Hubris

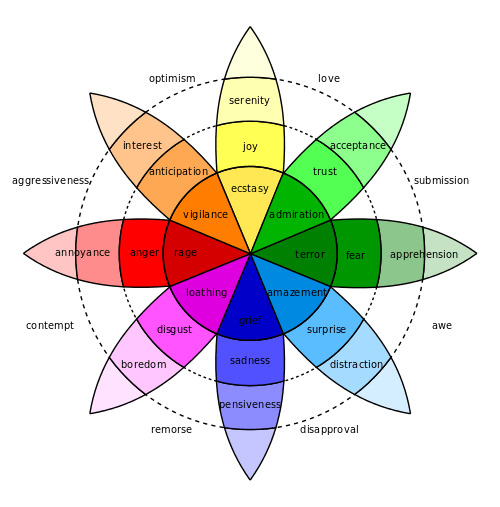

Hubris (/ˈhjuːbrɪs/, also hybris, from ancient Greek ὕβρις) describes a personality quality of extreme or foolish pride or dangerous over-confidence.[1] In its ancient Greek context, it typically describes behavior that defies the norms of behavior or challenges the gods, and which in turn brings about the downfall, or nemesis, of the perpetrator of hubris.

The adjectival form of the noun hubris is "hubristic". Hubris is usually perceived as a characteristic of an individual rather than a group, although the group the offender belongs to may unintentionally suffer consequences from the wrongful act. Hubris often indicates a loss of contact with reality and an overestimation of one's own competence, accomplishments or capabilities. Contrary to common expectations, hubris is not necessarily associated with high self-esteem but with highly fluctuating or variable self-esteem, and a gap between inflated self perception and a more modest reality.

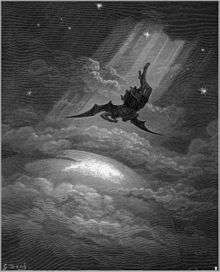

Hubris is generally considered a sin in world religions. C. S. Lewis writes, in Mere Christianity, that pride is the "anti-God" state, the position in which the ego and the self are directly opposed to God: "Unchastity, anger, greed, drunkenness, and all that, are mere fleabites in comparison: it was through Pride that the devil became the devil: Pride leads to every other vice: it is the complete anti-God state of mind."[2]

Ancient Greek origin

In ancient Greek, hubris referred to actions that shamed and humiliated the victim for the pleasure or gratification of the abuser.[3] The term had a strong sexual connotation, and the shame reflected on the perpetrator as well.[4]

Violations of the law against hubris included what might today be termed assault and battery; sexual crimes; or the theft of public or sacred property. Two well-known cases are found in the speeches of Demosthenes, a prominent statesman and orator in ancient Greece. These two examples occurred when first Midias punched Demosthenes in the face in the theatre (Against Midias), and second when (in Against Conon) a defendant allegedly assaulted a man and crowed over the victim. Yet another example of hubris appears in Aeschines' Against Timarchus, where the defendant, Timarchus, is accused of breaking the law of hubris by submitting himself to prostitution and anal intercourse. Aeschines brought this suit against Timarchus to bar him from the rights of political office and his case succeeded.[5]

In Ancient Athens, hubris was defined as the use of violence to shame the victim (this sense of hubris could also characterize rape[6]). Aristotle defined hubris as shaming the victim, not because of anything that happened to the committer or might happen to the committer, but merely for that committer's own gratification:

to cause shame to the victim, not in order that anything may happen to you, nor because anything has happened to you, but merely for your own gratification. Hubris is not the requital of past injuries; this is revenge. As for the pleasure in hubris, its cause is this: naive men think that by ill-treating others they make their own superiority the greater.[7][8][9]

Crucial to this definition are the ancient Greek concepts of honour (τιμή, timē) and shame (αἰδώς, aidōs). The concept of honour included not only the exaltation of the one receiving honour, but also the shaming of the one overcome by the act of hubris. This concept of honour is akin to a zero-sum game. Rush Rehm simplifies this definition of hubris to the contemporary concept of "insolence, contempt, and excessive violence".

In Greek mythology, when a figure's hubris offends the pagan gods of ancient Greece, it is usually punished; examples of such hubristic, sinful humans include Icarus, Phaethon, Arachne, Salmoneus, Niobe, Cassiopeia, and Tereus.

