Lucius Artorius Castus

Lucius Artorius Castus (fl. mid-late 2nd century AD or early to mid-3rd century AD) was a Roman military commander. A member of the gens Artoria (possibly of Messapic[1][2][3] or Etruscan origin[4][5][6]), he has been suggested as a potential historical basis for King Arthur.

Military career according to sources

What is known of Artorius comes from inscriptions on fragments of a sarcophagus, and a memorial plaque, found in Podstrana, on the Dalmatian coast in Croatia. Although the inscriptions cannot be precisely dated, Lucius Artorius Castus probably served in the Roman army some time between the mid-late 2nd century AD[7] or early to mid-3rd century AD.[8][9]

The first inscription

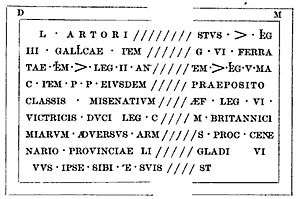

The sarcophagus inscription, which was broken into two pieces at some point prior to the 19th century and set into the wall of the Church of St Martin in Podstrana Croatia, reads (note that "7" is a rendering of the symbol used by scribes to represent the word centurio; ligatured letters are indicated with underlines):

D...............................M L ARTORI[.........]STVS 7 LEG III GALLICAE ITE[....]G VI FERRA TAE ITEM 7 LEG II AD[....]TEM 7 LEG V M C ITEM P P EIVSDEM [...] PRAEPOSITO CLASSIS MISENATIVM [..]AEFF LEG VI VICTRICIS DVCI LEGG [...]M BRITANICI MIARVM ADVERSVS ARM[....]S PROC CENTE NARIO PROVINCIAE LI[....] GLADI VI VVS IPSE SIBI ET SVIS [....]ST[...]

Manfred Clauss of the Epigraphik-Datenbank Clauss-Slaby (EDCS), following the readings and expansions provided in CIL 03, 01919; CIL 03, 08513; CIL 03, 12813; Dessau 2770; IDRE-02, 303, expands the text as:

- D(is) [M(anibus)] | L(ucius) Artori[us Ca]stus |(centurio) leg(ionis) | III Gallicae item [|(centurio) le]g(ionis) VI Ferratae item |(centurio) leg(ionis) II Adi[utr(icis) i]tem |(centurio) leg(ionis) V M[a]c(edonicae) item p(rimus) p(ilus) eiusdem praeposito classis Misenatium [pr]aef(ectus) leg(ionis) VI Victricis duci legg(ionum) [triu]m Britan(n)ic{i}{mi}arum adversus Arme[nio]s proc(urator) centenario(!) provinciae Li[burniae iure] gladi(i) vivus ipse sibi et suis [...ex te]st(amento)

Hans-Georg Pflaum offered[10] a slightly different expansion:

- D(is) M(anibus) L(ucius) Artori[us Ca]stus (centurio) leg(ionis) III Gallicae item [(centurio) le]g(ionis) VI Ferratae item (centurio) leg(ionis) II Adi[utricis i]tem (centurio) V M(acedonicae) C(onstantis) item p(rimi) p(ilus) eiusdem [legionis], praeposito classis Misenatium, [item pr]aeff(ecto) leg(ionis) VI Victricis, duci legg(ionum) [duaru]m Britanicimiarum adversus Arm[oricano]s, proc[uratori) centenario provinciae Lib[urn(iae) iure] gladi vivus ipse et suis [….ex te]st(amento)

Anthony Birley translates[11] this as:

- "To the divine shades, Lucius Artorius Castus, centurion of the Third Legion Gallica, also centurion of the Sixth Legion Ferrata, also centurion of the Second Legion Adiutrix, also centurion of the Fifth Legion Macedonica, also chief centurion of the same legion, in charge of (Praepositus) the Misenum fleet, prefect* of the Sixth Legion Victrix, commander of two** British legions against the Armenians, centenary procurator of Liburnia with the power of the sword. He himself (set this up) for himself and his family in his lifetime.***"

*Note that the double -ff- in PRAEFF should be indicative of the plural (often dual), though it might be a scribal error here.[12]

**Birley follows Pflaum's expansion of the text where [duaru]m "of two" is reinstated before Britanicimiarum.[11] Previous editors have preferred to restore the word as alarum "to/for the alae", which may make better sense if duci legg is to be understood as the title dux legionum.

