Invasion of Normandy

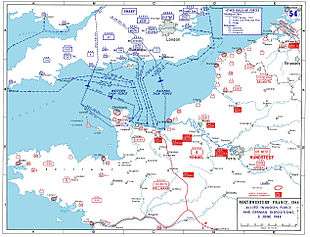

The Western Allies of World War II launched the largest amphibious invasion in history when they assaulted Normandy, located on the northern coast of France, on 6 June 1944. The invaders were able to establish a beachhead as part of Operation Overlord after a successful "D-Day," the first day of the invasion.

Allied land forces came from the United States, Britain, Canada, and Free French forces. In the weeks following the invasion, Polish forces and contingents from Belgium, Czechoslovakia, Greece and the Netherlands participated in the ground campaign; most also provided air and naval support alongside elements of the Royal Australian Air Force, the Royal New Zealand Air Force, and the Royal Norwegian Navy.[4][nb 1][1]

The Normandy invasion began with overnight parachute and glider landings, massive air attacks and naval bombardments. In the early morning, amphibious landings on five beaches codenamed Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah began and during the evening the remaining elements of the airborne divisions landed. Land forces used on D-Day sailed from bases along the south coast of England, the most important of these being Portsmouth.[5]

Planning

Allied forces rehearsed their D-Day roles for months before the invasion. On 28 April 1944, in south Devon on the English coast, 749 U.S. soldiers and sailors were killed when German torpedo boats surprised one of these landing exercises, Exercise Tiger.[6]

In the months leading up to the invasion, the Allied forces conducted a deception operation, Operation Fortitude, aimed at misleading the Germans with respect to the date and place of the invasion.

There were several leaks prior to or on D-Day. Through the Cicero affair, the Germans obtained documents containing references to Overlord, but these documents lacked all detail.[7] Double Cross agents, such as the Spaniard Juan Pujol (code-named Garbo), played an important role in convincing the German High Command that Normandy was at best a diversionary attack. U.S. Major General Henry Miller, chief supply officer of the US 9th Air Force, during a party at Claridge's Hotel in London complained to guests of the supply problems he was having but that after the invasion, which he told them would be before 15 June, supply would be easier. After being told, Eisenhower reduced Miller to lieutenant colonel [Associated Press, June 10, 1944] and sent him back to the U.S. where he retired.[8] Another such leak was General Charles de Gaulle's radio message after D-Day. He, unlike all the other leaders, stated that this invasion was the real invasion. This had the potential to ruin the Allied deceptions Fortitude North and Fortitude South. In contrast, Gen. Eisenhower referred to the landings as the initial invasion.

Only ten days each month were suitable for launching the operation: a day near the full moon was needed both for illumination during the hours of darkness and for the spring tide, the former to illuminate navigational landmarks for the crews of aircraft, gliders and landing craft, and the latter to expose defensive obstacles placed by the German forces in the surf on the seaward approaches to the beaches. A full moon occurred on 6 June. Allied Expeditionary Force Supreme Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower had tentatively selected 5 June as the date for the assault. The weather was fine during most of May, but deteriorated in early June. On 4 June, conditions were clearly unsuitable for a landing; wind and high seas would make it impossible to launch landing craft from larger ships at sea, low clouds would prevent aircraft finding their targets. The Allied troop convoys already at sea were forced to take shelter in bays and inlets on the south coast of Britain for the night.

It seemed possible that everything would have to be cancelled and the troops returned to their embarkation camps (which would be almost impossible, as the enormous movement of follow-up formations into them was already proceeding).[9] The next full moon period would be nearly a month away. At a vital meeting on 5 June, Eisenhower's chief meteorologist (Group Captain J.M. Stagg) forecast a brief improvement for 6 June.[10] Commander of all land forces for the invasion General Bernard Montgomery and Eisenhower's Chief of Staff General Walter Bedell Smith wished to proceed with the invasion. Commander of the Allied Air Forces Air Chief Marshal Leigh Mallory was doubtful, but Allied Naval Commander-in-Chief Admiral Bertram Ramsay believed that conditions would be marginally favorable.[9] On the strength of Stagg's forecast, Eisenhower ordered the invasion to proceed.[11] As a result, prevailing overcast skies limited Allied air support, and no serious damage would be done to the beach defences on Omaha and Juno.[12]

The Germans meanwhile took comfort from the existing poor conditions, which were worse over Northern France than over the English Channel itself, and believed no invasion would be possible for several days. Some troops stood down and many senior officers were away for the weekend. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel took a few days' leave to celebrate his wife's birthday,[13] while dozens of division, regimental and battalion commanders were away from their posts conducting war games just prior to the invasion.[14]

