Cyrillic script

| Cyrillic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Languages |

National script of: (see Languages using Cyrillic) |

Time period | Earliest variants exist c. 940 |

Parent systems | |

Sister systems |

Latin alphabet Coptic alphabet Armenian alphabet Georgian alphabet Glagolitic alphabet |

| Direction | Left-to-right |

| ISO 15924 |

Cyrl, 220Cyrs (Old Church Slavonic variant) |

Unicode alias | Cyrillic |

| |

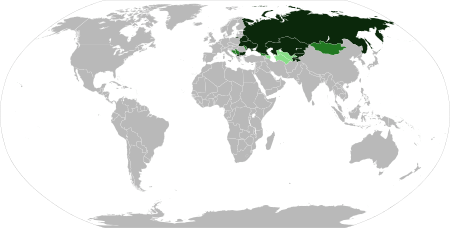

The Cyrillic script /sᵻˈrɪlɪk/ is a writing system used for various alphabets across eastern Europe and north and central Asia. It is based on the Early Cyrillic, which was developed in the First Bulgarian Empire during the 9th century AD at the Preslav Literary School.[2][3][4] It is the basis of alphabets used in various languages, past and present, in parts of southeastern Europe and northern Eurasia, especially those of Slavic origin, and non-Slavic languages influenced by Russian. As of 2011, around 252 million people in Eurasia use it as the official alphabet for their national languages, with Russia accounting for about half of them.[5] With the accession of Bulgaria to the European Union on 1 January 2007, Cyrillic became the third official script of the European Union, following the Latin script and Greek script.[6]

Cyrillic is derived from the Greek uncial script, augmented by letters from the older Glagolitic alphabet, including some ligatures. These additional letters were used for Old Church Slavonic sounds not found in Greek. The script is named in honor of the two Byzantine brothers,[7] Saints Cyril and Methodius, who created the Glagolitic alphabet earlier on. Modern scholars believe that Cyrillic was developed and formalized by early disciples of Cyril and Methodius.

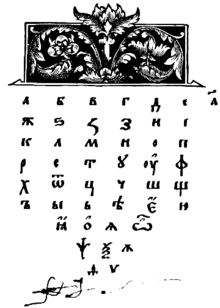

In the early 18th century the Cyrillic script used in Russia was heavily reformed by Peter the Great, who had recently returned from his Grand Embassy in western Europe. The new form of letters became closer to the Latin alphabet, several archaic letters were removed and several letters were personally designed by Peter the Great (such as Я which was inspired by Latin R). West European typography culture was also adopted.[8]

Letters

Cyrillic script spread throughout the East and South Slavic territories, being adopted for writing local languages, such as Old East Slavic. Its adaptation to local languages produced a number of Cyrillic alphabets, discussed hereafter.

| А | Б | В | Г | Д | Е | Ж | Ѕ[11] | Ꙁ | И | І | К | Л | М | Н | О | П | Р | С | Т | ОУ[12] | Ф |

| Х | Ѡ | Ц | Ч | Ш | Щ | Ъ | ЪІ[13] | Ь | Ѣ | Ꙗ | Ѥ | Ю | Ѫ | Ѭ | Ѧ | Ѩ | Ѯ | Ѱ | Ѳ | Ѵ | Ҁ[14] |

Capital and lowercase letters were not distinguished in old manuscripts.

Yeri (Ы) was originally a ligature of Yer and I (Ъ + І = Ы). Iotation was indicated by ligatures formed with the letter І: Ꙗ (not ancestor of modern Ya, Я, which is derived from Ѧ), Ѥ, Ю (ligature of І and ОУ), Ѩ, Ѭ. Sometimes different letters were used interchangeably, for example И = І = Ї, as were typographical variants like О = Ѻ. There were also commonly used ligatures like ѠТ = Ѿ.

The letters also had numeric values, based not on Cyrillic alphabetical order, but inherited from the letters' Greek ancestors.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| А | В | Г | Д | Є | Ѕ | З | И | Ѳ |

| 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 |

| І | К | Л | М | Н | Ѯ | Ѻ | П | Ч (Ҁ) |

| 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 |

| Р | С | Т | Ѵ | Ф | Х | Ѱ | Ѿ | Ц |

The early Cyrillic alphabet is difficult to represent on computers. Many of the letterforms differed from modern Cyrillic, varied a great deal in manuscripts, and changed over time. Few fonts include adequate glyphs to reproduce the alphabet. In accordance with Unicode policy, the standard does not include letterform variations or ligatures found in manuscript sources unless they can be shown to conform to the Unicode definition of a character.

