Sanskrit

| Sanskrit | |

|---|---|

| saṃskṛtam | |

|

The word saṃskṛtam written in Devanagari. | |

| Pronunciation | [sə̃skr̩t̪əm] |

| Region | Greater India |

| Era |

ca. 2nd millennium BCE–600 BCE (Vedic Sanskrit[1]), after which it gave rise to the Middle Indo-Aryan languages. Continues as a liturgical language (Classical Sanskrit). |

| Revival | Attempts at revitalization. 14,346 self-reported speakers (2001 census)[2] |

|

Indo-European

| |

Early forms |

Vedic Sanskrit

|

| No native script. Written in various Brahmic scripts.[3] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | India |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

sa |

| ISO 639-2 |

san |

| ISO 639-3 |

san |

| Glottolog |

sans1269[4] |

Sanskrit (/ˈsænskrɪt/; Sanskrit: saṃskṛtam [sə̃skr̩t̪əm][lower-alpha 1] or saṃskṛta, originally saṃskṛtā vāk, "refined speech") is the primary sacred language of Hinduism and Mahāyāna Buddhism, a philosophical language in Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism, and a literary language that was in use as a lingua franca in Greater India. It is a standardised dialect of Old Indo-Aryan, originating as Vedic Sanskrit and tracing its linguistic ancestry back to Proto-Indo-Iranian and Proto-Indo-European.[5] Today it is listed as one of the 22 scheduled languages of India[6] and is an official language of the state of Uttarakhand.[7] As one of the oldest Indo-European languages for which substantial written documentation exists, Sanskrit holds a prominent position in Indo-European studies.[8][9]

The body of Sanskrit literature encompasses a rich tradition of poetry and drama as well as scientific, technical, philosophical and religious texts.[10][11] Sanskrit continues to be widely used as a ceremonial language in Hindu religious rituals and Buddhist practice in the form of hymns and chants. Spoken Sanskrit has been revived in some villages with traditional institutions, and there are attempts to enhance its popularity.

Name

The Sanskrit verbal adjective sáṃskṛta- may be translated as "put together, constructed, well or completely formed; refined, adorned, highly elaborated". It is derived from the root word saṃ-skar- "to put together, compose, arrange, prepare"[12]

As a term for "refined or elaborated speech" the adjective appears only in Epic and Classical Sanskrit in the Manusmṛti and the Mahabharata. The language referred to as saṃskṛta "the cultured language" has by definition always been a "sacred" and "sophisticated" language, used for religious and learned discourse in ancient India, in contrast to the language spoken by the people, prākṛta- "natural, artless, normal, ordinary".[13]

Variants

The pre-Classical form of Sanskrit is known as Vedic Sanskrit, with the language of the Rigveda being the oldest and most archaic stage preserved, dating back to the early second millennium BCE.[14][15]

Classical Sanskrit is the standard register as laid out in the grammar of Pāṇini, around the fourth century BCE.[16] Its position in the cultures of Greater India is akin to that of Latin and Ancient Greek in Europe and it has significantly influenced most modern languages of the Indian subcontinent, particularly in India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Nepal.[17]

Vedic Sanskrit

Sanskrit, as defined by Pāṇini, evolved out of the earlier Vedic form. The present form of Vedic Sanskrit can be traced back to as early as the second millennium BCE (for Rig-vedic).[14] Scholars often distinguish Vedic Sanskrit and Classical or "Pāṇinian" Sanskrit as separate dialects. Although they are quite similar, they differ in a number of essential points of phonology, vocabulary, grammar and syntax. Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, a large collection of hymns, incantations (Samhitas) and theological and religio-philosophical discussions in the Brahmanas and Upanishads. Modern linguists consider the metrical hymns of the Rigveda Samhita to be the earliest, composed by many authors over several centuries of oral tradition. The end of the Vedic period is marked by the composition of the Upanishads, which form the concluding part of the traditional Vedic corpus; however, the early Sutras are Vedic, too, both in language and content.[18]

Classical Sanskrit

For nearly 2000 years, Sanskrit was the language of a cultural order that exerted influence across South Asia, Inner Asia, Southeast Asia, and to a certain extent East Asia.[19] A significant form of post-Vedic Sanskrit is found in the Sanskrit of Indian epic poetry—the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The deviations from Pāṇini in the epics are generally considered to be on account of interference from Prakrits, or innovations, and not because they are pre-Paninian.[20] Traditional Sanskrit scholars call such deviations ārṣa (आर्ष), meaning 'of the ṛṣis', the traditional title for the ancient authors. In some contexts, there are also more "prakritisms" (borrowings from common speech) than in Classical Sanskrit proper. Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit is a literary language heavily influenced by the Middle Indo-Aryan languages, based on early Buddhist Prakrit texts which subsequently assimilated to the Classical Sanskrit standard in varying degrees.[21]

There were four principal dialects of classical Sanskrit: paścimottarī (Northwestern, also called Northern or Western), madhyadeśī (lit., middle country), pūrvi (Eastern) and dakṣiṇī (Southern, arose in the Classical period). The predecessors of the first three dialects are attested in Vedic Brāhmaṇas, of which the first one was regarded as the purest (Kauṣītaki Brāhmaṇa, 7.6).[22]

Contemporary usage

As a spoken language

In the 2001 census of India, 14,135 people reported Sanskrit as their native language.[2] Since the 1990s, movements to spread spoken Sanskrit have been increasing. Organisations like Samskrita Bharati conduct Speak Sanskrit workshops to popularise the language.

