Iliad

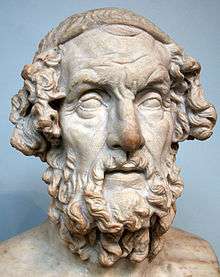

The Iliad (/ˈɪliəd/;[1] Ancient Greek: Ἰλιάς Ilias, pronounced [iː.li.ás] in Classical Attic; sometimes referred to as the Song of Ilion or Song of Ilium) is an ancient Greek epic poem in dactylic hexameter, traditionally attributed to Homer. Set during the Trojan War, the ten-year siege of the city of Troy (Ilium) by a coalition of Greek states, it tells of the battles and events during the weeks of a quarrel between King Agamemnon and the warrior Achilles.

Although the story covers only a few weeks in the final year of the war, the Iliad mentions or alludes to many of the Greek legends about the siege; the earlier events, such as the gathering of warriors for the siege, the cause of the war, and related concerns tend to appear near the beginning. Then the epic narrative takes up events prophesied for the future, such as Achilles' looming death and the sack of Troy, although the narrative ends before these events take place. However, as these events are prefigured and alluded to more and more vividly, when it reaches an end the poem has told a more or less complete tale of the Trojan War.

The Iliad is paired with something of a sequel, the Odyssey, also attributed to Homer. Along with the Odyssey, the Iliad is among the oldest extant works of Western literature, and its written version is usually dated to around the 8th century BC.[2] Recent statistical modelling based on language evolution gives a date of 760–710 BC.[3] In the modern vulgate (the standard accepted version), the Iliad contains 15,693 lines; it is written in Homeric Greek, a literary amalgam of Ionic Greek and other dialects.

Synopsis

- Note: Book numbers are in parentheses and come before the synopsis of the book.

(1) After an invocation to the Muses, the story launches in medias res towards the end of the Trojan War between the Trojans and the besieging Greeks. Chryses, a Trojan priest of Apollo, offers the Greeks wealth for the return of his daughter Chryseis, held captive of Agamemnon, the Greek leader. Although most of the Greek army is in favour of the offer, Agamemnon refuses. Chryses prays for Apollo's help, and Apollo causes a plague to afflict the Greek army.

After nine days of plague, Achilles, the leader of the Myrmidon contingent, calls an assembly to deal with the problem. Under pressure, Agamemnon agrees to return Chryseis to her father, but decides to take Achilles' captive, Briseis, as compensation. Angered, Achilles declares that he and his men will no longer fight for Agamemnon but will go home. Odysseus takes a ship and returns Chryseis to her father, whereupon Apollo ends the plague.

In the meantime, Agamemnon's messengers take Briseis away. Achilles becomes very upset, sits by the seashore, and prays to his mother, Thetis.[4] Achilles asks his mother to ask Zeus to bring the Greeks to the breaking point by the Trojans, so Agamemnon will realize how much the Greeks need Achilles. Thetis does so, and Zeus agrees.

(2) Zeus sends a dream to Agamemnon, urging him to attack Troy. Agamemnon heeds the dream but decides to first test the Greek army's morale, by telling them to go home. The plan backfires, and only the intervention of Odysseus, inspired by Athena, stops a rout.

Odysseus confronts and beats Thersites, a common soldier who voices discontent about fighting Agamemnon's war. After a meal, the Greeks deploy in companies upon the Trojan plain. The poet takes the opportunity to describe the provenance of each Greek contingent.

When news of the Greek deployment reaches King Priam, the Trojans too sortie upon the plain. In a list similar to that for the Greeks, the poet describes the Trojans and their allies.

(3) The armies approach each other, but before they meet, Paris offers to end the war by fighting a duel with Menelaus, urged by his brother and head of the Trojan army, Hector. While Helen tells Priam about the Greek commanders from the walls of Troy, both sides swear a truce and promise to abide by the outcome of the duel. Paris is beaten, but Aphrodite rescues him and leads him to bed with Helen before Menelaus can kill him.

(4) Pressured by Hera's hatred of Troy, Zeus arranges for the Trojan Pandaros to break the truce by wounding Menelaus with an arrow. Agamemnon rouses the Greeks, and battle is joined.

(5) In the fighting, Diomedes kills many Trojans, including Pandaros, and defeats Aeneas, whom Aphrodite rescues, but Diomedes attacks and wounds the goddess. Apollo faces Diomedes and warns him against warring with gods. Many heroes and commanders join in, including Hector, and the gods supporting each side try to influence the battle. Emboldened by Athena, Diomedes wounds Ares and puts him out of action.

(6) Hector rallies the Trojans and prevents a rout; the Greek Diomedes and the Trojan Glaukos find common ground and exchange unequal gifts. Hector enters the city, urges prayers and sacrifices, incites Paris to battle, bids his wife Andromache and son Astyanax farewell on the city walls, and rejoins the battle.

(7) Hector duels with Ajax, but nightfall interrupts the fight, and both sides retire. The Greeks agree to burn their dead, and build a wall to protect their ships and camp, while the Trojans quarrel about returning Helen. Paris offers to return the treasure he took and give further wealth as compensation, but not Helen, and the offer is refused. A day's truce is agreed for burning the dead, during which the Greeks also build their wall and a trench.

(8) The next morning, Zeus prohibits the gods from interfering, and fighting begins anew. The Trojans prevail and force the Greeks back to their wall, while Hera and Athena are forbidden to help. Night falls before the Trojans can assail the Greek wall. They camp in the field to attack at first light, and their watchfires light the plain like stars.

(9) Meanwhile, the Greeks are desperate. Agamemnon admits his error, and sends an embassy composed of Odysseus, Ajax, Phoenix, and two heralds to offer Briseis and extensive gifts to Achilles, who has been camped next to his ships throughout, if only he will return to the fighting. Achilles and his companion Patroclus receive the embassy well, but Achilles angrily refuses Agamemnon's offer and declares that he would only return to battle if the Trojans reached his ships and threatened them with fire. The embassy returns empty-handed.

(10) Later that night, Odysseus and Diomedes venture out to the Trojan lines, kill the Trojan Dolon, and wreak havoc in the camps of some Thracian allies of Troy's.

(11) In the morning, the fighting is fierce, and Agamemnon, Diomedes, and Odysseus are all wounded. Achilles sends Patroclus from his camp to inquire about the Greek casualties, and while there Patroclus is moved to pity by a speech of Nestor's.