The Unicode 5.1 standard, released on 4 April 2008, greatly improves computer support for the early Cyrillic and the modern Church Slavonic language. In Microsoft Windows, Segoe UI is notable for having complete support for the archaic Cyrillic letters since Windows 8.

| Letters of the Cyrillic alphabet (see also Cyrillic digraphs) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| А A |

Б Be |

В Ve |

Г Ge |

Ґ Ge upturn |

Д De |

Ђ Dje |

Ѓ Gje |

Е Ye |

Ё Yo |

Є Yest |

Ж Zhe |

| З Ze |

З́ Zje |

Ѕ Dze |

И I |

І Dotted I |

Ї Yi |

Й Short I |

Ј Je |

К Ka |

Л El |

Љ Lje |

М Em |

| Н En |

Њ Nje |

О O |

П Pe |

Р Er |

С Es |

С́ Sje |

Т Te |

Ћ Tshe |

Ќ Kje |

У U |

Ў Short U |

| Ф Ef |

Х Kha |

Ц Tse |

Ч Che |

Џ Dzhe |

Ш Sha |

Щ Shcha |

Ъ Hard sign (Yer) |

Ы Yery |

Ь Soft sign (Yeri) |

Э E |

Ю Yu |

| Я Ya |

|||||||||||

| Important Cyrillic non-Slavic letters | |||||||||||

| Ӏ Palochka |

Ә Cyrillic Schwa |

Ғ Ayn |

Ҙ Bashkir Dhe |

Ҫ Bashkir The |

Ҡ Bashkir Qa |

Җ Zhje |

Қ Ka with descender |

Ң Ng |

Ҥ En-ghe |

Ө Barred O |

Ү Straight U |

| Ұ Straight U with stroke |

Һ Shha (He) |

Ҳ Kha with descender | |||||||||

| Cyrillic letters used in the past | |||||||||||

| Ꙗ A iotified |

Ѥ E iotified |

Ѧ Yus small |

Ѫ Yus big |

Ѩ Yus small iotified |

Ѭ Yus big iotified |

Ѯ Ksi |

Ѱ Psi |

Ꙟ Yn |

Ѳ Fita |

Ѵ Izhitsa |

Ѷ Izhitsa okovy |

| Ҁ Koppa |

ОУ Uk |

Ѡ Omega |

Ѿ Ot |

Ѣ Yat |

|||||||

Letterforms and typography

The development of Cyrillic typography passed directly from the medieval stage to the late Baroque, without a Renaissance phase as in Western Europe. Late Medieval Cyrillic letters (still found on many icon inscriptions today) show a marked tendency to be very tall and narrow, with strokes often shared between adjacent letters.

Peter the Great, Czar of Russia, mandated the use of westernized letter forms in the early 18th century. Over time, these were largely adopted in the other languages that use the script. Thus, unlike the majority of modern Greek fonts that retained their own set of design principles for lower-case letters (such as the placement of serifs, the shapes of stroke ends, and stroke-thickness rules, although Greek capital letters do use Latin design principles), modern Cyrillic fonts are much the same as modern Latin fonts of the same font family. The development of some Cyrillic computer typefaces from Latin ones has also contributed to the visual Latinization of Cyrillic type.

Cyrillic uppercase and lowercase letter forms are not as differentiated as in Latin typography. Upright Cyrillic lowercase letters are essentially small capitals (with exceptions: Cyrillic ⟨а⟩, ⟨е⟩, ⟨і⟩, ⟨ј⟩, ⟨р⟩, and ⟨у⟩ adopted Western lowercase shapes, lowercase ⟨ф⟩ is typically designed under the influence of Latin ⟨p⟩, lowercase ⟨б⟩, ⟨ђ⟩ and ⟨ћ⟩ are traditional handwritten forms), although a good-quality Cyrillic typeface will still include separate small-caps glyphs.[15]

Cyrillic fonts, as well as Latin ones, have roman and italic types (practically all popular modern fonts include parallel sets of Latin and Cyrillic letters, where many glyphs, uppercase as well as lowercase, are simply shared by both). However, the native font terminology in most Slavic languages (for example, in Russian) does not use the words "roman" and "italic" in this sense.[16] Instead, the nomenclature follows German naming patterns:

