Eicosapentaenoic acid

| | |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

(5Z,8Z,11Z,14Z,17Z)-5,8,11,14,17-icosapentaenoic acid | |

| Identifiers | |

| 10417-94-4 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28364 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL460026 |

| ChemSpider | 393682 |

| DrugBank | DB00159 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.117.069 |

| 3362 | |

| UNII | AAN7QOV9EA |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C20H30O2 | |

| Molar mass | 302.451 g/mol |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

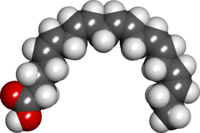

Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA; also icosapentaenoic acid) is an omega-3 fatty acid. In physiological literature, it is given the name 20:5(n-3). It also has the trivial name timnodonic acid. In chemical structure, EPA is a carboxylic acid with a 20-carbon chain and five cis double bonds; the first double bond is located at the third carbon from the omega end.

EPA is a polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) that acts as a precursor for prostaglandin-3 (which inhibits platelet aggregation), thromboxane-3, and leukotriene-5 eicosanoids. Studies of fish oil supplements, which contain EPA, have failed to support claims of preventing heart attacks or strokes.[1][2][3]

Sources

It is obtained in the human diet by eating oily fish or fish oil, e.g. cod liver, herring, mackerel, salmon, menhaden and sardine, and various types of edible seaweed and phytoplankton. It is also found in human breast milk.

However, fish can either synthesize EPA from fatty acids precursors found in their alimentation[4] or obtain it from the algae they consume.[5] It is available to humans from some non-animal sources (e.g. commercially, from microalgae, which are being developed as a commercial source).[6] EPA is not usually found in higher plants, but it has been reported in trace amounts in purslane.[7] In 2013, it was reported that a genetically modified form of the plant Camelina produced significant amounts of EPA.[8][9]

The human body converts alpha-linolenic acid (ALA) to EPA. ALA is itself an essential fatty acid, an appropriate supply of which must be ensured. The efficiency of the conversion of ALA to EPA, however, is much lower than the absorption of EPA from food containing it. Because EPA is also a precursor to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), ensuring a sufficient level of EPA on a diet containing neither EPA nor DHA is harder both because of the extra metabolic work required to synthesize EPA and because of the use of EPA to metabolize into DHA. Medical conditions like diabetes or certain allergies may significantly limit the human body's capacity for metabolization of EPA from ALA.

Clinical significance

The US National Institute of Health's MedlinePlus lists medical conditions for which EPA (alone or in concert with other ω-3 sources) is known or thought to be an effective treatment.[10] Most of these involve its ability to lower inflammation.

Intake of large doses (2.0 to 4.0 g/day) of long-chain omega-3 fatty acids as prescription drugs or dietary supplements are generally required to achieve significant (> 15%) lowering of triglycerides, and at those doses the effects can be significant (from 20% to 35% and even up to 45% in individuals with levels greater that 500 mg/dL). However, a far more effective method is to both greatly reduce, eliminate carbohydrate intake (and reduce stored body fats) because it is absorbed carbohydrates, converted to triglyceride fats for storage, which drive high triglyceride concentrations.[11]

It appears that both EPA and DHA lower triglycerides, however DHA appears to raise low-density lipoprotein (the variant which drives atherosclerosis; sometimes very inaccurately called: "bad cholesterol") and LDL-C values (always only a calculated estimate; not measured by labs from person's blood sample for technical and cost reasons), while EPA does not.

The big difference between in effect between dietary supplement and prescription forms of omega-3 fatty acids is that the prescription variants are concentrated to markedly increase the amount of these key fatty acids per capsule over the many other fats present in "fish oil" and the mercury, also present in "fish oil", has been removed.

EPA and DHA ethyl esters (all forms) may be absorbed less well, thus work less well, when taken on an empty stomach or with a low-fat meal.[12]

References

- ↑ Zimmer, Carl (September 17, 2015). "Inuit Study Adds Twist to Omega-3 Fatty Acids' Health Story". New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ↑ O'Connor, Anahad (March 30, 2015). "Fish Oil Claims Not Supported by Research". New York Times. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Grey, Andrew; Bolland, Mark (March 2014). "Clinical Trial Evidence and Use of Fish Oil Supplements". JAMA Internal Medicine. 174 (3): 460–462. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12765. Retrieved October 11, 2015.

- ↑ Committee on the Nutrient Requirements of Fish and Shrimp; National Research Council (2011). Nutrient requirements of fish and shrimp. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. ISBN 0-309-16338-2.

- ↑ Yvonne Bishop-Weston. "Plant based sources of vegan & vegetarian Docosahexaenoic acid – DHA and Eicosapentaenoic acid EPA & Essential Fats". Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- ↑ Jess Halliday (12 January 2007). "Water 4 to introduce algae DHA/EPA as food ingredient". Retrieved 2007-02-09.

- ↑ Simopoulos, Artemis P (2002). "Omega-3 fatty acids in wild plants, nuts and seeds" (PDF). Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 11 (Suppl 2): S163–73. doi:10.1046/j.1440-6047.11.s.6.5.x.

- ↑ Ruiz-Lopez, N.; Haslam, R. P.; Napier, J. A.; Sayanova, O. (January 2014). "Successful high-level accumulation of fish oil omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in a transgenic oilseed crop". The Plant Journal. 77 (2): 198–208. doi:10.1111/tpj.12378.

- ↑ Coghlan, Andy (4 January 2014) "Designed plant oozes vital fish oils"' New Scientist, volume 221, issue 2950, page 12, also available on the Internet at

- ↑ NIH Medline Plus. "MedlinePlus Herbs and Supplements: Omega-3 fatty acids, fish oil, alpha-linolenic acid". Archived from the original on February 8, 2006. Retrieved February 14, 2006.

- ↑ Jasmine Rana, KhanAcademy.org. "Introduction-to Energy Storage".

- ↑ Jacobson, T. A.; Maki, K. C.; Orringer, C. E.; Jones, P. H.; Kris-Etherton, P; Sikand, G; La Forge, R; Daniels, S. R.; Wilson, D. P.; Morris, P. B.; Wild, R. A.; Grundy, S. M.; Daviglus, M; Ferdinand, K. C.; Vijayaraghavan, K; Deedwania, P. C.; Aberg, J. A.; Liao, K. P.; McKenney, J. M.; Ross, J. L.; Braun, L. T.; Ito, M. K.; Bays, H. E.; Brown, W. V.; Nla Expert, Panel (2015). "National Lipid Association Recommendations for Patient-Centered Management of Dyslipidemia: Part 2". Journal of Clinical Lipidology. 9 (6 Suppl): S1–122.e1. doi:10.1016/j.jacl.2015.09.002. PMID 26699442.

External links

- EPA bound to proteins in the PDB