***Birley does not translate the final phrase, [...ex te]st(amento), which (if correct) should be rendered "...according to the terms of (his) will"[13]

As of 2009, the two stone fragments bearing this inscription have been removed from the wall of the Church of St. Martin for scientific analysis and restoration; they have since been replaced by a copy.

The second inscription

The memorial plaque, which was discovered not far away from the first inscription and was also broken at some point prior to the 19th century, reads:

L ARTORIVS CASTVS P P LEG V MA[.] PR AEFEC[.]VS LEG VI VICTRIC [.....]

Which Clauss (following CIL 03, 12791 (p 2258, 2328,120); CIL 03, 14224; IDRE-02, 304), expands:

L(ucius) Artorius | Castus p(rimus) p(ilus) | leg(ionis) V Ma[c(edonicae)] pr|aefec[t]us leg(ionis) | VI Victric(is)|[...]

Translated:

Lucius Artorius Castus, Primus Pilus of the legion V Macedonica, Prefect of the Legion VI Victrix [....]

A third inscription?

An undated, unprovenanced inscription on a stamp, supposedly discovered in Rome but recorded as being in Paris in the 19th century [14] reads:

• LVCI •

• ARTORI

• CASTI •

Without further information on the inscription, we cannot say whether or not it refers to our Lucius Artorius Castus, or simply another man of the same name.

Units and ranks mentioned

Centurio of Legio III Gallica

The first unit mentioned on Artorius' inscription is the legio III Gallica - for most of the 2nd and 3rd centuries the unit was stationed in Syria. Artorius held the rank of centurion in this legion - most Roman soldiers only achieved the rank of centurion after about 15–20 years of service, but it was not unknown for some politically connected civilians of the equestrian class to be directly commissioned as centurions upon entering the Army, though these equestrian centurions (known as "ex equite Romano") were in the minority.[15] We cannot tell whether or not Artorius had a lengthy career as a legionary soldier before attaining the centurionate, or whether he was directly commissioned at this rank, as the vast majority of career centurion's inscriptions do not mention any ranks that they might have held below the centurionate.[16] Successful officers often omitted the record of any ranks lower than primus pilus,[16][17] as Artorius did on his memorial plaque.

Centurio of Legio VI Ferrata

From the middle of the 2nd century until at least the early 3rd century the legio VI Ferrata was stationed in Judea.

Centurio of Legio II Adiutrix

From the early 2nd century onward the legio II Adiutrix were based at Aquincum (modern Budapest) and took part in several notable campaigns against the Parthians, Marcomanni, Quadi and, in the mid-3rd century, the Sassanid empire.

Centurio and Primus Pilus of Legio V Macedonica

The legio V Macedonica was based in Roman Dacia throughout the 2nd century and through most of the 3rd - the unit took part in battles against the Marcomanni, Sarmatians and Quadi; it was while serving in this unit that Artorius achieved the rank of primus pilus.

Praepositus of the Misenum fleet

Artorius next acted as Provost (Praepositus) of the Misenum fleet in Italy. This title (generally given to Equites) indicated a special command over a body of troops, but somewhat limited in action and subject to the Emperor's control.[18]

Praefectus of Legio VI Victrix

The Legio VI Victrix was based in Britain from c. 122 AD onward, though their history during the 3rd century AD is rather hazy. Throughout the 2nd century AD and into the 3rd, the headquarters of the VI Victrix was at Eboracum (modern York). The unit was removed briefly to Lugdunum (Lyons) in 196 AD by Clodius Albinus, during his doomed revolt against the emperor Severus, but returned to York after the revolt was quelled - and the unit suffered a significant defeat - in 197 AD.

