Criticism of religion

| Part of a series on |

| Irreligion |

|---|

|

People

|

|

Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Criticism of religion |

|---|

| By religion |

| By religious figure |

| By text |

| Religious violence |

| Related topics |

Criticism of religion is criticism of the concepts, doctrines, validity, and/or practices of religion, including associated political and social implications.[1]

Criticism of religion has a long history. In ancient Greece, it goes back at least to the 5th century BCE with Diagoras "the Atheist" of Melos; in ancient Rome, an early known example is Lucretius' De Rerum Natura from the 1st century BCE. Criticism of religion is complicated by the fact that there exist multiple definitions and concepts of religion in different cultures and languages. With the existence of diverse categories of religion such as monotheism, polytheism, pantheism, nontheism and diverse specific religions such as Christianity, Judaism, Islam, Taoism, Buddhism, and many others; it is not always clear to whom the criticisms are aimed at or to what extent they are applicable to other religions.

Every exclusive religion on Earth that promotes exclusive truth claims necessarily denigrates the truth claims of other religions.[2] Critics of religion in general often regard religion as outdated, harmful to the individual, harmful to society, an impediment to the progress of science, a source of immoral acts or customs, and a political tool for social control.

History of the Concept of "Religion"

Religion (from O.Fr. religion "religious community", from L. religionem (nom. religio) "respect for what is sacred, reverence for the gods",[3] "obligation, the bond between man and the gods"[4]) is derived from the Latin religiō.

In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root religio which is the source of the modern word "religion", was understood as an individual virtue of worship and never referring to doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.[5] The modern concept of "religion" as an abstraction which entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines, is a recent invention in the English language since such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and globalization in the age of exploration.[5] During this time period, contact with numerous foreign and indigenous cultures with non-European languages, that did not have equivalent concepts or words for religion, became more common.[5] It was in the 17th century that the concept of "religion" received its modern shape despite the fact that ancient texts like the Bible, the Quran, and other ancient sacred texts did not have a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[6] For example, the Greek word threskeia, which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus and is found in texts like the New Testament, is sometimes translated as "religion" today, however, the term was understood as "worship" in a generic sense well into the medieval period.[6] In the Quran, the Arabic word din is often translated as "religion" in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed din as "law".[6] Even in the 1st century AD, Josephus had used the Greek term ioudaismos, which some translate as "Judaism" today, even though he used it as an ethnic term, not one linked to modern abstract concepts of religion as a set of beliefs.[6] It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.[5][7] Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of "religion" since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this Western idea.[7]

According to the philologist Max Müller in the 19th century, the root of the English word "religion", the Latin religio, was originally used to mean only "reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety" (which Cicero further derived to mean "diligence").[8][9] Max Müller characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called "law".[10]

Many languages have words that can be translated as "religion", but they may use them in a very different way, and some have no word for religion at all. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as "religion", also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of power.[11][12]

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[13] One of its central concepts is "halakha", meaning the "walk" or "path" sometimes translated as "law", which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.[14]

History of the Criticism of Religion

The 1st century BCE Roman poet, Titus Lucretius Carus, in his work De Rerum Natura, wrote: "But 'tis that same religion oftener far / Hath bred the foul impieties of men:"[15] A philosopher of the Epicurean school, Lucretius believed the world was composed solely of matter and void, and that all phenomena could be understood as resulting from purely natural causes. Lucretius, like Epicurus, felt that religion was born of fear and ignorance, and that understanding the natural world would free people of its shackles;[16] however, he did believe in gods.[17] He was not against religion in and of itself, but against traditional religion which he saw as superstition for teaching that gods interfered with the world.[18]

Niccolò Machiavelli, at the beginning of the 16th century said: "We Italians are irreligious and corrupt above others... because the church and her representatives have set us the worst example."[19] To Machiavelli, religion was merely a tool, useful for a ruler wishing to manipulate public opinion.[20]

In the 18th century Voltaire was a deist and was strongly critical of religious intolerance. Voltaire complained about Jews killed by other Jews for worshiping a golden calf and similar actions, he also condemned how Christians killed other Christians over religious differences and how Christians killed Native Americans for not being baptised. Voltaire claimed the real reason for these killings was that Christians wanted to plunder the wealth of those killed. Voltaire was also critical of Muslim intolerance.[21]

Also in the 18th century David Hume criticised teleological arguments for religion. Hume claimed that natural explanations for the order in the universe were reasonable, see Design argument. Demonstrating the unsoundness of the philosophical basis for religion was an important aim of Hume's writings.[22]

In the early 21st century the New Atheists, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins and Christopher Hitchens, were prominent as critics of religion.[23][24]

Criticism of religious concepts

Some criticisms on monotheistic religions have been:

- Sometimes conflict with science. (i.e. Genesis creation myth)[26]

- Revelations may conflict internally (i.e. discrepancies in the Bible among the four Gospels of the New Testament).[27][28][29]

Conflicting claims of "one true faith"

In the context of theistic belief, Stephen Roberts[30] said "I contend we are both atheists, I just believe in one fewer god than you do. When you understand why you dismiss all the other possible gods, you will understand why I dismiss yours."[31]

Explanations as non-divine in origin

Social construct

Dennett and Harris have asserted that theist religions and their scriptures are not divinely inspired, but man made to fulfill social, biological, and political needs.[32][33] Dawkins balances the benefits of religious beliefs (mental solace, community-building, promotion of virtuous behavior) against the drawbacks.[34] Such criticisms treat religion as a social construct[35] and thus just another human ideology.

Narratives to provide comfort and meaning

Daniel Dennett has argued that, with the exception of more modern religions such as Raëlism, Mormonism, Scientology, and the Bahá'í Faith, most religions were formulated at a time when the origin of life, the workings of the body, and the nature of the stars and planets were poorly understood.[36]

These narratives were intended to give solace and a sense of relationship with larger forces. As such, they may have served several important functions in ancient societies. Examples include the views many religions traditionally had towards solar and lunar eclipses, and the appearance of comets (forms of astrology).[37][38] Given current understanding of the physical world, where human knowledge has increased dramatically; Dawkins, and French atheist philosopher Michel Onfray contend that continuing to hold on to these belief systems is irrational and no longer useful.[34][39]

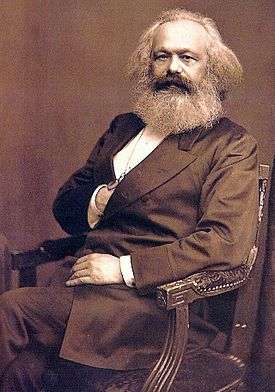

Opium of the people

Religious suffering is, at the same time, the expression of real suffering and a protest against real suffering. Religion is the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions. It is the opium of the people.

According to Karl Marx, the father of "scientific socialism", religion is a tool used by the ruling classes whereby the masses can shortly relieve their suffering via the act of experiencing religious emotions. It is in the interest of the ruling classes to instill in the masses the religious conviction that their current suffering will lead to eventual happiness. Therefore, as long as the public believes in religion, they will not attempt to make any genuine effort to understand and overcome the real source of their suffering, which in Marx's opinion was their capitalist economic system. In this perspective, Marx saw religion as escapism.[40]

Marx also viewed the Christian doctrine of original sin as being deeply anti-social in character. Original sin, he argued, convinces people that the source of their misery lies in the inherent and unchangeable "sinfulness" of humanity rather than in the forms of social organization and institutions, which, Marx argued, can be changed through the application of collective social planning.[41]

Viruses of the mind

In his 1976 book The Selfish Gene, Richard Dawkins coined the term memes to describe informational units that can be transmitted culturally, analogous to genes.[42] He later used this concept in the essay "Viruses of the Mind" to explain the persistence of religious ideas in human culture.[43]