Codenames

The Allies assigned codenames to the various operations involved in the invasion. Overlord was the name assigned to the establishment of a large-scale lodgement on the northern portion of the Continent. The first phase, the establishment of a secure foothold, was codenamed Neptune. According to the D-day museum:

- The armed forces use codenames to refer to the planning and execution of specific military operations. Operation Overlord was the codename for the Allied invasion of northwest Europe. The assault phase of Operation Overlord was known as Operation Neptune. (…) Operation Neptune began on D-Day (6 June 1944) and ended on 30 June 1944. By this time, the Allies had established a firm foothold in Normandy. Operation Overlord also began on D-Day, and continued until Allied forces crossed the River Seine on 19 August 1944.[15]

Officers with knowledge of D-Day were not to be sent where there was the slightest danger of being captured. These officers were given the codename of "Bigot", derived from the words "To Gib" (To Gibraltar) that was stamped on the papers of officers who took part in the North African invasion in 1942.[16] On the night of 27 April, during Exercise Tiger, a pre-invasion exercise off the coast of Slapton Sands beach, several American LSTs were attacked by German E boats and among the 638 Americans killed in the attack and a further 308 killed by friendly fire, ten "Bigots" were listed as missing. As the invasion would be cancelled if any were captured or unaccounted for, their fate was given the highest priority and eventually all ten bodies were recovered.

Allied order of battle

D-Day

The following major units were landed on D-Day (6 June 1944). A more detailed order of battle for D-Day itself can be found at Normandy landings.

- British 6th Airborne Division.[17]

- British I Corps, 3rd British Infantry Division and the British 27th Armoured Brigade.

- 3rd Canadian Infantry Division, 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade

- British XXX Corps, British 50th Infantry Division and British 8th Armoured Brigade.[18]

- British 79th Armoured Division

- U.S. V Corps, U.S. 1st Infantry Division and U.S. 29th Infantry Division.[17][19]

- U.S. VII Corps, U.S. 4th Infantry Division,[19] U.S. 101st Airborne Division,[19] U.S. 82nd Airborne Division.[19][20][21]

The total number of troops landed on D-Day was around 130,000[22]–156,000[23] roughly half American and the other from the Commonwealth Realms.

Subsequent days

The total troops, vehicles and supplies landed over the period of the invasion were:

- By the end of 11 June (D + 5), 326,547 troops, 54,186 vehicles and 104,428 tons of supplies.[23]

- By 30 June (D+24) over 850,000 men, 148,000 vehicles, and 570,000 tons of supplies.[22]

- By 4 July one million men had been landed.[24]

Naval participants

The invasion fleet was drawn from eight different navies, comprising 6,939 vessels: 1,213 warships, 4,126 transport vessels (landing ships and landing craft), and 736 ancillary craft and 864 merchant vessels.[17]

The overall commander of the Allied Naval Expeditionary Force, providing close protection and bombardment at the beaches, was Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay. The Allied Naval Expeditionary Force was divided into two Naval Task Forces: Western (Rear-Admiral Alan G Kirk) and Eastern (Rear-Admiral Sir Philip Vian).

The warships provided cover for the transports against the enemy—whether in the form of surface warships, submarines, or as an aerial attack—and gave support to the landings through shore bombardment. These ships included the Allied Task Force "O".

German order of battle

The number of military forces at the disposal of Nazi Germany reached its peak during 1944. Tanks on the east front peaked at 5,202 in November 1944, while total aircraft in the Luftwaffe inventory peaked at 5,041 in December 1944. By D-Day 157 German divisions were stationed in the Soviet Union, 6 in Finland, 12 in Norway, 6 in Denmark, 9 in Germany, 21 in the Balkans, 26 in Italy and 59 in France, Belgium and the Netherlands.[25] However, these statistics are somewhat misleading since a significant number of the divisions in the east were depleted; German records indicate that the average personnel complement was at about 50% in the spring of 1944.[26]

A more detailed order of battle for D-Day itself can be found at Normandy landings.

Atlantic Wall

Standing in the way of the Allies was the English Channel, a crossing which had frustrated the ambitions of the Spanish Armada and Napoleon Bonaparte's Navy. Compounding the invasion efforts was the extensive Atlantic Wall, ordered by Hitler in his Directive 51. Believing that any forthcoming landings would be timed for high tide (this caused the landings to be timed for low tide), Hitler had the entire wall fortified with tank top turrets and extensive barbed wire, and laid a million mines to deter landing craft. The sector that was attacked was guarded by four divisions.

