Austro-Hungarian Navy

| Austro-Hungarian Navy kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine Császári és Királyi Haditengerészet | |

|---|---|

|

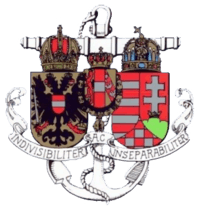

Coat of arms of the Austro-Hungarian Navy | |

| Active | 1786–1918 |

| Country |

|

| Branch | Navy |

| Role | Defence of the Adriatic Sea |

| Size |

4 Dreadnoughts 9 Pre-dreadnoughts 4 Coastal defence ships 3 Armoured cruisers 6 Light cruisers 30 Destroyers 36 Torpedo boats 6 Submarines |

| Engagements |

Seven Weeks War Boxer Rebellion World War I |

| Commanders | |

| Notable commanders |

Wilhelm von Tegetthoff Anton Haus Miklós Horthy |

| Insignia | |

| Naval ensign 1915–18 |

.svg.png) |

| Naval ensign 1786–1915 |

|

The Austro-Hungarian Navy was the naval force of Austria-Hungary. Its official name in German was kaiserliche und königliche Kriegsmarine (Imperial and Royal War Navy), abbreviated as k.u.k. Kriegsmarine.

This navy existed under this name after the formation of the Dual Monarchy in 1867 and continued in service until the end of the First World War in 1918. Prior to 1867, the empire's naval forces were those of the Austrian Empire. By 1915 a total of 33,735 naval personnel were serving in the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine.

After the First World War, both Austria and Hungary were deprived of their coasts, and their navy was confiscated by the victorious Allied powers. Their former ports on the Adriatic Sea, such as Trieste, Pola, Fiume, and Ragusa, became parts of Italy and Yugoslavia. (After the break-up of Yugoslavia, its former coast is divided between Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia, and Montenegro.)

Ships of the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine were designated SMS, for Seiner Majestät Schiff (His Majesty's Ship).

History

Origins

Until the end of the 18th century there were only limited attempts to establish an Austrian navy. The Habsburgs had employed armed ships sailing the Danube in the 16th and 17th centuries to fight the Ottoman Empire, and ships guarding the merchant fleet also operated from the Austrian Netherlands, but these forces were neither under a common command nor did they serve a common purpose. After the Seven Years' War Austrian vulnerability to privateers in the Mediterranean Sea led Count Kaunitz to push for the creation of a small force of frigates. A specific Naval Ensign (Marineflagge) based on the red-white-red colours was introduced only in the reign of Emperor Joseph II.

This situation changed considerably in 1797 with the Treaty of Campo Formio between France and Austria. Austria ceded to France the Austrian Netherlands and certain islands in the Mediterranean, including Corfu and some Venetian islands in the Adriatic. Venice and its territories were divided between the two states, and the Austrian emperor received the city of Venice along with Istria and Dalmatia. The substantial Venetian naval forces and facilities were also handed over to Austria and became the basis of the formation of the future Austrian Navy.

The 19th century

In 1802 Archduke Charles of Austria, acting in his role as "Inspector General of the Navy" ordered the formation of a naval cadet academy in Venice (Cesarea regia scuola dei cadetti di marina), which would move to Trieste in 1848 and eventually - under its later name of "Imperial and Royal Naval Academy" (k.u.k. Marine-Akademie) - to Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia), where it remained until World War I.

The navy gained its first influential supporter when Archduke Charles' third son Archduke Friedrich entered the service in 1837. The young archduke introduced many modernizing reforms, aiming to make his country's naval force less "Venetian" and more "Austrian". In 1844 Archduke Friedrich was promoted vice-admiral and Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, but died just one year later at the age of twenty-six.

Austrian warships had their first military encounters during the Oriental Crisis of 1840 as a part of a British-led fleet which ousted the Viceroy of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, from Ottoman Syria. Archduke Friedrich took part in the campaign personally and was awarded the Military Order of Maria Theresa for his exceptional leadership.

Modernising the navy

In 1849 the Dane Hans von Dahlerup was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian Navy. He introduced many personal and other reforms and imposed in the Navy the replacement of the Italian language by the German language. In the following years the strength of the Navy reached 4 frigates, 6 corvettes, 7 brigs, and smaller ships.

In 1854 the younger brother of the reigning Emperor Franz Joseph took office as Commander-in-Chief of the Austrian Navy. Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian was twenty-two at that time. Archduke Friedrich's distant relative was trained for the navy, and threw himself into this new career with much zeal. He carried out many reforms to modernise the naval forces, and was instrumental in creating the naval port at Trieste as well as the battle fleet with which admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff would later secure his victories in the Italian War.

