Paradise Lost

Title page of the first edition (1667) | |

| Author | John Milton |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | J. B. de Medina and Henry Aldrich |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Epic poetry, Christian mythology |

| Publisher | Samuel Simmons (original) |

Publication date | 1667 |

| Media type | |

| Followed by | Paradise Regained |

| Text | Paradise Lost at Wikisource |

Paradise Lost is an epic poem in blank verse by the 17th-century English poet John Milton (1608–1674). The first version, published in 1667, consisted of ten books with over ten thousand lines of verse. A second edition followed in 1674, arranged into twelve books (in the manner of Virgil's Aeneid) with minor revisions throughout and a note on the versification.[1] It is considered by critics to be Milton's major work, and it helped solidify his reputation as one of the greatest English poets of his time.[2]

The poem concerns the Biblical story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book I, is to "justify the ways of God to men".[3]

Composition

In his introduction to the Penguin edition of Paradise Lost, the Milton scholar John Leonard notes, "John Milton was nearly sixty when he published Paradise Lost in 1667. [The writer] John Aubrey (1626–97) tells us that the poem was begun in about 1658 and finished in about 1663. But parts were almost certainly written earlier, and its roots lie in Milton's earliest youth."[6] Leonard speculates that the English Civil War interrupted Milton's earliest attempts to start his "epic [poem] that would encompass all space and time."[6]

Leonard also notes that Milton "did not at first plan to write a biblical epic."[6] Since epics were typically written about heroic kings and queens (and with pagan gods), Milton originally envisioned his epic to be based on a legendary Saxon or British king like the legend of King Arthur.[7][8]In the 1667 version of Paradise Lost, the poem was divided into ten books. However, in the 1672 edition, Paradise Lost contained twelve books.[9]

Having gone totally blind in 1652, Milton wrote Paradise Lost entirely through dictation with the help of amanuenses and friends. He also wrote the epic poem while he was often ill, suffering from gout, and despite the fact that he was suffering emotionally after the early death of his second wife, Katherine Woodcock, in 1658, and the death of their infant daughter (though Milton remarried soon after in 1663).[10]

Synopsis

The poem is separated into twelve "books" or sections, the lengths of which vary greatly (the longest is Book IX, with 1,189 lines, and the shortest Book VII, with 640). The Arguments at the head of each book were added in subsequent imprints of the first edition. Originally published in ten books, a fully "Revised and Augmented" edition reorganized into twelve books was issued in 1674, and this is the edition generally used today.[11]

The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being recounted later.

Milton's story has two narrative arcs, one about Satan (Lucifer) and the other following Adam and Eve. It begins after Satan and the other rebel angels have been defeated and banished to Hell, or, as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pandæmonium, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organise his followers; he is aided by Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers to poison the newly created Earth and God's new and most favoured creation, Mankind. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas. After an arduous traversal of the Chaos outside Hell, he enters God's new material World, and later the Garden of Eden.

At several points in the poem, an Angelic War over Heaven is recounted from different perspectives. Satan's rebellion follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. The battles between the faithful angels and Satan's forces take place over three days. At the final battle, the Son of God single-handedly defeats the entire legion of angelic rebels and banishes them from Heaven. Following this purge, God creates the World, culminating in his creation of Adam and Eve. While God gave Adam and Eve total freedom and power to rule over all creation, he gave them one explicit command: not to eat from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil on penalty of death.

The story of Adam and Eve's temptation and fall is a fundamentally different, new kind of epic: a domestic one. Adam and Eve are presented as having a full relationship while still being without sin. They have passions and distinct personalities. Satan, disguised in the form of a serpent, successfully tempts Eve to eat from the Tree by preying on her vanity and tricking her with rhetoric. Adam, learning that Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same sin. He declares to Eve that since she was made from his flesh, they are bound to one another ‒ if she dies, he must also die. In this manner, Milton portrays Adam as a heroic figure, but also as a greater sinner than Eve, as he is aware that what he is doing is wrong.

After eating the fruit, Adam and Eve have lustful sex. At first, Adam is convinced that Eve was right in thinking that eating the fruit would be beneficial. However, they soon fall asleep and have terrible nightmares, and after they awake, they experience guilt and shame for the first time. Realizing that they have committed a terrible act against God, they engage in mutual recrimination.