Divisional areas

The following units were deployed in a static defensive mode in the areas of the actual landings:

- 716th Infantry Division (Static) consisted mainly of those 'unfit for active duty' and released prisoners.

- 352nd Infantry Division, a well-trained unit containing combat veterans.

- 91st Air Landing Division (Luftlande – air transported), a regular infantry division, trained, and equipped to be transported by air.

- 709th Infantry Division (Static). Like the 716th, this division included a number of "Ost" battalions who were led by German personnel.

Adjacent divisional areas

Other divisions occupied the areas around the landing zones, including:

- 243rd Infantry Division (Static), (Generalleutnant Heinz Hellmich). This coastal defense division protected the western coast of the Cotentin Peninsula.

- 920th Infantry Regiment (two battalions)

- 921st Infantry Regiment

- 922nd Infantry Regiment.

- 711th Infantry Division (Static) (Generalleutnant Josef Reichert). This division defended the western part of the Pays de Caux.

- 731st Infantry Regiment

- 744th Infantry Regiment.

- 30th Mobile Brigade (Oberstleutnant Freiherr von und zu Aufsess), comprising three bicycle battalions.

Armoured reserves

Rommel's defensive measures were frustrated by a dispute over armoured doctrine. In addition to his two army groups, Rundstedt also commanded the headquarters of Panzer Group West under General Leo Geyr von Schweppenburg (usually referred to as "von Geyr"). This formation was nominally an administrative HQ for Rundstedt's armoured and mobile formations, but it was later to be brought into the line in Normandy and renamed Fifth Panzer Army. Geyr and Rommel disagreed over the deployment and use of the vital Panzer divisions.

Rommel recognised that the Allies would possess air superiority and would be able to harass his movements from the air. He therefore proposed that the armoured formations be deployed close to the invasion beaches. In his words, it was better to have one Panzer division facing the invaders on the first day, than three Panzer divisions three days later when the Allies would already have established a firm beachhead. Geyr argued for the standard doctrine that the Panzer formations should be concentrated in a central position around Paris and Rouen, and deployed en masse against the main Allied beachhead when this had been identified.

The argument was eventually brought before Hitler for arbitration. He characteristically imposed an unworkable compromise solution. Only three Panzer divisions were given to Rommel, too few to cover all the threatened sectors. The remainder, nominally under Geyr's control, were actually designated as being in "OKW Reserve". Only three of these were deployed close enough to intervene immediately against any invasion of Northern France; the other four were dispersed in southern France and the Netherlands. Hitler reserved to himself the authority to move the divisions in OKW Reserve, or commit them to action. On 6 June many Panzer division commanders were unable to move because Hitler had not given the necessary authorisation, and his staff refused to wake him upon news of the invasion.

Army Group B reserve

- 21st Panzer Division (Generalmajor Edgar Feuchtinger), was deployed near Caen as a mobile striking force as part of the Army Group B reserve. However, Rommel placed it so close to the coastal defenses that, under standing orders in case of invasion, several of its infantry and anti-aircraft units would come under the orders of the fortress divisions on the coast, reducing the effective strength of the division.

The other two armoured divisions over which Rommel had operational control, the 2nd Panzer Division and 116th Panzer Division, were deployed near the Pas de Calais in accordance with German views about the likely Allied landing sites. Neither was moved from the Pas de Calais for at least fourteen days after the invasion.

OKW reserve

The other mechanized divisions capable of intervening in Normandy were retained under the direct control of the German Armed Forces HQ (OKW) and were initially denied to Rommel:

Four divisions were deployed to Normandy within seven days of the invasion:

- 12th SS Panzer Division Hitlerjugend (Brigadeführer Fritz Witt) was stationed to the southeast. Its officers and NCOs (this division had a very weak core of NCOs in Normandy with only slightly more than 50% of its authorised strength[27]) were long-serving veterans, but the junior soldiers had all been recruited directly from the Hitler Youth movement at the age of seventeen in 1943. It was to acquire a reputation for ferocity and war crimes in the coming battle.

- Panzer-Lehr-Division (Generalmajor Fritz Bayerlein). Further to the southwest was an elite unit, originally formed by amalgamating the instructing staff at various training establishments. Not only were its personnel of high quality, but the division also had unusually high numbers of the latest and most capable armoured vehicles.

- 1st SS Panzer Division Leibstandarte SS Adolf Hitler was refitting in Belgium on the Netherlands border after being decimated on the Eastern Front.

- 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division Götz von Berlichingen (Oberführer Werner Ostendorff) was based on Thouars, south of the Loire River, and although equipped with Assault guns instead of tanks and lacking in other transport (such that one battalion each from the 37th and 38th Panzergrenadier Regiments moved by bicycle), it provided the first major counterattack against the American advance at Carentan on 13 June.