- Roman type is called pryamoy shrift ("upright type")—compare with Normalschrift ("regular type") in German

- Italic type is called kursiv ("cursive") or kursivniy shrift ("cursive type")—from the German word Kursive, meaning italic typefaces and not cursive writing

- Cursive handwriting is rukopisniy shrift ("hand-written type") in Russian—in German: Kurrentschrift or Laufschrift, both meaning literally ‘running type’

As in Latin typography, a sans-serif face may have a mechanically sloped oblique type (naklonniy shrift—"sloped", or "slanted type") instead of italic.

Similarly to Latin fonts, italic and cursive types of many Cyrillic letters (typically lowercase; uppercase only for hand-written or stylish types) are very different from their upright roman types. In certain cases, the correspondence between uppercase and lowercase glyphs does not coincide in Latin and Cyrillic fonts: for example, italic Cyrillic ⟨т⟩ is the lowercase counterpart of ⟨Т⟩ not of ⟨М⟩.

A boldfaced type is called poluzhirniy shrift ("semi-bold type"), because there existed fully boldfaced shapes that have been out of use since the beginning of the 20th century.

A bold italic combination (bold slanted) does not exist for all font families.

In Standard Serbian, as well as in Macedonian,[17] some italic and cursive letters are different from those used in other languages. These letter shapes are often used in upright fonts as well, especially for advertisements, road signs, inscriptions, posters and the like, less so in newspapers or books. The Cyrillic lowercase ⟨б⟩ has a slightly different design both in the roman and italic types, which is similar to the lowercase Greek letter delta, ⟨δ⟩.

The following table shows the differences between the upright and italic Cyrillic letters of the Russian alphabet. Italic forms significantly different from their upright analogues, or especially confusing to users of a Latin alphabet, are highlighted.

| а | б | в | г | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

| а | б | в | г | д | е | ё | ж | з | и | й | к | л | м | н | о | п | р | с | т | у | ф | х | ц | ч | ш | щ | ъ | ы | ь | э | ю | я |

Note: in some fonts or styles, lowercase italic Cyrillic ⟨д⟩ (⟨д⟩) may look like Latin ⟨g⟩ and lowercase italic Cyrillic ⟨т⟩ (⟨т⟩) may look exactly like a capital italic ⟨T⟩ (⟨T⟩), only small.

Cyrillic alphabets

Among others, Cyrillic is the standard script for writing the following languages:

- Slavic languages: Belarusian, Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, Rusyn, Serbo-Croatian (for Standard Serbian, Bosnian, and Montenegrin), Ukrainian

- Non-Slavic languages: Abkhaz, Aleut (now mostly in church texts), Bashkir, Chuvash, Erzya, Kazakh, Kildin Sami, Komi, Kyrgyz, Mari, Moksha, Mongolian, Ossetic, Romani (some dialects), Sakha/Yakut, Tajik, Tatar, Tlingit (now only in church texts), Tuvan, Udmurt, Yuit (Siberian Yupik), and Yupik (in Alaska).

The Cyrillic script has also been used for languages of Alaska,[18] Slavic Europe (except for Western Slavic and some Southern Slavic), the Caucasus, Siberia, and the Russian Far East.

The first alphabet derived from Cyrillic was Abur, used for the Komi language. Other Cyrillic alphabets include the Molodtsov alphabet for the Komi language and various alphabets for Caucasian languages.

Name

Because the script was conceived and popularised by the followers of Cyril and Methodius, rather than by Cyril and Methodius themselves, its name denotes homage rather than authorship. The name "Cyrillic" often confuses people who are not familiar with the script's history, because it does not identify a country of origin (in contrast to the "Greek alphabet"). Some call it the "Russian alphabet" because Russian is the most popular and influential alphabet based on the script. Some Bulgarian intellectuals, notably Stefan Tsanev, have expressed concern over this, and have suggested that the Cyrillic script be called the "Bulgarian alphabet" instead, for the sake of historical accuracy.[19]

In Bulgarian, Macedonian, Russian, and Serbian, the Cyrillic script is also known as azbuka, derived from the old names of the first two letters of most Cyrillic alphabets (just as the term alphabet came from the first two Greek letters alpha and beta).