Artorius' position in the Legio VI Victrix, Prefect of the Legion (Praefectus Legionis), was equivalent to that of the Praefectus Castrorum.[19] Men who had achieved this title were normally 50–60 years old and had been in the army most of their lives, working their way up through the lower ranks and the centurionate until they reached Primus Pilus[20] (the rank seems to have been held exclusively by primipilares[21] ). They acted as third-in-command to the legionary commander, the Legatus legionis, and senior tribune and could assume command in their absence.[19][20] Their day-to-day duties included maintenance of the fortress and management of the food supplies, sanitation, munitions, equipment, etc.[20][22] For most who had attained this rank, it would be their last before retirement.[22] During battles, the Praefectus Castrorum normally remained at the unit's home base with the reserve troops,[23] so, given his administrative position and (probably) advanced age, it is unlikely that Artorius actually fought in any battles while serving in Britain.

Artorius could have overseen vexillations of troops guarding Hadrian's Wall, but his inscriptions do not provide us with any precise information on where he might have served while in Britain. It has been suggested by the author Linda Malcor that he was stationed at Bremetennacum with a contingent of Sarmatians (originally sent to Britain in 175 AD) by emperor Marcus Aurelius,[24] but there is no evidence to support such a conjecture. Given his duties as Praefectus Legionis, it is reasonable to assume that he spent some - if not all - of his time in Britain at the VI Victrix's headquarters in York.

It is interesting that the title is spelled (P)RAEFF on Artorius' sarcophagus - doubled letters at the end of abbreviated words on Latin inscriptions usually indicated the plural (often dual) and some legions are known to have had multiple praefecti castrorum.[20][22] The title is given in the singular on the memorial plaque, though, so we might have a scribal error on the sarcophagus. If not, then Artorius was probably one of two prefects of this legion.

Dux Legionum of the Alae(?) "Britanicimiae"

Before finishing his military career, Artorius lead an expedition of some note as a Dux Legionum, a temporary title accorded to officers who were acting in a capacity above their rank, either in command of a collection of troops (generally combined vexillations drawn from legions[25]) in transit from one station to another or in command of a complete unit (the former seems to be the case with Artorius, since the units are spoken of in the genitive plural).[26]

Adversus *Arm[oric(an)o]s or Adversus *Arme[nio]s?

For many years it has been believed that Artorius' expedition was against the Armoricans (based on the reading ADVERSUS ARM[....]S, reconstructed as "adversus *Armorcianos" - "against the Armoricans" - by Theodor Mommsen in the CIL and followed by most subsequent editors of the inscription), but the earliest published reading of the inscription, made by the Croatian archaeologist Francesco Carrara(Italian) in 1850, was ADVERSUS ARME[....],[27] with a ligatured ME (no longer visible on the stone, possibly due to weathering, since the stone has been exposed to the elements for centuries and was reused as part of a roadside wall next to the church of St. Martin in Podstrana; the mutilated word falls along the broken right-hand edge of the first fragment of the inscription). If Carrara's reading is correct, the phrase is most likely to be reconstructed as "adversus *Armenios", i.e. "against the Armenians", since no other national or tribal name beginning with the letters *Arme- is known from this time period.[28]

