National epic

A national epic is an epic poem or a literary work of epic scope which seeks or is believed to capture and express the essence or spirit of a particular nation; not necessarily a nation state, but at least an ethnic or linguistic group with aspirations to independence or autonomy. National epics frequently recount the origin of a nation, a part of its history, or a crucial event in the development of national identity such as other national symbols. In a broader sense, a national epic may simply be an epic in the national language which the people or government of that nation are particularly proud of. It is distinct from a pan-national epic which is taken as representative of a larger cultural or linguistic group than a nation or a nation-state.

History

In medieval times Homer's Iliad was taken to be based on historical facts, and the Trojan War came to be considered as seminal in the genealogies of European monarchies.[1] Virgil's Aeneid was taken to be the Roman equivalent of the Iliad, starting from the Fall of Troy and leading up to the birth of the young Roman nation. According to the then prevailing conception of history, empires were born and died in organic succession and correspondences existed between the past and the present. Geoffrey of Monmouth's 12th century classically inspired Historia Regum Britanniae, for example, fulfilled this function for the British or Welsh. Just as kings longed to emulate great leaders of the past, Alexander or Caesar, it was a temptation for poets to become a new Homer or Virgil. In 16th century Portugal, Luis de Camões celebrated Portugal as a naval power in his Os Lusíadas while Pierre de Ronsard set out to write La Franciade, an epic meant to be the Gallic equivalent of Virgil's poem that also traced back France's ancestry to Trojan princes.[2]

The emergence of a national ethos, however, preceded the coining of the phrase national epic, which seems to originate with Romantic nationalism. Where no obvious national epic existed, the "Romantic spirit" was motivated to fill it. An early example of poetry that was invented to fill a perceived gap in "national" myth is Ossian, the narrator and supposed author of a cycle of poems by James Macpherson, which Macpherson claimed to have translated from ancient sources in Scottish Gaelic. However, many national epics (including Macpherson's Ossian) antedate 19th-century romanticism.

In the early 20th century, the phrase no longer necessarily applies to an epic poem, and occurs to describe a literary work that readers and critics agree is emblematical of the literature of a nation, without necessarily including details from that nation's historical background. In this context the phrase has definitely positive connotations, as for example in James Joyce's Ulysses where it is suggested Don Quixote is Spain's national epic while Ireland's remains as yet unwritten:

They remind one of Don Quixote and Sancho Panza. Our national epic has yet to be written, Dr Sigerson says. Moore is the man for it. A knight of the rueful countenance here in Dublin.[3]

Poetic epics

Examples of epics that have been enlisted as "national" include:

Africa

- Ethiopia – Kebra Nagast

- Mali – Epic of Sundiata

- Nigeria –

Americas

- Argentina –

- Brazil –

- Chile– La Araucana/The Araucaniad by Alonso de Ercilla y Zuñiga

- United States–

- The Song of Hiawatha by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow[4][5]

- Evangeline by Longfellow (shared with Canada)

- Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman[6][7]

- Uruguay–

- La Leyenda Patria by Juan Zorrilla de San Martín

- Venezuela–

Asia

- Cambodia – Reamker

- Georgia – The Knight in the Panther's Skin by Shota Rustaveli

- Indian subcontinent

- India / Nepal / Bhutan / Ancient Hindus

- Pakistan

- Sri Lanka

- Iran and Persian speakers

- Shahnameh (legends and history of Iran from earliest times to the end of the Sassanid Empire)

- Book of the Deeds of Ardeshir, Son of Papak (Epic story that narrates the story of Ardashir I)

- Amir Arsalan

- Iraq / Babylonians / Mesopotamia – Epic of Gilgamesh

- Indonesia

- Israel / Hebrews – Book of Job (and other poetic sections of the Tanakh, i.e. the Hebrew Bible)

- Japan

- The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Taketori Monogatari)

- The Tale of the Heike (Heike Monogatari)

- Kipchaks (e.g. in Tatarstan) – Chora Batir

- Korea

- Jewang Ungi by Yi Seung-hyu

- Kyrgyz people – Epic of Manas

- Laos – Phra Lak Phra Lam

- Malaysia –

- Mongols (Kalmyks and Oirats) – Epic of Jangar

- Myanmar – Yama Zatdaw

- Philippines –

- Tibet – Epic of King Gesar

- Thailand – Ramakien

- Vietnam –

Europe

- Albania – Lahuta e Malcís (The Highland Lute) by Gjergj Fishta

- Ancient Rome – Aeneid by Virgil

- Armenia – Daredevils of Sassoun (also known as "Sasuntsi Davit" after its main character, David of Sasun)

