Ulcerative colitis

| Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|

|

Endoscopic image of a colon affected by ulcerative colitis. The internal surface of the colon is blotchy and broken in places. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | gastroenterology |

| ICD-10 | K51 |

| ICD-9-CM | 556 |

| OMIM | 191390 |

| DiseasesDB | 13495 |

| MedlinePlus | 000250 |

| eMedicine | med/2336 |

| Patient UK | Ulcerative colitis |

| MeSH | D003093 |

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a long-term condition that results in inflammation and ulcers of the colon and rectum.[1][2] The primary symptom of active disease is abdominal pain and diarrhea mixed with blood. Weight loss, fever, and anemia may also occur. Often symptoms come on slowly and can range from mild to severe. Symptoms typically occur intermittently with periods of no symptoms between flares.[1] Complications may include megacolon, inflammation of the eye, joints, or liver, and colon cancer.[1][3]

The cause of UC is unknown.[1] Theories involve immune system dysfunction, genetics, changes in the normal gut bacteria, and environmental factors.[1][4] Rates tend to be higher in the developed world with some proposing this to be the result of less exposure to intestinal infections, or a Western diet and lifestyle.[2][5] The removal of the appendix at an early age may be protective.[5] Diagnosis is typically by colonoscopy with tissue biopsies. It is a kind of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) along with Crohn's disease and microscopic colitis.[1]

Dietary changes may improve symptoms. A number of medications are used to treat symptoms and bring about and maintain remission. These include aminosalicylates such as sulfasalazine, steroids, immunosuppressants such as azathioprine, and biological therapy. Removal of the colon by surgery may be necessary if the disease is severe, does not respond to treatment, or if complications such as colon cancer develop.[1] Removal of the colon and rectum can cure the disease.[1][5]

The first description of ulcerative colitis occurred around the 1850s.[5] Each year it newly occurs in 1 to 20 people per 100,000 and 5 to 500 per 100,000 individuals are affected.[2][5] The disease is more common in North America and Europe.[5] Often it begins between 15 and 30 years of age or among those over 60.[1] Males and females appear to be affected equally.[2] It has also become more common since the 1950s.[2][5] Together, ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease affect approximately 500,000 to 2 million people in the United States.[6] With appropriate treatment the risk of death appears the same as that of the general population.[3]

Signs and symptoms

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Defecation | Often porridge-like,[7] sometimes steatorrhea | Often mucus-like and with blood[7] |

| Tenesmus | Less common[7] | More common[7] |

| Fever | Common[7] | Indicates severe disease[7] |

| Fistulae | Common[8] | Seldom |

| Weight loss | Often | More seldom |

Gastrointestinal

The clinical presentation[9] of ulcerative colitis depends on the extent of the disease process. Patients usually present with diarrhea mixed with blood and mucus, of gradual onset that persists for an extended period (weeks). They may also have weight loss and blood on rectal examination. The inflammation caused by the disease along with the chronic blood from the GI tract leads to increased rates of anemia. The disease may be accompanied by different degrees of abdominal pain, from mild discomfort to painful bowel movements or painful abdominal cramping with bowel movements.

Ulcerative colitis is associated with a general inflammatory process that affects many parts of the body. Sometimes these associated extra-intestinal symptoms are the initial signs of the disease, such as painful arthritic knees in a teenager and may be seen in adults also. The presence of the disease may not be confirmed immediately, however, until the onset of intestinal manifestations.

Extent of involvement

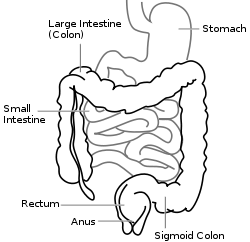

Ulcerative colitis is normally continuous from the rectum up the colon. The disease is classified by the extent of involvement, depending on how far up the colon the disease extends:

- Distal colitis, potentially treatable with enemas:[10]

- Proctitis: Involvement limited to the rectum.

- Proctosigmoiditis: Involvement of the rectosigmoid colon, the portion of the colon adjacent to the rectum.

- Left-sided colitis: Involvement of the descending colon, which runs along the patient's left side, up to the splenic flexure and the beginning of the transverse colon.

- Extensive colitis, inflammation extending beyond the reach of enemas:

- Pancolitis: Involvement of the entire colon, extending from the rectum to the cecum, beyond which the small intestine begins.

Severity of disease

In addition to the extent of involvement, people may also be characterized by the severity of their disease.[10]

- Mild disease correlates with fewer than four stools daily, with or without blood, no systemic signs of toxicity, and a normal erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) or C-reactive protein (CRP). There may be mild abdominal pain or cramping. Patients may believe they are constipated when in fact they are experiencing tenesmus, which is a constant feeling of the need to empty the bowel accompanied by involuntary straining efforts, pain, and cramping with little or no fecal output. Rectal pain is uncommon.

- Moderate disease correlates with more than four stools daily, but with minimal signs of toxicity. Patients may display anemia (not requiring transfusions), moderate abdominal pain, and low grade fever, 38 to 39 °C (100 to 102 °F).

- Severe disease, correlates with more than six bloody stools a day or observable massive and significant bloody bowel movement, and evidence of toxicity as demonstrated by fever, tachycardia, anemia or an elevated ESR or CRP.

- Fulminant disease correlates with more than ten bowel movements daily, continuous bleeding, toxicity, abdominal tenderness and distension, blood transfusion requirement and colonic dilation (expansion). Patients in this category may have inflammation extending beyond just the mucosal layer, causing impaired colonic motility and leading to toxic megacolon. If the serous membrane is involved, a colonic perforation may ensue. Unless treated, the fulminant disease will soon lead to death.

Extraintestinal features

As ulcerative colitis is believed to have a systemic (i.e., autoimmune) origin, patients may present with comorbidities leading to symptoms and complications outside the colon. The frequency of such extraintestinal manifestations has been reported as anywhere between 6 and 47 percent.[11] These include the following:

- Aphthous ulcer of the mouth

- Ophthalmic

- Iritis or uveitis, which is inflammation of the eye's iris

- Episcleritis

- Musculoskeletal:

- Seronegative arthritis, which can be a large-joint oligoarthritis (affecting one or two joints), or may affect many small joints of the hands and feet

- Ankylosing spondylitis, arthritis of the spine

- Sacroiliitis, arthritis of the lower spine

- Cutaneous (related to the skin):

- Erythema nodosum, which is a panniculitis, or inflammation of subcutaneous tissue involving the lower extremities

- Pyoderma gangrenosum, which is a painful ulcerating lesion involving the skin

- Deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism

- Autoimmune hemolytic anemia

- Clubbing, a deformity of the ends of the fingers.

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis, a distinct disease that causes inflammation of the bile ducts

Causes

There are no direct known causes for ulcerative colitis, but there are many possible factors such as genetics and stress.

Genetic factors

A genetic component to the etiology of ulcerative colitis can be hypothesized based on the following:[12]

- Aggregation of ulcerative colitis in families.