John Bowker criticized the idea that "God" and "Faith" are viruses of the mind, suggesting that Dawkins' "account of religious motivation ... is ... far removed from evidence and data" and that, even if the God-meme approach were valid, "it does not give rise to one set of consequences ... Out of the many behaviours it produces, why are we required to isolate only those that might be regarded as diseased?"[44] Alister McGrath has responded by arguing that "memes have no place in serious scientific reflection",[45] that there is strong evidence that such ideas are not spread by random processes, but by deliberate intentional actions,[46] that "evolution" of ideas is more Lamarckian than Darwinian,[47] and that there is no evidence (and certainly none in the essay) that epidemiological models usefully explain the spread of religious ideas.[48] McGrath also cites a metareview of 100 studies and argues that "if religion is reported as having a positive effect on human well-being by 79% of recent studies in the field, then it cannot be conceivably regarded as analogous to a virus?"[49]

Mental illness or delusion

Others, such as Sam Harris, compare religion to mental illness, saying it "allows otherwise normal human beings to reap the fruits of madness and consider them holy."[50]

There are also psychological studies into the phenomenon of mysticism, and the links between disturbing aspects of certain mystic's experiences and their links to childhood abuse.[51][52][53] In another line of research, Clifford A. Pickover explores evidence suggesting that temporal lobe epilepsy may be linked to a variety of spiritual or ‘other worldly’ experiences, such as spiritual possession, originating from altered electrical activity in the brain.[54] Carl Sagan, in his last book The Demon-Haunted World: Science as a Candle in the Dark, presented his case for the miraculous sightings of religious figures in the past and the modern sightings of UFOs coming from the same mental disorder. According to Vilayanur S. Ramachandran, "It's possible that many great religious leaders had temporal lobe seizures and this predisposes them to having visions, having mystical experiences."[55] Michael Persinger stimulated the temporal lobes of the brain artificially with a magnetic field using a device nicknamed the "God helmet," and was able to artificially induce religious experiences along with near-death experiences and ghost sightings.[56] John Bradshaw has stated, "Some forms of temporal lobe tumours or epilepsy are associated with extreme religiosity. Recent brain imaging of devotees engaging in prayer or transcendental meditation has more precisely identified activation in such sites — God-spots, as Vilayanur Ramachandran calls them. Psilocybin from mushrooms contacts the serotonergic system, with terminals in these and other brain regions, generating a sense of cosmic unity, transcendental meaning and religious ecstasy. Certain physical rituals can generate both these feelings and corresponding serotonergic activity."[57]

Keith Ward in his book Is Religion Dangerous? addresses the claim that religious belief is a delusion. He quotes the definition in the Oxford Companion to Mind as "a fixed, idiosyncratic belief, unusual in the culture to which the person belongs," and notes that "[n]ot all false opinions are delusions." Ward then characterizes a delusion as a "clearly false opinion, especially as a symptom of a mental illness," an "irrational belief" that is "so obviously false that all reasonable people would see it as mistaken." He then says that belief in God is different, since "[m]ost great philosophers have believed in God, and they are rational people". He argues that "[a]ll that is needed to refute the claim that religious belief is a delusion is one clear example of someone who exhibits a high degree of rational ability, who functions well in the ordinary affairs of life ... and who can produce a reasonable and coherent defense of their beliefs" and claims that there are many such people, "including some of the most able philosophers and scientists in the world today."[58]

Immature stage of societal development

Philosopher Auguste Comte posited that many societal constructs pass through three stages, and that religion corresponds to the two earlier, or more primitive stages by stating: "From the study of the development of human intelligence, in all directions, and through all times, the discovery arises of a great fundamental law, to which it is necessarily subject, and which has a solid foundation of proof, both in the facts of our organization and in our historical experience. The law is this: that each of our leading conceptions – each branch of our knowledge – passes successively through three different theoretical conditions: the theological, or fictitious; the metaphysical, or abstract; and the scientific, or positive." [59]

Harm to individuals

Some have criticized the effects of adherence to dangerous practices such as self-sacrifice.[60]

Inadequate medical care

A detailed study in 1998 found 140 instances of deaths of children due to religion-based medical neglect. Most of these cases involved religious parents relying on prayer to cure the child's disease, and withholding medical care.[61]

Jerusalem syndrome

Jerusalem has lent its name to a unique psychological phenomenon where Jewish or Christian individuals who develop obsessive religious themed ideas or delusions (sometimes believing themselves to be Jesus Christ or another prophet) will feel compelled to travel to Jerusalem.[62][63]

During a period of 13 years (1980–1993) for which admissions to the Kfar Shaul Mental Health Centre in Jerusalem were analyzed, it was reported[64] that 1,200 tourists with severe, Jerusalem-themed mental problems, were referred to this clinic. Of these, 470 were admitted to hospital. On average, 100 such tourists have been seen annually, 40 of them requiring admission to hospital. About 2 million tourists visit Jerusalem each year. Kalian and Witztum note that as a proportion of the total numbers of tourists visiting the city, this is not significantly different from any other city.[65][66] The statements of these claims has however been disputed, with the arguments that experiencers of the Jerusalem syndrome already were mentally ill.[65][67]

Honor killings and stoning

Still occurring in some parts of the world, an honor killing is when a person is killed by family for bringing dishonor or shame upon the family.[68] While religions such as Islam are often blamed for such acts, Tahira Shaid Khan, a professor of women's issues at Aga Khan University, notes that there is nothing in the Qur'an that permits or sanctions honor killings.[69] Khan instead blames it on attitudes (across different classes, ethnic and religious groups) that view women as property with no rights of their own as the motivation for honor killings.[69] Khan also argues that this view results in violence against women and their being turned "into a commodity which can be exchanged, bought and sold".[70]

Stoning is a form of capital punishment whereby a group throws stones at a person until death ensues. As of September 2010, stoning is a punishment that is included in the laws in some countries including Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, the United Arab Emirates, and some states in Nigeria[71] as punishment for zina al-mohsena ("adultery of married persons").[72] While stoning may not be codified in the laws of Afghanistan and Somalia, both countries have seen several incidents of stoning to death.[73][74]

Until the early 2000s, stoning was a legal form of capital punishment in Iran. In 2002, the Iranian judiciary officially placed a moratorium on stoning.[75] In 2005, judiciary spokesman Jamal Karimirad stated, "in the Islamic republic, we do not see such punishments being carried out", further adding that if stoning sentences were passed by lower courts, they were overruled by higher courts and "no such verdicts have been carried out."[76] In 2008, the judiciary decided to fully scrap the punishment from the books in legislation submitted to parliament for approval.[77] In early 2013, Iranian parliament published official report about excluding stoning from penal code and it accused Western media for spreading "noisy propaganda" about the case.[78]

Genital modification and mutilation

According to the World Health Organization, female genital mutilation has no health benefits, is a violation of human rights, and though no religious texts prescribe the practice, some practitioners do believe there is support for it. WHO also notes that in terms of religious leaders, "some promote it, some consider it irrelevant to religion, and others contribute to its elimination" and the influences for its continuation come from many sources: "Local structures of power and authority, such as community leaders, religious leaders, circumcisers, and even some medical personnel can contribute to upholding the practice.".[79]

Counterarguments to religion as harmful to individuals

There is substantial research suggesting that religious people are happier and less stressed.[80][81] Surveys by Gallup, the National Opinion Research Center and the Pew Organization conclude that spiritually committed people are twice as likely to report being "very happy" than the least religiously committed people.[82] An analysis of over 200 social studies contends that "high religiousness predicts a rather lower risk of depression and drug abuse and fewer suicide attempts, and more reports of satisfaction with sex life and a sense of well-being,"[83] and a review of 498 studies published in peer-reviewed journals concluded that a large majority of them showed a positive correlation between religious commitment and higher levels of perceived well-being and self-esteem and lower levels of hypertension, depression, and clinical delinquency.[84][85] Surveys suggest a strong link between faith and altruism.[86] Studies by Keith Ward show that overall religion is a positive contributor to mental health,[87] and a meta-analysis of 34 recent studies published between 1990 and 2001 also found that religiosity has a salutary relationship with psychological adjustment, being related to less psychological distress, more life satisfaction, and better self-actualization.[88] Andrew E. Clark and Orsolya Lelkes surveyed 90,000 people in 26 European countries and found that "[one's own] religious behaviour is positively correlated with individual life satisfaction.", greater overall "religiosity" in a region also correlates positively with "individual life satisfaction". The reverse was found to be true: a large "atheist" (non-religious) population "has negative spillover effects" for both the religious and non-religious members of the population.[89] Finally, a recent systematic review of 850 research papers on the topic concluded that "the majority of well-conducted studies found that higher levels of religious involvement are positively associated with indicators of psychological well-being (life satisfaction, happiness, positive affect, and higher morale) and with less depression, suicidal thoughts and behavior, drug/alcohol use/abuse."[90]

