Pancreas

| Pancreas | |

|---|---|

Anatomy of the pancreas | |

1: Head of pancreas 2: Uncinate process of pancreas 3: Pancreatic notch 4: Body of pancreas 5: Anterior surface of pancreas 6: Inferior surface of pancreas 7: Superior margin of pancreas 8: Anterior margin of pancreas 9: Inferior margin of pancreas 10: Omental tuber 11: Tail of pancreas 12: Duodenum | |

| Details | |

| Precursor | Pancreatic buds |

| Artery | Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery, splenic artery |

| Vein | Pancreaticoduodenal veins, pancreatic veins |

| Nerve | Pancreatic plexus, celiac ganglia, vagus nerve[1] |

| Lymph | Splenic lymph nodes, celiac lymph nodes and superior mesenteric lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Pancreas |

| Greek | Pankrèous |

| MeSH | A03.734 |

| TA | A05.9.01.001 |

| FMA | 7198 |

The pancreas /ˈpæŋkriəs/ is a glandular organ in the digestive system and endocrine system of vertebrates. In humans, it is located in the abdominal cavity behind the stomach. It is an endocrine gland producing several important hormones, including insulin, glucagon, somatostatin, and pancreatic polypeptide which circulate in the blood. The pancreas is also a digestive organ, secreting pancreatic juice containing digestive enzymes that assist digestion and absorption of nutrients in the small intestine. These enzymes help to further break down the carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids in the chyme.

Structure

9. Gallbladder, 10–11. Right and left lobes of liver. 12. Spleen.

13. Esophagus. 14. Stomach. 15. Pancreas: 16: Accessory pancreatic duct, 17: Pancreatic duct.

18. Small intestine: 19. Duodenum, 20. Jejunum

21–22: Right and left kidneys (silhouette).

The anterior border of the liver is lifted upwards (brown arrow). Gallbladder with Longitudinal section, pancreas and duodenum with frontal one. Intrahepatic ducts and stomach in transparency.

The pancreas is an endocrine organ that lies in the upper left part of the abdomen. It is found behind the stomach.[2] The pancreas is about 15 cm (6 in) long.[3]

Anatomically, the pancreas is divided into the head of pancreas, the neck of pancreas, the body of pancreas, and the tail of pancreas. The head is surrounded by the duodenum in its concavity. The head surrounds two blood vessels, the superior mesenteric artery and vein. From the back of the head emerges a small uncinate process which extends to the back of the superior mesenteric vein and ends at the superior mesenteric artery.[4] The neck is about 2.5 cm long and lies between the head and the body, and in front of the superior mesenteric artery and vein. Its front upper surface supports the pylorus (the base) of the stomach. The neck arises from the left upper part of the front of the head. It is directed at first, upward and forward, and then upward and to the left to join the body; it is somewhat flattened from above downward and backward. On the right it is grooved by the gastroduodenal artery. The body is the largest part of the pancreas and lies behind the pylorus, at the same level as the transpyloric plane.[5] The tail ends by abutting the spleen.

The pancreas is a secretory structure with an internal hormonal role (endocrine) and an external digestive role (exocrine). It has two main ducts, the main pancreatic duct, and the accessory pancreatic duct. These drain enzymes through the ampulla of Vater into the duodenum.[6]

Margins

The upper margin of the pancreas is blunt and flat to the right; narrow and sharp to the left, near the tail.

It begins on the right in the omental tuber, and is in relation with the celiac artery, from which the hepatic artery courses to the right just above the gland, while the splenic artery runs toward the left in a groove along this border.

The lower margin of the pancreas separates the posterior from the inferior surface; the superior mesenteric vessels emerge under its right extremity.

The frontal margin of the pancreas separates the anterior from the inferior surface of the pancreas, and along this border the two layers of the transverse mesocolon diverge from one another; one passing upward over the frontal surface, the other backward over the inferior surface.

