Happiness

Happiness is a mental or emotional state of well-being defined by positive or pleasant emotions ranging from contentment to intense joy.[1] Happy mental states may also reflect judgements by a person about their overall well-being.[2] A variety of biological, psychological, economic, religious and philosophical approaches have striven to define happiness and identify its sources. Various research groups, including positive psychology and happiness economics are employing the scientific method to research questions about what "happiness" is, and how it might be attained.

The United Nations declared 20 March the International Day of Happiness to recognise the relevance of happiness and well-being as universal goals.

Definition

Philosophers and religious thinkers often define happiness in terms of living a good life, or flourishing, rather than simply as an emotion. Happiness in this sense was used to translate the Greek eudaimonia, and is still used in virtue ethics. There has been a transition over time from emphasis on the happiness of virtue to the virtue of happiness.[3] Since the turn of the millennium, the human flourishing approach, advanced particularly by Amartya Sen has attracted increasing interest in psychological, especially prominent in the work of Martin Seligman, Ed Diener and Ruut Veenhoven, and international development and medical research in the work of Paul Anand.

A widely discussed political value expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, written by Thomas Jefferson, is the universal right to "the pursuit of happiness."[4] This seems to suggest a subjective interpretation but one that nonetheless goes beyond emotions alone. In fact, this discussion is often based on the naive assumption that the word happiness meant the same thing in 1776 as it does today, an error committed even by history professors such as Arthur Schlesinger, as cited in the previous source. In fact, happiness meant "prosperity, thriving, wellbeing" in the 18th century.[5]

Nowadays, happiness is a fuzzy concept and can mean many different things to many people. Part of the challenge of a science of happiness is to identify different concepts of happiness, and where applicable, split them into their components. Related concepts are well-being, quality of life and flourishing. At least one author defines happiness as contentment.[6] Some commentators focus on the difference between the hedonistic tradition of seeking pleasant and avoiding unpleasant experiences, and the eudaimonic tradition of living life in a full and deeply satisfying way.[7]

The 2012 World Happiness Report stated that in subjective well-being measures, the primary distinction is between cognitive life evaluations and emotional reports.[8] Happiness is used in both life evaluation, as in “How happy are you with your life as a whole?”, and in emotional reports, as in “How happy are you now?,” and people seem able to use happiness as appropriate in these verbal contexts. Using these measures, the World Happiness Report identifies the countries with the highest levels of happiness.

Research results

Since the 1960s, happiness research has been conducted in a wide variety of scientific disciplines, including gerontology, social psychology, clinical and medical research and happiness economics. During the past two decades, however, the field of happiness studies has expanded drastically in terms of scientific publications, and has produced many different views on causes of happiness, and on factors that correlate with happiness,[9] but no validated method has been found to substantially improve long-term happiness in a meaningful way for most people.

Sonja Lyubomirsky concludes in her book The How of Happiness that 50 percent of a given human's happiness level is genetically determined (based on twin studies), 10 percent is affected by life circumstances and situation, and a remaining 40 percent of happiness is subject to self-control.

Biological psychologist Meike Bartels also concluded that happiness is partly genetically based.[10][11]

The results of the 75-year Grant Study of Harvard undergraduates show a high correlation of loving relationship, especially with parents, with later life wellbeing.[12]

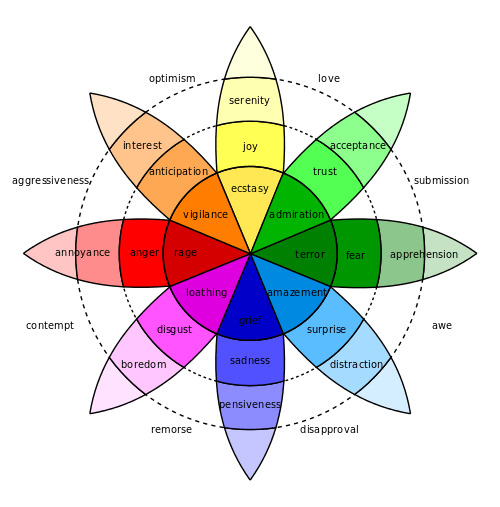

In the 2nd Edition of the Handbook of Emotions (2000), evolutionary psychologists Leda Cosmides and John Tooby say that happiness comes from "encountering unexpected positive events". In the 3rd Edition of the Handbook of Emotions (2008), Michael Lewis says "happiness can be elicited by seeing a significant other". According to Mark Leary, as reported in a November 1995 issue of Psychology Today, "we are happiest when basking in the acceptance and praise of others". Sara Algoe and Jonathan Haidt say that "happiness" may be the label for a family of related emotional states, such as joy, amusement, satisfaction, gratification, euphoria, and triumph.[13]

It has been argued that money cannot effectively "buy" much happiness unless it is used in certain ways.[14] "Beyond the point at which people have enough to comfortably feed, clothe, and house themselves, having more money - even a lot more money - makes them only a little bit happier." In the book Lucky Go Happy : Make Happiness Happen!, Paul van der Merwe uses a graph to illustrate that money cannot make people happy.[15] A Harvard Business School study found that "spending money on others actually makes us happier than spending it on ourselves".[16]

Meditation has been found to lead to high activity in the brain's left prefrontal cortex, which in turn has been found to correlate with happiness.[17]

Psychologist Martin Seligman asserts that happiness is not solely derived from external, momentary pleasures,[18] and provides the acronym PERMA to summarize Positive Psychology's correlational findings: humans seem happiest when they have

- Pleasure (tasty food, warm baths, etc.),

- Engagement (or flow, the absorption of an enjoyed yet challenging activity),

- Relationships (social ties have turned out to be extremely reliable indicator of happiness),

- Meaning (a perceived quest or belonging to something bigger), and

- Accomplishments (having realized tangible goals).