In Venice the naval shipyard was retained. Here the Austrian screw-driven gunboat Kerka (crew: 100) was launched in 1860 (in service until 1908). The Venice 'lagoon flotilla' of Austrian warships was, in 1864, moored in front of the church of San Giorgio and included the screw-driven gunboat Ausluger, the paddle-steamer Alnoch, and five paddle-gunboats of the Types 1 to IV.[1]

Novara Expedition

- Main article: Novara Expedition

Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian also initiated a large-scale scientific expedition (1857–1859) during which the frigate SMS Novara became the first Austrian warship to circumnavigate the globe. The journey lasted 2 years and 3 months and was accomplished under the command of Kommodore Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair, with 345 officers and crew, and 7 scientists aboard. The expedition was planned by the Imperial Academy of Sciences in Vienna and aimed to gain new knowledge in the disciplines of astronomy, botany, zoology, geology, oceanography and hydrography. SMS Novara sailed from Trieste on 30 April 1857, visiting Gibraltar, Madeira, Rio de Janeiro, Cape Town, St. Paul Island, Ceylon, Madras, Nicobar Islands, Singapore, Batavia, Manila, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Puynipet island, Stuarts, Sydney (5 November 1858), Auckland, Tahiti, Valparaiso and Gravosa before returning to Trieste on 30 August 1859.

In 1863 the Royal Navy's battleship HMS Marlborough, the flagship of Admiral Fremantle, made a courtesy visit to Pola, the main port of the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[1]

In April 1864 Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian stepped down as Commander-in-Chief of the Navy and accepted the throne of Mexico from Louis Napoleon, becoming Maximilian I of Mexico. He traveled from Trieste to Veracruz aboard the SMS Novara, escorted by the frigates SMS Bellona (Austrian) and Thémis (French), and the Imperial yacht Phantasie led the warship procession from his palace at Schloß Miramar out to sea.[2] When he was arrested and executed four years later, admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff was sent aboard the Novara to take Ferdinand Maximilian's body back to Austria.

Second Schleswig War

The Second Schleswig War was the 1864 invasion of Schleswig-Holstein by Prussia and Austria. At that time, The duchies were part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Rear-Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff commanded a small Austrian flotilla which traveled from the Mediterranean Sea to the North Sea.

On May 9, 1864, Tegetthoff commanded the Austrian naval forces in the naval action off Heligoland from his flagship, the screw-driven SMS Schwarzenberg.[1] The action was a tactical victory for the Danish forces. It was also the last significant naval action fought by squadrons of wooden ships and the last significant naval action involving Denmark.

Third Italian War of Independence

On 20 July 1866, near the island of Vis (Lissa) in the Adriatic, the Austrian fleet, under the command of Rear-Admiral Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, made its name in the modern era at the Battle of Lissa during the Third Italian War of Independence. The battle pitted Austrian naval forces against the naval forces of the newly created Kingdom of Italy. It was a decisive victory for an outnumbered Austrian over a superior Italian force, and was the first major European sea battle involving ships using iron and steam, and one of the last to involve large wooden battleships and deliberate ramming.

Peace-time

In 1873 the new sail and steam frigate SMS Laudon (crew 480) was added to the fleet, which took part in the International Naval Review off Gruž in 1880.[1]

During peace-time Austrian ships visited Asia, North America, South America, and the Pacific Ocean.

In 1869 Emperor Franz Joseph travelled on board the screw-driven corvette SMS Viribus Unitis (not to be confused with the later battleship of the same name) to the opening of the Suez Canal. The ship had been named after his personal motto.[3]

Polar Expedition

Austro-Hungarian ships and naval personnel were also involved in Arctic exploration, discovering Franz Josef Land during an expedition which lasted from 1872 to 1874.

Led by the naval officer Karl Weyprecht and the infantry officer and landscape artist Julius Payer, the custom-built schooner Tegetthoff left Tromsø in July 1872. At the end of August she got locked in pack-ice north of Novaya Zemlya and drifted to hitherto unknown polar regions. It was on this drift when the explorers discovered an archipelago which they named after Emperor Franz Joseph I.

In May 1874 Payer decided to abandon the ice-locked ship and try to return by sledges and boats. On 14 August 1874 the expedition reached the open sea and on 3 September finally set foot on Russian mainland.

Between the centuries

Crete Rebellion

In late 1896 a rebellion broke out on Crete, and on 21 January 1897 a Greek army landed in Crete to liberate the island from the Ottoman Empire and unite it with Greece. The European powers, including Austria-Hungary, intervened, and proclaimed Crete an international protectorate. Warships of the k.u.k. Kriegsmarine patrolled the waters off Crete in blockade of Ottoman naval forces. Crete remained in an anomalous position until finally ceded to Greece in 1913.

The Boxer Rebellion

Austria-Hungary was part of the Eight-Nation Alliance during the Boxer Rebellion in China (1899–1901). As a member of the Allied nations, Austria sent two training ships and the cruisers SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia, SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth, SMS Aspern, and SMS Zenta and a company of marines to the North China coast in April 1900, based at the Russia concession of Port Arthur.

