Conscription

| Conscription |

|---|

|

Military service |

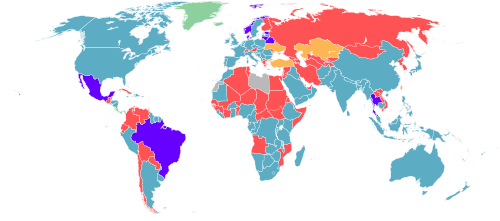

| Conscription by country |

Conscription, or drafting, is the compulsory enlistment of people in a national service, most often a military service.[1] Conscription dates back to antiquity and continues in some countries to the present day under various names. The modern system of near-universal national conscription for young men dates to the French Revolution in the 1790s, where it became the basis of a very large and powerful military. Most European nations later copied the system in peacetime, so that men at a certain age would serve 1–8 years on active duty and then transfer to the reserve force.

Conscription is controversial for a range of reasons, including conscientious objection to military engagements on religious or philosophical grounds; political objection, for example to service for a disliked government or unpopular war; and ideological objection, for example, to a perceived violation of individual rights. Those conscripted may evade service, sometimes by leaving the country.[7] Some selection systems accommodate these attitudes by providing alternative service outside combat-operations roles or even outside the military, such as 'Siviilipalvelus' (civil service) in Finland, Zivildienst (civil service) in Austria and Switzerland. Most post-Soviet countries conscript soldiers not only for Armed Forces but also for paramilitary organizations which are dedicated to police-like domestic only service (Internal Troops) or non-combat rescue duties (Civil Defence Troops) – none of which is considered alternative to the military conscription.

As of the early 21st century, many states no longer conscript soldiers, relying instead upon professional militaries with volunteers enlisted to meet the demand for troops. The ability to rely on such an arrangement, however, presupposes some degree of predictability with regard to both war-fighting requirements and the scope of hostilities. Many states that have abolished conscription therefore still reserve the power to resume it during wartime or times of crisis.[8]

History

In pre-modern times

Ilkum

Around the reign of Hammurabi (1791–1750 BC), the Babylonian Empire used a system of conscription called Ilkum. Under that system those eligible were required to serve in the royal army in time of war.[9] During times of peace they were instead required to provide labour for other activities of the state.[9] In return for this service, people subject to it gained the right to hold land.[9] It is possible that this right was not to hold land per se but specific land supplied by the state.[9]

Various forms of avoiding military service are recorded. While it was outlawed by the Code of Hammurabi, the hiring of substitutes appears to have been practiced both before and after the creation of the code.[10] Later records show that Ilkum commitments could become regularly traded.[10] In other places, people simply left their towns to avoid their Ilkum service.[10] Another option was to sell Ilkum lands and the commitments along with them. With the exception of a few exempted classes, this was forbidden by the Code of Hammurabi.[10]

Medieval levies

Under the feudal conditions for holding land in the medieval period, most peasants and freemen were liable to provide one man of suitable age per family for military duty when required by either the king or the local lord. The levies raised in this way fought as infantry under local superiors. Although the exact laws varied greatly depending on the country and the period, generally these levies were only obliged to fight for one to three months. Most were subsistence farmers, and it was in everyone's interest to send the men home for harvest-time.

In medieval Scandinavia the leiðangr (Old Norse), leidang (Norwegian), leding, (Danish), ledung (Swedish), lichting (Dutch), expeditio (Latin) or sometimes leþing (Old English), was a levy of free farmers conscripted into coastal fleets for seasonal excursions and in defence of the realm.

The bulk of the Anglo-Saxon English army, called the fyrd, was composed of part-time English soldiers drawn from the landowning minor nobility. These thegns were the land-holding aristocracy of the time and were required to serve with their own armour and weapons for a certain number of days each year. The historian David Sturdy has cautioned about regarding the fyrd as a precursor to a modern national army composed of all ranks of society, describing it as a "ridiculous fantasy":

The persistent old belief that peasants and small farmers gathered to form a national army or fyrd is a strange delusion dreamt up by antiquarians in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth centuries to justify universal military conscription.[11]

Medieval levy in Poland was known as the pospolite ruszenie.

Military slavery

The system of military slaves was widely used in the Middle East, beginning with the creation of the corps of Turkish slave-soldiers (ghulams or mamluks) by the Abbasid caliph al-Mu'tasim in the 820s and 830s. The Turkish troops soon came to dominate the government, establishing a pattern throughout the Islamic world of a ruling military class, often separated by ethnicity, culture and even religion by the mass of the population, a paradigm that found its apogee in the Mamluks of Egypt and the Janissary corps of the Ottoman Empire, institutions that survived until the early 19th century.

In the middle of the 14th century, Ottoman Sultan Murad I developed personal troops to be loyal to him, with a slave army called the Kapıkulu. The new force was built by taking Christian children from newly conquered lands, especially from the far areas of his empire, in a system known as the devşirme (translated "gathering" or "converting"). The captive children were forced to convert to Islam. The Sultans had the young boys trained over several years. Those who showed special promise in fighting skills were trained in advanced warrior skills, put into the sultan's personal service, and turned into the Janissaries, the elite branch of the Kapıkulu. A number of distinguished military commanders of the Ottomans, and most of the imperial administrators and upper-level officials of the Empire, such as Pargalı İbrahim Pasha and Sokollu Mehmet Paşa, were recruited in this way.[12] By 1609, the Sultan's Kapıkulu forces increased to about 100,000.[13]

In later years, Sultans turned to the Barbary Pirates to supply their Jannissaries corps. Their attacks on ships off the coast of Africa or in the Mediterranean, and subsequent capture of able-bodied men for ransom or sale provided some captives for the Sultan's system. Starting in the 17th century, Christian families living under the Ottoman rule began to submit their sons into the Kapikulu system willingly, as they saw this as a potentially invaluable career opportunity for their children. Eventually the Sultan turned to foreign volunteers from the warrior clans of Circassians in southern Russia to fill his Janissary armies. As a whole the system began to break down, the loyalty of the Jannissaries became increasingly suspect. Mahmud II forcibly disbanded the Janissary corps in 1826.[14][15]

Similar to the Janissaries in origin and means of development were the Mamluks of Egypt in the Middle Ages. The Mamluks were usually captive non-Muslim Iranian and Turkish children who had been kidnapped or bought as slaves from the Barbary coasts. The Egyptians assimilated and trained the boys and young men to become Islamic soldiers who served the Muslim caliphs and the Ayyubid sultans during the Middle Ages. The first mamluks served the Abbasid caliphs in 9th century Baghdad. Over time they became a powerful military caste. On more than one occasion, they seized power, for example, ruling Egypt from 1250–1517.

From 1250 Egypt had been ruled by the Bahri dynasty of Kipchak origin. Slaves from the Caucasus served in the army and formed an elite corp of troops. They eventually revolted in Egypt to form the Burgi dynasty. The Mamluks' excellent fighting abilities, massed Islamic armies, and overwhelming numbers succeeded in overcoming the Christian Crusader fortresses in the Holy Land. The Mamluks were the most successful defense against the Mongol Ilkhanate of Persia and Iraq from entering Egypt.[16]

On the western coast of Africa, Berber Muslims captured non-Muslims to put to work as laborers. They generally converted the younger people to Islam and many became quite assimilated. In Morocco, the Berber looked south rather than north. The Moroccan Sultan Moulay Ismail, called "the Bloodthirsty" (1672–1727), employed a corps of 150,000 black slaves, called his Black Guard. He used them to coerce the country into submission.[17]

In modern times

Modern conscription, the massed military enlistment of national citizens, was devised during the French Revolution, to enable the Republic to defend itself from the attacks of European monarchies. Deputy Jean-Baptiste Jourdan gave its name to the 5 September 1798 Act, whose first article stated: "Any Frenchman is a soldier and owes himself to the defense of the nation." It enabled the creation of the Grande Armée, what Napoleon Bonaparte called "the nation in arms," which overwhelmed European professional armies that often numbered only into the low tens of thousands. More than 2.6 million men were inducted into the French military in this way between the years 1800 and 1813.[18]

The defeat of the Prussian Army in particular shocked the Prussian establishment, which had believed it was invincible after the victories of Frederick the Great. The Prussians were used to relying on superior organization and tactical factors such as order of battle to focus superior troops against inferior ones. Given approximately equivalent forces, as was generally the case with professional armies, these factors showed considerable importance. However, they became considerably less important when the Prussian armies faced forces that outnumbered their own in some cases by more than ten to one. Scharnhorst advocated adopting the levée en masse, the military conscription used by France. The Krümpersystem was the beginning of short-term compulsory service in Prussia, as opposed to the long-term conscription previously used.[19]

In the Russian Empire, the military service time "owed" by serfs was 25 years at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1834 it was decreased to 20 years. The recruits were to be not younger than 17 and not older than 35.[20] In 1874 Russia introduced universal conscription in the modern pattern, an innovation only made possible by the abolition of serfdom in 1861. New military law decreed that all male Russian subjects, when they reached the age of 20, were eligible to serve in the military for six years.[21]

In the decades prior to World War I universal conscription along broadly Prussian lines became the norm for European armies, and those modeled on them. By 1914 the only substantial armies still completely dependent on voluntary enlistment were those of Britain and the United States. Some colonial powers such as France reserved their conscript armies for home service while maintaining professional units for overseas duties.