It should be noted that the regional names Armoricani or Armorici are not attested in any other Latin inscriptions, whereas the country Armenia and derivatives such as the ethnic name Armenii and personal name Armeniacus are attested in numerous Latin inscriptions. Furthermore, no classical sources mention any military action taken against the Armorici/Armoricani (which was in origin a regional name that encompassed a number of different tribes) in the 2nd or 3rd centuries. While there are literary references to (and a small amount of archaeological evidence for) minor unrest in northwestern Gaul during this time period[29] - often referred to as, or associated with, the rebellion of the Bagaudae, there is no evidence that the Bagaudae were connected with the Armorici/Armoricani, or any other particular tribe or region for that matter, making the possible reference to the Armorici/Armoricani somewhat strange (especially since Armorica was otherwise experience a period of prosperity in the late 2nd century AD[30] (when Malcor, et al. believe that Artorius' expedition took place). Armenia, on the other hand, was the location of several conflicts involving the Romans during the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The alternate, "Armenian" translation was put forward as early as 1881 by the epigrapher and classical scholar Emil Hübner and most recently taken up again by the historian and epigrapher Xavier Loriot, who (based on the contextual and epigraphic evidence) suggests a floruit for Artorius in the early mid-3rd century AD[28] (Loriot's analysis of the inscription has recently been adopted by the Roman historians Anthony Birley[11] and Marie-Henriette Quet).[31]

Britanicimiae

The name of the units that Artorius led in this expedition, "Britanicimiae", seems to be corrupt - it might be reconstructed as *Britanniciniae or *Britannicianiae. If so, they were probably units similar in nature to the ala and cohors I Britannica (also known as the I Flavia Britannica or Britanniciana, among other titles), which were stationed in Britain in the mid-1st century AD, but removed to Vindobona in Pannonia by the late 80s AD (they would later take part in Trajan's Parthian War of 114-117 AD and Trebonianus Gallus' Persian war of 252 AD).[32] Though the name of the unit was derived from its early service in Britain, the unit was not generally composed of ethnic Britons.[33][34] No units of this name are believed to have been active in Britain during the late 2nd century.[33] In an inscription from Sirmium in Pannonia dating to the reign of the emperor Gallienus (CIL 3, 3228), we have mention of vexillations of legions *Britan(n)icin([i?]ae) ("militum vexill(ationum) legg(ionum) ]G]ermaniciana[r(um)] [e]t Brittan(n)icin(arum)") - another form that is very similar to the *Britan(n)ici{m}iae from Artorius' inscription.

Procurator Centenarius of Liburnia

Exceptionally talented, experienced and/or connected Praefects Castrorum/Legionis could sometimes move on to higher civilian positions such as Procurator,[20] which Artorius indeed managed to accomplish after retiring from the army. He became procurator centenarius (governor) of Liburnia, a part of Roman Dalmatia, today's Croatia. (centenarius indicates that he received a salary of 100,000 sesterces per year). Nothing further is known of him. Other Artorii are attested in the area, but it is unknown if Lucius Artorius Castus started this branch of the family in Dalmatia, or whether the family had already been settled there prior to his birth (if the latter, Artorius might have received the Liburnian procuratorship because he was a native of the region).

The date of Lucius Artorius Castus's floruit

No dates are given in either inscription, making it difficult to offer a precise date for them, no less Lucius Artorius Castus's floruit. The late French epigraphy expert Xavier Loriot suggested that Lucius Artorius Castus's expedition against the Armenians (as he reads the main inscription) could have taken place in 215 AD, under the reign of emperor Caracalla, or perhaps later, in 232 AD, under the reign of Severus Alexander (when P. Aelius Hammonius led a Cappadocian force in Severus’s Persian war).[35] Three Croatian archaeologists examined the inscriptions in 2012, as part of an international conference on Lucius Artorius Castus organized by authors Linda Malcor and John Matthews: Nenad Cambi, Željko Miletić, and Miroslav Glavičić. Cambi proposes that Lucius Artorius Castus' career can be dated to the late 2nd century AD and his death to the late 2nd, or perhaps early 3rd century AD. Glavičić dates Lucius Artorius Castus's military career to the middle- through late-2nd century AD and proposes that he was the first governor of the province of Liburnia, which Glavičić suggests was only established as a separate province from Dalmatia circa 184-185 AD. Miletić dates Lucius Artorius Castus's military career to circa 121-166 AD and his procuratorship of the province of Liburnia to circa 167-174 AD. Cambi, Miletić, and Glavičić all accept the reading (adversus) Armenios, "against the Armenians" (with Cambi offering Armorios [an abbreviation of Armoric[an]os] as an alternate possibility); Miletić places the expedition against the Armenians during emperor Lucius Verus's Armenian and Parthian war of 161-166 AD.[36][37][38]