However, as of 2001, most of those studies were conducted within the United States.[91] There is no significant correlation between religiosity and individual happiness in Denmark and the Netherlands, countries that have lower rates of religion than the United States.[92] A cross-national investigation on subjective well-being has noted that, globally, religious people are usually happier than nonreligious people, though nonreligious people can also reach high levels of happiness.[93] The 2013 World Happiness Report mentions that once crude factors are taken into account, there are no differences in life satisfaction between religious and less religious countries, even though a meta analysis concludes that greater religiosity is mildly associated with fewer depressive symptoms and 75% of studies find at least some positive effect of religion on well-being.[94]

Harm to society

Some aspects of religion are criticized on the basis that they damage society as a whole. Steven Weinberg, for example, states it takes religion to make good people do evil.[95] Bertrand Russell and Richard Dawkins cite religiously inspired or justified violence, resistance to social change, attacks on science, repression of women, and homophobia.[96]

Hartung has claimed that major religious moral codes can lead to "us vs. them" group solidarity and mentality which can dehumanise or demonise individuals outside their group as "not fully human", or less worthy. Results can vary from mild discrimination to outright genocide.[97] A poll by The Guardian, a UK newspaper noted that 82% of the British people believe that religion is socially divisive and that this effect is harmful despite the observation that non-believers outnumber believers 2 to 1.[98]

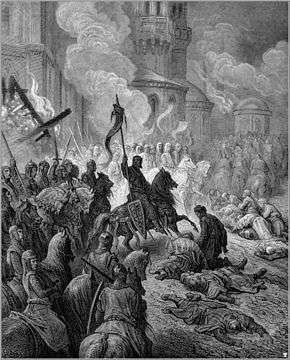

Holy war and religious terrorism

Although the causes of terrorism are complex, it may be that terrorists are partially reassured by their religious views that God is on their side and will reward them in heaven for punishing unbelievers.[99][100]

These conflicts are among the most difficult to resolve, particularly where both sides believe that God is on their side and has endorsed the moral righteousness of their claims.[99] One of the most infamous quotes associated with religious fanaticism was made in 1209 during the siege of Béziers, a Crusader asked the Papal Legate Arnaud Amalric how to tell Catholics from Cathars when the city was taken, to which Amalric replied: "Tuez-les tous; Dieu reconnaitra les siens," or "Kill them all; God will recognize his own."[101]

Theoretical physicist Michio Kaku considers religious terrorism as one of the main threats in humanity's evolution from a Type 0 to Type 1 civilization.[102]

Arguments against religion being a significant cause of violence

Some argue that religious violence is mostly caused by misinterpretations of the relevant religions' ethical rules and a combination of non-religious factors.[103][104][105][106] This includes the claim that events like terrorist bombings are more politically motivated than religious.[105][107][108] Mark Juergensmeyer argues that religion "does not ordinarily lead to violence.That happens only with the coalescence of a peculiar set of circumstances—political, social, and ideological—when religion becomes fused with violent expressions of social aspirations, personal pride, and movements for political change."[109]:10

Others have argued that it is unreasonable to attempt to differentiate "religious violence" and "secular violence" as separate categories since religion is not a universal and transhistorical phenomenon and neither is the secular.[110] Anthropologist Jack David Eller asserts that religion is not inherently violent, arguing "religion and violence are clearly compatible, but they are not identical." He asserts that "violence is neither essential to nor exclusive to religion" and that " virtually every form of religious violence has its non-religious corollary."[111]

It is also argued that the same violence happens in non-religious countries such as in communist Soviet Union, China, Cambodia.[112][113][106][114]

Suppression of scientific progress

John William Draper and Andrew Dickson White, authors of the conflict thesis, have argued that when a religion offers a complete set of answers to the problems of purpose, morality, origins, or science, it often discourages exploration of those areas by suppressing curiosity, denies its followers a broader perspective, and can prevent social, moral and scientific progress. Examples cited in their writings include the trial of Galileo and Giordano Bruno's execution.

During the 19th century the conflict thesis developed. According to this model, any interaction between religion and science must inevitably lead to open hostility, with religion usually taking the part of the aggressor against new scientific ideas.[117] The historical conflict thesis was a popular historiographical approach in the history of science during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but its original form is almost entirely discarded by scholars today.[118][119][120] Despite that, conflict theory remains a popular view among the general public,[121] and has been publicized by the success of books such as The God Delusion.

Historians of science including John Hedley Brooke and Ronald Numbers consider the "religion vs. science" concept an oversimplification, and prefer to take a more nuanced view of the subject.[121][122] These historians cite, for example, the Galileo affair[123] and the Scopes trial,[124] and assert that these were not purely instances of conflict between science and religion; personal and political factors also weighed heavily in the development of each. In addition, some historians contend that religious organizations figure prominently in the broader histories of many sciences, with many of the scientific minds until the professionalization of scientific enterprise (in the 19th century) being clergy and other religious thinkers.[125][126][127] Some historians contend that many scientific developments, such as Kepler's laws[128] and the 19th century reformulation of physics in terms of energy,[129] were explicitly driven by religious ideas.

Recent examples of tensions have been the creation-evolution controversy, controversies over the use of birth control, opposition to research into embryonic stem cells, or theological objections to vaccination, anesthesia, and blood transfusion.[130][131][132][133][134]

Arguments against religion suppressing science

Counterarguments against assumed conflict between the sciences and religions have been offered. For example, C. S. Lewis, a Christian, suggested that all religions, by definition, involve faith, or a belief in concepts that cannot be proven or disproven by the sciences. However, some religious beliefs have not been in line with views of the scientific community, for instance Young Earth creationism.[135] Though some who criticize religions subscribe to the conflict thesis, others do not. For example, Stephen Jay Gould agrees with C. S. Lewis and suggested that religion and science were non-overlapping magisteria.[136] Scientist Richard Dawkins has said that religious practitioners often do not believe in the view of non-overlapping magisteria (NOMA).[137]

However, research on perceptions of science among the American public concludes that most religious groups see no general epistemological conflict with science or with the seeking out of scientific knowledge, although there may be epistemic or moral conflicts when scientists make counterclaims to religious tenets.[138][139] Even strict creationists tend to have very favorable views on science.[140] Also, cross-national studies, polled from 1981-2001, on views of science and religion have noted that countries with higher religiosity have stronger trust in science, whereas countries that are seen as more secular are more skeptical about the impact of science and technology.[141] Though the United States is a highly religious country compared to other advanced industrial countries, according to the National Science Foundation, public attitudes towards science are more favorable in the United States than Europe, Russia, and Japan.[140] A study on a national sample of US college students examined whether they viewed the science / religion relationship as reflecting primarily conflict, collaboration, or independence. The study concluded that the majority of undergraduates in both the natural and social sciences do not see conflict between science and religion. Another finding in the study was that it is more likely for students to move away from a conflict perspective to an independence or collaboration perspective than vice versa.[142]

Counterarguments to religion as harmful to society

One study notes that significant levels of social dysfunction are found in highly religious countries such as the US and that countries which have lower religiosity also tend to have lower levels of dysfunction though it is noted in a later edition that correlation does not necessarily imply causation.[143][144][145]

Other studies show positive links in the relationship between religiosity and moral behavior, artruism and crime.[146][147][148][149][150][151] Indeed, a meta-analysis of 60 studies on religion and crime concluded, "religious behaviors and beliefs exert a moderate deterrent effect on individuals' criminal behavior".[146] [147][148][152][153][154][155][156] One study revealed that, at least in the United States forty percent of worship service attenders volunteer regularly to help the poor and elderly as opposed to 15% of Americans who never attend services.[155] Moreover, religious individuals are more likely than non-religious individuals to volunteer for school and youth programs (36% vs. 15%), a neighborhood or civic group (26% vs. 13%), and for health care (21% vs. 13%).[155] Other research has shown similar correlations between religiosity and giving.[157][158][159][160][160][161][162] In similar surveys, those who attended church were also more likely to report that they were registered to vote, that they volunteered, that they personally helped someone who was homeless, and to describe themselves as "active in the community."[163]

