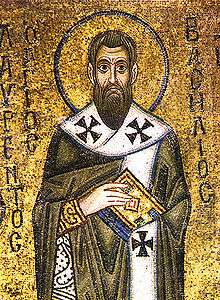

Basil of Caesarea

Basil of Caesarea, also called Saint Basil the Great (Greek: Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας, Ágios Basíleios o Mégas; 329 or 330[6] – January 1 or 2, 379), was the Greek bishop of Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia, Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey). He was an influential theologian who supported the Nicene Creed and opposed the heresies of the early Christian church, fighting against both Arianism and the followers of Apollinaris of Laodicea. His ability to balance his theological convictions with his political connections made Basil a powerful advocate for the Nicene position.

In addition to his work as a theologian, Basil was known for his care of the poor and underprivileged. Basil established guidelines for monastic life which focus on community life, liturgical prayer, and manual labour. Together with Pachomius, he is remembered as a father of communal monasticism in Eastern Christianity. He is considered a saint by the traditions of both Eastern and Western Christianity.

Basil, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa are collectively referred to as the Cappadocian Fathers. The Eastern Orthodox Church and Eastern Catholic Churches have given him, together with Gregory of Nazianzus and John Chrysostom, the title of Great Hierarch. He is recognised as a Doctor of the Church in the Roman Catholic Church. He is sometimes referred to by the epithet "Ουρανοφάντωρ" (Ouranofantor), "revealer of heavenly mysteries".[7]

Life

Early life and education

Basil was born into the wealthy family of Basil the Elder, ,[8] and Emmelia of Caesarea, in Pontus, around 330.[9] His parent were known for their piety.[10] His maternal grandfather was a Christian martyr, executed in the years prior to Constantine I's conversion.[11][12] His pious widow, Macrina, herself a follower of Gregory Thaumaturgus (who had founded the nearby church of Neocaesarea),[13] raised Basil and his four siblings (who also can be venerated as saints): Macrina the Younger, Naucratius, Peter of Sebaste and Gregory of Nyssa.

Basil received more formal education in Caesarea Mazaca in Cappadocia (modern-day Kayseri, Turkey) around 350-51.[14] There he met Gregory of Nazianzus, who would become a lifetime friend.[15] Together, Basil and Gregory went to Constantinople for further studies, including the lectures of Libanius. The two also spent almost six years in Athens starting around 349, where they met a fellow student who would become the emperor Julian the Apostate.[16][17] Basil left Athens in 356, and after travels in Egypt and Syria, he returned to Caesarea, where for around a year he practiced law and taught rhetoric.[18]

Basil's life changed radically after he encountered Eustathius of Sebaste, a charismatic bishop and ascetic.[19] Abandoning his legal and teaching career, Basil devoted his life to God. A letter described his spiritual awakening:

| “ | I had wasted much time on follies and spent nearly all of my youth in vain labors, and devotion to the teachings of a wisdom that God had made foolish. Suddenly, I awoke as out of a deep sleep. I beheld the wonderful light of the Gospel truth, and I recognized the nothingness of the wisdom of the princes of this world.[20] | ” |

Annesi

After his baptism, Basil traveled in 357 to Palestine, Egypt, Syria and Mesopotamia to study ascetics and monasticism.[21][22] He distributed his fortunes among the poor, then went briefly into solitude near Neocaesarea of Pontus (mod. day Niksar, Turkey) on the Iris.[21] Basil eventually realized that while he respected the ascetics' piety and prayerfulness, the solitary life did not call him.[23] Eustathius of Sebaste, a prominent anchorite near Pontus, had mentored Basil. However, they also eventually differed over dogma.[24]

Basil instead felt drawn toward communal religious life, and by 358 he was gathering around him a group of like-minded disciples, including his brother Peter. Together they founded a monastic settlement on his family's estate near Annesi[25] (modern Sonusa or Uluköy, near the confluence of the Iris and Lycos Rivers[26]). His widowed mother Emmelia, sister Macrina and several other women, joined Basil and devoted themselves to pious lives of prayer and charitable works (some claim Macrina founded this community).[27]

Here Basil wrote about monastic communal life. His writings became pivotal in developing monastic traditions of the Eastern Church.[28] In 358, Basil invited his friend Gregory of Nazianzus to join him in Annesi.[29] When Gregory eventually arrived, they collaborated on Origen's Philocalia, a collection of Origen's works .[30] Gregory then decided to return to his family in Nazianzus.