Identification with King Arthur

In 1924, Kemp Malone was the first to suggest the possibility that Lucius Artorius Castus was the inspiration for the figure of Arthur in medieval European literature. More recent champions have included authors C. Scott Littleton and Linda Malcor. As a research consultant for the film King Arthur (2004), Malcor's hypotheses regarding Artorius were the primary inspiration for the screenplay.[39]

The careers of the historical Artorius and the traditional King Arthur do have certain differences. For example, Artorius was not contemporaneous with the Saxon invasions of Britain in the 5th century CE. The possibility, however remote, is nonetheless real that Artorius was remembered in local tales and legends that grew in the retelling. No definitive proof, however, has yet been established that Lucius Artorius Castus was the "real" King Arthur.

| Lucius Artorius Castus | King Arthur | |

|---|---|---|

| Floruit | Unknown; probably late 2nd or early 3rd century CE. | Traditionally assigned to the late 5th or early 6th century CE. |

| Name | Artorius = LAC's family name, his nomen gentile. | Arthur is potentially derived from Latin Artorius, but a Celtic origin is also possible. Treated as a native Welsh first name in medieval Latin texts (where it is always rendered as Art[h]ur[i]us and never as Artorius). |

| Ethnicity | The Artorii family have roots in Italy, potentially of Messapic or Etruscan origin; LAC might have been born to a branch of the family that settled in Dalmatia. | Traditionally linked in Welsh literature and genealogies to the British nobility of Cornwall. |

| Religion | Unknown; dedications to the Di Manes, as found on LAC's tomb, are found in both pagan and Christian inscriptions in the 3rd century CE. | At the very least, nominally Christian - according to the Historia Brittonum he bore an image of the Blessed Virgin Mary in one of his battles, although later texts depict him as antagonistic towards clergymen. |

| Military Status | High-ranking, career officer in the Roman army; late in his career (likely as an older man), he served as Camp Prefect in Britain, and finally as Dux Legionum ("Leader of Legions") in a single military campaign. | In the medieval Latin of the Historia Brittonum, Arthur is called a miles, "mounted warrior, armed horseman" (a shift in meaning of miles from older Classical Latin, in which the word meant "professional soldier, common soldier, private, low-ranking foot soldier"[40][41][42]). Also, in the Historia Brittonum, Arthur is called dux belli (alternately dux bellorum in some MSS), "leader of the battle(s)" (specifically, the 12 battles that he fought with the aid of the British kings against the Saxons), but this is a conventional Latin phrase and does not indicate that Arthur held the military title of Dux in a Post-Roman British army (in fact, non-Roman war leaders are sometimes called dux belli/bellorum in ancient Latin texts, including the biblical hero Joshua, in the Latin Vulgate Bible). In later medieval Welsh sources he is called both "emperor" and "king" (the latter title preferred in medieval Arthurian Romance). |

| British Battles | During battle, Camp Prefects normally remained at their unit's base with the reserve troops, so it is unlikely that LAC fought while in Britain. LAC later oversaw an expedition of troops with some sort of British connection, either to Gaul or Armenia. | In the 9th century Historia Brittonum, Arthur, along with the British kings, fought 12 battles in Britain against the invading Saxons, and Arthur allegedly slew many hundreds of Saxons by his own hand (the exact number differs in the various manuscripts). In later texts (such as the 11th century Life of St. Goeznovius and the 12th century Historia Regum Britanniae), Arthur is stated to have fought battles in Gaul as well as in Britannia. |

| Death | Unknown date and circumstances; probably died at an advanced age, potentially during his procuratorship of Liburnia (where he was buried). | In Welsh literature, traditionally stated to have died during the Battle of Camlann (of unknown location in Britain); his burial site was unknown to medieval Welsh. |

