian population of Lapland (totaling 168,000 people) was evacuated to Sweden and southern Finland. The evacuation was carried out as a cooperative effort between the German military and Finnish authorities prior to the start of hostilities.[19]

Before deciding to accept the Soviet demands, Finnish President Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim wrote a letter directly to Adolf Hitler:[20]

Our German brothers-in-arms will forever remain in our hearts. The Germans in Finland were certainly not the representatives of foreign despotism but helpers and brothers-in-arms. But even in such cases foreigners are in difficult positions requiring such tact. I can assure you that during the past years nothing whatsoever happened that could have induced us to consider the German troops intruders or oppressors. I believe that the attitude of the German Army in northern Finland towards the local population and authorities will enter our history as a unique example of a correct and cordial relationship ... I deem it my duty to lead my people out of the war. I cannot and I will not turn the arms which you have so liberally supplied us against Germans. I harbour the hope that you, even if you disapprove of my attitude, will wish and endeavour like myself and all other Finns to terminate our former relations without increasing the gravity of the situation.

Autumn maneuvers

As the Finns wanted to avoid devastation to their country, and the Germans wished to avoid hostilities, both sides wanted the evacuation to be performed as smoothly as possible.[21] By 15 September 1944, a secret agreement had been reached by which the Germans would inform the Finns of their withdrawal timetable, who would then allow the Germans to destroy roads, railroads and bridges.[22] In practice, friction soon arose both from the destruction caused by the Germans and from the pressure exerted on the Finns by the Soviets, and there were several incidents between the armies.[23] The Finns deployed their 3rd Division, 11th Division, and 15th Brigade to the coastal area, the 6th and the Armoured divisions to Pudasjärvi, and the Border Jaeger Brigade to the eastern part of the country.

Initial clashes

The first open violence between Finnish forces and the 20th Mountain Army took place 20 km southwest of Pudasjärvi, at around 08:00 on 28 September 1944, when Finnish advance units first issued a surrender demand then opened fire on a small German rearguard contingent.[24] This took the Germans by surprise, as the Finns had previously agreed to warn them should they be forced to take hostile action against them.[24] After the incident partial contact was re-established: the Germans told the Finns they had no interest in fighting them, but would not surrender.[24] The next incident took place on 29 September at a bridge crossing the Olhava river between Kemi and Oulu. Finnish troops, who had been ordered to take the bridge intact, were attempting to disarm explosives rigged to the bridge when the Germans detonated them, demolishing the bridge and killing the Finns' company commander, among others.[25] On 30 September the Finns attempted to encircle the Germans at Pudasjärvi by way of flanking movements through the forests, and managed to cut the road leading north. By then, however, the bulk of the German force at Pudasjärvi had already left, leaving behind only a small detachment which, after warning the Finns, blew up a munitions dump.[26]

Fighting intensified on 1 October 1944, when the Finns launched a risky seaborne invasion near Tornio, on the border with Sweden.[27] The landing had originally been planned as a diversionary raid, with the main assault to take place at Kemi, where the Finnish battalion-sized Detachment Pennanen (Osasto Pennanen) was already in control of important industrial facilities on the island of Ajos. Various considerations – including a far stronger German garrison at Kemi, already alerted by local attacks – made the Finns change the target to Röyttä (Tornio's outer port).[27] The Finns initially landed the 11th Infantry Regiment (JR 11), which, together with a civic guard-led uprising at Tornio, managed to secure both the port and most of the town, as well as the important bridges over the Torne River; however, the attack soon bogged down due to disorganization – some of it caused by alcohol looted from German supply depots – and stiffening resistance. During the ensuing Battle of Tornio the Germans fought hard to retake the town, as it formed an important transportation link between the two roads running parallel to the Kemijoki and Tornionjoki rivers. Their forces initially consisted of Division Kräutler (of roughly reinforced-regiment strength) [28] and were later reinforced with an armoured company (2nd Company of Panzer Abteilung 211), two infantry battalions, and the Machine Gun Ski Brigade Finnland.[29] The Finns reinforced their troops with two infantry regiments (JR 50 and JR 53)[30] and managed to hold the area, beating back several German counterattacks. Heavy combat lasted for a week, until 8 October 1944, when the Germans were finally forced to withdraw.[31]