(12) The Trojans attack the Greek wall on foot. Hector, ignoring an omen, leads the terrible fighting. The Greeks are overwhelmed and routed, the wall's gate is broken, and Hector charges in.

(13) Many fall on both sides. The Trojan seer Polydamas urges Hector to fall back and warns him about Achilles, but is ignored.

(14) Hera seduces Zeus and lures him to sleep, allowing Poseidon to help the Greeks, and the Trojans are driven back onto the plain.

(15) Zeus awakes and is enraged by Poseidon's intervention. Against the mounting discontent of the Greek-supporting gods, Zeus sends Apollo to aid the Trojans, who once again breach the wall, and the battle reaches the ships.

(16) Patroclus cannot stand to watch any longer and begs Achilles to be allowed to defend the ships. Achilles relents and lends Patroclus his armor, but sends him off with a stern admonition not to pursue the Trojans, lest he take Achilles' glory. Patroclus leads the Myrmidons into battle and arrives as the Trojans set fire to the first ships. The Trojans are routed by the sudden onslaught, and Patroclus begins his assault by killing the Trojan hero Sarpedon. Patroclus, ignoring Achilles' command, pursues and reaches the gates of Troy, where Apollo himself stops him. Patroclus is set upon by Apollo and Euphorbos, and is finally killed by Hector.

(17) Hector takes Achilles' armor from the fallen Patroclus, but fighting develops around Patroclus' body.

(18) Achilles is mad with grief when he hears of Patroclus' death and vows to take vengeance on Hector; his mother Thetis grieves, too, knowing that Achilles is fated to die young if he kills Hector. Achilles is urged to help retrieve Patroclus' body but has no armour. Made brilliant by Athena, Achilles stands next to the Greek wall and roars in rage. The Trojans are dismayed by his appearance, and the Greeks manage to bear Patroclus' body away. Polydamas urges Hector again to withdraw into the city; again Hector refuses, and the Trojans camp on the plain at nightfall. Patroclus is mourned. Meanwhile, at Thetis' request, Hephaestus fashions a new set of armor for Achilles, including a magnificently wrought shield.

(19) In the morning, Agamemnon gives Achilles all the promised gifts, including Briseis, but Achilles is indifferent to them. Achilles fasts while the Greeks take their meal, straps on his new armor, and heaves his great spear. His horse Xanthos prophesies to Achilles his death. Achilles drives his chariot into battle.

(20) Zeus lifts the ban on the gods' interference, and the gods freely help both sides. Achilles, burning with rage and grief, slays many.

(21) Driving the Trojans before him, Achilles cuts off half their number in the river Skamandros and proceeds to slaughter them, filling the river with the dead. The river, angry at the killing, confronts Achilles but is beaten back by Hephaestus' firestorm. The gods fight among themselves. The great gates of the city are opened to receive the fleeing Trojans, and Apollo leads Achilles away from the city by pretending to be a Trojan.

(22) When Apollo reveals himself to Achilles, the Trojans have retreated into the city, all except for Hector, who, having twice ignored the counsels of Polydamas, feels the shame of the rout and resolves to face Achilles, despite the pleas of his parents, Priam and Hecuba. When Achilles approaches, Hector's will fails him, and he is chased around the city by Achilles. Finally, Athena tricks him into stopping, and he turns to face his opponent. After a brief duel, Achilles stabs Hector through the neck. Before dying, Hector reminds Achilles that he, too, is fated to die in the war. Achilles takes Hector's body and dishonours it.

(23) The ghost of Patroclus comes to Achilles in a dream and urges the burial of his body. The Greeks hold a day of funeral games, and Achilles gives out the prizes.

(24) Dismayed by Achilles' continued abuse of Hector's body, Zeus decides that it must be returned to Priam. Led by Hermes, Priam takes a wagon out of Troy, across the plains, and into the Greek camp unnoticed. He clasps Achilles by the knees and begs for his son's body. Achilles is moved to tears, and the two lament their losses in the war. After a meal, Priam carries Hector's body back into Troy. Hector is buried, and the city mourns.

Major characters

The many characters of the Iliad are catalogued; the latter-half of Book II, the "Catalogue of Ships", lists commanders and cohorts; battle scenes feature quickly slain minor characters.

Achaeans

- The Achaeans (Ἀχαιοί) – also called Hellenes (Greeks), Danaans (Δαναοί), or Argives (Ἀργεĩοι).

- Agamemnon – King of Mycenae, leader of the Greeks.

- Achilles – son of Peleus, foremost warrior, leader of the Myrmidons and King of Phthia,[5] son of a divine mother, Thetis.

- Odysseus – King of Ithaca, Greek commander.

- Ajax the Greater – son of Telamon and king of Salamis.

- Menelaus – King of Sparta, husband of Helen and brother of Agamemnon.

- Diomedes – son of Tydeus, King of Argos.

- Ajax the Lesser – son of Oileus, often partner of Ajax the Greater.

- Patroclus – Achilles' closest companion.

- Nestor – King of Pylos, and trusted advisor to Agamemnon.

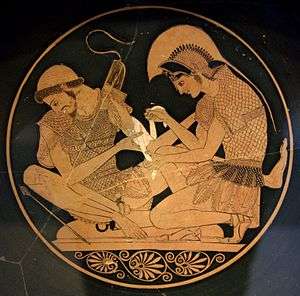

Achilles and Patroclus

Much debate has surrounded the nature of the relationship of Achilles and Patroclus, as to whether it can be described as a homoerotic one or not. Classical and Hellenistic Athenian scholars perceived it as pederastic,[6] while others perceived it as a platonic warrior-bond.[7]

Trojans

- The Trojan men

- Hector – son of King Priam and the foremost Trojan warrior.

- Aeneas – son of Anchises and Aphrodite.

- Deiphobus – brother of Hector and Paris.

- Paris – Helen's lover-abductor.

- Priam – the aged King of Troy.

- Polydamas – a prudent commander whose advice is ignored; he is Hector's foil.

- Agenor – a Trojan warrior, son of Antenor, who attempts to fight Achilles (Book XXI).

- Sarpedon, son of Zeus – killed by Patroclus. Was friend of Glaucus and co-leader of the Lycians (fought for the Trojans).

- Glaucus, son of Hippolochus – friend of Sarpedon and co-leader of the Lycians (fought for the Trojans).

- Euphorbus – first Trojan warrior to wound Patroclus.