Lucius Artorius Castus as King Arthur in modern entertainment

In the film King Arthur (2004), Artorius is partially identified with King Arthur. The film asserts that Arthur's Roman name was "Artorius Castus", and that Artorius was an ancestral name derived from that of a famous leader. His floruit ("prime time") is, however, pushed a few centuries later so that he is made a contemporary of the invading Saxons in the 5th century CE. This would be in agreement with native Welsh tradition regarding Arthur, although his activities are placed many decades earlier than the medieval sources assign to him.

Lucius Artorius Castus is the real name of the character Askeladd in the manga Vinland Saga, who is descended from Arthur himself.

In Rome: Total War: Barbarian Invasion, one of the historical battle scenarios features the Battle of Badon Hill with Lucius Artorius Castus as commander of the Romano-British forces.

References

- ↑ Marcella Chelotti, Vincenza Morizio, Marina Silvestrini, Le epigrafi romane di Canosa, Volume 1, Edipuglia srl, 1990, pg. 261, 264.

- ↑ Ciro Santoro, "Per la nuova iscrizione messapica di Oria", La Zagaglia, A. VII, n. 27, 1965, P. 271-293.

- ↑ Ciro Santoro, La Nuova Epigrafe Messapica "IM 4. 16, I-III" di Ostuni ed nomi in Art-, Ricerche e Studi, Volume 12, 1979, p. 45-60

- ↑ Wilhelm Schulze, Zur Geschichte lateinischer Eigennamen (Volume 5, Issue 2 of Abhandlungen der Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften zu Göttingen, Philologisch-Historische Klasse, Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften Göttingen Philologisch-Historische Klasse) , 2nd Edition, Weidmann, 1966, p. 72, pp. 333-338

- ↑ Olli Salomies: Die römischen Vornamen. Studien zur römischen Namengebung. Helsinki 1987, p. 68

- ↑ Herbig, Gust., "Falisca", Glotta, Band II, Göttingen, 1910, p. 98

- ↑ Pflaum, H.-G. Les Carrières procuratoriennes équestres sous le Haut-Empire romain, 3 vols. Paris, Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner, 1960, pp. 535 ff.

- ↑ Ritterling, E. "Legio", RE XII, 1924, col. 106.

- ↑ Gilliam, J. Frank. "The Dux Ripae at Dura", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 72, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941, p. 163.

- ↑ Pflaum, p. 535.

- 1 2 3 Birley, p. 355.

- ↑ Egbert, p. 447.

- ↑ Dixon, Southern, p. 240.

- ↑ CIL XV (Inscriptiones urbis Romae Latinae: instrumentum domesticum, Heinrich Dressel,"Signacula Aenea"), #8090, p. 1002.

- ↑ Keppie (1998), p. 179.

- 1 2 Goldsworthy, p. 31, n. 80.

- ↑ Keppie (2000), p. 168.

- ↑ Smith, R. E., "Dux, Praepositus", Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, Bd. 36 (1979), pp. 263-278

- 1 2 Mommsen, Demandt, Demandt, p. 311.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Webster, p. 113.

- ↑ Dobson, p. 415.

- 1 2 3 Keppie (1998), p. 177.

- ↑ Smith, Wayte, Marindin, p. 798.

- ↑ Littleton and Malcor, p. 63.

- ↑ Breeze, Dobson, p. 180.

- ↑ Southern, Dixon, p. 59.

- ↑ Carrara, p. 23.

- 1 2 Loriot, pp. 85-86.

- ↑ Galliou, Jones, p. 118.