- Identical twin concordance rate of 10% and dizygotic twin concordance rate of 3%[13]

- Ethnic differences in incidence

- Genetic markers and linkages

There are 12 regions of the genome that may be linked to ulcerative colitis, including, in the order of their discovery, chromosomes 16, 12, 6, 14, 5, 19, 1, and 3,[14] but none of these loci have been consistently shown to be at fault, suggesting that the disorder arises from the combination of multiple genes. For example, chromosome band 1p36 is one such region thought to be linked to inflammatory bowel disease.[15]

Some of the putative regions encode transporter proteins such as OCTN1 and OCTN2. Other potential regions involve cell scaffolding proteins such as the MAGUK family. There may even be human leukocyte antigen associations at work. In fact, this linkage on chromosome 6 may be the most convincing and consistent of the genetic candidates.[14]

Multiple autoimmune disorders have been recorded with the neurovisceral and cutaneous genetic porphyrias including ulcerative colitis, Crohn's disease, celiac disease, dermatitis herpetiformis, diabetes, systemic and discoid lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, scleroderma, Sjogren's disease and scleritis. Physicians should be on high alert for porphyrias in families with autoimmune disorders and care must be taken with potential porphyrinogenic drugs, including sulfasalazine.

Environmental factors

Many hypotheses have been raised for environmental contributants to the pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis. They include the following:

- Diet: as the colon is exposed to many dietary substances which may encourage inflammation, dietary factors have been hypothesized to play a role in the pathogenesis of both ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. There have been few studies to investigate such an association, one study showed no association of refined sugar on the prevalence of ulcerative colitis.[16] High intake of unsaturated fat and vitamin B6 may enhance the risk of developing ulcerative colitis.[17] Other identified dietary factors that may influence the development and/or relapse of the disease include meat protein and alcoholic beverages.[18][19] Specifically, sulfur has been investigated as being involved in the etiology of ulcerative colitis, but this is controversial.[20] Sulfur restricted diets have been investigated in patients with UC and animal models of the disease. The theory of sulfur as an etiological factor is related to the gut microbiota and mucosal sulfide detoxification in addition to the diet.[21][22][23]

- Breastfeeding: There have been conflicting reports of the protection of breastfeeding in the development of inflammatory bowel disease. One Italian study showed a potential protective effect.[24]

- One study of isotretinoin found a small increased in the rate of ulcerative colitis.[25]

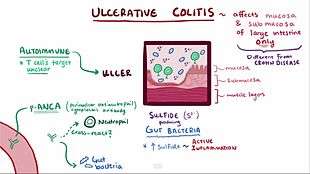

Autoimmune disease

Ulcerative colitis is an autoimmune disease characterized by T-cells infiltrating the colon.[26] In contrast to Crohn's disease, which can affect areas of the gastrointestinal tract outside of the colon, ulcerative colitis usually involves the rectum and is confined to the colon, with occasional involvement of the ileum. This so-called "backwash ileitis" can occur in 10–20% of patients with pancolitis and is believed to be of little clinical significance.[27] Ulcerative colitis can also be associated with comorbidities that produce symptoms in many areas of the body outside the digestive system. Surgical removal of the large intestine often cures the disease.[10]

Alternative theories

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Higher risk for smokers | Lower risk for smokers[28] |

| Age | Usual onset between 15 and 30 years[29] | Peak incidence between 15 and 25 years |

Levels of sulfate-reducing bacteria tend to be higher in persons with ulcerative colitis. This could mean that there are higher levels of hydrogen sulfide in the intestine. An alternative theory suggests that the symptoms of the disease may be caused by toxic effects of the hydrogen sulfide on the cells lining the intestine.[30]

Pathophysiology

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Cytokine response | Associated with Th17[31] | Vaguely associated with Th2 |

An increased amount of colonic sulfate-reducing bacteria has been observed in some patients with ulcerative colitis, resulting in higher concentrations of the toxic gas hydrogen sulfide. Human colonic mucosa is maintained by the colonic epithelial barrier and immune cells in the lamina propria (see intestinal mucosal barrier). N-butyrate, a short-chain fatty acid, gets oxidized through the beta oxidation pathway into carbon dioxide and ketone bodies. It has been shown that N-butyrate helps supply nutrients to this epithelial barrier. Studies have proposed that hydrogen sulfide plays a role in impairing this beta-oxidation pathway by interrupting the short chain acetyl-CoA dehydrogenase, an enzyme within the pathway. Furthermore, it has been suggested that the protective benefit of smoking in ulcerative colitis is due to the hydrogen cyanide from cigarette smoke reacting with hydrogen sulfide to produce the non-toxic isothiocyanate, thereby inhibiting sulfides from interrupting the pathway.[32] An unrelated study suggested that the sulfur contained in red meats and alcohol may lead to an increased risk of relapse for patients in remission.[30]

Ulcerative colitis patients typically present with rectal bleeding, diarrhea, tenesmus (urgent desire to evacuate the bowels but with the passage of little stool), and lower abdominal pain. The severity of disease at clinical presentation is important in determining the appropriate therapy. Patients with mildly active disease will have fewer than 4 bowel movements daily and no signs of toxicity. Individuals with moderate-severity UC have more frequent bowel movements with bleeding. Approximately 70% of patients with ulcerative colitis will have moderately active disease at presentation. Patients with severely active disease will have signs of toxicity with fever, tachycardia, and anemia. Patients with fulminant or toxic colitis or toxic megacolon often have more than 10 bowel movements in a day, continuous bleeding, abdominal distention and tenderness, and radiologic evidence of edema and, in some cases, bowel dilation. These people most often require immediate colectomy because 10% have perforated colon at the time of surgery.

Diagnosis

_active.jpg)

The initial diagnostic workup for ulcerative colitis includes the following:[10][33]

- A complete blood count is done to check for anemia; thrombocytosis, a high platelet count, is occasionally seen

- Electrolyte studies and renal function tests are done, as chronic diarrhea may be associated with hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia and pre-renal failure.

- Liver function tests are performed to screen for bile duct involvement: primary sclerosing cholangitis.

- X-ray

- Urinalysis

- Stool culture, to rule out parasites and infectious causes.

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate can be measured, with an elevated sedimentation rate indicating that an inflammatory process is present.

- C-reactive protein can be measured, with an elevated level being another indication of inflammation.

- sigmoidoscopy a type of endoscopy which can detect the presence of ulcers in the large intestine after a trial of an enema.

Although ulcerative colitis is a disease of unknown causation, inquiry should be made as to unusual factors believed to trigger the disease.[10] Factors may include: recent cessation of tobacco smoking; recent administration of large doses of iron or vitamin B6; hydrogen peroxide in enemas or other procedures.

The simple clinical colitis activity index was created in 1998 and is used to assess the severity of symptoms.[34][35]

Endoscopic

_endoscopic_biopsy.jpg)

The best test for diagnosis of ulcerative colitis remains endoscopy. Full colonoscopy to the cecum and entry into the terminal ileum is attempted only if the diagnosis of UC is unclear. Otherwise, a flexible sigmoidoscopy is sufficient to support the diagnosis. The physician may elect to limit the extent of the exam if severe colitis is encountered to minimize the risk of perforation of the colon. Endoscopic findings in ulcerative colitis include the following:

- Loss of the vascular appearance of the colon

- Erythema (or redness of the mucosa) and friability of the mucosa

- Superficial ulceration, which may be confluent, and

- Pseudopolyps.

Ulcerative colitis is usually continuous from the rectum, with the rectum almost universally being involved. There is rarely perianal disease, but cases have been reported. The degree of involvement endoscopically ranges from proctitis or inflammation of the rectum, to left sided colitis, to pancolitis, which is inflammation involving the ascending colon.

