Small intestine

| Small Intestine | |

|---|---|

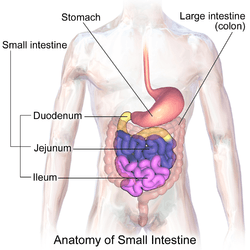

Diagram showing the small intestine and surrounding structures | |

| Details | |

| Artery | Superior mesenteric artery |

| Vein | Hepatic portal vein |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Lymph | Intestinal lymph trunk |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Intestinum tenue |

| MeSH | A03.556.124.684 |

| Code | 4453467 |

| TA | A05.6.01.001 |

| FMA | 7200 |

The small intestine or small bowel is the part of the gastrointestinal tract between the stomach and the large intestine, and is where most of the end absorption of food takes place. The small intestine has three distinct regions – the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum. The duodenum receives bile and pancreatic juice through the pancreatic duct, controlled by the sphincter of Oddi. The primary function of the small intestine is the absorption of nutrients and minerals from food.[2]

This article is primarily about the human gastrointestinal tract. The information about its processes is directly applicable to most placental mammals. A major exception to this is the digestive process in ruminants – notably cows. In invertebrates such as worms, the term "large intestine" is often used to describe the entire gastrointestinal tract.

Structure

Size

The length of the small intestine can vary greatly, from as short as 2.75 m (9.0 ft) to as long as 10.49 m (34.4 ft).[3] On average it is about 6.1 m (20 ft).[4] The length depends both on how tall the person is and how the length is measured.[3] Taller people generally have a longer small intestine and measurements are generally longer after death and when the bowel is empty.[3]

It is approximately 2.5–3 cm (1 inch) in diameter. The surface area of the human small intestinal mucosa, due to enlargement caused by folds, villi and microvilli, averages 30 square meters.[5]

Parts

The small intestine is divided into three structural parts.

- The duodenum is a short structure (about 20–25 cm long) continuous with the stomach and shaped like a "C".[6] It surrounds the head of the pancreas. It receives gastric chyme from the stomach, together with digestive juices from the pancreas (digestive enzymes) and the liver (bile). The digestive enzymes break down proteins and bile and emulsify fats into micelles. The duodenum contains Brunner's glands, which produce a mucus-rich alkaline secretion containing bicarbonate. These secretions, in combination with bicarbonate from the pancreas, neutralize the stomach acids contained in gastric chyme.

- The jejunum is the midsection of the small intestine, connecting the duodenum to the ileum. It is about 2.5 m long, and contains the plicae circulares, and villi that increase its surface area. Products of digestion (sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids) are absorbed into the bloodstream here. The suspensory muscle of duodenum marks the division between the duodenum and the jejunum.

- The ileum: The final section of the small intestine. It is about 3 m long, and contains villi similar to the jejunum. It absorbs mainly vitamin B12 and bile acids, as well as any other remaining nutrients. The ileum joins to the cecum of the large intestine at the ileocecal junction.

The jejunum and ileum are suspended in the abdominal cavity by mesentery. The mesentery is part of the peritoneum. Arteries, veins, lymph vessels and nerves travel within the mesentery.[7]

Blood supply

The small intestine receives a blood supply from the coeliac trunk and the superior mesenteric artery. These are both branches of the aorta. The duodenum receives blood from the coeliac trunk via the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery and from the superior mesenteric artery visa the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. These two arteries both have anterior and posterior branches that meet in the midline and anastomose. The jejunum and ileum receive blood from the superior mesenteric artery.[8] Branches of the superior mesenteric artery form a series of arches within the mesentery known as arterial arcades, which may be several layers deep. Straight blood vessels known as vasa recta travel from the arcades closest to the ileum and jejunum to the organs themselves.[8]

Histology

The three sections of the small intestine look similar to each other at a microscopic level, but there are some important differences. The parts of the intestine are as follows:

| Layer | Duodenum | Jejunum | Ileum |

|---|---|---|---|

| serosa | 1st part serosa, 2nd–4th adventitia | normal | normal |

| muscularis externa | longitudinal and circular layers, with Auerbach's (myenteric) plexus in between | same as duodenum | same as duodenum |

| submucosa | Brunner's glands and Meissner's (submucosal) plexus | no BG | no BG |

| mucosa: muscularis mucosae | normal | normal | normal |

| mucosa: lamina propria | no PP | no PP | Peyer's patches |

| mucosa: intestinal epithelium | simple columnar. Contains goblet cells, Paneth cells | Similar to duodenum | ? |