- ↑ Galliou, Jones, p. 117-118.

- ↑ Quet, p. 339.

- ↑ Tully, pp. 379-380.

- 1 2 Kennedy, pp. 249-255.

- ↑ Tully, pp. 380.

- ↑ Loriot, Xavier, "Un mythe historiographique : l'expédition d'Artorius Castus contre les Armoricains", Bulletin de la société Nationale des Antiquaires de France, 1997, pp. 85–87.

- ↑ Cambi, Nenad, "Lucije Artorije Kast: njegovi grobišni areal i sarkofag u Podstrani (Sveti Martin) kod Splita", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30th of March to 2nd of April 2012, Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 29-40.

- ↑ Miletić, Željko, "Lucius Artorius Castus i Liburnia", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30th of March to 2nd of April 2012, Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 111-130.

- ↑ Glavičić, Miroslav , "Artorii u Rimskoj Provinciji Dalmaciji", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30th of March to 2nd of April 2012, Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 59-70.

- ↑ Matthews, John, "An Interview with David Franzoni", in: Arthuriana, Volume 14, Number 3, Fall 2004,pp. 115-120

- ↑ D'A. J. D. Boulton, "Classic Knighthood as Nobiliary Dignity", in: Stephen Church, Ruth Harvey (ed.), Medieval knighthood V: papers from the sixth Strawberry Hill Conference 1994, Boydell & Brewer, 1995, pp. 41-100.

- ↑ Frank Anthony Carl Mantello, A. G. Rigg, Medieval Latin: an introduction and bibliographical guide, UA Press, 1996, p. 448.

- ↑ Charlton Thomas Lewis, An elementary Latin dictionary, Harper & Brothers, 1899, p. 505.

Bibliography

- Birley, Anthony, The Roman Government of Britain, Oxford, 2005, p. 355

- Breeze, David John, Dobson, Brian, Roman Officers and Frontiers, Franz Steiner Verlag, 1993, p. 180

- Cambi, Nenad, "Lucije Artorije Kast: njegovi grobišni areal i sarkofag u Podstrani (Sveti Martin) kod Splita", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30 March to 2 April 2012 / Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 29–40.

- Carrara, Francesco, De scavi di Salona nel 1850, Abhandlung der koeniglichen Boehmischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften, 5 s, 7, 1851/1852, p. 23

- Dessau, Hermann, Inscriptiones Latinae Selectae, Berlin 1892-1916 (Dessau 2770)

- Dobson, B., "The Significance of the Centurion and 'Primipilaris' in the Roman Army and Administration," Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt II.1 Berlin/NY 1974 392- 434.

- Dixon, Karen R., Southern, Pat, The Roman cavalry: from the first to the third century AD, Routledge, London, 1997, p. 240

- Egbert, James Chidester, Introduction to the study of Latin inscriptions, American Book Company, New York, 1896, p. 447

- Galliou, Patrick, Jones, Michael, The Bretons, Blackwell, Oxford (UK)/Cambridge (MA), 1991

- Gilliam, J. Frank. "The Dux Ripae at Dura", Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 72, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1941, p. 163

- Glavičić, Miroslav, "Artorii u Rimskoj Provinciji Dalmaciji", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30 March to 2 April 2012 / Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 59–70.

- Goldsworthy, Adrian Keith, The Roman army at war: 100 BC-AD 200, Oxford University Press, 1998

- Haverfield, Francis, The Romanization of Roman Britain, Oxford, 1912, p. 65

- Hübner, Emil, "Exercitus Britannicus", Hermes XVI, 1881, p. 521ff.

- Jackson, Thomas Graham, Dalmatia, the Quarnero and Istria, Volume 2, Oxford, 1887, pp. 166–7

- Kennedy, David, "The 'ala I' and 'cohors I Britannica'", Britannia, Vol. 8 (1977), pp. 249–255

- Keppie, Lawrence, The Making of the Roman Army: from Republic to Empire, University of Oklahoma Press, 1998, pp. 176–179

- Keppie, Lawrence, Legions and veterans: Roman army papers 1971-2000, Franz Steiner Verlag, 2000, p. 168.

