Okinawa Prefecture

| Okinawa Prefecture 沖縄県 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Prefecture | |||

| Japanese transcription(s) | |||

| • Japanese | 沖縄県 | ||

| • Rōmaji | Okinawa-ken | ||

| Okinawan transcription(s) | |||

| • Okinawan | 沖縄県(ウチナーチン) | ||

| • Rōmaji | Uchinaa-chin | ||

| |||

| |||

| Country | Japan | ||

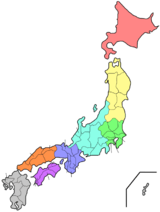

| Region | Kyushu | ||

| Island | Okinawa | ||

| Capital | Naha | ||

| Government | |||

| • Governor | Takeshi Onaga | ||

| Area | |||

| • Total | 2,271.30 km2 (876.95 sq mi) | ||

| Area rank | 44th | ||

| Population (October 1, 2013) | |||

| • Total | 1,416,587 | ||

| • Rank | 27th | ||

| • Density | 622/km2 (1,610/sq mi) | ||

| ISO 3166 code | JP-47 | ||

| Districts | 5 | ||

| Municipalities | 41 | ||

| Flower | Deego (Erythrina variegata) | ||

| Tree | Pinus luchuensis ("ryūkyūmatsu") | ||

| Bird | Okinawa woodpecker (Sapheopipo noguchii) | ||

| Fish | Banana fish (Caesio diagramma,"takasago", "gurukun") | ||

| Website |

www | ||

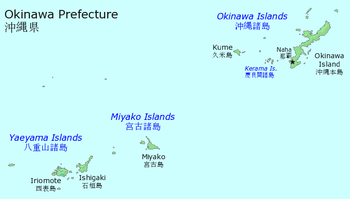

Okinawa Prefecture (Japanese: 沖縄県 Hepburn: Okinawa-ken, Okinawan: ウチナーチン Uchinaa-chin) is the southernmost prefecture of Japan.[1] It comprises hundreds of the Ryukyu Islands in a chain over 1,000 kilometres (620 mi) long. The Ryukyus extend southwest from Kyushu (the southwesternmost of Japan's four main islands) to Taiwan. The Okinawa Prefecture encompasses the southern two thirds of that chain. Naha, Okinawa's capital, is located in the southern part of Okinawa Island.[2] Currently about half of the 53,000 U.S. troops deployed in Japan as part of the post-WWII security arrangement are based in Okinawa.[3]

History

| History of Ryukyu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Periods

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Topics

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The oldest evidence of human existence on the Ryukyu islands is from the Stone Age and was discovered in Naha and Yaese.[4] Some human bone fragments from the Paleolithic era were unearthed, but there is no clear evidence of Paleolithic remains. Japanese Jōmon influences are dominant on the Okinawa Islands, although clay vessels on the Sakishima Islands have a commonality with those in Taiwan.

The first mention of the word Ryukyu was written in the Book of Sui. Okinawa was the Japanese word identifying the islands, first seen in the biography of Jianzhen, written in 779. Agricultural societies begun in the 8th century slowly developed until the 12th century. Since the islands are located at the eastern perimeter of the East China Sea relatively close to Japan, China and South-East Asia, the Ryukyu Kingdom became a prosperous trading nation. Also during this period, many Gusukus, similar to castles, were constructed. The Ryukyu Kingdom entered into the Imperial Chinese tributary system under the Ming dynasty beginning in the 15th century, which established economic relations between the two nations.

In 1609, the Shimazu clan, which controlled the region that is now Kagoshima Prefecture, invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom. The Ryukyu Kingdom was obliged to agree to form a suzerain-vassal relationship with the Satsuma and the Tokugawa shogunate, while maintaining its previous role within the Chinese tributary system; Ryukyuan sovereignty was maintained since complete annexation would have created a conflict with China. The Satsuma clan earned considerable profits from trade with China during a period in which foreign trade was heavily restricted by the shogunate.

Although Satsuma maintained strong influence over the islands, the Ryukyu Kingdom maintained a considerable degree of domestic political freedom for over two hundred years. Four years after the 1868 Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government, through military incursions, officially annexed the kingdom and renamed it Ryukyu han. At the time, the Qing Empire asserted a nominal suzerainty over the islands of the Ryukyu Kingdom, since the Ryūkyū Kingdom was also a member state of the Chinese tributary system. Ryukyu han became Okinawa Prefecture of Japan in 1879, even though all other hans had become prefectures of Japan in 1872. In 1912, Okinawans first obtained the right to vote for representatives to the national Diet which had been established in 1890.[5]

1945–1965

Near the end of World War II, in 1945, the US Army and Marine Corps invaded Okinawa with 185,000 troops. A third of the civilian population died;[6] a quarter of the civilian population died during the 1945 Battle of Okinawa alone.[7] The dead, of all nationalities, are commemorated at the Cornerstone of Peace. After the end of World War II in 1945 the Ryukyu independence movement developed, while Okinawa was under United States Military Government of the Ryukyu Islands administration for 27 years. During this "trusteeship rule", the United States established numerous military bases on the Ryukyu islands.