Surfaces

The inferior surface of the pancreas is narrow on the right but broader on the left, and is covered by peritoneum; it lies upon the duodenojejunal flexure and on some coils of the jejunum; its left extremity rests on the splenic flexure of the colon.

The anterior surface of the pancreas faces the front of the abdomen. Most of the right half of this surface is in contact with the transverse colon, with only areolar tissue intervening.

From its upper part it joins to the neck of the pancreas at a well-marked prominence, the omental tuber which abuts the lesser omentum. Its right edge is marked by a groove for the gastroduodenal artery.

The lower part of the right half, below the transverse colon, is covered by peritoneum continuous with the inferior layer of the transverse mesocolon, and is in contact with the coils of the small intestine.

The superior mesenteric artery passes down in front of the left half across the uncinate process; the superior mesenteric vein runs upward on the right side of the artery and, behind the neck, joins with the lienal vein to form the portal vein.

Blood supply

The pancreas receives blood from branches of both the coeliac artery and superior mesenteric artery. The splenic artery runs along the top margin of the pancreas, and supplies the neck, body and tail of the pancreas through its pancreatic branches, the largest of which is called the greater pancreatic artery. The superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries run along the anterior and posterior surfaces of the head of the pancreas at its border with the duodenum. These supply the head of the pancreas.[4]

The body and neck of the pancreas drain into the splenic vein; the head drains into the superior mesenteric and portal veins.[4]

Histology

The pancreas contains tissue with an endocrine and exocrine role, and this division is also visible when the pancreas is viewed under a microscope.[6]

The tissues with an endocrine role can be seen under staining as lightly-stained clusters of cells, called pancreatic islets (also called islets of Langerhans).[6]

Darker-staining cells form clusters called acini, which are arranged in lobes separated by a thin fibrous barrier. The secretory cells of each acinus surround a small intercalated duct. Because of their secretory function, these cells have many small granules of zymogens that are visible. The intercalated ducts drain into larger ducts within the lobule, and finally interlobular ducts. The ducts are lined by a single layer of columnar epithelium. With increasing diameter, several layers of columnar cells may be seen.[6]

Variation

The size of the pancreas varies considerably.[2] Several anatomical variations exist, relating to the embryological development of the two pancreatic buds. The pancreas develops from these buds on either side of the duodenum. The ventral bud eventually rotates to lie next to the dorsal bud, eventually fusing. If the two buds each having a duct, do not fuse, a pancreas may exist with two separate ducts, a condition known as a pancreas divisum. This condition has no physiologic consequence.[7] If the ventral bud does not fully rotate, an annular pancreas may exist. This is where sections of the pancreas completely encircle the duodenum, and may even lead to duodenal atresia.[4]

An accessory pancreatic duct may exist if the main duct of pancreas does not regress.[8]

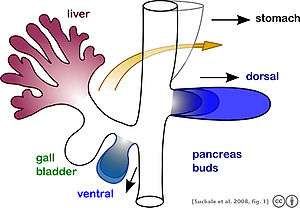

Development

As part of embryonic development the pancreas forms from the embryonic foregut and is therefore of endodermal origin. Pancreatic development begins with the formation of a ventral and a dorsal pancreatic bud. Each structure communicates with the foregut through a duct. The dorsal pancreatic bud forms the head, neck, body, and tail, whereas the ventral pancreatic bud forms the uncinate process.[8]

Differential rotation and fusion of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds results in the formation of the definitive pancreas.[9] As the duodenum rotates to the right, it carries with it the ventral pancreatic bud and common bile duct. Upon reaching its final destination, the ventral pancreatic bud fuses with the much larger dorsal pancreatic bud. At this point of fusion, the main ducts of the ventral and dorsal pancreatic buds fuse, forming the main pancreatic duct. The duct of the dorsal bud regresses, leaving the main pancreatic duct.[8]

Differentiation of cells of the pancreas proceeds through two different pathways, corresponding to the dual endocrine and exocrine functions of the pancreas. In progenitor cells of the exocrine pancreas, important molecules that induce differentiation include follistatin, fibroblast growth factors, and activation of the Notch receptor system.[9] Development of the exocrine acini progresses through three successive stages. These are the predifferentiated, protodifferentiated, and differentiated stages, which correspond to undetectable, low, and high levels of digestive enzyme activity, respectively.