Histologic

Biopsies of the mucosa are taken to definitively diagnose UC and differentiate it from Crohn's disease, which is managed differently clinically. Microbiological samples are typically taken at the time of endoscopy. The pathology in ulcerative colitis typically involves distortion of crypt architecture, inflammation of crypts (cryptitis), frank crypt abscesses, and hemorrhage or inflammatory cells in the lamina propria. In cases where the clinical picture is unclear, the histomorphologic analysis often plays a pivotal role in determining the diagnosis and thus the management. By contrast, a biopsy analysis may be indeterminate, and thus the clinical progression of the disease must inform its treatment.

Differential diagnosis

The following conditions may present in a similar manner as ulcerative colitis, and should be excluded:

- Crohn's disease

- Infectious colitis, which is typically detected on stool cultures

- Pseudomembranous colitis, or Clostridium difficile-associated colitis, bacterial upsets often seen following administration of antibiotics

- Ischemic colitis, inadequate blood supply to the intestine, which typically affects the elderly

- Radiation colitis in patients with previous pelvic radiotherapy

- Chemical colitis resulting from the introduction of harsh chemicals into the colon from an enema or other procedure.

The most common disease that mimics the symptoms of ulcerative colitis is Crohn's disease, as both are inflammatory bowel diseases that can affect the colon with similar symptoms. It is important to differentiate these diseases since the course of the diseases and treatments may be different. In some cases, however, it may not be possible to tell the difference, in which case the disease is classified as indeterminate colitis.

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Terminal ileum involvement | Commonly | Seldom |

| Colon involvement | Usually | Always |

| Rectum involvement | Seldom | Usually[28] |

| Involvement around the anus | Common[8] | Seldom |

| Bile duct involvement | No increase in rate of primary sclerosing cholangitis | Higher rate[36] |

| Distribution of disease | Patchy areas of inflammation (skip lesions) | Continuous area of inflammation[28] |

| Endoscopy | Deep geographic and serpiginous (snake-like) ulcers | Continuous ulcer |

| Depth of inflammation | May be transmural, deep into tissues[8][14] | Shallow, mucosal |

| Stenosis | Common | Seldom |

| Granulomas on biopsy | May have non-necrotizing non-peri-intestinal crypt granulomas[8][37][38] | Non-peri-intestinal crypt granulomas not seen[28] |

Management

Standard treatment for ulcerative colitis depends on the extent of involvement and disease severity. The goal is to induce remission initially with medications, followed by the administration of maintenance medications to prevent a relapse of the disease. The concept of induction of remission and maintenance of remission is very important. The medications used to induce and maintain a remission somewhat overlap, but the treatments are different. Physicians first direct treatment to inducing a remission which involves relief of symptoms and mucosal healing of the lining of the colon and then longer term treatment to maintain the remission and prevent complications. Acute severe ulcerative colitis requires hospitalisation, exclusion of infections, and corticosteroids.[39]

Medication

Ulcerative colitis can be treated with a number of medications, including 5-ASA drugs such as sulfasalazine and mesalazine. Corticosteroids such as prednisone can also be used due to their immunosuppressing and short-term healing properties, but because their risks outweigh their benefits, they are not used long-term in treatment. Immunosuppressive medications such as azathioprine and biological agents such as infliximab and adalimumab are given only if people cannot achieve remission with 5-ASA and corticosteroids. This is because of their possible risk factors, including but not limited to increased risk of cancers in teenagers and adults,[40] tuberculosis, and new or worsening heart failure (these side effects are rare). A formulation of budesonide was approved by the FDA for treatment of active ulcerative colitis in January 2013.[41] The evidence on methotrexate does not show a benefit in producing remission in people with ulcerative colitis.[42] Off-label use of drugs such as ciclosporin and tacrolimus has shown some benefits.[43][44] Fexofenadine, an antihistamine drug used in treatment of allergies, has shown promise in a combination therapy in some studies.[45][46] Opportunely, low gastrointestinal absorption (or high absorbed drug gastrointestinal secretion) of fexofenadine results in higher concentration at the site of inflammation. Thus, the drug may locally decrease histamine secretion by involved gastrointestinal mast cells and alleviate the inflammation.

Aminosalicylates

Sulfasalazine has been a major agent in the therapy of mild to moderate ulcerative colitis for over 50 years. In 1977, Mastan S. Kalsi et al. determined that 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA and mesalazine) was the therapeutically active component in sulfasalazine.[47] Since then, many 5-ASA compounds have been developed with the aim of maintaining efficacy but reducing the common side effects associated with the sulfapyridine moiety in sulfasalazine.[48]

Biologics

Biologic treatments such as the TNF inhibitors infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab are commonly used to treat people with UC who are no longer responding to corticosteroids. Tofacitinib, vedolizumab, and etrolizumab can also produce good clinical remission and response rates in UC.[4] Usually, these medications are only used if other options have been exhausted (i.e., the person has received and not responded favorably to high-dose corticosteroids and immunomodulators such as azathioprine and mesalazine).

Unlike aminosalicylates, biologics can cause serious side effects such as an increased risk of developing extra-intestinal cancers,[40] heart failure; and weakening of the immune system, resulting in a decreased ability of the immune system to clear infections and reactivation of latent infections such as tuberculosis. For this reason, patients on these treatments are closely monitored and are often given tests for hepatitis and tuberculosis at least once a year.

Nicotine

Unlike Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis has a lesser prevalence in smokers than non-smokers.[49][50] Studies using a transdermal nicotine patch have shown clinical and histological improvement.[51]

In one double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in the United Kingdom, 48.6% of patients who used the nicotine patch, in conjunction with their standard treatment, showed complete resolution of symptoms. Another randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, single-center clinical trial conducted in the United States showed that 39% of patients who used the patch showed significant improvement, versus 9% of those given a placebo.[52] Use of a transdermal nicotine patch without the addition of other standard treatments such as mesalazine has relapse occurrence rates similar to standard treatment without the use of nicotine.

Iron supplementation

The gradual loss of blood from the gastrointestinal tract, as well as chronic inflammation, often leads to anemia, and professional guidelines suggest routinely monitoring for this with blood tests repeated every three months in active disease and annually in quiescent disease.[53] Adequate disease control usually improves anemia of chronic disease, but iron deficiency anemia should be treated with iron supplements. The form in which treatment is administered depends both on the severity of the anemia and on the guidelines that are followed. Some advise that parenteral iron be used first because patients respond to it more quickly, it is associated with fewer gastrointestinal side effects, and it is not associated with compliance issues.[54] Others require oral iron to be used first, as patients eventually respond and many will tolerate the side effects.[53][55] All guidelines advise that parenteral iron should be administered in cases of severe anemia (a hemoglobin level less than 10).

Treatments in development

Inflammation of the colon is a characteristic symptom of ulcerative colitis, and a new series of drugs in development looks to disrupt the inflammation process by selectively targeting an ion channel. A crucial step involved in the inflammation signaling cascade involves an intermediate conductance calcium activated potassium channel (IK channel) known as KCa3.1;[56] a protein coded for in the human gene KCNN4.[57] Ongoing research seeks to prevent T-cell activation and inflammation by inhibiting the KCa3.1 channel, selectively.[58] Since there is an upregulation of IK channel activity during T cell activation,[56] inhibition of the KCa3.1 is able to disrupt the production of Th1 cytokines IL-2 and TNF-∝. Production of these cytokines decreases because inhibition of KCa3.1 reduces the efflux of K+, which in turn diminishes the influx of Ca2+. By lowering elevated intracellular Ca2+ in patients with ulcerative colitis, these novel drug candidates can inhibit the signaling cascade involved in the inflammation process[58] and help relieve many of the symptoms associated with ulcerative colitis.