During the Korean War, B-29 Superfortresses flew bombing missions over Korea from Kadena Air Base on Okinawa. The military buildup on the island during the Cold War increased a division between local inhabitants and the American military. Under the 1952 Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan, the United States Forces Japan (USFJ) have maintained a large military presence.

Since 1960, the U.S. and Japan have maintained an agreement that allows the U.S. to secretly bring nuclear weapons into Japanese ports.[8] The Japanese tended to oppose the introduction of nuclear arms into Japanese territory by the government's assertion of Japan's non-nuclear policy and a statement of the Three Non-Nuclear Principles. Most of the weapons were alleged to be stored in ammunition bunkers at Kadena Air Base. Between 1954 and 1972, 19 different types of nuclear weapons were deployed in Okinawa, but with fewer than around 1,000 warheads at any one time.[9]

1965–1972 (Vietnam War)

Between 1965 and 1972, Okinawa was a key staging point for the United States in its military operations directed towards North Vietnam. Along with Guam, it presented a geographically strategic launch pad for covert bombing missions over Cambodia and Laos.[10] Anti-Vietnam War sentiment became linked politically to the movement for reversion of Okinawa to Japan. In 1965, the US military bases, earlier viewed as paternal post war protection, were increasingly seen as aggressive. The Vietnam War highlighted the differences between the United States and Okinawa, but showed a commonality between the islands and mainland Japan.[11]

As controversy grew regarding the alleged placement of nuclear weapons on Okinawa, fears intensified over the escalation of the Vietnam War. Okinawa was then perceived, by some inside Japan, as a potential target for China, should the communist government feel threatened by the United States.[12] American military secrecy blocked any local reporting on what was actually occurring at bases such as Kadena Air Base. As information leaked out, and images of air strikes were published, the local population began to fear the potential for retaliation.[11]

Political leaders such as Oda Makoto, a major figure in the Beheiren movement (Foundation of Citizens for Peace in Vietnam), believed, that the return of Okinawa to Japan would lead to the removal of U.S forces ending Japan's involvement in Vietnam.[13] In a speech delivered in 1967 Oda was critical of Prime Minister Sato’s unilateral support of America’s War in Vietnam claiming "Realistically we are all guilty of complicity in the Vietnam War".[13] The Beheiren became a more visible anti-war movement on Okinawa as the American involvement in Vietnam intensified. The movement employed tactics ranging from demonstrations, to handing leaflets to soldiers, sailors, airmen and marines directly, warning of the implications for a third World War.[14]

The US military bases on Okinawa became a focal point for anti-Vietnam War sentiment. By 1969, over 50,000 American military personnel were stationed on Okinawa,[15] accustomed to privileges and laws not shared by the indigenous population. The United States Department of Defense began referring to Okinawa as "The Keystone of the Pacific". This slogan was imprinted on local U.S military license plates.[16]

In 1969, chemical weapons leaked from the US storage depot at Chibana in central Okinawa, under the so-called Operation Red Hat. Evacuations of residents took place over a wide area for two months. Even two years later, government investigators found that Okinawans and the environment near the leak were still suffering because of the depot.[17]

In 1972, the U.S. government handed over the islands to Japanese administration.[18]

1973–2006

In a 1981 interview with the Mainichi Shimbun, Edwin O. Reischauer, former U.S. ambassador to Japan, said that U.S. naval ships armed with nuclear weapons stopped at Japanese ports on a routine duty, and this was approved by the Japanese government.

The 1995 Okinawa rape incident of a 12-year-old girl by U.S. servicemen triggered large protests in Okinawa. Reports by the local media of accidents and crimes committed by U.S. servicemen have reduced the local population's support for the U.S. military bases. A strong emotional response has emerged from certain incidents. As a result, the media has drawn renewed interest in the Ryukyu independence movement.

Documents declassified in 1997 proved that both tactical and strategic weapons have been maintained in Okinawa.[19][20] In 1999 and 2002, the Japan Times and the Okinawa Times reported speculation that not all weapons were removed from Okinawa.[21][22] On October 25, 2005, after a decade of negotiations, the governments of the US and Japan officially agreed to move Marine Corps Air Station Futenma from its location in the densely populated city of Ginowan to the more northerly and remote Camp Schwab in Nago by building a heliport with a shorter runway, partly on Camp Schwab land and partly running into the sea.[6] The move is partly an attempt to relieve tensions between the people of Okinawa and the Marine Corps.