Morality

Dawkins contends that theistic religions devalue human compassion and morality. In his view, the Bible contains many injunctions against following one's conscience over scripture, and positive actions are supposed to originate not from compassion, but from the fear of punishment.[34] Albert Einstein stated that no religious basis is needed in order to display ethical behavior.[164]

Survey research suggests that believers do tend to hold different views than non-believers on a variety of social, ethical and moral questions. According to a 2003 survey conducted in the United States by The Barna Group, those who described themselves as believers were less likely than those describing themselves as atheists or agnostics to consider the following behaviors morally acceptable: cohabitating with someone of the opposite sex outside of marriage, enjoying sexual fantasies, having an abortion, sexual relationships outside of marriage, gambling, looking at pictures of nudity or explicit sexual behavior, getting drunk, and "having a sexual relationship with someone of the same sex."[165]

Children

In the 19th century, philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer argued that teaching some ideas to children at a young age could foster resistance to doubting those ideas later on.[166]

Islam[167] has permitted the child marriage of older men to girls as young as 9 years of age. Baptist pastor Jerry Vines has cited the age of one of Muhammad's wives, Aisha, to denounce him for having had sex with a nine-year-old, referring to Muhammad as a pedophile.[168]

The Seyaj Organization for the Protection of Children describes cases of a 10-year-old girl being married and raped in Yemen (Nujood Ali),[169] a 13-year-old Yemeni girl dying of internal bleeding three days after marriage,[170][171] and a 12-year-old girl dying in childbirth after marriage.[167][172] Yemen currently does not have a minimum age for marriage.[173]

Latter Day Saint church founder Joseph Smith married girls as young as 13 and 14,[174] and other Latter Day Saints married girls as young as 10.[175] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints eliminated underaged marriages in the 19th century, but several branches of Mormonism continue the practice.[176]

Homosexuals

Unlike many other religions, Hinduism does not view homosexuality as an issue.[177]

In the United States, conservative Christian right groups such as the Christian Legal Society and the Alliance Defense Fund have filed numerous lawsuits against public universities, aimed at overturning policies that protect homosexuals from discrimination and hate speech. These groups argue that such policies infringe their right to freely exercise religion as guaranteed by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution.[178]

Homosexuality is illegal in most Muslim countries, and several of these countries impose the death penalty for homosexual behavior. In July 2005, two Iranian men, aged sixteen and eighteen, were publicly hanged for homosexuality, causing an international outcry.[179]

Racism

Religion has been used by some as justification for advocating racism. The Christian Identity movement has been associated with racism.[180] There are arguments, however, that these positions may be as much reflections of contemporary social views as of what has been called scientific racism.[181]

The LDS Church excluded blacks from the priesthood in the church, from 1860 to 1978.[182] Most Fundamentalist Mormon sects within the Latter Day Saint movement, rejected the LDS Church's 1978 decision to allow African Americans to hold the priesthood, and continue to deny activity in the church due to race.[183] Due to these beliefs, in its Spring 2005 "Intelligence Report", the Southern Poverty Law Center named the FLDS Church to its "hate group" listing[184] because of the church's teachings on race, which include a fierce condemnation of interracial relationships.

On the other hand, many Christians have made efforts toward establishing racial equality, contributing to the Civil Rights Movement.[185] The African American Review sees as important the role Christian revivalism in the black church played in the Civil Rights Movement.[186] Martin Luther King, Jr., an ordained Baptist minister, was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement and president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, a Christian Civil Rights organization.[187]

Women

Islamic laws have been criticized by human rights organizations for exposing women to mistreatment and violence, preventing women from reporting rape, and contributing to the discrimination of women.[188] The United Nations say that Islam is used to justify unnecessary and harmful female genital mutilation (FGM), when the purposes range from deprivation of sexual satisfaction to discourage adultery, insuring virginity to their husbands, or generating appearance of virginity.[189] Maryam Namazie argues that women are victimized under Sharia law, both in criminal matters (such as punishment for improper veiling) and in civil matters, and also that women have judicial hurdles that are lenient or advantageous for men.[190]

According to Phyllis Chesler, Islam is connected to violence against women, especially in the form of honor killings. She rejects the argument that honor killings are not related to Islam, and claims that while fundamentalists of all religions place restrictions on women, in Islam not only are these restrictions harsher, but Islam also reacts more violently when these rules are broken.[191]

Christianity has been criticized for painting women as sinful, untrustful, deceiving, and desiring to seduce and incite men into sexual sin.[192] Katharine M. Rogers argues that Christianity is misogynistic, and that the "dread of female seduction" can be found in St. Paul's epistles.[193] K. K. Ruthven argues that the "legacy of Christian misogyny was consolidated by the so-called 'Fathers' of the Church, like Tertullian, who thought a woman was not only 'the gateway of the devil' but also 'a temple built over a sewer'."[194] Jack Holland argues the concept of fall of man is misogynistic as "a myth that blames woman for the ills and sufferings of mankind".[195]

According to Polly Toynbee, religion interferes with physical autonomy, and fosters negative attitudes towards women's bodies. Toynbee writes that "Women's bodies are always the issue - too unclean to be bishops, and dangerous enough to be covered up by Islam and mikvahed by Judaism".[196]

One criticism of religion is that it contributes to unequal relations in marriage, creating norms which subordinate the wife to the husband. The word בעל (ba`al), Hebrew for husband, used throughout the Bible, is synonymous with owner and master.[197]

Feminist Julie Bindel argues that religions encourage the domination of men over women, and that Islam promotes the submission of women to their husbands, and encourages practices such as child marriage. She wrote that religion "promotes inequality between men and women", that Islam's message for a woman includes that "she will be subservient to her husband and devote her life to pleasing him", and that "Islam's obsession with virginity and childbirth has led to gender segregation and early marriage.[198] Another feminist criticism of religion is the portrayal of God as an omnipotent, perfect power, where this power is one of domination, which is persistently associated with the characteristics of ideal masculinity.[199] Sheila Jeffreys argues that "Religion gives authority to traditional, patriarchal beliefs about the essentially subordinate nature of women and their naturally separate roles, such as the need for women to be confined to the private world of the home and family, that women should be obedient to their husbands, that women's sexuality should be modest and under the control of their menfolk, and that women should not use contraception or abortion to limit their childbearing. The practice of such ancient beliefs interferes profoundly with women's abilities to exercise their human rights".[200]

Christian religious figures have been involved in the Middle Ages and early modern period Witch trials, which were generally used to punish assertive or independent women, such as midwives, since witchcraft was often not in evidence,[201] or activists.[202]

Animals

Kosher slaughter has historically attracted criticism from non-Jews as allegedly being inhumane and unsanitary,[203] in part as an antisemitic canard that eating ritually slaughtered meat caused degeneration,[204] and in part out of economic motivation to remove Jews from the meat industry.[203] Sometimes, however, these criticisms were directed at Judaism as a religion. In 1893, animal advocates campaigning against kosher slaughter in Aberdeen attempted to link cruelty with Jewish religious practice.[205] In the 1920s, Polish critics of kosher slaughter claimed that the practice actually had no basis in Scripture.[203] In contrast, Jewish authorities argue that the slaughter methods are based directly upon Genesis IX:3, and that "these laws are binding on Jews today."[206]

Supporters of kosher slaughter counter that Judaism requires the practice precisely because it is considered humane.[206] Research conducted by Temple Grandin and Joe M. Regenstein in 1994 concluded that, practiced correctly with proper restraint systems, kosher slaughter results in little pain and suffering, and notes that behavioral reactions to the incision made during kosher slaughter are less than those to noises such as clanging or hissing, inversion or pressure during restraint.[207] Those who practice and subscribe religiously and philosophically to Jewish vegetarianism disagree, stating that such slaughter is not required, while a number, including medieval scholars of Judaism such as Joseph Albo and Isaac Arama, regard vegetarianism as a moral ideal, not just out of a concern for animal welfare but also the slaughterer.[208]