Preclinical study results in 2012 indicated that these selective inhibitors decreased colon inflammation in mice and rats cloned with the human KCa3.1 protein as effectively as the standard inflammatory bowel disease treatment of sulfasalazine. However, these novel selective IK channel blockers are significantly more potent and theoretically would be able to be taken at a much more manageable dosage.[58]

Benzothiazinone, NS6180, is a novel class KCa3.1 channel inhibitor in development. Through a number of in vitro experiments, NS6180 was qualified for KCa3.1 channel inhibition. In vivo experiment of DNBS (2,4 - dinitrobenzene sulfonic acid) induced rat colitis, a frequently used animal model for inflammatory bowel disease, showed comparable efficacy and greater potency than sulfasalazine.[58]

Surgery

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | |

|---|---|---|

| Mesalazine | Less useful[59] | More useful[59] |

| Antibiotics | Effective in long-term[60] | Generally not useful[61] |

| Surgery | Often returns following removal of affected part | Usually cured by removal of colon |

Unlike in Crohn's disease, the gastrointestinal aspects of ulcerative colitis can generally be cured by surgical removal of the large intestine, though extraintestinal symptoms may persist. This procedure is necessary in the event of: exsanguinating hemorrhage, frank perforation, or documented or strongly suspected carcinoma. Surgery is also indicated for patients with severe colitis or toxic megacolon. Patients with symptoms that are disabling and do not respond to drugs may wish to consider whether surgery would improve the quality of life.

Ulcerative colitis affects many parts of the body outside the intestinal tract. In rare cases, the extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease may require removal of the colon.[10]

Another surgical option for ulcerative colitis that is affecting most of the large bowel is called the ileo-anal pouch procedure. This is a two- to three-step procedure in which the large bowel is removed, except for the rectal stump and anus, and a temporary ileostomy is made. The next part of the surgery can be done in one or two steps and is usually done at six- to twelve-month intervals from each prior surgery.

In the next step of the surgery, an internal pouch is made of the patient's own small bowel, and this pouch is then hooked back up internally to the rectal stump so that the patient can once again have a reasonably functioning bowel system, all internal. The temporary ileostomy can be reversed at this time so that the patient is internalized for bowel functions, or, in another step to the procedure, the pouch, and rectal stump anastamosis can be left inside the patient to heal for some time while the patient still uses the ileostomy for bowel function. Then, on a subsequent surgery, the ileostomy is reversed and the patient has internalized bowel function again.

Leukocyte apheresis

A type of leukocyte apheresis, known as granulocyte and monocyte adsorptive apheresis, still requires large-scale trials to determine whether or not it is effective.[62] Results from small trials have been tentatively positive.[63]

Bacterial recolonization

- In a number of randomized clinical trials, probiotics have demonstrated the potential to be helpful in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Specific types of probiotics such as Escherichia coli Nissle have been shown to induce remission in some patients for up to a year.[64] Another type of probiotic that is said to have a similar effect is Lactobacillus acidophilus. The probiotics are said to work by calming some of the ongoing inflammation that causes the disease, which in turn allows the body to mobilize dendritic cells, otherwise known as messenger immune cells. These cells then are able to produce other T-cells that further aid in restoring balance in the intestines by rebalancing systematic inflammation.[65]

- Fecal bacteriotherapy involves the infusion of human probiotics through fecal enemas. Ulcerative colitis typically requires a more prolonged bacteriotherapy treatment than Clostridium difficile infection to be successful, possibly due to the time needed to heal the ulcerated epithelium. The response of ulcerative colitis is potentially very favorable with one study reporting 67.7% of sufferers experiencing complete remission.[66] It suggests that the cause of ulcerative colitis may be a previous infection by a still unknown pathogen. This initial infection resolves itself naturally, but somehow causes an imbalance in the colonic bacterial flora, leading to a cycle of inflammation which can be broken by "recolonizing" the colon with bacteria from a healthy bowel. There have been several reported cases of patients who have remained in remission for up to 13 years.[67]

Alternative medicine

About 21% of inflammatory bowel disease patients use alternative treatments.[68] A variety of dietary treatments show promise, but they require further research before they can be recommended.[69]

- Melatonin may be beneficial according to in vitro research, animal studies, and a preliminary human study.[70]

- Dietary fiber, meaning indigestible plant matter, has been recommended for decades in the maintenance of bowel function. Of peculiar note is fiber from brassica, which seems to contain soluble constituents capable of reversing ulcers along the entire human digestive tract before it is cooked.[71]

- Fish oil, and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) derived from fish oil, inhibits leukotriene activity, the latter which may be a key factor of inflammation. As an IBD therapy, there are no conclusive studies in support and no recommended dosage. But dosages of EPA between 180 and 1500 mg/day are recommended for other conditions, most commonly cardiac.[72] Fish oil also contains vitamin D, of which the many people with IBD are deficient.[73]

- Short chain fatty acid (butyrate) enema. The epithelial cells in the colon uses butyrate from the contents of the intestine as an energy source. The amount of butyrate available decreases toward the rectum. Inadequate butyrate levels in the lower intestine have been suggested as a contributing factor for the disease. This might be addressed through butyrate enemas.[74] The results however are not conclusive.

- Herbal medications are used by patients with ulcerative colitis. Compounds that contain sulfhydryl may have an effect in ulcerative colitis (under a similar hypothesis that the sulfa moiety of sulfasalazine may have activity in addition to the active 5-ASA component).[75] One randomized control trial evaluated the over-the-counter medication S-methylmethionine and found a significant decreased rate of relapse when the medication was used in conjunction with oral sulfasalazine.[76]

- Helminthic therapy is the use of intestinal parasitic nematodes to treat ulcerative colitis, and is based on the premises of the hygiene hypothesis. Studies have shown that helminths ameliorate and are more effective than daily corticosteroids at blocking chemically induced colitis in mice,[77][78] and a trial of intentional helminth infection of rhesus monkeys with idiopathic chronic diarrhea (a condition similar to ulcerative colitis in humans) resulted in remission of symptoms in 4 out of 5 of the animals treated.[79] A randomised controlled trial of Trichuris suis ova in humans found the therapy to be safe and effective,[80] and further human trials are ongoing.

- Curcumin (tumeric) therapy, in conjunction with taking the medications mesalamine or sulfasalazine, may be effective and safe for maintaining remission in people with quiescent ulcerative colitis. The effect of curcumin therapy alone on quiescent ulcerative colitis is unknown.[81]

Prognosis

| Crohn's disease | Ulcerative colitis | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient deficiency | Higher risk | ||

| Colon cancer risk | Slight | Considerable | |

| Prevalence of extraintestinal complications[82] | |||

| Iritis/uveitis | Females | 2.2% | 3.2% |

| Males | 1.3% | 0.9% | |

| Primary sclerosing cholangitis | Females | 0.3% | 1% |

| Males | 0.4% | 3% | |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | Females | 0.7% | 0.8% |

| Males | 2.7% | 1.5% | |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | Females | 1.2% | 0.8% |

| Males | 1.3% | 0.7% | |

| Erythema nodosum | Females | 1.9% | 2% |

| Males | 0.6% | 0.7% | |

Progression or remission

Patients with ulcerative colitis usually have an intermittent course, with periods of disease inactivity alternating with "flares" of disease. Patients with proctitis or left-sided colitis usually have a more benign course: only 15% progress proximally with their disease, and up to 20% can have sustained remission in the absence of any therapy. Patients with more extensive disease are less likely to sustain remission, but the rate of remission is independent of the severity of the disease.

