Treaty of Trianon

| Treaty of Peace between the Allied and Associated Powers and Hungary | |

|---|---|

|

Signing the Treaty on 4 June 1920 at the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles, arrival of the two signatories, Ágost Benárd and Alfréd Drasche-Lázár | |

| Signed | 4 June 1920 |

| Location | Versailles, France |

| Effective | 31 July 1921 |

| Signatories |

Hungary and Allied and Associated Powers

|

| Depositary | French Government |

| Languages | French, English, Italian |

|

| |

| Paris Peace Conference |

|---|

|

Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye |

|

Neuilly-sur-Seine |

|

Treaty of Trianon |

The Treaty of Trianon was the peace agreement of 1920 to formally end World War I between most of the Allies of World War I[1] and the Kingdom of Hungary, the latter being one of the successor states to Austria-Hungary.[2][3][4][5] The treaty regulated the status of an independent Hungarian state and defined its borders. It left Hungary as a landlocked state covering 93,073 square kilometres (35,936 sq mi), only 28% of the 325,411 square kilometres (125,642 sq mi) that had constituted the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary (the Hungarian half of the Austro-Hungarian monarchy). Its population was 7.6 million, only 36% of the pre-war kingdom's population of 20.9 million.[6] The areas that were allocated to neighbouring countries in total (and each of them separately) possessed a majority of non-Hungarian population, but 31% of Hungarians (3.3 million)[7] were left outside of post-Trianon Hungary.[8][9][10] Five of the pre-war kingdom's ten largest cities were drawn into other countries. The treaty limited Hungary's army to 35,000 officers and men, while the Austro-Hungarian Navy ceased to exist.

The principal beneficiaries of territorial division of pre-war Kingdom of Hungary were the Kingdom of Romania, the Czechoslovak Republic, and the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. One of the main elements of the treaty was the doctrine of "self-determination of peoples" and it was an attempt to give the non-Hungarians their own national states.[11] In addition, Hungary had to pay war reparations to its neighbours. The treaty was dictated by the Allies rather than negotiated and the Hungarians had no option but to accept its terms.[11] The Hungarian delegation signed the treaty under protest[8][12] on 4 June 1920 at the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles, France. The treaty was registered in League of Nations Treaty Series on 24 August 1921.[13]

The modern boundaries of Hungary are the same as those defined by the Treaty of Trianon except for three villages that were transferred to Czechoslovakia in 1947.

Borders of Hungary

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Hungary | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

|

Medieval

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Early modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Late modern

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Contemporary

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

By topic |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

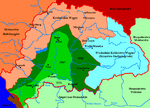

The Hungarian government terminated its union with Austria on 31 October 1918, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state. The de facto temporary borders of independent Hungary were defined by the ceasefire lines in November–December 1918. Compared with the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary, these temporary borders did not include:

- Part of Transylvania south of the Mureş (Maros) river and east of the Someş (Szamos) river, which came under the control of Romania (cease-fire agreement of Belgrade signed on 13 November 1918). On 1 December 1918, the National Assembly of Romanians in Transylvania declared union with the Kingdom of Romania.

- Slovakia, which became part of Czechoslovakia (status quo set by the Czechoslovak legions and accepted by the Entente on 25 November 1918). Afterwards the Slovak politician Milan Hodža discussed with the Hungarian Minister of Defence, Albert Bartha, a temporary demarcation line which had not followed the Slovak-Hungarian linguistic border, and left more than 900,000 Hungarians in the newly formed Czechoslovakia. That was signed on 6 December 1918.

- South Slavic lands, which, after the war, were organised into two political formations – the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs and Banat, Bačka and Baranja, which both came under control of South Slavs, according to the ceasefire agreement of Belgrade signed on 13 November 1918. Previously, on 29 October 1918, the Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia parliament, an autonomous kingdom within the Transleithania, terminated[14] the union[15] with the Kingdom of Hungary and on 30 October 1918 the Hungarian diet adopted a motion declaring that the constitutional relations between the two states have ended.[16] Croatia-Slavonia was included into a newly formed State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (which also included some other South Slavic territories, formerly administered by the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy) on 29 October 1918, which then was merged into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, formed by joining with the Kingdom of Serbia on 1 December 1918. Territories of Banat, Bačka and Baranja (which included most of the pre-war Baranya, Bács-Bodrog, Torontál, and Temes Counties) came under military control of the Kingdom of Serbia and political control of local South Slavs. The Great People's Assembly of Serbs, Bunjevci and other Slavs from Banat, Bačka and Baranja declared union of this region with the Kingdom of Serbia on 25 November 1918. The ceasefire line had a character of temporary international border until the treaty. Central parts of Banat were later assigned to Romania, respecting the wishes of Romanians from this area, which, on 1 December 1918, were present in the National Assembly of Romanians in Alba Iulia, which voted for union with the Kingdom of Romania.

- The city of Fiume (Rijeka) was occupied by the Italian Army. Its affiliation was a matter of international dispute between the Kingdom of Italy and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

- Croatian-populated territories in modern Međimurje remained under Hungarian control after the ceasefire agreement of Belgrade from 13 November 1918. After the military victory of Croatian forces led by Slavko Kvaternik in Međimurje against Hungarian forces, this region voted in the Great Assembly of 9 January 1919 for separation from Hungary [17] and entry into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

After the Romanian Army advanced beyond this cease-fire line, the Entente powers asked Hungary (Vix Note) to acknowledge the new Romanian territory gains by a new line set along the Tisza river. Unable to reject these terms and unwilling to accept them, the leaders of the Hungarian Democratic Republic resigned and the Communists seized power. In spite of the country being under Allied blockade, the Hungarian Soviet Republic was formed and the Hungarian Red Army was rapidly set up. This army was initially successful against the Czechoslovak Legions due to having been implicitly aided with food[18] and weapons by Italy;[19] which made it possible for Hungary to reach nearly the former Galitian (Polish) border, thus separating the Czechoslovak and Romanian troops from each other.