In June they helped hold the Tianjin railway against Boxer forces, and also fired upon several armed junks on the Hai River near Tong-Tcheou. They also took part in the seizure of the Taku Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by Capt. Roger Keyes of HMS Fame. In all k.u.k. forces suffered few casualties during the rebellion.

After the uprising a cruiser was maintained permanently on the China station, and a detachment of marines was deployed at the embassy in Peking.

Lieutenant Georg Ludwig von Trapp, who would serve as a submarine commander during World War I and become famous in the musical The Sound of Music after World War II, was decorated for bravery aboard SMS Kaiserin und Königin Maria Theresia during the Rebellion.

Montenegro

During the First Balkan War Austria-Hungary joined Germany, France, the United Kingdom and Italy in blockading the seaport town of Bar (Antivari) in the Kingdom of Montenegro.

European naval arms race

Among the many factors giving rise to World War I was the naval arms race between the British Empire and Imperial Germany. Germany enhanced her naval infrastructure, building new dry docks, and enlarging the Kiel Canal to enable larger vessels to navigate it. However, that was not the only European naval arms race. Imperial Russia too had commenced building a new modern navy[4] following their naval defeat in the Russo-Japanese War. The Austro-Hungarian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy were in a race of their own for domination of the Adriatic Sea. The k.u.k. Kriegsmarine had another prominent supporter at that time in the face of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Like other imperial naval enthusiasts before him, Franz Ferdinand had a keen private interest in the fleet and was an energetic campaigner for naval matters.

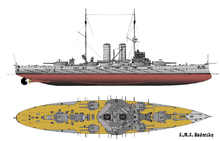

The Dreadnought Era

In 1906 Britain completed the battleship HMS Dreadnought, and it was so advanced that some argued that this rendered all previous battleships obsolete, although Britain and other countries kept pre-dreadnoughts in service.

Austria-Hungary's naval architects, aware of the inevitable dominance of all big gun dreadnought type designs, then presented their case to the Marinesektion des Reichskriegsministeriums (Naval Section at the War Ministry) in Vienna, which on 5 October 1908 ordered the construction of their own dreadnought, the first contract being awarded to 'Werft das Stabilimento Tecnico Triestino (STT)', the naval weaponry to be provided by the Škoda Works in Pilsen. The Marine budget for 1910 was substantially enlarged to permit major refits of the existing fleet and more dreadnoughts. The battleships SMS Tegetthoff and SMS Viribus Unitis were both launched by the Archduke Franz Ferdinand at Trieste, amongst great rejoicing, on 24 June 1911, and 21 March 1912 respectively. They were followed by SMS Prinz Eugen, and SMS Szent István. These battleships, constructed later than many of the earlier British and German dreadnoughts, were considerably ahead in some aspects of design, especially of both the French and Italian navies, and were constructed with Marconi wireless rooms as well as anti-aircraft armaments. It is said they were the first battleships in the world equipped with torpedo launchers built into their bows.[3]

Between 22 and 28 May 1914 Tegetthoff, accompanied by Viribus Unitis, made a courtesy visit to the British Mediterranean fleet in Malta.[3]

Submarine fleet

In 1904, after allowing the navies of other countries to pioneer submarine developments, the Austro-Hungarian Navy ordered the Austrian Naval Technical Committee (MTK) to produce a submarine design. The January 1905 design developed by the MTK and other designs submitted by the public as part of a design competition were all rejected by the Navy as impracticable. They instead opted to order two submarines each of designs by Simon Lake, Germaniawerft, and John Philip Holland for a competitive evaluation. The two Germaniawerft submarines comprised the U-3 class.[5][Note 1] The Navy authorized two boats, U-3 and U-4, from the Germaniawerft in 1906.[6]

The U-3-class was an improved version of Germaniawerft's design for the Imperial German Navy's first U-boat, U-1,[6] and featured a double hull with internal saddle tanks. The Germaniawerft engineers refined the design's hull shape through extensive model trials.[7]

U-3 and U-4 were both laid down on 12 March 1907 at Germaniawerft in Kiel and were launched in August and November 1908, respectively.[7][8][Note 2] After completion, each was towed to Pola via Gibraltar,[7] with U-3 arriving in January 1909 and U-4 arriving in April.[8]

The U-5 class was built to the same design as the C-class for the US Navy[9] and was built by Robert Whitehead's firm of Whitehead & Co. under license from Holland and his company, Electric Boat.[7] Components for the first two Austrian boats were manufactured by the Electric Boat Company and assembled at Fiume, while the third boat was a speculative private venture by Whitehead that failed to find a buyer and was purchased by Austria-Hungary upon the outbreak of World War I.[9]

The U-5-class boats had a single-hulled design with a teardrop-shape that bore a strong resemblance to modern nuclear submarines.[10] The boats were just over 105 feet (32 m) long and displaced 240 tonnes (260 short tons) surfaced, and 273 tonnes (301 short tons) submerged.[7] The torpedo tubes featured unique, cloverleaf-shaped design hatches that rotated on a central axis.[7] The ships were powered by twin 6-cylinder gasoline engines while surfaced, but suffered from inadequate ventilation which resulted in frequent intoxication of the crew.[5] While submerged, they were propelled by twin electric motors.[7] Three boats were built in the class: U-5, U-6, and U-12.