Indian newspapers have published reports about several villages, where, as a result of recent revival attempts, large parts of the population, including children, are learning Sanskrit and are even using it to some extent in everyday communication:

- Mattur, Shimoga district, Karnataka[23]

- Jhiri, Rajgarh district, Madhya Pradesh[24]

- Ganoda, Banswara district, Rajasthan[25]

- Shyamsundarpur, Kendujhar district, Odisha[26]

According to the 2011 national census of Nepal, 1,669 people use Sanskrit as their native language.[27]

In official use

In India, Sanskrit is among the 14 original languages of the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution. The state of Uttarakhand in India has ruled Sanskrit as its second official language. In October 2012 social activist Hemant Goswami filed a writ petition in the Punjab and Haryana High Court for declaring Sanskrit as a 'minority' language.[28][29][30]

Contemporary literature and patronage

More than 3,000 Sanskrit works have been composed since India's independence in 1947.[31] Much of this work has been judged of high quality, in comparison to both classical Sanskrit literature and modern literature in other Indian languages.[32][33]

The Sahitya Akademi has given an award for the best creative work in Sanskrit every year since 1967. In 2009, Satya Vrat Shastri became the first Sanskrit author to win the Jnanpith Award, India's highest literary award.[34]

In music

Sanskrit is used extensively in the Carnatic and Hindustani branches of classical music. Kirtanas, bhajans, stotras, and shlokas of Sanskrit are popular throughout India. The samaveda uses musical notations in several of its recessions.[35]

In Mainland China, musicians such as Sa Dingding have written pop songs in Sanskrit.[36]

In mass media

Over 90 weeklies, fortnightlies and quarterlies are published in Sanskrit. Sudharma, a daily newspaper in Sanskrit, has been published out of Mysore, India, since 1970, while Sanskrit Vartman Patram and Vishwasya Vrittantam started in Gujarat during the last five years.[37] Since 1974, there has been a short daily news broadcast on state-run All India Radio.[37] These broadcasts are also made available on the internet on AIR's website.[38][39] Sanskrit news is broadcast on TV and on the internet through the DD National channel at 6:55 AM IST.[40]

In liturgy

Sanskrit is the sacred language of various Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions. It is used during worship in Hindu temples throughout the world. In Newar Buddhism, it is used in all monasteries, while Mahayana and Tibetan Buddhist religious texts and sutras are in Sanskrit as well as vernacular languages. Jain texts are written in Sanskrit,[41][42] including the Tattvartha sutra, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra , the Bhaktamara Stotra and the Agamas.

It is also popular amongst the many practitioners of yoga in the West, who find the language helpful for understanding texts such as the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali.

Symbolic usage

In Nepal, India and Indonesia, Sanskrit phrases are widely used as mottoes for various national, educational and social organisations:

- India: Satyameva Jayate meaning: Truth alone triumphs.[43]

- Nepal: Janani Janmabhoomischa Swargadapi Gariyasi meaning: Mother and motherland are superior to heaven.

- Indonesia: In Indonesia, Sanskrit are usually widely used as terms and mottoes of the armed forces and other national organizations (See: Indonesian Armed Forces mottoes). Rastra Sewakottama (राष्ट्र सेवकोत्तम; People's Main Servants) is the official motto of the Indonesian National Police, Tri Dharma Eka Karma(त्रीधर्म एक कर्म) is the official motto of the Indonesian Military, Kartika Eka Paksi (कार्तिक एक पक्षी; Unmatchable Bird with Noble Goals) is the official motto of the Indonesian Army, Adhitakarya Mahatvavirya Nagarabhakti (अधीतकार्य महत्ववीर्य नगरभक्ती; Hard-working Knights Serving Bravery as Nations Hero") is the official motto of the Indonesian Military Academy, Upakriya Labdha Prayojana Balottama (उपकृया लब्ध प्रयोजन बालोत्तम; "Purpose of The Unit is to Give The Best Service to The Nation by Finding The Perfect Soldier") is the official motto of the Army Psychological Corps, Karmanye Vadikaraste Mafalesu Kadachana (कर्मायने वदीकरस्ते माफलेशु कदाचन; "Working Without Counting The Profit and Loss") is the official motto of the Air-Force Special Forces (Paskhas), Jalesu Bhumyamcha Jayamahe (जलेशु भूम्यं च जयमहे; "On The Sea and Land We Are Glorious") is the official motto of the Indonesian Marine Corps, and there are more units and organizations in Indonesia either Armed Forces or civil which use the Sanskrit language respectively as their mottoes and other purposes. Although Indonesia is a Muslim-majority country, it still has major Hindu and Indian influence since pre-historic times until now culturally and traditionally especially in the islands of Java and Bali.

Many of India's and Nepal's scientific and administrative terms are named in Sanskrit. The Indian guided missile program that was commenced in 1983 by the Defence Research and Development Organisation has named the five missiles (ballistic and others) that it developed Prithvi, Agni, Akash, Nag and the Trishul missile system. India's first modern fighter aircraft is named HAL Tejas.