Meanwhile, Satan returns triumphantly to Hell, amidst the praise of his fellow fallen angels. He tells them about how their scheme worked and human kind has fallen, giving them complete dominion over Paradise. As he finishes his speech, however, the fallen angels around him become hideous snakes, and soon enough, Satan himself turned into a snake, deprived of limbs and unable to talk. Thus, they share the same punishment, as they shared the same guilt.

Eve appeals to Adam for reconciliation of their actions. Her encouragement enables them to approach God, and sue for grace, bowing on suppliant knee, to receive forgiveness. In a vision shown to him by the angel Michael, Adam witnesses everything that will happen to mankind until the Great Flood. Adam is very upset by this vision of the future, so Michael also tells him about humankind's potential redemption from original sin through Jesus Christ (whom Michael calls "King Messiah").

Adam and Eve are cast out of Eden, and Michael says that Adam may find "a paradise within thee, happier far". Adam and Eve also now have a more distant relationship with God, who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the tangible Father in the Garden of Eden).

Characters

Satan

Satan is the first major character introduced in the poem. Formerly called Lucifer, he was the most beautiful of all angels in Heaven, and is a tragic figure who describes himself with the now-famous quote "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven." He is introduced to Hell after he leads a failed rebellion to wrest control of Heaven from God. Satan's desire to rebel against his creator stems from his unwillingness to be subjugated by God and his Son, claiming that angels are "self-begot, self-raised,"[12] and thereby denying God's authority over them as their creator.

Satan is deeply arrogant, albeit powerful and charismatic. Satan's persuasive powers are evident throughout the book; not only is he cunning and deceptive, but he is also able to rally the fallen angels to continue in the rebellion after their agonizing defeat in the Angelic War. He argues that God rules as a tyrant and that all the angels ought to rule as gods.[13] Though commonly understood to be the antagonizing force in Paradise Lost, Satan may be best defined as a tragic or Hellenic hero. According to William McCollom, one quality of the classical tragic hero is that he is not perfectly good and that his defeat is caused by a tragic flaw, as Satan causes both the downfall of man and the eternal damnation of his fellow fallen angels despite his dedication to his comrades. In addition, Satan’s Hellenic qualities, such as his immense courage and perhaps, lack of completely defined morals, compound his tragic nature.[14]

Satan's status as a protagonist in the epic poem is debatable; Milton arguably characterizes him as such, but Satan lacks several key traits that would otherwise make him the definitive protagonist in the work. One deciding factor that insinuates his role as the protagonist in the story is that most often a protagonist is heavily characterized and far better described than the other characters, and the way the character is written is meant to make him seem more interesting or special to the reader [15] For that matter, Satan is both well described and is depicted as being quite versatile in that he is shown as having the capacity to do evil whilst retaining his characteristic sympathetic qualities and thus it is this complex and relatable nature makes him a likely candidate for the story’s overarching protagonist.[15]

According to Ibrahim Taha's definition of a protagonist the protagonist must be able to exist in and of himself or herself and that the secondary characters in the work exist only to further the plot for the protagonist.[16] Because Satan does not exist solely for himself, as without God he would not have a role to play in the story, he may not be viewed as protagonist because of the continual shifts in perspective and relative importance of characters in each book of the work. Satan’s existence in the story involves his rebellion against God and his determination to corrupt the beings he creates in order to create evil so that there can be a discernable balance and justice for both himself and his fallen angels. Therefore, it is more probable that he exists in order to combat God, making his status as the definitive protagonist of the work relative to each book.