Development

The small intestine develops from the midgut of the primitive gut tube.[9] By the fifth week of embryological life, the ileum begins to grow longer at a very fast rate, forming a U-shaped fold called the primary intestinal loop. The loop grows so fast in length that it outgrows the abdomen and protrudes through the umbilicus. By week 10, the loop retracts back into the abdomen. Between weeks six and ten the small intestine rotates anticlockwise, as viewed from the front of the embryo. It rotates a further 180 degrees after it has moved back into the abdomen. This process creates the twisted shape of the large intestine.[9]

Function

Food from the stomach is allowed into the duodenum through the pylorus by a muscle called the pyloric sphincter.

Digestion

The small intestine is where most chemical digestion takes place. Many of the digestive enzymes that act in the small intestine are secreted by the pancreas and liver and enter the small intestine via the pancreatic duct. Pancreatic enzymes and bile from the gallbladder enter the small intestine in response to the hormone cholecystokinin, which is produced in the small intestine in response to the presence of nutrients. Secretin, another hormone produced in the small intestine, causes additional effects on the pancreas, where it promotes the release of bicarbonate into the duodenum in order to neutralize the potentially harmful acid coming from the stomach.

The three major classes of nutrients that undergo digestion are proteins, lipids (fats) and carbohydrates:

- Proteins are degraded into small peptides and amino acids before absorption.[10] Chemical breakdown begins in the stomach and continues in the small intestine. Proteolytic enzymes, including trypsin and chymotrypsin, are secreted by the pancreas and cleave proteins into smaller peptides. Carboxypeptidase, which is a pancreatic brush border enzyme, splits one amino acid at a time. Aminopeptidase and dipeptidase free the end amino acid products.

- Lipids (fats) are degraded into fatty acids and glycerol. Pancreatic lipase breaks down triglycerides into free fatty acids and monoglycerides. Pancreatic lipase works with the help of the salts from the bile secreted by the liver and stored in the gall bladder. Bile salts attach to triglycerides to help emulsify them, which aids access by pancreatic lipase. This occurs because the lipase is water-soluble but the fatty triglycerides are hydrophobic and tend to orient towards each other and away from the watery intestinal surroundings. The bile salts emulsify the triglycerides in the watery surroundings until the lipase can break them into the smaller components that are able to enter the villi for absorption.

- Some carbohydrates are degraded into simple sugars, or monosaccharides (e.g., glucose). Pancreatic amylase breaks down some carbohydrates (notably starch) into oligosaccharides. Other carbohydrates pass undigested into the large intestine and further handling by intestinal bacteria. Brush border enzymes take over from there. The most important brush border enzymes are dextrinase and glucoamylase, which further break down oligosaccharides. Other brush border enzymes are maltase, sucrase and lactase. Lactase is absent in some adult humans and, for them, lactose, like most poly-saccharides, is not digested in the small intestine. Some carbohydrates, such as cellulose, are not digested at all, despite being made of multiple glucose units. This is because the cellulose is made out of beta-glucose, making the inter-monosaccharidal bindings different from the ones present in starch, which consists of alpha-glucose. Humans lack the enzyme for splitting the beta-glucose-bonds, something reserved for herbivores and bacteria from the large intestine.

Absorption

Digested food is now able to pass into the blood vessels in the wall of the intestine through either diffusion or active transport. The small intestine is the site where most of the nutrients from ingested food are absorbed. The inner wall, or mucosa, of the small intestine is lined with simple columnar epithelial tissue. Structurally, the mucosa is covered in wrinkles or folds called plicae circulares, which are considered permanent features in the wall of the organ. They are distinct from rugae which are considered non-permanent or temporary allowing for distention and contraction. From the plicae circulares project microscopic finger-like pieces of tissue called villi (Latin for "shaggy hair"). The individual epithelial cells also have finger-like projections known as microvilli. The functions of the plicae circulares, the villi, and the microvilli are to increase the amount of surface area available for the absorption of nutrients, and to limit the loss of said nutrients to intestinal fauna.

Each villus has a network of capillaries and fine lymphatic vessels called lacteals close to its surface. The epithelial cells of the villi transport nutrients from the lumen of the intestine into these capillaries (amino acids and carbohydrates) and lacteals (lipids). The absorbed substances are transported via the blood vessels to different organs of the body where they are used to build complex substances such as the proteins required by our body. The material that remains undigested and unabsorbed passes into the large intestine.

