Iglesias, Sardinia

| Iglesias | |

|---|---|

| Comune | |

| Comune di Iglesias | |

|

the Cathedral | |

Iglesias Location of Iglesias in Sardinia | |

| Coordinates: 39°19′N 8°32′E / 39.317°N 8.533°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Region | Sardinia |

| Province / Metropolitan city | South Sardinia |

| Frazioni | Barega, Bindua, Corongiu, Masua, Monte Agruxiau, Monteponi, Nebida, San Benedetto, San Giovanni Miniera, Tanì |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Emilio Agostino Gariazzo |

| Area | |

| • Total | 207.63 km2 (80.17 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 200 m (700 ft) |

| Population (30 September 2012)[1] | |

| • Total | 27,552 |

| • Density | 130/km2 (340/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Iglesienti |

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) |

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) |

| Postal code | 09016 |

| Dialing code | 0781 |

| Patron saint | Santa Chiara |

| Saint day | 11 August |

| Website | Official website |

Iglesias (pronounced [iˈɡlɛːzjas] or locally [iˈɡlezjas]; Sardinian: Igrèsias)[2] ![]() listen is a comune and city of the province of South Sardinia, region of Sardinia, Italy. It was the co-capital of the ex province of Carbonia-Iglesias (along with Carbonia) as well as its second-largest community.

listen is a comune and city of the province of South Sardinia, region of Sardinia, Italy. It was the co-capital of the ex province of Carbonia-Iglesias (along with Carbonia) as well as its second-largest community.

In the period of Spanish control, the city was one of the most important royal cities of Sardinia. It is also episcopal seat (Roman Catholic Diocese of Iglesias). Situated at an elevation of 190 metres (620 ft) in the hills in the southwest of Sardinia, it was a centre of a mining district where lead, zinc, and silver were extracted. It was also a centre for the distillation of sulfuric acid.

History

Prehistory and ancient History

The area where today stands the city of Iglesias was already inhabited in prehistoric times: the oldest traces of human settlement date back to the Neolithic. To the Ozieri culture (fourth millennium BC) date the domus de Janas discovered in the mountainous area of San Benedetto. Also belong to the prenuragic period finds found in nearby caves attributable to the cultures of Monte Claro, Bell Beaker and Bonnanaro.[3] Follow further traces of Nuragic, Punic and Roman presences. The ancient sources speak of a city called Metalla, perhaps located along the border with Fluminimaggiore.

Medieval history

From ninth century, after a period of human absence, there was a little urban centre proved by the presence of a Byzantine church (Church of San Salvatore). After, when Byzantine left the island, the territory, called Cixerri, was under Giudicato of Cagliari's control. In the 1258, after the fall of the Giudicato, its south-west portion (curatorie of Cixerri and Sulcis) was assigned to the pisan Della Gherardesca family. The Cixerri part was under the count Ugolino Della Gherardesca's control.[4] The count decided to take advantage of the silver resources present in the zone, so he founded a new city, called in Latin "Villa Ecclesiae" (or Villa di Chiesa, Church's Villa), developing the old structures and building new ones. Della Gherardesca family also fashioned the medieval Castle of Salvaterra, the defence walls, athe hospital and an aqueduct.

After the death of count Ugolino in March 1289 in the Tower of Muda in Pisa, where he had been imprisoned in the summer of 1288 because of the charge of sedition and treason, its Sardinian possessions in the Cixerri were inherited by his son, Guelfo della Gherardesca; escaped from the authority of Pisa in 1288, he had settled in Villa di Chiesa.[5] Guelfo pursued a policy of hostility towards the central power of the republic and tried to seize by force the "sixth" of the former Giudicato of Cagliari (Sulcis) owned by the heirs of Gherardo della Gherardesca, occupying the castle of Gioiosa Guardia of Villamassargia. Pisa's response was swift and in 1295 the troops of the republic supported by the forces of Marianus II of Arborea, attacked Villa di Chiesa. Guelfo was wounded by a "verga sardesca" near Domusnovas and then tried to escape to Sassari but died due to an infection in the hospital of Siete Fuentes. Villa di Chiesa was administered for a short period by Arborea and then go under the firm control of the town of Pisa between 1301 and 1302.[5]

At the time of the direct domination of Pisa, Villa di Chiesa had already become one of the most important and populous cities of Sardinia, thanks to the strong impetus given to the extraction of lead and silver; it is estimated that at the beginning of the fourteenth century the mines of Villa di Chiesa produced about 10% of the silver in circulation in Europe.[6] The city, populated mostly by Sardinians and Pisans, also housed other communities from the rest of Tuscany and the Italian peninsula, from Corsica[7] and from the German area. The law was regulated by the Breve di Villa di Chiesa, the oldest code of laws of the city, existing in a copy of the 1327 perfectly preserved and kept at the Municipal Historical Archives. An important mint was established in the city.