- Klebs, Elimar, Dessau, Hermann, Prosopographia imperii romani saec. I. II. III, Deutsche Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin, p. 155

- Littleton, C. Scott, Malcor, Linda, From Scythia to Camelot: A Radical Reassessment of the Legends of King Arthur, the Knights of the Round Table and the Holy Grail, New York, Garland, 2000

- Loriot, Xavier, "Un mythe historiographique : l'expédition d'Artorius Castus contre les Armoricains", Bulletin de la Société nationale des antiquaires de France, 1997, pp. 85–86

- Malcor, Linda, "Lucius Artorius Castus, Part 1: An Officer and an Equestrian" Heroic Age, 1, 1999

- Malcor, Linda, "Lucius Artorius Castus, Part 2: The Battles in Britain" Heroic Age 2, 1999

- Malone, Kemp, "Artorius," Modern Philology 23 (1924–1925): 367-74

- Medini, Julian, Provincija Liburnija, Diadora, v. 9, 1980, pp. 363–436

- Miletić, Željko, "Lucius Artorius Castus i Liburnia", in: N. Cambi, J. Matthews (eds.), Lucius Artorius Castus and the King Arthur Legend: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference from 30 March to 2 April 2012 / Cambi, Nenad; Matthews, John (eds.). Split : Književni krug Split, 2014, pp. 111–130.

- Mommsen, Theodor (ed.), Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), vol. III, no. 1919 (p 1030, 2328,120); no. 8513; no. 12813; no. 12791 (p 2258, 2328,120); no. 14224

- Mommsen, Theodor, Demandt, Barbara, Demandt, Alexander, A history of Rome under the emperors, Routledge, London & New York, 1999 (new edition), pp. 311–312

- Peachin, Michael, Iudex vice Caesaris: deputy emperors and the administration of justice during the Principate, Volume 21 of Heidelberger althistorische Beiträge und epigraphische Studien, F. Steiner, 1996, p. 231

- Petolescu, C.C., Inscriptiones Daciae Romanae. Inscriptiones extra fines Daciae repertae, Bukarest 1996 (IDRE-02)

- Pflaum, Hans-Georg, Les carrières procuratoriennes équestres sous le Haut-Empire romain, Paris, 1960, p. 535

- Quet, Marie-Henriette, La "crise" de l'Empire romain de Marc Aurèle à Constantin, Paris, 2006, p. 339

- Ritterling, E. "Legio", RE XII, 1924, col. 106.

- Smith, William, Wayte, William, Marindin, George Eden (eds.), A dictionary of Greek and Roman antiquities, Volume 1, Edition 3, John Murray, London, 1890, p. 798

- Southern, Pat, Dixon, Karen R., The Late Roman Army, Routledge, London, 1996, p. 59

- Tully, Geoffrey D., "A Fragment of a Military Diploma for Pannonia Found in Northern England?", Britannia, Vol. 36 (2005), pp. 375–82

- Webster, Graham, The Roman Imperial Army of the first and second centuries A.D., University of Oklahoma Press, edition 3, 1998, pp. 112–114

- Wilkes, J. J., Dalmatia, Volume 2 of History of the provinces of the Roman Empire, Harvard University Press, 1969, pp. 328–9

External links

- Linda A. Malcor's 1999 article about Lucius Artorius Castus in The Heroic Age, part 1 and part 2

- Photograph of the first sarcophagus fragment from Podstrana

- Photograph of the second sarcophagus fragment from Podstrana

- Photograph of the Church of St. Martin in Podstrana, with the first sarcopahgus fragment in the wall, to the left

- The Lucius Artorius Castus Inscriptions: A Sourcebook