Other forms of ritual slaughter, such as Islamic ritual slaughter, have also come under controversy. Logan Scherer, writing for PETA, said that animals sacrificed according to Islamic law can not be stunned before they are killed.[209] Muslims are only allowed to eat meat that has been killed according to Sharia law, and they say that Islamic law on ritual slaughter is designed to reduce the pain and distress that the animal suffers.[210]

According to the Farm Animal Welfare Council (FAWC), halal and kosher practices should be banned because when animals are not stunned before death, they suffer needless pain for up to 2 minutes. Muslims and Jews argue that loss of blood from slash to the throat renders the animals unconscious pretty quickly.[211]

Corrupt purposes of leaders

Corrupt or immoral leaders

Dominionism

The term dominionism is often used to describe a political movement among fundamentalist Christians. Critics view dominionism as an attempt to improperly impose Christianity as the national faith of the United States. It emerged in the late 1980s inspired by the book, film and lecture series, "Whatever Happened to the Human Race?" by Francis A. Schaeffer and C. Everett Koop.[212] Schaeffer's views influenced conservatives like Jerry Falwell, Tim LaHaye, John W. Whitehead, and although they represent different theological and political ideas, dominionists believe they have a Christian duty to take "control of a sinful secular society", either by putting fundamentalist Christians in office, or by introducing biblical law into the secular sphere.[130][213][214] Social scientists have used the word "dominionism" to refer to adherence to Dominion Theology[215][216][217] as well as to the influence in the broader Christian Right of ideas inspired by Dominion Theology.[215]

In the early 1990s, sociologist Sara Diamond[218][219] and journalist Frederick Clarkson[220][221] defined dominionism as a movement that, while including Dominion Theology and Christian Reconstructionism as subsets, is much broader in scope, extending to much of the Christian Right.[222] Beginning in 2004 with essayist Katherine Yurica,[223][224][225] a group of authors including journalist Chris Hedges[226][227][228] Marion Maddox,[229] James Rudin,[230] Sam Harris,[231] and the group TheocracyWatch[232] began applying the term to a broader spectrum of people than have sociologists such as Diamond.

Full adherents to reconstructionism are few and marginalized among conservative Christians.[233][234][235] The terms "dominionist" and "dominionism" are rarely used for self-description, and their usage has been attacked from several quarters. Chip Berlet wrote that "some critics of the Christian Right have stretched the term dominionism past its breaking point."[236] Sara Diamond wrote that "[l]iberals' writing about the Christian Right's take-over plans has generally taken the form of conspiracy theory."[237] Journalist Anthony Williams charged that its purpose is "to smear the Republican Party as the party of domestic Theocracy, facts be damned."[238] Stanley Kurtz labeled it "conspiratorial nonsense," "political paranoia," and "guilt by association,"[239] and decried Hedges' "vague characterizations" that allow him to "paint a highly questionable picture of a virtually faceless and nameless 'Dominionist' Christian mass."[240] Kurtz also complained about a perceived link between average Christian evangelicals and extremism such as Christian Reconstructionism.[239]

See also

- A Brief History of Disbelief – 3-part PBS series (2007).

- Anthropology of religion

- Antireligion

- Antitheism

- Atheism

- Biblical inerrancy

- Christianity and violence

- Civil religion

- Cognitive dissonance

- Conversational intolerance

- Deism

- Development of religion

- Ethics without religion

- Folk religion

- God is dead

- Metaethics

- Morality without religion

- Philosophy of religion

- Problem of evil

- Theodicy

- Psychology of religion

- Rationalism

- Religion

- Religiosity and intelligence

- Religious belief

- Religious paranoia

- Religious satire

- Russell's teapot

- Social criticism

- Sociology of religion

- Supernatural

- Superstition

- Theism

- Theology

- True-believer syndrome

Criticism of specific religions and worldviews

- Controversies about Opus Dei

- Criticism of Atheism

- Criticism of Buddhism

- Criticism of Christianity

- Criticism of Hinduism

- Criticism of Islam

- Criticism of Jainism

- Criticism of Jehovah's Witnesses

- Criticism of Judaism

- Criticism of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

- Criticism of Sikhism

- Criticism of the Roman Catholic Church

- Scientology controversy

Notable critics of religion

References

- ↑ Beckford, James A. (2003). Social Theory and Religion. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 0-521-77431-4.

- ↑ See Saumur v Quebec (City of).

See also: "Human Rights in a Multicultural Society - Hate Speech". 9 February 2007.The Court has repeatedly stated that members of a religious community must tolerate the denial by others of their religious beliefs

Katharine Gelber; Adrienne Sarah Ackary Stone (2007). Hate Speech and Freedom of Speech in Australia. Federation Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-86287-653-8.In some belief systems, religious leaders and believers maintain the right to both emphasise the benefits of their own religion and criticise other religions; that is, they make their own claims and deny the truth claims of others.

Michael Herz; Peter Molnar (9 April 2012). The Content and Context of Hate Speech: Rethinking Regulation and Responses. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-37561-1.people of every religion, as well as of no religion, have a reason for wanting it to be possible to face other people with challenges to their faith, namely that this is the only way those people can be brought to see the truth.

"NO COMPULSION IN RELIGION: AN ISLAMIC CASE AGAINST BLASPHEMY LAWS" (PDF). Quilliam Foundation.Due to the nature of religious belief, one person's faith often implies that another's is wrong and perhaps even offensive, constituting blasphemy. For example, the major world religions often have very different formulations and beliefs concerning God, Muhammad, Jesus, Buddha and the Hindu deities, as well as about various ethical and social matters

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "religion". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- 1 2 3 4 Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 022618448X.

- 1 2 3 4 Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 030015416X.

- 1 2 Josephson, Jason Ananda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226412342.

- ↑ Max Müller, Natural Religion, p.33, 1889

- ↑ Lewis & Short, A Latin Dictionary

- ↑ Max Müller. Introduction to the science of religion. p. 28.

- ↑ Kuroda, Toshio and Jacqueline I. Stone, translator.""The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law"" (PDF). Archived from the original on March 23, 2003. Retrieved May 28, 2010. . Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23.3-4 (1996)

- ↑ Neil McMullin. Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.

- ↑ Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary, p.3, citing Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? ( Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).

- ↑ Linda M. Whiteford; Robert T. Trotter II (2008). Ethics for Anthropological Research and Practice. Waveland Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4786-1059-5.

- ↑ Titus Lucretius Carus. "De Rerum Natura". Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "Lucretius (c.99 – c.55 BCE)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2007-08-05.

- ↑ "Lucretius – Stanford Encyclopedia". Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ↑ Lucretius (1992). On the Nature of Things Translated by W.H.D. Rouse. Harvard University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-674-99200-8.

This (superstition) or "false religion", not "religion," is the meaning of "religio". The Epicureans were opposed, not to religion (cf. 6.68–79), but to traditional religion which taught that the gods govern the world. That Lucretius regarded "religio" as synonymous with "superstitio" is implied by "super....instans" in [line] 65.

- ↑ Middlemore, S. G. C.; Burckhardt, Jacob; Murray, Peter; Burke, Peter (1990). The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy. Penguin Classics. ISBN 0-14-044534-X.

- ↑ Machiavelli, Nicolo (1532). "The Prince". Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ↑ "Voltaire's Philosophical Dictionary". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ "Hume on Religion". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Bailey, David. "What are the merits of recent claims by atheistic scholars that modern science proves religion to be false and vain?".

- ↑ "The New Atheists". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ "The Vernon Atheist Display," Press Release, CT Valley Atheists, December 17, 2007 . Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ↑ White, Andrew D. (1993). A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom : Two volumes. Prometheus Books. ISBN 0879758260.

- ↑ Bart Ehrman; Misquoting Jesus, 166

- ↑ Bruce M. Metzger, The Text of the New Testament: its transmission, corruption, and restoration, pp. 199–200

- ↑ Brown, Raymond Edward (1999-05-18). The Birth of the Messiah: a commentary on the infancy narratives in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke. The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library. Yale University Press. p. 36. ISBN 0-300-14008-8.