After a Hungarian-Czechoslovak cease-fire signed on 1 July 1919, the Hungarian Red Army left parts of Slovakia by 4 July, as the Entente powers promised to invite a Hungarian delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference. In the end, this particular invitation was not issued. Béla Kun, leader of the Hungarian Soviet Republic, then turned the Hungarian Red Army on the Romanian Army and attacked at the Tisza river on 20 July 1919. After fierce fighting that lasted some five days, the Hungarian Red Army collapsed. The Royal Romanian Army marched into Budapest on 4 August 1919.

The Hungarian state was restored by the Entente powers, helping Admiral Horthy into power in November 1919. On 1 December 1919 the Hungarian delegation was officially invited to the Versailles Peace Conference; however, the newly defined borders of Hungary were nearly concluded without the presence of the Hungarians.[20] During prior negotiations, the Hungarian party, along with the Austrian, advocated the American principle of self-determination: that the population of disputed territories should decide by free plebiscite to which country they wished to belong.[20][21] This view did not prevail for long, as it was disregarded by the decisive French and British delegates.[22] According to some opinions, the Allies drafted the outline of the new frontiers [23] with little or no regard to the historical, cultural, ethnic, geographic, economic and strategic aspects of the region.[20][23][24] The Allies assigned territories that were mostly populated by non-Hungarian ethnicities to successor states, but also allowed these states to absorb sizeable territories that were mainly inhabited by Hungarian-speaking populations. For instance, Romania gained all of Transylvania, which was home to 2,800,000 Romanians, but also contained a significant minority of 1,600,000 Magyars and about 250,000 Germans.[25] The intent of the Allies was principally to strengthen these successor states at the expense of Hungary. Although the countries that were the main beneficiaries of the treaty partially noted the issues, the Hungarian delegates tried to draw attention to them. Their views were disregarded by the Allied representatives.

Some predominantly Hungarian settlements, consisting of more than 2 million people, were situated in a typically 20–50 km (12–31 mi) wide strip along the new borders in foreign territory. More concentrated groups were found in Czechoslovakia (parts of southern Slovakia), SCS Kingdom (parts of northern Vojvodina), and Romania (parts of Transylvania).

The final borders of Hungary were defined by the Treaty of Trianon signed on 4 June 1920. Beside exclusion of the previously mentioned territories, they did not include:

- the rest of Transylvania, which together with some additional parts of pre-war Kingdom of Hungary became part of Romania;

- Carpathian Ruthenia, which became part of Czechoslovakia, pursuant to the Treaty of Saint-Germain in 1919;

- most of Burgenland, which became part of Austria, also pursuant to the Treaty of Saint-Germain; the district of Sopron opted to remain within Hungary after a plebiscite held in December 1921 (it was the only place where a plebiscite was held and factored in the decision); and

- Međimurje and the 2/3 of the Slovene March or Vendvidék (now Prekmurje), which became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.

By the Treaty of Trianon, the cities of Pécs, Mohács, Baja and Szigetvár, which were under Serb-Croat-Slovene administration after November 1918, were assigned to Hungary. An arbitration committee in 1920 assigned small northern parts of the former Árva and Szepes counties of the Kingdom of Hungary with Polish majority population to Poland. After 1918, Hungary did not have access to the sea, which pre-war Kingdom of Hungary formerly had directly through the Rijeka coastline and indirectly through Croatia-Slavonia.

With the help of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, Hungary expanded its borders towards neighbouring countries at the outset of World War II. This started under the Munich Agreement (1938), then the two Vienna Awards (1938 and 1940), and was continued with the dissolution of Czechoslovakia (occupation of northern Carpathian Ruthenia and eastern Slovakia) and the Axis invasion of Yugoslavia. This territorial expansion was short-lived, since the post-war Hungarian boundaries agreed on at the Treaty of Paris in 1947 were nearly identical to those of 1920 (with three villages – Jarovce, Rusovce, and Čunovo – transferred to Czechoslovakia).

Representatives of small nations living in the former Austria-Hungary and active in the Congress of Oppressed Nations regarded the treaty of Trianon for being an act of historical righteousness[26] because a better future for their nations was "to be founded and durably assured on the firm basis of world democracy, real and sovereign government by the people, and a universal alliance of the nations vested with the authority of arbitration" while at the same time making a call for putting an end to "the existing unbearable domination of one nation over the other" and making it possible "for nations to organize their relations to each other on the basis of equal rights and free conventions". Furthermore, they believed the treaty would help toward a new era of dependence on international law, the fraternity of nations, equal rights, and human liberty as well as aid civilisation in the effort to free humanity from international violence.[27]