History

The Cyrillic script was created in the First Bulgarian Empire[20] and is derived from the Greek uncial script letters, augmented by ligatures and consonants from the older Glagolitic alphabet for sounds not found in Greek. Tradition holds that Cyrillic and Glagolitic were formalized either by Saints Cyril and Methodius who brought Christianity to the southern Slavs, or by their disciples.[21][22][23][24] Paul Cubberley posits that although Cyril may have codified and expanded Glagolitic, it was his students in the First Bulgarian Empire under Tsar Simeon the Great that developed Cyrillic from the Greek letters in the 890s as a more suitable script for church books.[20] Later Cyrillic spread among other Slavic peoples, as well as among non-Slavic Vlachs and Moldavians.

Cyrillic and Glagolitic were used for the Church Slavonic language, especially the Old Church Slavonic variant. Hence expressions such as "И is the tenth Cyrillic letter" typically refer to the order of the Church Slavonic alphabet; not every Cyrillic alphabet uses every letter available in the script.

|

Egyptian hieroglyphs 32 c. BCE

|

The Cyrillic script came to dominate Glagolitic in the 12th century. The literature produced in the Old Bulgarian language soon spread north and became the lingua franca of the Balkans and Eastern Europe, where it came to also be known as Old Church Slavonic.[25][26][27][28][29] The alphabet used for the modern Church Slavonic language in Eastern Orthodox and Eastern Catholic rites still resembles early Cyrillic. However, over the course of the following millennium, Cyrillic adapted to changes in spoken language, developed regional variations to suit the features of national languages, and was subjected to academic reform and political decrees. A notable example of such linguistic reform can be attributed to Vuk Stefanović Karadžić who updated the Serbian Cyrillic alphabet by removing certain graphemes no longer represented in the vernacular, and introducing graphemes specific to Serbian (i.e. Љ Њ Ђ Ћ Џ Ј), distancing it from Church Slavonic alphabet in use prior to the reform. Today, many languages in the Balkans, Eastern Europe, and northern Eurasia are written in Cyrillic alphabets.

Relationship to other writing systems

Latin script

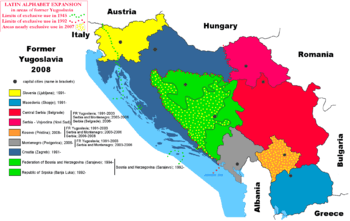

A number of languages written in a Cyrillic alphabet have also been written in a Latin alphabet, such as Azerbaijani, Uzbek, Serbian and Romanian (in the Republic of Moldova until 1989, in Romania throughout the 19th century). After the disintegration of the Soviet Union in 1991, some of the former republics officially shifted from Cyrillic to Latin. The transition is complete in most of Moldova (except the breakaway region of Transnistria, where Moldovan Cyrillic is official), Turkmenistan, and Azerbaijan, but Uzbekistan still uses both systems. The Russian government has mandated that Cyrillic must be used for all public communications in all federal subjects of Russia, to promote closer ties across the federation. This act was controversial for speakers of many Slavic languages; for others, such as Chechen and Ingush speakers, the law had political ramifications. For example, the separatist Chechen government mandated a Latin script which is still used by many Chechens. Those in the diaspora especially refuse to use the Chechen Cyrillic alphabet, which they associate with Russian imperialism.

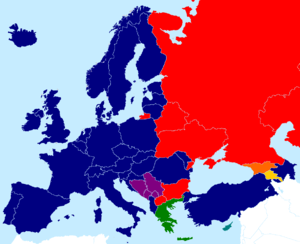

Alphabets in Europe

Greek

Greek & Latin

Latin

Latin and Cyrillic

Cyrillic

Georgian

Armenian

|

Standard Serbian uses both the Cyrillic and Latin scripts. Cyrillic is nominally the official script of Serbia's administration according to the Serbian constitution;[30] however, the law does not regulate scripts in standard language, or standard language itself by any means. In practice the scripts are equal, with Latin being used more often in a less official capacity.[31]

The Zhuang alphabet, used between the 1950s and 1980s in portions of the People's Republic of China, used a mixture of Latin, phonetic, numeral-based, and Cyrillic letters. The non-Latin letters, including Cyrillic, were removed from the alphabet in 1982 and replaced with Latin letters that closely resembled the letters they replaced.

