Integrative neuroscience

Integrative neuroscience sculptures a theoretical neuroscience with a mathematical neuroscience that is different from computational neuroscience.[1] In computational neuroscience, reductionist approaches span multiple levels of neural organization.[2] However in integrative neuroscience, each level is seamlessly sculptured as part of a continuum of levels.

The roots of integrative neuroscience originated from the Rashevsky-Rosen school of relational biology[3] that characterizes functional organization mathematically by abstracting away the structure (i.e., physics and chemistry). It was further expanded by Chauvet[4] who introduced hierarchical and functional integration.

Hierarchical integration is structural involving spatiotemporal dynamic continuity in Euclidean space to bring about functional organization, viz.

- Hierarchical organization + Hierarchical integration = Functional organization

However, functional integration is relational and as such this requires a topology not restricted to Euclidean space, but rather occupying vector spaces[5] This means that for any given functional organization the methods of functional analysis enable a relational organization to be mapped by the functional integration, viz.

- Functional organization + Functional integration = Relational Organization

Thus hierarchical and functional integration entails a "neurobiology of cognitive semantics" where hierarchical organization is associated with the neurobiology and relational organization is associated with the cognitive semantics. Relational organization throws away the matter; "function dictates structure", hence material aspects are entailed, while in reductionism the causal nexus between structure and dynamics entails function that obviates functional integration because the causal entailment in the brain of hierarchical integration is absent from the structure.

If integrative neuroscience is studied from the viewpoint of functional organization of hierarchical levels then it is defined as causal entailment in the brain of hierarchical integration. If it is studied from the viewpoint of relational organization then it is defined as semantic entailment in the brain of functional integration.

It aims to present studies of functional organization of particular brain systems across scale through hierarchical integration leading to species-typical behaviors under normal and pathological states. As such, integrative neuroscience aims for a unified understanding of brain function across scale.

Spivey’s continuity of mind thesis [6] extends integrative neuroscience to the domain of continuity psychology.

Motivation

Since the ‘decade of the brain’ there has been an explosion of insights into the brain and their application in most areas of medicine. With this explosion, the need for integration of data across studies, modalities and levels of understanding is increasingly recognized. A concrete exemplar of the value of large-scale data sharing has been provided by the Human Brain Project.

The importance of large-scale integration of brain information for new approaches to medicine has been recognized.[7] Rather than relying mainly on symptom information, a combination of brain and gene information may ultimately be required for understanding what treatment is best suited to which individual person.

It provides a framework for linking the great diversity of specializations within contemporary neuroscience, including

- Molecular neuroscience — genetic and cellular aspects of brain function

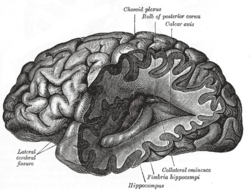

- Neuroanatomy — connections, networks, neurotransmitter systems

- Behavioral neuroscience — the overt consequences of neural activity

- Systems neuroscience — description of sensory and motors systems

- Developmental neuroscience — structural and functional changes during maturation

- Cognitive neuroscience — channels and stages of sensory processing, including memory

- Mathematical neuroscience — quantitative simulation and emulation of neuronal and brain function

- Clinical observations — evidence that can be gleaned from brain dysfunction

This diversity is inevitable, yet has arguably created a void: neglect of the primary role of the nervous system in enabling the animal to survive and prosper. Integrative neuroscience aims to fill this perceived void.

Evolutionary basis

Integrative neuroscience draws on the important context of our evolutionary history Charles Darwin.[8]

References

- ↑ Poznanski, RR (2000). Biophysical Neural Networks: Foundations of Integrative Neuroscience. New York [New York]: Mary Ann Liebert.

- ↑ Grillner, S.; Kozlov, A.; Kotaleski, J.H. (2005). "Integrative neuroscience: linking levels of analyses". Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 15 (5): 614–621. doi:10.1016/j.conb.2005.08.017.

- ↑ Louie,AH (2009). More Than Life Itself: A Synthetic Continuation in Relational Biology. Frankfurt [Germany]: Ontos Verlag.

- ↑ Chauvet, Gilbert (1996). Theoretical Systems in Biology: Hierarchal and Functional Integration. Oxford [United Kingdom]: Pergamon Press.

- ↑ Brzychczy,S.; Poznanski, RR (2013). Mathematical Neuroscience. Amsterdam [The Netherlands]: Elsevier BV.

- ↑ Spivey, M.J. (2007). The Continuity of the Mind. New York [New York]: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Insel, Thomas R; Volkow, Nora D; Landis, Story C; Li, Ting-Kai; Battey, James F; Sieving, Paul (2003). "Limits to growth: why neuroscience needs large-scale science". Nature Neuroscience. 7 (5): 426–427. doi:10.1038/nn0504-426. Retrieved 25 September 2011.

- ↑ Barrett, Paul (1980). Metaphysics, Materialism, & the Evolution of Mind:the early writings of Charles Darwin. Chicago: Chicago University Press. ISBN 0-226-13659-0.