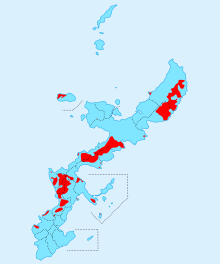

Okinawa prefecture constitutes 0.6% of Japan's land surface,[6] yet as of 2006, 75% of all USFJ bases were located on Okinawa, and U.S. military bases occupied 18% of the main island.[23]

2007–present

According to a 2007 Okinawa Times poll, 85% of Okinawans opposed the presence of the U.S. military,[24] because of noise pollution from military drills, the risk of aircraft accidents,[25] environmental degradation,[26] and crowding from the number of personnel there,[27] although 73.4% of Japanese citizens appreciated the mutual security treaty with the U.S. and the presence of the USFJ.[28] In another poll conducted by the Asahi Shimbun in May 2010, 43% of the Okinawan population wanted the complete closure of the U.S. bases, 42% wanted reduction and 11% wanted the maintenance of the status quo.[29]

In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a young girl of 14 by a Marine on Okinawa. The U.S. military also imposed a temporary 24-hour curfew on military personnel and their families to ease the anger of local residents.[30] Some cited statistics that the crime rate of military personnel is consistently less than that of the general Okinawan population.[31] However, some criticized the statistics as unreliable, since violence against women is under-reported.[32]

Between 1972 and 2009, U.S. servicemen committed 5,634 criminal offenses, including 25 murders, 385 burglaries, 25 arsons, 127 rapes, 306 assaults and 2,827 thefts.[7]

In 2009 a new Japanese government came to power and froze the US forces relocation plan, but in April 2010 indicated their interest in resolving the issue by proposing a modified plan.[33] Okinawan feelings about the U.S. military are complex, and some of the resentment towards the U.S. bases is directed towards the government in Tokyo, perceived as being insensitive to Okinawan needs and using Okinawa to house bases not desired elsewhere in Japan. Okinawa is the poorest prefecture within Japan, and the issue of U.S. bases has become tangled with the sense of colonialist/imperialist treatment of Okinawa by Tokyo.

A study done in 2010 by Rupert Cox found that the prolonged exposure to aircraft noise around the Kadena Air Base and other military bases cause health issues such as a disrupted sleep pattern, high blood pressure, weakening of the immune system in children, and a loss of hearing.[34]

In 2011, it was reported that the U.S. military—contrary to repeated denials by the Pentagon—had kept tens of thousands of barrels of Agent Orange on the island. The Japanese and American governments have angered some U.S. veterans, who believe they were poisoned by Agent Orange while serving on the island, by characterizing their statements regarding Agent Orange as "dubious", and ignoring their requests for compensation. Reports that more than a third of the barrels developed leaks have led Okinawans to ask for environmental investigations, but as of 2012 both Tokyo and Washington refused such action.[35] Jon Mitchell has reported concern that the U.S. used American Marines as chemical-agent guinea pigs.[36]

A 2012 book, Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States, argues that the U.S. presence on Okinawa, which has provoked strong opposition and resistance among the island's inhabitants, is not geared towards defending Japan, but rather to serve as part of an American forward deployment strategy aimed at Southeast Asia and China, the stability of which is not important to Japanese commercial or defense interests.[37]

27,000 personnel, including 15,000 Marines, contingents from the Navy, Army and Air Force, and their 22,000 family members are stationed in Okinawa.[38]

Marine Corps Air Station Futenma relocation, 2006–present

As of December 2014, one ongoing issue is the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma. First promised to be moved off the island and then later within the island, as of November 2014 the future of any relocation is uncertain with the election of base-opponent Onaga as Okinawa governor.[39] Onaga won against the incumbent Nakaima who had earlier approved landfill work to move the base to Camp Schwab in Henoko. However, Onaga has promised to veto the landfill work needed for the new base to be built and insisted Futenma should be moved outside of Okinawa.[40]

As of 2006, some 8,000 U.S. Marines were removed from the island and relocated to Guam.[41] In November 2008, U.S. Pacific Command Commander Admiral Timothy Keating stated the move to Guam would probably not be completed before 2015.[42]

In 2009 Japan's former foreign minister Katsuya Okada stated that he wanted to review the deployment of U.S. troops in Japan to ease the burden on the people of Okinawa (Associated Press, October 7, 2009) 5,000 of 9,000 Marines will be deployed at Guam and the rest will be deployed at Hawaii and Australia. Japan will pay $3.1 billion cash for the moving and for developing joint training ranges on Guam and on Tinian and Pagan in the U.S.-controlled Northern Mariana Islands.[43][44][45]

As of 2014 the US still maintains Air Force, Marine, Navy, and Army military installations on the islands. These bases include Kadena Air Base, Camp Foster, Marine Corps Air Station Futenma, Camp Hansen, Camp Schwab, Torii Station, Camp Kinser, and Camp Gonsalves. The area of 14 U.S. bases are 233 square kilometres (90 sq mi), occupying 18% of the main island. Okinawa hosts about two-thirds of the 50,000 American forces in Japan although the islands account for less than one percent of total lands in Japan.[23]

Suburbs have grown towards and now surround two historic major bases, Futenma and Kadena. One third (9,852 acres (39.87 km2)) of the land used by the U.S. military is the Marine Corps Northern Training Area (known also as Camp Gonsalves or JWTC) in the north of the island.[46]