There have also been some studies of how religion relates to happiness. Causal relationships remain unclear, but more religion is seen in happier people. This correlation may be the result of community membership and not necessarily belief in religion itself. Another component may have to do with ritual.[19]

Abraham Harold Maslow, an American professor of psychology, founded humanistic psychology in the 1930s. A visual aid he created to explain his theory, which he called the hierarchy of needs, is a pyramid depicting the levels of human needs, psychological, and physical. When a human being ascends the steps of the pyramid, he reaches self-actualization. Beyond the routine of needs fulfillment, Maslow envisioned moments of extraordinary experience, known as peak experiences, profound moments of love, understanding, happiness, or rapture, during which a person feels more whole, alive, self-sufficient, and yet a part of the world. This is similar to the flow concept of Mihály Csíkszentmihályi.

Self-determination theory relates intrinsic motivation to three needs: competence, autonomy, and relatedness.

Cross-sectional studies worldwide support a relationship between happiness and fruit and vegetable intake. Those eating fruits and vegetables each day have a higher likelihood of being classified as “very happy,” suggesting a strong and positive correlation between fruit and vegetable consumption and happiness.[20] Whether it be in South Korea,[21] Iran,[22] Chile,[23] USA,[24] or UK,[25] greater fruit and vegetable consumption had a positive association with greater happiness, independent of factors such as smoking, exercise, body mass index, or socio-economic factors.

Religion

Religion and happiness have been studied by a number of researchers, and religion features many elements addressing the components of happiness, as identified by positive psychology. Its association with happiness is facilitated in part by the social connections of organized religion,[26] and by the neuropsychological benefits of prayer[27] and belief.

There are a number of mechanisms through which religion may make a person happier, including social contact and support that result from religious pursuits, the mental activity that comes with optimism and volunteering, learned coping strategies that enhance one's ability to deal with stress, and psychological factors such as "reason for being." It may also be that religious people engage in behaviors related to good health, such as less substance abuse, since the use of psychotropic substances is sometimes considered abuse.[28][29][30][31][32][33]

The Handbook of Religion and Health describes a survey by Feigelman (1992) that examined happiness in Americans who have given up religion, in which it was found that there was little relationship between religious disaffiliation and unhappiness.[34] A survey by Kosmin & Lachman (1993), also cited in this handbook, indicates that people with no religious affiliation appear to be at greater risk for depressive symptoms than those affiliated with a religion.[35] A review of studies by 147 independent investigators found, "the correlation between religiousness and depressive symptoms was -.096, indicating that greater religiousness is mildly associated with fewer symptoms."[36]

The Legatum Prosperity Index reflects the repeated finding of research on the science of happiness that there is a positive link between religious engagement and wellbeing: people who report that God is very important in their lives are on average more satisfied with their lives, after accounting for their income, age and other individual characteristics.[37]

Surveys by Gallup, the National Opinion Research Centre and the Pew Organisation conclude that spiritually committed people are twice as likely to report being "very happy" than the least religiously committed people.[38] An analysis of over 200 social studies contends that "high religiousness predicts a lower risk of depression and drug abuse and fewer suicide attempts, and more reports of satisfaction with sex life and a sense of well-being. However, the links between religion and happiness are always very broad in nature, highly reliant on scripture and small sample number. To that extent there is a much larger connection between religion and suffering (Lincoln 1034)."[36] And a review of 498 studies published in peer-reviewed journals concluded that a large majority of them showed a positive correlation between religious commitment and higher levels of perceived well-being and self-esteem and lower levels of hypertension, depression, and clinical delinquency.[39] A meta-analysis of 34 recent studies published between 1990 and 2001 found that religiosity has a salutary relationship with psychological adjustment, being related to less psychological distress, more life satisfaction, and better self-actualization.[40] Finally, a recent systematic review of 850 research papers on the topic concluded that "the majority of well-conducted studies found that higher levels of religious involvement are positively associated with indicators of psychological well-being (life satisfaction, happiness, positive affect, and higher morale) and with less depression, suicidal thoughts and behaviour, drug/alcohol use/abuse."[41]

However, there remains strong disagreement among scholars about whether the effects of religious observance, particularly attending church or otherwise belonging to religious groups, is due to the spiritual or the social aspects—i.e. those who attend church or belong to similar religious organizations may well be receiving only the effects of the social connections involved. While these benefits are real enough, they may thus be the same one would gain by joining other, secular groups, clubs, or similar organizations.[42]

Terror management

Terror management theory maintains that people suffer cognitive dissonance (anxiety) when they are reminded of their inevitable death. Through terror management, individuals are motivated to seek consonant elements – symbols which make sense of mortality and death in satisfactory ways (i.e. boosting self-esteem).

Research has found that strong belief in religious or secular meaning systems affords psychological security and hope. It is moderates (e.g. agnostics, slightly religious individuals) who likely suffer the most anxiety from their meaning systems. Religious meaning systems are especially adapted to manage death anxiety because they are unlikely to be disconfirmed (for various reasons), they are all encompassing, and they promise literal immortality.[43][44]

Whether emotional effects are beneficial or adverse seems to vary with the nature of the belief. Belief in a benevolent God is associated with lower incidence of general anxiety, social anxiety, paranoia, obsession, and compulsion whereas belief in a punitive God is associated with greater symptoms. (An alternative explanation is that people seek out beliefs that fit their psychological and emotional states.)[45]

Citizens of the world's poorest countries are the most likely to be religious, and researchers suggest this is because of religion's powerful coping abilities.[46][47] Luke Galen also supports terror management theory as a partial explanation of the above findings. Galen describes evidence (including his own research) that the benefits of religion are due to strong convictions and membership in a social group.[48][49][50]

Religious views on happiness

Buddhism

Happiness forms a central theme of Buddhist teachings.[51] For ultimate freedom from suffering, the Noble Eightfold Path leads its practitioner to Nirvana, a state of everlasting peace. Ultimate happiness is only achieved by overcoming craving in all forms. More mundane forms of happiness, such as acquiring wealth and maintaining good friendships, are also recognized as worthy goals for lay people (see sukha). Buddhism also encourages the generation of loving kindness and compassion, the desire for the happiness and welfare of all beings.[52][53]

Judaism

Happiness or simcha (Hebrew: שמחה) in Judaism is considered an important element in the service of God.[54] The biblical verse "worship The Lord with gladness; come before him with joyful songs," (Psalm 100:2) stresses joy in the service of God. A popular teaching by Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, a 19th-century Chassidic Rabbi, is "Mitzvah Gedolah Le'hiyot Besimcha Tamid," it is a great mitzvah (commandment) to always be in a state of happiness. When a person is happy they are much more capable of serving God and going about their daily activities than when depressed or upset.[55]