Historical usage

Origin and development

Sanskrit is a member of the Indo-Iranian subfamily of the Indo-European family of languages. Its closest ancient relatives are the Iranian languages Avestan and Old Persian.[44][45]

In order to explain the common features shared by Sanskrit and other Indo-European languages, the Indo-Aryan migration theory states that the original speakers of what became Sanskrit arrived in the Indian subcontinent from the north-west some time during the early second millennium BCE. Evidence for such a theory includes the close relationship between the Indo-Iranian tongues and the Baltic and Slavic languages, vocabulary exchange with the non-Indo-European Uralic languages, and the nature of the attested Indo-European words for flora and fauna.[46]

The earliest attested Sanskrit texts are religious texts of the Rigveda, from the mid-to-late second millennium BCE. No written records from such an early period survive, if they ever existed. However, scholars are confident that the oral transmission of the texts is reliable: they were ceremonial literature whose correct pronunciation was considered crucial to its religious efficacy.[47]

From the Rigveda until the time of Pāṇini (fourth century BCE) the development of the early Vedic language can be observed in other Vedic texts: the Samaveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda, Brahmanas, and Upanishads. During this time, the prestige of the language, its use for sacred purposes, and the importance attached to its correct enunciation all served as powerful conservative forces resisting the normal processes of linguistic change.[48] However, there is a clear, five-level linguistic development of Vedic from the Rigveda to the language of the Upanishads and the earliest sutras such as the Baudhayana sutras.[18]

Standardisation by Panini

The oldest surviving Sanskrit grammar is Pāṇini's Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar"). It is essentially a prescriptive grammar, i.e., an authority that defines Sanskrit, although it contains descriptive parts, mostly to account for some Vedic forms that had become rare in Pāṇini's time. Classical Sanskrit became fixed with the grammar of Pāṇini (roughly 500 BCE), and remains in use as a learned language through the present day.[49][50]

Coexistence with vernacular languages

Sanskrit linguist Madhav Deshpande says that when the term "Sanskrit" arose it was not thought of as a specific language set apart from other languages, but rather as a particularly refined or perfected manner of speaking. Knowledge of Sanskrit was a marker of social class and educational attainment in ancient India, and the language was taught mainly to members of the higher castes through the close analysis of Vyākaraṇins such as Pāṇini and Patanjali, who exhorted proper Sanskrit at all times, especially during ritual.[51] Sanskrit, as the learned language of Ancient India, thus existed alongside the vernacular Prakrits, which were Middle Indo-Aryan languages. However, linguistic change led to an eventual loss of mutual intelligibility.

Many Sanskrit dramas also indicate that the language coexisted with Prakrits, spoken by multilingual speakers with a more extensive education. Sanskrit speakers were almost always multilingual. In the medieval era, Sanskrit continued to be spoken and written, particularly by learned Brahmins for scholarly communication. This was a thin layer of Indian society, but covered a wide geography. Centres like Varanasi, Paithan, Pune and Kanchipuram had a strong presence of teaching and debating institutions, and high classical Sanskrit was maintained until British times.[51]

Decline

There are a number of sociolinguistic studies of spoken Sanskrit which strongly suggest that oral use of modern Sanskrit is limited, having ceased development sometime in the past.[52]

Sheldon Pollock argues that "most observers would agree that, in some crucial way, Sanskrit is dead".[19]:393 Pollock has further argued that, while Sanskrit continued to be used in literary cultures in India, it was never adapted to express the changing forms of subjectivity and sociality as embodied and conceptualised in the modern age.[19]:416 Instead, it was reduced to "reinscription and restatements" of ideas already explored, and any creativity was restricted to hymns and verses.[19]:398 A notable exception are the military references of Nīlakaṇṭha Caturdhara's 17th-century commentary on the Mahābhārata.[53]

Hatcher argues that modern works continue to be produced in Sanskrit,[54] while according to Hanneder,

On a more public level the statement that Sanskrit is a dead language is misleading, for Sanskrit is quite obviously not as dead as other dead languages and the fact that it is spoken, written and read will probably convince most people that it cannot be a dead language in the most common usage of the term. Pollock's notion of the "death of Sanskrit" remains in this unclear realm between academia and public opinion when he says that "most observers would agree that, in some crucial way, Sanskrit is dead."— Hanneder[55]

Hanneder has also argued that modern works in Sanskrit are either ignored or their "modernity" contested.[56]

When the British imposed a Western-style education system in India in the 19th century, knowledge of Sanskrit and ancient literature continued to flourish as the study of Sanskrit changed from a more traditional style into a form of analytical and comparative scholarship mirroring that of Europe.[57]

Public education and popularisation

Adult and continuing education

Attempts at reviving the Sanskrit language have been undertaken in the Republic of India since its foundation in 1947 (it was included in the 14 original languages of the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution).