Basil attended the [Council of Constantinople] in 360. He at first sided with Eustathius and the Homoiousians, a semi-Arian faction who taught that the Son was of like substance with the Father, neither the same (one substance) nor different from him.[31] The Homoiousians opposed the Arianism of Eunomius but refused to join with the supporters of the Nicene Creed, who professed that the members of the Trinity were of one substance ("homoousios"). However, Basil's bishop, Dianius of Caesarea, had subscribed only to the earlier Nicene form of agreement. Basil eventually abandoned the Homoiousians, and emerged instead as a strong supporter of the Nicene Creed.[31]

Caesarea

In 362, Bishop Meletius of Antioch ordained Basil as a deacon. Eusebius then summoned Basil to Caesarea and ordained him as presbyter of the Church there in 365. Ecclesiastical entreaties rather than Basil's desires thus altered his career path.[21]

Basil and Gregory Nazianzus spent the next few years combating the Arian heresy, which threatened to divide Cappadocia's Christians. In close fraternal cooperation, they agreed to a great rhetorical contest with accomplished Arian theologians and rhetors.[32] In the subsequent public debates, presided over by agents of Valens, Gregory and Basil emerged triumphant. This success confirmed for both Gregory and Basil that their futures lay in administration of the Church.[32] Basil next took on functional administration of the city of Caesarea.[28] Eusebius is reported as becoming jealous of the reputation and influence which Basil quickly developed, and allowed Basil to return to his earlier solitude. Later, however, Gregory persuaded Basil to return. Basil did so, and became the effective manager of the city for several years, while giving all the credit to Eusebius.

In 370, Eusebius died, and Basil was chosen to succeed him, and was consecrated bishop on June 14, 370.[33] His new post as bishop of Caesarea also gave him the powers of exarch of Pontus and metropolitan of five suffragan bishops, many of whom had opposed him in the election for Eusebius's successor. It was then that his great powers were called into action. Hot-blooded and somewhat imperious, Basil was also generous and sympathetic. He personally organized a soup kitchen and distributed food to the poor during a famine following a drought. He gave away his personal family inheritance to benefit the poor of his diocese.

His letters show that he actively worked to reform thieves and prostitutes. They also show him encouraging his clergy not to be tempted by wealth or the comparatively easy life of a priest, and that he personally took care in selecting worthy candidates for holy orders. He also had the courage to criticize public officials who failed in their duty of administering justice. At the same time, he preached every morning and evening in his own church to large congregations. In addition to all the above, he built a large complex just outside Caesarea, called the Basiliad,[34] which included a poorhouse, hospice, and hospital, and was compared by Gregory of Nazianzus to the wonders of the world.[35]

His zeal for orthodoxy did not blind him to what was good in an opponent; and for the sake of peace and charity he was content to waive the use of orthodox terminology when it could be surrendered without a sacrifice of truth. The Emperor Valens, who was an adherent of the Arian philosophy, sent his prefect Modestus to at least agree to a compromise with the Arian faction. Basil's adamant negative response prompted Modestus to say that no one had ever spoken to him in that way before. Basil replied, "Perhaps you have never yet had to deal with a bishop." Modestus reported back to Valens that he believed nothing short of violence would avail against Basil. Valens was apparently unwilling to engage in violence. He did however issue orders banishing Basil repeatedly, none of which succeeded. Valens came himself to attend when Basil celebrated the Divine Liturgy on the Feast of the Theophany (Epiphany), and at that time was so impressed by Basil that he donated to him some land for the building of the Basiliad. This interaction helped to define the limits of governmental power over the church.[36]

Basil then had to face the growing spread of Arianism. This belief system, which denied that Christ was consubstantial with the Father, was quickly gaining adherents and was seen by many, particularly those in Alexandria most familiar with it, as posing a threat to the unity of the church.[37] Basil entered into connections with the West, and with the help of Athanasius, he tried to overcome its distrustful attitude toward the Homoiousians. The difficulties had been enhanced by bringing in the question as to the essence of the Holy Spirit. Although Basil advocated objectively the consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son, he belonged to those, who, faithful to Eastern tradition, would not allow the predicate homoousios to the former; for this he was reproached as early as 371 by the Orthodox zealots among the monks, and Athanasius defended him. He maintained a relationship with Eustathius despite dogmatic differences.

Basil corresponded with Pope Damasus in the hope of having the Roman bishop condemn heresy wherever found, both East and West. The pope's apparent indifference upset Basil's zeal and he turned around in distress and sadness.