Three other divisions (the 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich, which had been refitting at Montauban in Southern France, and the 9th SS Panzer Division Hohenstaufen and 10th SS Panzer Division Frundsberg which had been in transit from the Eastern Front on 6 June), were committed to battle in Normandy around twenty-one days after the first landings.

One more armoured division (the 9th Panzer Division) saw action only after the American breakout from the beachhead. Two other armoured divisions which had been in the west on 6 June (the 11th Panzer Division and 19th Panzer Division) did not see action in Normandy.

Landings

Allied establishment in France

The Allied invasion plans had called for the capture of Saint-Lô, Caen, and Bayeux on the first day, with all the beaches linked except Utah, and Sword (the last linked with paratroopers) and a front line 10 to 16 kilometres (6–10 mi) from the beaches. However, practically none of these objectives had been achieved. It took six weeks for British and Canadian troops to capture Caen, as they faced 7 heavy Panzer divisions, while their American allies, although advancing more rapidly, faced only 2 of these divisions. Overall the casualties had not been as heavy as some had feared (around 10,000 compared to the 20,000 Churchill had estimated) and the bridgeheads had withstood the expected counterattacks.

Once the beachhead was established, two artificial Mulberry harbours were towed across the English Channel in segments and made operational around D+3 (9 June). One was constructed at Arromanches by British forces, the other at Omaha Beach by American forces. By 19 June, when severe storms interrupted the landing of supplies for several days and destroyed the Omaha harbour, the British had landed 314,547 men, 54,000 vehicles, and 102,000 tons of supplies, while the Americans put ashore 314,504 men, 41,000 vehicles, and 116,000 tons of supplies.[28] Around 9,000 tons of materiel were landed daily at the Arromanches harbour until the end of August 1944, by which time the port of Cherbourg had been secured by the Allies and had begun to return to service.

In addition, with the installation of PLUTO in August 1944 the Allies had fuel piped over directly from England without having to rely on vulnerable tankers.

Assessment of the battle

The Normandy landings were the first successful opposed landings across the English Channel in over eight centuries. They were costly in terms of men, but the defeat inflicted on the Germans was one of the largest of the war. Strategically, the campaign led to the loss of the German position in most of France and the secure establishment of a new major front. In larger context the Normandy landings helped the Soviets on the Eastern Front, who were facing the bulk of the German forces and, to a certain extent, contributed to the shortening of the conflict there.

Although there was a shortage of artillery ammunition, at no time were the Allies critically short of any necessity. This was a remarkable achievement considering they did not hold a port until Cherbourg fell. By the time of the breakout the Allies also enjoyed a considerable superiority in numbers of troops (approximately 7:2) and armoured vehicles (approximately 4:1) which helped overcome the natural advantages the terrain gave to the German defenders.

Allied intelligence and counterintelligence efforts were successful beyond expectations. The Operation Fortitude deception before the invasion kept German attention focused on the Pas de Calais, and indeed high-quality German forces were kept in this area, away from Normandy, until July. Prior to the invasion, few German reconnaissance flights took place over Britain, and those that did saw only the dummy staging areas. Ultra decrypts of German communications had been helpful as well, exposing German dispositions and revealing their plans such as the Mortain counterattack.

Allied air operations also contributed significantly to the invasion, via close tactical support, interdiction of German lines of communication (preventing timely movement of supplies and reinforcements—particularly the critical Panzer units), and rendering the Luftwaffe ineffective in Normandy.[nb 2] Although the impact upon armoured vehicles was less than expected, air activity intimidated these units and cut their supplies.

Despite initial heavy losses in the assault phase, Allied morale remained high. Casualty rates among all the armies were tremendous, and the Commonwealth forces had to use a recently created category—Double Intense—to be able to describe them.

German leadership

German commanders at all levels failed to react to the assault phase in a timely manner. Communications problems exacerbated the difficulties caused by Allied air and naval firepower. Local commanders also seemed incapable of the task of fighting an aggressive defense on the beach, as Rommel had envisioned.

The German High Command remained fixated on the Calais area, and von Rundstedt was not permitted to commit the armoured reserve. When it was finally released late in the day, any chance of success was much more difficult. Overall, despite considerable Allied material superiority, the Germans kept the Allies bottled up in a small beachhead for nearly two months, aided immeasurably by terrain factors.

