Kingdom of Georgia

| Kingdom of Georgia | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| საქართველოს სამეფო Sakartvelos Samepo | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

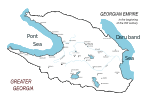

Kingdom of Georgia in 1184-1230 at the peak of its might | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Kutaisi (1008-1122) Tbilisi (1122-1490) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Georgian | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Eastern Orthodox Christianity | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | |||||||||||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 978-1014 | Bagrat III (first) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | 1446-1465 | George VIII (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | High Middle Ages | |||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Established | 1008 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 1490 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Various Byzantine and Sassanian coins were minted until 12th century. Dirham came into use after 1122.[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Today part of | Countries today

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Georgia |

|---|

|

|

History by topic |

|

|

The Kingdom of Georgia (Georgian: საქართველოს სამეფო), also known as the Georgian Empire,[2][3][4][5] was a medieval monarchy which emerged in circa 1008 AD. It reached its Golden Age of political and economic strength during the reign of King David IV and Queen Tamar the Great from 11th to 13th centuries. At the peak of its dominance,the Kingdom's influence spanned from the south of modern-day Ukraine to the northern provinces of Iran, while also maintaining religious possessions in the Holy Land and Greece. A predominantly Christian, Georgian-speaking realm, it was the principal historical precursor of present-day Georgia.

Lasting for several centuries, the kingdom fell to the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, but managed to re-assert sovereignty by the 1340s. The following decades were marked by Black Death spread by the nomads, as well as numerous invasions under the leadership of Tamerlane, who devastated the country's economy, population, and urban centers. The Kingdom's geopolitical situation further worsened after the Fall of Constantinople, which effectively marked the end of the Eastern Roman Empire, Georgia's traditional ally. As a result of these processes, by the end of the 15th century Georgia turned into an isolated, fractured Christian enclave, surrounded by hostile Turco-Iranic neighbors. Renewed incursions from 1386 led to the final collapse of the kingdom into anarchy by 1466 and the mutual recognition of its constituent kingdoms of Kartli, Kakheti and Imereti as independent states between 1490 and 1493.

Origins

The ascendancy of the Bagrationi dynasty can be traced to the 8th century, when they came to rule Tao-Klarjeti. The restoration of the Georgian kingship begins in AD 888, when Adarnase IV of Iberia took the title of "King of Georgians". The United Kingdom of Georgia was established in 1008. In this year Bagrat III, son of Gurgen II, became the ruler of the Kingdom of Western Georgia (Kingdom of Abkhazeti), including the Principalities of Imereti, Samegrelo, Abkhazeti (Abkhazia), Guria and Svaneti. Bagrat's mother was Queen Gurandukht, a daughter of George II of Abkhazia.

Unification of the Georgian State

The first decades of the 9th century saw the rise of a new Georgian state in Tao-Klarjeti. Ashot Courapalate of the royal family of Bagrationi liberated from the Arabs the territories of former southern Iberia. These included the Principalities of Tao and Klarjeti, and the Earldoms of Shavsheti, Khikhata, Samtskhe, Trialeti, Javakheti and Ashotsi, which were formally a part of the Byzantine Empire, under the name of "Curopalatinate of Iberia". In practice, however, the region functioned as a fully independent country with its capital in Artanuji. The hereditary title of Curopalates was kept by the Bagrationi family, whose representatives ruled Tao-Klarjeti for almost a century. Curopalate David Bagrationi expanded his domain by annexing the city of Theodossiopolis (Karin, Karnukalaki) and the Armenian province of Basiani, and by imposing a protectorate over the Armenian provinces of Kharqi, Apakhuni, Mantsikert, and Khlat, formerly controlled by the Kaysite Arab Emirs.

The first united Georgian monarchy was formed at the end of the 10th century when Curopalate David invaded the Earldom of Kartli-Iberia. Three years later, after the death of his uncle Theodosius the Blind, King of Egrisi-Abkhazia, Bagrat III inherited the Abkhazian throne. In 1001 Bagrat added Tao-Klarjeti (Curopalatinate of Iberia) to his domain as a result of David's death. In 1008–1010, Bagrat annexed Kakheti and Hereti, thus becoming the first king of a united Georgia in both the east and west.