Samskrita Bharati is an organisation working for Sanskrit revival. The "All-India Sanskrit Festival" (since 2002) holds composition contests. The 1991 Indian census reported 49,736 fluent speakers of Sanskrit. Sanskrit learning programmes also feature on the lists of most AIR broadcasting centres. The Mattur village in central Karnataka claims to have native speakers of Sanskrit among its population.[58] Inhabitants of all castes learn Sanskrit starting in childhood and converse in the language.[59] Even the local Muslims converse in Sanskrit. Historically, the village was given by king Krishnadevaraya of the Vijayanagara Empire to Vedic scholars and their families, while people in his kingdom spoke Kannada and Telugu. Another effort concentrates on preserving and passing along the oral tradition of the Vedas, www

School curricula

The Central Board of Secondary Education of India (CBSE), along with several other state education boards, has made Sanskrit an alternative option to the state's own official language as a second or third language choice in the schools it governs. In such schools, learning Sanskrit is an option for grades 5 to 8 (Classes V to VIII). This is true of most schools affiliated with the Indian Certificate of Secondary Education (ICSE) board, especially in states where the official language is Hindi. Sanskrit is also taught in traditional gurukulas throughout India.[61]

In the West

St James Junior School in London, England, offers Sanskrit as part of the curriculum.[62] In the United States, since September 2009, high school students have been able to receive credits as Independent Study or toward Foreign Language requirements by studying Sanskrit, as part of the "SAFL: Samskritam as a Foreign Language" program coordinated by Samskrita Bharati.[63] In Australia, the Sydney private boys' high school Sydney Grammar School offers Sanskrit from years 7 through to 12, including for the Higher School Certificate.[64]

Universities

A list of Sanskrit universities is given below in chronological order of establishment:

| Year Est. | Name | Location |

|---|---|---|

| 1791 | Sampurnanand Sanskrit University | Varanasi |

| 1876 | Sadvidya Pathashala | Mysore |

| 1961 | Kameshwar Singh Darbhanga Sanskrit University | Darbhanga |

| 1962 | Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha | Tirupati |

| 1962 | Shri Lal Bahadur Shastri Rashtriya Sanskrit Vidyapeetha | New Delhi |

| 1970 | Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan | New Delhi |

| 1981 | Shri Jagannath Sanskrit University | Puri |

| 1986 | Nepal Sanskrit University | Nepal |

| 1993 | Sree Sankaracharya University of Sanskrit | Kalady, Kerala |

| 1997 | Kavikulaguru Kalidas Sanskrit University | Ramtek |

| 2001 | Jagadguru Ramanandacharya Rajasthan Sanskrit University | Jaipur |

| 2005 | Shree Somnath Sanskrit University | Somnath-Veraval |

| 2008 | Maharshi Panini Sanskrit Evam Vedic Vishwavidyalaya | Ujjain |

| 2011 | Karnataka Samskrit University | Bangalore |

Many universities throughout the world train and employ Sanskrit scholars, either within a separate Sanskrit department or as part of a broader focus area, such as South Asian studies or Linguistics. For example, Delhi university has about 400 Sanskrit students, about half of which are in post-graduate programmes.[37]

European scholarship

European scholarship in Sanskrit, begun by Heinrich Roth (1620–1668) and Johann Ernst Hanxleden (1681–1731), is considered responsible for the discovery of an Indo-European language family by Sir William Jones (1746–1794). This research played an important role in the development of Western philology, or historical linguistics.[65]

Sir William Jones was one of the most influential philologists of his time. He told The Asiatic Society in Calcutta on 2 February 1786:

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and in the forms of grammar, than could have been produced by accident; so strong, indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists.[66]

British attitudes

Orientalist scholars of the 18th century like Sir William Jones marked a wave of enthusiasm for Indian culture and for Sanskrit. According to Thomas Trautmann, after this period of "Indomania", a certain hostility to Sanskrit and to Indian culture in general began to assert itself in early 19th century Britain, manifested by a neglect of Sanskrit in British academia. This was the beginning of a general push in favour of the idea that India should be culturally, religiously and linguistically assimilated to Britain as far as possible. Trautmann considers two separate and logically opposite sources for the growing hostility: one was "British Indophobia", which he calls essentially a developmentalist, progressivist, liberal, and non-racial-essentialist critique of Hindu civilisation as an aid for the improvement of India along European lines; the other was scientific racism, a theory of the English "common-sense view" that Indians constituted a "separate, inferior and unimprovable race".[67]

Phonology

Classical Sanskrit distinguishes about 36 phonemes; the presence of allophony leads the writing systems to generally distinguish 48 phones, or sounds. The sounds are traditionally listed in the order vowels (Ac), diphthongs (Hal), anusvara and visarga, plosives (Sparśa), nasals, and finally the liquids and fricatives, written in the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) as follows:

- a ā i ī u ū ṛ ṝ ḷ ḹ; e ai o au

- ṃ ḥ

- k kh g gh ṅ; c ch j jh ñ; ṭ ṭh ḍ ḍh ṇ; t th d dh n; p ph b bh m

- y r l v; ś ṣ s h

Writing system

Sanskrit originated in an oral society, and the oral tradition was maintained through the development of early classical Sanskrit literature.[68] Some scholars such as Jack Goody suggest that the Vedic Sanskrit texts are not the product of an oral society, basing this view by comparing inconsistencies in the transmitted versions of literature from various oral societies such as the Greek, Serbia and other cultures, then noting that the Vedic literature is too consistent and vast to have been composed and transmitted orally across generations, without being written down.[69] These scholars add that the Vedic texts likely involved both a written and oral tradition, calling it a "parallel products of a literate society".[69][70]

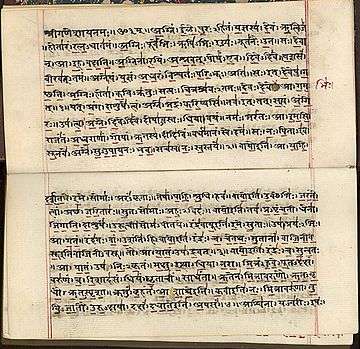

Sanskrit has no native script of its own, and historical evidence suggests that it has been written in various scripts on a variety of medium such as palm leaves, cloth, paper, rock and metal sheets, at least by the time of arrival of Alexander the Great in northwestern Indian subcontinent in 1st millennium BCE.[3]

The earliest known rock inscriptions in Sanskrit date to the mid second century CE.[71] They are in the Brahmi script, which was originally used for Prakrit, not Sanskrit. It has been described as a paradox that the first evidence of written Sanskrit occurs centuries later than that of the Prakrit languages which are its linguistic descendants.[68] In northern India, there are Brāhmī inscriptions dating from the third century BCE onwards, the oldest appearing on the famous Prakrit pillar inscriptions of king Ashoka. The earliest South Indian inscriptions in Tamil Brahmi, written in early Tamil, belong to the same period. When Sanskrit was written down, it was first used for texts of an administrative, literary or scientific nature. The sacred hymns and verse were preserved orally, and were set down in writing "reluctantly" (according to one commentator), and at a comparatively late date.[72][73]

Brahmi evolved into a multiplicity of Brahmic scripts, many of which were used to write Sanskrit. Roughly contemporary with the Brahmi, Kharosthi was used in the northwest of the subcontinent. Sometime between the fourth and eighth centuries, the Gupta script, derived from Brahmi, became prevalent. Around the eighth century, the Śāradā script evolved out of the Gupta script. The latter was displaced in its turn by Devanagari in the 11th or 12th century, with intermediary stages such as the Siddhaṃ script. In East India, the Bengali alphabet, and, later, the Odia alphabet, were used.

In the south, where Dravidian languages predominate, scripts used for Sanskrit include the Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, the Malayalam and Grantha alphabets.[74][75]

Romanisation

Since the late 18th century, Sanskrit has been transliterated using the Latin alphabet. The system most commonly used today is the IAST (International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration), which has been the academic standard since 1888. ASCII-based transliteration schemes have also evolved because of difficulties representing Sanskrit characters in computer systems. These include Harvard-Kyoto and ITRANS, a transliteration scheme that is used widely on the Internet, especially in Usenet and in email, for considerations of speed of entry as well as rendering issues. With the wide availability of Unicode-aware web browsers, IAST has become common online. It is also possible to type using an alphanumeric keyboard and transliterate to Devanagari using software like Mac OS X's international support.

European scholars in the 19th century generally preferred Devanagari for the transcription and reproduction of whole texts and lengthy excerpts. However, references to individual words and names in texts composed in European Languages were usually represented with Roman transliteration. From the 20th century onwards, because of production costs, textual editions edited by Western scholars have mostly been in Romanised transliteration.[76]

Grammar

The Sanskrit grammatical tradition, Vyākaraṇa, one of the six Vedangas, began in the late Vedic period and culminated in the Aṣṭādhyāyī of Pāṇini, which consists of 3990 sutras (ca. fifth century BCE). About a century after Pāṇini (around 400 BCE), Kātyāyana composed Vārtikas on the Pāṇini sũtras. Patanjali, who lived three centuries after Pāṇini, wrote the Mahābhāṣya, the "Great Commentary" on the Aṣṭādhyāyī and Vārtikas. Because of these three ancient Vyākaraṇins (grammarians), this grammar is called Trimuni Vyākarana. To understand the meaning of the sutras, Jayaditya and Vāmana wrote a commentary, the Kāsikā, in 600 CE. Pāṇinian grammar is based on 14 Shiva sutras (aphorisms), where the whole mātrika (alphabet) is abbreviated. This abbreviation is called the Pratyāhara.[77]

Sanskrit verbs are categorized into ten classes, which can be conjugated to form the present, imperfect, imperative, optative, perfect, aorist, future, and conditional moods and tenses. Before Classical Sanskrit, older forms also included a subjunctive mood. Each conjugational ending conveys person, number, and voice.

Nouns are highly inflected, including three grammatical genders, three numbers, and eight cases. Nominal compounds are common, and can include over 10 word stems.

Word order is free, though there is a strong tendency toward subject–object–verb, the original system of Vedic prose.

Influence on other languages

Indic languages

Sanskrit has greatly influenced the languages of India that grew from its vocabulary and grammatical base; for instance, Hindi is a "Sanskritised register" of the Khariboli dialect. All modern Indo-Aryan languages, as well as Munda and Dravidian languages, have borrowed many words either directly from Sanskrit (tatsama words), or indirectly via middle Indo-Aryan languages (tadbhava words). Words originating in Sanskrit are estimated at roughly fifty percent of the vocabulary of modern Indo-Aryan languages, as well as the literary forms of Malayalam and Kannada.[17] Literary texts in Telugu are lexically Sanskrit or Sanskritised to an enormous extent, perhaps seventy percent or more.[78] Marathi is another prominent language in Western India, that derives most of its words and Marathi grammar from Sanskrit.[79] Sanskrit words are often preferred in the literary texts in Marathi over corresponding colloquial Marathi word.[80]

Interaction with other languages

Sanskrit has also influenced Sino-Tibetan languages through the spread of Buddhist texts in translation. Buddhism was spread to China by Mahayana missionaries sent by Ashoka, mostly through translations of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit. Many terms were transliterated directly and added to the Chinese vocabulary. Chinese words like 剎那 chànà (Devanagari: क्षण kṣaṇa 'instantaneous period') were borrowed from Sanskrit. Many Sanskrit texts survive only in Tibetan collections of commentaries to the Buddhist teachings, the Tengyur.[81]

In Southeast Asia, languages such as Thai and Lao contain many loanwords from Sanskrit, as do Khmer. For example, in Thai, Ravana, the emperor of Lanka, is called Thosakanth, a derivation of his Sanskrit name Dāśakaṇṭha "having ten necks".

Many Sanskrit loanwords are also found in Austronesian languages, such as Javanese, particularly the older form in which nearly half the vocabulary is borrowed.[82] Other Austronesian languages, such as traditional Malay and modern Indonesian, also derive much of their vocabulary from Sanskrit, albeit to a lesser extent, with a larger proportion derived from Arabic. Similarly, Philippine languages such as Tagalog have some Sanskrit loanwords, although more are derived from Spanish. A Sanskrit loanword encountered in many Southeast Asian languages is the word bhāṣā, or spoken language, which is used to refer to the names of many languages.[83] English also has words of Sanskrit origin.

In popular culture

Satyagraha, an opera by Philip Glass, uses texts from the Bhagavad Gita, sung in Sanskrit.[84][85] The closing credits of The Matrix Revolutions has a prayer from the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The song "Cyber-raga" from Madonna's album Music includes Sanskrit chants,[86] and Shanti/Ashtangi from her 1998 album Ray of Light, which won a Grammy, is the ashtanga vinyasa yoga chant.[87] The lyrics include the mantra Om shanti.[88] Composer John Williams featured choirs singing in Sanskrit for Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom and in Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace.[89][90] The theme song of Battlestar Galactica 2004 is the Gayatri Mantra, taken from the Rigveda.[91] The lyrics of "The Child In Us" by Enigma also contains Sanskrit verses.[92] A joke in the 1994 comedy film PCU involved a minor character at an American university that was majoring in Sanskrit.[93]

See also

References and notes

- ↑ The exact pronunciation in Classical Sanskrit is unknown. For alternative pronunciations of ṃ, see Anusvara § Sanskrit

- ↑ Uta Reinöhl (2016). Grammaticalization and the Rise of Configurationality in Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. pp. xiv, 1–16. ISBN 978-0-19-873666-0.

- 1 2 "Comparative speaker's strength of scheduled languages − 1971, 1981, 1991 and 2001". Census of India, 2001. Office of the Registrar and Census Commissioner, India. Archived from the original on 11 April 2009. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- 1 2 Banerji, Sures (1989). A companion to Sanskrit literature : spanning a period of over three thousand years, containing brief accounts of authors, works, characters, technical terms, geographical names, myths, legends, and several appendices. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. p. 672 with footnotes. ISBN 978-81-208-0063-2.

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Sanskrit". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Burrow, T. (2001). The Sanskrit Language. Faber: Chicago p. v & ch. 1

- ↑ "Indian Constitution Art.344(1) & Art.345" (PDF). Web.archive.org. 4 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2007. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Sanskrit is second official language in Uttarakhand". The Hindustan Times. 19 January 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Benware, Wilbur (1974). The study of Indo-European vocalism in the 19th century : from the beginnings to Whitney and Scherer : a critical-historical account. Amsterdam: Benjamins. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-90-272-0894-1.

- ↑ "Sheldon Pollock offers scholarly opinion on Sanskrit - a language Govt. seems keen to massify".

- ↑ "Sanskrit as a language of science".

- ↑ Katju, Markandey (5 December 2011). "Markandey Katju: What is India?". The Times of India.

- ↑ Williams, Monier (2004). A Sanskrit-English dictionary : etymologically and philologically arranged with special reference to cognate Indo-European languages. New Delhi: Bharatiya Granth Niketan. p. 1120. ISBN 978-81-89211-00-4.

- ↑ Southworth, Franklin (2005). Linguistic archaeology of South Asia (PDF). London: RoutledgeCurzon. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-203-41291-6.

- 1 2 Nedi︠a︡lkov, V. P. (2007). Reciprocal constructions. Amsterdam Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. p. 710. ISBN 978-90-272-2983-0.

- ↑ MacDonell, Arthur (2004). A History Of Sanskrit Literature (in Norwegian). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-0619-2.

- ↑ Houben, Jan (1996). Ideology and status of Sanskrit : contributions to the history of the Sanskrit language. Leiden New York: E.J. Brill. p. 11. ISBN 90-04-10613-8.

- 1 2 Staal, J. F. (1963). "Sanskrit and Sanskritization". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 22 (3): 261. doi:10.2307/2050186. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- 1 2 Witzel, M (1997). Inside the texts, beyond the texts: New approaches to the study of the Vedas (PDF). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Retrieved 28 October 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Pollock, Sheldon (2001). "The Death of Sanskrit". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press (CUP). 43 (2): 392–426. doi:10.1017/s001041750100353x. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ↑ Oberlies, Thomas (2003). A grammar of epic Sanskrit. Berlin New York: Walter de Gruyter. pp. xxvii – xxix. ISBN 3-11-014448-4.

- ↑ Edgerton, Franklin (2004). Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit grammar and dictionary. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-215-1110-0.

- ↑ Tiwari, Bholanath (1955), भाषा विज्ञान (Bhasha Vijnan)

- ↑ "This village speaks gods language – India – The Times of India". The Times of India. 13 August 2005. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Ghosh, Aditya (20 September 2008). "Sanskrit boulevard". Hindustan Times. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Bhaskar, B.V.S. (31 July 2009). "Mark of Sanskrit". The Hindu.

- ↑ "Orissa's Sasana village – home to Sanskrit pundits! !". The India Post. 9 April 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ National Population and Housing Census 2011 (PDF) (Report). 1. Kathmandu: Central Bureau of Statistics, Government of Nepal. November 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 December 2013.

- ↑ "Writ Petition on Sanskrit". JD Supra. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ "PIL seeks minority status for Sanskrit". The Financial World. 15 October 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ "Mother language 'Sanskrit' needs urgent protection". GoI Monitor. 8 November 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-10.

- ↑ Prajapati, Manibhai (2005). Post-independence Sanskrit literature : a critical survey (1 ed.). New Delhi: Standard publishers India.

- ↑ Ranganath, S (2009). Modern Sanskrit Writings in Karnataka (PDF) (1st ed.). New Delhi: Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan. p. 7. ISBN 978-81-86111-21-5. Retrieved 28 October 2014.:

Contrary to popular belief, there is an astonishing quality of creative upsurge of writing in Sanskrit today. Modern Sanskrit writing is qualitatively of such high order that it can easily be treated on par with the best of Classical Sanskrit literature, It can also easily compete with the writings in other Indian languages.

- ↑ "Adhunika Sanskrit Sahitya Pustakalaya". Rashtriya Sanskrit Sansthan. Retrieved 28 October 2014.:

The latter half of the nineteenth century marks the beginning of a new era in Sanskrit literature. Many of the modern Sanskrit writings are qualitatively of such high order that they can easily be treated at par with the best of classical Sanskrit works, and they can also be judged in contrast to the contemporary literature in other languages.

- ↑ "Sanskrit's first Jnanpith winner is a 'poet by instinct'". The Indian Express. 14 Jan 2009.

- ↑ "Samveda". Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ BBC. "BBC – Awards for World Music 2008".

- 1 2 3 Mayank Austen Soofi (23 November 2012). "Delhi's Belly | Sanskrit-vanskrit". Livemint. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ "News on Air". News On Air. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ "News archive search". Newsonair. 15 August 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ "Doordarshan News Live webcast". Webcast.gov.in. Retrieved 2012-12-06.

- ↑ "Is Sanskrit (In)dispensable for Hindu Liturgy?". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ Vaishna Roy. "Sanskrit deserves more than slogans". The Hindu.

- ↑ Upadhyay, Pankaj; Jaiswal, Umesh Chandra; Ashish, Kumar (2014). "TranSish: Translator from Sanskrit to English-A Rule based Machine Translation". International Journal of Current Engineering and Technology E-ISSN: 2277–4106.

- ↑ Levin, Saul. Semitic and Indo-European, Volume 2. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 431.

- ↑ Edwin Francis Bryant; Laurie L. Patton. The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Psychology Press. p. 208.

- ↑ Masica, Colin (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages (PDF). Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 36–38. ISBN 0-521-23420-4.

- ↑ Michael Meier-Brügger (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. p. 20. ISBN 978-3-11-017433-5.

- ↑ A. Berriedale Keith (1993). A history of Sanskrit literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. p. 4. ISBN 978-81-208-1100-3.

- ↑ Anupama Raju. "A man of languages". The Hindu.

- ↑ "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 2, page 263 -- Imperial Gazetteer of India -- Digital South Asia Library". uchicago.edu.

- 1 2 Deshpande, Madhav (2011), "Efforts to Vernacularize Sanskrit: Degree of Success and Failure", in Joshua Fishman, Ofelia Garcia, Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts, 2, Oxford University Press, p. 218, ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1

- ↑ Hock, Hans Henrich (1983). Kachru, Braj B, ed. "Language-death phenomena in Sanskrit: grammatical evidence for attrition in contemporary spoken Sanskrit". Studies in the linguistic Sciences. Illinois Working Papers. 13:2.

- ↑ Minkowski, Christopher (2004). "Nilakantha's instruments of war:Modern, vernacular, barbarous". The Indian Economic and Social History Review. SAGE. 41 (4): 365–385. doi:10.1177/001946460404100402. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ↑ Hatcher, B. A. (2007). "Sanskrit and the morning after: The metaphorics and theory of intellectual change". Indian Economic. SAGE. 44 (3): 333–361. doi:10.1177/001946460704400303. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ↑ Hanneder, J. (2002). "On "The Death of Sanskrit"". Indo-Iranian Journal. Brill Academic Publishers. 45 (4): 293–310. doi:10.1023/a:1021366131934. Retrieved 2014-10-29.

- ↑ Hanneder, J. (2009), "Modernes Sanskrit: eine vergessene Literatur", in Straube, Martin; Steiner, Roland; Soni, Jayandra; Hahn, Michael; Demoto, Mitsuyo, Pāsādikadānaṃ : Festschrift für Bhikkhu Pāsādika, Indica et Tibetica Verlag, pp. 205–228

- ↑ Seth, Sanjay (2007). Subject lessons : the Western education of colonial India. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4105-5.

- ↑ "Karnataka's Mattur: A Sanskrit speaking village with almost one IT professional per family".

- ↑ Viswanathan, Trichur. S. (4 April 2013). "Tale of two villages". The Hindu.

- ↑ Pragna, Volume 8. Pragna Bharati.

- ↑ "In 2013, UPA to CBSE: Make Sanskrit a must". The Indian Express. 4 December 2014.

- ↑ "Sanskrit thriving in UK schools". NDTV.com. 28 June 2010.

- ↑ Varija Yelagalawadi. "Why SAFL?". Samskrita Bharati USA. Archived from the original on 12 May 2015.

- ↑ Sydney Grammar School. "Headmaster's Introduction".

- ↑ Friedrich Max Müller (1859). A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature So Far as it Illustrates the Primitive Religion of the Brahmans. Williams and Norgate. p. 1.

- ↑ Vasunia, Phiroze (2013). The Classics and Colonial India. Oxford University Press. p. 17.

- ↑ Thomas R. Trautmann (2004). Aryans and British India. Yoda Press. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-81-902272-1-6. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- 1 2 Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy a Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 7, 86. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- 1 2 Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–121. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

- ↑ Donald S. Lopez Jr. (1995). "Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna". Numen. Brill Academic. 42 (1): 21–47. JSTOR 3270278.

- ↑ c150 - Junagadh rock inscription of Rudradaman: Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- ↑ Masica, Colin (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages. Cambridge New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil epigraphy from the earliest times to the sixth century A.D. Chennai, India Cambridge, MA Cambridge, Mass. London, England: Cre-A Dept. of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University Distributed by Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- ↑ "Tamil Brahmi script in Egypt". The Hindu. 21 November 2007.

- ↑ "Harappan people used an older form of Brahmi script: Expert". The Times of India.

- ↑ "Modern Transcription of Sanskrit". autodidactus.org.

- ↑ Abhyankar, Kashinath (1986). A Dictionary of Sanskrit Grammar (PDF). Baroda: Maharaja Sayajirao University.

- ↑ Rao, Velcheru (2002). Classical Telugu poetry an anthology. Berkeley, Calif: University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-520-22598-5.

- ↑ Sugam Marathi Vyakaran & Lekhana. 2007. Nitin publications. Author: M.R.Walimbe

- ↑ Carey, William (1805). A Grammar of the Marathi Language. Serampur [sic]: Serampore Mission Press. ISBN 9781108056311.

- ↑ Gulik, R. H. (2001). Siddham : an essay on the history of Sanskrit studies in China and Japan. New Delhi: International Academy of Indian Culture and Aditya Prakashan. pp. 5–133. ISBN 978-81-7742-038-8.

- ↑ Zoetmulder, P. J. (1982). Old Javanese-English Dictionary.

- ↑ Joshi, Manoj. Passport India 3rd Ed., eBook. World Trade Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Vibhuti Patel (18 December 2011). "Gandhi as operatic hero". The Hindu.

- ↑ Rahim, Sameer (4 December 2013). "The opera novice: Satyagraha by Philip Glass". Telegraph. london.

- ↑ Morgan, Les (2011). Croaking frogs : a guide to Sanskrit metrics and figures of speech. Los Angeles: Mahodara Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-4637-2562-4.

- ↑ Doval, Nikita (24 June 2013). "Classic conversations". The Week. Archived from the original on 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Yoga and Music". Yoga Journal.

- ↑ "Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (John Williams)". Filmtracks. 11 November 2008. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Episode I FAQ". Star Wars Faq. Archived from the original on 11 October 2003.

- ↑ "Battlestar Galactica (TV Series 2004–2009)". IMDb.

- ↑ "The Child In Us Lyrics – Enigma". Lyricsfreak.com. Retrieved 2013-01-27.

- ↑ "PCU (1994) Quotes". IMDb.

Further reading

- Maurer, Walter (2001). The Sanskrit language : an introductory grammar and reader. Surrey, England: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1382-4.

External links

| Sanskrit edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sanskrit |

| For a list of words relating to Sanskrit, see the Sanskrit language category of words in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: Sanskrit |

| Wikivoyage has a phrasebook for Sanskrit. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sanskrit. |

- Sanskrit Lessons (free online from the Linguistics Research Center at UT Austin)

- Samskrita Bharati, organisation supporting the usage of Sanskrit

- Sanskrit Documents—Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc.

- Sanskrit texts at Sacred Text Archive

- Sanskrit Manuscripts in Cambridge Digital Library

_in_Sanskrit.svg.png)