World War I

After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in 1914, the Austro-Hungarian Navy honoured them with a lying in state aboard SMS Viribus Unitis.

During the First World War, the navy saw some action, but prior to the Italian entry spent much of its time in its major naval base at Pola, except for small skirmishes. Following the Italian declaration of war the mere fact of its existence tied up the Italian Navy and the French Navy in the Mediterranean for the duration of the war.

Following the declaration of war in August 1914 the French and Montenegrin forces attempted to cause havoc at Cattaro, KuK Kriegsmarine's southernmost base in the Adriatic. Throughout September, October and November 1914 the navy bombarded the Allied forces resulting in a decisive defeat for the latter, and again in January 1916 in what was called the Battle of Lovćen, which was instrumental in Montenegro being knocked out of the war early.

On 15 May 1915, when Italy declared war on Austria-Hungary, the Austro-Hungarian navy left their harbors in Pola (today Pula, Croatia), Sebenico (today Šibenik, Croatia) and Cattaro (today Kotor, Montenegro) to bombard the eastern Italian coast between Venice and Barletta. Main targets were the cities of Ancona, Rimini, Vieste, Manfredonia, Barletta and bridges and railway tracks along the coast. By 1917 the Austro-Hungarian fleet was as yet largely undamaged.

The presence of three Allied navies in the Mediterranean made any measures of their co-ordination and common doctrine extraordinarily difficult. The Mediterranean was divided into eleven zones, of which the British naval authorities were responsible for four, the French for four, and the Italians for three. Differing command structures, national pride and the language barrier all contributed to a lack of cohesion in the application of Allied sea power, producing a situation in which German and Austro-Hungarian U-boat attacks on shipping flourished. An example of the lack of co-ordination was the sinking of the Italian troop transport Minas bound from Italy to Salonika, which was torpedoed in one of the British zones in February 1917 with the loss of 870 lives, a British escort not understanding a message and failing to relieve the Italian destroyer, which turned around at the zone barrier.

Battle at Durazzo

In December 1915 a k.u.k. Kriegsmarine cruiser squadron attempted to make a raid on the Serbian troops evacuating Albania. After sinking a French submarine and bombarding the town of Durazzo the squadron ran into a minefield, sinking one destroyer and damaging another. The next day the group ran into a squadron of British, French, and Italian cruisers and destroyers. The resulting battle left two Austrian destroyers sunk and light damage to another, while dealing only minor damage to the Allied warships and others.

A three-power conference on 28 April 1917, at Corfu, discussed a more offensive strategy in the Adriatic, but the Italians were not prepared to consider any big ship operations, considering the size of the Austro-Hungarian fleet. The British and French seemed reluctant to move alone against the Austro-Hungarians, especially if it meant a full-scale battle. But the Austrians were not inactive either, and even as the Allied conference was in session they were planning an offensive operation against the Otranto Barrage.

Battle of the Otranto Straits

Throughout 1917 the Adriatic remained the key to the U-boat war on shipping in the Mediterranean. Cattaro, some 140 miles above the narrow Straits of Otranto, was the main U-boat base from which almost the entire threat to Mediterranean shipping came.

The Otranto Barrage, constructed by the Allies with up to 120 naval drifters, used to deploy and patrol submarine nets, and 30 motor launches, all equipped with depth-charges, was designed to stop the passage of U-boats from Cattaro. However, this failed to do so, and from its inception in 1916, the barrage had caught only two U-boats, the Austrian U-6 and the German UB-44 out of hundreds of possible passages.

However, the barrage effectively meant that the Austro-Hungarian surface fleet could not leave the Adriatic Sea unless it was willing to give battle to the blocking forces. This, and as the war drew on bringing supply difficulties especially coal, plus a fear of mines, limited the Austro-Hungarian navy to shelling the Italian and Serbian coastlines.

There had already been four small-scale Austro-Hungarian attacks on the barrage, on 11 March, 21 and 25 April and 5 May 1917, but none of them amounted to anything. Now greater preparations were made, with two U-boats despatched to lay mines off Brindisi with a third patrolling the exits in case Anglo-Italian forces were drawn out during the attack. The whole operation was timed for the night of 14/15 May, which led to the biggest battle of the Austro-Hungarian navy in World War I, the Battle of the Otranto Straits.