Colorectal cancer

There is a significantly increased risk of colorectal cancer in patients with ulcerative colitis after ten years if involvement is beyond the splenic flexure. Those with only proctitis or rectosigmoiditis usually have no increased risk.[10] It is recommended that patients have screening colonoscopies with random biopsies to look for dysplasia after eight years of disease activity, at one to two year intervals.[83]

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Ulcerative colitis has a significant association with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a progressive inflammatory disorder of small and large bile ducts. As many as 5% of patients with ulcerative colitis may progress to develop primary sclerosing cholangitis.[84]

Mortality

Research has not revealed any difference in overall risk of dying in patients with Ulcerative colitis from that of the background population. The cause-of-death distribution may be different from that of the background population.[85] It is thought that the disease primarily affects quality of life, and not lifespan.

Other long-term features

Changes that can be seen in chronic ulcerative colitis include granularity, loss of the vascular pattern of the mucosa, loss of haustra, effacement of the ileocecal valve, mucosal bridging, strictures and pseudopolyps.[86]

Epidemiology

The number of new cases per year of ulcerative colitis in North America is 10–12 per 100,000 per year. It begins most commonly between the ages of 15 and 25. The number of people affected is 1–3 per 1000.[87] Another frequent age of onset is the 6th decade of life.

The geographic distribution of ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease is similar worldwide,[88] with highest incidences in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Scandinavia. Higher incidences are seen in northern locations compared to southern locations in Europe[89] and the United States.[90]

As with Crohn's disease, the prevalence of ulcerative colitis is greater among Ashkenazi Jews and decreases progressively in other persons of Jewish descent, non-Jewish Caucasians, Africans, Hispanics, and Asians.[27] Appendectomy prior to age 20 for appendicitis[91] and current tobacco use[92] are protective against development of ulcerative colitis (although former tobacco use is associated with a higher risk of developing ulcerative colitis.[92])

Research

Helminthic therapy using the whipworm Trichuris suis has been shown in a randomized control trial from Iowa to show benefit in patients with ulcerative colitis.[93] The therapy tests the hygiene hypothesis which argues that the absence of helminths in the colons of patients in the developed world may lead to inflammation. Both helminthic therapy and fecal bacteriotherapy induce a characteristic Th2 white cell response in the diseased areas, which was unexpected given that ulcerative colitis was thought to involve Th2 overproduction.[94]

Alicaforsen is a first generation antisense oligodeoxynucleotide designed to bind specifically to the human ICAM-1 messenger RNA through Watson-Crick base pair interactions in order to subdue expression of ICAM-1.[95] ICAM-1 propagates an inflammatory response promoting the extravasation and activation of leukocytes (white blood cells) into inflamed tissue.[95] Increased expression of ICAM-1 has been observed within the inflamed intestinal mucosa of ulcerative colitis sufferers, where ICAM-1 over production correlated with disease activity.[96] This suggests that ICAM-1 is a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.[97]

Gram positive bacteria present in the lumen could be associated with extending the time of relapse for ulcerative colitis.[98]

Notable cases

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Ulcerative Colitis". NIDDK. September 2014. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ford, AC; Moayyedi, P; Hanauer, SB (5 February 2013). "Ulcerative colitis.". BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 346: f432. PMID 23386404.

- 1 2 Wanderås, Magnus Hofrenning; Moum, Bjørn A; Høivik, Marte Lie; Hovde, Øistein (2016-05-06). "Predictive factors for a severe clinical course in ulcerative colitis: Results from population-based studies". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 7 (2): 235–241. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v7.i2.235. ISSN 2150-5349. PMC 4848246

. PMID 27158539.

. PMID 27158539. - 1 2 Akiho, Hirotada; Yokoyama, Azusa; Abe, Shuichi; Nakazono, Yuichi; Murakami, Masatoshi; Otsuka, Yoshihiro; Fukawa, Kyoko; Esaki, Mitsuru; Niina, Yusuke (2015-11-15). "Promising biological therapies for ulcerative colitis: A review of the literature". World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pathophysiology. 6 (4): 219–227. doi:10.4291/wjgp.v6.i4.219. ISSN 2150-5330. PMC 4644886

. PMID 26600980.

. PMID 26600980. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Danese, S; Fiocchi, C (3 November 2011). "Ulcerative colitis.". The New England journal of medicine. 365 (18): 1713–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1102942. PMID 22047562.

- ↑ Tamparo, Carol (2011). Fifth Edition: Diseases of the Human Body. Philadelphia, PA: F. A. Davis Company. p. 409. ISBN 978-0-8036-2505-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 internetmedicin.se > Inflammatorisk tarmsjukdom, kronisk, IBD By Robert Löfberg. Retrieved Oct 2010 Translate.

- 1 2 3 4 Hanauer SB, Sandborn W (2001-03-01). "Management of Crohn's disease in adults" (PDF). American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (3): 635–43. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03671.x. PMID 11280528. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ Hanauer SB (1996). "Inflammatory bowel disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (13): 841–8. doi:10.1056/NEJM199603283341307. PMID 8596552.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kornbluth A, Sachar DB (2004). "Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 99 (7): 1371–85. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. PMID 15233681.

- ↑ Langan RC, Gotsch PB, Krafczyk MA, Skillinge DD (November 2007). "Ulcerative colitis: diagnosis and treatment" (PDF). American Family Physician. 76 (9): 1323–30. PMID 18019875.

- ↑ Orholm M, Binder V, Sørensen TI, Rasmussen LP, Kyvik KO (2000). "Concordance of inflammatory bowel disease among Danish twins. Results of a nationwide study". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 35 (10): 1075–81. doi:10.1080/003655200451207. PMID 11099061.

- ↑ Tysk C, Lindberg E, Järnerot G, Flodérus-Myrhed B (1988). "Ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease in an unselected population of monozygotic and dizygotic twins. A study of heritability and the influence of smoking". Gut. 29 (7): 990–996. doi:10.1136/gut.29.7.990. PMC 1433769

. PMID 3396969.

. PMID 3396969. - 1 2 3 Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ (May 2007). "Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies.". The Lancet. 369 (9573): 1641–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. PMID 17499606. Retrieved 2009-11-04.

- ↑ Cho JH, Nicolae DL, Ramos R, Fields CT, Rabenau K, Corradino S, Brant SR, Espinosa R, LeBeau M, Hanauer SB, Bodzin J, Bonen DK (2000). "Linkage and linkage disequilibrium in chromosome band 1p36 in American Chaldeans with inflammatory bowel disease" (PDF). Human Molecular Genetics. 9 (9): 1425–32. doi:10.1093/hmg/9.9.1425. PMID 10814724.

- ↑ Järnerot G, Järnmark I, Nilsson K (1983). "Consumption of refined sugar by patients with Crohn's disease, ulcerative colitis, or irritable bowel syndrome". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 18 (8): 999–1002. doi:10.3109/00365528309181832. PMID 6673083.

- ↑ Geerling BJ, Dagnelie PC, Badart-Smook A, Russel MG, Stockbrügger RW, Brummer RJ (April 2000). "Diet as a risk factor for the development of ulcerative colitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 95 (4): 1008–13. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01942.x. PMID 10763951.