Results and consequences of the Treaty

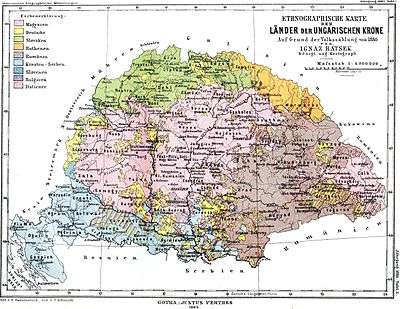

The 1910 census

The last census before the Treaty of Trianon was held in 1910. This census recorded population by language and religion, but not by ethnicity. However, it is generally accepted that the largest ethnic group in the Kingdom of Hungary in this time were the Hungarians. According to the 1910 census, speakers of the Hungarian language included approximately 48% of the entire population of the kingdom, and 54% of the population of the territory referred to as "Hungary proper", i.e. excluding Croatia-Slavonia. Within the borders of "Hungary proper" numerous ethnic minorities were present: 16.1% Romanians, 10.5% Slovaks, 10.4% Germans, 2.5% Ruthenians, 2.5% Serbs and 8% others.[31] 5% of the population of "Hungary proper" were Jews, who were included in speakers of the Hungarian language.[32] The population of the autonomous Croatia-Slavonia was mostly composed of Croats and Serbs (who together counted 87% of population).

Criticism of the 1910 census

The census of 1910 classified the residents of the Kingdom of Hungary by their native languages[33] and religions, so it presents the preferred language of the individual, which may or may not correspond to the individual's ethnic identity. To make the situation even more complex, in the multilingual kingdom there were territories with ethnically mixed populations where people spoke two or even three languages natively. For example, in Slovakia 18% of the Slovaks, 33% of the Hungarians and 65% of the Germans were bilingual. In addition, 21% of the Germans in the region spoke both Slovak and Hungarian beside German.[34] These reasons are ground for debate about the accuracy of the census.

While several demographers (David W. Paul,[35] Peter Hanak, László Katus[36]) state that the outcome of the census is reasonably accurate (assuming that it is also properly interpreted), others believe that the 1910 census was manipulated[37][38] by exaggerating the percentage of the speakers of Hungarian, pointing to the discrepancy between an improbably high growth of the Hungarian-speaking population and the decrease of percentual participation of speakers of other languages due to Magyarization in the kingdom in the late 19th century.[39]

Some Slovak demographers (such as Ján Svetoň and Julius Mesaros) dispute the result of every pre-war census.[35] Owen Johnson, an American historian, accepts the numbers of the earlier censuses up to the one in 1900, according to which the proportion of the Hungarians was 51.4%,[31] but he neglects the 1910 census as he thinks the changes since the last census are too big.[35] It is also argued that there were different results in previous censuses in the Kingdom of Hungary and subsequent censuses in the new states. Considering the size of discrepancies, some demographers are on the opinion that these censuses were somewhat biased in the favour of the respective ruling nation.[40]

Distribution of the non-Hungarian and Hungarian populations

The number of non-Hungarian and Hungarian communities in the different areas based on the census data of 1910 (in this, people were not directly asked about their ethnicity, but about their native language). The present day location of each area is given in parenthesis.

| |

|

|

|

| Transylvania (Romania) | Romanian – 2,819,467 (54%) | 1,658,045 (31.7%) | German – 550,964 (10.5%) |

| Slovakia | Slovak – 1,688,413 (57.9%) | 881,320 (30.2%) | German – 198,405 (6.8%) |

| Vojvodina (Serbia) | Serbo-Croatian – 601,770 (39.8%) * Serbian – 510,754 (33.8%) * Croatian, Bunjevac and Šokac – 91,016 (6%) |

425,672 (28.1%) | German – 324,017 (21.4%) |

| Transcarpathia (Ukraine) | Ruthenian or Ukrainian – 330,010 (54.5%) | 185,433 (30.6%) | German – 64,257 (10.6%) |

| Croatia | Croatian - 1,638,350 (62.3%) | 121,000 (3.5%) | Serbian - 644,955 (24.6%) German – 134,078 (5.1%) |

| Fiume (Croatia) | Italian – 24,212 (48.6%) | 6,493 (13%) | Croatian and Serbian – 13,351 (26.8%) Slovene - 2,336 (4.7%) German - 2,315 (4.6%) |

| Burgenland (Austria) | German – 217,072 (74.4%) | 26,225 (9%) | Croatian – 43,633 (15%) |

| Prekmurje (Slovenia) | Slovene – 74,199 (80.4%) – in 1921 | 14,065 (15.2%) – in 1921 | German – 2,540 (2.8%) – in 1921 |

According to another source, population distribution in 1910 looked as follows:

| |

|

|

| Transylvania (Romania) | 2,831,222 Romanians (53.8%). The 1919 and 1920 Transylvanian censuses indicate a greater percentage of Romanians (57.1% / 57.3%)[41] | 2,431,273 "others" (mostly Hungarians – 1,662,948 (31.6%) and Germans – 563,087 (10.7%)). The 1919 and 1920 Transylvanian censuses indicate a smaller Hungarian minority (26.5% / 25.5%).[41] |

| Slovakia (Czechoslovakia) | 1,687,977 Slovaks [according to the 1921 census: 1,941,942 Slovaks] | 1,233,454 "others" (mostly Hungarians – 886,044, Germans, Ruthenians and Roma) [according to the 1921 census: 1,058,928 of "others"] |

| Croatia-Slavonia, Vojvodina, Međimurje, Prekmurje (SCS Kingdom) | 2,756,000 Croats and Serbs | 1,366,000 others (mostly Hungarians and Germans) |

| Carpathian Ruthenia (Czechoslovakia) | 330,010 Ruthenians | 275,932 "others" (mostly Hungarians, Germans, Romanians, and Slovaks) |

| Burgenland (Austria) | 217,072 Germans | 69,858 "others" (mainly Croatian and Hungarian) |