Although there were several known disputes among the Allied commanders, their tactics and strategy were essentially determined by agreement between the main commanders. By contrast, the German leaders were bullied and their decisions interfered with by Hitler, controlling the battle from a distance with little knowledge of local conditions. Field Marshals von Rundstedt and Rommel repeatedly asked Hitler for more discretion but were refused. Von Rundstedt was removed from his command on 29 June after he bluntly told the Chief of Staff at Hitler's Armed Forces HQ (Field Marshal Keitel) to "Make peace, you idiots!" Rommel was severely injured by Allied aircraft on 17 July.

The German commanders also suffered in the quality of the available troops. Sixty thousand of the 850,000 in Rundstedt's command were raised from the many prisoners of war captured on the Eastern Front.[29] These "Ost" units had volunteered to fight against Stalin, but when instead unwisely used to defend France against the Western Allies, ended up being unreliable. Many surrendered or deserted at the first available opportunity.

War memorials and tourism

The beaches at Normandy are still referred to on maps and signposts by their invasion codenames. There are several vast cemeteries in the area. The American cemetery, in Colleville-sur-Mer, contains row upon row of identical white crosses and Stars of David, immaculately kept, commemorating the American dead. Commonwealth graves, maintained in many locations by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, uses white headstones engraved with the person's religious or medal (Victoria Cross or George Cross only) symbol and their unit insignia. The Bayeux War Cemetery, with 4,648 burials, is the largest British cemetery of the war.[30] The largest cemetery in Normandy is the La Cambe German war cemetery, with 21,222 burials, which features granite stones almost flush with the ground and groups of low-set crosses. There is also a Polish cemetery.

At the Bayeux Memorial, a monument erected by Britain has a Latin inscription on the memorial reads "Nos a gulielmo victi victoris patriam liberavimus" – freely translated, this reads "We, once conquered by William, have now set free the Conqueror's native land".[30]

Streets near the beaches are still named after the units that fought there, and occasional markers commemorate notable incidents. At significant points, such as Pointe du Hoc and Pegasus Bridge, there are plaques, memorials or small museums. The Mulberry harbour still sits in the sea at Arromanches. In Sainte-Mère-Église, a dummy paratrooper hangs from the church spire. On Juno Beach, the Canadian government has built the Juno Beach Information Centre, commemorating one of the most significant events in Canadian military history.

In England the most significant memorial is the D-Day Museum in Southsea, Hampshire. The Museum was opened in 1984 to commemorate the 40th anniversary of D-Day. Its centrepiece is the Overlord embroidery commissioned by Lord Dulverton of Batsford (1915–92) as a tribute to the sacrifice and heroism of those men and women who took part in Operation Overlord.

On 5 June 1994 a drumhead service was held on Southsea Common adjacent the D-Day Museum. This service was attended by US President Bill Clinton, Queen Elizabeth II and over 100,000 members of the public.

Dramatisations

The Battle of Normandy has been the topic of many films, television shows, songs, computer games and books. Many dramatisations focus on the initial landings, and these are covered at Normandy Landings. Some examples that cover the wider battle include:

- Films

- Le Bataillon du ciel (sky's battalion), a 1947 French film directed by Alexandre Esway based on the book of Joseph Kessel: Free French SAS paratroopers (Special Air Service) in Brittany from 5 June to August 1944.

- The Longest Day, a 1962 film based on the book of the same name by Cornelius Ryan

- The Americanization of Emily, a 1964 film written by Paddy Chayefsky, directed by Arthur Hiller and starring James Garner and Julie Andrews.

- Overlord, a 1975 black-and-white film written and directed by Stuart Cooper, set around the D-Day invasion.

- The Big Red One, a 1980 film directed by Samuel Fuller and starring Lee Marvin.

- Un jour avant l'aube (One day before dawn), a 1994 French television film directed by Jacques Ertaud: Free French SAS in Brittany.

- Saving Private Ryan, a 1998 Academy Award-winning American film directed by Steven Spielberg and starring Tom Hanks and Matt Damon.

- Band of Brothers, a 2001 American miniseries produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks based on the book of the same name by Stephen Ambrose.

- Ike: Countdown to D-Day, a 2004 American television film directed by Robert Harmon and written by Lionel Chetwynd which emphasizes the difficult decisions General Dwight D. Eisenhower had to make, while dealing with the varied personalities of his direct subordinates, in order to lead Operation Overlord.

- My Way, a 2011 South Korean war film by Kang Je-gyu, starring Jang Dong-gun along with Japanese actor Joe Odagiri and Chinese actress Fan Bingbing.