The first Austro-Hungarian warships to strike were the two destroyers, SMS Csepel and SMS Balaton. An Italian convoy of three ships, escorted by the destroyer Borea, was approaching Valona, when, out of the darkness, the Austrians fell upon them. Borea was left sinking. Of the three merchant ships, one loaded with ammunition was hit and blown up, a second set on fire, and the third hit. The two Austrian destroyers then steamed off northward.

Meanwhile, three Austro-Hungarian cruisers under the overall command of Captain Miklós Horthy, SMS Novara, SMS Saida, and Helgoland, had actually passed a patrol of four French destroyers north of the barrage, and thought to be friendly ships passed unchallenged. They then sailed through the barrage before turning back to attack it. Each Austrian cruiser took one-third of the line and began slowly and systematically to destroy the barrage with their 10-centimetre (4 in) guns, urging all Allies on board to abandon their ships first.

During this battle the Allies lost two destroyers, 14 drifters and one glider while the Austro-Hungarian navy suffered only minor damage (Novara's steam supply pipes were damaged by a shell) and few losses. The Austro-Hungarian navy returned to its bases up north in order to repair and re-supply, and the allies had to rebuild the blockade.

The Mutiny of 1918

In February 1918 a mutiny started in the 5th Fleet stationed at the Gulf of Cattaro naval base. Sailors on up to 40 ships joined the mutiny over demands for better treatment and a call to end the war.

The mutiny failed to spread beyond Cattaro, and within three days a loyal naval squadron had arrived. Together with coastal artillery the squadron fired several shells into a few of the rebel's ships, and then assaulted them with k.u.k. Marine Infantry in a short and successful skirmish. About 800 sailors were imprisoned, dozens were court-martialed, and four seamen were executed, including the leader of the uprising, Franz Rasch, a Bohemian. Given the huge crews required in naval vessels of that time this is an indication that the mutiny was limited to a minority.

Late World War I

A second attempt to force the blockade took place in June 1918 under the command of Rear-Admiral Horthy. A surprise attack was planned, but the mission was doomed when the fleet was by chance spotted by an Italian MAS boat patrol, commanded by Luigi Rizzo that had already sunk, at anchor, the 25 year-old battleship SMS Wien (5,785 tons) the year before. Rizzo's MAS boat launched two torpedoes, hitting one of the four Austrian dreadnoughts, the SMS Szent István which had already slowed down due to engine problems. The element of surprise lost, Horthy broke off his attack. Huge efforts were made by the crew to save Szent István, which had been hit below the water-line, and the dreadnaught battleship Tegetthoff took her in tow until a tug arrived. However just after 6 a.m., the pumps being unequal to the task, the ship, now listing badly, had to be abandoned. Szent István sank soon afterwards, taking 89 crewmen with her. The event was filmed from a sister ship.[3]

In 1918, in order to avoid having to give the fleet to the victors, the Austrian Emperor handed down the entire Austro-Hungarian Navy and merchant fleet, with all harbours, arsenals and shore fortifications to the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs.The state of SCS was proclaimed officially on 29 October 1918. They in turn sent diplomatic notes to the governments of France, the United Kingdom, Italy, the United States and Russia, to notify them that the State of SCS was not at war with any of them and that the Council had taken over the entire Austro-Hungarian fleet. Austria asked for an armistice on 29 October.

However, on 1 November 1918 the navy underwent an attack at its moorings by the Italian Regia Marina: supposedly without knowing about the Emperor's move, two men of the Regia Marina, Raffaele Paolucci and Raffaele Rossetti, rode a primitive manned torpedo (nicknamed the Mignatta or "leech") into the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola. Using limpet mines, they then sank the anchored Viribus Unitis, with considerable loss of life, as well as the freighter Wien.[11] The French navy commandeered the new dreadnought SMS Prinz Eugen, which they took to France and later used it for target practice in the Atlantic, where it was destroyed.[3]

Ships lost

Ships lost in World War I: [12]

- 1914: SMS Kaiserin Elisabeth (Siege of Tsingtao, 1914), SMS Zenta

- 1915: SM U-12, SM U-3, SMS Lika, SMS Triglav

- 1916: SM U-6, SM U-16

- 1917: SM U-30, SMS Wildfang, SMS Wien, SMS Inn (sunk by a Romanian mine)[13][14][15]

- 1918: SM U-23, SMS Streiter, SM U-20, SM U-10, SMS Szent István, SMS Viribus Unitis

Ships lost after World War I:

Ports and locations

The home port of the Austro-Hungarian Navy was the Seearsenal (naval base) at Pola (now Pula, Croatia), a role it took over from Venice, where the early Austrian Navy had been based. Supplementary bases included the busy port of Trieste and the natural harbour of Cattaro (now Kotor, Montenegro) at the most southerly point of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Both Trieste and Pola had major shipbuilding facilities.[1] Pola's naval installations contained one of the largest floating drydocks in the Mediterranean. The city of Pola was also the site of the central church of the navy "Stella Maris" (k.u.k. Marinekirche "Stella Maris"), of the Austro-Hungarian Naval Observatory and the empire's naval military cemetery (k.u.k. Marinefriedhof).[16] In 1990, the cemetery was restored after decades of neglect by the communist regime in Yugoslavia. The Austro-Hungarian Naval Academy (k.u.k. Marine-Akademie) was located in Fiume (now Rijeka, Croatia).