Hungarians outside the newly defined borders

The territories of the former Hungarian Kingdom that were ceded by the treaty to neighbouring countries in total (and each of them separately) had a majority of non-Hungarian nationals, however the Hungarian ethnic area was much larger than the newly established territory of Hungary,[42] therefore 30 percent of the ethnic Hungarians were under foreign authority.[43]

After the treaty, the percentage and the absolute number of all Hungarian populations outside of Hungary decreased in the next decades (although, some of these populations also recorded temporary increase of the absolute population number). There are several reasons for this population decrease, some of which were spontaneous assimilation and certain state policies, like Slovakization, Romanianization, Serbianisation. Other important factors were the Hungarian migration from the neighbouring states to Hungary or to some western countries as well as decreased birth rate of Hungarian populations. According to the National Office for Refugees, the number of Hungarians who immigrated to Hungary from neighbouring countries was about 350,000 between 1918 and 1924.[44]

Minorities in post-Trianon Hungary

On the other hand, a considerable number of other nationalities remained within the frontiers of the independent Hungary:

According to the 1920 census 10.4% of the population spoke one of the minority languages as mother language:

- 551,212 German (6.9%)

- 141,882 Slovak (1.8%)

- 36,858 Croatian (0.5%)

- 23,760 Romanian (0.3%)

- 23,228 Bunjevac and Šokac (0.3%)

- 17,131 Serbian (0.2%)

- 7,000 Slovene (0.08%)

The percentage and the absolute number of all non-Hungarian nationalities decreased in the next decades, although the total population of the country increased. Bilingualism was also disappearing. The main reasons of this process were both spontaneous assimilation and the deliberate Magyarization policy of the state. Minorities made up 8% of the total population in 1930 and 7% in 1941 (on the post-Trianon territory).

After World War II approximately 200,000 Germans were deported to Germany, according to the decree of the Potsdam Conference. Under the forced exchange of population between Czechoslovakia and Hungary, approximately 73,000 Slovaks left Hungary and according to different estimations 120,500[45][46] or 45,000[47] Hungarians moved to present day Hungarian territory from Czechoslovakia. After these population movements Hungary became an almost ethnically homogeneous country with the exception of the Hungarian speaking Romani people.

Political consequences

Officially the treaty was intended to be a confirmation of the right of self-determination for nations and of the concept of nation-states replacing the old multinational Austro-Hungarian empire. Although the treaty addressed some nationality issues, it also sparked some new ones.

The minority ethnic groups of the pre-war kingdom were the major beneficiaries. The Allies had explicitly committed themselves to the causes of the minority peoples of Austria-Hungary late in World War I. For all intents and purposes, the death knell of the Austro-Hungarian empire sounded on 14 October 1918, when United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing informed Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister István Burián that autonomy for the nationalities was no longer enough. Accordingly, the Allies assumed without question that the minority ethnic groups of the pre-war kingdom wanted to leave Hungary. The Romanians joined their ethnic brethren in Romania, while the Slovaks, Serbs and Croats helped establish nation-states of their own (Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia). However, these new or enlarged countries also absorbed large slices of territory with a majority of ethnic Hungarians or Hungarian speaking population. As a result, as many as a third of Hungarian language-speakers found themselves outside the borders of the post-Trianon Hungary.

While the territories that were now outside Hungary's borders had non-Hungarian majorities overall, there also existed some sizeable areas with a majority of Hungarians, largely near the newly defined borders. Over the last century, concerns have occasionally been raised about the treatment of these ethnic Hungarian communities in the neighbouring states.[48][49][50] Areas with significant Hungarian populations included the Székely Land[51] in Eastern Transylvania, the area along the newly defined Romanian-Hungarian border (cities of Arad, Oradea), the area north of the newly defined Czechoslovakian–Hungarian border (Komárno, Csallóköz), southern parts of Subcarpathia and northern parts of Vojvodina.

The Allies rejected the idea of plebiscites in the disputed areas with the exception of the city of Sopron, which voted in favour of Hungary. The Allies were indifferent as to the exact line of the newly defined border between Austria and Hungary. Furthermore, ethnically diverse Transylvania, with an overall Romanian majority (53.8% – 1910 census data or 57.1% – 1919 census data or 57.3% – 1920 census data), was treated as a single entity at the peace negotiations and was assigned in its entirety to Romania. The option of partition along ethnic lines as an alternative was rejected.

Another reason why the victorious Allies decided to dissolve the Central-European great power, Austria-Hungary, a strong German supporter and fast developing region, was to prevent Germany from acquiring substantial influence in the future.[52] The Western powers' main priority was to prevent a resurgence of the German Reich and they therefore decided that her allies in the region, Austria and Hungary, should be "contained" by a ring of states friendly to the Allies, each of which would be bigger than either Austria or Hungary.[53] Compared to the Habsburg Kingdom of Hungary, post-Trianon Hungary had 60% less population and its political and economic footprint in the region was significantly reduced. Hungary lost connection to strategic military and economic infrastructure due to the concentric layout of the railway and road network which the borders bisected. In addition, the structure of its economy collapsed, because it had relied on other parts of the pre-war Kingdom. The country also lost access to the Mediterranean and to the important sea port of Rijeka (Fiume), and became landlocked, which had a negative effect on sea trading and strategic naval operations. Furthermore, many trading routes that went through the newly defined borders from various parts of the pre-war kingdom were abandoned.