The second half of the 11th century was marked by the strategically significant invasion of the Seljuq Turks, who by the end of the 1040s had succeeded in building a vast nomadic empire including most of Central Asia and Persia. In 1071, the Seljuq army destroyed the united Byzantine-Armenian and Georgian forces in the Battle of Manzikert. By 1081, all of Armenia, Anatolia, Mesopotamia, Syria, and most of Georgia had been conquered and devastated by the Seljuqs in the Great Turkish Invasion. In Georgia, only the mountainous areas of Abkhazia, Svaneti, Racha, and Khevi–Khevsureti remained out of Seljuq control and served as a relatively safe havens for numerous refugees. The rest of the country was dominated by the conquerors who destroyed the cities and fortresses, looted the villages, and massacred both the aristocracy and the farming population. In fact, by the end of the 1080s, Georgians were outnumbered in the region by the invaders.

Georgian Reconquista

David IV

The Golden Age began with the reign of David IV ("the builder" or "the great"), the son of George II and Queen Helena, who assumed the throne at the age of 16 in a period of Great Turkish Invasions. As he came of age under the guidance of his court minister, George of Chqondidi, David IV suppressed dissent of feudal lords and centralized the power in his hands to effectively deal with foreign threats. In 1121, he decisively defeated much larger Turkish armies during the Battle of Didgori, with fleeing Seljuq Turks being run down by pursuing Georgian cavalry for several days. A huge amount of booty and prisoners were captured by David's army, which had also secured Tbilisi and inaugurated a new era of revival.[6]

To highlight his country's higher status, he became the first Georgian king to reject the highly respected titles bestowed by the Eastern Roman Empire, Georgia’s longtime ally, indicating that Georgia would deal with its powerful friend only on a parity basis. Due to close family ties between Georgian and Byzantine royalty - Princess Martha of Georgia, aunt of David IV, was once a Byzantine Empress Consort - by 11th century as many as 16 Georgian ruling princes and kings had held Byzantine titles, David becoming the last one to do so.[7]

David IV made particular emphasis on removing the vestiges of unwanted eastern influences, which the Georgians considered forced, in favor of the traditional Christian and Byzantine overtones. As part of this effort he founded the Gelati Monastery, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, which became an important center of scholarship in the Eastern Orthodox Christian world of that time.

David also played a personal role in reviving Georgian religious hymnography, composing the Hymns of Repentance (Georgian: გალობანი სინანულისანი, galobani sinanulisani), a sequence of eight free-verse psalms. In this emotional repentance of his sins, David sees himself as reincarnating the Biblical David, with a similar relationship to God and to his people. His hymns also share the idealistic zeal of the contemporaneous European crusaders to whom David was a natural ally in his struggle against the Seljuks.[8]

The reign of Demetrius I and George III

The kingdom continued to flourish under Demetrius I, the son of David. Although his reign saw a disruptive family conflict related to royal succession, Georgia remained a centralized power with a strong military, with several decisive victories against the Muslims in Ganja, gates of which were captured by Demetrius and moved as a trophy to Gelati.

A talented poet, Demetrius also continued his father's contributions to Georgia's religious polyphony. The most famous of his hymns is Thou Art a Vineyard, which is dedicated to Virgin Mary, the patron saint of Georgia, and is still sung in Georgia's churches 900 years after its creation.

Demetrius was succeeded by his son George in 1156, beginning a stage of more offensive foreign policy. The same year he ascended to the throne, George launched a successful campaign against the Seljuq sultanate of Ahlat. He freed the important Armenian town of Dvin from Turkish vassalage and was thus welcomed as a liberator in the area. George also continued the process of intermingling Georgian royalty with the highest ranks of the Eastern Roman Empire, testament of which is the marriage of his daughter Rusudan to Manuel Komnenos, the son of Emperor Andronikos I Komnenos.

Golden age

The Kingdom of Georgia brought about the Georgian Golden Age, which describes a historical period in the High Middle Ages, spanning from roughly the late 11th to 13th centuries, when the kingdom reached the zenith of its power and development. The period saw the flourishing of medieval Georgian architecture, painting and poetry, which was frequently expressed in the development of ecclesiastic art, as well as the creation of first major works of secular literature. It was a period of military, political, economical and cultural progress. It also included the so-called Georgian Renaissance (also called Eastern Renaissance[9]), during which various human activities, forms of craftsmanship and art, such as literature, philosophy and architecture thrived in the kingdom.[10]

