Ventricular tachycardia

| Ventricular tachycardia | |

|---|---|

|

| |

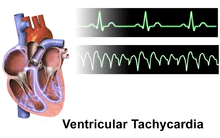

| A run of ventricular tachycardia as seen on a rhythm strip | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | cardiology |

| ICD-10 | I47.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 427.1 |

| DiseasesDB | 13819 |

| MedlinePlus | 000187 |

| eMedicine | emerg/634 med/2367 ped/2546 |

| MeSH | D017180 |

Ventricular tachycardia (V-tach or VT) is a type of regular and fast heart rate that arises from improper electrical activity in the ventricles of the heart.[1] Although a few seconds may not result in problems, longer periods are dangerous.[1] Short periods may occur without symptoms or present with lightheadedness, palpitations, or chest pain.[2] Ventricular tachycardia may result in cardiac arrest and turn into ventricular fibrillation.[1][2] Ventricular tachycardia is found initially in about 7% of people in cardiac arrest.[2]

Ventricular tachycardia can occur due to coronary heart disease, aortic stenosis, cardiomyopathy, electrolyte problems, or a heart attack.[1][2] Diagnosis is by an electrocardiogram (ECG) showing a rate of greater than 120 bpm and at least three wide QRS complexes in a row. It is classified as non-sustained versus sustained based on whether or not it lasts less than or more than 30 seconds. The term "ventricular tachycardias" refers to the group of irregular heartbeats that includes ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation, and torsades de pointes.[2]

In those who have a normal blood pressure and strong pulse, the antiarrhythmic medication procainamide may be used.[2] Otherwise immediate cardioversion is recommended.[2] In those in cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and defibrillation is recommended. Biphasic defibrillation may be better than monophasic. While waiting for a defibrillator, a precordial thump may be attempted in those on a heart monitor who are seen to go into an unstable ventricular tachycardia.[3] In those with cardiac arrest due to ventricular tachycardia survival is about 45%. An implantable cardiac defibrillator or medications such as calcium channel blockers or amiodarone may be used to prevent recurrence.[2]

Signs and symptoms

While a few seconds may not result in problems longer periods are dangerous.[1] Short periods may occur without symptoms or present with lightheadedness, palpitations, or chest pain.[2] Ventricular tachycardia may result in cardiac arrest and turn into ventricular fibrillation.[1][2]

Cause

Ventricular tachycardia can occur due to coronary heart disease, aortic stenosis, cardiomyopathy, electrolyte problems, or a heart attack.[1][2]

Pathophysiology

The morphology of the tachycardia depends on its cause.

In monomorphic ventricular tachycardia, all the beats look the same because the impulse is either being generated from increased automaticity of a single point in either the left or the right ventricle, or due to a reentry circuit within the ventricle. The most common cause of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia is myocardial scarring from a previous myocardial infarction (heart attack). This scar cannot conduct electrical activity, so there is a potential circuit around the scar that results in the tachycardia. This is similar to the re-entrant circuits that are the cause of atrial flutter and the re-entrant forms of supraventricular tachycardia. Other rarer congenital causes of monomorphic VT include right ventricular dysplasia, and right and left ventricular outflow tract VT.

Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, on the other hand, is most commonly caused by abnormalities of ventricular muscle repolarization. The predisposition to this problem usually manifests on the ECG as a prolongation of the QT interval. QT prolongation may be congenital or acquired. Congenital problems include long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. Acquired problems are usually related to drug toxicity or electrolyte abnormalities, but can occur as a result of myocardial ischemia. Class III anti-arrhythmic drugs such as sotalol and amiodarone prolong the QT interval and may in some circumstances be pro-arrhythmic. Other relatively common drugs including some antibiotics and antihistamines may also be a danger, in particular in combination with one another. Problems with blood levels of potassium, magnesium and calcium may also contribute. High-dose magnesium is often used as an antidote in cardiac arrest protocols.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of ventricular tachycardia is made based on the rhythm seen on either a 12-lead ECG or a telemetry rhythm strip. It may be very difficult to differentiate between ventricular tachycardia and a wide-complex supraventricular tachycardia in some cases. In particular, supraventricular tachycardias with aberrant conduction from pre-existing bundle branch block are commonly misdiagnosed as ventricular tachycardia. Other rarer phenomena include ashman beats and antedromic atrioventricular re-entry tachycardias.

Various diagnostic criteria have been developed to determine whether a wide complex tachycardia is ventricular tachycardia or a more benign rhythm.[4][5] In addition to these diagnostic criteria, if the individual has a past history of a myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, or recent angina, the wide complex tachycardia is much more likely to be ventricular tachycardia.[6]

The proper diagnosis is important, as the misdiagnosis of supraventricular tachycardia when ventricular tachycardia is present is associated with worse prognosis. This is particularly true if calcium channel blockers, such as verapamil, are used to attempt to terminate a presumed supraventricular tachycardia.[7] Therefore, it is wisest to assume that all wide complex tachycardia is VT until proven otherwise.