The multipotent pancreatic progenitor cells have the capacity to differentiate into any of the pancreatic cells: acinar cells, endocrine cells, and ductal cells. These progenitor cells are characterised by the co-expression of the transcription factors PDX1 and NKX6-1. Under the influence of neurogenin-3 and ISL1, but in the absence of notch receptor signaling, these cells differentiate to form two lines of committed endocrine precursor cells. The first line, under the direction of a Pax gene, forms α- and γ- cells, which produce glucagon and pancreatic polypeptides, respectively. The second line, influenced by Pax-6, produces beta cells (β-) and delta cells (δ-), which secrete insulin and somatostatin, respectively.

Insulin and glucagon can be detected in the human fetal circulation by the fourth or fifth month of fetal development.[9]

Function

The pancreas is involved in blood sugar control and metabolism within the body, and also in the secretion of substances which help digestion. Classically, these are divided into an "endocrine" role, relating to the secretion of insulin and other substances within pancreatic islets and helping control blood sugar levels and metabolism within the body, and an "exocrine" role, relating to the secretion of enzymes involved in digesting substances from outside of the body.

Sugar control and metabolism

Approximately 3 million cell clusters called pancreatic islets are present in the pancreas.[10] Within these islets are four types of cells which are involved in the regulation of blood glucose levels. Each type of cell secretes a different type of hormone: α alpha cells secrete glucagon (increase glucose in blood), β beta cells secrete insulin (decrease glucose in blood), δ delta cells secrete somatostatin (regulates/stops α and β cells) and PP cells, or γ (gamma) cells, secrete pancreatic polypeptide.[11] These act to control blood glucose through secreting glucagon to increase the levels of glucose, and insulin to decrease it.

The islets are crisscrossed by a dense network of capillaries. The capillaries of the islets are lined by layers of islet cells, and most endocrine cells are in direct contact with blood vessels, either by cytoplasmic processes or by direct apposition. The islets function independently from the digestive role played by the majority of pancreatic cells.[12]

Activity of the cells in the islets is affected by the autonomic nervous system:

- Sympathetic (adrenergic)

- α2: decreases secretion from beta cells, increases secretion from alpha cells, β2: increases secretion from beta cells

- Parasympathetic (muscarinic)

- M3: increases stimulation of alpha cells and beta cells[13]

Digestion

The pancreas plays a vital role in the digestive system. It secretes fluid that contains enzymes into the duodenum. These enzymes help to break down carbohydrates (usually starch), proteins and lipids (fats). This role is called the "exocrine" role of the pancreas. Cells are arranged clusters called acini. Secretions into the middle of the acinus accumulate in intralobular ducts that drain to the main pancreatic duct, which drains directly into the duodenum.

The cells are filled with granules containing the digestive enzymes. These are secreted in an inactive form called (termed zymogens or proenzymes). When released into the duodenum, they are activated by the enzyme enteropeptidase present in the lining of the duodenum. The proenzymes are cleaved, creating a cascade of activating enzymes: enteropeptidase activates the proenzyme trypsinogen by cleaving it to form trypsin. The free trypsin then cleaves the rest of the trypsinogen, as well as chymotrypsinogen to its active form chymotrypsin.

The pancreas secretes substances which help in the digestion of starch and other carbohydrates, proteins and fats.[14] Proteases, the enzymes involved in the digestion of proteins, include trypsinogen and chymotrypsinogen. The enzyme involved in the digestion of fats is lipase. Amylase, also secreted by the pancreas, breaks down starch (amylum) and other carbohydrates. The pancreas also secretes phospholipase A2, lysophospholipase, and cholesterol esterase.