- Belgium / Flanders – De Leeuw van Vlaanderen ("The Lion of Flanders")

- Bulgaria –

- Епопея на Забравените (Epic of the Forgotten) by Ivan Vazov

- Catalonia – L'Atlàntida (1877) and Canigó (1886) by Jacint Verdaguer

- Croatia –

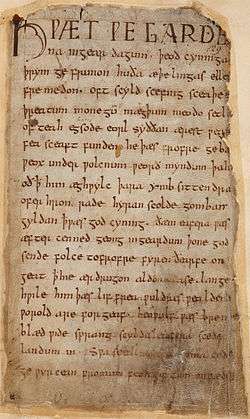

- England

- Estonia – Kalevipoeg by Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald

- Europe and Western civilization generally –

- Finland – Kalevala by Elias Lönnrot

- France – La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland) about Roland/Orlando.

- Georgia – The Knight in the Panther's Skin by Shota Rustaveli

- Germany – Nibelungenlied

- Greece, Ancient (Hellas and Mediterranean Greek colonies) – Iliad and Odyssey by Homer

- Greece (Byzantine Empire) – Digenes Akritas

- Hungary – Siege of Sziget (Szigeti Veszedelem) by Miklós Zrínyi

- Iceland – The Poetic Edda

- Ireland

- Italy –

- Latvia – Lāčplēsis by Andrejs Pumpurs

- Lithuania – The Seasons by Kristijonas Donelaitis

- Luxembourg – Rénert the Fox by Michel Rodange

- Portugal –

- Os Lusíadas ("The Lusiads") by Luís de Camões[8]

- Message by Fernando Pessoa

- Poland – Pan Tadeusz by Adam Mickiewicz

- Romania – Miorița

- Scotland –

- Serbia and Montenegro – The Mountain Wreath by Petar II Petrović-Njegoš (Serbian epic poetry)

- Slovakia -

- Svatopluk by Ján Hollý

- Slávy Dcera by Ján Kollár

- Slovenia – The Baptism on the Savica, by France Prešeren

- Spain –

- Cantar de Mio Cid

- Mocedades de Rodrigo

- La Araucana by Alonso de Ercilla (shared with Chile)

- Udmurts – Dorvyzhy

Prose epics

Some prose works, while not strictly epic poetry, have an important place in the national consciousness of their nations. These include the following:

- Arabs – Arabian Nights

- Argentina –

- Britain –

- Canada –

- Catalonia –

- Gesta comitum Barcinonensium

- The Four Great Chronicles:

- Llibre dels fets by James I of Aragon

- Crònica by Bernat Desclot

- Crònica de Ramon Muntaner

- Crònica de Pere el Cerimoniós by Peter IV of Aragon

- Tirant lo Blanch, an epic romance, one of the best works of Catalan medieval literature.

- Chile

- Martin Rivas by Alberto Blest Gana, a 19th Century Social Realist Romance novel on the Chilean revolution of the 1850s

- China

- Colombia –

- Cien Años de Soledad, (One Hundred Years of Solitude) a contemporary novel that parallels Colombian history in the fictional town of Macondo.

- La Vorágine, (The Vortex) a contemporary novel with prosaic poetic interuldes that depicts life in the great pastures, the immensity and overwhelming nature of the Amazon jungle and the appalling conditions under which workers in rubber factories toil.

- En la diestra de Dios padre, (At God's Right Side) a costumbrist novel depicting life and culture in the Paisa Region

- María, a costumbrist novel.