Queen Tamar's reign

The successes of his predecessors were built upon by Queen Tamar, daughter of George III, who became the first female ruler of Georgia in her own right and under whose leadership the Georgian state reached the zenith of power and prestige in the Middle Ages. She not only shielded much of her Empire from further Turkish onslaught but successfully pacified internal tensions, including a coup organized by her Russian husband Yury Bogolyubsky, prince of Novgorod. Additionally, she pursued policies that were considered very enlightened for her time period, such as abolishing state-sanctioned death penalty and torture.[11]

Among the remarkable events of Tamar's reign was the foundation of the empire of Trebizond on the Black Sea in 1204. This state was established in the northeast of the crumbling Byzantine Empire with the help of the Georgian armies, which supported Alexios I of Trebizond and his brother, David Komnenos, both of whom were Tamar's relatives.[12] Alexios and David were fugitive Byzantine princes raised at the Georgian court. According to Tamar's historian, the aim of the Georgian expedition to Trebizond was to punish the Byzantine emperor Alexius IV Angelus for his confiscation of a shipment of money from the Georgian queen to the monasteries of Antioch and Mount Athos. Tamar's Pontic endeavor can also be explained by her desire to take advantage of the Western European Fourth Crusade against Constantinople to set up a friendly state in Georgia's immediate southwestern neighborhood, as well as by the dynastic solidarity to the dispossessed Comnenoi.[13][14]

The country's power had grown to such extent that in the later years of Tamar's rule, the Kingdom was primarily concerned with the protection of the Georgian monastic centers in the Holy Land, eight of which were listed in Jerusalem.[15] Saladin's biographer Bahā' ad-Dīn ibn Šaddād reports that, after the Ayyubid conquest of Jerusalem in 1187, Tamar sent envoys to the sultan to request that the confiscated possessions of the Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem be returned. Saladin's response is not recorded, but the queen's efforts seem to have been successful.[16] Ibn Šaddād furthermore claims that Tamar outbid the Byzantine emperor in her efforts to obtain the relics of the True Cross, offering 200,000 gold pieces to Saladin who had taken the relics as booty at the battle of Hattin – to no avail, however.[17]

Jacques de Vitry, the French chronicler and Patriarch of Jerusalem at that time, wrote:[18]

| “ | There is also in the East another Christian people, who are very warlike and valiant in battle, being strong in body and powerful in the countless numbers of their warriors...Being entirely surrounded by infidel nations...these men are called Georgians, because they especially revere and worship St. George...Whenever they come on pilgrimage to the Lord's Sepulchre, they march into the Holy City...without paying tribute to anyone, for the Saracens dare in no wise molest them... | ” |

Nomadic invasions and the gradual decline of Georgia

Around the time when Mongols invaded Slavic northeast of Europe, the nomadic hordes simultaneously pushed down south to Georgia. George IV, son of Queen Tamara, put aside his preparations in support of the Fourth Crusade and concentrated on fighting the invaders, but the Mongol onslaught was too strong to overcome. Georgians suffered heavy losses in the war and the king himself was severely wounded. As a result, George became handicapped and died prematurely at the age of 31.

George's sister Rusudan assumed the throne but she was too inexperienced and her country too weakened to push out the nomads. In 1236 a prominent Mongol commander Chormaqan led a massive army against Georgia and its vassals, forcing Queen Rusudan to flee to the west, leaving eastern Georgia in the hands of noblemen who eventually made peace with the Mongols and agreed to pay tribute; those who resisted were subject to complete annihilation. The Mongol armies chose not to cross the natural barrier of Likhi Range in pursuit of the Georgian Queen, sparing western Georgia of the widespread rampages. Later, Rusudan attempted to gain support from Pope Gregory IX, but without any success. In 1243, Georgia was finally forced to acknowledge the Great Khan as its overlord.

Perhaps no Mongol invasion devastated Georgia as much as the decades of anti-Mongol struggle that took place in the country. The first anti-Mongol uprising started in 1259 under the leadership of David VI and lasted for almost thirty years. The anti-Mongol strife continued without much success under Kings Demetrius the Self-Sacrificer, who was executed by the Mongols, and David VIII.