Meanwhile, Finnish troops were advancing overland from Oulu towards Kemi, with the 15th Brigade making slow progress even in the face of meager German resistance.[32] Their advance was hampered by the efficient destruction of roads and bridges by the withdrawing Germans, as well as a lack of fighting spirit in both Finnish troops and their leaders.[33] The Finns attacked Kemi on 7 October 1944, attempting to encircle the Germans with a frontal attack by the 15th Brigade and an attack from the rear by Detachment Pennanen.[34] Strong German resistance, civilians in the area, and looted alcohol prevented the Finns from fully succeeding in trapping all the Germans. Though Finnish forces took several hundred prisoners, they failed to prevent the Germans from demolishing the important bridges over the Kemijoki river once they began their withdrawal on 8 October.[35]

Further action in the Lapland War

As Allied war efforts against Germany continued, the leadership of the 20th Mountain Army, as well as the OKW, came to believe it would be perilous to maintain positions in Lapland and in northern Norway east of Lyngen, and began preparations for withdrawal. After long delays, Hitler accepted the proposal on 4 October 1944, and it was codenamed "Operation Nordlicht" on 6 October 1944.[36] Instead of a gradual withdrawal from southern Lapland into fortified positions further to the north while evacuating all material, as in Operation Birke, Operation Nordlicht called for a rapid and strictly organized withdrawal directly behind Lyngen Fjord in Norway, while under pressure from harassing enemy forces.[36]

As the Germans withdrew, movement was mostly limited to the immediate vicinity of Lapland's three main roads, which constricted military activities considerably. In general, the actions followed a pattern in which advancing Finnish units would encounter German rearguards and attempt to flank them on foot, the destroyed road network preventing them from bringing up artillery and other heavy weapons. As Finnish riflemen slowly picked their way through the dense woods and marshland, the motorized German units would simply drive away and take up positions further down the road.[37]

Finnish forces began pursuing the Germans. The Finnish 11th Division advanced north from Tornio on the road running along the Torne River while the 3rd Division marched from Kemi towards Rovaniemi. After the 6th and the Armoured divisions linked up at Pudasjärvi, they advanced northward, first towards Ranua and then to Rovaniemi. The Border Jaeger Brigade moved north along the eastern border, depositing border guards as it advanced. Due to the destruction of the road network the Finns were forced to use combat troops for repair work; at times, for example, the entire 15th Brigade was committed to road construction. Finnish forces advancing from Kemi towards Rovaniemi did not see any real action, as Finnish troops on foot were not able to keep up with withdrawing motorized German units; however, on the road leading from Ranua towards Rovaniemi there were several small battles, first at Ylimaa, then Kivitaival, then Rovaniemi. North of Rovaniemi the Finns encountered heavily fortified German schutzwall positions at Tankavaara. On the road running along the Torne and Muonio rivers, the German withdrawal went so smoothly that there was no fighting until the Finnish 11th Division reached the village of Muonio.

At Ylimaa, on 7 October, the Finns captured documents detailing German positions, forcing them to fight a delaying action off their pre-set timetable; however, as the forces were roughly even numerically, the Finnish lack of heavy weapons, and exhaustion from long marches, prevented the Finnish Jaeger Brigade from trapping the defending German 218th Mountain Regiment before it received permission to withdraw, on 9 October.[38] At Kivitaival on 13 October the tables were turned and only a fortuitous withdrawal of the 218th Mountain Regiment saved the Finnish 33rd Infantry Regiment from being severely mauled. The German withdrawal allowed the Finns to surround one of the delaying battalions, but the German 218th Mountain Regiment returned and managed to rescue the stranded battalion.[39] The first Finnish units reaching the vicinity of Rovaniemi were components of the Jaeger Brigade advancing from Ranua on 14 October. The Germans repelled Finnish attempts to capture the last intact bridge over the Kemijoki River and then left the mostly demolished town to the Finns on 16 October 1944.[40]