Absorption of the majority of nutrients takes place in the jejunum, with the following notable exceptions:

- Iron is absorbed in the duodenum.

- Vitamin B12 and bile salts are absorbed in the terminal ileum.

- Water and lipids are absorbed by passive diffusion throughout the small intestine.

- Sodium bicarbonate is absorbed by active transport and glucose and amino acid co-transport.

- Fructose is absorbed by facilitated diffusion.

Immunological

The small intestine supports the body's immune system.[11] The presence of probiotic gut flora appears to contribute positively to the host's immune system. Peyer's patches, located within the ileum of the small intestine, are an important part of the digestive tract's local immune system. They are part of the lymphatic system, and provide a site for antigens from potentially harmful bacteria or other microorganisms in the digestive tract to be sampled, and subsequently presented to the immune system.[12]

Clinical significance

The small intestine is a complex organ, and as such, there are a very large number of possible conditions that may affect the function of the small bowel. A few of them are listed below, some of which are common, with up to 10% of people being affected at some time in their lives, while others are vanishingly rare.

- Small intestine obstruction or obstructive disorders

- Paralytic ileus

- Volvulus

- Hernia

- Adhesions

- Obstruction from external pressure

- Obstruction by masses in the lumen (foreign bodies, bezoar, gallstones)

- Infectious diseases

- Giardiasis

- Ascariasis

- Tropical sprue

- Tape worm (Diphyllobothrium latum, Taenia solium, Hymenolepsis nana)

- Hookworm (e.g. Necator americanus, Ancylostoma duodenale)

- Nematodes (e.g. Ascaris lumbricoides)

- Other Protozoa (e.g. Cryptosporidium parvum, Cyclospora, Microsporidia, Entamoeba histolytica)

- Bacterial infections

- Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- Salmonella enterica

- Campylobacter

- Shigella

- Yersinia

- Clostridium difficile (antibiotic-associated colitis, Pseudomembranous colitis)

- Mycobacterium (disseminated Mycobacterium tuberculosis)

- Whipple's disease

- Vibrio (cholera)

- Enteric (typhoid) fever (Salmonella enterica var. typhii) and paratyphoid fever

- Bacillus cereus

- Clostridium perfringens (gas gangrene)

- Viral infections

- Neoplasms (cancers)

- Adenocarcinoma

- Carcinoid

- Gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST)

- Lymphoma

- Sarcoma

- Leiomyoma

- Metastatic tumors, especially SCLC or melanoma

- Developmental, congenital or genetic conditions

- Duodenal (intestinal) atresia

- Hirschsprung's disease

- Meckel's diverticulum

- Pyloric stenosis

- Pancreas divisum

- Ectopic pancreas

- Enteric duplication cyst

- Situs inversus

- Cystic fibrosis

- Malrotation

- Persistent urachus

- Omphalocele

- Gastroschisis

- Disaccharidase (lactase) deficiencies

- Primary bile acid malabsorption

- Gardner syndrome

- Familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome (FAP)

- Other conditions

- Crohn's disease, and the more general inflammatory bowel disease

- Typhlitis (neutropenic colitis in the immunosuppressed

- Coeliac disease (sprue or non-tropical sprue)

- Mesenteric ischemia

- Embolus or thrombus of the superior mesenteric artery or the superior mesenteric vein

- Arteriovenous malformation

- Gastric dumping syndrome

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Duodenal (peptic) ulcers

- Gastrointestinal perforation

- Hyperthyroidism

- Diverticulitis

- Radiation enterocolitis

- Mesenteric cysts

- Peritoneal Infection

- Sclerosing retroperitonitis

- Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth

Other animals

The small intestine is found in all tetrapods and also in teleosts, although its form and length vary enormously between species. In teleosts, it is relatively short, typically around one and a half times the length of the fish's body. It commonly has a number of pyloric caeca, small pouch-like structures along its length that help to increase the overall surface area of the organ for digesting food. There is no ileocaecal valve in teleosts, with the boundary between the small intestine and the rectum being marked only by the end of the digestive epitheliu [13]

In tetrapods, the ileocaecal valve is always present, opening into the colon. The length of the small intestine is typically longer in tetrapods than in teleosts, but is especially so in herbivores, as well as in mammals and birds, which have a higher metabolic rate than amphibians or reptiles. The lining of the small intestine includes microscopic folds to increase its surface area in all vertebrates, but only in mammals do these develop into true villi.[13]