- Dolon – a spy upon the Greek camp (Book X).

- Antenor – King Priam's advisor, who argues for returning Helen to end the war.

- Polydorus – son of Priam and Laothoe.

- Pandarus – famous archer and son of Lycaon.

- The Trojan women

- Hecuba (Ἑκάβη, Hekabe) – Priam's wife, mother of Hector, Cassandra, Paris, and others.

- Helen (Ἑλένη) – daughter of Zeus; Menelaus's wife; espoused first to Paris, then to Deiphobus; her abduction by Paris precipitated the war.

- Andromache – Hector's wife, mother of Astyanax.

- Cassandra – Priam's daughter.

- Briseis – a Trojan woman captured by Achilles from a previous siege, over whom Achilles's quarrel with Agamemnon began.

Gods

In the literary Trojan War of the Iliad, the Olympian gods, goddesses, and minor deities fight and play great roles in human warfare. Unlike practical Greek religious observance, Homer's portrayals of them suited his narrative purpose, being very different from the polytheistic ideals Greek society used. To wit, the Classical-era historian Herodotus says that Homer, and his contemporary, the poet Hesiod, were the first artists to name and describe their appearance and characters.[8]

In Greek Gods Human Lives: What We Can Learn From Myths, Mary Lefkowitz discusses the relevance of divine action in the Iliad, attempting to answer the question of whether or not divine intervention is a discrete occurrence (for its own sake), or if such godly behaviors are mere human character metaphors. The intellectual interest of Classic-era authors, such as Thucydides and Plato, was limited to their utility as "a way of talking about human life rather than a description or a truth", because, if the gods remain religious figures, rather than human metaphors, their "existence"—without the foundation of either dogma or a bible of faiths—then allowed Greek culture the intellectual breadth and freedom to conjure gods fitting any religious function they required as a people.[9][10]

In The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, psychologist Julian Jaynes uses the Iliad as a major supporting evidence for his theory of Bicameralism, which posits that until about the time described in the Iliad, humans had a much different mentality than present day humans, essentially lacking in what we call consciousness. He suggests that humans heard and obeyed commands from what they identified as gods, until the change in human mentality that incorporated the motivating force into the conscious self. He points out that almost every action in the Iliad is directed, caused, or influenced by a god, and that earlier translations show an astonishing lack of words suggesting thought, planning, or introspection. Those that do appear, he argues, are misinterpretations made by translators imposing a modern mentality on the characters.[11]

- The major deities:

- The minor deities:

Themes

Nostos

Nostos (νόστος, "homecoming") occurs seven times in the poem.[12] Thematically, the concept of homecoming is much explored in Ancient Greek literature, especially in the post-war homeward fortunes experienced by the Atreidae (Agamemnon and Menelaus), and Odysseus (see the Odyssey). Thus, nostos is impossible without sacking Troy—King Agamemnon's motive for winning, at any cost.

Kleos

Kleos (κλέος, "glory, fame") is the concept of glory earned in heroic battle.[13] For most of the Greek invaders of Troy, notably Odysseus, kleos is earned in a victorious nostos (homecoming). Yet, Achilles must choose only one of the two rewards, either nostos or kleos.[14] In Book IX (IX.410–16), he poignantly tells Agamemnon's envoys—Odysseus, Phoenix, Ajax—begging his reinstatement to battle about having to choose between two fates (διχθαδίας κήρας, 9.411).[15]

The passage reads (the translation is Lattimore's):

|

μήτηρ γάρ τέ μέ φησι θεὰ Θέτις ἀργυρόπεζα (410) |

For my mother Thetis the goddess of silver feet tells me |

In forgoing his nostos, he will earn the greater reward of kleos aphthiton (κλέος ἄφθιτον, "fame imperishable").[15] In the poem, aphthiton (ἄφθιτον, "imperishable") occurs five other times,[18] each occurrence denotes an object: Agamemnon's sceptre, the wheel of Hebe's chariot, the house of Poseidon, the throne of Zeus, the house of Hephaestus. Translator Lattimore renders kleos aphthiton as forever immortal and as forever imperishable—connoting Achilles's mortality by underscoring his greater reward in returning to battle Troy.

Kleos is often given visible representation by the prizes won in battle. When Agamemnon takes Briseis from Achilles, he takes away a portion of the kleos he had earned.

Achilles' shield, crafted by Hephaestus and given to him by his mother Thetis, bears an image of stars in the centre. The stars conjure profound images of the place of a single man, no matter how heroic, in the perspective of the entire cosmos.

Timê

Akin to kleos is timê (τιμή, "respect, honor"), the concept denoting the respectability an honorable man accrues with accomplishment (cultural, political, martial), per his station in life. In Book I, the Greek troubles begin with King Agamemnon's dishonorable, unkingly behavior—first, by threatening the priest Chryses (1.11), then, by aggravating them in disrespecting Achilles, by confiscating Briseis from him (1.171). The warrior's consequent rancor against the dishonorable king ruins the Greek military cause.

Wrath

The poem's initial word, μῆνιν (mēnin, accusative of μῆνις, mēnis, "wrath, rage, fury"), establishes the Iliad's principal theme: The "Wrath of Achilles".[19] His personal rage and wounded soldier's vanity propel the story: the Greeks' faltering in battle, the slayings of Patroclus and Hector, and the fall of Troy. In Book I, the Wrath of Achilles first emerges in the Achilles-convoked meeting, between the Greek kings and the seer Calchas. King Agamemnon dishonours Chryses, the Trojan priest of Apollo, by refusing with a threat the restitution of his daughter, Chryseis—despite the proffered ransom of "gifts beyond count".[20] The insulted priest prays his god's help, and a nine-day rain of divine plague arrows falls upon the Greeks. Moreover, in that meeting, Achilles accuses Agamemnon of being "greediest for gain of all men".[21] To that, Agamemnon replies:

But here is my threat to you.

Even as Phoibos Apollo is taking away my Chryseis.

I shall convey her back in my own ship, with my own

followers; but I shall take the fair-cheeked Briseis,

your prize, I myself going to your shelter, that you may learn well

how much greater I am than you, and another man may shrink back

from likening himself to me and contending against me.[22]

After that, only Athena stays Achilles's wrath. He vows to never again obey orders from Agamemnon. Furious, Achilles cries to his mother, Thetis, who persuades Zeus's divine intervention—favouring the Trojans—until Achilles's rights are restored. Meanwhile, Hector leads the Trojans to almost pushing the Greeks back to the sea (Book XII). Later, Agamemnon contemplates defeat and retreat to Greece (Book XIV). Again, the Wrath of Achilles turns the war's tide in seeking vengeance when Hector kills Patroclus. Aggrieved, Achilles tears his hair and dirties his face. Thetis comforts her mourning son, who tells her:

So it was here that the lord of men Agamemnon angered me.