Satan's status as a traditional hero in the work is similarly up to debate as the term “hero” evokes different meanings depending on the time and the person giving the definition and is thus a matter of contention within the text. According to Aristotle, a hero is someone who is “superhuman, godlike, and divine” but is also human.[17] A hero would have to either be a human with God-like powers or the offspring of God. While Milton gives reason to believe that Satan is superhuman, as he was originally an angel, he is anything but human. Therefore, according to Aristotle’s definition of a hero alone, Satan is not a hero. Torquato Tasso and Francesco Piccolomini expanded on Aristotle’s definition and declared that for someone to be considered heroic one has to be perfectly or overly virtuous.[18] Satan repeatedly demonstrates a lack of virtue throughout the story as he intends to tempt God’s creations with evil in order to destroy the good God is trying to create. Satan goes against God’s law and therefore becomes corrupt and lacking of virtue and, as Piccolimini warned, “vice may be mistaken for heroic virtue”.[17] Satan is very devoted to his cause, although that cause is evil but he strives to spin his sinister aspirations to appear as good ones. Satan achieves this end multiple times throughout the text as he riles up his band of fallen angels during his speech by deliberately telling them to do evil to explain God’s hypocrisy and again during his entreaty to Eve. He makes his intentions seem pure and positive even when they are rooted in evil and according to Steadman, this is the chief reason that readers often mistake Satan as a hero.[18]

Although Satan's army inevitably loses the war against God, Satan achieves a position of power and begins his reign in Hell with his band of loyal followers, composed of fallen angels, which is described to be a "third of heaven". Satan's characterization as the leader of a failing cause folds into this as well and is best exemplified through his own quote, "to be weak is to be miserable; Doing or Suffering", as through shared solidarity espoused by empowering rhetoric, Satan riles up his comrades in arms and keeps them focused towards their shared goal.[19] Similar to Milton’s republican sentiments of overthrowing the King of England for both better representation and parliamentary power, Satan argues that his shared rebellion with the fallen angels is an effort to “explain the hypocrisy of God”, and in doing so, they will be treated with the respect and acknowledgement that they deserve. As scholar Wayne Rebhorn argues, “Satan insists that he and his fellow revolutionaries held their places by right and even leading him to claim that they were self-created and self-sustained” and thus Satan’s position in the rebellion is much like that of his own real world creator.[20]

Adam

Adam is the first human created by God. Though initially alone, Adam demands a mate from God. Considered God's prized creation, Adam, along with his wife, rules over all the creatures of the world and resides in the Garden of Eden. He is more gregarious than Eve, and yearns for her company. His complete infatuation with Eve, while pure in and of itself, eventually contributes to his joining her in disobedience to God.

Unlike the Biblical Adam, before he leaves Paradise this version of Adam is given a glimpse of the future of mankind (including a synopsis of stories from the Old and New Testaments) by the Archangel Michael.

Eve

Eve is the second human created by God, taken from one of Adam's ribs and shaped into a female form of Adam. Far from the traditional model of a good wife, she is often unwilling to be submissive towards Adam. She is more intelligent and curious about external ideas than her husband. Though happy, she longs for knowledge and, more specifically, self-knowledge. Her first act in existence is to turn away from Adam and look at and ponder her own reflection. Eve is extremely beautiful and thoroughly in love with Adam, though may feel suffocated by his constant presence. One day, she convinces Adam that it would be good for them to split up and work different parts of the Garden. In her solitude, she is tempted by Satan to sin against God. Adam shortly follows along with her.

The Son of God

The Son of God is the spirit who will become incarnate as Jesus Christ, though he is never named explicitly, since he has not yet entered human form. Milton's God refers to the Son as "My word, my wisdom, and effectual might" (3.170), but Milton believed in a subordinationist doctrine of Christology that regarded the Son as secondary to the Father, His "great Vice-gerent" (5.609). The poem is not explicitly anti-trinitarian, but is consistent with Milton's convictions. The Son is the ultimate hero of the epic and is infinitely powerful, single-handedly defeating Satan and his followers and driving them into Hell. The Son of God tells Adam and Eve about God's judgment after their sin. He sacrificially volunteers to journey to the World, become a man himself, and redeem the Fall of Man through his own death and resurrection. In the final scene, a vision of Salvation through the Son of God is revealed to Adam by Michael. Still, the name, Jesus of Nazareth, and the details of Jesus' story are not depicted in the poem.[21]