Helipads construction in Takae and Yanbaru

Since the early 2000s, Okinawans have opposed the presence of American troops helipads in the Takae zone of the Yanbaru forest near Higashi and Kunigami.[47] This opposition has increased particularly in July 2016 against the construction of six new helipads.[48][49]

Geography

Major islands

The islands comprising the prefecture are the southern two thirds of the archipelago of the Ryūkyū Islands (琉球諸島 Ryūkyū-shotō). Okinawa's inhabited islands are typically divided into three geographical archipelagos. From northeast to southwest:

- Okinawa Islands (沖縄諸島 Okinawa Shotō)

- Miyako Islands

- Yaeyama Islands

Cities

Eleven cities are located within the Okinawa Prefecture. Okinawan names are in parentheses:

|

|

Towns and villages

These are the towns and villages in each district:

Town mergers

Natural parks

As of March 31, 2008, 19% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely the Iriomote-Ishigaki National Park; Okinawa Kaigan and Okinawa Senseki Quasi-National Parks; and Irabu, Kumejima, and Tonaki Prefectural Natural Parks.[50]

Fauna

The dugong is an endangered marine mammal related to the manatee.[51] Iriomote is home to one of the world's rarest and most endangered cat species, the Iriomote cat. The region is also home to at least one endemic pit viper, Trimeresurus elegans. Coral reefs found in this region of Japan provide an environment for a diverse marine fauna. The sea turtles return yearly to the southern islands of Okinawa to lay their eggs. The summer months carry warnings to swimmers regarding venomous jellyfish and other dangerous sea creatures.

Flora

Okinawa is a major producer of sugar cane, pineapple, papaya, and other tropical fruit, and the Southeast Botanical Gardens represent tropical plant species.

Geology

The island is largely composed of coral, and rainwater filtering through that coral has given the island many caves, which played an important role in the Battle of Okinawa. Gyokusendo[52] is an extensive limestone cave in the southern part of Okinawa's main island.

Climate

The island experiences temperatures above 20 °C (68 °F) for most of the year. The climate of the islands ranges from humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa) in the north, such as Okinawa Island, to tropical rainforest climate (Köppen climate classification Af) in the south such as Iriomote Island. The islands of Okinawa are surrounded by some of the most abundant coral reefs found in the world.[53][54] The world's largest colony of rare blue coral is found off of Ishigaki Island.[55] Snowfall is unheard of at sea level. However, on January 24, 2016, sleet was reported in Nago on Okinawa Island for the first time on record.[56]

Demography

Okinawa prefecture age pyramid as of October 1, 2003[57]

(per thousands of people)

| Age | People |

|---|---|

| 0–4 | |

| 5–9 | |

| 10–14 | |

| 15–19 | |

| 20–24 | |

| 25–29 | |

| 30–34 | |

| 35–39 | |

| 40–44 | |

| 45–49 | |

| 50–54 | |

| 55–59 | |

| 60–64 | |

| 65–69 | |

| 70–74 | |

| 75–79 | |

| 80 + |

Okinawa Prefecture age pyramid, divided by sex, as of October 1, 2003

(per thousands of people)

| Males | Age | Females |

|---|---|---|

| 43 |

0–4 | |

| 44 |

5–9 | |

| 45 |

10–14 | |

| 48 |

15–19 | |

| 46 |

20–24 | |

| 49 |

25–29 | |

| 49 |

30–34 | |

| 43 |

35–39 | |

| 46 |

40–44 | |

| 49 |

45–49 | |

| 52 |

50–54 | |

| 32 |

55–59 | |

| 32 |

60–64 | |

| 32 |

65–69 | |

| 24 |

70–74 | |

| 14 |

75–79 | |

| 17 |

80 + |

Language and culture

Having historically been a separate nation until 1879, Okinawan language and culture differ in many ways from that of mainland Japan.

Language

There remain six Ryukyuan languages which are incomprehensible to Japanese speakers, although they are considered to make up the family of Japonic languages along with Japanese. These languages are in decline as Standard Japanese is being used by the younger generation. They are generally perceived as "dialects" by mainland Japanese and some Okinawans themselves. Standard Japanese is almost always used in formal situations. In informal situations, de facto everyday language among Okinawans under age 60 is Okinawa-accented mainland Japanese ("Okinawan Japanese"), which is often misunderstood as Okinawan language proper. The actual traditional Okinawan language is still used in traditional cultural activities, such as folk music and folk dance. There is a radio news program in the language as well.[58]

Religion

Okinawans have traditionally followed Ryukyuan religious beliefs, generally characterized by ancestor worship and the respecting of relationships between the living, the dead, and the gods and spirits of the natural world.[59]

Cultural influences

Okinawan culture bears traces of its various trading partners. One can find Chinese, Thai and Austronesian influences in the island's customs. Perhaps Okinawa's most famous cultural export is karate, probably a product of the close ties with and influence of China on Okinawan culture. Karate is thought to be a synthesis of Chinese kung fu with traditional Okinawan martial arts. A ban on weapons in Okinawa for two long periods after the formal annexation of the islands and abolition of the kingdom in 1879 by Japan during the Meiji Restoration period also very likely contributed to its development. Okinawans' reputation as wily resisters of being influenced by conquerors is depicted in the 1956 Hollywood film, The Teahouse of the August Moon, which takes place immediately after World War II.