Classification

Ventricular tachycardia can be classified based on its morphology:

- Monomorphic ventricular tachycardia means that the appearance of all the beats match each other in each lead of a surface electrocardiogram (ECG).

- Scar-related monomorphic ventricular tachycardia is the most common type and a frequent cause of death in patients having survived a heart attack or myocardial infarction, especially if they have weak heart muscle.[8]

- RVOT tachycardia is a type of monomorphic ventricular tachycardia originating in the right ventricular outflow tract. RVOT morphology refers to the characteristic pattern of this type of tachycardia on an ECG.

- Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia, on the other hand, has beat-to-beat variations in morphology. This may appear as a cyclical progressive change in cardiac axis, previously referred to by its French name torsades de pointes ("twisting of the spikes"). However, at the current time, the term torsades de pointes is reserved for polymorphic VT occurring in the context of a prolonged resting QT interval.

Another way to classify ventricular tachycardias is the duration of the episodes: Three or more beats in a row on an ECG that originate from the ventricle at a rate of more than 100 beats per minute constitute a ventricular tachycardia.

- If the fast rhythm self-terminates within 30 seconds, it is considered a non-sustained ventricular tachycardia.

- If the rhythm lasts more than 30 seconds, it is known as a sustained ventricular tachycardia (even if it terminates on its own after 30 seconds).

A third way to classify ventricular tachycardia is on the basis of its symptoms: Pulseless VT is associated with no effective cardiac output, hence, no effective pulse, and is a cause of cardiac arrest. In this circumstance, it is best treated the same way as ventricular fibrillation (VF), and is recognized as one of the shockable rhythms on the cardiac arrest protocol. Some VT is associated with reasonable cardiac output and may even be asymptomatic. The heart usually tolerates this rhythm poorly in the medium to long term, and patients may certainly deteriorate to pulseless VT or to VF.

Less common is ventricular tachycardia that occurs in individuals with structurally normal hearts. This is known as idiopathic ventricular tachycardia and in the monomorphic form coincides with little or no increased risk of sudden cardiac death. In general, idiopathic ventricular tachycardia occurs in younger individuals diagnosed with VT. While the causes of idiopathic VT are not known, in general it is presumed to be congenital, and can be brought on by any number of diverse factors.

Treatment

Therapy may be directed either at terminating an episode of the arrhythmia or at suppressing a future episode from occurring. The treatment for stable VT is tailored to the specific patient, with regard to how well the individual tolerates episodes of ventricular tachycardia, how frequently episodes occur, their comorbidities, and their wishes. Patients suffering from pulseless VT or unstable VT are hemodynamically compromised and require immediate cardioversion.[9]

Cardioversion

If a person still has a pulse, it is usually possible to terminate the episode using cardioversion.[10] This should be synchronized to the heartbeat if the waveform is monomorphic if possible, in order to avoid degeneration of the rhythm to ventricular fibrillation.[10] An initial energy of 100J is recommended.[10] If the waveform is polymorphic, then higher energies and an unsynchronized shock should be provided (also known as defibrillation).[10] As this is uncomfortable, shocks should ideally only be delivered only to a someone who is unconscious or sedated.

Defibrillation

A person with pulseless VT is treated the same as ventricular fibrillation with high-energy (360J with a monophasic defibrillator, or 200J with a biphasic defibrillator) unsynchronised cardioversion (defibrillation).[10] They will be unconscious.

The shock may be delivered to the outside of the chest using the two pads of an external defibrillator, or internally to the heart by an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) if one has previously been inserted.

An ICD may also be set to attempt to overdrive pace the ventricle. Pacing the ventricle at a rate faster than the underlying tachycardia can sometimes be effective in terminating the rhythm. If this fails after a short trial, the ICD will usually stop pacing, charge up and deliver a defibrillation grade shock.

Medication

For those who are stable with a monomorphic waveform the medications procainamide or sotalol may be used and are better than lidocaine.[11] Evidence does not show that amiodarone is better than procainamide.[11]

As a low magnesium level in the blood is a common cause of VT, magnesium sulfate can be given for torsades de pointes or if a low blood magnesium level is found/suspected.

Long-term anti-arrhythmic therapy may be indicated to prevent recurrence of VT. Beta-blockers and a number of class III anti-arrhythmics are commonly used.

Surgery

An implantable ICD is more effective than drug therapy for prevention of sudden cardiac death due to VT and VF, but may be constrained by cost issues, as well as patient co-morbidities and patient preference.