Still, we will let all this be a thing of the past, and for all our

sorrow beat down by force the anger deeply within us.

Now I shall go, to overtake that killer of a dear life,

Hektor; then I will accept my own death, at whatever

time Zeus wishes to bring it about, and the other immortals.[23]

Accepting the prospect of death as fair price for avenging Patroclus, he returns to battle, dooming Hector and Troy, thrice chasing him 'round the Trojan walls, before slaying him, then dragging the corpse behind his chariot, back to camp.

Fate

Fate (κήρ, kēr, "fated death") propels most of the events of the Iliad. Once set, gods and men abide it, neither truly able nor willing to contest it. How fate is set is unknown, but it is told by the Fates and by Zeus through sending omens to seers such as Calchas. Men and their gods continually speak of heroic acceptance and cowardly avoidance of one's slated fate.[24] Fate does not determine every action, incident, and occurrence, but it does determine the outcome of life—before killing him, Hector calls Patroclus a fool for cowardly avoidance of his fate, by attempting his defeat; Patroclus retorts: [25]

No, deadly destiny, with the son of Leto, has killed me,

and of men it was Euphorbos; you are only my third slayer.

And put away in your heart this other thing that I tell you.

You yourself are not one who shall live long, but now already

death and powerful destiny are standing beside you,

to go down under the hands of Aiakos' great son, Achilleus.[26]

Here, Patroclus alludes to fated death by Hector's hand, and Hector's fated death by Achilles's hand. Each accepts the outcome of his life, yet, no-one knows if the gods can alter fate. The first instance of this doubt occurs in Book XVI. Seeing Patroclus about to kill Sarpedon, his mortal son, Zeus says:

Ah me, that it is destined that the dearest of men, Sarpedon,

must go down under the hands of Menoitios' son Patroclus.[27]

About his dilemma, Hera asks Zeus:

Majesty, son of Kronos, what sort of thing have you spoken?

Do you wish to bring back a man who is mortal, one long since

doomed by his destiny, from ill-sounding death and release him?

Do it, then; but not all the rest of us gods shall approve you.[28]

In deciding between losing a son or abiding fate, Zeus, King of the Gods, allows it. This motif recurs when he considers sparing Hector, whom he loves and respects. Again, Hera asks him:

Father of the shining bolt, dark misted, what is this you said?

Do you wish to bring back a man who is mortal, one long since

doomed by his destiny, from ill-sounding death and release him?

Do it, then; but not all the rest of us gods shall approve you.[29]

Again, Zeus appears capable of altering fate, but does not, deciding instead to abide set outcomes; yet, contrariwise, fate spares Aeneas, after Apollo convinces the over-matched Trojan to fight Achilles. Poseidon cautiously speaks:

But come, let us ourselves get him away from death, for fear

the son of Kronos may be angered if now Achilleus

kills this man. It is destined that he shall be the survivor,

that the generation of Dardanos shall not die ...[30]

Divinely aided, Aeneas escapes the wrath of Achilles and survives the Trojan War. Whether or not the gods can alter fate, they do abide it, despite its countering their human allegiances; thus, the mysterious origin of fate is a power beyond the gods. Fate implies the primeval, tripartite division of the world that Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades effected in deposing their father, Cronus, for its dominion. Zeus took the Air and the Sky, Poseidon the Waters, and Hades the Underworld, the land of the dead—yet they share dominion of the Earth. Despite the earthly powers of the Olympic gods, only the Three Fates set the destiny of Man.

Date and textual history

The poem dates to the archaic period of Classical Antiquity. Scholarly consensus mostly places it in the 8th century BC, although some favour a 7th-century date. Herodotus placed Homer at approximately 400 years before his own time, which would place Homer at circa 850 BC.

The historical backdrop of the poem is the time of the Late Bronze Age collapse, in the early 12th century BC. Homer is thus separated from his subject matter by about 400 years, the period known as the Greek Dark Ages. Intense scholarly debate has surrounded the question of which portions of the poem preserve genuine traditions from the Mycenaean period. The Catalogue of Ships in particular has the striking feature that its geography does not portray Greece in the Iron Age, the time of Homer, but as it was before the Dorian invasion.

The title Ἰλιάς "Ilias" (genitive Ἰλιάδος "Iliados") is elliptic for ἡ ποίησις Ἰλιάς "he poiesis Ilias", meaning "the Trojan poem". Ἰλιάς, "of Troy", is the specifically feminine adjective form from Ἴλιον, "Troy"; the masculine adjective form would be Ἰλιακός or Ἴλιος.[31] It is used by Herodotus.[32]

Venetus A, copied in the 10th century AD, is the oldest fully extant manuscript of the Iliad.[33] The first edition of the "Iliad",editio princeps, by Demetrius Chalcondyles was printed in Florence in 1488.[34]

The Iliad as oral tradition

In antiquity, the Greeks applied the Iliad and the Odyssey as the bases of pedagogy. Literature was central to the educational-cultural function of the itinerant rhapsode, who composed consistent epic poems from memory and improvisation, and disseminated them, via song and chant, in his travels and at the Panathenaic Festival of athletics, music, poetics, and sacrifice, celebrating Athena's birthday.[35]

Originally, Classical scholars treated the Iliad and the Odyssey as written poetry, and Homer as a writer. Yet, by the 1920s, Milman Parry (1902–1935) had launched a movement claiming otherwise. His investigation of the oral Homeric style—"stock epithets" and "reiteration" (words, phrases, stanzas) —established that these formulae were artifacts of oral tradition easily applied to an hexametric line. A two-word stock epithet (e.g. "resourceful Odysseus") reiteration may complement a character name by filling a half-line, thus, freeing the poet to compose a half-line of "original" formulaic text to complete his meaning.[36] In Yugoslavia, Parry and his assistant, Albert Lord (1912–1991), studied the oral-formulaic composition of Serbian oral poetry, yielding the Parry/Lord thesis that established oral tradition studies, later developed by Eric Havelock, Marshall McLuhan, Walter Ong, and Gregory Nagy.