Catholicism

The primary meaning of "happiness" in various European languages involves good fortune, chance or happening. The meaning in Greek philosophy, however, refers primarily to ethics. In Catholicism, the ultimate end of human existence consists in felicity, Latin equivalent to the Greek eudaimonia, or "blessed happiness", described by the 13th-century philosopher-theologian Thomas Aquinas as a Beatific Vision of God's essence in the next life.[56] Human complexities, like reason and cognition, can produce well-being or happiness, but such form is limited and transitory. In temporal life, the contemplation of God, the infinitely Beautiful, is the supreme delight of the will. Beatitudo, or perfect happiness, as complete well-being, is to be attained not in this life, but the next.[57]

Spirituality

While religion is often formalised and community-oriented, spirituality tends to be individually based and not as formalised. In a 2014 study, 320 children, ages 8–12, in both public and private schools, were given a Spiritual Well-Being Questionnaire assessing the correlation between spirituality and happiness. Spirituality – and not religious practices (praying, attending church services) – correlated positively with the child's happiness; the more spiritual the child was, the happier the child was. Spirituality accounted for about 3–26% of the variance in happiness.[58]

Philosophical views

The Chinese Confucian thinker Mencius, who 2300 years ago sought to give advice to the ruthless political leaders of the warring states period, was convinced that the mind played a mediating role between the "lesser self" (the physiological self) and the "greater self" (the moral self) and that getting the priorities right between these two would lead to sage-hood. He argued that if we did not feel satisfaction or pleasure in nourishing one's "vital force" with "righteous deeds", that force would shrivel up (Mencius,6A:15 2A:2). More specifically, he mentions the experience of intoxicating joy if one celebrates the practice of the great virtues, especially through music.[59]

Al-Ghazali (1058–1111) the Muslim Sufi thinker wrote the Alchemy of Happiness, a manual of spiritual instruction throughout the Muslim world and widely practiced today.

The Hindu thinker Patanjali, author of the Yoga Sutras, wrote quite exhaustively on the psychological and ontological roots of bliss.[60]

In the Nicomachean Ethics, written in 350 BCE, Aristotle stated that happiness (also being well and doing well) is the only thing that humans desire for its own sake, unlike riches, honor, health or friendship. He observed that men sought riches, or honor, or health not only for their own sake but also in order to be happy. Note that eudaimonia, the term we translate as "happiness", is for Aristotle an activity rather than an emotion or a state.[61] Thus understood, the happy life is the good life, that is, a life in which a person fulfills human nature in an excellent way. Specifically, Aristotle argues that the good life is the life of excellent rational activity. He arrives at this claim with the Function Argument. Basically, if it's right, every living thing has a function, that which it uniquely does. For humans, Aristotle contends, our function is to reason, since it is that alone that we uniquely do. And performing one's function well, or excellently, is one's good. Thus, the life of excellent rational activity is the happy life. Aristotle does not leave it that, however. For he argues that there is a second best life for those incapable of excellent rational activity.This second best life is the life of moral virtue.

Many ethicists make arguments for how humans should behave, either individually or collectively, based on the resulting happiness of such behavior. Utilitarians, such as John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, advocated the greatest happiness principle as a guide for ethical behavior.

Friedrich Nietzsche savagely critiqued the English Utilitarians' focus on attaining the greatest happiness, stating "Man does not strive for happiness, only the Englishman does." Nietzsche meant that the making happiness one's ultimate goal, the aim of one's existence "makes one contemptible;" Nietzsche instead yearned for a culture that would set higher, more difficult goals than "mere happiness." Thus Nietzsche introduces the quasi-dystopic figure of the "last man" as a kind of thought experiment against the utilitarians and happiness-seekers; these small, "last men" who seek after only their own pleasure and health, avoiding all danger, exertion, difficulty, challenge, struggle are meant to seem contemptible to Nietzsche's reader. Nietzsche instead wants us to consider the value of what is difficult, what can only be earned through struggle, difficulty, pain and thus to come to see the affirmative value suffering and unhappiness truly play in creating everything of great worth in life, including all the highest achievements of human culture, not least of all philosophy.[62][63]

According to St. Augustine and Thomas Aquinas, man's last end is happiness: "all men agree in desiring the last end, which is happiness."[64] However, where utilitarians focused on reasoning about consequences as the primary tool for reaching happiness, Aquinas agreed with Aristotle that happiness cannot be reached solely through reasoning about consequences of acts, but also requires a pursuit of good causes for acts, such as habits according to virtue.[65] In turn, which habits and acts that normally lead to happiness is according to Aquinas caused by laws: natural law and divine law. These laws, in turn, were according to Aquinas caused by a first cause, or God.

According to Aquinas, happiness consists in an "operation of the speculative intellect": "Consequently happiness consists principally in such an operation, viz. in the contemplation of Divine things." And, "the last end cannot consist in the active life, which pertains to the practical intellect." So: "Therefore the last and perfect happiness, which we await in the life to come, consists entirely in contemplation. But imperfect happiness, such as can be had here, consists first and principally in contemplation, but secondarily, in an operation of the practical intellect directing human actions and passions."[66]

Economic and political views

Common market health measures such as GDP and GNP have been used as a measure of successful policy. On average richer nations tend to be happier than poorer nations, but this effect seems to diminish with wealth.[67][68] This has been explained by the fact that the dependency is not linear but logarithmic, i.e., the same percentual increase in the GNP produces the same increase in happiness for wealthy countries as for poor countries.[69][70][71][72] Increasingly, academic economists and international economic organisations are arguing for and developing multi-dimensional dashboards which combine subjective and objective indicators to provide a more direct and explicit assessment of human wellbeing. Work by Paul Anand and colleagues helps to highlight the fact that there many different contributors to adult wellbeing, that happiness judgement reflect, in part, the presence of salient constraints, and that fairness, autonomy, community and engagement are key aspects of happiness and wellbeing throughout the life course.