Conquered by the Aragonese in February 7, 1324 after a siege that lasted more than seven months, Villa di Chiesa was the first Sardinian city to fall to the Iberian domain and the first city of the newborn Kingdom of Sardinia to obtain recognition of a royal city in June 1327. It's during the Aragonese period that the city's name switched from Villa di Chiesa to Iglesias.

During this phase of transition from Pisa to Aragon there were about 6000–7000 persons living in Villa di Chiesa but the Black Plague of 1348 caused the death of many inhabitants.[8]

Towards the end of 1353 the Ecclesienti revolted against the Aragon government and took the side of Marianus IV of Arborea, who had begun hostilities against the Crown of Aragon. After the peace of Sanluri of 1355 the city returned in Aragonese hands but in 1365, with the resumption of the conflict between the giudicato of Arborea and the kingdom of Sardinia, Villa di Chiesa was recaptured by Marianus. The city remained in the hands of Arborea until 1388 when, following the treaty between Eleanor of Arborea and John I of Aragon, it was returned to the Aragonese. In 1391 the city revolted again against the Aragonese, welcoming within its walls the giudical army led by Brancaleone Doria. It was taken up permanently by the Iberians in the summer of 1409.[9]

In 1436 Alfonso V of Aragon gave the city in fief to Eleonora Carroz for 5000 gold florins, however, already in 1450, after the payment of a ransom, Villa di Chiesa regained the status of royal city.

Modern and contemporary history

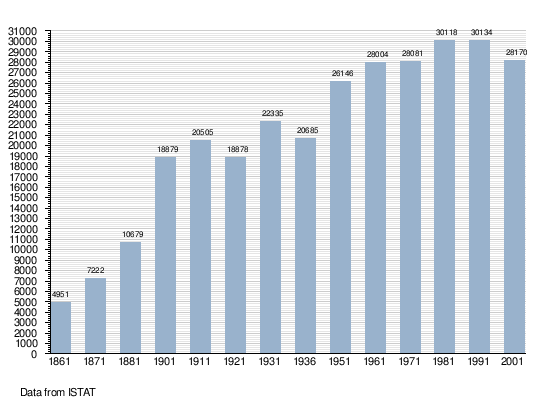

In 1720, after almost 400 years of Aragonese-Spanish rule, the city passed, with the rest of the island, to the House of Savoy. Since the mid-nineteenth century thanks to the reopening of the nearby mines, Iglesias experienced a period of economic, social and cultural renewal. Many miners, workers and technicians from various parts of Sardinia, but also from Northern Italy, settled in this period in the city so that the city population growht from 5,000–6,000 inhabitants in 1850s to about 20,000 in the early twentieth century.

Shortly after the Second World War the Sardinian mining sector was in crisis; the effects of the crisis soon involved the Iglesiente and its mines and the town of Iglesias.

Demographics

As of 31 December 2015, there were 418 foreigners in Iglesias. The largest immigrant group came from Romania, Senegal and China.[10] The population is overwhelmingly Roman Catholic.

Economy

Iglesias in the course of its history experienced ups and downs because of the economy largely focused to mineral resources.

In the 21st century, ceased the mining activity (very few mines continue to survive), Iglesias tries to convert to a touristic town, exploiting the attractions of the Middle Ages. To achieve this goal several initiatives were born such as the medieval parade, tournament of archers, the game of living chess and so on.

Main sights

Castle of Salvaterra

The castle was almost certainly built as part of the urbanization that took place after 1258 under Ugolino della Gheradesca. It was designed as a bulwark from which to survey the town and its surroundings as far as the silver mines.

In 1297 Sardinia and Corsica were made subject to the Crown of Aragon by Pope Boniface VIII but were not actually taken into possession until 1324. The castle of San Guantino changed its name, becoming Salvaterra, and its status: a stone slab from 1325 describes it as castris regalis, a royal castle.

The castle has a square structure; the northern and eastern sides, built in courses of stone alternating with brick, seem to adhere more closely to the original medieval plan, conferring a solidity on the whole structure. It also had a chapel that was dedicated first to San Guantino and later to Sant’Eulalia of Barcelona. The well has been reconstructed in the internal courtyard of the castle

Santa Chiara Cathedral

The construction of the church of Santa Chiara was part of the initiatives aimed at demographic and urban development undertaken by the Donoratico della Gherardesca family.

It is not possible to attribute a single style to the church. Over the centuries it has been transformed several times, whether by the successive dominions or by restoration work (especially the restructuring that began in the nineteenth century). The façade has a pitched roof and is divided into two parts by a moulded cornice that runs horizontally at the level of the architrave over the doorway.