Another traditional Okinawan product that owes its existence to Okinawa's trading history is awamori—an Okinawan distilled spirit made from indica rice imported from Thailand.

Other cultural characteristics

Other prominent examples of Okinawan culture include the sanshin—a three-stringed Okinawan instrument, closely related to the Chinese sanxian, and ancestor of the Japanese shamisen, somewhat similar to a banjo. Its body is often bound with snakeskin (from pythons, imported from elsewhere in Asia, rather than from Okinawa's venomous Trimeresurus flavoviridis, which are too small for this purpose). Okinawan culture also features the eisa dance, a traditional drumming dance. A traditional craft, the fabric named bingata, is made in workshops on the main island and elsewhere.

The Okinawan diet consist of low-fat, low-salt foods, such as whole fruits and vegetables, legumes, tofu, and seaweed. Okinawans are known for their longevity. This particular island is a so-called Blue Zone, an area where the people live longer than most others elsewhere in the world. Five times as many Okinawans live to be 100 as in the rest of Japan, and Japanese are already the longest-lived ethnic group globally.[60] As of 2002 there were 34.7 centenarians for every 100,000 inhabitants, which is the highest ratio worldwide.[61]:131–132 Possible explanations are diet, low-stress lifestyle, caring community, activity, and spirituality of the inhabitants of the island.[61]

A cultural feature of the Okinawans is the forming of moais. A moai is a community social gathering and groups that come together to provide financial and emotional support through emotional bonding, advice giving, and social funding. This provides a sense of security for the community members and as mentioned in the Blue Zone studies, may be a contributing factor to the longevity of its people.[62]

In recent years, Okinawan literature has been appreciated outside of the Ryukyu archipelago. Two Okinawan writers have received the Akutagawa Prize: Matayoshi Eiki in 1995 for The Pig's Retribution (豚の報い Buta no mukui) and Medoruma Shun in 1997 for A Drop of Water (Suiteki). The prize was also won by Okinawans in 1967 by Tatsuhiro Oshiro for Cocktail Party (Kakuteru Pāti) and in 1971 by Mineo Higashi for Okinawan Boy (Okinawa no Shōnen).[63][64]

Karate

Karate originated in Okinawa. Over time, it developed into several styles and sub-styles. On Okinawa, the three main styles are considered to be Shorin-Ryu, Gōjū-ryū and Uechi-Ryu. Internationally, the various styles and sub-styles include Matsubayashi Ryu, Wado Ryu, Isshin-Ryu, Shotokan, Shito-Ryu, Shorinjiryu Kenkokan, Shorinjiryu Koshinkai, Shorinji Ryu, and Shuri-ryū.

Architecture

Despite widespread destruction during World War II, there are many remains of a unique type of castle or fortress known as gusuku; the most significant are now inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List (Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu).[65] In addition, twenty-one Ryukyuan architectural complexes and thirty-six historic sites have been designated for protection by the national government.[66]

Whereas most homes in Japan are made from wood and allow free-flow of air to combat humidity, typical modern homes in Okinawa are made from concrete with barred windows to protect from flying plant debris and to withstand regular typhoons. Roofs are designed with strong winds in mind, where each tile is cemented on and not merely layered as seen with many homes elsewhere in Japan.

Many roofs also display a statue resembling a lion or dragon, called a shisa, which is said to protect the home from danger. Roofs are typically red in color and are inspired by Chinese design.

Education

The public schools in Okinawa are overseen by the Okinawa Prefectural Board of Education. The agency directly operates several public high schools.[67] The U.S. Department of Defense Dependents Schools (DoDDS) operates 13 schools total in Okinawa. Seven of these schools are located on Kadena Air Base.

Okinawa has many types of private schools. Some of them are cram schools, also known as juku. Others, such as Nova, solely teach language. People also attend small language schools.

There are 10 colleges/universities in Okinawa, including the University of the Ryukyus, the only national university in the prefecture, and the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology, a new international research institute. Okinawa's American military bases also host the Asian Division of the University of Maryland University College.

Sports

- Association football

- Basketball

In addition, various baseball teams hold training during the winter in the prefecture as it is the warmest prefecture of Japan with no snow and higher temperatures than other prefectures.

There are numerous golf courses in the prefecture, and there was formerly a professional tournament called the Okinawa Open.