Libertarian think tank Cato Institute claims that economic freedom correlates strongly with happiness[73] preferably within the context of a western mixed economy, with free press and a democracy. According to certain standards, East European countries (ruled by Communist parties) were less happy than Western ones, even less happy than other equally poor countries.[74]

However, much empirical research in the field of happiness economics, such as that by Benjamin Radcliff, professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, supports the contention that (at least in democratic countries) life satisfaction is strongly and positively related to the social democratic model of a generous social safety net, pro-worker labor market regulations, and strong labor unions.[75] Similarly, there is evidence that public policies that reduce poverty and support a strong middle class, such as a higher minimum wage, strongly affects average levels of well-being.[76]

It has been argued that happiness measures could be used not as a replacement for more traditional measures, but as a supplement.[77] According to professor Edward Glaeser, people constantly make choices that decrease their happiness, because they have also more important aims. Therefore, the government should not decrease the alternatives available for the citizen by patronizing them but let the citizen keep a maximal freedom of choice.[78]

It has been argued that happiness at work is one of the driving forces behind positive outcomes at work, rather than just being a resultant product.[79]

Measures

Several scales have been used to measure happiness:

- The Subjective Happiness Scale (SHS) is a four-item scale, measuring global subjective happiness. The scale requires participants to use absolute ratings to characterize themselves as happy or unhappy individuals, as well as it asks to what extent they identify themselves with descriptions of happy and unhappy individuals.[80][81]

- The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) is used to detect the relation between personality traits and positive or negative affects at this moment, today, the past few days, the past week, the past few weeks, the past year, and generally (on average). PANAS is a 20-item questionnaire, which uses a five-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely).[82][83] A longer version with additional affect scales is available in a manual.[84]

- The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) is a global cognitive assessment of life satisfaction developed by Ed Diener. The SWLS requires a person to use a seven-item scale to state their agreement or disagreement (1 = strongly disagree, 4 = neither agree nor disagree, 7 = strongly agree) with five statements about their life.[85][86]

The UK began to measure national well being in 2012,[87] following Bhutan which already measured gross national happiness.

Physical mechanisms

A correlation has been found between hormone levels and happiness. SSRIs, such as Prozac, are used to adjust the levels of seratonin in the clinically unhappy. Researchers, such as Alexander, have indicated that many peoples usage of narcotics may be the unwitting result of attempts to readjust hormone levels to cope with situations that make them unhappy.[88]

Correlation of precuneus gray matter volume, meditation and subjective happiness score

A positive relationship has been found between the volume of gray matter in the right precuneus area of the brain and the subject's subjective happiness score.[89] Interestingly meditation, including mindfulness, based interventions have been found to correlate with a significant gray matter increase within the precuneus.[90][91][92][93][94]

A study on Brahma Kumaris Raja yoga meditators showed them having higher happiness (Oxford happiness questionnaire) than the control group.[95]

Health

In 2005 a study conducted by Andrew Steptow and Michael Marmot at University College London, found that happiness is related to biological markers that play an important role in health.[96] The researchers aimed to analyze whether there was any association between well-being and three biological markers: heart rate, cortisol levels, and plasma fibrinogen levels. Interestingly, the participants who rated themselves the least happy had cortisol levels that were 48% higher than those who rated themselves as the most happy. The least happy subjects also had a large plasma fibrinogen response to two stress-inducing tasks: the Stroop test, and tracing a star seen in a mirror image. Repeating their studies three years later Steptow and Marmot found that participants who scored high in positive emotion continued to have lower levels of cortisol and fibrinogen, as well as a lower heart rate.

In Happy People Live Longer (2011),[97] Bruno Frey reported that happy people live 14% longer, increasing longevity 7.5 to 10 years and Richard Davidson's bestseller (2012) The Emotional Life of Your Brain argues that positive emotion and happiness benefit long-term health.

However, in 2015 a study building on earlier research found that happiness has no effect on mortality.[98] "This "basic belief that if you're happier you're going to live longer. That's just not true."[99] Consistent results are that "apart from good health, happy people were more likely to be older, not smoke, have fewer educational qualifications, do strenuous exercise, live with a partner, do religious or group activities and sleep for eight hours a night."[99]

Happiness does however seem to have a protective impact on immunity. The tendency to experience positive emotions was associated with greater resistance to colds and flu in interventional studies irrespective of other factors such as smoking, drinking, exercise, and sleep.[100][101]

At work

Despite a large body of positive psychological research into the relationship between happiness and productivity,[102][103][104] happiness at work has traditionally been seen as a potential by-product of positive outcomes at work, rather than a pathway to success in business. However a growing number of scholars, including Boehm and Lyubomirsky, argue that it should be viewed as one of the major sources of positive outcomes in the workplace.[79][105]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Happiness. |

References

- ↑ "happiness". Wolfram Alpha.

- ↑ Anand, P (2016). Happiness Explained. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ McMahon, Darrin M. (2004). "From the happiness of virtue to the virtue of happiness: 400 B.C. – A.D. 1780". Daedalus. 133 (2): 5–17. doi:10.1162/001152604323049343. JSTOR 20027908.

- ↑ Schlesinger, Arthur M. (1964). "The Lost Meaning of "The Pursuit of Happiness"". The William and Mary Quarterly. 21 (3): 325–7. doi:10.2307/1918449. JSTOR 1918449.

- ↑ Two American Dreams: how a dumbed-down nation lost sight of a great idea, the Guardian

- ↑ Graham, Michael C. (2014). Facts of Life: ten issues of contentment. Outskirts Press. pp. 6–10. ISBN 978-1-4787-2259-5.

- ↑ Deci, Edward L.; Ryan, Richard M. (2006). "Hedonia, eudaimonia, and well-being: an introduction". Journal of Happiness Studies. 9 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

- ↑ Helliwell, John; Layard, Richard; Sachs, Jeffrey, eds. (2012). World Happiness Report 2012. ISBN 978-0-9968513-0-5.