Trieste was also the headquarters of the merchant line Österreichischer Lloyd (founded in 1836 and, later, Lloyd Triestino; now Italia Marittima), whose headquarters stood at the corner of the Piazza Grande and Sanita. By 1913, Österreichischer Lloyd had a fleet of 62 ships comprising a total of 236,000 tons.[1]

Naval aviation: the K.u.K. Seefliegerkorps

In August 1916, the Imperial and Royal Naval Air Corps or K.u.K. Seeflugwesen was established. In 1917 it was rechristened the K.u.K. Seefliegerkorps. Its first aviators were naval officers who received their initial pilot training at the airfields of Wiener Neustadt in Lower Austria, where the Theresian Military Academy is also located. They were first assigned for tours aboard the Tegetthoff-class battleships. Later, the k.u.k. Seefliegerkorps also served at the following airfields in Albania and southern Dalmatia: Berat, Kavaja, Tirana, Scutari and Igalo. They also had airfields at Podgorica in Montenegro.

- Flik 1 - Igalo from June - November 1918

- Flik 6 - Igalo from November 1915 - January 1916

- - Scutari from January 1916 - June 1917

- - Tirana from July 1917 - June 1918

- - Banja from June - July 1918

- - Tirana from July - September 1918

- - Podgorica from September - November 1918

- Flik 13 - Berat from August - September 1918

- - Kavaja from September - October 1918

The following Austrian squadrons served at Feltre also:

- Flik 11 - from February 1918

- Flik 14 - from June 1918 to November 1918

- Flik 16 - from November 1917 - October 1918

- Flik 31 - from June - July 1918

- Flik 36 - from June - July 1918

- Flik 39 - from January - May 1918

- Flik 45 - during April 1918

- Flik 56 - during December 1917

- Flik 60J - from March - September 1918

- Flik 66 - from January 1918 - November 1918

- Flik 101 - during May 1918

Feltre was captured by Austrian forces on 12 November 1917 after the Battle of Caporetto. There were two other military airfields nearby, at Arsie and Fonzaso. It was the main station for the Austrian naval aviators in that area. The K.u.K. Seeflugwesen used mostly modified German planes, but produced several variations of its own. Notable planes for the service were the following:

- Fokker A.III

- Fokker E.III

- Hansa-Brandenburg B.I

- Hansa-Brandenburg D.I

- Aviatik D.I

- Albatros D.III

- Phönix D.I

- Fokker D.VII

- Lohner L

Problems affecting the navy

When it came to its financial and political position within the Empire, the Austrian (and later Austro-Hungarian) Navy was a bit of an afterthought for most of the time it existed.

One reason was that sea power was never a priority of the Austrian foreign policy and that the Navy itself was relatively little known and supported by the public. Activities such as open days and naval clubs were unable to change the sentiment that the Navy was just something "expensive but far away". Another point was that naval expenditures were for most of the time overseen by the Austrian War Ministry, which was largely controlled by the Army, the only exception being the period before the Battle of Lissa.

The Navy was only able to draw significant public attention and funds during the three short periods it was actively supported by a member of the Imperial Family. The Archdukes Friedrich (1821–1847), Ferdinand Maximilian (1832–1867) and Franz Ferdinand (1863–1914) each a keen private interest in the fleet, held senior naval ranks and were energetic campaigners for naval matters. However, none lasted long as, Archduke Friedrich died early, Ferdinand Maximilian left Austria to become Emperor of Mexico and Franz Ferdinand was assassinated before he acceeded the throne.

The Navy's problems were further exacerbated by the eleven different ethnic groups comprising the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Officers had to speak at least four of the languages found in the Empire. Germans and Czechs generally were in signals and engine room duties, Hungarians became gunners, while Croats and Italians were seamen or stokers. The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 aimed to calm political dissatisfaction by creating the Dual Monarchy, in which the Emperor of Austria was also the King of Hungary. This constitutional change was also reflected in the navy's title, which changed to "Imperial and Royal Navy" (kaiserlich und königliche Kriegsmarine, short form K. u K. Kriegsmarine).

Besides problems stemming from the difficulty of communicating efficiently within such a multilingual military, the Empire's battleship designs were generally a smaller tonnage than those of other European powers.