God the Father

God the Father is the creator of Heaven, Hell, the world, and of everyone and everything there is, through the agency of His Son. He desires glory and praise from all his creations. He is an all-powerful, all-knowing, infinitely good being who cannot be overthrown by even the great army of angels Satan incites against him. The stated purpose of the poem is to justify the ways of God to men, so God often converses with the Son of God concerning his plans and reveals his motives regarding his actions. The poem portrays God's process of creation in the way that Milton believed it was done, with God creating Heaven, Earth, Hell, and all the creatures that inhabit these separate planes from part of Himself, not out of nothing.[22] Thus, according to Milton, the ultimate authority of God derives from his being the "author" of creation. Satan tries to justify his rebellion by denying this aspect of God and claiming self-creation, but he admits to himself this is not the case, and that God "deserved no such return/ From me, whom He created what I was."[23][24]

Raphael

Raphael is an archangel whom God sends to warn Adam about Satan's infiltration of Eden and to warn him that Satan is going to try to curse Adam and Eve. He also has a lengthy discussion with the curious Adam regarding creation and events which transpired in Heaven.

Michael

Michael is a mighty archangel who fought for God in the Angelic War. In the first battle, he wounds Satan terribly with a powerful sword that God designed to even cut through the substance of angels. After Adam and Eve disobey God by eating from the Tree of Knowledge, God sends the angel Michael to visit Adam and Eve. His duty is to escort Adam and Eve out of Paradise. Before he does this, Michael shows Adam visions of the future which cover an outline of the Bible, from the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis, up through the story of Jesus Christ in the New Testament.

Motifs

Marriage

Milton first presents Adam and Eve in Book IV with impartiality. The relationship between Adam and Eve is one of "mutual dependence, not a relation of domination or hierarchy." While the author does place Adam above Eve in regard to his intellectual knowledge, and in turn his relation to God, he also grants Eve the benefit of knowledge through experience. Hermine Van Nuis clarifies that although there is a sense of stringency associated with the specified roles of the male and the female, each unreservedly accepts the designated role because it is viewed as an asset.[25] Instead of believing that these roles are forced upon them, each uses the obligatory requirement as a strength in their relationship with each other. These minor discrepancies could be interpreted as an indication of the author’s view on the importance of mutuality between a husband and a wife.

When examining the relationship between Adam and Eve, critics tend to accept an either Adam- or Eve-centered view in terms of hierarchy and importance to God. David Mikics argues, by contrast, these positions "overstate the independence of the characters' stances, and therefore miss the way in which Adam and Eve are entwined with each other".[26] Milton's true vision reflects one where the husband and wife (in this instance, Adam and Eve) depend on each other and only through each other’s differences are able to thrive.[26]

Although Milton does not directly mention divorce, critics posit theories on Milton's view of divorce based on inferences found within the poem, and, of course, the tracts on divorce Milton wrote earlier in his life. Other works by Milton suggest he viewed marriage as an entity separate from the church. Discussing Paradise Lost, Biberman entertains the idea that "marriage is a contract made by both the man and the woman".[27] Based on this inference, Milton would believe that both man and woman would have equal access to divorce, as they do to marriage.

Feminist critics of Paradise Lost suggest that Eve is forbidden the knowledge of her own identity. Moments after her creation, before Eve is led to Adam, she becomes enraptured by an image reflected in the water (her own, unbeknownst to Eve).[28] God urges Eve to look away from her own image, her beauty, which is also the object of Adam’s desire. Adam delights in both her beauty and submissive charms, yet Eve may never be permitted to gaze upon her individual form. Critic Julia M. Walker argues that because Eve “neither recognizes nor names herself ... she can know herself only in relation to Adam.”[29] “Eve’s sense of self becomes important in its absence ... [she] is never allowed to know what she is supposed to see.”[30] Eve therefore knows not what she is, only what she is not: male. Starting in Book IV, Eve learns that Adam, the male form, is superior and “How beauty is excelled by manly grace/ And wisdom which alone is truly fair.”[31] Led by his gentle hand, she yields, a woman without individual purpose, destined to fall by “free will.”

Idolatry

Milton's 17th-century contemporaries by and large criticised Milton’s ideas and considered him as a radical, mostly because of his well-known Protestant views on politics and religion. One of Milton's greatest and most controversial arguments centres on his concept of what is idolatrous; this topic is deeply embedded in Paradise Lost.