- Denmark – Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus (the main inspiration to Hamlet by Shakespeare)

- Ecuador

- Cumandá Romantico national novel written by Juan León Mera

- Egypt / Ancient Egyptians – Story of Sinuhe

- England –

- Ethiopia – Kebra Nagast

- Flanders (Dutch-speaking part of Belgium) –

- De Leeuw van Vlaanderen ("The Lion of Flanders")

- France

- Historia Francorum

- Les Misérables (a novel spanning a crucial era of French history)

- Georgia

- Germany – The Sorrows of Young Werther (a widely influential epistolary tragic novel)

- Guatemala and Mexico-

- Scandinavia and Iceland – The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson

- Iceland - Njáls saga

- Ireland

- Táin Bó Cúailnge (Prose narration with poetic interludes)

- Ulysses (20th century adaptation of Homer's Odyssey by James Joyce)

- Israel / Hebrews – Book of Exodus (along with rest of the Tanakh, i.e. the Hebrew Bible; especially the Torah)

- Italy –

- Italy –

- Japan –

- The Tale of Genji (Genji Monogatari) by Murasaki Shikibu

- Korea – Samguk Yusa (prose with songs)

- Lithuania – Anykščių šilelis by Antanas Baranauskas

- Mayans – Popol Vuh

- Mexico

- Visión de Anáhuac by Alfonso Reyes

- Estas ruinas que ves by Jorge Ibargüengoitia

- Clemencia by Ignacio Manuel Altamirano

- La muerte del tigre by Rosario Castellanos

- El éxodo y las flores del camino by Amado Nervo

- Gringo viejo by Carlos Fuentes

- Mongolia –

- Borte Chino

- The Secret History of the Mongols (Genghis Khan's biography)

- Netherlands

- Van den vos Reynaerde – (The local Netherlandic tale about the trickster fox Reynard) by an anonymous 13th century Dutch writer)

- Max Havelaar – Multatuli

- De avonden – Gerard Reve

- Norway – Heimskringla by Snorri Sturluson

- Poland

- Portugal – Peregrinação (see Fernão Mendes Pinto)

- Philippines

- Russia –

- Scotland –

- Spain –

- Sweden – The Emigrant Cycle

- Switzerland – William Tell

- Tatar – "Chora Batir"[9]

- Turkic peoples –

- Alpamysh[10] (all Central Asia)

- Book of Dede Korkut (Oghuz nations: Azerbaijan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Turcomans of Iraq, as well as Central Asia and other Turkic nations)

- Oghuz-nameh (Oghuz nations: Azerbaijan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Turcomans of Iraq)

- Ergenekon legend (Turkey)

- Koroglu (Azerbaijan and Turkey)

- Kutadgu Bilig (Central Asia, Uighurs and other Turkic nations)

- United States –

- Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by American satirist Mark Twain

- Moby-Dick, the 19th century classic novel by Herman Melville

- Venezuela – Doña Bárbara by Romulo Gallegos, a novel detailing the struggle between civilization and barbarism in early 20th century, as well as a psychological study of the Venezuelan plainsmen.

- Wales – Mabinogion

See also

- Civil religion

- Epic film

- Epic poetry

- Founding myth

- Great American Novel

- List of national poets

- List of world folk-epics

- National myth

- Philippe-Alexandre Le Brun de Charmettes

References

- ↑ Paul Cohen, "In search of the Trojan Origins of French", in Fantasies of Troy, Classical Tales and the Social Imaginary in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, Alan Shepard, Stephen David Powell eds., published by the Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies, 2004, p. 65 sq., ISBN 0-7727-2025-8. "Like many of their counterparts across Europe, seventh-century scholars in France had invented a myth of the Trojan origins of Gaul" (p. 67)

- ↑ Epic(French) Liliane Kesteloot, University of Dakar

- ↑ James Joyce. Ulysses, Vintage Books, New York, 1961, 189 (p.192)

- ↑ Tappan, Lucy (1896). Topical notes on American authors. University of California Libraries. p. 209. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

American's national epic poem.

- ↑ Trachtenberg, Alan (2004). Shades of Hiawatha: Staging Indians, Making Americans, 1880-1930. Hill and Wang. p. 61. ISBN 978-0374299750. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

A 'national folk epic' writes a recent commentator...

- ↑ Maureen N. McLane (July 31, 2005). "An American epic". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

Walt Whitman published the first edition of 'Leaves of Grass,' the book, including 'Song of Myself,' that more than any other has a claim to be our national epic

- ↑ Bloom, Harold; McGowan, Tony, eds. (2007). Herman Melville. Bloom's Classic Critical Views. Chelsea House Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 978-0791095577. Retrieved March 6, 2015.

How shall we judge Melville's total achievement, at its best? There is Moby-Dick, only (though defeated) rival to Leaves of Grass as our national epic...

- ↑ "The Lusiads". World Digital Library. 1800–1882. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑

- ↑