Inside, the church has a large single nave, with six side chapels and a cross-vaulted roof, supported on pillars with carved capitals. The bell tower is noteworthy, housing a bronze bell dating from 1337 by Andrea Pisano; the tower was plastered and the spire added in 1862.

The Museum of Sacred Art is located in the crypt of the Cathedral.

Church of San Francesco

The church has a gabled façade with smooth stonework; the door in the centre of the façade is surmounted by a rose window and flanked by two side oculi. It has a single nave with a wooden ceiling and is divided into seven bays, flanked by seven side chapels; these chapels and the presbytery were added from the sixteenth century onwards.The chapels all have simple cross vaulting meeting in a hanging pendant, except for the fifth chapel on the left, known as the “Crucifix” chapel. The stone choir replaces the original wooden choir which was demolished at the beginning of the 20th century. In addition to the marble font, there are interesting works of art in the chapels on the left, such as the retablo by Antioco Mainas.

The monastery, with the San Francesco Cloisters, was annexed to the church in the 16th century.

Church of Santa Maria di Valverde

The church stands outside the town walls, and is almost contemporary with the Cathedral, with similar style and structure.

Like the cathedral, it follows typical Romanesque style with some Gothic features. The façade underwent successive conservation and restoration works up until the twentieth century. Constructed from pink trachyte ashlars, it is divided into two parts by a horizontal moulded cornice. Inside is a single nave which originally had a lower wooden roof; it terminates in a large square presbytery area which is cross vaulted, with four hanging pendants. The central pendant, larger than the others, depicts the Madonna with Child.

Medieval fortifications

The so-called “Pisan” walls surround the city in correspondence with the historic centre and follow its irregular outline, making the most of the incline with the addition of Salvaterra castle. Although successive urban expansion led to several stretches of the walls being absorbed into private homes, the parts that can still be visited retain the solid, substantial features of medieval military fortifications: a series of blind façades constructed in mixed stones arranged in horizontal courses to create an uneven mass, guaranteeing strong resistance to attack.

Interrupted by 23 towers, the walls could only be passed through the four gateways: Porta Maestra, Porta Castello, Porta Sant'Antonio e Porta Nuova.

Town Hall

The building is in the heart of the historic town centre, in a central position as regards the original medieval perimeter walls. It was built by the Vincenzo Sulcis company between 1871 and 1872, according to plans by civil engineer Antonio Cao Pinna. The façade – set on a base of volcanic stone ashlars – is divided horizontally by string-course cornices. The Council meeting room is very interesting for the decorative additions carried out during the 1920s, designed by Francesco Ciusa, the Sardinian sculptor of international fame, and Remo Branca, the illustrator and painter. The artist Carmelo Floris created a triptych of pictorial panels which decorates the rear walls.

Sanctuary of Madonna delle Grazie

The current building of the Sanctuary of the Virgin delle Grazie dates back to between the 12th and 13th centuries and was initially dedicated to the Cagliari martyr San Saturno. The tastes of the various communitiesthat have modelled the building canbe seen in the façade. In the centre,it is the most ancient style that isevident – approximately 13th century.

Inside the church, there is a single nave divided into six bays by pointed trachyte arches supporting the wooden vault with exposed beams. Some apertures made in the thick outer walls simulate chapels, while two chapels stand out on either side of the presbytery, dedicated on the right to the Sacred Heart of Jesus and on the left to St. Francis.

Mining Art Museum

The Museum was conceived in 1998 by a group of “mining men” who wanted to create a tangible reminder of their origins, in order that the history of their land should not be forgotten.

It is housed in the basement of the “Giorgio Asproni” Mining Institute. On display are some scale model reproductions, newspaper articles about life in the mines and an important collection of period photographs. The museum also contains various types of machinery for the different phases of excavation, drilling and transport, as well as a reconstruction of a mechanical workshop and modern machinery. To reach the tunnels that run underneath the building, it is necessary to go down a ramp along a stretch of iron railway. Here, some of the phases of work in the mines have been reconstructed.

Historical Archive

The archive preserves the history of Villa di Chiesa, the ancient name for the town, from the Catalan-Aragonese, Spanish and Savoy periods. The series of documents begins with Il Breve di Villa di Chiesa, an ancient code of laws dating back to 1327.

It's written on a robust parchment, perhaps, as the text itself suggest, of mutton. Well preserved, only few pages are missing. The text is written in a neat Gothic script, in Pisan dialect.

The Breve is the result of a long process of legislative drafting that began during the period of Donoratico dominion and ended in the period of Aragon dominion. The definitive version, in four books, dates back to the period of direct rule by Pisa over Villa di Chiesa.