Milton's first criticism of idolatry focuses on the practice of constructing temples and other buildings to serve as places of worship. In Book XI of Paradise Lost, Adam tries to atone for his sins by offering to build altars to worship God. In response, the angel Michael explains that Adam does not need to build physical objects to experience the presence of God.[32] Joseph Lyle points to this example, explaining "When Milton objects to architecture, it is not a quality inherent in buildings themselves he finds offensive, but rather their tendency to act as convenient loci to which idolatry, over time, will inevitably adhere."[33] Even if the idea is pure in nature, Milton still believes that it will unavoidably lead to idolatry simply because of the nature of humans. Instead of directing their thoughts towards God, as they should, humans tend to turn to erected objects and falsely invest their faith. While Adam attempts to build an altar to God, critics note Eve is similarly guilty of idolatry, but in a different manner. Harding believes Eve's narcissism and obsession with herself constitutes idolatry.[34] Specifically, Harding claims that "... under the serpent’s influence, Eve’s idolatry and self-deification foreshadow the errors into which her 'Sons' will stray."[34] Much like Adam, Eve falsely places her faith into herself, the Tree of Knowledge, and to some extent, the Serpent, all of which do not compare to the ideal nature of God.

Furthermore, Milton makes his views on idolatry more explicit with the creation of Pandæmonium and the exemplary allusion to Solomon's temple. In the beginning of Paradise Lost, as well as throughout the poem, there are several references to the rise and eventual fall of Solomon's temple. Critics elucidate that "Solomon’s temple provides an explicit demonstration of how an artefact moves from its genesis in devotional practice to an idolatrous end."[35] This example, out of the many presented, conveys Milton’s views on the dangers of idolatry distinctly. Even if one builds a structure in the name of God, even the best of intentions can become immoral. In addition, critics have drawn parallels between both Pandemonium and Saint Peter's Basilica, and the Pantheon. The majority of these similarities revolve around a structural likeness, but as Lyle explains, they play a greater role. By linking Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Pantheon to Pandemonium—an ideally false structure, the two famous buildings take on a false meaning.[36] This comparison best represents Milton's Protestant views, as it rejects both the purely Catholic perspective and the Pagan perspective.

In addition to rejecting Catholicism, Milton revolted against the idea of a monarch ruling by divine right. He saw the practice as idolatrous. Barbara Lewalski concludes that the theme of idolatry in Paradise Lost "is an exaggerated version of the idolatry Milton had long associated with the Stuart ideology of divine kingship".[37] In the opinion of Milton, any object, human or non-human, that receives special attention befitting of God, is considered idolatrous.

Interpretation and criticism

The writer and critic Samuel Johnson wrote that Paradise Lost shows off "[Milton's] peculiar power to astonish" and that "[Milton] seems to have been well acquainted with his own genius, and to know what it was that Nature had bestowed upon him more bountifully than upon others: the power of displaying the vast, illuminating the splendid, enforcing the awful, darkening the gloomy, and aggravating the dreadful."[38]

Milton scholar John Leonard interpreted the "impious war" between Heaven and Hell as civil war :[39]

Paradise Lost is, among other things, a poem about civil war. Satan raises 'impious war in Heav'n' (i 43) by leading a third of the angels in revolt against God. The term 'impious war' implies that civil war is impious. But Milton applauded the English people for having the courage to depose and execute King Charles I. In his poem, however, he takes the side of 'Heav'n's awful Monarch' (iv 960). Critics have long wrestled with the question of why an antimonarchist and defender of regicide should have chosen a subject that obliged him to defend monarchical authority

The editors at the Poetry Foundation argue that Milton's criticism of the English monarchy was being directed specifically at the Stuart monarchy and not at the monarchy system in general.[40]

In a similar vein, critic and writer C.S. Lewis argued that there was no contradiction in Milton's position in the poem since "Milton believed that God was his 'natural superior' and that Charles Stuart was not." Lewis interpreted the poem as a genuine Christian morality tale.[41]

Other critics, like William Empson, view it as a more ambiguous work, with Milton's complex characterization of Satan playing a large part in that perceived ambiguity.[42] Empson argued that "Milton deserves credit for making God wicked, since the God of Christianity is 'a wicked God.'" Leonard places Empson's interpretation "in the [Romantic interpretive] tradition of William Blake and Percy Bysshe Shelley."[39] As Blake famously wrote, "The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it."[43] This quotation succinctly represents the way in which the 18th- and 19th-century English Romantic poets viewed Milton.