World Wars

The range of eligible ages for conscripting was expanded to meet national demand during the World Wars. In the United States, the Selective Service System drafted men for World War I initially in an age range from 21 to 30 but expanded its eligibility in 1918 to an age range of 18 to 45.[22] In the case of a widespread mobilization of forces where service includes homefront defense, ages of conscripts may range much higher, with the oldest conscripts serving in roles requiring lesser mobility. Expanded-age conscription was common during the Second World War: in Britain, it was commonly known as "call-up" and extended to age 51. Nazi Germany termed it Volkssturm ("People's Storm") and included men as young as 16 and as old as 60.[23] During the Second World War, both Britain and the Soviet Union conscripted women. The United States was on the verge of drafting women into the Nurse Corps because it anticipated it would need the extra personnel for its planned invasion of Japan. However, the Japanese surrendered and the idea was abandoned.[24]

Arguments against conscription

Gender-based

Both feminists[25][26][27] and opponents of discrimination against men[28][29]:102 have criticized military conscription, or compulsory military service, as sexist.

Feminists have argued that military conscription is sexist because wars serve the interests of the patriarchy, the military is a sexist institution, conscripts are therefore indoctrinated in sexism, and conscription of men normalizes violence by men as socially acceptable.[30][31] Feminists have been organizers and participants in resistance to conscription in several countries.[32][33][34][35]

Historically, only men have been subjected to conscription,.[29][36][37][38][39] In the second half of the 20th century, women began to be conscripted, primarily in communist/socialist countries. The integration of women into militaries, and especially into combat forces, did not begin on a large scale until the second half of the 20th century. Men who opt out of military service must often perform alternative service, such as Zivildienst in Austria and Switzerland, whereas women do not have even these obligations.

Involuntary servitude

American libertarians oppose conscription and call for the abolition of the Selective Service System, believing that impressment of individuals into the armed forces is "involuntary servitude."[40] Ron Paul, a former presidential nominee of the U.S. Libertarian Party has said that conscription "is wrongly associated with patriotism, when it really represents slavery and involuntary servitude."[41] The philosopher Ayn Rand opposed conscription, suggesting that "of all the statist violations of individual rights in a mixed economy, the military draft is the worst. It is an abrogation of rights. It negates man's fundamental right—the right to life—and establishes the fundamental principle of statism: that a man's life belongs to the state, and the state may claim it by compelling him to sacrifice it in battle."[42]

In 1917, a number of radicals and anarchists, including Emma Goldman, challenged the new draft law in federal court arguing that it was a direct violation of the Thirteenth Amendment's prohibition against slavery and involuntary servitude. However, the Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the draft act in the case of Arver v. United States on 7 January 1918. The decision said the Constitution gave Congress the power to declare war and to raise and support armies. The Court emphasized the principle of the reciprocal rights and duties of citizens:

- "It may not be doubted that the very conception of a just government in its duty to the citizen includes the reciprocal obligation of the citizen to render military service in case of need and the right to compel.".[43]

Economic

It can be argued that in a cost-to-benefit ratio, conscription during peace time is not worthwhile.[44] Months or years of service amongst the most fit and capable subtracts from the productivity of the economy; add to this the cost of training them, and in some countries paying them. Compared to these extensive costs, some would argue there is very little benefit; if there ever was a war then conscription and basic training could be completed quickly, and in any case there is little threat of a war in most countries with conscription. In the United States, every male resident is required by law to register with the Selective Service System within 30 days following his 18th birthday and is available for a draft (though this is often done automatically via the DMV with licensing or with voter registration).

The cost of conscription can be related to the parable of the broken window in anti-draft arguments. The cost of the work, military service, does not disappear even if no salary is paid. The work effort of the conscripts is effectively wasted, as an unwilling workforce is extremely inefficient. The impact is especially severe in wartime, when civilian professionals are forced to fight as amateur soldiers. Not only is the work effort of the conscripts wasted and productivity lost, but professionally skilled conscripts are also difficult to replace in the civilian workforce. Every soldier conscripted in the army is taken away from his civilian work, and away from contributing to the economy which funds the military. This may be less a problem in an agrarian or pre-industrialized state where the level of education is generally low, and where a worker is easily replaced by another. However, this is potentially more costly in a post-industrial society where educational levels are high and where the workforce is sophisticated and a replacement for a conscripted specialist is difficult to find. Even direr economic consequences result if the professional conscripted as an amateur soldier is killed or maimed for life; his work effort and productivity is lost.[45]

Arguments in favor of conscription

Political and moral motives

Jean Jacques Rousseau argued vehemently against professional armies, feeling it was the right and privilege of every citizen to participate to the defense of the whole society and a mark of moral decline to leave this business to professionals. He based this view on the development of the Roman republic, which came to an end at the same time as the Roman army changed from a conscript to professional force.[46] Similarly, Aristotle linked the division of armed service among the populace intimately with the political order of the state.[47] Niccolò Machiavelli argued strongly for conscription, seeing the professional armies as the cause of the failure of societal unity in Italy.

Other proponents, such as William James, consider both mandatory military and national service as ways of instilling maturity in young adults.[48] Some proponents, such as Jonathan Alter and Mickey Kaus, support a draft in order to reinforce social equality, create social consciousness, break down class divisions and for young adults to immerse themselves in public enterprise.[49][50][51] Charles Rangel called for the reinstatement of the draft during the Iraq conflict.

Economic and resource efficiency

It is estimated by the British military that in a professional military, a company deployed for active duty in peacekeeping corresponds to three inactive companies at home. Salaries for each are paid from the military budget. In contrast, volunteers from a trained reserve are in their civilian jobs when they are not deployed.[52]

Drafting of women

.jpg)

Traditionally conscription has been limited to the male population of a given body. Women and handicapped males have been exempt from conscription. Many societies have considered, continue to consider military service as a test of manhood and a rite of passage from boyhood into manhood.[53][54]

As of 2013, countries that were actively drafting women into military service included Bolivia,[55] Chad,[56] Eritrea,[57][58][59] Israel,[57][58][60] Mozambique [61] and North Korea.[62] Israel has universal female conscription, although in practice women can avoid service by claiming a religious exemption and over a third of Israeli women do so.[57][58][63] Sudanese law allows for conscription of women, but this is not implemented in practice.[64] In the United Kingdom during World War II, beginning in 1941, women were brought into the scope of conscription but, as all women with dependent children were exempt and many women were informally left in occupations such as nursing or teaching, the number conscripted was relatively few.[65]

In 2015 Norway introduced female conscription, making it the first NATO member and first European country to have a legally compulsory national service for both men and women.[66] In practice only motivated volunteers are selected to join the army in Norway.[67]

In the USSR, there was no systematic conscription of women for the armed forces, but the severe disruption of normal life and the high proportion of civilians affected by World War II after the German invasion attracted many volunteers for what was termed "The Great Patriotic War".[68] Medical doctors of both sexes could and would be conscripted (as officers). Also, the free Soviet university education system required Department of Chemistry students of both sexes to complete an ROTC course in NBC defense, and such female reservist officers could be conscripted in times of war. The United States came close to drafting women into the Nurse Corps in preparation for a planned invasion of Japan.[69][70]

In 1981 in the United States, several men filed lawsuit in the case Rostker v. Goldberg, alleging that the Selective Service Act of 1948 violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by requiring that only men register with the Selective Service System (SSS). The Supreme Court eventually upheld the Act, stating that "the argument for registering women was based on considerations of equity, but Congress was entitled, in the exercise of its constitutional powers, to focus on the question of military need, rather than 'equity.'"[71]

On October 1, 1999 in the Taiwan Area, the Judicial Yuan of the Republic of China in its Interpretation 490 considered that the physical differences between males and females and the derived role differentiation in their respective social functions and lives would not make drafting only males a violation of the Constitution of the Republic of China.[72] Though women are not conscripted in Taiwan, transsexual persons are exempt.[73]

Conscientious objection

A conscientious objector is an individual whose personal beliefs are incompatible with military service, or, more often, with any role in the armed forces."[74][75] In some countries, conscientious objectors have special legal status, which augments their conscription duties. For example, Sweden used to allow conscientious objectors to choose a service in the "weapons-free" branch, such as an airport fireman, nurse or telecommunications technician.