- ↑ Jowett SL, Seal CJ, Pearce MS, Phillips E, Gregory W, Barton JR, Welfare MR (October 2004). "Influence of dietary factors on the clinical course of ulcerative colitis: a prospective cohort study". Gut. 53 (10): 1479–84. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.024828. PMC 1774231

. PMID 15361498.

. PMID 15361498. - ↑ Andersen V, Olsen A, Carbonnel F, Tjønneland A, Vogel U (March 2012). "Diet and risk of inflammatory bowel disease". Digestive and Liver Disease. 44 (3): 185–94. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2011.10.001. PMID 22055893.

- ↑ Tilg H, Kaser A (1 October 2004). "Diet and relapsing ulcerative colitis: take off the meat?". Gut. 53 (10): 1399–1401. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.035287. PMC 1774255

. PMID 15361484.

. PMID 15361484. - ↑ Moore J, Babidge W, Millard S, Roediger W (January 1998). "Colonic luminal hydrogen sulfide is not elevated in ulcerative colitis". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 43 (1): 162–5. doi:10.1023/A:1018848709769. PMID 9508519.

- ↑ Jørgensen J, Mortensen PB (August 2001). "Hydrogen sulfide and colonic epithelial metabolism: implications for ulcerative colitis". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 46 (8): 1722–32. doi:10.1023/A:1010661706385. PMID 11508674.

- ↑ Picton R, Eggo MC, Langman MJ, Singh S (February 2007). "Impaired detoxication of hydrogen sulfide in ulcerative colitis?". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 52 (2): 373–8. doi:10.1007/s10620-006-9529-y. PMID 17216575.

- ↑ Corrao G, Tragnone A, Caprilli R, Trallori G, Papi C, Andreoli A, Di Paolo M, Riegler G, Rigo GP, Ferraù O, Mansi C, Ingrosso M, Valpiani D (1998). "Risk of inflammatory bowel disease attributable to smoking, oral contraception and breastfeeding in Italy: a nationwide case-control study. Cooperative Investigators of the Italian Group for the Study of the Colon and the Rectum (GISC)" (PDF). International Journal of Epidemiology. 27 (3): 397–404. doi:10.1093/ije/27.3.397. PMID 9698126.

- ↑ Wolverton, SE; Harper, JC (April 2013). "Important controversies associated with isotretinoin therapy for acne.". American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 14 (2): 71–6. doi:10.1007/s40257-013-0014-z. PMID 23559397.

- ↑ Ko IK, Kim BG, Awadallah A, Mikulan J, Lin P, Letterio JJ, Dennis JE (2010). "Targeting improves MSC treatment of inflammatory bowel disease". Mol. Ther. 18 (7): 1365–72. doi:10.1038/mt.2010.54. PMC 2911249

. PMID 20389289.

. PMID 20389289. - 1 2 Fauci et al. Harrison's Internal Medicine, 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2008. ISBN 978-0-07-159991-7

- 1 2 3 4 Kornbluth A, Sachar DB (July 2004). "Ulcerative colitis practice guidelines in adults (update): American College of Gastroenterology, Practice Parameters Committee" (PDF). American Journal of Gastroenterology. 99 (7): 1371–85. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40036.x. PMID 15233681. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 6, 2008. Retrieved 2009-11-07.

- ↑ Crohn's Disease Overview

- 1 2 Roediger WE, Moore J, Babidge W (1997). "Colonic sulfide in pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis" (PDF). Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 42 (8): 1571–9. doi:10.1023/A:1018851723920. PMID 9286219.

- ↑ Elson CO, Cong Y, Weaver CT, Schoeb TR, McClanahan TK, Fick RB, Kastelein RA (2007). "Monoclonal anti-interleukin 23 reverses active colitis in a T cell-mediated model in mice". Gastroenterology. 132 (7): 2359–70. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.104. PMID 17570211.

- ↑ Levine J, Ellis CJ, Furne JK, Springfield J, Levitt, MD (1998). "Fecal Hydrogen Sulfide Production in Ulcerative Colitis". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 98 (8): 83–87.

- ↑ Ulcerative colitis at eMedicine

- ↑ Walmsley, R S; Ayres, R C S; Pounder, R E; Allan, R N (1998). "A simple clinical colitis activity index". Gut. 43 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1136/gut.43.1.29. ISSN 0017-5749.

- ↑ Mardini, Houssam E.; Grigorian, Alla Y. (2014). "Probiotic Mix VSL#3 Is Effective Adjunctive Therapy for Mild to Moderately Active Ulcerative Colitis". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 20 (9): 1562–1567. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000084. ISSN 1078-0998. PMID 24918321.

- ↑ Broomé U, Bergquist A (February 2006). "Primary sclerosing cholangitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and colon cancer". Seminars in Liver Disease. 26 (1): 31–41. doi:10.1055/s-2006-933561. PMID 16496231.

- ↑ Shepherd NA (August 2002). "Granulomas in the diagnosis of intestinal Crohn's disease: a myth exploded?". Histopathology. 41 (2): 166–8. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01441.x. PMID 12147095.

- ↑ Mahadeva U, Martin JP, Patel NK, Price AB (July 2002). "Granulomatous ulcerative colitis: a re-appraisal of the mucosal granuloma in the distinction of Crohn's disease from ulcerative colitis". Histopathology. 41 (1): 50–5. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01416.x. PMID 12121237.

- ↑ Chen, J (Jul 2016). "Review article: acute severe ulcerative colitis - evidence-based consensus statements.". Alimentary Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 44 (2): 127–44. doi:10.1111/apt.13670. PMID 27226344.

- 1 2 Axelrad, JE; Lichtiger, S; Yajnik, V (28 May 2016). "Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer: The role of inflammation, immunosuppression, and cancer treatment.". World journal of gastroenterology (Review). 22 (20): 4794–801. PMID 27239106.

- ↑ "Uceris Approved for Active Ulcerative Colitis". empr.com. 2013-01-16. Retrieved 2013-01-16.

- ↑ Chande, N; Wang, Y; MacDonald, JK; McDonald, JW (27 August 2014). "Methotrexate for induction of remission in ulcerative colitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8 (8): CD006618. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006618.pub3. PMID 25162749.

- ↑ Krishnamoorthy, R., K. R. Abrams, N. Guthrie, S. Samuel, and T. Thomas. "PWE-237 Ciclosporin in acute severe ulcerative colitis: a meta-analysis". Gut 61, no. Suppl 2 (2012): A394-A394.

- ↑ Ogata Haruhiko; Kato Jun; Hirai Fumihito; Hida Nobuyuki; Matsui Toshiyuki; Matsumoto Takayuki; Koyanagi Katsuyoshi; Hibi Toshifumi (2012). "Double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial of oral tacrolimus (FK506) in the management of hospitalized patients with steroid‐refractory ulcerative colitis". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 18 (5): 803–808. doi:10.1002/ibd.21853. PMID 21887732.

- ↑ Raithel, M; Winterkamp, S; Weidenhiller, M; Müller, S; Hahn, EG (2007). "Combination therapy using fexofenadine, disodium cromoglycate, and a hypoallergenic amino acid-based formula induced remission in a patient with steroid-dependent, chronically active ulcerative colitis". International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 22 (7): 833–839. doi:10.1007/s00384-006-0120-y. PMID 16944185.

- ↑ Dhaneshwar, S; Gautam, H (August 2012). "Exploring novel colon-targeting antihistaminic prodrug for colitis". Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 63 (4): 327–337. PMID 23070081.