Transportation

Air transportation

- Aguni Airport

- Hateruma Airport

- Iejima Airport

- New Ishigaki Airport

- Kerama Airport

- Kita Daito Airport

- Kumejima Airport

- Minami-Daito Airport

- Miyako Airport

- Naha Airport

- Shimojijima Airport

- Tarama Airport

- Yonaguni Airport

Highways

- Okinawa Expressway

- Naha Airport Expressway

- Route 58

- Route 329

- Route 330

- Route 331

- Route 332

- Route 390

- Route 449

- Route 505

- Route 506

- Route 507

Rail

Ports

The major ports of Okinawa include:

- Naha Port[69]

- Port of Unten[70]

- Port of Kinwan[71]

- Nakagusukuwan Port[72]

- Hirara Port[73]

- Port of Ishigaki[74]

Economy

The 34 US military installations on Okinawa are financially supported by the U.S. and Japan.[75] The bases provide jobs for Okinawans, both directly and indirectly; In 2011, the U.S. military employed over 9,800 Japanese workers in Okinawa.[75] As of 2012 the bases accounted for 4 or 5% of the economy.[76] However, Koji Taira argued in 1997 that because the U.S. bases occupy around 20% of Okinawa's land, they impose a deadweight loss of 15% on the Okinawan economy.[77] The Tokyo government also pays the prefectural government around ¥10 billion per year[75] in compensation for the American presence, including, for instance, rent paid by the Japanese government to the Okinawans on whose land American bases are situated.[78] A 2005 report by the U.S. Forces Japan Okinawa Area Field Office estimated that in 2003 the combined U.S. and Japanese base-related spending contributed $1.9 billion to the local economy.[79] On January 13, 2015, In response to the citizens electing governor Takeshi Onaga, the national government announced that Okinawa's funding will be cut, due to the governor's stance on removing the US military bases from Okinawa, which the national government doesn't want happening.[80][81]

The Okinawa Convention and Visitors Bureau is exploring the possibility of using facilities on the military bases for large-scale Meetings, incentives, conferencing, exhibitions events.[82]

Military

United States military installations

- United States Marine Corps

- Marine Corps Base Camp Smedley D. Butler

- Camp Foster

- Marine Corps Air Station Futenma

- Camp Kinser

- Camp Courtney

- Camp McTureous

- Camp Hansen

- Camp Schwab

- Camp Gonsalves (Jungle Warfare Training Center)

- United States Air Force

- United States Navy

- Camp Lester (Camp Kuwae)[83]

- Camp Shields

- Naval Facility White Beach

- United States Army

Notable people

- Ryan Higa, Youtuber

- Chōjun Miyagi founder of Gōjū-ryū, "hard/soft" style of famous Okinawan Karate.

- Uechi Kanbun was the founder of Uechi-ryū, one of the primary karate styles of Okinawa.

- Mitsuru Ushijima was the Japanese general at the Battle of Okinawa, during the final stages of World War II.

- Isamu Chō was an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army known for his support of ultranationalist politics and involvement in a number of attempted military and right-wing coup d'états in pre-World War II Japan.

- Ota Minoru was an admiral in the Imperial Japanese Navy during World War II, and the final commander of the Japanese naval forces defending the Oroku Peninsula during the Battle of Okinawa.

- Sato Eisaku was a Japanese politician and the 61st, 62nd and 63rd Prime Minister of Japan. While he was premier in 1972, Okinawa was returned to Japan.

- Yabu Kentsu was a prominent teacher of Shōrin-ryū karate in Okinawa from the 1910s until the 1930s, and was among the first people to demonstrate karate in Hawaii.

- Takuji Iwasaki was a meteorologist, biologist, ethnologist historian.

- Matayoshi Eiki Okinawan novel writer, winner of Akutagawa prize

- Gackt Japanese pop rock singer-songwriter, actor, author

- Namie Amuro Japanese R&B, hip hop and pop singer

- Beni Japanese pop and R&B singer

- Ben Shepherd Bassist of the band Soundgarden

- Orange Range Japanese rock band

- Stereopony Japanese all-female pop rock band

- Tamlyn Tomita actress and singer

- Rino Nakasone Razalan professional dancer and choreographer.

- Yukie Nakama singer, musician and actress

- Daichi Miura Japanese pop singer, dancer and choreographer.

- Yui Aragaki actress, singer, and model

- Hearts Grow Japanese band

- Aisa Senda, Japanese singer, actress and TV presenter in Taiwan

- Robert Griffin III, American football quarterback, Heisman Trophy winner

- Dave Roberts, Major League Baseball player and manager

See also

- Okinawa Prefectural Assembly

- Okinawan Americans

- Pechin – Ryukyu (Okinawan) Samurai

- People from Okinawa Prefecture

- Ryukyuan people

References

- ↑ Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Okinawa-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 746-747, p. 746, at Google Books

- ↑ Nussbaum, "Naha" in p. 686, p. 686, at Google Books

- ↑ 'Under a decades-old security alliance, Okinawa hosts about 26,000 U.S. service personnel, more than half the total Washington keeps in all of Japan, in addition to base workers and family members.' "U.S. civilian arrested in fresh Okinawa DUI case; man injured". The Japan Times. July 2016.

- ↑ 山下町第1洞穴出土の旧石器について Archived October 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.(Japanese), 南島考古22

- ↑ Steve Rabson, "Meiji Assimilation Policy in Okinawa: Promotion, Resistance, and "Reconstruction" in New Directions in the Study of Meiji Japan (Helen Hardacre, ed.). Brill, 1997. p. 642.