Romanization

There are various systems for Romanization of Cyrillic text, including transliteration to convey Cyrillic spelling in Latin letters, and transcription to convey pronunciation.

Standard Cyrillic-to-Latin transliteration systems include:

- Scientific transliteration, used in linguistics, is based on the Serbo-Croatian Latin alphabet.

- The Working Group on Romanization Systems[32] of the United Nations recommends different systems for specific languages. These are the most commonly used around the world.

- ISO 9:1995, from the International Organization for Standardization.

- American Library Association and Library of Congress Romanization tables for Slavic alphabets (ALA-LC Romanization), used in North American libraries.

- BGN/PCGN Romanization (1947), United States Board on Geographic Names & Permanent Committee on Geographical Names for British Official Use).

- GOST 16876, a now defunct Soviet transliteration standard. Replaced by GOST 7.79, which is ISO 9 equivalent.

- Volapuk encoding, an informal rendering of Cyrillic text over Latin-alphabet ASCII.

See also Romanization of Belarusian, Bulgarian, Kyrgyz, Russian, Macedonian and Ukrainian.

Cyrillization

Representing other writing systems with Cyrillic letters is called Cyrillization.

Computer encoding

Unicode

As of Unicode version 9.0, Cyrillic letters, including national and historical alphabets, are encoded across several blocks:

- Cyrillic: U+0400–U+04FF

- Cyrillic Supplement: U+0500–U+052F

- Cyrillic Extended-A: U+2DE0–U+2DFF

- Cyrillic Extended-B: U+A640–U+A69F

- Cyrillic Extended-C: U+1C80–U+1C8F

- Phonetic Extensions: U+1D2B, U+1D78

- Combining Half Marks: U+FE2E–U+FE2F

The characters in the range U+0400 to U+045F are basically the characters from ISO 8859-5 moved upward by 864 positions. The characters in the range U+0460 to U+0489 are historic letters, not used now. The characters in the range U+048A to U+052F are additional letters for various languages that are written with Cyrillic script.

Unicode as a general rule does not include accented Cyrillic letters. A few exceptions are:

- combinations that are considered as separate letters of respective alphabets, like Й, Ў, Ё, Ї, Ѓ, Ќ (as well as many letters of non-Slavic alphabets);

- two most frequent combinations orthographically required to distinguish homonyms in Bulgarian and Macedonian: Ѐ, Ѝ;

- a few Old and New Church Slavonic combinations: Ѷ, Ѿ, Ѽ.

To indicate stressed or long vowels, combining diacritical marks can be used after the respective letter (for example, U+0301 ◌́ COMBINING ACUTE ACCENT: ы́ э́ ю́ я́ etc.).

Some languages, including Church Slavonic, are still not fully supported.

Unicode 5.1, released on 4 April 2008, introduces major changes to the Cyrillic blocks. Revisions to the existing Cyrillic blocks, and the addition of Cyrillic Extended A (2DE0...2DFF) and Cyrillic Extended B (A640...A69F), significantly improve support for the early Cyrillic alphabet, Abkhaz, Aleut, Chuvash, Kurdish, and Mordvin.[33]

Other

Punctuation for Cyrillic text is similar to that used in European Latin-alphabet languages.

Other character encoding systems for Cyrillic:

- CP866 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in MS-DOS also known as GOST-alternative. Cyrillic characters go in their native order, with a "window" for pseudographic characters.

- ISO/IEC 8859-5 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by International Organization for Standardization

- KOI8-R – 8-bit native Russian character encoding. Invented in the USSR for use on Soviet clones of American IBM and DEC computers. The Cyrillic characters go in the order of their Latin counterparts, which allowed the text to remain readable after transmission via a 7-bit line that removed the most significant bit from each byte—the result became a very rough, but readable, Latin transliteration of Cyrillic. Standard encoding of early 1990s for Unix systems and the first Russian Internet encoding.

- KOI8-U – KOI8-R with addition of Ukrainian letters.

- MIK – 8-bit native Bulgarian character encoding for use in Microsoft DOS.

- Windows-1251 – 8-bit Cyrillic character encoding established by Microsoft for use in Microsoft Windows. The simplest 8-bit Cyrillic encoding—32 capital chars in native order at 0xc0–0xdf, 32 usual chars at 0xe0–0xff, with rarely used "YO" characters somewhere else. No pseudographics. Former standard encoding in some GNU/Linux distributions for Belarusian and Bulgarian, but currently displaced by UTF-8.