Notes

- Footnotes

- 1 2 Defence against a mass U-boat attack relied on "19 Group of [RAF] Coastal Command … [it] included one Czech, one Polish, one New Zealander, two Australian and three Canadian squadrons. Even the RAF's own 224 Squadron was a mixed bag of nationalities with 137 Britons, forty-four Canadians, thirty-three Anzacs, two Americans, a Swiss, a Chilean, a South African and a Brazilian" [31] "The D-Day air offensive was another [RAF] multinational operation. It included five New Zealander, seven Australian, twenty-eight Canadian, one Rhodesian, six French, fourteen Polish, three Czech, two Belgian, two Dutch and two Norwegian squadrons" [32] At 05:37 the Norwegian destroyer Sevenner, one of 37 destroyers in the Eastern Task Force, was sunk by a torpedo launched from a German E-boat .[33] "In addition to the Cruiser ORP Dragon, the Polish destroyers ORP Krakowiak and Slazak took part in beach support operations, while the destroyers OKP Blyskewica and Piorun were employed as part of the covering force" [34]

- ↑ Following Normandy, a joke regarding their lack of air support became common and widely spread by Wehrmacht soldiers: "If the plane in the sky is silver, it's American, if it's blue, it's British, if it's invisible, it's ours!"

- Citations

- 1 2 "Title: The Norwegian Navy in the Second World War". Resdal. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- 1 2 3 Tamelander, M, Zetterling, N (2004), Avgörandes Ögonblick: Invasionen i Normandie. Norstedts Förlag, p. 295

- ↑ Zetterling 2000, p. 32.

- ↑ Williams, Jeffery (1988). The long left flank: the hard fought way to the Reich, 1944–1945. London: Cooper. p. . ISBN 0-85052-880-1.

- ↑ Keegan 1989.

- ↑ Small, Ken; Rogerson, Mark (1988). The Forgotten Dead – Why 946 American Servicemen Died Off The Coast Of Devon In 1944 – And The Man Who Discovered Their True Story. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 0-7475-0309-5.

- ↑ Keegan 1989, p. 279.

- ↑ F Pogue, The Supreme Command, Department of the Army, 1954, pp. 163–64

- 1 2 Wilmot, p. 225

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 224

- ↑ Wilmot, p. 226

- ↑ Juno Beach from The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ "D-Day, People & Events: Erwin Rommel (1891–1944)". American Experience, PBS. Retrieved 5 June 2009.

- ↑ David White; Daniel P. Murphy. "The Normandy Invasion". netplaces. The New York Times Company. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "D-Day and the Battle of Normandy: Your Questions Answered". D-Day Museum. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- ↑ Untold Stories of D-Day, National Geographic, June 2002.

- 1 2 3 Keegan, John. "Britannica guide to D-Day 1944". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- ↑ Keegan, John. "Britannica guide to D-Day 1944". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 October 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 Map 81, M.R.D. Foot; I.C.B. Dear, eds. (2005). The Oxford Companion to World War II. Oxford University Press. p. 663. ISBN 978-0-19-280666-6.

- ↑ Bradley, John H. (2002). The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean. Square One Publishers. p. 290. ISBN 0-7570-0162-9. Retrieved 16 November 2007.

- ↑ Patrick Elie – Normandie – France. "D-Day : Normandy 1944 – UTAH BEACH : U.S. Troops". 6juin1944.com. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- 1 2 D-Day 6 June 1944 Archived 9 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Frequently Asked Questions for D-Day and the Battle of Normandy". Ddaymuseum.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ↑ "HyperWar: The War in Western Europe: Part 1 (June to December, 1944) [Chapter 3]". Ibiblio.org. Retrieved 2012-08-25.

- ↑ Wilmot 1997.

- ↑ Tippelskirch, Kurt von, Gechichte der Zweiten Weltkrieg. 1956

- ↑ Zetterling 2000, p. 350.

- ↑ Pogue, Forrest C. (1954). "The Supreme Command,". United States Army in World War II: European Theater of Operations. Washington D.C.: CMH Publication 7–1, Office of the chief of military history, Department of the Army.

- ↑ Keegan 1994, p. 61.

- 1 2 Reed, Paul. "Normandy War Cemeteries: Bayeux Memorial". Battlefields of WW2 website. Retrieved 10 October 2008.

- ↑ Beevor 2009, p. 76.

- ↑ Beevor 2009, p. 77.

- ↑ Beevor 2009, p. 82.

- ↑ Beevor 2009, p. 82 footnotes.

References

- Beevor, Antony (2009). D-Day:The Battle for Normandy (First ed.). London: Viking an imprint of Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-670-88703-3.

- Keegan, John (1994) [1982]. Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-023542-6.

- Keegan, John (1989). The Second World War. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-174011-8..