Empson's view is more complex. Leonard points out that "Empson never denies that Satan's plan is wicked. What he does deny is that God is innocent of its wickedness: 'Milton steadily drives home that the inmost counsel of God was the Fortunate Fall of man; however wicked Satan's plan may be, it is God's plan too [since God in Paradise Lost is depicted as being both omniscient and omnipotent].'"[39] Leonard calls Empson's view "a powerful argument", he notes that this interpretation was challenged by Dennis Danielson in his book Milton's Good God (1982).[39]

Iconography

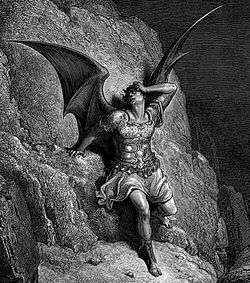

The first illustrations to accompany the text of Paradise Lost were added to the fourth edition of 1688, with one engraving prefacing each book, of which up to eight of the twelve were by Sir John Baptist Medina, one by Bernard Lens II, and perhaps up to four (including Books I and XII, perhaps the most memorable) by another hand.[44] The engraver was Michael Burghers (not 'Burgesse' as given in the Christ's College website). By 1730 the same images had been re-engraved on a smaller scale by Paul Fourdrinier.

Some of the most notable illustrators of Paradise Lost included William Blake, Gustave Doré and Henry Fuseli. However, the epic's illustrators also include John Martin, Edward Francis Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman, and many others.

Outside of book illustrations, the epic has also inspired other visual works by well-known painters like Salvador Dalí who executed a set of ten colour engravings in 1974.[45] Milton's achievement in writing Paradise Lost while blind (he dictated to helpers) inspired loosely biographical paintings by both Fuseli[46] and Eugène Delacroix.[47]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ "Paradise Lost: Introduction". Dartmouth College. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ Poetry Foundation Bio on Milton

- ↑ Milton's original line read "...justifie the wayes of God to men."[4][5]

- ↑ John Milton. Paradise Lost, Book I, l. 26. 1667. Hosted by Dartmouth. Accessed 13 December 2013.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 1:26.

- 1 2 3 Leonard 2000, p. xii.

- ↑ Leonard 2000, p. xiii.

- ↑ Broadbent 1972, p. 54.

- ↑ Forsythe, Neil (2002). The Satanic Epic. Princeton University.

- ↑ Abrahm, M.H., Stephen Greenblatt, Eds. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. New York: Norton, 2000.

- ↑ Teskey, Gordon (2005). "Introduction". Paradise Lost: A Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton. pp. xxvii–xxviii. ISBN 978-0393924282.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 5:860.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 5:794–802.

- ↑ McCollom, William G. ―The Downfall of the Tragic Hero.‖ College English 19.2 (1957): 51- 56.

- 1 2 (Taha, Ibrahim. "Heroism In Literature." The American Journal of Semiotics18.1/4 (2002): 107-26. Philosophy Document Center. Web. 12 Nov. 2014)

- ↑ Taha, Ibrahim. "Heroism In Literature." The American Journal of Semiotics18.1/4 (2002): 107-26. Philosophy Document Center. Web. 12 Nov. 2014

- 1 2 Steadman, John M. "Heroic Virtue and the Divine Image in Paradise Lost. "Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 22.1/2 (1959): pp. 89

- 1 2 Steadman, John M. "Heroic Virtue and the Divine Image in Paradise Lost. "Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 22.1/2 (1959): pp. 90

- ↑ Milton, John. Paradise Lost. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 9th ed. Vol. B. New York ; London: W.W. Norton, 2012. 1950. Print.

- ↑ Rebhorn, Wayne A. “The Humanist Tradition and Milton’s Satan: The Conservative as Revolutionary”. Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 13, No. 1, The English Renaissance (Winter 1973), pp. 81-93. Print.

- ↑ Marshall 1961, p. 17.