The boundaries between the duodenum, jejunum, and ileum are somewhat vague even in humans, and such distinctions are either ignored when discussing the anatomy of other animals, or are essentially arbitrary.[13]

There is no small intestine as such in non-teleost fish, such as sharks, sturgeons, and lungfish. Instead, the digestive part of the gut forms a spiral intestine, connecting the stomach to the rectum. In this type of gut, the intestine itself is relatively straight, but has a long fold running along the inner surface in a spiral fashion, sometimes for dozens of turns. This valve greatly increases both the surface area and the effective length of the intestine. The lining of the spiral intestine is similar to that of the small intestine in teleosts and non-mammalian tetrapods.[13]

In lampreys, the spiral valve is extremely small, possibly because their diet requires little digestion. Hagfish have no spiral valve at all, with digestion occurring for almost the entire length of the intestine, which is not subdivided into different regions.[13]

Society and culture

In traditional Chinese medicine, the small intestine is a yang organ.[14]

Additional images

-

Small intestine in situ, greater omentum folded upwards.

-

Third state of the development of the intestinal canal and peritoneum, seen from in front (diagrammatic). The mode of preparation is the same as in Fig 400

-

Second stage of development of the intestinal canal and peritoneum, seen from in front (diagrammatic). The liver has been removed and the two layers of the ventral mesogastrium (lesser omentum) have been cut. The vessels are represented in black and the peritoneum in the reddish tint.

-

First stage of the development of the intestinal canal and the peritoneum, seen from the side (diagrammatic). From colon 1 the ascending and transverse colon will be formed and from colon 2 the descending and sigmoid colons and the rectum.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Small intestine. |

Notes and references

- ↑ Physiology: 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30 - Essentials of Human Physiology

- ↑ human body | Britannica.com

- 1 2 3 DiBaise, John K.; Parrish, Carol Rees; Thompson, Jon S. (2016). Short Bowel Syndrome: Practical Approach to Management. CRC Press. p. 31. ISBN 9781498720809.

- ↑ "Short Bowel Syndrome". NIDDK. July 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ↑ Helander, Herbert F; Fändriks, Lars (2015). "Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 49 (6): 681–689. doi:10.3109/00365521.2014.898326. ISSN 0036-5521. PMID 24694282.

- ↑ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 273. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. p. 271. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- 1 2 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 295–299. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- 1 2 Schoenwolf, Gary C.; Bleyl, Steven B.; Brauer, Philip R.; Francis-West, Philippa H. (2009). "Development of the Urogenital system". Larsen's human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. p. 237. ISBN 9780443068119.

- ↑ Silk DB (1974). "Progress report. Peptide absorption in man". Gut. 15 (6): 494–501. doi:10.1136/gut.15.6.494. PMC 1413009

. PMID 4604970.

. PMID 4604970. - ↑ "Intestinal immune cells play an unexpected role in immune surveillance of the bloodstream". Massachusetts General Hospital. 13 December 2012.

- ↑ Canny, G. O.; McCormick, B. A. (2008). "Bacteria in the Intestine, Helpful Residents or Enemies from Within?". Infection and Immunity. 76 (8): 3360–3373. doi:10.1128/IAI.00187-08. ISSN 0019-9567.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 349–353. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

- ↑ Porter [ed.], Roy (1997). Medicine : a history of healing. [S.l.]: Diane Pub Co. p. 104. ISBN 9780756751432.

Bibliography

- Sherwood, Lauralee (2006). Fundamentals of physiology: a human perspective (Third ed.). Florence, KY: Cengage Learning. p. 768. ISBN 0-534-46697-4.

- Solomon et al. (2002) Biology Sixth Edition, Brooks-Cole/Thomson Learning ISBN 0-03-033503-5

- Townsend et al. (2004) Sabiston Textbook of Surgery, Elsevier ISBN 0-7216-0409-9

- Thomson A, Drozdowski L, Iordache C, Thomson B, Vermeire S, Clandinin M, Wild G (2003). "Small bowel review: Normal physiology, part 1.". Dig Dis Sci. 48 (8): 1546–64. doi:10.1023/A:1024719925058. PMID 12924651.

- Thomson A, Drozdowski L, Iordache C, Thomson B, Vermeire S, Clandinin M, Wild G (2003). "Small bowel review: Normal physiology, part 2.". Dig Dis Sci. 48 (8): 1565–81. doi:10.1023/A:1024724109128. PMID 12924652.