Finnish demobilization and difficult supply routes began to take their toll, and at Tankavaara barely four battalions of the Finnish Jaeger Brigade attempted, unsuccessfully, to dislodge the German 169th Infantry Division, 12 battalions strong, entrenched in prepared fortifications. Finnish forces first reached the area on 26 October but gained ground only on 1 November, when the Germans withdrew further to the north.[41] At Muonio, on 26 October, the German Kampfgruppe Esch, four battalions, and the 6th SS Mountain Division Nord again had numerical and material superiority in the form of artillery and armour support, which prevented the Finns from gaining the upper hand, despite initially fairly successful flanking operations by the 8th and 50th infantry regiments. The Finnish plan had been to prevent the SS Mountain Division, marching from the direction of Kittilä, from reaching Muonio, and thereby trap it; however, the delaying actions of Kampfgruppe Esch and the destruction of the road network made it impossible for the Finns to reach Muonio before the SS Mountain Division.[42]

German retreat to Norway

For most practical purposes, the war in Lapland ended in early November 1944.[43] In north-eastern Lapland after holding the Finns off at Tankavaara the Germans withdrew swiftly from Finland at Karigasniemi on 25 November 1944. The Finnish Jaeger Brigade pursuing them had by then been depleted in manpower due to demobilization.[44] In northwest Lapland there were on 4 November only four battalions of Finnish troops left and by February 1945 a mere 600 men. The Germans continued their withdrawal but stayed in fortified positions first at Palojoensuu (village ~50 km north of Muonio along the Torne River) in early November 1944 from where they moved further to positions along the Lätäseno River (Sturmbock-Stellung) on 26 November. The German 7th Mountain Division held these positions until 10 January 1945 when northern Norway had been emptied and positions at Lyngen Fjord were manned. Some German positions defending Lyngen extended over the Finnish side of the border, however no real activity took place before the Germans withdrew from Finland on 25 April 1945.[43]

Consequences

From the start of the war the Germans had been systematically destroying and mining the roads and bridges as they withdrew. However, after the first real fighting took place the German commander, General Lothar Rendulic, issued several orders with regards to destroying Finnish property in Lapland. On 6 October a strict order was issued which named only military or militarily important sites as targets. On 8 October, after the result of the fighting in Tornio and the Kemi region became obvious, the Germans made several bombing raids, targeting factory areas of Kemi and inflicting heavy damage on them.[45] However, on 9 October the demolition order was extended to include all governmental buildings with the exception of hospitals.[46] On 13 October, all habitable structures, including barns, though making an exception for hospitals and churches, were ordered to be destroyed north of the line running from Ylitornio via Sinettä (the small village ~20 km NWN of Rovaniemi) to Sodankylä (including the listed settlements) in northern Finland. Though it made sense from the German perspective to do this to deny pursuing forces from getting any shelter it had a very limited effect on the Finns who, unlike the Germans, always carried tents with them and did not require any existing shelter.[46]

At Rovaniemi the Germans initially concentrated mainly on destroying governmental buildings but once fire got loose several more were destroyed. German attempts to fight the fire, however, failed and a train loaded with ammunition caught fire at Rovaniemi railroad station on 14 October resulting in a massive explosion which caused further destruction as well as spreading the fire throughout the primarily wooden buildings of the town. German attempts to fight the fire had failed by the time, on 16 October, they abandoned the now ruined town to the advancing Finns.[47]

In their retreat the German forces under General Lothar Rendulic devastated large areas of northern Finland with scorched earth tactics. As a result, some 40–47% of the dwellings in the area were destroyed, and the provincial capital of Rovaniemi was burned to the ground, as were the villages of Savukoski and Enontekiö. Two-thirds of the buildings in the main villages of Sodankylä, Muonio, Kolari, Salla and Pello were demolished, 675 bridges were blown up, all main roads were mined, and 3,700 km of telephone lines were destroyed.

In addition to the property losses, estimated as equivalent to about US $300 million in 1945 dollars (US$ 3.95 billion in 2016), about 100,000 inhabitants became refugees, a situation that added to the problems of postwar reconstruction. After the war the Allies convicted Rendulic of war crimes, and he was sentenced to 20 years in prison, although charges concerning the devastation of Lapland were dropped. He was released after six years.

