Pan Am Flight 214

The aircraft involved in the crash, N709PA, before being delivered to Pan Am | |

| Accident summary | |

|---|---|

| Date | December 8, 1963 |

| Summary | Lightning strike |

| Site |

Elkton, Maryland, United States 39°36′28″N 75°47′20″W / 39.60778°N 75.78889°WCoordinates: 39°36′28″N 75°47′20″W / 39.60778°N 75.78889°W |

| Passengers | 73 |

| Crew | 8 |

| Fatalities | 81 (all) |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 707-121 |

| Aircraft name | Clipper Tradewind |

| Operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N709PA |

| Flight origin | Luis Muñoz Marín Int'l Airport |

| Stopover | Baltimore/Washington Int'l Airport |

| Destination | Philadelphia Int'l Airport |

Pan Am Flight 214 was a scheduled flight of Pan American World Airways from San Juan, Puerto Rico, to Baltimore, Maryland, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. On December 8, 1963, the Boeing 707 serving the flight crashed near Elkton, Maryland, while en route from Baltimore to Philadelphia, after being hit by lightning, killing all 81 on board.[1] The accident is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records (2005) as the "Worst Lightning Strike Death Toll."[2][nb 1] It remains the deadliest airplane crash in Maryland state history.

Flight history

At 4:10 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (EST) on December 8, 1963, Pan American Flight 214, a Boeing 707-121 jet airliner, registration N709PA,[3] nicknamed Clipper Tradewind (this happened to be the first jet delivered to a United States airline[4]), departed Isla Verde International Airport in San Juan, Puerto Rico. It landed as scheduled at Baltimore's Friendship Airport (now Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport, or BWI), and 69 passengers disembarked.

At 8:24 p.m., Flight 214 departed for Philadelphia with 73 passengers and eight crew members on board. Because of high winds in the area, the crew chose to wait in a holding pattern with five other airplanes, rather than attempt to land in Philadelphia.[5]

At 8:58 p.m., while in the holding pattern, the aircraft exploded. The crew managed to transmit a final message – "Mayday, mayday, mayday ... Clipper 214 out of control ... here we go" – before crashing near Elkton, Maryland. All 81 people on board were killed.[6]

Investigation

The Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) investigated the accident and issued the following Probable Cause statement on March 3, 1965:[5]

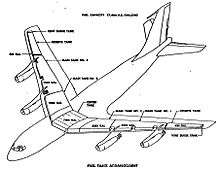

Probable Cause: Lightning-induced ignition of the fuel/air mixture in the no. 1 reserve fuel tank with resultant explosive disintegration of the left outer wing and loss of control.

In response to the CAB's findings, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) asked operators to install lightning discharge wicks (or static dischargers) on all commercial jets flying in US airspace.[7]

Volatile fuel vapor recommendation

On December 17, 1963, nine days after the crash of flight 214, Leon H. Tanguay, director of the CAB Bureau of Safety, sent a letter to the FAA recommending several safety modifications as part of future aircraft design. One modification related specifically to volatile fuel vapors that can form inside partly empty fuel tanks, which may be ignited by various potential ignition sources and cause an explosion. Tanguay's letter suggested reducing the volatility of the fuel/air gas mixture by introducing an inert gas, or by using air circulation.[1] Thirty-three years later[nb 2] a similar recommendation was issued by the NTSB (the CAB Bureau of Safety's successor) after the TWA Flight 800 Boeing 747 crash on July 17, 1996, with 230 fatalities, which was also deemed to have been caused by the explosion of a volatile mixture inside a fuel tank.[8]

See also

- Aviation safety

- List of accidents and incidents involving commercial aircraft

- TWA flight 800 - Another Fuel tank Explosion after a spark ignited vapors in the fuel tanks.

Notes and citations

- Notes

- ↑ In 1971, LANSA Flight 508 was also brought down by a lightning strike. However, though this crash would have more total casualties (91 fatalities), up to fourteen passengers survived the crash but perished waiting for help in the Peruvian jungle.

- ↑ The full TWA 800 National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) report was issued in 2000, but a safety recommendation regarding fuel vapor inerting was sent to the FAA on December 13, 1996, according to the NTSB report

- Citations

- 1 2 "Pan Am Flight 214 CAB report (PDF) (Historical Aircraft Accident, 1963, Pan Am)" (PDF).

- ↑ archive.org copy of Guinness Book of World Records entry for Pan Am flight 214

- ↑ "FAA Registry". Federal Aviation Administration.

- ↑ McClement, Fred (1966). It Doesn't Matter Where You Sit. Toronto/Montreal: McClelland and Stewart. p. 19. OCLC 955544.

- 1 2 Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 2006-06-12.

- ↑ "Civil Aeronautics Board report". Retrieved 2006-06-12.

- ↑ McClement, p. 22.

- ↑ TWA 800 NTSB AAR-00/03 Final Report, adopted August 23, 2000

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pan Am Flight 214. |

- Civil Aeronautics Board reports (digitized versions).

- A Pan American promotional film that features Clipper Tradewind (N709PA)

- A picture of the aircraft involved in the accident (archived from the original on 2012-11-04)

- Another picture of the accident aircraft

- Another picture of the ill-fated 707