Secretion of these proenzymes is via the hormones gastrin, cholecystokinin and secretin, which are secreted by cells in the stomach and duodenum in response to distension and/or food.

Clinical significance

A perforation of the pancreas, which may lead to the secretion of digestive enzymes such as lipase and amylase into the abdominal cavity as well as subsequent pancreatic self-digestion and digestion and damage to organs within the abdomen, generally requires prompt and experienced medical intervention.

It is possible for one to live without a pancreas, provided that the person takes insulin for proper regulation of blood glucose concentration and pancreatic enzyme supplements to aid digestion.[15]

Inflammation

Inflammation of the pancreas is known as pancreatitis. Pancreatitis is most often associated with recurrent gallstones or chronic alcohol use, although a variety of other causes, including measles, mumps, some medications, the congenital condition alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and even some scorpion stings, may cause pancreatitis. Pancreatitis is likely to cause intense pain in the central abdomen, that often radiates to the back, and may be associated with jaundice. In addition, due to causing problems with fat digestion and bilirubin excretion, pancreatitis often presents with pale stools and dark urine.[16]

In pancreatitis, enzymes of the exocrine pancreas damage the structure and tissue of the pancreas. Detection of some of these enzymes, such as amylase and lipase in the blood, along with symptoms and findings on X-ray, are often used to indicate that a person has pancreatitis. A person with pancreatitis is also at risk of shock. Pancreatitis is often managed medically with analgesics, removal of gallstones or treatment of other causes, and monitoring to ensure a patient does not develop shock.[16]

Cancer

Pancreatic cancers, particularly the most common type, pancreatic adenocarcinoma, remain very difficult to treat, and are mostly diagnosed only at a stage that is too late for surgery, which is the only curative treatment. Pancreatic cancer is rare in those younger than 40, and the median age of diagnosis is 71.[17] Risk factors include smoking, obesity, diabetes, and certain rare genetic conditions including multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 and hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer among others.[18] About 25% of cases are attributable to tobacco smoking,[19] while 5-10% of cases are linked to inherited genes.[17]

There are several types of pancreatic cancer, involving both the endocrine and exocrine tissue. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma, which affects the exocrine part of the pancreas, is by far the most common form. The many types of pancreatic endocrine tumors are all uncommon or rare, and have varied outlooks. However the incidence of these cancers has been rising sharply; it is not clear to what extent this reflects increased detection, especially through medical imaging, of tumors that would be very slow to develop. Insulinomas (largely benign) and gastrinomas are the most common types.[20] In the United States pancreatic cancer is the fourth most common cause of deaths due to cancer.[21] The disease occurs more often in the developed world, which had 68% of new cases in 2012.[22] Pancreatic adenocarcinoma typically has poor outcomes with the average percentage alive for at least one and five years after diagnosis being 25% and 5% respectively.[22][23] In localized disease where the cancer is small (< 2 cm) the number alive at five years is approximately 20%.[24] For those with neuroendocrine cancers the number alive after five years is much better at 65%, varying considerably with type.[22]

A solid pseudopapillary tumour is a low-grade malignant tumour of the pancreas of papillary architecture that typically afflicts young women.[25]

Diabetes Mellitus

Type 1 diabetes

Diabetes mellitus type 1 is a chronic autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks the insulin-secreting cells of the pancreas. Insulin is needed to keep blood sugar levels within optimal ranges, and its lack can lead to high blood sugar. As an untreated chronic condition, diabetic neuropathy can result. Type 1 diabetes can develop at any age but is most often diagnosed before adulthood. For type 1 diabetics, insulin injections are critical for survival.[26]

An experimental procedure to treat type 1 diabetes is the transplantation of pancreatic islet cells from a donor into the patient's liver so that the cells can produce the deficient insulin.[27]