Notable personnel

- Archduke Franz Ferdinand, Admiral. Commander-in-Chief of the Navy

- Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian,Viceadmiral. Commander-in-Chief of the Navy

- Ludwig von Fautz, Viceadmiral. Commander-in-Chief of the Navy and Secretary of the Navy

- Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, Viceadmiral of the mid-19th century, known for his role in the Battle of Lissa (1866). He was probably the most famous Austrian sailor, later also Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.

- Maximilian von Sterneck, Admiral. Fought at Lissa, was a benefactor of the city of Pola and Commander-in-Chief of the Navy.

- Karl Weyprecht, Arctic explorer. One of the leaders of the Austro-Hungarian North Pole Expedition from 1872 to 1874.

- Bernhard von Wüllerstorf-Urbair, Viceadmiral. Leader of the Novara Expedition from 1857 to 1859, later Imperial Minister of Trade.

- Gottfried von Banfield, Austria-Hungary's most successful naval aviator in World War I. Later a businessman in Trieste.

- Miklós Horthy, Viceadmiral in World War I and last commander of the Austro-Hungarian fleet. Later Regent of Hungary until 1944.

- Georg Ludwig von Trapp, Austrian submarine officer in World War I. Later a businessman and head of the famous Von Trapp Family Singers featured in the musical The Sound of Music.

- Ludwig von Höhnel, Austrian naval officer and explorer of Africa.

- Julius von Wagner-Jauregg, physician and officer in the Austro-Hungarian Naval Reserve. Later awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1927.

Ranks and rates of the Navy (in English)

Enlisted ratings

- Matrose

- Seaman (Matrose 1. klasse)

- Able seaman (Marsgast)

- Leading rate

- Petty officer 3rd Class

- Petty officer 2nd Class

- Petty officer 1st Class

Officer cadets

- Sea aspirant

- Sea cadet

- Sea ensign

Officers

- Frigate ensign (until 1860)

- Ship of the line Ensign (until 1908)

- Corvette lieutenant (reserve officer's rank)

- Frigate lieutenant (from 1908)

- Ship-of-the-line lieutenant

- Corvette captain

- Frigate captain

- Ship-of-the-line captain

- Counter admiral

- Vice admiral

- Admiral

- Grand admiral

Senior leadership

Commanders-in-Chief of the Navy

(in German Oberkommandant der Marine. From March 1868 the incumbents of this position were styled Marinekommandant)

- Hans Birch Dahlerup, VAdm. (February 1849–August 1851)

- Franz Graf Wimpffen, VAdm., (August 1851–September 1854)

- Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian of Austria, VAdm. (September 1854–1861)

- Ludwig von Fautz, VAdm. (1861–March 1865)

- Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, VAdm. (March 1868–April 1871)

- Friedrich von Pöck, Adm. (April 1871–November 1883)

- Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck, Adm. (November 1883–December 1897)

- Hermann von Spaun, Adm. (December 1897–October 1904)

- Graf Rudolf Montecuccoli, Adm. (October 1904–February 1913)

- Anton Haus, Adm./GAdm. (February 1913–February 1917)

- Maximilian Njegovan, Adm. (April 1917–February 1918)

Commanders-in-Chief of the Fleet (1914–1918)

(in German Flottenkommandant)

- Anton Haus, Adm./GAdm (July 1914–February 1917)

- Maximilian Njegovan, Adm. (February 1917–February 1918)

- Miklós Horthy, KAdm./VAdm. (February 1918–November 1918)

Heads of the Naval Section at the War Ministry

(in German Chef der Marinesektion at the Kriegsministerium)

- Ludwig von Fautz, VAdm. (March 1865–April 1868)

- Wilhelm von Tegetthoff, VAdm.(March 1868–April 1871)

- Friedrich von Pöck, Adm. (October 1872–November 1883)

- Maximilian Daublebsky von Sterneck, Adm. (November 1883–December 1897)

- Hermann von Spaun, Adm. (December 1897–October 1904)

- Rudolf Montecuccoli, Adm. (October 1904–February 1913)

- Anton Haus, Adm./GAdm. (February 1913–February 1917)

- Karl Kailer von Kaltenfels, VAdm. (February 1917–April 1917)

- Maximilian Njegovan, Adm. (April 1917–February 1918)

- Franz von Holub, VAdm. (February 1918–November 1918)

Constructors General

(in German Generalschiffbauingenieur)

- Siegfried Popper, (1904–April 1907)

- Franz Pitzinger, (November 1914–1918)

Naval ensign

.svg.png)

Until Emperor Joseph II. authorized a naval ensign on 20 March 1786, Austrian naval vessels used the yellow and black imperial flag. The flag, formally adopted as Marineflagge (naval ensign) was based on the colours of the Archduchy of Austria. It served as the official flag also after the Ausgleich in 1867, when the Austrian navy became the Austro-Hungarian Navy.[17] During World War I, Emperor Franz Joseph approved of a new design, which also contained the Hungarian arms. This flag, officially instituted in 1915, was however little used, and ships continued displaying the old Ensign until the end of the war. Photographs of Austro-Hungarian ships flying the post-1915 form of the Naval Ensign are therefore relatively rare.