- ↑ "History of The Quote". Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ↑ Narciso, Dianna (2003). Like Rolling Uphill: realizing the honesty of atheism. Coral Springs, FL: Llumina Press. p. 6. ISBN 1-932560-74-2.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel (2006). Breaking the Spell. Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9789-3.

- ↑ Harris, Sam (2005). The End of Faith. W. W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-32765-5.

- 1 2 3 Dawkins, Richard (2006). The God Delusion. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-618-68000-4.

- ↑ Lim, Chaeyoon; Puntam, Robert (2010). "Religion, Social Networks, and Life Satisfaction". American Sociological Review. 75 (6): 914–933. doi:10.1177/0003122410386686.

- ↑ Dennett, Daniel Clement (2006). Breaking the Spell : Religion as a Natural Phenomenon. Viking Adult. ISBN 0-670-03472-X.

- ↑ "When solar fears eclipse reason". BBC News. 2006-03-28. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ "Comets in Ancient Cultures". NASA.

- ↑ Onfray, Michel (2007). Atheist Manifesto: The Case Against Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. Arcade Publishing. ISBN 1-55970-820-4.

- 1 2 Marx, Karl (February 1844). "Introduction". A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel's Philosophy of Right. Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher.

- ↑ Marx, Karl (1867). Das Kapital. Volume 1, Part VIII.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2006). The Selfish Gene, 30th Anniversary edition.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (1991). "Viruses of the Mind".

- ↑ In his 1992–93 Gresham College lectures, written in collaboration with the psychiatrist Quinton Deeley and published as Is God a Virus?, SPCK, 1995, 274 pp. The quotes here come from p.73.

- ↑ Dawkins's God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life, p.125, quoting Simon Conway Morris in support

- ↑ Dawkins's God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life, p.126

- ↑ Dawkins's God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life, p.127

- ↑ Dawkins's God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life pp.137–138

- ↑ Dawkins's God: Genes, Memes and the Meaning of Life, p.136, citing Koenig and Cohen, The Link between Religion and Health, OUP, 2002.

- ↑ Harris, Sam (2005). The End of Faith. W.W. Norton. p. 73. ISBN 978-0-393-03515-5.

- ↑ "The Psychology of Mysticism". The Primal page.

- ↑ "Mysticism and Psychopathology". The Primal page.

- ↑ Atlas, Jerrold (2003). "Medieval Mystics' Lives As Self-Medication for Childhood Abuse".

- ↑ Pickover, Clifford (September–October 1999). The Vision of the Chariot: Transcendent Experience and Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. Science & Spirit.

- ↑ "God on the Brain". BBC Science & Nature.

- ↑ Shermer, Michael (1999-11-01). "Why People Believe in God: An Empirical Study on a Deep Question". American Humanist Association. p. 2. Retrieved 2006-04-05.

- ↑ Bradshaw, John (18 June 2006). "A God of the Gaps?". Ockham's Razor. ABC.

- ↑ Ward, Keith (2006). Is Religion Dangerous?. London:Lion Hudson Plc: Lion. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-7459-5262-8.

- ↑ Comte, Auguste. "Course of Positive Philosophy (1830)".

- ↑ Branden, N. (1963), "Mental Health versus Mysticism and Self-Sacrifice," Ayn Rand – The Virtue of Selfishness: A New Concept of Egoism.

- ↑ Asser, S. M.; Swan, R (1998-Apr; vol 101 (issue 4 Pt 1)). "Child fatalities from religion-motivated medical neglect". Pediatrics. 101 (4 Pt 1): 625–9. doi:10.1542/peds.101.4.625. PMID 9521945. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Jerusalem Syndrome: Jewish Virtual Library".

- ↑ "Jerusalem Syndrome".

- ↑ Bar-el Y, Durst R, Katz G, Zislin J, Strauss Z, Knobler H (2000). "Jerusalem syndrome". British Journal of Psychiatry. 176 (1): 86–90. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.1.86.

- 1 2 Kalian M, Witztum E (2000). "Comments on Jerusalem syndrome". British Journal of Psychiatry. 176 (5): 492. doi:10.1192/bjp.176.5.492-a.

- ↑ Tannock C, Turner T. (1995) Psychiatric tourism is overloading London beds. BMJ 1995;311:806 Full Text

- ↑ Kalian M, Witztum E (1999). "The Jerusalem syndrome"—fantasy and reality a survey of accounts from the 19th and 20th centuries". Isr. J. Psychiatry Relat Sci. 36 (4): 260–71. PMID 10687302.

- ↑ "Ethics - Honour crimes". BBC. 1970-01-01. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- 1 2 Hilary Mantell Thousands of Women Killed for Family "Honor". National Geographic News. February 12, 2002

- ↑ "International Domestic Violence Issues". Sanctuary For Families. Archived from the original on 2014-10-16. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- ↑ Handley, Paul (11 Sep 2010). "Islamic countries under pressure over stoning". AFP. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions about Stoning". violence is not our culture. Retrieved 14 May 2013.

- ↑ Sommerville, Quentin (26 Jan 2011). "Afghan police pledge justice for Taliban stoning". BBC. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ Nebehay, Stephanie (10 Jul 2009). "Pillay accuses Somali rebels of possible war crimes". Times of India. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ "Iran 'adulterer' stoned to death". BBC News. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ↑ "Iran denies execution by stoning". BBC News. 11 January 2005. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ↑ "Iran to scrap death by stoning". AFP. August 6, 2008. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ↑ «سنگسار» در شرع حذف شدنی نیست

- ↑ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/

- ↑ Rudin, Mike (30 April 2006). "The science of happiness". BBC. Retrieved 2010-01-02.

- ↑ Paul, Pamela (9 January 2005). "The New Science of Happiness". Time.

- ↑ Ward, Keith. Is Religion Dangerous?, p.156, citing David Myers The Science of Subjective Well-Being, Guilford Press, 2007.

- ↑ Smith, Timothy; McCullough, Michael; Poll, Justin (2003). "Religiousness and Depression: Evidence for a Main Effect and Moderating Influence of Stressful Life Events". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (4): 614–36. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. PMID 12848223.

- ↑ Bryan Johnson & colleagues at the University of Pennsylvania (2002)

- ↑ Is Religion Dangerous? cites similar results from the Handbook of Religion and Mental Health, Harold Koenig (ed.) ISBN 978-0-12-417645-4

- ↑ e.g. a survey Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. by Robert Putnam showing that membership of religious groups was positively correlated with membership of voluntary organizations

- ↑ Is Religion Dangerous?, Chapter 9.

- ↑ Hackney, Charles H.; Sanders, Glenn S. (2003). "Religiosity and Mental Health: A Meta–Analysis of Recent Studies". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 42 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160.

- ↑ Clark, A. E., & Lelkes, O. (January 2009). "Let us pray: religious interactions in life satisfaction", working paper no. 2009-01. Paris-Jourdan Sciences Economiques. Abstract retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ↑ Moreira-Almeida, Alexander; Neto, Francisco Lotufo; Koenig, Harold G. (September 2006). "Religiousness and mental health: a review". Rev. Bras. Psiquiatr. 28 (3): 242–250. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462006005000006. PMID 16924349.

- ↑ Koenig HG, McCullough M, Larson DB (2001). Handbook of Religion and Health. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Snoep, Liesbeth (6 February 2007). "Religiousness and happiness in three nations: a research note". Journal of Happiness Studies.

- ↑ Ronald Inglehart (2010). "Faith and Freedom: Traditional and Modern Ways to Happiness". In Diener, John F.; Helliwell, Daniel Kahneman. International Differences in Well-Being. Oxford University Press. pp. 378–385. ISBN 978-0-19-973273-9.

- ↑ "World Happiness Report 2013" (PDF). Columbia University. pp. 71–72.

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (April 1999). "A Designer Universe?". PhysLink.com. Washington, D.C. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

With or without religion, good people can behave well and bad people can do evil; but for good people to do evil — that takes religion.

- ↑ Russell, Bertrand. "Has Religion Made Useful Contributions to Civilization?". Retrieved 2009-10-23.