The reasons for refusing to serve are varied. Some conscientious objectors are so for religious reasons — notably, the members of the historic peace churches, pacifist by doctrine; Jehovah's Witnesses, while not strictly pacifists, refuse to participate in the armed forces on the ground that they believe Christians should be neutral in worldly conflicts.

By country

| Country | Conscription[76] | Land area (km2)[77][78] | GDP nominal (US$M)[78][79] | Per capita GDP (US$)[78][80] |

Population[81][82][83] | Government[84][85] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (abolished in 2010)[86] | 27,398 | $12,380 | $3,745.86 | 3,010,000 | Republic | |

| Yes | 2,381,740 | $227,802 | $5,886[87] | 38,090,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes | 1,246,700 | $113,700 | $4,389.45 | 18,570,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No. Voluntary; conscription may be ordered for specified reasons; per Public Law No.24.429 promulgated on 5 January 1995 | 2,736,690 | $468,800 | $8,662.99[88] | 42,610,000 | Presidential Federal Republic | |

| No (abolished by parliament in 1972)[89] | 7,617,930 | $1,520,000 | $55,290.43 | 22,260,000 | Parliamentary Federal Monarchy | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[90] | 82,444 | $417,900 | $43,660.31 | 8,220,000 | Parliamentary Federal Republic | |

| No | 10,070 | $8,040 | $20,909.96 | 319,031 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No | 133,910 | $121,300 | $662.36 | 163,650,000 | Republic | |

| No | 431 | $4,170 | $14,133.58 | 288,725 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No (Conscription was abolished as of 1 January 1994 under the so-called Delcroix Bill of 6 July 1993) | 30,278 | $477,400 | $42,338.25 | 10,440,000 | Parliamentary Federal Monarchy | |

| No. Military service is voluntary. | 22,806 | $1,560 | $4,637.15 | 334,297 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No[91] | 47,000 | $2,140 | $1,948.56 | 725,296 | Monarchy | |

| Yes (when annual number of volunteers falls short of goal)[92] | 1,084,390 | $26,860 | $1,888.43 | 10,460,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (abolished on January 1, 2006)[93] | 51,197 | $17,090 | $4,243.45 | 3,880,000 | Federal Republic | |

| Yes, but almost all of the recruits have been volunteers in recent years.[94] (alternative service is foreseen in law,[95] but it is not advertised to the public and seems not to be implemented[94]) | 8,456,510 | $2,220,000 | $10,368.31 | 201,010,000 | Presidential Federal Republic | |

| No (abolished by law on January 1, 2008)[96] | 110,550 | $50,330 | $5,951.46 | 6,980,000 | Republic | |

| No | 9,093,507 | $1,800,000 | $45,829.42 | 34,570,000 | Parliamentary Federal Monarchy | |

| Yes | 748,800 | $264,500 | $11,614.65 | 17,220,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (Citizens 18 years of age are required to register in PLA offices, but policy not enforced. Policy exempted in Hong Kong and Macao)[97] | 9,326,410 | $15,722,500 | $11,150.67 | 1,410,000,000 | Communist state | |

| Yes | 1,141,748 | $427,139 | $8,858.54 | 48,747,632 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (abolished by law in 2008)[98] | 56,414 | $55,710 | $13,563.31 | 4,480,000 | Republic | |

| Yes | 110,860 | $72,300 | $5,095.83 | 11,060,000 | Communist State | |

| Yes | 9,240 | $22,690 | $20,612.77 | 1,160,000 | Presidential Republic[99] | |

| No (abolished in 2005)[100] | 77,276 | $193,000 | $18,555.50 | 10,160,000 | Republic | |

| Yes, however a great majority of the recruits have been volunteers over the past few years[101] (alternative service available)[102][103] | 42,394 | $310,600 | $56,221.67 | 5,560,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No | 22,980 | $1,340 | $1,365.65 | 792,198 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes | 276,840 | $82,900 | $3,766.40 | 15,440,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes | 995,450 | $253,300 | $2,776.79 | 85,290,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No. Legal, not practiced. | 20,720 | $23,540 | $3,505.84 | 6,110,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | 45,339 | $22,100 | $14,028.17 | 1,270,000 | Republic | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | 304,473 | $244,300 | $44,375.23 | 5,270,000 | Republic | |

| No (suspended for peacetime in 2001)[104] | 640,053[105] | $2,580,000 | $39,288.81 | 65,950,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No | 10,000 | $896 | $618.81 | 1,880,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (suspended for peacetime by federal legislature effective from 1 July 2011)[106] | 349,223 | $3,380,000 | $40,427.05 | 81,150,000 | Federal Republic | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | 130,800 | $245,800 | $26,707.93 | 10,770,000 | Republic | |

| No (no military service) | 344 | $779 | $6,161.81 | 109,590 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No (Peacetime conscription abolished in 2004)[107] | 92,340 | $124,000 | $13,229.97 | 9,940,000 | Republic | |

| No | 2,973,190 | $2,400,000 | $1,747.70 | 1,220,000,000 | Federal Republic | |

| No | 1,826,440 | $866,700 | $2,888.11 | 251,160,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No | 70,273 | $250,286 | $53,841.00 | 4,588,252 | Parliamentary Republic | |

| Yes | 1,636,000 | $541,200 | $4,537.87 | 79,850,000 | Islamic Republic | |

| Yes | 20,330 | $254,000 | $26,404.85 | 7,710,900 | Republic | |

| No (suspended for peacetime in 2005)[108] | 294,020 | $1,990,000 | $33,678.67 | 61,480,000 | Republic | |

| No | 10,831 | $14,640 | $4,586.63 | 2,910,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No. Japanese Constitution abolished conscription. Enlistment in Japan Self-Defense Force is voluntary at 18 years of age.[109] | 377,944 | $4,580,000 | $42,298.79 | 127,250,000 | Parliamentary Democracy, Constitutional Monarchy | |

| Yes. The government decided in 2007 to reintroduce conscription, which had been suspended in 1999.[110] | 91,971 | $30,790 | $4,487.26 | 6,480,000 | Monarchy | |

| Yes[111][112] | 120,538[111] | $28,000[111] | $1,800.00[111] | 24,851,627[111] | Single-party Hereditary Juche | |

| Yes, unless medical conditions either exempts or allows civil service instead. Athletes winning medals at the Olympics are exempt. Graduates from special high schools or those with a master's degree in engineering may work at selected workplaces for 3 years instead. | 98,190 | $1,670,000 | $34,961.55 | 48,960,000 | Presidential Democracy, Republic with Unitary form of government | |

| Yes[113] | 17,820 | $182,000 | $39,210.05 | 2,700,000 | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy | |

| No (abolished in 2007)[114] | 10,230 | $40,780 | $9,018.47 | 4,130,000 | Republic | |

| Yes | 1,759,540 | $80,810 | $12,897.70 | 6,000,000 | Transitional government[115] | |

| Yes by law, but all recent recruits have been volunteers.[116] | 65,300[117] | $41,570 | $10,870.69 | 3,520,000 | Republic | |

| No | 2,586 | $56,370 | $103,421.82 | 514,862 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No (abolished in 2006)[118] | 25,713 | $9,500 | $3,646.55 | 2,090,000 | Republic | |

| No,[119] (Malaysian National Service) suspended from Jan 2015 due to government budget cuts [120] | 328,550 | $300,600 | $7,745.13 | 29,630,000 | Federal Monarchy | |