Modern usage

In its modern usage, hubris denotes overconfident pride and arrogance. Hubris is often associated with a lack of humility. Sometimes a person's hubris is also associated with a lack of knowledge.The accusation of hubris often implies that suffering or punishment will follow, similar to the occasional pairing of hubris and nemesis in Greek mythology. The proverb "pride goeth (goes) before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall" (from the biblical Book of Proverbs, 16:18) is thought to sum up the modern use of hubris. Hubris is also referred to as "pride that blinds," as it often causes a committer of hubris to act in foolish ways that belie common sense.[10] In other words, the modern definition may be thought of as, "that pride that goes just before the fall."

Examples of hubris are often found in literature, most famously in Paradise Lost: John Milton's depiction of Lucifer (who attempts to force the other angels to worship him, is cast down to hell by God and the innocent angels, and proclaims: "Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven.") Victor in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein manifests hubris in his attempt to become a great scientist by creating life through technological means, but eventually regrets this previous desire. Marlowe's play Doctor Faustus portrays the eponymous character as a scholar whose arrogance and pride compel him to sign a deal with the Devil, and retain his haughtiness until his death and damnation, despite the fact that he could easily have repented had he chosen to do so. Chinua Achebe's novel Things Fall Apart has been called a modern Greek tragedy, and the main character Okonkwo is a classic tragic hero whose hubris leads to his downfall. Another example is the character Walter White from the TV show Breaking Bad, whose entry into the criminal world gradually caused him to eradicate all moral boundaries (except for the will to protect his family) and perform heinous crimes in order to empower his ever growing meth empire. The characters Pride and Father in the popular manga Fullmetal Alchemist were inspired by the sin of hubris.

One notable example is the Battle of Little Big Horn, as General George Armstrong Custer was apocryphally reputed to have said there: "Where did all those damned Indians come from?"[11]

More recently, in his two-volume biography of Adolf Hitler, historian Ian Kershaw uses both 'hubris' and 'nemesis' as titles. The first volume, Hubris,[12] describes Hitler's early life and rise to political power. The second, Nemesis,[13] gives details of Hitler's role in the Second World War, and concludes with his fall and suicide in 1945.

See also

References

- ↑ "Definition of HUBRIS". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2016-04-22.

- ↑ Lewis, C.S. (2001). Mere Christianity : a revised and amplified edition, with a new introduction, of the three books, Broadcast talks, Christian behaviour, and Beyond personality. San Francisco: Harper. ISBN 978-0-06-065292-0.

- ↑ David Cohen, "Law, society and homosexuality or hermaphrodity in Classical Athens" in Studies in ancient Greek and Roman society By Robin Osborne; p 64

- ↑ Cartledge; Paul Millett (2003). Nomos: Essays in Athenian Law, Politics and Society. Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-521-52209-0. Retrieved 2011-11-14.

- ↑ Aeschines "Against Timarchus" from Thomas K. Hubbard's Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: A Sourcebook of Basic Documents

- ↑ "Hubris". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 April 2016.

- ↑ Aristotle, Rhetoric 1378b.

- ↑ Cohen, David (1995). Law, Violence, and Community in Classical Athens. Cambridge University Press. p. 145. ISBN 0521388376. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ Ludwig, Paul W. (2002). Eros and Polis: Desire and Community in Greek Political Theory. Cambridge University Press. p. 178. ISBN 1139434179. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- ↑ "The 1920 Farrow's Bank Failure: A Case of Managerial Hubris". Durham University. Retrieved October 1, 2014.

- ↑ Morson, Gary Saul (June 28, 2011). The Words of Others: From Quotations to Culture. New Haven. Connecticut: Yale University Press. p. 176. ISBN 9780300167474. Retrieved March 5, 2016. “Proving that it is better to be mustered out of the militia than it is to be custered out of the cavalry.”

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (1998). Hitler 1889–1936: Hubris. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04671-7. OCLC 50149322.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian (2000). Hitler 1936–1945: Nemesis. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04994-7. OCLC 45234118.

Further reading

- Cairns, Douglas L. (1996). "Hybris, Dishonour, and Thinking Big". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 116: 1–32. doi:10.2307/631953.

- Fisher, Nick (1992). Hybris: a study in the values of honour and shame in Ancient Greece. Warminster, UK: Aris & Phillips. A book-length discussion of the meaning and implications of hybristic behavior in ancient Greece.

- MacDowell, Douglas (1976). "Hybris in Athens". Greece and Rome. 23 (1): 14–31. doi:10.1017/S0017383500018210.

- Michael DeWilde, The Psychological and Spiritual Roots of a Universal Affliction

- Hubris on 2012's Encyclopædia Britannica

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

| Look up hubris in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |