Artuqids

| Artuqid State | ||||||||||

| Artuklu Devleti | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

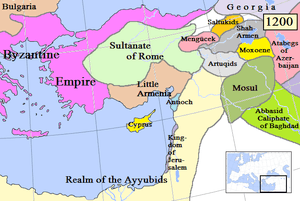

Map of Anatolia and surrounding in AD 1200 | ||||||||||

| Capital | Hasankeyf, later Diyarbakır, Harput, finally Mardin | |||||||||

| Languages | Turkish | |||||||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | |||||||||

| Government | Beylik | |||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Collapse of the Sultanate of Rum | 1101 | ||||||||

| • | Annexation by Kara Koyunlu | 1409 | ||||||||

| Currency | dinar | |||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The Artquids or Artuqid dynasty (Modern Turkish: Artuklu Beyliği or Artıklılar, sometimes also spelled as Artukid, Ortoqid or Ortokid; Turkish plural: Artukoğulları; Azeri Turkish : Artıqlı) was a Turkmen dynasty[1] that ruled in Eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Zaheer-ul-Daulah Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz and ruled one of the Turkmen atabeyliks of the Seljuk Empire. The Artuqid rulers viewed the state as the common property of the dynasty members. Three branches of the family ruled in the region: Sokmen Bey's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Necmeddin Ilgazi's branch ruled from Mardin between 1106 and 1186 (and until 1409 as vassals); and the Mayyafariqin Artuqid line ruled in Harput starting in 1112, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

Artuqid rulers commissioned many public buildings, such as mosques, bazaars, bridges, hospitals and baths for the benefit of their subjects. They left an important cultural heritage by contributing to literature and the art of metalworking. The door and door handles of the great Mosque of Cizre are unique examples of Artuqid metal working craftsmanship, which can be seen in the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum in Istanbul, Turkey.

History

The dynasty was founded by Artuk Bey, son of Eksük, a general originally under Malik Shah I and then under the Seljuq emir of Damascus, Tutush I. Tutush appointed Artuq governor of Jerusalem in 1086. Artuq died in 1091, and his sons Sökmen and Ilghazi were expelled from Jerusalem by the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah in 1098; the Fatimids lost the city to the crusaders the following year.

Sokman and Ilghazi set themselves up in Diyarbakır, Mardin, and Hasankeyf in the Jezirah, where they came into conflict with the sultanate of Great Seljuq. Sokman, bey of Mardin, defeated the crusaders at the Battle of Harran in 1104. Ilghazi succeeded Sokman in Mardin and imposed his control over Aleppo at the request of the qadi Ibn al-Khashshab in 1118. In 1119 Ilgazi defeated the crusader Principality of Antioch at the Battle of Ager Sanguinis.

In 1121 a Seljuq-Artuqid alliance, commanded by Mehmed I of Great Seljuq and Ilghazi, was defeated by the Kingdom of Georgia at the Battle of Didgori. Ilghazi died in 1122, and although his nephew Balak nominally controlled Aleppo, the city was really controlled by Ibn al-Khashshab. Al-Kashshab was assassinated in 1125, and Aleppo fell under the control of Zengi of Mosul. After the death of Balak, the Artuqids were split between Harput, Hasankeyf and Mardin. Sokman's son Davud, bey of Hasankeyf, died in 1144, and was succeeded by his son Kara Aslan. Kara Aslan allied with Joscelin II of Edessa against the Zengids, and while Joscelin was away in 1144, Zengi recaptured Edessa, the first of the Crusader states to fall (see Siege of Edessa). Hasankeyf became a vassal of Zengi as well.

Kara Aslan's son Nur ad-Din Muhammad allied with the Ayyubid sultan Saladin against the Sultan of Rum Kilij Arslan II, whose daughter had married Nur ad-Din Muhammad. In the peace settlement with Kilij Arslan, Saladin gained control of the Artuqid territory, even though the Artuqids were still technically vassals of Mosul, which Saladin did not yet control. With Artuqid support, however, Saladin eventually took control of Mosul as well.

The Artuklu dynasty remained in nominal command of upper Mesopotamia, but their power declined under Ayyubid rule. The Hasankeyf branch conquered Diyarbakır in 1198 and its center was moved here, but was demolished by the Ayyubids in 1231 when it attempted to form an alliance with the Seljuqs. The Harput branch was destroyed by the Sultanate of Rum due to following a slippery policy between the Ayyubids and Seljuqs. The Mardin branch survived for longer, but as a vassal of the Ayyubids, Sultanate of Rum, Il-Khanate and the Timurids. Karakoyunlu captured Mardin and finally put an end to Artuklu rule in 1409.

Art

Despite their constant preoccupation with war, members of the Artuklu dynasty left many architectural monuments.

They made the most significant additions to Diyarbakır City Walls. Urfa Gate was rebuilt by Muhammad, son of Kara Arslan. In the same area of the western wall, south of Urfa Gate, two imposing towers, Ulu Beden and Yedi Kardeş were commissioned in 1208 by the Artuklu ruler Salih Mahmud who designed the Yedi Kardeş tower himself and apposed the Artukid double-headed eagle on its walls.

A large caravanserai in Mardin as well as the civil engineering feat of Malabadi Bridge are still in regular use in our day. The partially standing Old Bridge, Hasankeyf, was built in 1116 by Kara Arslan.

The Great Mosques of Mardin and Silvan were possibly but in any case considerably developed over the 12th century by several Artuklu rulers on the basis of existing Seljuq edifices. The congregational mosque of Dunaysir (now Kızıltepe) was commissioned by Artuklu Bey Yülük Arslan (1184–1203) and completed after his death in 1204 by his brother Artuk Arslan (1203–1239).

Coinage

-

Fakhr al-Din Qara Arslan, bronze dirham, 559 AH (1163/4 CE)

-

Nasir al-Din Artuq Arslan, bronze dirham, 620 AH (1223/4 CE)

-

Nasir al-Din Mahmud, dirham, 619 AH (1213/4 CE)

List of rulers

Hısnkeyfa Branch (Its center initially Hısnkeyfa, moved to Amid in 1183)

- Müineddevle Sökmen (1098-1104)

- İbrahim (1104-1109)

- Rükneddin Davud (1109-1144)

- Ebulharis Fahreddin Karaaslan (1144-1167)

- Nureddin Muhammed (1167-1185)

- Mesud Kutbeddin (1185-1200)

- Salih Nasreddin Mahmud (1200-1222)

- Mesud Rükneddin Mevdud (1222-1231)

To Ayyubids.

Harput Branch (It was initially part of Hısnkeyfa one till 1185)

- İmadeddin Ebubekir (1185-1203)

- Nizameddin Ebubekir (1203-1223)

- Nizameddin İbrahim (1223-1224)

- Şemsüddevle Süleyman (1224)

- İzzeddin Ahmed (1224-1234)[2]

Mardin Branch

- Necmeddin İlgazi (1107–1122)

- Hüsameddin Timurtaş (1122-1154)

- Necmeddin Alpı (1154-1176)

- Kutbeddin İlgazi (1176-1184)

- Hüsameddin Yavlak Yörükaslan (1184-1201)

- Mansur Nasreddin Artuk Arslan (1201-1239)

- Said Necmeddin Gazi (1239-1260)

- Muzaffer Ebulfeth Fahreddin Karaaslan (1260-1292)

- Semseddin Davud (1292-1294)

- Mansur Necmeddin Gazi (1294-1312)

- Adil İmadeddin Ali Alpı (1312)

- Salih Şemseddin (1312-1363)

- Mansur Ahmed (1363-1367)

- Salih Mahmud (1367)

- Muzaffer Davud (1367-1376)

- Zahir Mecdeddin İsa (1376-1407)

- Salih Şihabeddin Ahmed (1407-1409)

To Kara Koyunlu

Aleppo subbranch (It was bounded to Mardin branch)

- İlgazi Bey (1117-1121)

- Eburebi Bedriddevle Süleyman (1121-1123)

- Belek Ghazi (1123-1124)

- Timurtaş (1124)

- İzzeddin Ahmed (1224-1234)[3]

to Zengids

See also

References

- ↑ Clifford Edmund Bosworth, The Mediaeval Islamic Underworld: The Banū Sāsān in Arabic life and lore, (E.J. Brill, 1976), 107.

- ↑ Öztuna, Yılmaz, "Devletler ve Hanedanlar" Cilt:2, Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara (1996), s.43

- ↑ Öztuna, Yılmaz, "Devletler ve Hanedanlar" Cilt:2, Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara (1996), s.43-44

Sources

- (limited preview) Clifford Edmund Bosworth (2004). The New Islamic Dynasties: A Chronological and Genealogical Manual ISBN 0-7486-2137-7. Edinburgh University Press.

- Carole Hillenbrand, A Muslim Principality in Crusader Times: The Early Artuqid State. Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut, 1990.

- Carole Hillenbrand, The Crusades: Islamic Perspectives. Routledge, 2000.

- (Book cover) Oktay Aslanapa (1991). Anadolu'da ilk Türk mimarisi: Başlangıcı ve gelişmesi (Early Turkish architecture in Anatolia: Beginnings and development) ISBN 975-16-0264-5 (in Turkish). AKM Publications, Ankara.

- P.M. Holt, The Age of the Crusades: The Near East from the Eleventh Century to 1517. Longman, 1989.

- Steven Runciman, A History of the Crusades, vol. II. Cambridge University Press, 1952.

- Kenneth Setton, ed., A History of the Crusades. Madison: 1969–1989 (available online).

External links

- (fact sheet) "Hasankeyf Bridge, Hasankeyf" Check

|url=value (help). ArchNet. - Mustafa Güler, İlknur Aktuğ Kolay. (full text) "12. yüzyıl Anadolu Türk Camileri (12th century Turkish mosques in Anatolia" Check

|url=value (help) (PDF) (in Turkish). Istanbul Technical University Magazine (İtüdergi).