Catheter ablation is a possible treatment for those with recurrent VT.[12] Remote magnetic navigation is one effective method to do the procedure.[13]

There was consensus among the task force members that catheter ablation for VT should be considered early in the treatment of patients with recurrent VT. In the past, ablation was often not considered until pharmacological options had been exhausted, often after the patient had suffered substantial morbidity from recurrent episodes of VT and ICD shocks. Antiarrhythmic medications can reduce the frequency of ICD therapies, but have disappointing efficacy and side effects. Advances in technology and understanding of VT substrates now allow ablation of multiple and unstable VTs with acceptable safety and efficacy, even in patients with advanced heart disease.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Types of Arrhythmia". NHLBI. July 1, 2011. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Baldzizhar, A; Manuylova, E; Marchenko, R; Kryvalap, Y; Carey, MG (September 2016). "Ventricular Tachycardias: Characteristics and Management.". Critical care nursing clinics of North America. 28 (3): 317–29. PMID 27484660.

- ↑ Neumar, RW; Shuster, M; Callaway, CW; Gent, LM; Atkins, DL; Bhanji, F; Brooks, SC; de Caen, AR; Donnino, MW; Ferrer, JM; Kleinman, ME; Kronick, SL; Lavonas, EJ; Link, MS; Mancini, ME; Morrison, LJ; O'Connor, RE; Samson, RA; Schexnayder, SM; Singletary, EM; Sinz, EH; Travers, AH; Wyckoff, MH; Hazinski, MF (3 November 2015). "Part 1: Executive Summary: 2015 American Heart Association Guidelines Update for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care.". Circulation. 132 (18 Suppl 2): S315–67. PMID 26472989.

In the appendix

- ↑ Wellens HJ, Bär FW, Lie KI (January 1978). "The value of the electrocardiogram in the differential diagnosis of a tachycardia with a widened QRS complex". The American Journal of Medicine. 64 (1): 27–33. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(78)90176-6. PMID 623134.

- ↑ Brugada P, Brugada J, Mont L, Smeets J, Andries EW (May 1991). "A new approach to the differential diagnosis of a regular tachycardia with a wide QRS complex". Circulation. 83 (5): 1649–59. doi:10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1649. PMID 2022022.

- ↑ Baerman JM, Morady F, DiCarlo LA, de Buitleir M (January 1987). "Differentiation of ventricular tachycardia from supraventricular tachycardia with aberration: value of the clinical history". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 16 (1): 40–3. doi:10.1016/S0196-0644(87)80283-4. PMID 3800075.

- ↑ Stewart RB, Bardy GH, Greene HL (June 1986). "Wide complex tachycardia: misdiagnosis and outcome after emergent therapy". Annals of Internal Medicine. 104 (6): 766–71. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-104-6-766. PMID 3706928.

- ↑ John RM, Tedrow UB, Koplan BA, et al. (October 2012). "Ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death". Lancet. 380 (9852): 1520–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61413-5. PMID 23101719.

- ↑ Kasper, D. (2012). The Tachyarrhythmias. In Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (18th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 1892-1893). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Link, MS; Atkins, DL; Passman, RS; Halperin, HR; Samson, RA; White, RD; Cudnik, MT; Berg, MD; Kudenchuk, PJ; Kerber, RE (2 November 2010). "Part 6: electrical therapies: automated external defibrillators, defibrillation, cardioversion, and pacing: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care.". Circulation. 122 (18 Suppl 3): S706–19. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970954. PMID 20956222.

- 1 2 deSouza, IS; Martindale, JL; Sinert, R (February 2015). "Antidysrhythmic drug therapy for the termination of stable, monomorphic ventricular tachycardia: a systematic review.". Emergency medicine journal : EMJ. 32 (2): 161–167. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-202973. PMID 24042252.

- ↑ Aliot EM, Stevenson WG, Almendral-Garrote JM, et al. (June 2009). "EHRA/HRS Expert Consensus on Catheter Ablation of Ventricular Arrhythmias: developed in a partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a Registered Branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA)". Europace. 11 (6): 771–817. doi:10.1093/europace/eup098. PMID 19443434.

- ↑ Akca, F; Önsesveren, I; Jordaens, L; Szili-Torok, T (June 2012). "Safety and efficacy of the remote magnetic navigation for ablation of ventricular tachycardias--a systematic review.". Journal of interventional cardiac electrophysiology : an international journal of arrhythmias and pacing. 34 (1): 65–71. doi:10.1007/s10840-011-9645-2. PMID 22180126.

- ↑ Wissner E, Stevenson WG, Kuck KH (June 2012). "Catheter ablation of ventricular tachycardia in ischaemic and non-ischaemic cardiomyopathy: where are we today? A clinical review". European Heart Journal. 33 (12): 1440–50. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs007. PMID 22411192.