- 1 2 3 "No home where the dugong roam". The Economist. October 27, 2005.

- 1 2 David Hearst (March 11, 2011). "Second battle of Okinawa looms as China's naval ambition grows". The Guardian. UK.

- ↑ New Documents On Okinawa Reversion

- ↑ Norris, Robert S.; Arkin, William M.; Burr, William (November 1999). "Where They Were" (PDF). Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 55 (6): 26–35. doi:10.2968/055006011.

- ↑ John Morrocco. Rain of Fire. (United States: Boston Publishing Company), pg 14

- 1 2 ROBERT TRUMBULL (1 August 1965). "OKINAWA B-52'S ANGER JAPANESE: Bombing of Vietnam From Island Stirs Public Outcry.". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 September 2009.

- ↑ Mori, Kyozo, Two Ends of a Telescope Japanese and American Views of Okinawa, Japan Quarterly, 15:1 (1968:Jan./Mar.) p.17

- 1 2 Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 120

- ↑ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Pg 123

- ↑ Christopher T. Sanders (2000) America’s Overseas Garrisons the Leasehold Empire Oxford University Press PG 164

- ↑ Havens, T. R. H. (1987) Fire Across the Sea: The Vietnam War and Japan, 1965–1975. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press Pg 88

- ↑ Steve Rabson. "Okinawa's Henoko was a 'Storage Location' for Nuclear Weapons: Published Accounts". The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus. 11 (1( 6)). Retrieved 14 January 2012.

- ↑ Reversion to Japan of the Ryukyu and Daito Islands, official text. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ Steve Rabson (January 14, 2013). "Okinawa's Henoko was a "storage location" for nuclear weapons:". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Retrieved April 25, 2013.

- ↑ Japanese government reveals secret nuclear agreement with the US, Chan, John., World Socialist Web Site Retrieved March 24, 2010

- ↑ "News". The Japan Times. May 15, 2002.

- ↑ 疑惑が晴れるのはいつか(Japanese), Okinawa Times, May 16, 1999

- 1 2 沖縄に所在する在日米軍施設・区域(Japanese), Japan Ministry of Defense

- ↑ "沖縄タイムス社説 2007.5.13". Retrieved June 1, 2016.. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ one in 1959 killed 17 people

- ↑ Impact on the Lives of the Okinawan People (Incidents, Accidents and Environmental Issues) Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine., Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ↑ 沖縄・米兵による女性への性犯罪(Rapes and murders by the U.S. military personnel 1945–2000)(Japanese), 基地・軍隊を許さない行動する女たちの会 Archived January 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 自衛隊・防衛問題に関する世論調査 Archived October 22, 2010, at the Wayback Machine., The Cabinet Office of Japan

- ↑ Archived May 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Justin McCurry (February 28, 2008). "Rice says sorry for US troop behaviour on Okinawa as crimes shake alliance with Japan". The Guardian. UK.

- ↑ MICHAEL HASSETT (February 26, 2008). "U.S. military crime: SOFA so good?The stats offer some surprises in wake of the latest Okinawa rape claim". The Japan Times.

- ↑ "Okinawa: Effects of long-term US Military presence" (PDF).

- ↑ Pomfret, John (April 24, 2010). "Japan moves to settle dispute with U.S. over Okinawa base relocation". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Cox, Rupert (2010-12-01). "The Sound of Freedom: US Military Aircraft Noise in Okinawa, Japan". Anthropology News. 51 (9): 13–14. doi:10.1111/j.1556-3502.2010.51913.x. ISSN 1556-3502.

- ↑ Jon Mitchell, "Agent Orange on Okinawa – The Smoking Gun: U.S. army report, photographs show 25,000 barrels on island in early '70s", The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 11, Issue 1, No. 6, January 14, 2012.

- ↑ Jon Mitchell, "Were U.S marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?" The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol 10, Issue 51, No. 2, December 17, 2012.

- ↑ McCormack, Gavan; Norimatsu, Satoko Oka (2012). Resistant Islands: Okinawa Confronts Japan and the United States. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 1442215623.

- ↑ 沖縄県の基地の現状(Japanese), Okinawa Prefectural Government

- ↑ "Okinawa US base move in doubt after governor elections". BBC. 16 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ "U.S. base relocation opponent elected Okinawan governor". Japan Today. 17 November 2014. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Steven Donald Smith (April 26, 2006). "Eight Thousand U.S. Marines to Move From Okinawa to Guam". American Forces Press Service. DOD. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ↑ "Marines' Exit May Take Till '15: U.S.". Kyodo News. Japan Times. 9 November 2008.

- ↑ "U.S., Japan unveil revised plan for Okinawa". April 27, 2012.

- ↑ "US Okinawa Reductions". globalsecurity.orgdate=June 23, 2013.