- ↑ Wallis, Claudia (2005-01-09). "Science of Happiness: New Research on Mood, Satisfaction". TIME. Archived from the original on November 15, 2010. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- ↑ Happiness being partly in our genes

- ↑ Meike Bartels confirming genetic basis for happiness

- ↑ Scott Stossel. "What Makes Us Happy, Revisited - Scott Stossel". The Atlantic. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Algoe, Sara B.; Haidt, Jonathan (2009). "Witnessing excellence in action: the 'other-praising' emotions of elevation, gratitude, and admiration". The Journal of Positive Psychology. 4 (2): 105–127. doi:10.1080/17439760802650519. PMC 2689844

. PMID 19495425.

. PMID 19495425. - ↑ Boston.com, August 23, 2009

- ↑ Van der Merwe, Paul (2016). Lucky Go Happy : Make Happiness Happen!. South Africa: Reach Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 9781496941640.

- ↑ Dunn, E. W.; Aknin, L. B.; Norton, M. I. (2008). "Spending Money on Others Promotes Happiness". Science. 319 (5870): 1687–8. Bibcode:2008Sci...319.1687D. doi:10.1126/science.1150952. PMID 18356530..

- ↑ Claire Bates (2012-10-31). "Is this the world's happiest man? Brain scans reveal French monk found to have 'abnormally large capacity' for joy, and it could be down to meditation". Mail Online. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Seligman, Martin E. P. (2004). "Can happiness be taught?". Daedalus. 133 (2): 80–87. doi:10.1162/001152604323049424. JSTOR 20027916.

- ↑ 2009 article in Frontiers in Evolutionary Neuroscience

- ↑ Rooney, Ciara; McKinley, Michelle C.; Woodside, Jayne V. (2013). "The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: a review of the literature and future directions". Proceedings of the Nutrition Society. 72 (4): 420–32. doi:10.1017/S0029665113003388. PMID 24020691.

- ↑ Kye, Su Yeon; Park, Keeho (2014). "Health-related determinants of happiness in Korean adults". International Journal of Public Health. 59 (5): 731–8. doi:10.1007/s00038-014-0588-0. PMID 25033934.

- ↑ Fararouei, M.; Brown, I.J.; Akbartabar Toori, M.; Estakhrian Haghighi, R.; Jafari, J. (2013). "Happiness and health behaviour in Iranian adolescent girls". Journal of Adolescence. 36 (6): 1187–92. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.09.006. PMID 24215965.

- ↑ Piqueras, José A; Kuhne, Walter; Vera-Villarroel, Pablo; van Straten, Annemieke; Cuijpers, Pim (2011). "Happiness and health behaviours in Chilean college students: A cross-sectional survey". BMC Public Health. 11: 443. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-11-443. PMC 3125376

. PMID 21649907.

. PMID 21649907. - ↑ Boehm, Julia K.; Williams, David R.; Rimm, Eric B.; Ryff, Carol; Kubzansky, Laura D. (2013). "Association Between Optimism and Serum Antioxidants in the Midlife in the United States Study". Psychosomatic Medicine. 75 (1): 2–10. doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e31827c08a9. PMC 3539819

. PMID 23257932.

. PMID 23257932. - ↑ Blanchflower, David G.; Oswald, Andrew J.; Stewart-Brown, Sarah (2012). "Is Psychological Well-Being Linked to the Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables?". Social Indicators Research. 114 (3): 785–801. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0173-y.

- ↑ Routledge, Clay (2012). "Are Religious People Happier Than Non-religious People?". Psychology Today. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

- ↑ Tahor, Grundtvig (2011-04-01). "Praying for Dopamine" (PDF). Lab Times. p. 12. Retrieved 2014-01-24.

Religious prayer is a form of frequently recurring behaviour capable of stimulating the dopaminergic reward system in practicing individuals

- ↑ Baetz, Marilyn; Toews, John (2009). "Clinical implications of research on religion, spirituality, and mental health". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 54 (5): 292–301. PMID 19497161.

- ↑ Ellison, Christopher G.; George, Linda K. (1994). "Religious Involvement, Social Ties, and Social Support in a Southeastern Community". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 33 (1): 46–61. doi:10.2307/1386636. JSTOR 1386636.

- ↑ McCullough, Michael E; Larson, David B (1999). "Religion and depression: a review of the literature". Twin Research. 2 (2): 126–36. doi:10.1375/136905299320565997. PMID 10480747.

- ↑ Strawbridge, William J.; Shema, Sarah J.; Cohen, Richard D.; Kaplan, George A. (2001). "Religious attendance increases survival by improving and maintaining good health behaviors, mental health, and social relationships". Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 23 (1): 68–74. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2301_10. PMID 11302358.

- ↑ Burris, C.T. (1999). "Religious Orientation Scale". In Hill, Peter C.; Hood, Ralph W. Measures of Religiosity. Birmingham: Religious Education Press. pp. 144–53. ISBN 978-0-89135-106-1.

- ↑ Paul, Pamela (2005-01-09). "The New Science of Happiness". Time.

- ↑ Koenig. Harold G., Larson, David B., and Mcculloug, Michael E. –Handbook of Religion and Health (see article), p.122, Oxford University Press (2001), ISBN 0-8133-6719-0

Feigelman et al. (1992) examined happiness in Americans who have given up religion. Using pooled data from the General Social Surveys conducted between 1972 and 1990, investigators identified more than 20,000 adults for their study. Subjects of particular interest were “disaffiliates”—those who were affiliated with a religion at age 16 but who were not affiliated at the time of the survey (disaffiliates comprised from 4.4% to 6.0% of respondents per year during the 18 years of surveys). “Actives” were defined as persons who reported a religious affiliation at age 16 and a religious affiliation at the time of the survey (these ranged from 84.7% to 79.5% of respondents per year between 1972 and 1990). Happiness was measured by a single question that assessed general happiness (very happy, pretty happy, not too happy). When disaffiliates (n = 1,420) were compared with actives (n = 21,052), 23.9% of disaffiliates indicated they were “very happy, ” as did 34.2% of actives. When the analysis was stratified by marital status, the likelihood of being very happy was about 25% lower (i.e., 10% difference) for married religious disaffiliates compared with married actives. Multiple regression analysis revealed that religious disaffiliation explained only 2% of the variance in overall happiness, after marital status and other covariates were controlled. Investigators concluded that there was little relationship between religious disaffiliation and unhappiness (quality rating 7) - ↑ Koenig. Harold G., Larson, David B., and Mcculloug, Michael E. –Handbook of Religion and Health(see article), p.111, Oxford University Press (2001)

Currently, approximately 8% of the U.S. population claim no religious affiliation (Kosmin & Lachman, 1993). People with no affiliation appear to be at greater risk for depressive symptoms than those affiliated with a religion. In a sample of 850 medically ill men, Koenig, Cohen, Blazer, Pieper, et al. (1992) examined whether religious affiliation predicted depression after demographics, medical status, and a measure of religious coping were controlled. They found that, when relevant covariates were controlled, men who indicated that they had “no religious affiliation” had higher scores on the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (an observer-administered rating scale) than did men who identified themselves as moderate Protestants, Catholics, or nontraditional Christians. - 1 2 Smith, Timothy B.; McCullough, Michael E.; Poll, Justin (2003). "Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events". Psychological Bulletin. 129 (4): 614–36. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614. PMID 12848223.