Flavia port

This construction holds an important position in terms of innovation and technology in the field of Sardinian mining construction.

The Belgian Vieille Montagne company appointed engineer Cesare Vecelli to carry out a planning study aimed at reducing the costs of transporting ore from the mine to the port. The project was carried out from 1922 to 1924. The construction runs entirely within the mountain for 600 metres (2,000 feet), before exiting high up above the sea. The external structure consists of a façade with a large arch beneath the inscription "Porto Flavia", flanked by a tower. The work consisted of excavating 9 bunkers inside the mountain by enlarging natural caverns. These 9 large rooms develop into two tunnels one on top of the other, directly opposite the islet known as Pan di Zucchero (Sugarloaf).

Monteponi mine

It is difficult to give a date for the first mining activity in this area. We know that Monte Paone was mentioned in 1324, in the will of Baron Berto da San Miniato, a trader from Pisa.

Over the years, th mining concession alternated between the State and private companies, without anyone being able to make it profitable. Poswitive results were finally achieved in 1850, when some entrepreneurs, led by Ligurian Paolo Antonio Nicolay, founded the Monteponi company to carry out mining work underground over thirty years, using the exsting structures. The settlement covers 4 levels and is a genuine worker’s village.

The 2008 project, by architects Herzog & de Meuron, planned to restore the entire industrial area for tourism and cultural purposes.

Coastal territory, bays and beaches

In the littoral zone of the comune of Iglesias (8 kilometres (5.0 miles) from the centre of the city), starting from north to south, there are the following principal beaches:

- "Cala Domestica"

- Shore of "Cala Domestica" with the Spanish tower

- Cavern "Su Forru" ("the oven")

- Shore of "Portu Sciusciau" ("destruct port") with high cliffs (up to 100 metres or 330 ft)

- "Cavern of sea basses"

- Shore "Punta Corr'e Corti" with high cliffs (up to 103 metres or 338 ft)

- Shore "Porto di Canal Grande" ("Big channel port")

- "Sardigna Cavern" (a little cave that shapes the form of Sardinia)

- Shore "Punta Sedda 'e Luas" woth high cliffs (up to 115 metres or 377 ft)

- Shore "Schina 'e Monti Nai" with high cliffs (up to 162 metres or 531 ft)

- Shore "Punta Buccione" or "Punta Buccioni" with high cliffs 167 metres or 548 ft)

- Small island of "Pan di Zucchero" (133 metres (436 feet) high)

- "Porto Bega Sa Canna" (reed's valley port)

- "Masua Port"

- "Masua Beach"

- Shore of Masua

- "Portu Cauli Beach"

- Bay of "Punta Corallo" (coral point)

- Shore of "Portu Ferru"

- Shore of "Portu Bruncu Cobertu"

- The Sea Stak of "Portu Banda": Major stak (36 metres or 118 feet high) and the Minor stak (30 metres or 98 feet high)

- Shore of "Portu Banda"

- Shore of "Porto Ghiano"

- Shore of Nebida

- Small island "S'Agusteri" (35 metres or 115 feet high) (fisherman of Lobsters)

- Shore of Nebida Port

- Bays of "Portu Raffa"

- Shore of "Portu Raffa"

- "Porto Flavia"

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Iglesias is twinned with:

Oberhausen, Germany, since 2002

Oberhausen, Germany, since 2002 Pisa, Italy, since 2009

Pisa, Italy, since 2009

References

- ↑ All demographics and other statistics from the Italian statistical institute (Istat)

- ↑ AA. VV., Dizionario di toponomastica. Storia e significato dei nomi geografici italiani, Milano, GARZANTI, 1996, p. 327

- ↑ La collezione Pistis-Corsi ed il patrimonio archeologico del Comune di Iglesias

- ↑ Casula 1994, p. 291.

- 1 2 Casula 1994, p. 294.

- ↑ Enrico Artifoni, Storia medievale, p.471

- ↑ Tangheroni 1985, p. 226-227-228.

- ↑ Roberto Farinelli,Giovanna Santinucci, I codici minerari nell’Europa preindustriale: archeologia e storia p.46

- ↑ "Il medioevo di Villa di Chiesa appunti di storia e archeologia". Academia.edu.

- ↑ Cittadini Stranieri. Popolazione residente e bilancio demografico al 31 dicembre 2015

Bibliography

- Casula, Francesco Cesare (1994). La Storia di Sardegna. Sassari, it: Carlo Delfino Editore. ISBN 978-88-7138-084-1.

- Tangheroni, Marco (1985). La città dell'argento: Iglesias dalle origini alla fine del Medioevo. Napoli: Liguori Editore.

External links

![]() Media related to Iglesias at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Iglesias at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website (Italian)