In The Singer of Tales (1960), Lord presents likenesses between the tragedies of the Greek Patroclus, in the Iliad, and of the Sumerian Enkidu, in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and claims to refute, with "careful analysis of the repetition of thematic patterns", that the Patroclus storyline upsets Homer's established compositional formulae of "wrath, bride-stealing, and rescue"; thus, stock-phrase reiteration does not restrict his originality in fitting story to rhyme.[37][38] Likewise, in The Arming Motif, Prof. James Armstrong reports that the poem's formulae yield richer meaning because the "arming motif" diction—describing Achilles, Agamemnon, Paris, and Patroclus—serves to "heighten the importance of ... an impressive moment", thus, "[reiteration] creates an atmosphere of smoothness", wherein, Homer distinguishes Patroclus from Achilles, and foreshadows the former's death with positive and negative turns of phrase.[39][40]

In the Iliad, occasional syntactic inconsistency may be an oral tradition effect—for example, Aphrodite is "laughter-loving", despite being painfully wounded by Diomedes (Book V, 375); and the divine representations may mix Mycenaean and Greek Dark Age (ca. 1150–800 BC) mythologies, parallelling the hereditary basileis nobles (lower social rank rulers) with minor deities, such as Scamander, et al.[41]

Warfare in the Iliad

Depiction of infantry combat

Despite Mycenae and Troy being maritime powers, the Iliad features no sea battles.[42] So, the Trojan shipwright (of the ship that transported Helen to Troy), Phereclus, fights afoot, as an infantryman.[43] The battle dress and armour of hero and soldier are well-described. They enter battle in chariots, launching javelins into the enemy formations, then dismount—for hand-to-hand combat with yet more javelin throwing, rock throwing, and if necessary hand to hand sword and a shoulder-borne hoplon (shield) fighting.[44] Ajax the Greater, son of Telamon, sports a large, rectangular shield (σάκος, sakos) with which he protects himself and Teucer, his brother:

- Ninth came Teucer, stretching his curved bow.

- He stood beneath the shield of Ajax, son of Telamon.

- As Ajax cautiously pulled his shield aside,

- Teucer would peer out quickly, shoot off an arrow,

- hit someone in the crowd, dropping that soldier

- right where he stood, ending his life—then he'd duck back,

- crouching down by Ajax, like a child beside its mother.

- Ajax would then conceal him with his shining shield.

- (Iliad 8.267–72, Ian Johnston, translator)

Ajax's cumbersome shield is more suitable for defence than for offence, while his cousin, Achilles, sports a large, rounded, octagonal shield that he successfully deploys along with his spear against the Trojans:

- Just as a man constructs a wall for some high house,

- using well-fitted stones to keep out forceful winds,

- that's how close their helmets and bossed shields lined up,

- shield pressing against shield, helmet against helmet

- man against man. On the bright ridges of the helmets,

- horsehair plumes touched when warriors moved their heads.

- That's how close they were to one another.

- (Iliad 16.213–7, Ian Johnston, translator)

In describing infantry combat, Homer names the phalanx formation,[45] but most scholars do not believe the historical Trojan War was so fought.[46] In the Bronze Age, the chariot was the main battle transport-weapon (e.g. the Battle of Kadesh). The available evidence, from the Dendra armour and the Pylos Palace paintings, indicate the Mycenaeans used two-man chariots, with a long-spear-armed principal rider, unlike the three-man Hittite chariots with short-spear-armed riders, and unlike the arrow-armed Egyptian and Assyrian two-man chariots. Nestor spearheads his troops with chariots; he advises them:

- In your eagerness to engage the Trojans,

- don't any of you charge ahead of others,

- trusting in your strength and horsemanship.

- And don't lag behind. That will hurt our charge.

- Any man whose chariot confronts an enemy's

- should thrust with his spear at him from there.

- That's the most effective tactic, the way

- men wiped out city strongholds long ago —

- their chests full of that style and spirit.

- (Iliad 4.301–09, Ian Johnston, translator)

Although Homer's depictions are graphic, it can be seen in the very end that victory in war is a far more somber occasion, where all that is lost becomes apparent. On the other hand, the funeral games are lively, for the dead man's life is celebrated. This overall depiction of war runs contrary to many other ancient Greek depictions, where war is an aspiration for greater glory.

Influence on classical Greek warfare

While the Homeric poems (the Iliad in particular) were not necessarily revered scripture of the ancient Greeks, they were most certainly seen as guides that were important to the intellectual understanding of any educated Greek citizen. This is evidenced by the fact that in the late fifth century BC, "it was the sign of a man of standing to be able to recite the Iliad and Odyssey by heart."[47] Moreover, it can be argued that the warfare shown in the Iliad, and the way in which it was depicted, had a profound and very traceable effect on Greek warfare in general. In particular, the effect of epic literature can be broken down into three categories: tactics, ideology, and the mindset of commanders. In order to discern these effects, it is necessary to take a look at a few examples from each of these categories.

Much of the detailed fighting in the Iliad is done by the heroes in an orderly, one-on-one fashion. Much like the Odyssey, there is even a set ritual which must be observed in each of these conflicts. For example, a major hero may encounter a lesser hero from the opposing side, in which case the minor hero is introduced, threats may be exchanged, and then the minor hero is slain. The victor often strips the body of its armor and military accoutrements.[48] Here is an example of this ritual and this type of one-on-one combat in the Iliad:

There Telamonian Ajax struck down the son of Anthemion, Simoeisios in his stripling's beauty, whom once his mother descending from Ida bore beside the banks of Simoeis when she had followed her father and mother to tend the sheepflocks. Therefore they called him Simoeisios; but he could not render again the care of his dear parents; he was short-lived, beaten down beneath the spear of high-hearted Ajax, who struck him as he first came forward beside the nipple of the right breast, and the bronze spearhead drove clean through the shoulder.[49]

The biggest issue in reconciling the connection between the epic fighting of the Iliad and later Greek warfare is the phalanx, or hoplite, warfare seen in Greek history well after Homer's Iliad. While there are discussions of soldiers arrayed in semblances of the phalanx throughout the Iliad, the focus of the poem on the heroic fighting, as mentioned above, would seem to contradict the tactics of the phalanx. However, the phalanx did have its heroic aspects. The masculine one-on-one fighting of epic is manifested in phalanx fighting on the emphasis of holding one's position in formation. This replaces the singular heroic competition found in the Iliad.[50]