- ↑ Lehnhof 2008, p. 15.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 4:42–43.

- ↑ Lehnhof 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Van Nuis 2000, p. 50.

- 1 2 Mikics 2004, p. 22.

- ↑ Biberman 1999, p. 137.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 4:447–464.

- ↑ Walker 1998, p. 166.

- ↑ Walker 1998, p. 169.

- ↑ Milton 1674, 4:488–489.

- ↑ Milton 1674, Book 11.

- ↑ Lyle 2000, p. 139.

- 1 2 Harding 2007, p. 163.

- ↑ Lyle 2000, p. 140.

- ↑ Lyle 2000, p. 147.

- ↑ Lewalski 2003, p. 223.

- ↑ Johnson, Samuel. Lives of the English Poets. New York: Octagon, 1967.

- 1 2 3 4 Leonard, John. "Introduction." Paradise Lost. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- ↑ Poetry Foundation bio on Milton

- ↑ Leonard, John. "Introduction". Paradise Lost. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- ↑ Leonard, John. "Introduction". Paradise Lost. New York: Penguin, 2000.

- ↑ Blake, William. The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. 1793.

- ↑ Illustrating Paradise Lost from Christ's College, Cambridge, has all twelve on line. See Medina's article for more on the authorship, and all the illustrations, which are also in Commons.

- ↑ Lockport Street Gallery. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

- ↑ Art Institute of Chicago. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

- ↑ WikiPaintings. Retrieved on 2013-12-13.

References

- Anderson, G (January 2000), "The Fall of Satan in the Thought of St. Ephrem and John Milton", Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies, 3 (1)

- Biberman, M (January 1999), "Milton, Marriage, and a Woman's Right to Divorce", SEL: Studies in English Literature, 39 (1): 131–153, doi:10.2307/1556309, JSTOR 1556309

- Black, J, ed. (March 2007), "Paradise Lost", The Broadview Anthology of British Literature, A (Concise ed.), Peterborough, Ontario: Broadview Press, pp. 998–1061, ISBN 978-1-55111-868-0, OCLC 75811389

- Blake, W. (1793), The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, London.

- Blayney, B, ed. (1769), The King James Bible, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Bradford, R (July 1992), Paradise Lost (1st ed.), Philadelphia: Open University Press, ISBN 978-0-335-09982-5, OCLC 25050319

- Broadbent, John (1972), Paradise Lost: Introduction, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521096393

- Butler, G (February 1998), "Giants and Fallen Angels in Dante and Milton: The Commedia and the Gigantomachy in Paradise Lost", Modern Philosophy, 95 (3): 352–363

- Carter, R. and McRae, J. (2001). The Routledge History of Literature in English: Britain and Ireland. 2 ed. Oxon: Routledge.

- Carey, J; Fowler, A (1971), The Poems of John Milton, London

- Doerksen, D (December 1997), "Let There Be Peace': Eve as Redemptive Peacemaker in Paradise Lost, Book X", Milton Quarterly, 32 (4): 124–130, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1997.tb00499.x

- Eliot, T.S. (1957), On Poetry and Poets, London: Faber and Faber

- Eliot, T. S. (1932), "Dante", Selected Essays, New York: Faber and Faber, OCLC 70714546.

- Empson, W (1965), Milton's God (Revised ed.), London

- John Milton: A Short Introduction (2002 ed., paperback by Roy C. Flannagan, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-22620-8; 2008 ed., ebook by Roy Flannagan, Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-470-69287-5)

- Forsyth, N (2003), The Satanic Epic, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-11339-5

- Frye, N (1965), The Return of Eden: Five Essays on Milton's Epics, Toronto: University of Toronto Press

- Harding, P (January 2007), "Milton's Serpent and the Pagan Birth of Error", SEL: Studies in English Literature, 47 (1): 161–177, doi:10.1353/sel.2007.0003

- Hill, G (1905), Lynch, Jack, ed., Samuel Johnson: The Lives of the English Poets, 3 vols, Oxford: Clarendon, OCLC 69137084

- Kermode, F, ed. (1960), The Living Milton: Essays by Various Hands, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, ISBN 0-7100-1666-2, OCLC 17518893