Death and legacy

Basil died before the factional disturbances ended. He suffered from liver disease; excessive ascetic practices also contributed to his early demise. Historians disagree about the exact date Basil died.[38] The great institute before the gates of Caesarea, the Ptochoptopheion, or "Basileiad", which was used as poorhouse, hospital, and hospice became a lasting monument of Basil's episcopal care for the poor.[24]

Writings

The principal theological writings of Basil are his On the Holy Spirit, a lucid and edifying appeal to Scripture and early Christian tradition (to prove the divinity of the Holy Spirit), and his Refutation of the Apology of the Impious Eunomius, written about in 364, three books against Eunomius of Cyzicus, the chief exponent of Anomoian Arianism. The first three books of the Refutation are his work; his authorship of the fourth and fifth books is generally considered doubtful.[39]

He was a famous preacher, and many of his homilies, including a series of Lenten lectures on the Hexaëmeron (also Hexaëmeros, "Six Days of Creation"; Latin: Hexameron), and an exposition of the psalter, have been preserved. Some, like that against usury and that on the famine in 368, are valuable for the history of morals; others illustrate the honor paid to martyrs and relics; the address to young men on the study of classical literature shows that Basil was lastingly influenced by his own education, which taught him to appreciate the propaedeutic importance of the classics.[40]

In his exegesis Basil was a great admirer of Origen and the need for the spiritual interpretation of Scripture. In his work on the Holy Spirit, he asserts that "to take the literal sense and stop there, is to have the heart covered by the veil of Jewish literalism. Lamps are useless when the sun is shining." He frequently stresses the need for Reserve in doctrinal and sacramental matters. At the same time he was against the wild allegories of some contemporaries. Concerning this, he wrote:

"I know the laws of allegory, though less by myself than from the works of others. There are those, truly, who do not admit the common sense of the Scriptures, for whom water is not water, but some other nature, who see in a plant, in a fish, what their fancy wishes, who change the nature of reptiles and of wild beasts to suit their allegories, like the interpreters of dreams who explain visions in sleep to make them serve their own end."[41]

His ascetic tendencies are exhibited in the Moralia and Asketika (sometimes mistranslated as Rules of St. Basil), ethical manuals for use in the world and the cloister, respectively. There has been a good deal of discussion concerning the authenticity of the two works known as the Greater Asketikon and the Lesser Asketikon.[24]

It is in the ethical manuals and moral sermons that the practical aspects of his theoretical theology are illustrated. So, for example, it is in his Sermon to the Lazicans that we find St. Basil explaining how it is our common nature that obliges us to treat our neighbor's natural needs (e.g., hunger, thirst) as our own, even though he is a separate individual.

His three hundred letters reveal a rich and observant nature, which, despite the troubles of ill-health and ecclesiastical unrest, remained optimistic, tender and even playful. His principal efforts as a reformer were directed towards the improvement of the liturgy, and the reformation of the monastic institutions of the East.

Most of his extant works, and a few spuriously attributed to him, are available in the Patrologia Graeca, which includes Latin translations of varying quality. Several of St. Basil's works have appeared in the late twentieth century in the Sources Chrétiennes collection.

Liturgical contributions

Saint Basil of Caesarea holds a very important place in the history of Christian liturgy, coming as he did at the end of the age of persecution. Basil's liturgical influence is well attested in early sources. Though it is difficult at this time to know exactly which parts of the Divine Liturgies which bear his name are actually his work, a vast corpus of prayers attributed to him has survived in the various Eastern Christian churches. Tradition also credits Basil with the elevation of the iconostasis to its present height.

Most of the liturgies bearing the name of Basil are not entirely his work in their present form, but they nevertheless preserve a recollection of Basil's activity in this field in formularizing liturgical prayers and promoting church-song. Patristics scholars conclude that the Liturgy of Saint Basil "bears, unmistakably, the personal hand, pen, mind and heart of St. Basil the Great."[42]

One liturgy that can be attributed to him is The Divine Liturgy of Saint Basil the Great, a liturgy that is somewhat longer than the more commonly used Divine Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom. The difference between the two is primarily in the silent prayers said by the priest, and in the use of the hymn to the Theotokos, All of Creation, instead of the Axion Estin of Saint John Chrysostom's Liturgy. Chrysostom's Liturgy has come to replace Saint Basil's on most days in the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic liturgical traditions. However, they still use Saint Basil's Liturgy on certain feast days: the first five Sundays of Great Lent, the Eves of Nativity and Theophany, on Great and Holy Thursday and Holy Saturday and on the Feast of Saint Basil, January 1 (for those churches which follow the Julian Calendar, their January 1 falls on January 14 of the Gregorian Calendar).