- GOST-main.

- GB 2312 – Principally simplified Chinese encodings, but there are also the basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

- JIS and Shift JIS – Principally Japanese encodings, but there are also the basic 33 Russian Cyrillic letters (in upper- and lower-case).

Keyboard layouts

Each language has its own standard keyboard layout, adopted from typewriters. With the flexibility of computer input methods, there are also transliterating or phonetic/homophonic keyboard layouts made for typists who are more familiar with other layouts, like the common English qwerty keyboard. When practical Cyrillic keyboard layouts or fonts are not available, computer users sometimes use transliteration or look-alike "volapuk" encoding to type languages that are normally written with the Cyrillic alphabet.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cyrillic script. |

- .бг

- .қаз

- .рф

- .срб

- .укр

- Appendix of Cyrillic alphabets

- Cyrillic (Unicode block)

- Cyrillic Alphabet Day

- Cyrillic digraphs

- Faux Cyrillic, real or fake Cyrillic letters used to give Latin-alphabet text a Soviet or Russian feel

- Languages using Cyrillic

- List of Cyrillic digraphs

- List of Cyrillic letters

- Russian cursive

- Russian manual alphabet

- Yugoslav manual alphabet

- Russian braille

- Yugoslav braille

- Vladislav the Grammarian

Notes

- ↑ Oldest alphabet found in Egypt. BBC. 1999-11-15. Retrieved 2015-01-14.

- ↑ Dvornik, Francis (1956). The Slavs: Their Early History and Civilization. Boston: American Academy of Arts and Sciences. p. 179.

The Psalter and the Book of Prophets were adapted or "modernized" with special regard to their use in Bulgarian churches, and it was in this school that glagolitic writing was replaced by the so-called Cyrillic writing, which was more akin to the Greek uncial, simplified matters considerably and is still used by the Orthodox Slavs.

- ↑ Florin Curta (2006). Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500–1250. Cambridge Medieval Textbooks. Cambridge University Press. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0521815398.

- ↑ J. M. Hussey, Andrew Louth (2010). "The Orthodox Church in the Byzantine Empire". Oxford History of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. p. 100. ISBN 0191614882.

- ↑ List of countries by population

- ↑ Leonard Orban (24 May 2007). "Cyrillic, the third official alphabet of the EU, was created by a truly multilingual European" (PDF). europe.eu. Retrieved 3 August 2014.

- ↑ Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05, s.v. "Cyril and Methodius, Saints"; Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Incorporated, Warren E. Preece – 1972, p. 846, s.v., "Cyril and Methodius, Saints" and "Eastern Orthodoxy, Missions ancient and modern"; Encyclopedia of World Cultures, David H. Levinson, 1991, p. 239, s.v., "Social Science"; Eric M. Meyers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, p. 151, 1997; Lunt, Slavic Review, June 1964, p. 216; Roman Jakobson, Crucial problems of Cyrillo-Methodian Studies; Leonid Ivan Strakhovsky, A Handbook of Slavic Studies, p. 98; V. Bogdanovich, History of the ancient Serbian literature, Belgrade, 1980, p. 119

- ↑ "Civil Type and Kis Cyrillic". typejournal.ru. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ А. Н. Стеценко. Хрестоматия по Старославянскому Языку, 1984.

- ↑ Cubberley, Paul. The Slavic Alphabets, 1996.

- ↑ Variant form Ꙃ

- ↑ Variant form Ꙋ

- ↑ Variant form ЪИ

- ↑ Lunt, Horace G. Old Church Slavonic Grammar, Seventh Edition, 2001.

- ↑ Bringhurst (2002) writes "in Cyrillic, the difference between normal lower case and small caps is more subtle than it is in the Latin or Greek alphabets,..." (p 32) and "in most Cyrillic faces, the lower case is close in color and shape to Latin small caps" (p 107).

- ↑ Name ital'yanskiy shrift (Italian font) in Russian refers to a particular font family JPG, whereas rimskiy shrift (roman font) is just a synonym for Latin font, Latin alphabet.

- ↑ Serbian Cyrillic Letters BE, GHE, DE, PE, TE, Janko Stamenovic (collection of selected commented answers received in Unicode mailing list ([email protected]) between 29.12.1999 and 17.01.2000).