- Kerrigan, W, ed. (2007), The Complete Poetry and Essential Prose of John Milton, New York: Random House, ISBN 978-0-679-64253-4, OCLC 81940956

- Lehnhof, K. (Summer 2004), "Paradise Lost and the Concept of Creation", South Central Review, 21 (2): 15–41, doi:10.1353/scr.2004.0021

- Leonard, John (2000), "Introduction", in Milton, John, Paradise Lost, New York: Penguin, ISBN 9780140424393

- Lewalski, B. (January 2003), "Milton and Idolatry", SEL: Studies in English Literature, 43 (1): 213–232, doi:10.1353/sel.2003.0008

- Lewis, C.S. (1942), A Preface to Paradise Lost, London: Oxford University Press, OCLC 822692

- Lyle, J (January 2000), "Architecture and Idolatry in Paradise Lost", SEL: Studies in English Literature, 40 (1): 139–155, doi:10.2307/1556158, JSTOR 1556158

- Marshall, W. H. (January 1961), "Paradise Lost: Felix Culpa and the Problem of Structure", Modern Language Notes, 76 (1): 15–20, doi:10.2307/3040476, JSTOR 3040476

- Mikics, D (2004), "Miltonic Marriage and the Challenge to History in Paradise Lost", Texas Studies in Literature and Language, 46 (1): 20–48, doi:10.1353/tsl.2004.0005

- Miller, T.C., ed. (1997), The Critical Response to John Milton's "Paradise Lost", Westport: Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-313-28926-2, OCLC 35762631

- Milton, J (1674), Paradise Lost (2nd ed.), London: S. Simmons

- Rajan, B (1947), Paradise Lost and the Seventeenth Century Reader, London: Chatto & Windus, OCLC 62931344

- Ricks, C.B. (1963), Milton's Grand Style, Oxford: Clarendon Press, OCLC 254429

- Stone, J.W. (May 1997), ""Man's effeminate s(lack)ness:" Androgyny and the Divided Unity of Adam and Eve", Milton Quarterly, 31 (2): 33–42, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.1997.tb00491.x

- Van Nuis, H (May 2000), "Animated Eve Confronting Her Animus: A Jungian Approach to the Division of Labor Debate in Paradise Lost", Milton Quarterly, 34 (2): 48–56, doi:10.1111/j.1094-348X.2000.tb00619.x

- Walker, Julia M. (1998), Medusa's Mirrors: Spenser, Shakespeare, Milton, and the Metamorphosis of the Female Self, University of Delaware Press, ISBN 978-0-87413-625-8

- Wheat, L (2008), Philip Pullman's His dark materials—a multiple allegory : attacking religious superstition in The lion, the witch, and the wardrobe and Paradise lost, Amherst, N.Y.: Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-1-59102-589-4, OCLC 152580912

Further reading

- Patrides, C. A. Approaches to Paradise Lost: The York Tercentenary Lectures (University of Toronto, 1968) ISBN 0-8020-1577-8

- Ryan J. Stark, "Paradise Lost as Incomplete Argument," 1650—1850: Aesthetics, Ideas, and Inquiries in the Early Modern Era (2011): 3–18.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paradise Lost. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Paradise Lost |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Gustave Doré Paradise Lost Illustrations from the University at Buffalo Libraries

- Major Online Resources on Paradise Lost

-

Paradise Lost public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Paradise Lost public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Online text

- Paradise Lost XHTML version at Dartmouth's Milton Reading Room

- Project Gutenberg text version 1

- Project Gutenberg text version 2

- Paradise Lost PDF/Ebook version with layout and fonts inspired by 17th century publications.

- paradiselost.org has the original poetry side-by-side with a translation to plain (prosaic) English

- Paradise Lost EPUB/MOBI version

Other information

- darkness visible – comprehensive site for students and others new to Milton: contexts, plot and character summaries, reading suggestions, critical history, gallery of illustrations of Paradise Lost, and much more. By students at Milton's Cambridge college, Christ's College.

- Selected bibliography at the Milton Reading Room – includes background, biography, criticism.

- Paradise Lost learning guide, quotes, close readings, thematic analyses, character analyses, teacher resources