| No | 300 | $2,080 | $4,399.84 | 393,988 | Presidential Republic | |

| No | 316 | $8,630 | $18,752.63 | 411,277 | Republic | |

| Yes | 1,923,040 | $1,160,000 | $8,516.67 | 116,220,000 | Federal Republic | |

| Yes | 33,371 | $7,150 | $1,503.90 | 3,620,000 | Republic | |

| sources differ No (FWCC[126]) | 657,740 | $54,530 | $686.48 | 55,170,000 | Parliamentary Republic | |

| No. Suspended since 1997 (except for Curaçao and Aruba)[127] See also: Conscription in the Netherlands | 33,883 | $760,400 | $46,360.62 | 16,810,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No, conscription abolished in December 1972. | 268,021 | $167,500 | $31,594.85 | 4,370,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| Yes by law, but in practice people are not forced to serve against their will.[67] Also total objectors have not been punished since 2011, instead they are simply exempted from the service.[128] | 307,442 | $492,900 | $84,573.26 | 4,720,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No | 778,720 | $222,500 | $1,009.53 | 193,240,000 | Federal Republic | |

| No[126][129][130] | 298,170 | $246,800 | $2,019.38 | 105,720,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (ended in 2009),[132] although there is an obligatory military qualification to valuate abilities in case of war | 304,459 | $483,200 | $12,308.92 | 38,380,000 | Republic | |

| No (Peacetime conscription abolished in 2004 but there remains a symbolic military obligation to all 18-year-old people, from both sexes. It is called National Defense Day, (Dia da Defesa Nacional in Portuguese)).[133] | 91,951 | $209,600 | $21,029.96 | 10,800,000 | Republic | |

| No | 11,437 | $189,800 | $100,297.57 | 2,040,000 | Monarchy | |

| No (ended in 2007)[134] | 230,340 | $167,100 | $7,388.75 | 21,790,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes (alternative service available) | 16,995,800 | $2,274,000 | $16,372.99 | 142,500,000 | Presidential Federal Republic | |

| No | 24,948 | $7,010 | $25.34 | 12,020,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No | 2,149,690 | $701,400 | $15,936.38 | 26,940,000 | Monarchy | |

| Yes | 455 | $1,020 | $10,237.27 | 90,846 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes | 719.1 | $308,051 | $56,319.00 | 5,535,000 | Republic | |

| No[135] | 20,151 | $44,810 | $22,669.33 | 1,990,000 | Republic | |

| No (ended in 1994, formalized in 2002)[136] | 1,219,912 | $379,100 | $7,089.23 | 48,600,000 | Republic | |

| No (abolished by law on December 31, 2001)[137] | 499,542 | $1,310,000 | $29,845.26 | 47,370,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No | 17,203 | $3,700 | $2,652.65 | 1,400,000 | Monarchy | |

| No (suspended in 2010). Since 2014 former conscrips and volunteers may now be called to refresher training [138][139] | 410,934 | $516,700 | $47,408.19 | 9,120,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| Yes (Alternative service available)[140] | 39,770 | $522,400 | $66,408.19 | 7,639,961 | Federal Republic | |

| Yes | 184,050 | $64,700 | $2,769.28 | 22,460,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes (alternative service available)[141] An all-volunteer force is planned by the end of 2014, but conscription will remain in practice thereafter.[142] | 32,260 | $484,700[143] | $20,749.21[143] | 23,359,928[143] | Presidential Republic | |

| Yes | 511,770 | $361,000 | $4,707.67 | 67,450,000 | Military Junta endorsed by Monarchy | |

| No | 718 | $465 | $2,891.51 | 106,322 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No | 5,128 | $25,400 | $15,962.71 | 1,227,505 | Republic | |

| Yes (Paid military exemption has also been introduced five times since 1980 for various reasons with the last one announced in December 2014.) | 770,760 | $777,600 | $19,556.00 | 80,690,000 | Republic | |

| Yes (Implemented recently, compulsory for young male citizens. Residents not required to apply) [144] | 83,600 | $269,800 | $29,900 | 5,628,805 | Constitutional monarchy | |

| Yes[3] | 603,700 | $173,900 | $2,977.94 | 44,570,000 | Presidential Republic | |

| No (abolished December 31, 1960, except Bermuda Regiment)[145] | 241,590 | $2,440,000 | $36,276.82 | 63,180,000 | Parliamentary Monarchy | |

| No[146] – draft abandoned in 1973 under President Nixon. However, in 1980, President Carter reinstated a requirement that men register with the U.S. Selective Service System within 30 days of their 18th birthday. | 9,161,923 | $16,820,000 | $51,264.02 | 302,670,000 | Presidential Democracy, Federal Republic | |

| No | 12,200 | $776 | $3,051.22 | 261,565 | Republic | |

| Yes[147][148] | 882,050 | $376,100 | $9,084.09 | 28,460,000 | Presidential Federal Republic |

China

Universal conscription in China dates back to the State of Qin, which eventually became the Qin Empire of 221 BC. Following unification, historical records show that a total of 300,000 conscript soldiers and 500,000 conscript labourers constructed the Great Wall of China.[149]

In the following dynasties, universal conscription was abolished and reintroduced on numerous occasions.

As of 2011, universal military conscription is theoretically mandatory in the People's Republic of China, and reinforced by law. However, due to the large population of China and large pool of candidates available for recruitment, the People's Liberation Army has always had sufficient volunteers, so conscription has not been required in practice at all.

Europe

Denmark

Conscription is known in Denmark since the Viking Age, where one man out of every 10 had to serve the king. Frederick IV of Denmark changed the law in 1710 to every 4th man. The men were chosen by the landowner and it was seen as a penalty.

Since 12 February 1849, every physically fit man must do military service. According to §81 in the Constitution of Denmark, which was promulgated in 1849:

Every male person able to carry arms shall be liable with his person to contribute to the defence of his country under such rules as are laid down by Statute. — Constitution of Denmark[150]

The legislation about compulsory military service is articulated in the Danish Law of Conscription.[151] National service takes 4–12 months.[152] It is possible to postpone the duty when one is still in full-time education.[153] Every male turning 18 will be drafted to the 'Day of Defence', where they will be introduced to the Danish military and their health will be tested.[154] Physically unfit persons are not required to do military service.[152][155] It is only compulsory for men, while women are free to choose to join the Danish army.[156] Almost all of the men have been volunteers in recent years,[157] 96.9% of the total amount of recruits having been volunteers in the 2015 draft.[158]

After some sort of lottery,[159] one can become a conscientious objector.[160] Total objection (refusal from alternative civilian service) results in up to 4 months jailtime.[161]

Netherlands

Conscription, which was called "Service Duty" (Dutch: dienstplicht) in the Netherlands, was first employed in 1810 by French occupying forces. Napoleon's brother Louis Bonaparte, who was King of Holland from 1806 to 1810, had tried to introduce conscription a few years earlier, unsuccessfully. Every man aged 20 years or older had to enlist. By means of drawing lots it was decided who had to undertake service in the French army. It was possible to arrange a substitute against payment.

Later on, conscription was used for all men over the age of 18. Postponement was possible, due to study, for example. Conscientious objectors could perform an alternative civilian service instead of military service. For various reasons, this forced military service was criticized at the end of the twentieth century. Since the Cold War was over, so was the direct threat of a war. Instead, the Dutch army was employed in more and more peacekeeping operations. The complexity and danger of these missions made the use of conscripts controversial. Furthermore, the conscription system was thought to be unfair as only men were drafted.

In the European part of Netherlands, compulsory attendance has been officially suspended since 1 May 1997. Between 1991 and 1996, the Dutch armed forces phased out their conscript personnel and converted to an all-volunteer force. The last conscript troops were inducted in 1995, and demobilized in 1996. The suspension means that citizens are no longer forced to serve in the armed forces, as long as it is not required for the safety of the country. Since then, the Dutch army is an all-volunteer force. However, to this day, every male and female[162] citizen aged 17 gets a letter in which he is told that he has been registered but does not have to present himself for service. The Dutch army allowed its male soldiers to have long hair from the early 1970s to the end of conscription in the mid-1990s.

Even though it is generally thought that conscription has been abolished in the Netherlands, it is compulsory attendance that was abolished, not conscription. The laws and systems which provide for the conscription of armed forces personnel still remain in place.