With regard to the ethnic issues, the Western powers were aware of the problem posed by the presence of so many Hungarians (and Germans) living outside the new nation-states of Hungary and Austria. The Romanian delegation to Versailles feared in 1919 that the Allies were beginning to favour the partition of Transylvania along ethnic lines to reduce the potential exodus and Prime Minister Ion I. C. Brătianu even summoned British-born Queen Marie to France to strengthen their case. The Romanians had suffered a higher relative casualty rate in the war than either Britain[54][55][56] or France[55][56][57] so it was considered that the Western powers had a moral debt to repay. In absolute terms, Romanian troops had considerably fewer casualties than either Britain or France, however.[56] The underlying reason for the decision was a secret pact between The Entente and Romania.[58] In the Treaty of Bucharest (1916) Romania was promised Transylvania and territories to the east of river Tisza, provided that she attacked Austria-Hungary from the south-east, where defences were weak. However, after the Central Powers had noticed the military manoeuvre, the attempt was quickly choked off and Bucharest fell in the same year.

By the time the victorious Allies arrived in France, the treaty was already settled, which made the outcome inevitable. At the heart of the dispute lay fundamentally different views on the nature of the Hungarian presence in the disputed territories. For Hungarians, the outer territories were not seen as colonial territories, but rather part of the core national territory.[59] The western powers and most non-Hungarians that lived in the Pannonian Basin saw the Hungarians as colonial-style rulers who had oppressed the Slavs and Romanians since 1848, when they introduced laws that the language used in education and in local offices was to be Hungarian.[60] For non-Hungarians from the Pannonian Basin it was a process of decolonisation instead of a punitive dismemberment (as was seen by the Hungarians).[61] The Hungarians did not see it this way because the newly defined borders did not fully respect territorial distribution of ethnic groups,[62] with areas where there were Hungarian majorities[62] outside the new borders. The French sided with their allies the Romanians who had a long policy of cultural ties to France since the country broke from the Ottoman Empire (due in part to the relative ease at which Romanians could learn French)[63] although Clemenceau personally detested Bratianu.[61] President Wilson initially supported the outline of a border that would have more respect to ethnic distribution of population based on the Coolidge Report, led by A. C. Coolidge, a Harvard professor, but later gave in, due to changing international politics and as a courtesy to other allies.[64]

For Hungarian public opinion, the fact that almost three-fourths of the pre-war kingdom's territory and a significant number of ethnic Hungarians were assigned to neighbouring countries triggered considerable bitterness. Most Hungarians preferred to maintain the territorial integrity of the pre-war kingdom. The Hungarian politicians claimed that they were ready to give the non-Hungarian ethnicities a great deal of autonomy.[65] Most Hungarians regarded the treaty as an insult to the nation's honour. The Hungarian political attitude towards Trianon was summed up in the phrases Nem, nem, soha! ("No, no, never!") and Mindent vissza! ("Return everything!" or "Everything back!").[66] The perceived humiliation of the treaty became a dominant theme in inter-war Hungarian politics, analogous with the German reaction to the Treaty of Versailles. The outcome of the Treaty of Trianon is to this day remembered in Hungary as the Trianon trauma.[51] All official flags in Hungary were lowered until 1938, when they were raised by one-third[67] after southern Slovakia and Ruthenia, with an 59% resp. 86% Hungarian population (according to Czechoslovak and later Hungarian cenzus) was "recovered" following the Munich Conference and Vienna Awards by which arbiters of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy sought to enforce peacefully the claims of Hungary on territories of the pre-war Kingdom of Hungary that were not assigned to Hungary in 1920 when it signed the Treaty of Trianon. The Hungarian irredentism fuelled not only the post-war kingdom's revisionist foreign policy[59] but became a source of regional tension after the Cold War too.[59]

Economic consequences

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was one economic unit with autarkic characteristics[68][69] during its golden age and therefore achieved rapid growth, especially in the early 20th century when GNP grew by 1.76%.[70] (That level of growth compared very favourably to that of other European nations such as Britain (1.00%), France (1.06%), and Germany (1.51%).) There was also a division of labour present throughout the empire: that is, in the Austrian part of the Monarchy manufacturing industries were highly advanced, while in the Kingdom of Hungary an agroindustrial economy had emerged. By the late 19th century, economic growth of the eastern regions consistently surpassed that of western, thus discrepancies eventually began to diminish. The key success of fast development was specialisation of each region in fields that they were best.

The Kingdom of Hungary was the main supplier of wheat, rye, barley and other various goods in the empire and these comprised a large portion of the empire's exports.[71] Meanwhile, the territory of present-day Czech Republic (Kingdom of Bohemia) owned 75% of the whole industrial capacity of former Austria-Hungary.[72] This shows that the various parts of the former monarchy were economically interdependent. As a further illustration of this issue, post-Trianon Hungary produced 500% more agricultural goods than it needed for itself[73] and mills around Budapest (some of the largest ones in Europe at the time) operated at 20% level. As a consequence of the treaty, all the competitive industries of the former empire were compelled to close doors, as great capacity was met by negligible demand owing to economic barriers presented in the form of the newly defined borders.

Post-Trianon Hungary possessed 90% of the engineering and printing industry of the pre-war Kingdom, while only 11% of timber and 16% of iron was retained. In addition, 61% of arable land, 74% of public roads, 65% of canals, 62% of railroads, 64% of hard surface roads, 83% of pig iron output, 55% of industrial plants, and 67% of credit and banking institutions of the former Kingdom of Hungary lay within the territory of Hungary's neighbours.[74][75][76] New borders also bisected transport links – in the Kingdom of Hungary the road and railway network had a radial structure, with Budapest in the centre. Many roads and railways, running along the newly defined borders and interlinking radial transport lines, ended up in different, highly introvert countries. Hence, much of the rail cargo traffic of the emergent states was virtually paralysed.[77] These factors all combined created some imbalances in the now separated economic regions of the former Monarchy.