One example of this is the Spartan tale of 300 picked men fighting against 300 picked Argives. In this battle of champions, only two men are left standing for the Argives and one for the Spartans. Othryades, the remaining Spartan, goes back to stand in his formation with mortal wounds while the remaining two Argives go back to Argos to report their victory. Thus, the Spartans claimed this as a victory, as their last man displayed the ultimate feat of bravery by maintaining his position in the phalanx.[51]

In terms of the ideology of commanders in later Greek history, the Iliad has an interesting effect. The Iliad expresses a definite disdain for tactical trickery, when Hector says, before he challenges the great Ajax:

I know how to storm my way into the struggle of flying horses; I know how to tread the measures on the grim floor of the war god. Yet great as you are I would not strike you by stealth, watching

for my chance, but openly, so, if perhaps I might hit you.[52]

However, despite examples of disdain for this tactical trickery, there is reason to believe that the Iliad, as well as later Greek warfare, endorsed tactical genius on the part of their commanders. For example, there are multiple passages in the Iliad with commanders such as Agamemnon or Nestor discussing the arraying of troops so as to gain an advantage. Indeed, the Trojan War is won by a notorious example of Greek guile in the Trojan Horse. This is even later referred to by Homer in the Odyssey. The connection, in this case, between guileful tactics of the Greeks in the Iliad and those of the later Greeks is not a difficult one to find. Spartan commanders, often seen as the pinnacle of Greek military prowess, were known for their tactical trickery, and, for them, this was a feat to be desired in a commander. Indeed, this type of leadership was the standard advice of Greek tactical writers.[53]

Ultimately, while Homeric (or epic) fighting is certainly not completely replicated in later Greek warfare, many of its ideals, tactics, and instruction are.[54]

Hans van Wees argues that the period that the descriptions of warfare relate can be pinned down fairly specifically—to the first half of the 7th century BC.[55]

Influence on the arts and literature

The Iliad was a standard work of great importance already in Classical Greece and remained so throughout the Hellenistic and Byzantine periods. It made its return to Italy and Western Europe beginning in the 15th century, primarily through translations into Latin and the vernacular languages. Prior to this reintroduction, a shortened Latin version of the poem, known as the Ilias Latina, was very widely studied and read as a basic school text. The West, however, had tended to look at Homer as a liar as they believed they possessed much more down to earth and realistic eyewitness accounts of the Trojan War written by Dares and Dictys Cretensis who were supposedly present at the events.

These late antique forged accounts formed the basis of several eminently popular medieval chivalric romances, most notably those of Benoit de Sainte-Maure and Guido delle Colonne. These in turn spawned many others in various European languages, such as the first printed English book, the 1473 Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye. Other accounts read in the Middle Ages were antique Latin retellings such as the Excidium Troiae and works in the vernaculars such as the Icelandic Troy Saga. Even without Homer, the Trojan War story had remained central to Western European medieval literary culture and its sense of identity. Most nations and several royal houses traced their origins to heroes at the Trojan War. Britain was supposedly settled by the Trojan Brutus, for instance.

Subjects from the Trojan War were a favourite among ancient Greek dramatists. Aeschylus' trilogy, the Oresteia, comprising Agamemnon, The Libation Bearers, and The Eumenides, follows the story of Agamemnon after his return from the war.

Homer also came to be of great influence in European culture with the resurgence of interest in Greek antiquity during the Renaissance, and it remains the first and most influential work of the Western canon.

William Shakespeare used the plot of the Iliad as source material for his play Troilus and Cressida, but focused on a medieval legend, the love story of Troilus, son of King Priam of Troy, and Cressida, daughter of the Trojan soothsayer Calchas. The play, often considered to be a comedy, reverses traditional views on events of the Trojan War and depicts Achilles as a coward, Ajax as a dull, unthinking mercenary, etc.

William Theed the elder made an impressive bronze statue of Thetis as she brought Achilles his new armor forged by Hephaesthus. It has been on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City since 2013.

Robert Browning's poem Development discusses his childhood introduction to the matter of the Iliad and his delight in the epic, as well as contemporary debates about its authorship.

20th century

Simone Weil wrote the essay The Iliad or the Poem of Force in 1939 shortly after the commencement of World War II. The essay describes how the Iliad demonstrates the way force, exercised to the extreme in war, reduces both victim and aggressor to the level of the slave and the unthinking automaton.[56]

The 1954 Broadway musical The Golden Apple by librettist John Treville Latouche and composer Jerome Moross was freely adapted from the Iliad and the Odyssey, re-setting the action to America's Washington state in the years after the Spanish–American War, with events inspired by the Iliad in Act One and events inspired by the Odyssey in Act Two.

Christa Wolf's 1983 novel Cassandra is a critical engagement with the Iliad. Wolf's narrator is Cassandra, whose thoughts we hear at the moment just before her murder by Clytemnestra in Sparta. Wolf's narrator presents a feminist's view of the war, and of war in general. Cassandra's story is accompanied by four essays which Wolf delivered as the Frankfurter Poetik-Vorlesungen. The essays present Wolf's concerns as a writer and rewriter of this canonical story and show the genesis of the novel through Wolf's own readings and in a trip she took to Greece.

David Melnick's Men in Aida (cf. μῆνιν ἄειδε) (1983) is a postmodern homophonic translation of Book One into a farcical bathhouse scenario, preserving the sounds but not the meaning of the original.

Contemporary popular culture

An epic science fiction adaptation/tribute by acclaimed author Dan Simmons titled Ilium was released in 2003. The novel received a Locus Award for best science fiction novel of 2003.

A loose film adaptation of the Iliad, Troy, was released in 2004. Though the film received mixed reviews, it was a commercial success, particularly in international sales. It grossed $133 million in the United States and $497 million worldwide, placing it in the 88th top-grossing movies of all time.[57]

Age of Bronze is an American comics series by writer/artist Eric Shanower retelling the legend of the Trojan War. It began in 1998 and is published by Image Comics.[58][59][60]

Published October 2011,[61] Alice Oswald's sixth collection, Memorial, is based on the Iliad but departs from the narrative form of the Iliad to focus on, and so commemorate, the individually-named characters whose deaths are mentioned in that poem.[62][63][64] Later in October 2011, Memorial was shortlisted for the T. S. Eliot Prize,[65] but in December 2011, Oswald withdrew the book from the shortlist,[66][67] citing concerns about the ethics of the prize's sponsors.[68]

English translations

George Chapman published his translation of the Iliad, in installments, beginning in 1598, published in "fourteeners", a long-line ballad metre that "has room for all of Homer's figures of speech and plenty of new ones, as well as explanations in parentheses. At its best, as in Achilles' rejection of the embassy in Iliad Nine; it has great rhetorical power".[69] It quickly established itself as a classic in English poetry. In the preface to his own translation, Pope praises "the daring fiery spirit" of Chapman's rendering, which is "something like what one might imagine Homer, himself, would have writ before he arrived at years of discretion".