Norway

As of March 2016, Norway currently employs a weak form of mandatory military service for men and women. In practice recruits are not forced to serve, instead only those who are motivated are selected.[163] About 60,000 Norwegians are available for conscription every year, but only 8,000 to 10,000 are conscripted.[164] On 14 June 2013 the Norwegian Parliament voted to extend conscription to women, making Norway the first NATO member and first European country to make national service compulsory for both sexes.[165] There is a right of conscientious objection. In earlier times, up until at least the early 2000s, all men aged 19–44 were subject to mandatory service, with good reasons required to avoid becoming drafted. Since 1985, women have been able to enlist for voluntary service as regular recruits.

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom introduced conscription to full-time military service for the first time in January 1916 (the eighteenth month of World War I) and abolished it in 1920. Ireland, then part of the United Kingdom, was excepted from the original 1916 military service legislation, and although further legislation in 1918 gave power for an extension of conscription to Ireland, the power was never put into effect.

Conscription was reintroduced in 1939, in the lead up to World War II, and continued in force until 1963. Northern Ireland was excepted from conscription legislation throughout the whole period.

In all, 8,000,000 men were conscripted in the Second World War, as well as several hundred thousand younger single women.[166] The introduction of conscription in May 1939, before the war began, was partly due to pressure from the French, who emphasized the need for a large British army to oppose the Germans.[167] From early 1942 unmarried women age 19–30 were conscripted. Most were sent to the factories, but they could volunteer for the Auxiliary Territorial Service (ATS) and other women's services. None was assigned to combat roles unless she volunteered. By 1943 women were liable to some form of directed labour up to age 51. During the Second World War, 1.4 million British men volunteered for service and 3.2 million were conscripted. Conscripts comprised 50% of the Royal Air Force, 60% of the Royal Navy and 80% of the British Army.[168]

The abolition of conscription in Britain was announced on 4 April 1957, by new prime minister Harold Macmillan, with the last conscripts being recruited three years later.[169]

Israel

In Israel, the Muslim and Christian Arab minority are exempt from mandatory service, as are permanent residents such as the Druze of the Golan Heights. Male Ultra-Orthodox Jews may apply for a deferment of draft to study in Yeshiva, and the deferment tends to become an exemption, while female religious Jews can be exempted after presenting "religious declaration" to the IDF authorities, and some (primarily National Religious or Modern Orthodox) choose to volunteer for national service instead. Male Druze and Circassian Israeli citizens are liable, by agreement with their community leaders (Female Druze and Circassian are exempt from service). Members of the exempted groups can still volunteer, including Bedouin males, who serve in relatively large numbers.

United States

In the United States, conscription, also called "the draft", ended in 1973, but males aged 18 are required to register with the Selective Service System to enable a reintroduction of conscription if necessary between 18 and 27. President Gerald Ford suspended mandatory draft registration in 1975, but President Jimmy Carter reinstated that requirement when the Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan. Selective Service registration is still required of almost all young men, although the draft has not been used since 1973[170] and there have been no prosecutions for violations of the draft registration law since 1986.[171]

Colonial and early national

In America before 1862, combat duty was always voluntary, but citizens aged 18 to 45 were usually compelled to join local militia units. Colonial militia laws—and after 1776 those of the states—required able-bodied white men to enroll in the militia and to undergo a minimum of military training, all without pay. Colonial Pennsylvania (controlled by Quakers) did not have such laws. Members of pacifist religious denominations were exempt. When combat troops were needed, some of the militiamen volunteered for short terms of service, for which they were paid. Following this system in its essentials, the Continental Congress in 1778 recommended that the states draft men from their militias for one year's service in the Continental army; this first national conscription was irregularly applied and failed to fill the Continental ranks.

In 1814, President James Madison proposed conscription of 40,000 men for the army, but the War of 1812 ended before Congress took any action. An 1840 proposal for a standing army of 200,000 men included conscription, but it never passed and military service was voluntary before 1862.[172]

American Civil War

Although both North and South resorted to conscription during the Civil War, in neither region did the system work effectively. The Confederate Congress on April 16, 1862, passed an act requiring military service for three years from all males aged eighteen to thirty-five not legally exempt, and it later extended the obligation so that all soldiers were required to serve for the duration of the conflict. The U.S. Congress followed on July 17, 1862, with an act authorizing a militia draft within a state when it could not meet its quota with volunteers. However, this failed to produce adequate enlistees, and with few men still volunteering by late 1862, it became necessary for the first time to impose national conscription. This met with considerable outcry among states rights advocates who wrote numerous letters to President Lincoln pleading against the unconstitutionality of such an action. In the end however, their complaints were ignored as Congress approved the first national conscription act on March 1, 1863, which made all white males between 20 and 44 liable for military service.

Quotas were assigned in each state, the deficiencies in volunteers to be met by conscription. But men drafted could provide substitutes or, until mid-1864, avoid service by paying commutation money. Many eligibles pooled their money to cover the cost of anyone drafted. Families used the substitute provision to select which man should go into the army and which should stay home. There was much evasion and overt resistance to the draft, especially in Catholic areas. The great draft riot in New York City in July 1863 involved Irish immigrants who had been signed up as citizens to swell the machine vote, not realizing it made them liable for the draft. Of the 168,649 men procured for the Union through the draft, 117,986 were substitutes, leaving only 50,663 who had their personal services conscripted.

In the end, conscription was largely a failure. The draft failed to bring in high-quality soldiers to the Union armies and instead most draftees were lazy, unmotivated men, men with physical or mental disabilities, and even criminals. They frequently met with contempt from the volunteer soldiers and required extra amounts of discipline and surveillance to prevent them from committing desertion and petty crimes.

The problem of Confederate desertion was aggravated by the inequitable inclinations of conscription officers and local judges. The three conscription acts of the Confederacy exempted certain categories, most notably the planter class, and enrolling officers and local judges often practiced favoritism, sometimes accepting bribes. Attempts to effectively deal with the issue were frustrated by conflict between state and local governments on the one hand and the national government of the Confederacy.[173]

World War I

In 1917, the administration of Woodrow Wilson decided to rely primarily on conscription, rather than voluntary enlistment, to raise military manpower for World War I. The Selective Service Act of 1917 was carefully drawn to remedy the defects in the Civil War system and—by allowing exemptions for dependency, essential occupations, and religious scruples—to place each man in his proper niche in a national war effort. The act established a "liability for military service of all male citizens"; authorized a selective draft of all those between twenty-one and thirty-one years of age (later from eighteen to forty-five); and prohibited all forms of bounties, substitutions, or purchase of exemptions. Administration was entrusted to local boards composed of leading civilians in each community. These boards issued draft calls in order of numbers drawn in a national lottery and determined exemptions. In 1917 and 1918 some 24 million men were registered and nearly 3 million inducted into the military services, with little of the resistance that characterized the Civil War.[174]

World War II

In 1940 Congress passed the first peacetime draft legislation, which was led by Grenville Clark. It was renewed (by one vote) in summer 1941. It involved questions as to who should control the draft, the size of the army, and the need for deferments. The system worked through local draft boards comprising community leaders who were given quotas and then decided how to fill them. There was very little draft resistance.[175]

The nation went from a surplus manpower pool with high unemployment and relief in 1940 to a severe manpower shortage by 1943. Industry realized that the Army urgently desired production of essential war materials and foodstuffs more than soldiers. (Large numbers of soldiers were not used until the invasion of Europe in summer 1944.) In 1940 to 1943, the Army often transferred soldiers to civilian status in the Enlisted Reserve Corps in order to increase production. Those transferred would return to work in essential industry, although they could be called back to active duty if the Army needed them. Others were discharged if their civilian work was deemed absolutely essential. There were instances of mass releases of men to increase production in various industries. Blacks and Asians were drafted under the same terms as whites. Over ten million men were drafted for combat in World War II, more than twice the amount drafted for World War One, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War combined.

One contentious issue involved the drafting of fathers, which was avoided as much as possible. Farmers demanded and were generally given occupational deferments (many volunteered anyway, and those who stayed at home were not eligible for postwar veteran's benefits). The draft law as established in 1940 exempted males under 21 from mandatory service due to public opposition against the idea of drafting 18-year-olds.

Later in the war, as the need for manpower grew more and more pressing, many earlier deferment categories became draft eligible.[176]

Draft evasion

The New York Draft Riots (July 11 to July 16, 1863; known at the time as Draft Week), were violent disturbances in New York City that were the culmination of discontent with new laws passed by Congress to draft men to fight in the ongoing American Civil War.