The Eastern Churches preserve numerous other prayers attributed to Saint Basil, including three Prayers of Exorcism, several Morning and Evening Prayers, the "Prayer of the Hours" which is read at each service of the Daily Office, and the "Kneeling Prayers" which are recited by the priest at Vespers on Pentecost in the Byzantine Rite.

Influence on Monasticism

Through his examples and teachings St. Basil effected a noteworthy moderation in the austere practices which were previously characteristic of monastic life.[43] He is also credited with coordinating the duties of work and prayer to ensure a proper balance between the two.[44]

St. Basil is remembered as one of the most influential figures in the development of Christian monasticism. Not only is Basil recognized as the father of Eastern monasticism; historians recognize that his legacy extends also to the Western church, largely due to his influence on Saint Benedict.[45] Patristic scholars such as Meredith assert that Benedict himself recognized this when he wrote in the epilogue to his Rule that his monks, in addition to the Bible, should read "the confessions of the Fathers and their institutes and their lives and the Rule of our Holy Father, Basil.[46] Basil's teachings on monasticism, as encoded in works such as his Small Asketikon, was transmitted to the west via Rufinus during the last 4th century.[47]

As a result of his influence, numerous religious orders in Eastern Christianity bear his name. In the Roman Catholic Church, the Basilian Fathers, also known as The Congregation of St. Basil, an international order of priests and students studying for the priesthood, is named after him.

Commemorations

St Basil was given the title Doctor of the Church in the Western Church for his contributions to the debate initiated by the Arian controversy regarding the nature of the Trinity, and especially the question of the divinity of the Holy Spirit. Basil was responsible for defining the terms "ousia" (essence/substance) and "hypostasis" (person/reality), and for defining the classic formulation of three Persons in one Nature. His single greatest contribution was his insistence on the divinity and consubstantiality of the Holy Spirit with the Father and the Son.

In Greek tradition, he brings gifts to children every January 1 (St Basil's Day). It is traditional on St Basil's Day to serve vasilopita, a rich bread baked with a coin inside. It is customary on his feast day to visit the homes of friends and relatives, to sing New Year's carols, and to set an extra place at the table for Saint Basil. Basil, being born into a wealthy family, gave away all his possessions to the poor, the underprivileged, those in need, and children.[48]

According to some sources, Saint Basil died on January 1, and the Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates his feast day together with that of the Feast of the Circumcision on that day. This was also the day on which the General Roman Calendar celebrated it at first; but in the 13th century it was moved to June 14, a date believed to be that of his ordination as bishop, and it remained on that date until the 1969 revision of the calendar, which moved it to January 2, rather than January 1, because the latter date is occupied by the Solemnity of Mary, Mother of God. On January 2 Saint Basil is celebrated together with Saint Gregory Nazianzen.[49] Some traditionalist Catholics continue to observe pre-1970 calendars.

The Lutheran Church Missouri Synod commemorates Basil, along with Gregory of Nazianzus and Gregory of Nyssa on January 10.

The Church of England celebrates Saint Basil's feast on January 2, but the Episcopal Church and the Anglican Church of Canada celebrate it on June 14.[50]

In the Byzantine Rite, January 30 is the Synaxis of the Three Holy Hierarchs, in honor of Saint Basil, Saint Gregory the Theologian and Saint John Chrysostom.

The Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria celebrates the feast day of Saint Basil on the 6th of Tobi (6th of Terr on the Ethiopian calendar of the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church). At present, this corresponds to January 14, January 15 during leap year.

There are numerous relics of Saint Basil throughout the world. One of the most important is his head, which is preserved to this day at the monastery of the Great Lavra on Mount Athos in Greece. The mythical sword Durandal is said to contain some of Basil's blood.[51]

See also

- List of Orthodox saints

- List of Catholic saints

- Cappadocian Fathers

- Gregory of Nyssa

- Gregory Nazianzus

- John Chrysostom

- Basilian monk

- Vasilopita

- Christian mystics

References

- ↑ Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Ὁ Ἅγιος Βασίλειος ὁ Μέγας ὁ Καππαδόκης. 1 Ιανουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ St Basil the Great the Archbishop of Caesarea, in Cappadocia. OCA - Feasts and Saints.