John Keats praised Chapman in the sonnet On First Looking into Chapman's Homer (1816). John Ogilby's mid-seventeenth-century translation is among the early annotated editions; Alexander Pope's 1715 translation, in heroic couplet, is "The classic translation that was built on all the preceding versions",[70] and, like Chapman's, it is a major poetic work in its own right. William Cowper's Miltonic, blank verse 1791 edition is highly regarded for its greater fidelity to the Greek than either the Chapman or the Pope versions: "I have omitted nothing; I have invented nothing", Cowper says in prefacing his translation.

In the lectures On Translating Homer (1861), Matthew Arnold addresses the matters of translation and interpretation in rendering the Iliad to English; commenting upon the versions contemporarily available in 1861, he identifies the four essential poetic qualities of Homer to which the translator must do justice:

[i] that he is eminently rapid; [ii] that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is, both in his syntax and in his words; [iii] that he is eminently plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and, finally, [iv] that he is eminently noble.

After a discussion of the metres employed by previous translators, Arnold argues for a poetical dialect hexameter translation of the Iliad, like the original. "Laborious as this meter was, there were at least half a dozen attempts to translate the entire Iliad or Odyssey in hexameters; the last in 1945. Perhaps the most fluent of them was by J. Henry Dart [1862] in response to Arnold".[71] In 1870, the American poet William Cullen Bryant published a blank verse version, that Van Wyck Brooks describes as "simple, faithful".

An 1898 translation by Samuel Butler was published by Longmans. Butler had read Classics at Cambridge University, graduating during 1859.[72]

Since 1950, there have been several English translations. Richmond Lattimore's version (1951) is "a free six-beat" line-for-line rendering that explicitly eschews "poetical dialect" for "the plain English of today". It is literal, unlike older verse renderings. Robert Fitzgerald's version (Oxford World's Classics, 1974) strives to situate the Iliad in the musical forms of English poetry. His forceful version is freer, with shorter lines that increase the sense of swiftness and energy. Robert Fagles (Penguin Classics, 1990) and Stanley Lombardo (1997) are bolder than Lattimore in adding dramatic significance to Homer's conventional and formulaic language. Barry B. Powell's translation (Oxford University Press, 2014) renders the Homeric Greek with a simplicity and dignity reminiscent of the original.

Manuscripts

There are more than 2000 manuscripts of Homer.[73][74] Some of the most notable manuscripts include:

- Rom. Bibl. Nat. gr. 6 + Matriti. Bibl. Nat. 4626 from 870–890 AD

- Venetus A = Venetus Marc. 822 from the 10th century

- Venetus B = Venetus Marc. 821 from the 11th century

- Ambrosian Iliad

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 20

- Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 21

- Codex Nitriensis (palimpsest)

See also

Hellenismos portal

Hellenismos portal- Parallels between Virgil's Aeneid and Homer's Iliad and Odyssey

- Mask of Agamemnon

References

- ↑ "Iliad". Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary.

- ↑ Vidal-Naquet, Pierre. Le monde d'Homère (The World of Homer), Perrin (2000), p. 19

- ↑ "Linguistic evidence supports date for Homeric epics - Altschuler - 2013 - BioEssays - Wiley Online Library". Onlinelibrary.wiley.com. 2013-02-18. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. New York: Norton Books. p. 115.

- ↑ Lattimore, Richmond (2011). The Iliad of Homer. The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London: The University of Chicago Press. Book 1, Line number 155 (p. 79). ISBN 978-0-226-47049-8.

- ↑ Aeschylus does portray it so in Fragment 134a.

- ↑ Hornblower, S. and Spawforth, A. The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization (1998) pp. 3, 347, 352.

- ↑ Homer's Iliad, Classical Technology Center.

- ↑ Lefkowitz, Mary. Greek Gods, Human Lives: What We Can Learn From Myths (2003) New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press

- ↑ Taplin, Oliver. "Bring Back the Gods", The New York Times 14 December 2003.

- ↑ Jaynes, Julian. (1976) The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Pg. 221

- ↑ 2.155, 2.251, 9.413, 9.434, 9.622, 10.509, 16.82

- ↑ "The Concept of the Hero in Greek Civilization". Athome.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ "Heroes and the Homeric Iliad". Uh.edu. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- 1 2 Volk, Katharina. "ΚΛΕΟΣ ΑΦΘΙΤΟΝ Revisited". Classical Philology, Vol. 97, No. 1 (Jan., 2002), pp. 61–68.

- ↑ 9.410-416

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951)

- ↑ II.46, V.724, XIII.22, XIV.238, XVIII.370

- ↑ Rouse, W.H.D. The Iliad (1938) p.11

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.13.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad, Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.122.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 1.181–7.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 18.111–16.

- ↑ Fate as presented in Homer's "The Iliad", Everything2

- ↑ Iliad Study Guide, Brooklyn College Archived December 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.849–54.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.433–4.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 16.440–3.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 22.178–81.

- ↑ Homer. The Iliad. Richmond Lattimore, translator. Chicago: University of Chicago Press (1951). 20.300–4.

- ↑ Ἰλιάς, Ἰλιακός, Ἴλιος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ Hist. 2.116

- ↑ Robot Scans Ancient Manuscript in 3-D, Wired.

- ↑ Nikoletseas, Michael M. (2012). The Iliad: Twenty Centuries of Translation: A Critical View. ISBN 978-1469952109

- ↑ The Columbia Encyclopedia, Fifth Edition (1994) p.173

- ↑ Porter, John. The Iliad as Oral Formulaic Poetry (8 May 2006) University of Saskatchewan. Retrieved 26 November 2007.