In the United States and some other countries, the Vietnam War saw new levels of opposition to conscription and the Selective Service System. Many people opposed to and facing conscription chose to either apply for classification and assignment to civilian alternative service or noncombatant service within the military as conscientious objectors, or to evade the draft by fleeing to a neutral country. A small proportion, like Muhammad Ali, chose to resist the draft by publicly and politically fighting conscription. Some people resisted at the point of registration for the draft. In the United States around 1970, for example, the draft resistance movement focused on mandatory draft registration. Others resisted at the point of induction, when they were ordered to put on a uniform, when they were ordered to carry or use a weapon, or when they were ordered into combat.

In the United States, especially during the Vietnam War, some used political connections to ensure that they were placed well away from any potential harm, serving in what was termed a Champagne unit. Many would avoid military service altogether through college deferments, by becoming fathers, or serving in various exempt jobs (teaching was one possibility). Others used educational exemptions, became conscientious objectors or pretended to be conscientious objectors, although they might then be drafted for non-combat work, such as serving as a combat medic. It was also possible they could be asked to do similar civilian work, such as being a hospital orderly.

It was, in fact, quite easy for those with some knowledge of the system to avoid being drafted. A simple route, widely publicized, was to get a medical rejection. While a person could claim to have symptoms (or feign homosexuality) if enough physicians sent letters that a person had a problem, he might well be rejected. It often wasn't worth the Army's time to dispute this claim. Such an approach worked best in a larger city where there was no stigma to not serving, and the potential draftee was not known to those reviewing him.

For others, the most common method of avoiding the draft was to cross the border into another country. People who have been "called up" for military service and who attempted to avoid it in some way were known as "draft-dodgers". Particularly during the Vietnam War, U.S. draft-dodgers usually made their way to Canada, Mexico, or Sweden.

Many people looked upon draft-dodgers with scorn as being "cowards", but some supported them in their efforts. In the late years of the Vietnam War, objections against it and support for draft-dodgers was much more outspoken, because of the casualties suffered by American troops, and the actual cause and purpose of the war being heavily questioned.

Toward the end of the U.S. draft, an attempt was made to make the system somewhat fairer by turning it into a lottery, with each of the year's calendar dates randomly assigned a number. Men born on lower-numbered dates were called up for review. For the reasons given above, this did not make the system any fairer, and the entire system ended in 1973. By 1975, the draft was no longer mandatory. Today, American men aged 18–25 are required to register with the Selective Service, but there has not been a call-up since the Vietnam War and nobody has been prosecuted for violating the draft registration law since 1986.[171]

Main articles for conscription by country

- Conscription in Canada

- Conscription in Egypt

- Conscription in Finland

- Conscription in France

- Conscription in Germany

- Conscription in Gibraltar

- Conscription in Greece

- Conscription in Malaysia

- Conscription in Mexico

- Conscription in New Zealand

- Conscription in Russia

- Conscription in Serbia

- Conscription in Singapore

- Conscription in South Korea

- Conscription in Switzerland

- Conscription in the Netherlands

- Conscription in the Ottoman Empire

- Conscription in the Republic of China (Taiwan)

- Conscription in the Russian Empire

Related concepts

- Arrière-ban

- Civil conscription

- Civilian Public Service

- Corvée

- Economic conscription

- Impressment and the Quota System

- National Service

- Zivildienst

- Pospolite ruszenie, mass mobilization in Poland

See also

- Bevin Boys

- Ephebic Oath

- List of countries by number of troops

- Men's Rights

- Military history

- Military recruitment

- Timeline of women's participation in warfare

References

- ↑ "Conscription". Merriam-Webster Online.

- ↑ "Ukraine to end military conscription after autumn call-ups".

- 1 2 "BBC News – Ukraine reinstates conscription as crisis deepens". BBC News.

- ↑ "Georgia Promises To End Military Conscription – Again".

- ↑ "Taiwan prepares for end of conscription".

- ↑ "Turkey: How Conscription Reform Will Change the Military".

- ↑ "Seeking Sanctuary: Draft Dodgers". CBC Digital Archives.

- ↑ "World War II". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 0-415-11032-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Postgate, J.N. (1992). Early Mesopotamia Society and Economy at the Dawn of History. Routledge. p. 243. ISBN 0-415-11032-7.

- ↑ Sturdy, David Alfred the Great Constable (1995), p153

- ↑ Bernard Lewis. "Race and Slavery in the Middle East". Chapter readings for class at Fordham University.

- ↑ "In the Service of the State and Military Class".

- ↑ "Janissary corps, or Janizary, or Yeniçeri (Turkish military)". Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- ↑ Tore Kjeilen. "Janissaries – LookLex Encyclopaedia". i-cias.com.

- ↑ "The Mamluk (Slave) Dynasty (Timeline)". Sunnah Online.

- ↑ Lewis (1994). "Race and Slavery in the Middle East". Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Conscription. Archived from the original on 2009-10-31.

- ↑ Dierk Walter. Preussische Heeresreformen 1807–1870: Militärische Innovation und der Mythos der "Roonschen Reform". 2003, in Citino, p. 130

- ↑ "Military service in Russia Empire". roots-saknes.lv.

- ↑ "Conscription and Resistance: The Historical Context archived from the original". 2008-06-03. Archived from the original on 2008-06-03.

- ↑ "Records of the Selective Service System (World War I)".; see also Selective Service Act of 1917 and Selective Training and Service Act of 1940.

- ↑ "The German Volkssturm from Intelligence Bulletin". lonesentry.com. February 1945.

- ↑ "CBC News Indepth: International military". CBC News. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013.

- ↑ Stephen, Lynn (1981). "Making the Draft a Women's Issue". Women: A Journal of Liberation. 8 (1). Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Lindsey, Karen (1982). "Women and the Draft". In McAllister, Pam. Reweaving the Web of Life: Feminism and Nonviolence. New Society Publishers. ISBN 0865710163.

- ↑ Levertov, Denise (1982). "A Speech: For Antidraft Rally, D.C. March 22, 1980". Candles in Babylon. New Directions Press. ISBN 9780811208314.

- ↑ Berlatsky, Noah (May 29, 2013). "When Men Experience Sexism". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- 1 2 Benatar, David (May 15, 2012). The Second Sexism: Discrimination Against Men and Boys. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-67451-2. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ Michalowski, Helen (May 1982). "Five feminist principles and the draft". Resistance News (8): 2.

- ↑ Neudel, Marian Henriquez (July 1983). "Feminism and the Draft". Resistance News (13): 7.

- ↑ "Letters from draft-age women about why they wouldn't register for the draft". Resistance News (2): 6. 1 March 1980.

- ↑ "Gestation: Women and Draft Resistance". Resistance News (11). November 1982.

- ↑ "Women and the resistance movement". Resistance News (21). 8 June 1986.

- ↑ "No to Equality in Militarism! (Statement of the feminist collective TO MOV co-signed by the Association of Greek Conscientious Objectors)". Countering the Militarisation of Youth. War Resisters International. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ Goldstein, Joshua S. (2003). "War and Gender: Men's War Roles – Boyhood and Coming of Age". In Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures. Volume 1. Springer. p. 108. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Kronsell, Anica (June 29, 2006). "Methods for studying silence: The 'silence' of Swedish conscription". In Ackerly, Brooke A.; Stern, Maria; True, Jacqui Feminist Methodologies for International Relations. Cambridge University Press. p. 113. ISBN 978-1-139-45873-3. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Selmeski, Brian R. (2007). Multicultural Citizens, Monocultural Men: Indigineity, Masculinity, and Conscription in Ecuador. Syracuse University: ProQuest. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-549-40315-9. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Joenniemi, Pertti (2006). The Changing Face of European Conscription. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 142–149. ISBN 978-0-754-64410-1. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ "CONSCRIPTION AND THE MILITARY". Libertarian Party. dehnbase.org. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ U.S. Representative Ron Paul Conscription Is Slavery, antiwar.com, January 14, 2003.

- ↑ "Draft". aynrandlexicon.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ John Whiteclay Chambers II, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987) p 219-20

- ↑ Henderson, David R. "The Role of Economists in Ending the Draft" (August 2005).

- ↑ Milton Friedman (1967). "Why Not a Volunteer Army?". New Individualist Review. Retrieved September 11, 2008.

- ↑ Rousseau, J-J. Social Contract. Chapter "The Roman Comitia"

- ↑ Aristotle, Politics, Book 6 Chapter VII and Book 4 Chapter XIII.

- ↑ William James (1906). "The Moral Equivalent of War".

- ↑ Alter, Jonathan. "Cop Out on Class". Newsweek.