- Wilmot, Chester (1997) [1952]. The Struggle For Europe. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth Editions. ISBN 1-85326-677-9.

- Zetterling, Niklas (2000). Normandy 1944: German Military Organisation, Combat Power and Organizational Effectiveness. Winnipeg: J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing. ISBN 0-921991-56-8..

Further reading

- Stephen Ambrose. D-Day June 6, 1944: The Climactic Battle of World War II. New york: Simon & Schuster, 1995. ISBN 0-671-88403-4.

- Stephen Badsey, Normandy 1944: Allied Landings and Breakout. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 1990. ISBN 978-0-85045-921-0.

- Carlo D'Este, Decision in Normandy: The Unwritten Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign. London: William Collins Sons, 1983. ISBN 0-00-217056-6.

- M. R. D. Foot, SOE: An Outline History of the Special Operations Executive 1940–46.. BBC Publications, 1984. ISBN 0-563-20193-2.

- Ken Ford, D-Day 1944 (3): Sword Beach & the British Airborne Landings. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84176-366-8.

- Ken Ford, D-Day 1944 (4): Gold & Juno Beaches. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2002. ISBN 978-1-84176-368-2.

- John Herington, Air Power Over Europe, 1944–1945, 1st edition (Official History of Australia in the Second World War Volume IV). Canberra: Australian War Memorial 1963.

- Holderfield, Randal J., and Michael J. Varhola. D-Day: The Invasion of Normandy, June 6, 1944. Mason City, Iowa: Savas Publishing, 2001. ISBN 1-882810-45-7, ISBN 1-882810-46-5.

- Kershaw, Alex. The Bedford Boys: One American Town's Ultimate D-Day Sacrifice. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2003. ISBN 0-306-81355-6.

- "Morning: Normandy Invasion (June–August 1944)". The World at War episode 17. British Broadcasting Corporation. 1974.

- Neillands, Robin. The Battle of Normandy, 1944. London: Cassell, 2002. ISBN 0-304-35837-1.

- Rozhnov, Konstantin. Who won World War II?. BBC News, 5 May 2005.

- Stacey, C.P. Canada's Battle in Normandy: The Canadian Army's Share in the Operations, 6 June – 1 September 1944. Ottawa: King's Printer, 1946.

- Stacey, C.P. Official History of the Canadian Army in the Second World War: Volume III. The Victory Campaign, The Operations in North-West Europe 1944–1945. Ottawa: Department of National Defence, 1960.

- Tute, Warren, John Costello, Terry Hughes. D-Day. London: Pan Books Ltd, 1975. ISBN 0-330-24418-3.

- Whitlock, Flint. The Fighting First: The Untold Story of The Big Red One on D-Day. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8133-4218-X.

- Zaloga, Steven J. D-Day 1944 (1): Omaha Beach. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-1-84176-367-5.

- Zaloga, Steven J. D-Day 1944 (2): Utah Beach & the US Airborne Landings. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2004. ISBN 978-1-84176-365-1.

- Zaloga, Steven J. Operation Cobra 1944: Breakout from Normandy. Botley, Oxford: Osprey Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-1-84176-296-8.

- Numerous volumes in the U.S. Army in World War II series, produced by the United States Army Center of Military History, Gordon A. Harrison, Cross-Channel-Attack (1951), remains a basic source, but several other studies bear heavily upon the operation. They include:

- Robert W. Coakley and Richard M. Leighton, Global Logistics and Strategy (1968);

- Martin Blumenson, Breakout and Pursuit (1961);

- Forrest C. Pogue, The Supreme Command (1954);

- Roland G. Ruppenthal, Logistical Support of the Armies (1953); and

- Graham A. Cosmas and Albert E. Cowdrey, The Medical Department: Medical Service in the European Theater of Operations (1992).

- The Historical Division of the War Department produced three volumes on the event. All have been reprinted by the Center of Military History. Classified as the American Forces in Action series, they are:

- OMAHA Beachhead (1989);

- UTAH Beach to Cherbourg (1990); and

- St. Lo (1984).

- The British Government following the war also issued an official history of the British involvement in the war to be researched and published, the final result being the massive series known as History of the Second World War. The following cover the Normandy Campaign:

- Major L. F. Ellis, Victory in the West: The Battle of Normandy, Official Campaign History v. I (History of the Second World War: United Kingdom Military), Naval & Military Press Ltd; New Ed edition (Sep 2004)., 1-84574-058-0

- Michael Howard, British Intelligence in the Second World War: Volume 5, Strategic Deception, Cambridge University Press (26 October 1990). ISBN 0-521-40145-3 (Series edited by F. H. Hinsley)

- Grand Strategy, Volume 5: August 1943 – September 1944, 1956

- Numerous abbreviated histories have been written. Among the most useful are:

- Charles MacDonald, The Mighty Endeavor: American Armed Forces in the European Theater in World War II (1969); and

- Charles MacDonald and Martin Blumenson, "Recovery of France", in Vincent J. Esposito, ed., A Concise History of World War II (1965).