- ↑ "Ulcerative Colitis Treatment". Ahealthgroup.com. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ S. Kane (2006). "Asacol - A Review Focusing on Ulcerative Colitis" (PDF).

- ↑ Calkins BM (1989). "A meta-analysis of the role of smoking in inflammatory bowel disease". Digestive Diseases and Sciences. 34 (12): 1841–54. doi:10.1007/BF01536701. PMID 2598752.

- ↑ Lakatos PL, Szamosi T, Lakatos L (2007). "Smoking in inflammatory bowel diseases: good, bad or ugly?". World Journal of Gastroenterology. 13 (46): 6134–9. doi:10.3748/wjg.13.6134. PMC 4171221

. PMID 18069751.

. PMID 18069751. - ↑ Guslandi M (October 1999). "Nicotine treatment for ulcerative colitis". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 48 (4): 481–4. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2125.1999.00039.x. PMC 2014383

. PMID 10583016.

. PMID 10583016. - ↑ Sandborn WJ, Tremaine WJ, Offord KP, Lawson GM, Petersen BT, Batts KP, Croghan IT, Dale LC, Schroeder DR, Hurt RD (March 1997). "Transdermal nicotine for mildly to moderately active ulcerative colitis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Annals of Internal Medicine. 126 (5): 364–71. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00004. PMID 9054280.

- 1 2 Goddard, A. F.; James, M. W.; McIntyre, A. S.; Scott, B. B.; British Society of Gastroenterology (2011). "Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia". Gut. 60 (10): 1309–1316. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.228874. PMID 21561874.

- ↑ Inflamm Bowel Dis 2007;13:1545–1553

- ↑ Mowat C, Cole A, Windsor A, Ahmad T, Arnott I, Driscoll R, Mitton S, Orchard T, Rutter M, Younge L, Lees C, Ho GT, Satsangi J, Bloom S (May 2011). "Guidelines for the management of inflammatory bowel disease in adults". Gut. 60 (5): 571–607. doi:10.1136/gut.2010.224154. PMID 21464096.

- 1 2 Ghanshani S.; Wulff H.; Miller M. J.; Rohm H.; Neben A.; Gutman G. A.; Chandy K. G. (2000). "Up-regulation of the IKCa1 potassium channel during T-cell activation Molecular mechanism and functional consequences". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 275 (47): 37137–37149. doi:10.1074/jbc.m003941200. PMID 10961988.

- ↑ Wei AD, Gutman GA, Aldrich R, et al. (2006). "International Union of Pharmacology. LII. Nomenclature and molecular relationships of calcium-activated potassium channels". Pharmacological Reviews. 57 (4): 463–72. doi:10.1124/pr.57.4.9. PMID 16382103.

- 1 2 3 4 Strøbæk D.; Brown D. T.; Jenkins D. P.; Chen Y. J.; Coleman N.; Ando Y.; Christophersen P. (2013). "NS6180, a new KCa3. 1 channel inhibitor prevents T‐cell activation and inflammation in a rat model of inflammatory bowel disease". British Journal of Pharmacology. 168 (2): 432–444. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.02143.x. PMID 22891655.

- 1 2 Pages 152–156 (Section: Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)) in: Elizabeth D Agabegi; Agabegi, Steven S. (2008). Step-Up to Medicine (Step-Up Series). Hagerstwon, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-7153-6.

- ↑ Feller M, Huwiler K, Schoepfer A, Shang A, Furrer H, Egger M (2010). "Long-term antibiotic treatment for Crohn's disease: systematic review and meta-analysis of placebo-controlled trials". Clin. Infect. Dis. 50 (4): 473–80. doi:10.1086/649923. PMID 20067425.

- ↑ Section "Antibiotics and Ulcerative Colitis" in: Prantera C, Scribano ML (2009). "Antibiotics and probiotics in inflammatory bowel disease: why, when, and how". Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 25 (4): 329–33. doi:10.1097/MOG.0b013e32832b20bf. PMID 19444096.

- ↑ Abreu, MT; Plevy, S; Sands, BE; Weinstein, R (2007). "Selective leukocyte apheresis for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 41 (10): 874–88. doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e3180479435. PMID 18090155.

- ↑ Vernia, P; D'Ovidio, V; Meo, D (October 2010). "Leukocytapheresis in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: Current position and perspectives". Transfusion and Apheresis Science. 43 (2): 227–9. doi:10.1016/j.transci.2010.07.023. PMID 20817610.

- ↑ Fedorak Richard (2010). "Probiotics in the Management of Ulcerative Colitis". Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 6 (11): 688–90. PMC 3033537

. PMID 21437015.

. PMID 21437015. - ↑ Northwestern University (2011). "New Probiotics Combats Inflammatory Bowel Disease". Science Daily.

- ↑ Borody TJ, Brandt LJ, Paramsothy S (January 2014). "Therapeutic faecal microbiota transplantation: current status and future developments". Current Opinion in Gastroenterology. 30 (1): 97–105. doi:10.1097/MOG.0000000000000027. PMC 3868025

. PMID 24257037.

. PMID 24257037. - ↑ Borody TJ, Warren EF, Leis S, Surace R, Ashman O (2003). "Treatment of ulcerative colitis using fecal bacteriotherapy" (PDF). Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 37 (1): 42–7. doi:10.1097/00004836-200307000-00012. PMID 12811208.

- ↑ Bensoussan M, Jovenin N, Garcia B, Vandromme L, Jolly D, Bouché O, Thiéfin G, Cadiot G (January 2006). "Complementary and alternative medicine use by patients with inflammatory bowel disease: results from a postal survey" (PDF). Gastroentérologie Clinique et Biologique. 30 (1): 14–23. doi:10.1016/S0399-8320(06)73072-X. PMID 16514377.

- ↑ Shah S (2007). "Dietary factors in the modulation of inflammatory bowel disease activity". Medscape General Medicine. 9 (1): 60. PMC 1925010

. PMID 17435660.

. PMID 17435660. - ↑ Terry PD, Villinger F, Bubenik GA, Sitaraman SV (January 2009). "Melatonin and ulcerative colitis: evidence, biological mechanisms, and future research". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 15 (1): 134–40. doi:10.1002/ibd.20527. PMID 18626968.

- ↑ Akhtar MS, Munir M (November 1989). "Evaluation of the gastric anti-ulcerogenic effects of Solanum nigrum, Brassica oleracea and Ocimum basilicum in rats". Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 27 (1–2): 163–76. doi:10.1016/0378-8741(89)90088-3. PMID 2515396.

Brassica oleracea (leaf) powder did not affect the ulcer index significantly but its aqueous extract lowered the index and increased hexosamine levels, suggesting gastric mucosal protection.

- ↑ "Fish oil". MedlinePlus.

- ↑ Del Pinto R, Pietropaoli D, Chandar AK, Ferri C, Cominelli F (April 2015). "Association Between Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Vitamin D Deficiency: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 21 (11): 2708–17. doi:10.1097/MIB.0000000000000546. PMC 4615394

. PMID 26348447.

. PMID 26348447. - ↑ Scheppach W, Sommer H, Kirchner T, Paganelli GM, Bartram P, Christl S, Richter F, Dusel G, Kasper H (July 1992). "Effect of butyrate enemas on the colonic mucosa in distal ulcerative colitis". Gastroenterology. 103 (1): 51–6. PMID 1612357.