.jpg)

The disseminating economic problems had been also noted in the Coolidge Report as a serious potential aftermath of the treaty.[22] This opinion was not taken into account during the negotiations. Thus, the resulting uneasiness and despondency of one part of the concerned population was later one of the main antecedents of World War II. Unemployment levels in Austria, as well as in Hungary, were dangerously high, and industrial output dropped by 65%. What happened to Austria in industry happened to Hungary in agriculture where production of grain declined by more than 70%.[78] Austria, especially the imperial capital Vienna, was a leading investor of development projects throughout the empire with more than 2.2 billion crown capital. This sum sunk to a mere 8.6 million crowns after the treaty took effect and resulted in a starving of capital in other regions of the former empire.[79]

The disintegration of the multi-national state conversely impacted neighbouring countries, too: In Poland, Romania, Yugoslavia, and Bulgaria a fifth to a third of the rural population could find no work, and industry was in no position to absorb them.

In comparison, by 1921 the new Czechoslovak state reached 75% of its pre-war production owing to their favourable position among the victors, and greater associated access to international rehabilitation resources.[80]

With the creation of customs barriers and fragmented protective economies, the economic growth and outlook in the region sharply declined,[81] ultimately culminating in a deep recession. It proved to be immensely challenging for the successor states to successfully transform their economies to adapt to the new circumstances. All the formal districts of Austria-Hungary used to rely on each other's exports for growth and welfare; by contrast, 5 years after the treaty, traffic of goods between the countries dropped to less than 5% of its former value. This could be attributed to the introduction of aggressive nationalistic policies by local political leaders.[82]

The drastic shift in economic climate forced the countries to re-evaluate their situation and to promote industries where they had fallen short. Austria and Czechoslovakia subsidised the mill, sugar and brewing industries, while Hungary attempted to increase the efficiency of iron, steel, glass and chemical industries.[68][83] The stated objective was that all countries should become self-sufficient. This tendency, however, led to uniform economies and competitive economic advantage of long well-established industries and research fields evaporated. The lack of specialisation adversely affected the whole Danube-Carpathian region and caused a distinct setback of growth and development compared to the West as well as high financial vulnerability and instability.[84][85]

Miscellaneous consequences

Romania, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia had to assume part of the financial obligations of the former Kingdom of Hungary on account of the parts of its former territory that were assigned under their sovereignty.

Some conditions of the Treaty were similar to those imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles. After the war, the Austro-Hungarian navy, air force and army were disbanded. The army of post-Trianon Hungary was to be restricted to 35,000 men and there was to be no conscription. Heavy artillery, tanks and air force were prohibited.[76] Further provisions stated that in Hungary, no railway would be built with more than one track, because at that time railways held substantial strategic importance economically and militarily.[86]

Hungary also renounced all privileges in territories outside Europe that were administered by the former Austro-Hungarian monarchy.

Articles 54–60 of the Treaty required Hungary to recognise various rights of national minorities within its borders.[87]

Articles 61–66 stated that all former citizens of the Kingdom of Hungary living outside the newly defined frontiers of Hungary were to ipso facto lose their Hungarian nationality in one year.[88]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The U.S. ended the war with the U.S.–Hungarian Peace Treaty (1921)

- ↑ Craig, G. A. (1966). Europe since 1914. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- ↑ Grenville, J. A. S. (1974). The Major International Treaties 1914–1973. A history and guides with texts. Methnen London.

- ↑ Lichtheim, G. (1974). Europe in the Twentieth Century. New York: Praeger.

- ↑ "Text of the Treaty, Treaty of Peace Between The Allied and Associated Powers and Hungary And Protocol and Declaration, Signed at Trianon June 4, 1920". Retrieved 10 June 2009.

- ↑ "Open-Site:Hungary".

- ↑ Richard C. Frucht (31 December 2004). Eastern Europe: An Introduction to the People, Lands, and Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 360. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

- 1 2 "Trianon, Treaty of". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2009.

- ↑ Macartney, C. A. (1937). Hungary and her successors: The Treaty of Trianon and Its Consequences 1919–1937. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Bernstein, Richard (9 August 2003). "East on the Danube: Hungary's Tragic Century". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 March 2008.

- 1 2 Martin P. van den Heuvel,Jan Geert Siccama: The Disintegration of Yugoslavia, Yearbook of European Studies, 1992

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer; Priscilla Mary Roberts (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I (1 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 1183. ISBN 978-1-85109-420-2.

Virtually the entire population of what remained of Hungary regarded the Treaty of Trianon as manifestly unfair, and agitation for revision began immediately.

- ↑ League of Nations Treaty Series, vol. 6, p. 188.

- ↑ "Povijest saborovanja" [History of parliamentarism] (in Croatian). Sabor. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "Constitution of Union between Croatia-Slavonia and Hungary". H-net.org. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Wide anarchy in Austria". New York Times. 1 November 1918. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Hrvatski sabor". Sabor.hr. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ "Die Ereignisse in der Slovakei," Der Demokrat (morning edition), 4 June 1919.

- ↑ Die italienisch-ungarische Freundschaft," Bohemia, 29 June 1919.

- 1 2 3 Arno J. Mayer, Politics and Diplomacy of Peacemaking. Containment and Counterrevolution at Versailles, 1918–1919 (New York, 1967), p. 369

- ↑ David Hunter Miller, XVIII, 496.