- ↑ "Interview with Mickey Kaus". realclearpolitics.com.

- ↑ Postrel, Virginia. "Overcoming Merit".

- ↑ Gustav Hägglund (2006). Leijona ja kyyhky (in Finnish). Otava. ISBN 951-1-21161-7.

- ↑ Ben Shephard (2003). A War of Nerves: Soldiers and Psychiatrists in the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-674-01119-9.

- ↑ Carol R. Ember; Melvin Ember (2003). Encyclopedia of sex and gender: men and women in the world's cultures. Volume 2. Springer. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-306-47770-6.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Bolivia".

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Chad". Archived from the original on 2013-04-24.

- 1 2 3 "Women in the military — international". CBC News Indepth: International military. May 30, 2006. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "The Economic Costs and the Political Allure of Conscription" (PDF). (see footnote 3)

- ↑ "Cia World Factbook: Eritrea".

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Israel".

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: Mozambique".

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook: North Korea".

- ↑ Abuse of IDF Exemptions Questioned The Jewish Daily Forward, 16 Dec 2009

- ↑ "World Resisters International: Sudan, Country Report".

- ↑ Roger Broad (2006). Conscription in Britain, 1939–1964: the militarisation of a generation. Taylor & Francis. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-7146-5701-1.

^ "Conscription into military service". Peace Pledge Union. - ↑ "Universal Conscription". Norwegian Armed Forces. 11 June 2015. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2016.

- 1 2 (www.dw.com), Deutsche Welle. "Norway's military conscription becomes gender neutral - News - DW.COM - 14.10.2014". dw.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Jack Cassin-Scott; Angus McBride (1980). Women at war, 1939–45. Osprey Publishing. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-85045-349-2.

- ↑ "Draft Women?". Time. January 15, 1945. Retrieved 2008-08-12.

- ↑ Kalisch, PA; Kalisch PA; Kalisch BJ (1973). "The women's draft. An analysis of the controversy over the nurses' Selective Service Bill of 1945". Nursing research. PubMed. 22 (5): 402–13. doi:10.1097/00006199-197309000-00004. PMID 4580476.

- ↑ "Rostker v. Goldberg". Cornell Law School. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ↑ "Judicial Yuan Interpretation 490". translated by Jiunn-rong Yeh.

- ↑ "Attachment of the standard of the class of physical condition of a draftee" (in Chinese). Conscription Agency, Ministry of the Interior.

- ↑ On July 30, 1993, explicit clarification of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights Article 18 was made in the United Nations Human Rights Committee general comment 22, Para. 11: "Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief. Framework for communications. Conscientious Objection". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 2012-05-07.

- ↑ "International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights; See Article 18". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- 1 2 "Nationmaster: Conscription". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, Geneva, Switzerland, 1997. Data collected from the nations concerned, or as otherwise indicated.

- ↑ "Nationmaster: Land area".

- 1 2 3 "CIA World Factbooks". cia.gov. 18 December 2003.

- ↑ "Nationmaster: GDP".

- ↑ "Nationmaster: Per capita GDP".

- ↑ "Nationmaster: Population".

- ↑ "World Development Indicators database". Archived from the original on 15 October 2008.

- ↑ "CIA World Factbook". cia.gov.

- 1 2 "Nationmaster: Government type".

- ↑ "CIA World Factbooks". cia.gov. 18 December 2003.

- ↑ Koci, Jonilda (August 21, 2008). "Albania to abolish conscription by 2010". SETimes. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ "Algeria". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects : Argentina, 2007–2010". imf.org.

- ↑ Gary Brown (October 12, 1999). "Current Issues Brief 7 1999–2000 – Military Conscription: Issues for Australia". Parliamentary library; Foreign Affairs, Defence and Trade Group. Archived from the original on August 19, 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-10.

- ↑ "Official information website".

- ↑ "The World Factbook: Military service age and obligation". CIA.

- ↑ "South America > Bolivia > Military". nationmaster.com.

- ↑ "NATO and the Defence Reform Commission: partners for progress". setimes.com.

- 1 2 Brasil, Portal. "Publicidade sobre isenção no serviço militar é proibida". Portal Brasil (in Portuguese). Retrieved 2016-07-19.

- ↑ LEI No 4.375, DE 17 DE AGOSTO DE 1964. – Military Service Law at government's official website

- ↑ "Country report and updates: Bulgaria22 October 2008". War Resisters' International. 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "Country report and updates: China". War Resisters' International. 15 March 1998.

All male citizens must register at the local PLA office in the year they reach the age of 18. Local governments get annual recruitment quotas, and local PLA offices select recruits according to medical and political criteria and military requirements. Call-up for military service then takes place at the age of 18.

- ↑ "Croatia to abolish conscription military service sooner". Southeast European Times. May 10, 2007. Retrieved 2008-05-30.

- ↑ Note: a separation of the two ethnic communities inhabiting Cyprus began following the outbreak of communal strife in 1963; this separation was further solidified after the Turkish intervention in July 1974 that followed a Greek junta-supported coup attempt gave the Turkish Cypriots de facto control in the north; Greek Cypriots control the only internationally recognized government; on 15 November 1983 Turkish Cypriot "President" Rauf DENKTASH declared independence and the formation of a "Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus" (TRNC), which is recognized only by Turkey[84]

- ↑ "Official site of Ministry of defense and armed forces of the Czech Republic". Ministry of Defense and armed forces of the Czech Republic. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ↑ "Værnepligtige ('Conscripts')". Forsvarsministeriets Personalestyrelse (in Danish). Retrieved 2016-11-23.

- ↑ "Værnepligtsloven (Law on conscription)" (in Danish).

- ↑ "Lov om værnepligtens opfyldelse ved civilt arbejde (Law on fulfilling conscription duties by civilian work)" (in Danish).

- ↑ "Country report and updates: France". War Resisters' International. October 23, 2008.

- ↑ Includes the overseas regions of French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Martinique, and Reunion."France". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2008-04-09.

- ↑ "WPflG – Einzelnorm". gesetze-im-internet.de.

- ↑ "Country report and updates: Hungary". War Resisters' International. October 23, 2008.

- ↑ warresisters (23 October 2008). "Italy". wri-irg.org. War Resisters International.

- ↑ ChartsBin. "Military Conscription Policy by Country". chartsbin.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Child Soldiers Global Report 2008 indicates, citing "Mustafa al-Riyalat Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Korea, North". CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ "North Korea, Military Conscription and Terms of Service". Based on the Country Studies Series by Federal Research Division of the Library of Congress. Retrieved 2007-08-12.

- ↑ Toumi, Habib. "Kuwait lawmakers approve military conscription". Gulf News. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ↑ "Lebanon". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2008-05-30

- ↑ CIA Factbook: Libya.

- ↑ "Baltic Times – Lithuania welcomes first 495 volunteers to its army".

- ↑ "CIA Factbook: Lithuania".

- ↑ "Macedonia: Conscription abolished". War Resisters' International. 1 June 2006

- ↑ "BBC NEWS - Asia-Pacific - Malaysian youth face call-up". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Budget Revision: National Service 2015 suspended - Nation - The Star Online". thestar.com.my. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Burma to bring in conscription". January 11, 2011. Retrieved January 13, 2011.

- ↑ "Burma: World's Highest Number of Child Soldiers". Human rights Watch. October 15, 2002.

- ↑ "Six Youths Conscripted into Burmese Army". Narinjara News. August 4, 2009. Archived from the original on June 14, 2010.

- ↑ "Arakanese Youth Arrested and Conscripted by Burmese Army". War Resisters' International. June 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Six Youths Conscripted into Burmese Army". Narinjara. August 4, 2009. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011.

- 1 2 Nationmaster : Conscription, citing Friends World Committee for Consultation (FWCC)[76]

- ↑ Conscription still exists, but compulsory attendance was held in abeyance per January 1, 1997 (effective per August 22, 1996), (unknown) (October 12, 1999). "Afschaffing dienstplicht". Tweede Kamer (Dutch House of Representatives) and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal Dutch Library). Archived from the original on 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2009-07-27.

- ↑ "War resisters' international – Norway: end of substitute service for conscientious objectors".

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency. "The World Factbook: Military Service Age and Obligation". Retrieved 28 February 2016.