- ↑ The 2008 Legatum Prosperity Index, Summary p.40.

Research suggests that religious people's happiness is less vulnerable to fluctuations in economic and political uncertainty, personal unemployment and income changes. The Prosperity Index identifies similar effects at the country level, with a number of highly religious countries reporting higher levels of happiness than might be expected based on the standard of living alone: this effect is most pronounced in Mexico, El Salvador, the Dominican republic, Indonesia, Venezuela and Nigeria. - ↑ Is Religion Dangerous?p156, citing David Myers The Science of Subjective Well-Being Guilford Press 2007

- ↑ Is Religion Dangerous? cites similar results from theHandbook of Religion and Mental Health Harold Koenig (ed.) ISBN 978-0-12-417645-4

- ↑ Hackney, Charles H.; Sanders, Glenn S. (2003). "Religiosity and Mental Health: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Studies". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 42 (1): 43–55. doi:10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160.

- ↑ Moreira-Almeida, Alexander; Lotufo Neto, Francisco; Koenig, Harold G (2006). "Religiousness and mental health: a review". Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 28 (3): 242–50. doi:10.1590/S1516-44462006005000006. PMID 16924349.

- ↑ Robert D. Putnam makes this argument in his book (with David Campell) American Grace (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2012).

- ↑ Vail, K. E.; Rothschild, Z. K.; Weise, D. R.; Solomon, S.; Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J. (2010). "A Terror Management Analysis of the Psychological Functions of Religion". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 14 (1): 84–94. doi:10.1177/1088868309351165. PMID 19940284.

- ↑ Fletcher. "Reasonable Doubts: Episode 81 Sacrificial Lambs". doubtreligion.blogspot.com.

- ↑ Silton, Nava R.; Flannelly, Kevin J.; Galek, Kathleen; Ellison, Christopher G. (2014). "Beliefs About God and Mental Health Among American Adults". Journal of Religion and Health. 53 (5): 1285–96. doi:10.1007/s10943-013-9712-3. PMID 23572240.

- ↑ Religiosity Highest in World's Poorest Nations, Gallup Global Reports, August 31, 2010.

- ↑ Religion Provides Emotional Boost to World’s Poor, Gallup Global Reports, March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Luke Galen Center Stage Podcast, Episode 104 - Profiles of the Godless: Results from the Non-Religious Identification Survey.

- ↑ Galen, Luke W.; Kloet, Jim (2011). "Personality and Social Integration Factors Distinguishing Nonreligious from Religious Groups: The Importance of Controlling for Attendance and Demographics". Archive for the Psychology of Religion. 33 (2): 205–28. doi:10.1163/157361211X570047.

- ↑ Jeremy. "Reasonable Doubts: RD Extra: Denying Death". doubtreligion.blogspot.com.

- ↑ "In Buddhism, There Are Seven Factors of Enlightenment. What Are They?". About.com Religion & Spirituality. Retrieved 2016-03-26.

- ↑ "Buddhist studies for primary and secondary students, Unit Six: The Four Immeasurables". Buddhanet.net. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Bhikkhu, Thanissaro (1999). "A Guided Meditation".

- ↑ Yanklowitz, Shmuly. "Judaism's value of happiness living with gratitude and idealism." Bloggish. The Jewish Journal. March 9, 2012.

- ↑ Breslov.org. Archived November 12, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Accessed November 11, 2014.

- ↑ Aquinas, Thomas. "Question 3. What is happiness". Summa Theologiae. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007.

- ↑ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Happiness". newadvent.org.

- ↑ Holder, Mark D.; Coleman, Ben; Wallace, Judi M. (2008). "Spirituality, Religiousness, and Happiness in Children Aged 8–12 Years". Journal of Happiness Studies. 11 (2): 131–50. doi:10.1007/s10902-008-9126-1.

- ↑ Chan, Wing-tsit (1963). A Source Book in Chinese Philosophy. Princeton, NJ, US: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01964-9.

- ↑ Levine, Marvin (2000). The Positive Psychology of Buddhism and Yoga : Paths to a Mature Happiness. Lawrence Erlbaum. ISBN 0-8058-3833-3.

- ↑ Eudaimonia (Greek: εὐδαιμονία) is a classical Greek word commonly translated as 'happiness' or, better yet, 'flourishing'. Etymologically, it consists of the word "eu" ("good" or "well being") and "daimōn" ("spirit" or "minor deity", used by extension to mean one's lot or fortune).

- ↑ "Nietzsche's Moral and Political Philosophy". stanford.edu.

- ↑ "Friedrich Nietzsche (1844—1900)". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- ↑ "SUMMA THEOLOGICA: Man's last end (Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 1)". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ "SUMMA THEOLOGICA: Secunda Secundae Partis". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ "SUMMA THEOLOGICA: What is happiness (Prima Secundae Partis, Q. 3)". Newadvent.org. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Frey, Bruno S.; Alois Stutzer (December 2001). Happiness and Economics. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-06998-0.

- ↑ "In Pursuit of Happiness Research. Is It Reliable? What Does It Imply for Policy?". The Cato institute. 2007-04-11.

- ↑ "Wealth and happiness revisited Growing wealth of nations does go with greater happiness" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Leonhardt, David (2008-04-16). "Maybe Money Does Buy Happiness After All". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-04-10.