- 1 2 Francis Deak, Hungary at the Paris Peace Conference. The Diplomatic History of the Treaty of Trianon (New York: Columbia University Press, 1942), p. 45.

- 1 2 Miller, Vol. IV, 209. Document 246. "Outline of Tentative Report and Recommendations Prepared by the Intelligence Section, in Accordance with Instructions, for the President and the Plenipotentiaries 21 January 1919."

- ↑ Miller. IV. 234., 245.

- ↑ Történelmi világatlasz [World Atlas of History] (in Hungarian). Cartographia. 1998. ISBN 963-352-519-5.

- ↑ Michálek, Slavomír (1999). Diplomat Štefan Osuský (in Slovak). Bratislava: Veda. ISBN 80-224-0565-5.

- ↑ "Prague Congress of Oppressed nations, Details that Austrian censor suppressed –Text of revolutionary proclamation,". The New York Times. 23 August 1918. Retrieved 22 May 2011.

- ↑ "Teleki Pál – egy ellentmondásos életút" (in Hungarian). National Geographic Hungary. 18 February 2004. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ↑ "A kartográfia története" (in Hungarian). Babits Publishing Company. Retrieved 30 January 2008.

- ↑ Spatiul istoric si etnic romanesc, Editura Militara, Bucuresti, 1992

- 1 2 Frucht, p. 356.

- ↑ A. J. P. Taylor, The Habsburg Monarchy 1809–1918, 1948.

- ↑ Károly Kocsis, Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi: Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin, EXEN, 1998

- ↑ Kocsis & Kocsis-Hodosi, p. 57.

- 1 2 3 Brass, p. 156.

- ↑ Brass, p. 132.

- ↑ Teich, Mikuláš; Dušan Kováč; Martin D. Brown (3 February 2011). Slovakia in History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80253-6. Retrieved 15 September 2011.

- ↑ Murad, Anatol (1968). Franz Joseph I of Austria and his Empire. New York: Twayne Publishers. p. 20. Retrieved 30 November 2011.

- ↑ Seton-Watson, Robert William (1933). "The Problem of Treaty Revision and the Hungarian Frontiers". International Affairs. 12 (4): 481–503. doi:10.2307/2603603.

- ↑ Kirk, Dudley (1 January 1969). Europe's Population in the Interwar Years. New York: Gordon and Bleach, Science Publishers. p. 226. ISBN 0-677-01560-7.

- 1 2 Árpád Varga. "Hungarians in Transylvania between 1870 and 1995".

- ↑ Piotr Eberhardt, Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, and Analysis, M.E. Sharpe, 2003, pp. 290–299

- ↑ Uri Ra'anan, State and Nation in Multi-Ethnic Societies: The Breakup of Multinational States, Manchester University Press, 1991, p. 106

- ↑ Kocsis & Kocsis-Hodosi, p. 19.

- ↑ Károly Kocsis; Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi (1 December 1998). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minority on the Carpathian Basin. Simon Publications LLC. p. 23. ISBN 978-1-931313-75-9.

- ↑ Gustavo Corni; Tamás Stark (15 September 2008). Peoples on the Move: Population Transfers and Ethnic Cleansing Policies during World War II and its Aftermath. Berg. p. 83. ISBN 978-1-84520-480-8.

- ↑ Prof. PaedDr. Štefan Šutaj, DrSc. (2007). "The Czechoslovak government policy and population exchange (A csehszlovák kormánypolitika és a lakosságcsere)". Slovak Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ↑ "Assaults on Minorities in Vojvodina". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ↑ "Official Letter from Tom Lantos to Robert Fico" (PDF). Congress of the United States, Committee on Foreign affairs. 17 October 2007. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- ↑ "U.S. lawmaker blames Slovak government for ethnically motivated attacks on Hungarians". International Herald Tribune. 5 September 2006. Retrieved 15 April 2008.

- 1 2 Kulish, Nicholas (7 April 2008). "Kosovo's Actions Hearten a Hungarian Enclave". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste Duroselle, From Wilson to Roosevelt

- ↑ Macmillan, Margaret (2003). Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World. Random House.

- ↑ "Britain census 1911". Genealogy.about.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- 1 2 Present Day Romania census 1912 – population of Transylvania

- 1 2 3 "World War I casualties". Kilidavid.com. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Clarey, Christopher. "France census 1911". International Herald Tribune. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Wilfried Fest, Peace or Partition, The Habsburg Monarchy and British Policy, 1914–1918 (New York: St. Martin's 1978). p.37

- 1 2 3 White, George W. (2000). Nationalism and Territory: Constructing Group Identity in Southeastern Europe. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 67–109. ISBN 978-0-8476-9809-7.

- ↑ Száray, Miklós. (2006). Történelem III. Műszaki Kiadó. p. 132.

- 1 2 Julia P. Gelardi (2006). Born to rule: granddaughters of Victoria, queens of Europe : Maud of Norway, Sophie of Greece, Alexandra of Russia, Marie of Romania, Victoria Eugenie of Spain. ISBN 978-0-7553-1392-1.

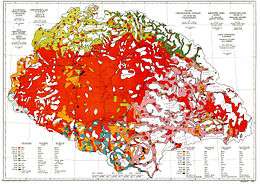

- 1 2 Ethnic map of Kingdom of Hungary without Croatia-Slavonia

- ↑ Variously mentioned throughout Glenny, Misha. The Balkans

- ↑ Laurence Emerson Gelfand, The Inquiry; American Preparation for Peace, 1917–1919 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1963), p. 332.