- Memoirs by Allied commanders contain considerable information. Among the best are:

- Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier's Story (1951);

- Omar N. Bradley and Clay Blair, A General's Life (1983);

- Dwight D. Eisenhower, Crusade in Europe (1948);

- Sir Bernard Law Montgomery of Alamein, Normandy to the Baltic (1948);

- Sir Bernard Law Montgomery of Alamein, The Memoirs of Field Marshal the Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, K.G., Collins (1958). and

- Sir Frederick Edgeworth Morgan, Overture to Overlord (1950).

- Memoirs by Allied and German soldiers of various ranks also give a good insight into the campaign.

- Kurt Meyer, Grenadiers, Stackpole Books,U.S., New Ed edition (15 May 2005)., ISBN 0-8117-3197-9

- Stuart Hills, By Tank Into Normandy, Cassell military; New Ed edition (11 September 2003)., 0-30436-640-4

- Hans von Luck, Panzer Commander: The Memoirs of Colonel Hans von Luck, Cassell military; New Ed edition (9 March 2006)., ISBN 0-304-36401-0

- Almost as useful are biographies of leading commanders. Among the most prominent are:

- Stephen E. Ambrose, The Supreme Commander: The War Years of General Dwight D. Eisenhower (1970), and Eisenhower, Soldier, General of the Army, President-Elect, 1890–1952 (1983);

- Nigel Hamilton, Master of the Battlefield: Monty's War Years, 1942–1944 (1983);

- Richard Lamb, Montgomery in Europe, 1943–1945: Success or Failure (1984);

- Nigel Hamilton, "Montgomery, Bernard Law" in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-19-861411-X, ISBN 0-19-861351-2.

- Ronald Lewin, Rommel as Military Commander (1968).

- B. H. Liddell Hart, The Rommel Papers (section on Normandy written by Lt.Gen Fritz Bayerlein)

- Hans Speidel, Invasion 1944: Rommel and the Normandy Campaign. Chicago: Henry Regnery (1950) (Speidel was Rommel's chief of staff).

- Numerous general histories also exist, many centering on the controversies that continue to surround the campaign and its commanders. See, in particular:

- John Colby, War From the Ground Up: The 90th Division in World War II (1989);

- Carlo D'Este, Decision in Normandy: The Unwritten Story of Montgomery and the Allied Campaign (1983);

- Max Hastings, Overlord, D-Day, June 6, 1944 (1984);

- John Keegan, Six Armies in Normandy: From D-Day to the Liberation of Paris (1982);

- Robin Neillands, The Battle of Normandy 1944 (2002);

- Stephen T. Powers, "Battle of Normandy: The Lingering Controversy", Journal of Military History 56 (1992):455–71.

- Russell F. Weigley, Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaign of France and Germany, 1944–45 (1981);

- Cornelius Ryan, The Longest Day', (1959);

- Stephen Ambrose, D-Day: June 6, 1944, The Battle for the Normandy Beaches, (1994);

- Milton Shulman, Defeat in the West, (New Ed edition 2003)

- Richard Holmes, The D-Day Experience: From the Invasion to the Liberation of Paris with Other and Map and CD,(2004);

- Chester Wilmot, The Struggle for Europe, (New Ed edition 1997), and

- Stephen Ashley Hart, Colossal Cracks: Montgomery's 21st Army Group in Northwest Europe, 1944–45, (2007)

- Journalists were among the foremost observers of the invasion. Two studies of their work that stand out are:

- Barney Oldfield, Never a Shot in Anger (1956); and

- Richard Collier, Fighting Words: The Correspondents of World War II (1989). CMH Pub 72–18

External links

- DDay-Overlord: a fight for freedom The Normandy campaign: history, documents, testimonies, maps

- U.S. Army's official interactive D-Day website

- The Normandy Invasion at the United States Army Center of Military History

- U.S. Navy Online Library of Selected Images: Normandy invasion

- Original Document: D-Day Statement from Dwight D. Eisenhower

- D-Day Museum Portsmouth

- BBC Archive of personal recollections of D-Day

- Justin Museum of Military History, First Hand Accounts of D-Day

- Illustrated article about Omaha Beach at 'Battlefields Europe'