- ↑ "Economic Growth and Subjective Well-Being: Reassessing the Easterlin Paradox" (PDF). bpp.wharton.upenn.edu. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 17, 2012.

- ↑ "Boston.com". Boston.com. 2008-11-23. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ In Pursuit of Happiness Research. Is It Reliable? What Does It Imply for Policy? The Cato institute. April 11, 2007

- ↑ The Scientist's Pursuit of Happiness Archived February 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., Policy, Spring 2005.

- ↑ Radcliff, Benjamin (2013) The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press). See also this collection of full-text peer reviewed scholarly articles on this subject by Radcliff and colleagues (from "Social Forces," "The Journal of Politics," and "Perspectives on Politics," among others)

- ↑ Michael Krassa (14 May 2014). "Does a higher minimum wage make people happier?". Washington Post.

- ↑ Weiner, Eric J. (2007-11-13). "Four months of boom, bust, and fleeing foreign credit". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 22, 2007.

- ↑ Coercive regulation and the balance of freedom, Edward Glaeser, Cato Unbound 11.5.2007

- 1 2 Boehm, J. K.; Lyubomirsky, S. (2008). "Does Happiness Promote Career Success?". Journal of Career Assessment. 16 (1): 101–16. doi:10.1177/1069072707308140.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 22, 2012. Retrieved April 1, 2012.

- ↑ Lyubomirsky, Sonja; Lepper, Heidi S. (February 1999). "A Measure of Subjective Happiness: Preliminary Reliability and Construct Validation". Social Indicators Research. 46 (2): 137–55. doi:10.1023/A:1006824100041. JSTOR 27522363.

- ↑ Search | Rutgers University-Camden

- ↑ Watson, David; Clark, Lee A.; Tellegen, Auke (1988). "Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 54 (6): 1063–70. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. PMID 3397865.

- ↑ Watson, David; Clark, Lee Anna (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule - Expanded Form. The University of Iowa.

- ↑ "SWLS Rating Form". tbims.org.

- ↑ Diener, Ed; Emmons, Robert A.; Larsen, Randy J.; Griffin, Sharon (1985). "The Satisfaction With Life Scale". Journal of Personality Assessment. 49 (1): 71–5. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13. PMID 16367493.

- ↑ "Measuring National Well-being: Life in the UK, 2012". Ons.gov.uk. 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Alexander, Bruce K. (1981). "Rat Park". Psychopharmacology.

- ↑ Sato, Wataru; Kochiyama, Takanori; Uono, Shota; Kubota, Yasutaka; Sawada, Reiko; Yoshimura, Sayaka; Toichi, Motomi (2015). "The structural neural substrate of subjective happiness". Scientific Reports. 5: 16891. Bibcode:2015NatSR...516891S. doi:10.1038/srep16891. PMC 4653620

. PMID 26586449.

. PMID 26586449. - ↑ Black, David S.; Kurth, Florian; Luders, Eileen; Wu, Brian (2014). "Brain Gray Matter Changes Associated with Mindfulness Meditation in Older Adults: An Exploratory Pilot Study using Voxelbased Morphometry". Neuro. 1 (1): 23–26. doi:10.17140/NOJ-1-106. PMC 4306280

. PMID 25632405.

. PMID 25632405. - ↑ Hölzel, Britta K.; Carmody, James; Vangel, Mark; Congleton, Christina; Yerramsetti, Sita M.; Gard, Tim; Lazar, Sara W. (2011). "Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density". Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 191 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006. PMC 3004979

. PMID 21071182.

. PMID 21071182. - ↑ Kurth, Florian; MacKenzie-Graham, Allan; Toga, Arthur W.; Luders, Eileen (2015). "Shifting brain asymmetry: the link between meditation and structural lateralization". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 10 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1093/scan/nsu029. PMID 24643652.

- ↑ Fox, Kieran C.R.; Nijeboer, Savannah; Dixon, Matthew L.; Floman, James L.; Ellamil, Melissa; Rumak, Samuel P.; Sedlmeier, Peter; Christoff, Kalina (2014). "Is meditation associated with altered brain structure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of morphometric neuroimaging in meditation practitioners". Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 43: 48–73. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.03.016. PMID 24705269.

- ↑ Hölzel, Britta K.; Carmody, James; Evans, Karleyton C.; Hoge, Elizabeth A.; Dusek, Jeffery A.; Morgan, Lucas; Pitman, Roger K.; Lazar, Sara W. (2010). "Stress reduction correlates with structural changes in the amygdala". Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience. 5 (1): 11–7. doi:10.1093/scan/nsp034. PMC 2840837

. PMID 19776221.

. PMID 19776221. - ↑ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3843423

- ↑ Steptoe, A.; Wardle, J.; Marmot, M. (2005). "Positive affect and health-related neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and inflammatory processes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 102 (18): 6508–12. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.6508S. doi:10.1073/pnas.0409174102. PMC 1088362

. PMID 15840727.

. PMID 15840727. - ↑ Frey, B. S. (2011). "Happy People Live Longer". Science. 331 (6017): 542–3. Bibcode:2011Sci...331..542F. doi:10.1126/science.1201060. PMID 21292959.

- ↑ Liu, Bette; Floud, Sarah; Pirie, Kirstin; Green, Jane; Peto, Richard; Beral, Valerie (2016). "Does happiness itself directly affect mortality? The prospective UK Million Women Study". The Lancet. 387 (10021): 874–81. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01087-9. PMID 26684609.

- 1 2 Alexander, Harriet (13 December 2015). "UNSW research finds happy people do not live longer when ill health is removed from equation". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 15 December 2015.

- ↑ Cohen, Sheldon; Doyle, William J.; Turner, Ronald B.; Alper, Cuneyt M.; Skoner, David P. (2003). "Emotional Style and Susceptibility to the Common Cold". Psychosomatic Medicine. 65 (4): 652–7. doi:10.1097/01.PSY.0000077508.57784.DA. PMID 12883117.

- ↑ Cohen, Sheldon; Alper, Cuneyt M.; Doyle, William J.; Treanor, John J.; Turner, Ronald B. (2006). "Positive Emotional Style Predicts Resistance to Illness After Experimental Exposure to Rhinovirus or Influenza A Virus". Psychosomatic Medicine. 68 (6): 809–15. doi:10.1097/01.psy.0000245867.92364.3c. PMID 17101814.