- ↑ Lord, Albert. The Singer of Tales Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (1960) p.190

- ↑ Lord, Albert. The Singer of Tales Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press (1960) p.195

- ↑ Iliad, Book XVI, 130–54

- ↑ Armstrong, James I. The Arming Motif in the Iliad. The American Journal of Philology, Vol. 79, No. 4. (1958), pp.337–54.

- ↑ Toohey, Peter. Reading Epic: An Introduction to the Ancient Narrative. New Fetter Lane, London: Routledge, (1992).

- ↑ Iliad 3.45–50

- ↑ Iliad 59–65

- ↑ Keegan, John. A History of Warfare (1993) p.248

- ↑ Iliad 6.6

- ↑ Cahill, Tomas. Sailing the Wine Dark Sea: Why the Greeks Matter (2003)

- ↑ Lendon, J.E."Soldiers and Ghosts" (2005) p.36

- ↑ Lendon, J.E. "Soldiers and Ghosts" (2005) p. 22–3

- ↑ Iliad. 4.473-83, Lattimore, translator

- ↑ Lendon, J.E. "Soldiers and Ghosts" (2005) p.51

- ↑ 5.17

- ↑ (Iliad. 7.237-43, Lattimore, translator)

- ↑ Lendon, J.E. "Soldiers and Ghosts" (2005) p.240

- ↑ A large amount of the citations and argumentation in this section of the article must be ultimately attributed to:Lendon, J.E. Soldiers and Ghosts: A History of Battle in Classical Antiquity. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2005.

- ↑ Greek Warfare: Myth and Realities [Paperback] Hans Van Wees, p 249

- ↑ Bruce B. Lawrence and Aisha Karim (2008). On Violence: A Reader. Duke University Press. p. 377. ISBN 978-0-8223-3769-0.

- ↑ IMDB. "All Time Worldwide Box Office Grosses", Box Office Mojo

- ↑ A Thousand Ships (2001, ISBN 1-58240-200-0)

- ↑ Sacrifice (2004, ISBN 1-58240-360-0)

- ↑ Betrayal, Part One (2008, ISBN 978-1-58240-845-3)

- ↑ Oswald, Alice (2011). Memorial: An Excavation of the Iliad. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-27416-1.

- ↑ Holland, Tom (17 October 2011). "The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller / Memorial by Alice Oswald. Surfing the rip tide of all things Homeric.". The New Statesman. London: New Statesman. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Kellaway, Kate (2 October 2011). "Memorial by Alice Oswald – review". The Observer. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Higgins, Charlotte (28 October 2011). "The Song of Achilles by Madeline Miller, and more – review". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (20 October 2011). "TS Eliot prize 2011 shortlist revealed". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- ↑ Waters, Florence (6 December 2011). "Poet withdraws from TS Eliot prize over sponsorship". The Telegraph. London: Telegraph Media Group Limited. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (6 December 2011). "Alice Oswald withdraws from TS Eliot prize in protest at sponsor Aurum". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ Oswald, Alice (12 December 2011). "Why I pulled out of the TS Eliot poetry prize". The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Limited. Retrieved 2012-02-13.

- ↑ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.351

- ↑ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.352

- ↑ The Oxford Guide to English Literature in Translation, p.354

- ↑ St John's College - The Iliad (1898) Cambridge University [Retrieved 2016-06-16]

- ↑ OCLC 722287142

- ↑ Bird, Graeme D. (2010). Multitextuality in the Homeric Iliad: The Witness of the Ptolemaic Papyr. Washington, D.C.: Center for Hellenic Studies. ISBN 0-674-05323-0.

Bibliography

- Budimir, Milan (1940). On the Iliad and Its Poet.

- Mueller, Martin (1984). The Iliad. London: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 0-04-800027-2.

- Nagy, Gregory (1979). The Best of the Achaeans. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2388-9.

- Powell, Barry B. (2004). Homer. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-5325-6.

- Seaford, Richard (1994). Reciprocity and Ritual. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815036-9.

- West, Martin (1997). The East Face of Helicon. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815221-3.

- Fox, Robin Lane (2008). Travelling Heroes: Greeks and their myths in the epic age of Homer. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9980-8.

Further reading

- Murray, A.T.; Wyatt, William F., Homer: The Iliad, Books I-XII, Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, 1999, ISBN 978-0-674-99579-6

- Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume I, Books 1-4, Cambridge University Press, 1985. ISBN 0-521-23709-2

- Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume II, Books 5-8, Cambridge University Press, 1990. ISBN 0-521-23710-6

- Hainsworth, Bryan; Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume III, Books 9-12, Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-23711-4]

- Edwards, Mark W.; Janko, Richard; Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume IV, Books 13-16, Cambridge University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-521-28171-7

- Edwards, Mark W.; Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume V, Books 17–20, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-521-30959-X

- Richardson, Nicholas; Kirk, G.S., The Iliad: A Commentary: Volume VI, Books 21–24, Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 0-521-30960-3

- West, Martin L., Studies in the text and transmission of the Iliad, München : K.G. Saur, 2001. ISBN 3-598-73005-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Iliad. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- D. B. Monro, Homer: Iliad, Books I-XII, with an Introduction, a Brief Homeric Grammar, and Notes (3rd ed., 1890)

- D. B. Monro, Homer: Iliad, Books XIII-XXIV, with Notes (4th ed., 1903)

- D. B. Monro, A Grammar of the Homeric Dialect (2nd ed., 1891)

- Iliad : from the Perseus Project (PP), with the Murray and Butler translations and hyperlinks to mythological and grammatical commentary

- Gods, Achaeans and Troyans. An interactive visualization of The Iliad's characters flow and relations.

- The Iliad: A Study Guide

- Classical images illustrating the Iliad. Repertory of outstanding painted vases, wall paintings and other ancient iconography of the War of Troy.

- Comments on background, plot, themes, authorship, and translation issues by 2008 translator Herbert Jordan.

- Flaxman illustrations of the Iliad

- The Iliad study guide, themes, quotes, teacher resources

- The Iliad of Homer, Translated into English Blank Verse by William Cowper, edition c.1860. Online at Project Gutenberg.

- The Opening to the Iliad (Proem), Read in Ancient Greek with a simultaneous translation.

- The Iliad Map, map of locations in The Iliad

- Published English translations of Homer, with samples and some reviews by translator and scholar Ian Johnston

- Digital facsimile of the first printed publication (editio princeps) of the Iliad in Homeric Greek by Demetrios Chalkokondyles, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

-

The Iliad public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Iliad public domain audiobook at LibriVox