- ↑ Great Synaxaristes: (Greek) Οἱ Ἅγιοι Τρεῖς Ἱεράρχες. 30 Ιανουαρίου. ΜΕΓΑΣ ΣΥΝΑΞΑΡΙΣΤΗΣ.

- ↑ Synaxis of the Ecumenical Teachers and Hierarchs: Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom. OCA - Feasts and Saints.

- ↑ Lutheranism 101, CPH, St. Louis, 2010, p.277

- ↑ Fedwick (1981), p. 5

- ↑ "St Basil the Great the Archbishop of Caesarea, in Cappadocia". Orthodox Church in America Website. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ Quasten(1986), p. 204.

- ↑ Bowersock et al. (1999), p.336

- ↑ Oratio 43.4, PG 36. 500B, tr. p.30, as presented in Rousseau (1994), p.4.

- ↑ Davies (1991), p. 12.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), p. 4.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), p. 12 & p. 4 respectively

- ↑ Hildebrand (2007), p. 19.

- ↑ Norris, Frederick (1997). "Basil of Caesarea". In Ferguson, Everett. The Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (second edition). New York: Garland Press.

- ↑ Ruether (1969), pp. 19, 25.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), pp. 32–40.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), p. 1.

- ↑ Hildebrand (2007), pp. 19–20.

- ↑ Basil, Ep. 223, 2, as quoted in Quasten (1986), p. 205.

- 1 2 3 Quasten (1986), p. 205.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.) vol. 1, p. 938.

- ↑ Merredith (1995), p. 21.

- 1 2 3 McSorley, Joseph. "St. Basil the Great." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 31 May 2016

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica (15th ed.) vol. 1, p. 938.

- ↑ mod. Yeşilırmak and Kelkit Çayi rivers, see Rousseau (1994), p. 62.

- ↑ The New Westminster Dictionary of Church History: The Early, Medieval, and Reformation Eras, vol.1, Westminster John Knox Press, 2008, ISBN 0-664-22416-4, p. 75.

- 1 2 Attwater, Donald and Catherine Rachel John. The Penguin Dictionary of Saints. 3rd edition. New York: Penguin Books, 1993. ISBN 0-14-051312-4.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), p. 66.

- ↑ Merredith (1995), pp. 21–22.

- 1 2 Meredith (1995), p. 22.

- 1 2 McGuckin (2001), p. 143.

- ↑ Meredith (1995), p. 23

- ↑ The Living Age. 48. Littell, Son and Company. 1856. p. 326.

- ↑ Gregory of Nazianzus. Oration 43: Funeral Oration on the Great S. Basil, Bishop of Cæsarea in Cappadocia. p. 63. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ Alban Butler; Paul Burns (1995). Butler's Lives of the Saints. 1. A&C Black,. p. 14.

- ↑ Foley, O.F.M., Leonard (2003). "St. Basil the Great (329-379)". In McCloskey, O.F.M., Pat (rev.). Saint of the Day: Lives, Lessons and Feasts (5th Revised Edition). Cincinnati, Ohio: St. Anthony Messenger Press. ISBN 0-86716-535-9. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ Rousseau (1994), pp. 360–363, Appendix III: The Date of Basil's Death and of the Hexaemeron

- ↑ Jackson, Blomfield. "Basil: Letters and Select Works", Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, (Philip Schaff and Henry Wace, eds.) .T&T Clark, Edinburough

- ↑ Deferrari, Roy J. "The Classics and the Greek Writers of the Early Church: Saint Basil." The Classical Journal Vol. 13, No. 8 (May, 1918). 579–91.

- ↑ Basil. "Hexameron, 9.1". In Schaff, Philip. Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers (2nd Series). 8 Basil: Letters and Select Works. Edinburgh: T&T Clark (1895). p. 102. Retrieved 2007-12-15.. Cf. Hexameron, 3.9 (Ibid., pp. 70-71).

- ↑ Bebis (1997), p. 283

- ↑ Murphy (1930), p. 94.

- ↑ Murphy (1930), p. 95.

- ↑ See K. E. Kirk, The Vision of God: The Christian Document of the summum bonum (London, 1931), 9.118, (as quoted in Meredith)

- ↑ Meredith (1995), p.24

- ↑ Silvas (2002), pp. 247-259, in Vigliae Christanae

- ↑ "Santa Claus". Eastern-Orthodoxy.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2008. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ Calendarium Romanum, Libreria Editrice Vaticana 1969, p. 84

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 2013-11-03.