- ↑ Brzezinski A, Rankin GB, Seidner DL, Lashner BA (1995). "Use of old and new oral 5-aminosalicylic acid formulations in inflammatory bowel disease". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine. 62 (5): 317–23. doi:10.3949/ccjm.62.5.317. PMID 7586488.

- ↑ Salim AS (1992). "Role of sulphydryl-containing agents in the management of recurrent attacks of ulcerative colitis. A new approach". Pharmacology. 45 (6): 307–18. doi:10.1159/000139016. PMID 1362613.

- ↑ Khan WI, Blennerhasset PA, Varghese AK, Chowdhury SK, Omsted P, Deng Y, Collins SM (2002). "Intestinal nematode infection ameliorates experimental colitis in mice". Infection and Immunity. 70 (11): 5931–7. doi:10.1128/iai.70.11.5931-5937.2002. PMC 130294

. PMID 12379667.

. PMID 12379667. - ↑ Melon A, Wang A, Phan V, McKay DM (2010). "Infection with Hymenolepis diminuta is more effective than daily corticosteroids in blocking chemically induced colitis in mice". Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2010: 384523. doi:10.1155/2010/384523. PMC 2789531

. PMID 20011066.

. PMID 20011066. - ↑ Broadhurst MJ, Ardeshir A, Kanwar B, Mirpuri J, Gundra UM, Leung JM, Wiens KE, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Kim CC, Yarovinsky F, Lerche NW, McCune JM, Loke P (2012). "Therapeutic helminth infection of macaques with idiopathic chronic diarrhea alters the inflammatory signature and mucosal microbiota of the colon". PLoS Pathogens. 8 (11): e1003000. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003000. PMC 3499566

. PMID 23166490.

. PMID 23166490. - ↑ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF, Thompson RA, Weinstock JV (2005). "Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: A randomized controlled trial". Gastroenterology. 128 (4): 825–832. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.005. PMID 15825065.

- ↑ Kumar, Sushil; Ahuja, Vineet; Sankar, Mari Jeeva; Kumar, Atul; Moss, Alan C. (2012-10-17). "Curcumin for maintenance of remission in ulcerative colitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD008424. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008424.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 4001731

. PMID 23076948.

. PMID 23076948. - ↑ Greenstein AJ, Janowitz HD, Sachar DB (September 1976). "The extra-intestinal complications of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis: a study of 700 patients". Medicine (Baltimore). 55 (5): 401–12. doi:10.1097/00005792-197609000-00004. PMID 957999.

- ↑ Leighton JA, Shen B, Baron TH, Adler DG, Davila R, Egan JV, Faigel DO, Gan SI, Hirota WK, Lichtenstein D, Qureshi WA, Rajan E, Zuckerman MJ, VanGuilder T, Fanelli RD (2006). "ASGE guideline: endoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of inflammatory bowel disease". Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. 63 (4): 558–65. doi:10.1016/j.gie.2006.02.005. PMID 16564852.

- ↑ Olsson R, Danielsson A, Järnerot G, Lindström E, Lööf L, Rolny P, Rydén BO, Tysk C, Wallerstedt S (1991). "Prevalence of primary sclerosing cholangitis in patients with ulcerative colitis". Gastroenterology. 100 (5 Pt 1): 1319–23. PMID 2013375.

- ↑ Jess T, Gamborg M, Munkholm P, Sørensen TI (March 2007). "Overall and cause-specific mortality in ulcerative colitis: meta-analysis of population-based inception cohort studies". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 102 (3): 609–17. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01000.x. PMID 17156150.

- ↑ Page 481 in: Colonic diseases. By Timothy R. Koch. 2003. ISBN 978-0-89603-961-2

- ↑ Büsch, K.; Ludvigsson, J. F.; Ekström-Smedby, K.; Ekbom, A.; Askling, J.; Neovius, M. (2014-01-01). "Nationwide prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in Sweden: a population-based register study". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 39 (1): 57–68. doi:10.1111/apt.12528. ISSN 1365-2036. PMID 24127738.

- ↑ Podolsky DK (2002). "Inflammatory bowel disease". The New England Journal of Medicine. 347 (6): 417–29. doi:10.1056/NEJMra020831. PMID 12167685.

- ↑ Shivananda S, Lennard-Jones J, Logan R, Fear N, Price A, Carpenter L, van Blankenstein M (1996). "Incidence of inflammatory bowel disease across Europe: is there a difference between north and south? Results of the European Collaborative Study on Inflammatory Bowel Disease (EC-IBD)" (PDF). Gut. 39 (5): 690–7. doi:10.1136/gut.39.5.690. PMC 1383393

. PMID 9014768.

. PMID 9014768. - ↑ Sonnenberg A, McCarty DJ, Jacobsen SJ (January 1991). "Geographic variation of inflammatory bowel disease within the United States". Gastroenterology. 100 (1): 143–9. PMID 1983816.

- ↑ Andersson RE, Olaison G, Tysk C, Ekbom A (March 2001). "Appendectomy and protection against ulcerative colitis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (11): 808–14. doi:10.1056/NEJM200103153441104. PMID 11248156.

- 1 2 Boyko EJ, Koepsell TD, Perera DR, Inui TS (March 1987). "Risk of ulcerative colitis among former and current cigarette smokers". The New England Journal of Medicine. 316 (12): 707–10. doi:10.1056/NEJM198703193161202. PMID 3821808.

- ↑ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF, Thompson RA, Weinstock JV (April 2005). "Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial" (PDF). Gastroenterology. 128 (4): 825–32. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.005. PMID 15825065. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Summers RW, Elliott DE, Urban JF, Thompson RA, Weinstock JV (2005). "Trichuris suis therapy for active ulcerative colitis: a randomized controlled trial". Gastroenterology. 128 (4): 825–32. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2005.01.005. PMID 15825065.

- 1 2 Bennett CF, Condon TC, Grimm S, Chan H, Chiang MY (1994). "Inhibition of endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion molecule expression with antisense oligonucleotides". The Journal of Immunology. 152 (1): 3530–40.

- ↑ Jones SC, Banks RE, Haidar A, Gearing AJ, Hemingway IK, Ibbotson SH, Dixon MF, Axon AT (1995). "Adhesion molecules in inflammatory bowel disease". Gut. 36 (5): 724–30. doi:10.1136/gut.36.5.724. PMC 1382677

. PMID 7541009.

. PMID 7541009. - ↑ van Deventer SJ, Wedel MK, Baker BF, Xia S, Chuang E, Miner PB (2006). "A Phase II dose ranging, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of alicaforsen enema in subjects with acute exacerbation of mild to moderate left-sided ulcerative colitis". Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 23 (10): 1415–25. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02910.x. PMID 16669956.

- ↑ Ghouri, Yezaz A; Richards, David M; Rahimi, Erik F; Krill, Joseph T; Jelinek, Katherine A; DuPont, Andrew W (9 December 2014). "Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics in inflammatory bowel disease". Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 7: 473–487. doi:10.2147/CEG.S27530. PMC 4266241

. PMID 25525379.

. PMID 25525379.

External links

- Ulcerative colitis at DMOZ

- MedlinePlus ulcerative colitis page

- Ulcerative colitis information page at Crohn's & Colitis Foundation of America

- Torpy JM, Lynm C, Golub RM (2012). "JAMA patient page. Ulcerative colitis" (PDF). JAMA. 307 (1): 104. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1889. PMID 22215172.