The military casualties of the conflict were relatively limited: 774 killed in action (KIA), 262 missing in action (MIA) and about 3,000 wounded in action (WIA) for the Finnish troops, and 1,200 KIA and 2,000 WIA for the Germans. Also, 1,300 German soldiers became prisoners of war, and were handed over to the Soviet Union according to the terms of the armistice with the Soviets.[48] The extensive German land mines caused civilian casualties for decades after the war, and almost 100 personnel were killed during demining operations. Hundreds of Finnish women who had been engaged to German soldiers or working for the German military left with the German troops, meeting diverse fates.[49]

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ Elfvengren, Eero (2005). "Lapin sota ja sen tuhot". In Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti. Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. pp. 1124–1149. ISBN 978-951-0-28690-6.

- ↑ Kurenmaa, Pekka; Lentilä, Riitta (2005). "Sodan tappiot". In Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti. Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. pp. 1150–1162. ISBN 978-951-0-28690-6.

- 1 2 Ahto 1980, p. 296.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 15–20.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, p. 21.

- 1 2 Ahto 1980, pp. 37–41.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, p. 43.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, p. 48, 59–61.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 62–71.

- ↑ Kijanen 1968, p. 220.

- ↑ Kijanen 1968, p. 221.

- ↑ Kijanen 1968, p. 225.

- ↑ Kijanen 1968, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Kijanen 1968, pp. 226–227.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, p. 317.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, p. 327.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, p. 319.

- ↑ Finnish National Broadcasting Company YLE: Evacuation of Lapland Retrieved 2007-02-22. RealAudio Clip. (Finnish)

- ↑ Nenye, Vesa; Munter, Peter; Wirtanen, Toni; Birks, Chris (2016). Finland at War: the Continuation and Lapland Wars 1941–45. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1472815262.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, pp. 337–338.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, pp. 338–339.

- ↑ Lunde 2011, pp. 339–341.

- 1 2 3 Ahto 1980, pp. 142–144.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 146–147.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 148–149.

- 1 2 Ahto 1980, p. 150.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, p. 153.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 166–167, 177, 195.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 177, 195.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 202–207.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 207–210.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 210–211.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 212–213.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 213–214.

- 1 2 Lunde 2011, pp. 342–343, 349.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 230–232.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 232–245.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 245–250.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 268–278.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 280–294.

- 1 2 Ahto 1980, pp. 294–295.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 278–280.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, p. 215.

- 1 2 Ahto 1980, pp. 216–218.

- ↑ Ahto 1980, pp. 219–222.

- ↑ Lapland War Retrieved 2007-02-22

- ↑ Finnish National Broadcasting Company YLE: Naiset saksalaisten matkassa WWW-page and linked RealAudio clip. Retrieved 2007-02-22 (Finnish); Finnish National Broadcasting Company YLE: Paluu miinavaaraan. WWW-page and linked RealAudio clip. Retrieved 2007-02-22 (Finnish); Finnish National Broadcasting Company YLE: Jälleenrakennus WWW-page and linked RealAudio clip. Retrieved 2007-02-22 (Finnish)

Bibliography

- Ahto, Sampo (1980). Aseveljet vastakkain – Lapin sota 1944–1945 [Brothers in arms against each other – Lapland War 1944–1945] (in Finnish). Helsinki: Kirjayhtymä. ISBN 978-951-26-1726-5.

- Kijanen, Kalervo (1968). Suomen Laivasto 1918–1968 II. Helsinki: Meriupseeriyhdistys/Otava.

- Leskinen, Jari; Juutilainen, Antti, eds. (2005). Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen (in Finnish) (1st ed.). Werner Söderström Osakeyhtiö. ISBN 978-951-0-28690-6.

- Lunde, Henrik O. (2011). Finland's War of Choice: The Troubled German-Finnish Alliance in World War II. Newbury: Casemate Publishers. ISBN 978-1-61200-037-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lapland War. |