- ↑ "Orthodox Language Texts", Retrieved 2011-06-20

- ↑ Tsanev, Stefan. Български хроники, том 4 (Bulgarian Chronicles, Volume 4), Sofia, 2009, p. 165

- 1 2 Paul Cubberley (1996) "The Slavic Alphabets". In Daniels and Bright, eds. The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-507993-0.

- ↑ Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05, s.v. "Cyril and Methodius, Saints"; Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica Incorporated, Warren E. Preece – 1972, p.846, s.v., "Cyril and Methodius, Saints" and "Eastern Orthodoxy, Missions ancient and modern"; Encyclopedia of World Cultures, David H. Levinson, 1991, p.239, s.v., "Social Science"; Eric M. Meyers, The Oxford Encyclopedia of Archaeology in the Near East, p.151, 1997; Lunt, Slavic Review, June, 1964, p. 216; Roman Jakobson, Crucial problems of Cyrillo-Methodian Studies; Leonid Ivan Strakhovsky, A Handbook of Slavic Studies, p.98; V. Bogdanovich, History of the ancient Serbian literature, Belgrade, 1980, p.119

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopaedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–05, O.Ed. Saints Cyril and Methodius "Cyril and Methodius, Saints) 869 and 884, respectively, “Greek missionaries, brothers, called Apostles to the Slavs and fathers of Slavonic literature."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, Major alphabets of the world, Cyrillic and Glagolitic alphabets, 2008, O.Ed. "The two early Slavic alphabets, the Cyrillic and the Glagolitic, were invented by St. Cyril, or Constantine (c. 827–869), and St. Methodii (c. 825–884). These men from Thessaloniki who became apostles to the southern Slavs, whom they converted to Christianity."

- ↑ Kazhdan, Alexander P. (1991). The Oxford dictionary of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 507. ISBN 0-19-504652-8.

Constantine (Cyril) and his brother Methodius were the sons of the droungarios Leo and Maria, who may have been a Slav.

- ↑ "On the relationship of old Church Slavonic to the written language of early Rus'" Horace G. Lunt; Russian Linguistics, Volume 11, Numbers 2–3 / January, 1987

- ↑ Schenker, Alexander (1995). The Dawn of Slavic. Yale University Press. pp. 185–186, 189–190.

- ↑ Lunt, Horace. Old Church Slavonic Grammar. Mouton de Gruyter. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Wien, Lysaght (1983). Old Church Slavonic (Old Bulgarian)-Middle Greek-Modern English dictionary. Verlag Bruder Hollinek.

- ↑ Benjamin W. Fortson. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction, p. 374

- ↑ Serbian constitution

- ↑ http://www.csmonitor.com/World/Europe/2008/0529/p20s01-woeu.html

- ↑ UNGEGN Working Group on Romanization Systems

- ↑ "IOS Universal Multiple-Octet Coded Character Set" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-06-13.

References

- Ivan G. Iliev. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet. Plovdiv. 2012. Short History of the Cyrillic Alphabet

- Bringhurst, Robert (2002). The Elements of Typographic Style (version 2.5), pp. 262–264. Vancouver, Hartley & Marks. ISBN 0-88179-133-4.

- Nezirović, M. (1992). Jevrejsko-španjolska književnost. Sarajevo: Svjetlost. [cited in Šmid, 2002]

- Šmid, Katja (2002). ""Los problemas del estudio de la lengua sefardí" (PDF). (603 KiB)", in Verba Hispanica, vol X. Liubliana: Facultad de Filosofía y Letras de la Universidad de Liubliana. ISSN 0353-9660.

- 'The Lives of St. Tsurho and St. Strahota', Bohemia, 1495, Vatican Library

- Philipp Ammon: Tractatus slavonicus. in: Sjani (Thoughts) Georgian Scientific Journal of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature, N 17, 2016, pp. 248-56

External links

- The Cyrillic Charset Soup overview and history of Cyrillic charsets.

- Transliteration of Non-Roman Scripts, a collection of writing systems and transliteration tables

- History and development of the Cyrillic alphabet

- data entry in Old Cyrillic / Стара Кирилица

- Cyrillic and it's Long Journey East - NamepediA Blog, article about the Cyrillic script

- Vladimir M. Alpatov (24 January 2013). "Latin Alphabet for the Russian Language". Soundcloud (Podcast). The University of Edinburgh. Retrieved 28 January 2016.