- ↑ http://www.japan-press.co.jp/2009/2644/USF4.html

- ↑ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/life/2012/08/19/travel/rumbles-in-the-jungle/#.V53t7COLTZs

- ↑ http://okinawa-takae.org/index.php/takaes-story/

- ↑ http://english.ryukyushimpo.jp/2016/07/17/25465/

- ↑ http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/07/22/national/politics-diplomacy/central-government-sues-okinawa-futenma-relocation/

- ↑ "General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture" (PDF). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved February 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Lawsuit Seeks to Halt Construction of U.S. Military Airstrip in Japan That Would Destroy Habitat of Endangered Okinawa Dugongs". Center for Biological Diversity. 31 July 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ↑ "Gyokusendo Cave". Japan-guide.com. 2013-05-29. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ "Establishing World-Class Coral Reef Ecosystem Monitoring in Okinawa". Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ "Coral Reefs". Okinawa Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ "Heliopora coerulea". International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ "沖縄本島で観測史上初のみぞれ 名護". The Asahi Shimbun Company. 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2016-02-20.

- ↑ Jinsui, Japan: Statistics Bureau (総務省 統計局), 2003

- ↑ おきなわBBtv★沖縄の方言ニュース★沖縄の「今」を沖縄の「言葉」で!ラジオ沖縄で好評放送中の「方言ニュース」をブロードバンドでお届けします。. Okinawabbtv.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Okinawa Prefectural reserve cultural assets center (2006). "陶磁器から古の神事(祭祀・儀式)を考える". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ↑ National Geographic magazine, June 1993

- 1 2 Santrock, John W. A (2002). Topical Approach to Life-Span Development (4 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill.

- ↑ "Okinawa's Longevity Lessons". Blue Zones. Admin. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- ↑ "Okinawa Writers Excel in Literature". The Okinawa Times. Okinawa Times. July 21, 2000. Archived from the original on August 23, 2000. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ↑ 芥川賞受賞者一覧 (in Japanese). Bungeishunju Ltd. 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu". UNESCO. Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Database of National Cultural Properties: 国宝・重要文化財 (建造物): 沖縄県" (in Japanese). Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved May 20, 2012.

- ↑ Archived January 21, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Ryukyu Corazon". Ryukyu Corazon. Retrieved 2014-08-05.

- ↑ Naha port. Nahaport.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ (Japanese) 運天港. Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ (Japanese) 金武湾港. Pref.okinawa.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ 沖縄総合事務局 那覇港湾・空港整備事務所 中城湾港出張所. Dc.ogb.go.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ 平良港湾事務所. Dc.ogb.go.jp. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Archived January 15, 2013, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 Stephen Nessen (4 January 2011). "Okinawa U.S. Marine Base Angers Residents And Governor". Retrieved 19 August 2014.

- ↑ Hongo, Jun. (2012-05-16) Economic reliance on bases won't last, trends suggest. The Japan Times. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Taira, Koji (1997). 'The Okinawan Charade' Japan Policy Research Institute, Working Paper No. 28

- ↑ The Okinawa Solution Archived June 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.. G2mil.com. Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- ↑ Eric Johnston (28 March 2006). "Okinawa base issue not cut and dried with locals". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ Isabel Reynolds; Maiko Takahashi (January 13, 2015). "Japan cuts Okinawa budget after election of Anti-base governor". Retrieved 21 November 2014.

- ↑ "Gov't cuts budget for Okinawa economic development". January 15, 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- ↑ "Okinawa looks to offer more unique venues". TTGmice. September 6, 2012. Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Camp Lester (Camp Kuwae). Globalsecurity.org (1996-12-02). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Okinawa Prefecture. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Okinawa. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Okinawa. |

News

- Okinawa's Virtual Ginza, News, Information, and unique insight on Okinawa and its culture. (Updated frequently)

- Okinawa 1988–1991 Blog, reporting news about Okinawa.

- Okinawa plants

- Okinawa marine life

- Okinawa News and Ads Keeping people together and informed

Photographs

- Okinawa pictures Pictures of Okinawa Japan shot as HDR photography by Okinawa Living Magazine's Art Director.

- Okinawa Japan Pictures Okinawa Japan photography group

Culture

- Ryukyu Cultural Archives

- Okinawa Prefecture Official Home-page

- The Okinawa Centenarian Study

- Okinawa Web Radio(BRAZIL)

History

- History and Photos from the United States Administration Period 1945 to 1972

- Images of Okinawa after World War II color slides were taken between 1945 and 1946

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties

Miscellany

- Internships & Japanese language school in Okinawa

- The Contemporary Okinawa Website – History, culture, news, book reviews, historical documents, links, opinions

- Okinawa Geocaching – site for geocaching (treasure hunt with GPS) in Okinawa.

- Call of Duty game – Okinawa is featured in the video game Call of Duty: World at War

- Call of Duty game – Okinawa is featured in the video game Call of Duty: Heroes

Peace

- Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum

- Okinawa Peace Network of Los Angeles – Useful information on the U.S. military base controversy.

Coordinates: 26°30′N 128°0′E / 26.500°N 128.000°E