- ↑ Hartung, John (1995). "Love Thy Neighbour, The Evolution of In-Group Morality". Skeptic. 3 (5).

- ↑ Julian Glover. "Religion does more harm than good - poll". the Guardian. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- 1 2 Juergensmeyer, Mark (2001-09-21). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. Updated edition. University of California Press.

- ↑ "Christian Jihad: The Crusades and Killing in the Name of Christ". Cbn.com. 1998-02-23. Retrieved 2011-10-08.

- ↑ "Kill Them All; For The Lord Knoweth Them That Are His Steve Locks (Reply) (9-00)". Retrieved 2007-08-18.

- ↑ "Cover Story – businesstoday – February 2007". Apexstuff.com. 1947-01-24. Archived from the original on 2008-03-11. Retrieved 2009-10-24.

- ↑ Kabbani, Hisham; Seraj Hendricks; Ahmad Hendricks. "Jihad — A Misunderstood Concept from Islam".

- ↑ Esposito, John (2005), Islam: The Straight Path, p.93.

- 1 2 Pape, Robert (2005). Dying to Win: The Strategic Logic of Suicide Terrorism. New York, New York: Random House. ISBN 1-4000-6317-5.

- 1 2 Orr, H. Allen (1999). "Gould on God". bostonreview.net. Retrieved 24 January 2009.

- ↑ "Terrorism: The Current Threat", The Brookings Institution, Washington, DC, 10 February 2000.

- ↑ Nardin, Terry (May 2001). "Review of Terror in the Mind of God". The Journal of Politics. Southern Political Science Association. 64 (2): 683–684.

- ↑ Mark Juergensmeyer (2004). Terror in the Mind of God: The Global Rise of Religious Violence. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24011-1.

- ↑ Cavanaugh, William (2009). The Myth of Religious Violence. Oxford University Press US,.

- ↑ Eller, Jack David (2010). Cruel Creeds, Virtuous Violence: Religious Violence Across Culture and History. Prometheus Books. ISBN 978-1-61614-218-6.

- ↑ Feinberg, John S.; Feinberg, Paul D. (2010-11-04). Ethics for a Brave New World. Crossway Books. ISBN 978-1-58134-712-8. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

Over a half century ago, while I was still a child, I recall hearing a number of old people offer the following explanation for the great disasters that had befallen Russia: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.' Since then I have spent well-nigh 50 years working on the history of our revolution; in the process I have read hundreds of books, collected hundreds of personal testimonies, and have already contributed eight volumes of my own toward the effort of clearing away the rubble left by that upheaval. But if I were asked today to formulate as concisely as possible the main cause of the ruinous revolution that swallowed up some 60 million of our people, I could not put it more accurately than to repeat: 'Men have forgotten God; that's why all this has happened.'

- ↑ Koukl, Gregory. "The Real Murderers: Atheism or Christianity?". Stand To Reason. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

- ↑ D'Souza, Dinesh. "Answering Atheist's Arguments". Catholic Education Resource Center. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

And who can deny that Stalin and Mao, not to mention Pol Pot and a host of others, all committed atrocities in the name of a Communist ideology that was explicitly atheistic? Who can dispute that they did their bloody deeds by claiming to be establishing a 'new man' and a religion-free utopia? These were mass murders performed with atheism as a central part of their ideological inspiration, they were not mass murders done by people who simply happened to be atheist.

- ↑ Baroque Routes. p. 16.

- ↑ De Lucca, Denis (2015). Tomaso Maria Napoli: A Dominican friar's contribution to Military Architecture in the Baroque Age. International Institute for Baroque Studies: UOM. p. 254. ISBN 9789995708375.

- ↑ Wilson, David B. (2002). "The Historiography of Science and Religion". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

- ↑ Russell, Colin A. (2002). "The Conflict Thesis". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 7. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

The conflict thesis, at least in its simple form, is now widely perceived as a wholly inadequate intellectual framework within which to construct a sensible and realistic historiography of Western science

- ↑ Shapin, S. (1996). The Scientific Revolution. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 195.

In the late Victorian period it was common to write about the ‘warfare between science and religion’ and to presume that the two bodies of culture must always have been in conflict. However, it is a very long time since these attitudes have been held by historians of science

- ↑ Brooke, J.H. (1991). Science and Religion: Some Historical Perspectives. Cambridge University Press. p. 42.

In its traditional forms, the conflict thesis has been largely discredited.

- 1 2 Ferngren, Gary (2002). "Introduction". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. x. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

while [John] Brooke's view [of a complexity thesis rather than an historical conflict thesis] has gained widespread acceptance among professional historians of science, the traditional view remains strong elsewhere, not least in the popular mind

- ↑ Russell, Colin A. (2002). "The Conflict Thesis". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

The conflict thesis, at least in its simple form, is perceived by some historians as a wholly inadequate intellectual framework within which to construct a sensible and realistic historiography of Western science.

- ↑ Blackwell, Richard J. (2002). "Galileo Galilei". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

- ↑ Larson, Edward J. (1997). Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Battle over Science and Religion. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Rupke, Nicolaas A. (2002). "Geology and Paleontology". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

- ↑ Hess, Peter M. (2002). "Natural History". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

- ↑ Moore, James (2002). "Charles Darwin". In Gary Ferngren. Science & Religion: A Historical Introduction. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-7038-0.

- ↑ Barker, Peter; Goldstein, Bernard R. (2001). "Theological Foundations of Kepler's Astronomy". Osiris. Science in Theistic Contexts. 16. University of Chicago Press. pp. 88–113.

- ↑ Smith, Crosbie (1998). The Science of Energy: A Cultural History of Energy Physics in Victorian Britain. London: The Athlone Press.

- 1 2 Berlet, Chip. "Following the Threads," in Ansell, Amy E. Unraveling the Right: The New Conservatism in American Thought and Politics, pp. 24, Westview Press, 1998, ISBN 0-8133-3147-1

- ↑ "Humanae Vitae: Encyclical of Pope Paul VI on the Regulation of Birth, July 25, 1968". The Vatican. Archived from the original on March 18, 2011. Retrieved 2006-10-01.

- ↑ "MPs turn attack back on Cardinal Pell". Sydney Morning Herald. 2007-06-06.

- ↑ "Pope warns Bush on stem cells". BBC News. 2001-07-23.

- ↑ Andrew Dickson, White (1898). A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom. p. X. Theological Opposition to Inoculation, Vaccination, and the Use of Anaesthetics.

- ↑ "IAP Statement on the teaching of evolution" (PDF). the Interacademy Panel on international issues. 2006. Retrieved 2007-07-03.

- ↑ Gould, Stephen Jay (2002). Rocks of Ages: Science and Religion in the Fullness of Life. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-45040-X.

- ↑ Dawkins, Richard (2007). The God Delusion (Paperback ed.). p. 77.

- ↑ Evans, John (2011). "Epistemological and Moral Conflict Between Religion and Science". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 50 (4): 707–727. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01603.x.

- ↑ Baker, Joseph O. (April 2012). "Public Perceptions of Incompatibility Between "Science and Religion"". Public Understanding of Science. 21 (3): 340–353. doi:10.1177/0963662511434908.

- 1 2 Keeter, Scott; Smith, Gregory; Masci, David (2011). "Religious Belief and Attitudes about Science in the United States". The Culture of science: How the Public Relates to Science Across the Globe. New York: Routledge. pp. 336, 345–346. ISBN 978-0415873697.

The United States is perhaps the most religious out of the advanced industrial democracies." ; "In fact, large majorities of the traditionally religious American nevertheless hold very positive views of science and scientists. Even people who accept a strict creationist view, regarding the origins of life are mostly favorable towards science." ; "According to the National Science Foundation, public attitudes about science are more favorable in the United States than in Europe, Russia, and Japan, despite great differences across these cultures in level of religiosity (National Science Foundation, 2008).

- ↑ Norris, Pippa; Ronald Inglehart (2011). Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 67–68. ISBN 978-1-107-64837-1.