Georgia finally saw a period of revival unknown since the Mongol invasions under King George V the Brilliant. A far-sighted monarch, George V managed to play on the decline of the Ilkhanate, stopped paying tribute to the Mongols, restored the pre-1220 state borders of Georgia, and returned the Empire of Trebizond into Georgia's sphere of influence. Under him, Georgia established close international commercial ties, mainly with the Byzantine Empire - to which George V had family ties - but also with the great European maritime republics, Genoa and Venice. George V also achieved the restoration of several Georgian monasteries in Jerusalem to the Georgian Orthodox Church and gained free passage for Georgian pilgrims to the Holy Land. The widespread use of the Jerusalem cross in Medieval Georgia - an inspiration for the modern national flag of Georgia - is thought to date to the reign of George V.[19]

Black Death

One of the primary reasons of Georgian political and military decline was the bubonic plague. It was first introduced in 1366 by the soldiers of George the Brilliant returning from a military expedition in south-western Georgia against invading Osmanli tribesmen. It is said that the plague wiped out a large part, if not half of the Georgian populace.[20][21] This further weakened the integrity of the kingdom, as well as its military and logistic capabilities.

Final disintegration

There was a period of reunion and revival under George V the Brilliant (1299–1302, 1314–1346), but the eight onslaughts of the Turco-Mongol conqueror Timur between 1386 and 1403 dealt a great blow to the Georgian kingdom. Its unity was finally shattered and, by 1490/91, the once powerful monarchy fragmented into three independent kingdoms – Kartli (central to eastern Georgia), Kakheti (eastern Georgia), and Imereti (western Georgia) – each led by the rival branches of the Bagrationi dynasty, and into five semi-independent principalities – Odishi (Mingrelia), Guria, Abkhazia, Svaneti, and Samtskhe – dominated by their own feudal clans.

See also

References

- ↑ Paghava, Irakli; Novak, Vlastimil (2013). GEORGIAN COINS IN THE COLLECTION OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM-NÁPRSTEK MUSEUM IN PRAGUE. Retrieved 31 May 2016.

- ↑ Chufrin, Gennadiĭ Illarionovich (2001). The Security of the Caspian Sea Region. Stockholm, Sweden: Oxford University Press. p. 282. ISBN 0199250200.

- ↑ Waters, Christopher P. M. (2013). Counsel in the Caucasus: Professionalization and Law in Georgia. New York City, USA: Springer. p. 24. ISBN 9401756201.

- ↑ Suny, Ronald Grigor (1994). The Making of the Georgian Nation. Bloomington, IN, USA: Indiana University Press. p. 87. ISBN 0253209153.

- ↑ Ronald G. Suny (1996) Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia DIANE Publishing pp. 157-158-160-182

- ↑ (Georgian) Javakhishvili, Ivane (1982), k'art'veli eris istoria (The History of the Georgian Nation), vol. 2, pp. 184-187. Tbilisi State University Press.

- ↑ Cyril Toumanoff. Studies in Christian Caucasian history. Georgetown University Press, 1963. p 202

- ↑ Donald Rayfield, "Davit II", in: Robert B. Pynsent, S. I. Kanikova (1993), Reader's Encyclopedia of Eastern European Literature, p. 82. HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-270007-3.

- ↑ Brisku, Adrian (2013). Bittersweet Europe: Albanian and Georgian Discourses on Europe, 1878-2008. NY, USA: Berghahn Books. p. 134. ISBN 0857459856.

- ↑ van der Zweerde, Evert (2013). Soviet Historiography of Philosophy: Istoriko-Filosofskaja Nauka. Berlin, Germany: Springer Science & Business Media. p. 140. ISBN 9401589437.

- ↑ Machitadze, Zacharia. Mirianashvili, Lado. Lives of the Georgian Saints. St. Herman of Alaska Brotherhood: 2006, p. 167

- ↑ Tamar's paternal aunt was the Comnenoi's grandmother on their father’s side, as it has been conjectured by Cyril Toumanoff(1940).

- ↑ Eastmond (1998), pp. 153–154.

- ↑ Vasiliev (1935), pp. 15–19.

- ↑ Antony Eastmond. Royal Imagery in Medieval Georgia. Penn State Press, 1998. p. 122

- ↑ Pahlitzsch, Johannes, "Georgians and Greeks in Jerusalem (1099–1310)", in Ciggaar & Herman (1996), pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Antony Eastmond. Royal Imagery in Medieval Georgia. Penn State Press, 1998. p. 122-123

- ↑ David Marshall Land. The Lives and Legends of the Georgian Saints. London: Allen & Unwin, 1976, p. 11

- ↑ D. Kldiashvili, History of the Georgian Heraldry, Parlamentis utskebani, 1997, p. 35.

- ↑ IBP, Inc. (2012). Georgia Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Lulu.com. p. 44. ISBN 1438774435.

- ↑ West, Barbara A. (2010). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. New York City, NY, USA: Infobase Publishing. p. 229. ISBN 1438119135.