- ↑ Carr, A.: "Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Human Strengths" Hove, Brunner-Routledge 2004

- ↑ Isen, A. (2000). "Positive Affect and Decision-making". In Lewis, Michael; Haviland-Jones, Jeannette M. Handbook of Emotions (2nd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. pp. 417–36. ISBN 978-1-57230-529-8.

- ↑ Buss, David M. (2000). "The evolution of happiness". American Psychologist. 55 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.15. PMID 11392858.

- ↑ Lyubomirsky, Sonja; King, Laura; Diener, Ed (2005). "The Benefits of Frequent Positive Affect: Does Happiness Lead to Success?". Psychological Bulletin. 131 (6): 803–55. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803. PMID 16351326.

Further reading

- Books

- Van der Merwe, Paul, Lucky Go Happy : Make Happiness Happen!, Reach Publishers, 2016. ISBN 9781496941640

- Anand Paul "Happiness Explained: What Human Flourishing Is and What We Can Do to Promote It", Oxford, Oxford University Press 2016. ISBN 0198735456

- Michael Argyle "The psychology of happiness", 1987

- Boehm, J K. & S. Lyubomirsky, Journal of Career Assessment. Vol 16(1), Feb 2008, 101–116.

- Norman M. Bradburn "The structure of psychological well-being", 1969

- C. Robert Cloninger, Feeling Good: The Science of Well-Being, Oxford, 2004.

- Gregg Easterbrook "The progress paradox – how life gets better while people feel worse", 2003

- Michael W. Eysenck "Happiness – facts and myths", 1990

- Daniel Gilbert, Stumbling on Happiness, Knopf, 2006.

- Carol Graham "Happiness Around the World: The Paradox of Happy Peasants and Miserable Millionaires", OUP Oxford, 2009. ISBN 978-0-19-954905-4

- W. Doyle Gentry "Happiness for dummies", 2008

- James Hadley, Happiness: A New Perspective, 2013, ISBN 978-1493545261

- Joop Hartog & Hessel Oosterbeek "Health, wealth and happiness", 1997

- Hills P., Argyle M. (2002). "The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: a compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences". Psychological Wellbeing. 33: 1073–1082. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(01)00213-6.

- Robert Holden "Happiness now!", 1998

- Barbara Ann Kipfer, 14,000 Things to Be Happy About, Workman, 1990/2007, ISBN 978-0-7611-4721-3.

- Neil Kaufman "Happiness is a choice", 1991

- Stefan Klein, The Science of Happiness, Marlowe, 2006, ISBN 1-56924-328-X.

- Koenig HG, McCullough M, & Larson DB. Handbook of religion and health: a century of research reviewed (see article). New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

- McMahon, Darrin M., Happiness: A History, Atlantic Monthly Press, November 28, 2005. ISBN 0-87113-886-7

- McMahon, Darrin M., The History of Happiness: 400 B.C. – A.D. 1780, Daedalus journal, Spring 2004.

- Richard Layard, Happiness: Lessons From A New Science, Penguin, 2005, ISBN 978-0-14-101690-0.

- Luskin, Frederic, Kenneth R. Pelletier, Dr. Andrew Weil (Foreword). "Stress Free for Good: 10 Scientifically Proven Life Skills for Health and Happiness." 2005

- James Mackaye "Economy of happiness", 1906

- Desmond Morris "The nature of happiness", 2004

- David G. Myers, Ph. D., The Pursuit of Happiness: Who is Happy—and Why, William Morrow and Co., 1992, ISBN 0-688-10550-5.

- Niek Persoon "Happiness doesn't just happen", 2006

- Benjamin Radcliff The Political Economy of Human Happiness (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013).

- Ben Renshaw "The secrets of happiness", 2003

- Fiona Robards, "What makes you happy?" Exisle Publishing, 2014, ISBN 978-1-921966-31-6

- Bertrand Russell "The conquest of happiness", orig. 1930 (many reprints)

- Martin E.P. Seligman, Authentic Happiness, Free Press, 2002, ISBN 0-7432-2298-9.

- Alexandra Stoddard "Choosing happiness – keys to a joyful life", 2002

- Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Analysis of Happiness, The Hague, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1976

- Elizabeth Telfer "Happiness : an examination of a hedonistic and a eudaemonistic concept of happiness and of the relations between them...", 1980

- Ruut Veenhoven "Bibliography of happiness – world database of happiness : 2472 studies on subjective appreciation of life", 1993

- Ruut Veenhoven "Conditions of happiness", 1984

- Joachim Weimann, Andreas Knabe, and Ronnie Schob, eds. Measuring Happiness: The Economics of Well-Being (MIT Press; 2015) 206 pages

- Eric G. Wilson "Against Happiness", 2008

- Articles and videos

- Journal of happiness studies: an interdisciplinary forum on subjective well-being, International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies (ISQOLS), quarterly since 2000, also online

- A Point of View: The pursuit of happiness (January 2015), BBC News Magazine

- Srikumar Rao: Plug into your hard-wired happiness – Video of a short lecture on how to be happy

- Dan Gilbert: Why are we happy? – Video of a short lecture on how our "psychological immune system" lets us feel happy even when things don’t go as planned.

- TED Radio Hour: Simply Happy - various guest speakers, with some research results

External links

- History of Happiness – concise survey of influential theories

- The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry "Pleasure" – ancient and modern philosophers' and neuroscientists' approaches to happiness

- The World Happiness Forum promotes dialogue on tools and techniques for human happiness and wellbeing.

- Action For Happiness is a UK movement committed to building a happier society

- Improving happiness through humanistic leadership- University of Bath, U.K.

- The World Database of Happiness – a register of scientific research on the subjective appreciation of life.

- Oxford Happiness Questionnaire – Online psychological test to measure your happiness.

- Track Your Happiness - research project with downloadable app that surveys users periodically and determines personal factors

- Pharrell Williams - Happy (Official Music Video) added to YouTube by P. Williams: i Am Other - Retrieved 2015-11-21