See also

- List of ships of the Austro-Hungarian Navy

- List of Austro-Hungarian U-boats

- The Adriatic Campaign of World War I

- Mediterranean naval engagements during World War I

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hubmann, Franz, & Wheatcroft, Andrew (editor), The Habsburg Empire, 1840–1916, London, 1972, ISBN 0-7100-7230-9

- ↑ Haslip, Joan, Imperial Adventurer - Emperor Maximilian of Mexico, London, 1971, ISBN 0-297-00363-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wagner, Walter, & Gabriel, Erich, Die 'Tegetthoff' Klasse, Vienna, January 1979.

- ↑ Greger, René; & Watts, A. J. (1972). The Russian fleet, 1914-1917. London: Ian Allan. ISBN 0-7110-0255-X

- 1 2 Gardiner, p. 340.

- 1 2 Gibson and Prendergast, p. 384.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gardiner, p.342.

- 1 2 Sieche, p. 19.

- 1 2 Fontenoy, Paul E. (2007). Submarines: an illustrated history of their impact. ABC-CLIO. p. 156. ISBN 978-1-85109-563-6.

- ↑ Sieche, p. 21.

- ↑ Warhola, Brian (January 1998). "Assault on the Viribus Unitis". Old News. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ↑ Dario Petković: Ratna mornarica austro-ugarske monarhije, Pula 2004, Page 86, ISBN 953-6250-80-2

- ↑ Angus Konstam, Gunboats of World War I, p. 29

- ↑ René Greger, Austro-Hungarian warships of World War I, p. 142

- ↑ Mark Axworthy, Cornel I. Scafeș, Cristian Crăciunoiu, Third Axis, Fourth Ally: Romanian Armed Forces in the European War, 1941-1945, p. 327

- ↑ Naval cemetery - a walk through the history of Pula

- ↑ Alfred Freiherr von Koudelka: Unsere Kriegs-Marine. Vienna, 1899, pp.60-2

Literature

- Donko, Wilhelm, "A Brief History of the Austrian Navy", published by epubli.de GmbH Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-8442-2129-9; 120 pages (English) - printed version and e-book

- Hauke, Erwin; Schroeder, Walter; Tötschinger, Bernhard (1988). Die Flugzeuge der k.u.k. Luftfahrtruppe und Seeflieger, 1914–1918. Graz: H. Weishaupt.

- Kemp, Peter, The Otranto Barrage, in History of the First World War, vol.6, no.1, BPC Publishing Ltd., Bristol, England, 1971, pps: 2265 -2272.

- Schupita, Peter (1983). Die k.u.k. Seeflieger: Chronik und Dokumentation der österreichisch-ungarischen Marineluftwaffe, 1911–1918. Koblenz: Bernard und Grafe.

- Sokol, Anthony (1968). The Imperial and Royal Austro-Hungarian Navy. Annapolis: United States Naval Institute.

Literary fiction

British author John Biggins wrote a series of four serio-comic historical novels concerning the Austro-Hungarian Navy and a fictional hero named Ottokar Prohaska, although genuinely historical individuals, such as Georg Ludwig von Trapp and Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria make appearances. Published by McBooks Press, the novels are:

- A Sailor of Austria: In Which, Without Really Intending to, Otto Prohaska Becomes Official War Hero No. 27 of the Habsburg Empire

- The Emperor's Coloured Coat: In Which Otto Prohaska, Hero of the Habsburg Empire, Has an Interesting Time While Not Quite Managing to Avert the First World War

- The Two-Headed Eagle: In Which Otto Prohaska Takes a Break as the Habsburg Empire's Leading U-boat Ace and Does Something Even More Thanklessly Dangerous

- Tomorrow the World: In which Cadet Otto Prohaska Carries the Habsburg Empire's Civilizing Mission to the Entirely Unreceptive Peoples of Africa and Oceania

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to k.u.k. Kriegsmarine. |

- The Genesis of the Austrian Navy - A Chronology

- k.u.k. Kriegsmarine - Austro-Hungarian Navy officer rank insignia

- Society for Research of the imperial and royal navy (k.u.k. Marine) "Viribus unitis" - Pula

- Austro-Hungarian Navy in World War 1, 1914-18 including ship losses

- Austro-Hungarian Navy Deployment, 1914

- Austro-Hungarian Danube Flotilla 1914

- The Austro-Hungarian Submarine Force

- Viribus Unitis

- Antique Photography & Postcards of Austro-Hungarian army 1866-1918 (English)

.jpg)