- ↑ Christopher P. Scheitle (2011). "U.S. College students' perception of religion and science: Conflict, collaboration, or independence? A research note". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. Blackwell. 50 (1): 175–186. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2010.01558.x. ISSN 1468-5906.

- ↑ "Cross-National Correlations of Quantifiable Societal Health with Popular Religiosity and Secularism in the Prosperous Democracies". Retrieved 2007-10-30.

There is evidence that within the U.S. strong disparities in religious belief versus acceptance of evolution are correlated with similarly varying rates of societal dysfunction, the strongly theistic, anti-evolution south and mid-west having markedly worse homicide, mortality, STD, youth pregnancy, marital and related problems than the northeast where societal conditions, secularization, and acceptance of evolution approach European norms.

- ↑ Moreno-Riaño, Gerson; Smith, Mark Caleb; Mach, Thomas (2006). "Religiosity, Secularism, and Social Health" (PDF). Journal of Religion and Society. Cedarville University. 8.

- ↑ Jensen, Gary F. (2006) Religious Cosmologies and Homicide Rates among Nations: A Closer Look Archived December 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine., Journal of Religion and Society, Department of Sociology, Vanderbilt University, Vol. 8, ISSN 1522-5658

- 1 2 Kerley, Kent R.; Matthews, Todd L.; Blanchard, Troy C. (2005). "Religiosity, Religious Participation, and Negative Prison Behaviors". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 44 (4): 443–457. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00296.x.

- 1 2 Saroglou, Vassilis; Pichon, Isabelle; Trompette, Laurence; Verschueren, Marijke; Dernelle, Rebecca (2005). "Prosocial Behavior and Religion: New Evidence Based on Projective Measures and Peer Ratings". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 44 (3): 323–348. doi:10.1111/j.1468-5906.2005.00289.x.

- 1 2 Regnerus, Mark D.; Burdette, Amy (2006). "Religious Change and Adolescent Family Dynamics". The Sociological Quarterly. 47 (1): 175–194. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00042.x.

- ↑ for example, a survey Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. by Robert Putnam showing that membership of religious groups was positively correlated with membership of voluntary organisations

- ↑ As is stated in: Doris C. Chu (2007). Religiosity and Desistance From Drug Use" Criminal Justice and Behavior 2007; 34; 661 originally published online Mar 7, 2007; doi:10.1177/0093854806293485

- ↑ For example:

- Albrecht, S. I.; Chadwick, B. A.; Alcorn, D. S. (1977). "Religiosity and deviance:Application of an attitude-behavior contingent consistency model". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 16 (3): 263–274. doi:10.2307/1385697.

- Burkett, S.; White, M. (1974). "Hellfire and delinquency:Another look". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 13 (4): 455–462. doi:10.2307/1384608.

- Chard-Wierschem, D. (1998). In pursuit of the "true" relationship: A longitudinal study of the effects of religiosity on delinquency and substance abuse. Ann Arbor, MI: UMI Dissertation.

- Cochran, J. K.; Akers, R. L. (1989). "Beyond hellfire:An explanation of the variable effects of religiosity on adolescent marijuana and alcohol use". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 26 (3): 198–225. doi:10.1177/0022427889026003002.

- Evans, T. D.; Cullen, F. T.; Burton, V. S.; Jr; Dunaway, R. G.; Payne, G. L.; Kethineni, S. R. (1996). "Religion, social bonds, and delinquency". Deviant Behavior. 17: 43–70. doi:10.1080/01639625.1996.9968014.

- Grasmick, H. G.; Bursik, R. J.; Cochran, J. K. (1991). "Render unto Caesar what is Caesar's": Religiosity and taxpayer's inclinations to cheat". The Sociological Quarterly. 32: 251–266. doi:10.1111/j.1533-8525.1991.tb00356.x.

- Higgins, P. C.; Albrecht, G. L. (1977). "Hellfire and delinquency revisited". Social Forces. 55: 952–958. doi:10.1093/sf/55.4.952.

- Johnson, B. R.; Larson, D. B.; DeLi, S.; Jang, S. J. (2000). "Escaping from the crime of inner cities:Church attendance and religious salience among disadvantaged youth". Justice Quarterly. 17: 377–391. doi:10.1080/07418820000096371.

- Johnson, R. E.; Marcos, A. C.; Bahr, S. J. (1987). "The role of peers in the complex etiology of adolescent drug use". Criminology. 25: 323–340. doi:10.1111/j.1745-9125.1987.tb00800.x.

- Powell, K (1997). "Correlates of violent and nonviolent behavior among vulnerable inner-city youths". Family and Community Health. 20: 38–47. doi:10.1097/00003727-199707000-00006.

- ↑ Baier, C. J.; Wright, B. R. (2001). "If you love me, keep my commandments":A meta-analysis of the effect of religion on crime". Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 38: 3–21. doi:10.1177/0022427801038001001.

- ↑ Conroy, S. J.; Emerson, T. L. N. (2004). "Business Ethics and Religion: Religiosity as a Predictor of Ethical Awareness Among Students". Journal of Business Ethics. 50 (4): 383–396. doi:10.1023/B:BUSI.0000025040.41263.09.

- ↑ e.g. a survey Archived October 8, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. by Robert Putnam showing that membership of religious groups was positively correlated with membership of voluntary organizations

- 1 2 3 "Religious people make better citizens, study says". Pew Research Center. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

The scholars say their studies found that religious people are three to four times more likely to be involved in their community. They are more apt than nonreligious Americans to work on community projects, belong to voluntary associations, attend public meetings, vote in local elections, attend protest demonstrations and political rallies, and donate time and money to causes – including secular ones. At the same time, Putnam and Campbell say their data show that religious people are just "nicer": they carry packages for people, don't mind folks cutting ahead in line and give money to panhandlers.

- ↑ Campbell, David; Putnam, Robert (2010-11-14). "Religious people are 'better neighbors'". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-10-18.

However, on the other side of the ledger, religious people are also "better neighbors" than their secular counterparts. No matter the civic activity, being more religious means being more involved. Take, for example, volunteer work. Compared with people who never attend worship services, those who attend weekly are more likely to volunteer in religious activities (no surprise there), but also for secular causes. The differences between religious and secular Americans can be dramatic. Forty percent of worship-attending Americans volunteer regularly to help the poor and elderly, compared with 15% of Americans who never attend services. Frequent-attenders are also more likely than the never-attenders to volunteer for school and youth programs (36% vs. 15%), a neighborhood or civic group (26% vs. 13%), and for health care (21% vs. 13%). The same is true for philanthropic giving; religious Americans give more money to secular causes than do secular Americans. And the list goes on, as it is true for good deeds such as helping someone find a job, donating blood, and spending time with someone who is feeling blue. Furthermore, the "religious edge" holds up for organized forms of community involvement: membership in organizations, working to solve community problems, attending local meetings, voting in local elections, and working for social or political reform. On this last point, it is not just that religious people are advocating for right-leaning causes, although many are. Religious liberals are actually more likely to be community activists than are religious conservatives.

- ↑ Brooks, Arthur. "Religious Faith and Charitable Giving".

- ↑ Brooks, Arthur C. "Religious faith and charitable giving", Policy Review, Oct–Dec 2003.

- ↑ Will, George F. "Bleeding Hearts but Tight Fists", Washington Post, 27 March 2008; Page A17

- 1 2 Gose, Ben. "Charity's Political Divide" Archived April 29, 2009, at the Wayback Machine., The Chronicle of Philanthropy, 23 November 2006.

- ↑ Brooks, Arthur C. Who Really Cares: The Surprising Truth about Compassionate Conservatism, Basic Books, 27 November 2006. ISBN 0-465-00821-6

- ↑ Stossel, John; Kendall, Kristina (28 November 2006). "Who Gives and Who Doesn't? Putting the Stereotypes to the Test". ABC News.

- ↑ "Atheists and Agnostics Take Aim at Christians" Archived November 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine., The Barna Update, The Barna Group, 11 June 2007.

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1930-11-09). "Religion and Science". New York Times Magazine.

A man's ethical behavior should be based effectually on sympathy, education, and social ties; no religious basis is necessary. Man would indeed be in a poor way if he had to be restrained by fear of punishment and hope of reward after death.