Type 2 diabetes

Diabetes mellitus type 2 is the most common form of diabetes. The causes for high blood sugar in this form of diabetes usually are a combination of insulin resistance and impaired insulin secretion, with both genetic and environmental factors playing an important role in the development of the disease. The management of type 2 diabetes relies on a series of changes in diet and physical activity with the purpose of reducing blood sugar levels to normal ranges and increasing insulin sensitivity.[26] Biguanides such as metformin are also used as part of the treatment along with insulin therapy.[28]

History

The pancreas was first identified by Herophilus (335–280 BC), a Greek anatomist and surgeon.[29] A few hundred years later, Rufus of Ephesus, another Greek anatomist, gave the pancreas its name. Etymologically, the term "pancreas", a modern Latin adaptation of Greek πάγκρεας,[30] [πᾶν ("all", "whole"), and κρέας ("flesh")],[31] originally means sweetbread,[32] although literally meaning all-flesh, presumably because of its fleshy consistency. It was only in 1889 when Oskar Minkowski discovered that removing the pancreas from a dog caused it to become diabetic (insulin was later discovered by Frederick Banting and Charles Herbert Best in 1921).

The organ is mentioned prominently in the 1992 film Encino Man. Pauly Shore's character Stoney often refers to the organ in unrelated contexts, perhaps demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of what the pancreas does.

Other animals

Pancreatic tissue is present in all vertebrates, but its precise form and arrangement varies widely. There may be up to three separate pancreases, two of which arise from ventral buds, and the other dorsally. In most species (including humans), these fuse in the adult, but there are several exceptions. Even when a single pancreas is present, two or three pancreatic ducts may persist, each draining separately into the duodenum (or equivalent part of the foregut). Birds, for example, typically have three such ducts.[33]

In teleosts, and a few other species (such as rabbits), there is no discrete pancreas at all, with pancreatic tissue being distributed diffusely across the mesentery and even within other nearby organs, such as the liver or spleen. In a few teleost species, the endocrine tissue has fused to form a distinct gland within the abdominal cavity, but otherwise it is distributed among the exocrine components. The most primitive arrangement, however, appears to be that of lampreys and lungfish, in which pancreatic tissue is found as a number of discrete nodules within the wall of the gut itself, with the exocrine portions being little different from other glandular structures of the intestine.[33]

Additional images

The duodenum and pancreas

The duodenum and pancreas Pancreas of a human embryo at end of sixth week

Pancreas of a human embryo at end of sixth week Dog pancreas magnified 100 times

Dog pancreas magnified 100 times The pancreas and its surrounding structures

The pancreas and its surrounding structures Duodenum and pancreas. Deep dissection.

Duodenum and pancreas. Deep dissection.

See also

References

This article incorporates text in the public domain from the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ↑ Physiology: 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30 - Essentials of Human Physiology

- 1 2 Khan, Ali Nawaz. "Chronic Pancreatitis Imaging". Medscape. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- ↑ "Cancer of the Pancreas". NHS. Retrieved 5 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. pp. 288–290, 297, 303. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Bålens ytanatomi (surface anatomy). Godfried Roomans, Mats Hjortberg and Anca Dragomir. Institution for Anatomy, Uppsala. 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Young, Barbara, ed. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas (5th ed.). Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 299–301. ISBN 978-0-443-06850-8.

- ↑ "Pancreatic Divisum: Background, Pathophysiology, Epidemiology".

- 1 2 3 Schoenwolf, Gary C. (2009). Larsen's human embryology (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 241–244. ISBN 978-0-443-06811-9.

- 1 2 3 Carlson, Bruce M. (2004). Human embryology and developmental biology. St. Louis: Mosby. pp. 372–4. ISBN 0-323-01487-9.

- ↑ Ionescu-Tirgoviste, Constantin; Gagniuc, Paul A.; Gubceac, Elvira; Mardare, Liliana; Popescu, Irinel; Dima, Simona; Militaru, Manuella (2015-09-29). "A 3D map of the islet routes throughout the healthy human pancreas". Scientific Reports. 5: 14634. doi:10.1038/srep14634. PMC 4586491

. PMID 26417671.