17-23 years of age (officers 20-24) for voluntary military service; no conscription; applicants must be single male or female Philippine citizens with either 72 college credit hours (enlisted) or a baccalaureate degree (officers) (2013)

- ↑ Section 4 Article II of the Philippine constitution reads, "The prime duty of the Government is to serve and protect the people. The Government may call upon the people to defend the State and, in the fulfillment thereof, all citizens may be required, under conditions provided by law, to render personal, military or civil service." Section 4 Article XVI of the Philippine constitution reads, "The Armed Forces of the Philippines shall be composed of a citizen armed force which shall undergo military training and serve as may be provided by law. It shall keep a regular force necessary for the security of the State."[131]

- ↑ "1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines". Chan Robles Law Library.

- ↑ "Poland's defence minister, Bogdan Klich, said the country will move towards a professional army and that from January, only volunteers will join the armed forces.", Matthew Day (5 August 2008). "Poland ends army conscription". London: telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2009-02-11

- ↑ Instituto Português da Juventude. "Portal da Juventude – Dia da Defesa Nacional – Época 2011 – 2012". juventude.gov.pt.

- ↑ "Background Note: Romania". Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, US Department of State. April 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-30

- ↑ "Changing the Way Slovenia Sees the Armed Forces". slonews. November 18, 2003. Retrieved 2009-10-13

- ↑ "End Conscription Campaign (ECC)". South African History Online. Retrieved 2011-03-13

- ↑ "Conscription ends in Spain after 230 years". April 18, 2014.

- ↑ "Sweden scraps military conscription". washingtontimes.com. 2010-07-01. Retrieved 2012-06-01.

The new policy means that required military service will be applied only if the neutral Nordic nation of 9 million feels threatened.

- ↑ Försvarsmakten. "Försvarsmakten får kalla in till repövningar". forsvarsmakten.se. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ The situation of conscientious objectors in Switzerland – compared with the guidelines of the European Union, zentralstelle-kdv.de Archived February 7, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Substitute Service Center". Department Of Compulsory Military Service, Taipei City Government. Archived from the original on March 24, 2007. Retrieved July 25, 2008

- ↑ Jimmy Chuang (March 10, 2009). "Professional military by 2014: MND". Taipei Times

- 1 2 3 "Taiwan". CIA World Factbook. Retrieved 2007-12-09.

- ↑ Salama, Samir (7 June 2014). "Mandatory national service in UAE approved". GulfNews.com.

- ↑ COMMITTEE PUBLISHES REPORT ON OVERSEAS TERRITORIES (item 26), 4 July 2008

- ↑ The United States abandoned the draft in 1973 under President Richard Nixon, ended the Selective Service registration requirement in 1975 under President Gerald Ford. In 1980, Congress reinstated mandatory registering with the U.S. Selective Service System.* Selective Service System. WHO MUST REGISTER Archived May 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Accessed 20 January 2012.

- ↑ "CONSTITUTION OF THE BOLIVARIAN R E P U B L I C OF VENEZUELA (Promulgation date)" (PDF). analitica.com. December 20, 1999. Articles 134, 135. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-21. Retrieved 2009-11-01.

- ↑ Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (18 December 2003). "Venezuela: Military service, including length of service, existence of alternative forms of service and penalties imposed on those who refuse to serve". U.N. Refugee Agency. Retrieved 2009-11-01

- ↑ Great Wall Archived July 18, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Danish Constitution" (PDF). Parliament.

- ↑ "Bekendtgørelse af værnepligtsloven". Retsinformation. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- 1 2 "Værnepligt". Borger. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Forsvaret". www2.forsvaret.dk. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Mødet på Forsvarets Dag". Forsvaret. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Før Forsvarets Dag". Forsvaret. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Kvinder i Forsvaret". Forsvaret for Danmark. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "19 unge tvunget i militæret". dr.dk. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Værnepligtige". Forsvarsministeriets Personalestyrelse (in Danish). Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ↑ "Mødet på Forsvarets Dag". Forsvaret for Danmark. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Militærnægter". Borger. Retrieved 2016-02-18.

- ↑ "Bekendtgørelse af værnepligtsloven". Retsinformation.de (in Danish). Retrieved 2016-11-22.

- ↑ Defensie, Ministerie van. "Kaderwet dienstplicht wordt aangepast voor vrouwen". rijksoverheid.nl. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ "Norway's military conscription becomes gender neutral". Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 2015-11-24.

- ↑ "NDF official numbers". NDF. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

- ↑ "Norway becomes first NATO country to draft women into military". Reuters. Retrieved 2013-06-15.

- ↑ Roger Broad, Conscription in Britain 1939–1964: The Militarization of a Generation (2006)

- ↑ Daniel Hucker, "Franco-British Relations and the Question of Conscription in Britain, 1938–1939," Contemporary European History, Nov 2008, Vol. 17 Issue 4, pp 437–456

- ↑ Jeremy A. Crang, "'Come into the Army, Maud': Women, Military Conscription, and the Markham Inquiry," Defence Studies, Nov 2008, Vol. 8 Issue 3, pp. 381–395; statistics from pp. 392–3

- ↑ "Those were the days". expressandstar.com. Retrieved 15 October 2016.

- ↑ Gill, Linda. "Military Conscription, Recruiting and the Draft". About.com US Politics. Missing or empty

|title=(help); - 1 2 Hasbrouck, Edward. "Prosecutions of Draft Registration Resisters". Resisters.info. National Resistance Committee. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ↑ United States. War Dept; Joel Roberts Poinsett (1840). Plan of the standing army of 200,000 men: submitted to Congress by the Secretary of War, and recommended by the President of the United States. s.n. pp. 8.

- ↑

- Albert Burton Moore. Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy 1924 online edition

- ↑ John Whiteclay Chambers II, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987)

- ↑ Flynn (1993)

- ↑ George Q. Flynn, The Draft, 1940–1973 (1993)

Further reading

- Burk, James (April 1989). "Debating the Draft in America," Armed Forces and Society p. vol. 15: pp. 431–448.

- Challener, Richard D. The French theory of the nation in arms, 1866–1939 (1955)

- Chambers, John Whiteclay. To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987)

- Fitzpatrick, Edward (1940). Conscription and America: A Study of Conscription in a Democracy. Richard Publishing Company. ASIN B000GY5QW2.

- Flynn, George Q. (1998 33(1): 5–20). "Conscription and Equity in Western Democracies, 1940–75," Journal of Contemporary History in JSTOR

- Flynn, George Q. (2001). Conscription and Democracy: The Draft in France, Great Britain, and the United States. Greenwood. p. 303. ISBN 0-313-31912-X.

- Jehn, Christopher (2008). "Conscription". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Kestnbaum, Meyer (October 2000). Citizenship and Compulsory Military Service: The Revolutionary Origins of Conscription in the United States. Armed Forces & Society. p. vol. 27: pp. 7–36.

- Levi, Margaret (1997). Consent, Dissent and Patriotism. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-59961-0. Looks at citizens' responses to military conscription in several democracies since the French Revolution.

- Linch, Kevin (2012). Conscription. Mainz: Institute of European History (IEG).

- Krueger, Christine, and Sonja Levsen, eds. War Volunteering in Modern Times: From the French Revolution to the Second World War (Palgrave Macmillan 2011)

- Leander, Anna (July 2004). Drafting Community: Understanding the Fate of Conscription. Armed Forces & Society. p. vol. 30: pp. 571–599.

- MacLean, Alair. The Privileges of Rank: The Peacetime Draft and Later-life Attainment. date= July 2008. p. vol. 34: pp. 682–713.

- Mjoset, Lars and Stephen Van Holde, eds. (2002). The Comparative Study of Conscription in the Armed Forces. Amsterdam: JAI Press/Elsevier Science Ltd. p. 424.

- Pfaffenzeller, Stephan. 2010. "Conscription and Democracy: The Mythology of Civil-Military Relations." Armed Forces & Society April Vol. 36 pp. 481–504, doi:10.1177/0095327X09351226 http://afs.sagepub.com/content/36/3/481.abstract

- Sorensen, Henning (January 2000). Conscription in Scandinavia During the Last Quarter Century: Developments and Arguments. Armed Forces & Society. p. vol. 26: pp. 313–334.

- Stevenson, Michael D. (2001). Canada's Greatest Wartime Muddle: National Selective Service and the Mobilization of Human Resources during World War II. McGill-Queen's University Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-7735-2263-8.

External links

The dictionary definition of conscription at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of conscription at Wiktionary Media related to Conscription at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Conscription at Wikimedia Commons