- ↑ Keary (1882), p. 512

Bibliography

- Basil of Caesarea, Hexaemeron, London, 2013. limovia.net ISBN 9781783362110 (digital version – ebook)

- Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, trans. David Anderson (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1980)

- Basil the Great, On Social Justice, trans. C. Paul Schroeder (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir's Seminary Press, 2009)

- Basil the Great, Address to Young Men On Greek Literature, trans. Edward R. Maloney (New York: American Book Company, 1901)

- Bebis, George (Fall–Winter 1997). "Introduction to the Liturgical Theology of St Basil the Great". Greek Orthodox Theological Review. 42 (3-4): 273–285. ISSN 0017-3894.

- Paul Jonathan Fedwick, ed. (1981). Basil of Caesarea, christian, humanist, ascetic: a sixteen-hundredth anniversary symposium, Part 1. Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies. ISBN 978-0-88844-412-7.

- Bibliotheca Basiliana Universalis, A Study of the Manuscript Tradition of the Works of Basil of Caesarea Part 1 year=1981 Part II,1 year=1996 PartII,2 year=1996 Part III year=1997 Part IV,1 year=1999 Part IV,2 year=1999 publisher= Brepols editor=Paul Jonathan Fedwick

- Bowersock, Glen Warren; Brown, Peter; Grabar, Oleg, eds. (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-67451-173-6.

- The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition, v. 1. London: Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Hildebrand, Stephen M. (2007). The Trinitarian Theology of Basil of Caesarea. Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1473-3.

- Keary, Charles Francis (1882). Outline of Primitive Belief Among the Indo-European Races. New York: C. Scribner's Sons.

- Meredith, Anthony (1995). The Cappadocians. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminar Press. ISBN 0-88141-112-4.

- Migne, Jacques Paul (ed.) (1857–1866). Cursus Completus Patrologiae Graecae. Paris: Imprimerie Catholique.

- Murphy, Margaret Gertrude (1930). St. Basil and Monasticism: Catholic University of America Series on Patristic Studies, Vol. XXV. New York: AMS Press. ISBN 0-404-04543-X.

- Rousseau, Phillip (1994). Basil of Caesarea. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-08238-9.

- Quasten, Johannes (1986). Patrology, v.3. Christian Classics. ISBN 0-87061-086-4.

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford (1969). Gregory of Nazianzus. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Silvas, Anna M. (September 2002). "Edessa to Cassino: The Passage of Basil's Asketikon to the West". Vigliae Christianae. Brill Academic. 56 (3): 247–259. doi:10.1163/157007202760235382. ISSN 0042-6032.

- Corona, Gabriella, ed. (2006). Aelfric's Life of Saint Basil the Great: Background and Content. Cambridge: D.S. Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84384-095-4.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). "article name needed". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). "article name needed". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

Further reading

- St. Basil the Great, On the Holy Spirit, London, 2012. limovia.net ISBN 978-1-78336-002-4.

- Karahan, Anne. "Beauty in the Eyes of God. Byzantine Aesthetics and Basil of Caesarea", in: Byzantion. Revue Internationale des Études Byzantines 82 (2012): 165-212.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Basil of Caesarea |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Basil of Caesarea. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Basil of Caesarea. |

- Christian Classics Ethereal Library, Early Church Fathers, Series II, Vol. VIII contains the treatise On the Holy Spirit, the Hexaemeron, some of the homilies and the letters

- St. Basil the Great in English and Greek, Select Resources

- Basil the Great article from Orthodox Wikipedia has a slightly longer article on St. Basil

- The Heritage of the Holy Fathers has a more complete collection of his homilies (and some other works, but only a few of his letters)—in Russian

- American Catholic: St. Basil the Great

- St. Basil the Great the Archbishop of Caesarea, in Cappadocia Orthodox icon and synaxarion

- St. Basil's Sermons About Fasting, translated by Kent Berghuis

- St. Basil at the Christian Iconography web site.

- Works by or about Basil of Caesarea at Internet Archive

- Works by Basil of Caesarea at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Literature by and about Basil of Caesarea in the German National Library catalogue

- Works by and about Basil of Caesarea in the Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek (German Digital Library)

- Basil of Caesarea in the Ecumenical Lexicon of Saints