- ↑ Coolidge, 20.

- ↑ Dent, Peter. Trianon tribulations. Budapest Times, 26 May 2010.

- ↑ Miller, 231.

- 1 2 "Britannica 1911: Hungary/Commerce". 1911encyclopedia.org. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ Vide for the controversy of the role of the state: Iván T. Berend and Gy. Ranki, "Az allam szerepe az europai 'periferia' XIX. szazadi gazdasagi fejlodesben." The Role of the State in the 19th Century Economic Development of the European "periphery." Valosag 21, no.3 (Budapest, 1978), pp. 1–11; L. Lengyel, "Kolcsonos tarsadalmi fuggoseg a XIX szazadi europai gazdasagi fejlodesben." (Socio-Economic Interdependence in the European Economic Development of the 19th Century.) Valosag 21, no.9 (Budapest, 1978), pp. 100–106

- ↑ Good, David. The Economic Rise of the Habsburg Empire

- ↑ Gonnard, La Hongrie, p. 72.

- ↑ Alice Teichova, An Economic Background to Munich International Business and Czechoslovakia 1918–1938 (Cambridge, 1978); R. Olsovsky, V. Prucha, et al., Prehled gospodursveho vyvoje Ceskoslovehska v letech 1918–1945 [Survey of the economic development of Czechoslovakia] (Prague, 1961).

- ↑ Iván T. Berend and Gyorgy Ranki, Magyarorszag gazdasaga 1919–1929 [Hungary's economy] (Budapest, 1965).

- ↑ Flood-light on Europe: a guide to the next war By Felix Wittmer Published by C. Scribner's sons, 1937 Item notes: pt. 443 Original from Indiana University Digitized 13 November 2008 p. 114

- ↑ History of the Hungarian Nation By Domokos G. Kosáry, Steven Béla Várdy, Danubian Research Center Published by Danubian Press, 1969 Original from the University of California Digitized 19 June 2008 p. 222

- 1 2 Spencer C. Tucker; Laura M. Wood (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Garland Pub. p. 698. ISBN 978-0-8153-0399-2.

- ↑ Deak, 436.

- ↑ G. Gratz and R. Schuller, Die Wirtschaftliche Zusammenbruch Oesterreich Ungarns (Vienna. 1930); K. Rotschild, Austria's Economic Development Between the Two Wars (London, 1946).

- ↑ N. Layton and Ch. Rist, The Economic Situation of Austria (Geneva, 1923).

- ↑ T. Faltus, Povojnova hospodarska kriza v rokoch 1912–1923 v Ceskoslovensku [Postwar Depression in Czechoslovakia] (Bratislava, 1966).

- ↑ Deak 16.

- ↑ A. Basch, European Economic Nationalism (Washington, 1943); L. Pasvolsky, Economic Nationalism of the Danubian States (New York, 1929).

- ↑ "Britannica 1911:Bohemia/Manufactures and Commerce". 1911encyclopedia.org. 27 October 2006. Retrieved 4 June 2013.

- ↑ I. Svennilson, Growth and Stagnation in the European Economy (Geneva, 1954)

- ↑ Iván T. Berend and G. Ranki, Economic Development of East Central Europe (New York, 1974).

- ↑ By Edwin A. Pratt, The Rise of Rail-Power in War and Conquest

- ↑ Wikisource: Protection of minorities

- ↑ Wikisource: Nationality

References

- Károly Kocsis; Eszter Kocsisné Hodosi (1998). Ethnic Geography of the Hungarian Minorities in the Carpathian Basin. ISBN 978-963-7395-84-0.

- Piotr Eberhardt (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-Century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M E Sharpe Inc. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- Paul R. Brass (1985). Ethnic Groups and the State. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7099-3272-7.

- Eastern Europe. 2005. ISBN 978-1-57607-800-6.

Further reading

- Dupcsik, Csaba; Repárszky, Ildikó (2001). Történelem IV. XX. század (in Hungarian). Budapest: Műszaki Könyvkiadó. ISBN 978-963-16-2814-2.

- Effects of the Treaty on the geo-politics of Hungary and the successor states

- Ernest A. Rockwell: Trianon Politics, 1994–1995, thesis, Central Missouri State University, 1995.

- Minorities in post-Trianon Hungary literature

- József Kovacsics: Magyarország történeti demográfiája : Magyarország népessége a honfoglalástól 1949-ig, Budapest : Közgazd. és Jogi Kiadó ; 1963 Budapest Kossuth Ny.

- Lajos Thirring: Az 1869–1980. évi népszámlálások története és jellemzői [kész. a Központi Statisztikai Hivatal Népesedésstatisztikai Főosztályán], Bp. : SKV, 1983

- Events preceding the Treaty and for minorities in the post-Trianon successor states

- Ernő Raffay: Magyar tragédia: Trianon 75 éve. Püski kiadó (1996)

- Vitéz Károly Kollányi: Kárpáti trilógia. Kráter Műhely Egyesület (2002)

- Macartney, Carlile Aylmer October Fifteenth – A History of Modern Hungary 1929–1945. Edinburgh University Press (1956)

- Juhász Gyula: Magyarország Külpolitikája 1919–1945. Kossuth Könyvkiado, Budapest (1969).

- General H.H. Bandholtz: "An Undiplomatic Diary". Columbia University (1933)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Treaty of Trianon. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Hungarian Government Office for Hungarians Abroad

- Map of Hungarian borders in November–December 1918

- Map of Europe and Treaty of Trianon at omniatlas.com

.jpg)