. PMID 26417671. - ↑ BRS physiology 4th edition ,page 255-256, Linda S. Constanzo, Lippincott publishing

- ↑ The Body, by Alan E. Nourse, (op. cit., p. 171.)

- ↑ Verspohl EJ, Tacke R, Mutschler E, Lambrecht G (1990). "Muscarinic receptor subtypes in rat pancreatic islets: binding and functional studies". Eur. J. Pharmacol. 178 (3): 303–311. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(90)90109-J. PMID 2187704.

- ↑ Hall, John (2011). Guyton and Hall textbook of medical physiology (12th ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Saunders/Elsevier. p. 781. ISBN 978-1-4160-4574-8.

- ↑ Banks, PA; Conwell, DL; Toskes, PP (2010). "The management of acute and chronic pancreatitis.". Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 6 (2 Suppl 3): 1–16. PMC 2886461

. PMID 20567557.

. PMID 20567557. - 1 2 Nicki R. Colledge; Brian R. Walker; Stuart H. Ralston, eds. (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. Illustrated by Robert Britton (21st ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 871–874. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- 1 2 Ryan DP, Hong TS, Bardeesy N (September 2014). "Pancreatic adenocarcinoma". N. Engl. J. Med. 371 (11): 1039–49. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1404198. PMID 25207767.

- ↑ "Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) Patient Version". National Cancer Institute. 2014-04-17. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Wolfgang, CL; Herman, JM; Laheru, DA; Klein, AP; Erdek, MA; Fishman, EK; Hruban, RH (Sep 2013). "Recent progress in pancreatic cancer.". CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 63 (5): 319. doi:10.3322/caac.21190. PMC 3769458

. PMID 23856911.

. PMID 23856911. - ↑ Burns, WR; Edil, BH (March 2012). "Neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors: guidelines for management and update.". Current treatment options in oncology. 13 (1): 24–34. doi:10.1007/s11864-011-0172-2. PMID 22198808.

- ↑ Hariharan D, Saied A, Kocher HM (2008). "Analysis of mortality rates for pancreatic cancer across the world". HPB. 10 (1): 58–62. doi:10.1080/13651820701883148. PMC 2504856

. PMID 18695761.

. PMID 18695761. - 1 2 3 World Cancer Report 2014. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.7. ISBN 9283204298.

- ↑ "American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts & Figures 2010: see page 4 for incidence estimates, and page 19 for survival percentages" (PDF).

- ↑ "Pancreatic Cancer Treatment (PDQ®) Health Professional Version". NCI. 2014-02-21. Retrieved 8 June 2014.

- ↑ Patil TB, Shrikhande SV, Kanhere HA, Saoji RR, Ramadwar MR, Shukla PJ (2006). "Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas: a single institution experience of 14 cases". HPB. 8 (2): 148–50. doi:10.1080/13651820510035721. PMC 2131425

. PMID 18333264.

. PMID 18333264. - 1 2 Melmed, S; Polonsky, KS; Larsen, PR; Kronenberg, HM (2011). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology (12th ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-1437703245.

- ↑ Lakey, JR; Burridge, PW; Shapiro, AM (September 2003). "Technical aspects of islet preparation and transplantation.". Transplant international : official journal of the European Society for Organ Transplantation. 16 (9): 613–32. PMID 12928769.

- ↑ Longo, D; Fauci, A; Kasper, D; Hauser, S; Jameson, J; Loscalzo, J (2012). Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 2995–3000. ISBN 978-0071748896.

- ↑ Howard, John M.; Hess, Walter (2012-12-06). History of the Pancreas: Mysteries of a Hidden Organ. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 24. ISBN 9781461505556.

- ↑ Terry O'Brien. A2Z Book of word Origins. Rupa Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-81-291-1809-7.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Pancreas". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2007-04-04.

- ↑ Tamara M. Green (2008). The Greek and Latin Roots of English. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-7425-4780-3.

- 1 2 Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 357–359. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

-

Media related to Pancreas at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pancreas at Wikimedia Commons