History of the Jews in Bulgaria

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| (1,363 (2001 census)[1] - 6,000 Bulgarian citizens of full or partial Jewish descent (according to OJB estimates) Israeli Jews of Bulgarian Descent : 75,000 [2]) | |

| Languages | |

| Hebrew and Bulgarian | |

| Religion | |

| Judaism |

Jews have had a continuous presence in historic Bulgarian lands since before the 2nd century CE, and have often played an important part in the history of Bulgaria.

Today, the majority of Bulgarian Jews live in Israel, while modern-day Bulgaria continues to host a modest Jewish population.

Roman era

Jews are believed to have settled in the region after the Roman conquest. Ruins of "sumptuous"[3] second century synagogues have been unearthed in Philipopolis[4] (now Plovdiv), Nikopol, Ulpia Oescus[5] (modern day Gigen, Pleven Province), and Stobi[6] (now in Macedonia).[3] The earliest written artifact attesting to the presence of a Jewish community in the Roman province of Moesia Inferior is a late 2nd century CE Latin inscription found at Ulpia Oescus bearing a menorah and mentioning archisynagogos. Josephus testifies to the presence of a Jewish population in the city. A decree of Roman Emperor Theodosius I from 379 regarding the persecution of Jews and destruction of synagogues in Illyria and Thrace is also proof of early Jewish settlement in Bulgaria.

Bulgarian Empire

After the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empire and its recognition in 681, a number of Jews suffering persecution in the Byzantine Empire may have settled in Bulgaria. Jews also settled in Nikopol in 967. Some arrived from the Republic of Ragusa and Italy, when merchants from these lands were allowed to trade in the Second Bulgarian Empire by Ivan Asen II. Later, Tsar Ivan Alexander married a Jewish woman, Sarah (renamed Theodora), who had converted to Christianity and had considerable influence in the court. She influenced her spouse to create the Tsardom of Vidin for her son Ivan Shishman, who was also a Jew according to the Matrilineality in Judaism. A church council of 1352 led to the excommunication of heretics and Jews, and three Jews who had been sentenced to death were killed by a mob despite the sentence's having been repealed by the tsar.

The medieval Jewish population of Bulgaria was Romaniote until the 14th-15th century, when Ashkenazim from Hungary (1376) and other parts of Europe began to arrive.

Ottoman rule

By the completion of the Ottoman conquest of the Bulgarian Empire (1396), there were sizable Jewish communities in Vidin, Nikopol, Silistra, Pleven, Sofia, Yambol, Plovdiv (Philippopolis) and Stara Zagora.

In 1470, Ashkenazim banished from Bavaria arrived, and contemporary travellers remarked that Yiddish could often be heard in Sofia. An Ashkenazi prayer book was printed in Saloniki by the rabbi of Sofia in the middle of the 16th century. Beginning in 1494, Sephardic exiles from Spain migrated to Bulgaria via Salonika, Macedonia, Italy, Ragusa, and Bosnia. They settled in pre-existing Jewish population-centres, which were also the major trade centres of Ottoman-ruled Bulgaria. At this point, Sofia was host to three separate Jewish communities: Romaniotes, Ashkenazim and Sephardim. This would continue until 1640, when a single rabbi was appointed for all three groups.

In the 17th century, the ideas of Sabbatai Zevi became popular in Bulgaria, and supporters of his movement, such as Nathan of Gaza and Samuel Primo, were active in Sofia. Jews continued to settle in various parts of the country (including in new trade centres such as Pazardzhik), and were able to expand their economic activities due to the privileges they were given and due to the banishment of many Ragusan merchants who had taken part in the Chiprovtsi Uprising of 1688.

Modern Bulgaria

A modern nation-state of Bulgaria was formed under the terms of the Treaty of Berlin, which ended the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. Under the terms of that treaty, Bulgarian Jews of the new country were granted equal rights. Jews were drafted into the Bulgarian army and fought in the Serbo-Bulgarian War (1885), in the Balkan Wars (1912-13), and in the First World War. 211 Jewish soldiers of the Bulgarian army were recorded as having died during World War I.[3] The Treaty of Neuilly after World War I emphasized Jews' equality with other Bulgarian citizens. In 1936, the nationalist and anti-semitic organization Ratnik was established.

In the years preceding World War II, the population growth rate of the Jewish community lagged that of other ethnic groups. In 1920, there were 16,000 Jews, amounting to 0.9% of Bulgarians. By 1934, although the size of the Jewish community had grown to 48,565, with more than half living in Sofia, that only amounted to 0.8% of the general population. Ladino was the dominant language in most communities, but the young often preferred speaking Bulgarian. The Zionist movement was completely dominant among the local population ever since Hovevei Zion.

World War II

Starting in July of 1940, Bulgarian authorities began to institute discriminatory policies against Jews.[7] In December 1940, 352 members of the Bulgarian Jewish community boarded the S.S. Salvador at Varna bound for Palestine. The boat ran aground 100 meters off the coast of Silivri, west of Istanbul, and sank. 223 passengers drowned or died of exposure to frigid waters. Half of the survivors were sent back to Bulgaria while the remainder were allowed to board the Darien II, but were imprisoned at Atlit by the British Mandate authorities.[8]

In March of 1941, the Kingdom of Bulgaria acceded to German demands and entered into a military alliance with the Axis Powers. In the wake of the Wannsee Conference, German diplomats requested, in the spring of 1942, that the Kingdom release into German custody all Jews residing in Bulgarian-controlled territory. The Bulgarian side agreed and began to take steps for the planned deportations of Jews.[7] In the same year, the Bulgarian Parliament and Tsar Boris III enacted the Law for Protection of the Nation, which imposed numerous legal restrictions on Jews in Bulgaria. Specifically, the law prohibited Jews from voting, running for office, working in government positions, serving in the army, marrying or cohabitating with ethnic Bulgarians, using Bulgarian names, or owning rural land. Authorities began confiscating all radios and telephones owned by Jews, and Jews were forced to pay a one-time tax of 20 percent of their net worth.[9][10][11][12] The legislation also established quotas that limited the number of Jews in Bulgarian universities.[12][13] The law was protested not only by Jewish leaders, but also by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church, some professional organizations, and twenty-one writers.[12][14]

In Winter of 1943, the Bulgarian authorities finalized arrangements with the Reich Main Security Office for the first wave of planned deportations, targeting Jews in Sofia (8,000) and the Bulgarian-occupied territories of Thrace, Macedonia and Pirot (~13,000).[7] In February of 1943 the Bulgarian government, possibly in response to the changing tide of the war, indicated through Swiss diplomatic channels its willingness to allow Jews to leave for Palestine on British vessels across the Black Sea. The Bulgarian overture was rebuffed by British Foreign Minister Anthony Eden, on the grounds that "if we do that then the Jews of the world will be wanting us to make a similar offer in Poland and Germany [...] there are simply not enough ships."[15] In the first half of March 1943, Bulgarian military and police carried out the deportation of the majority of non-Bulgarian Jews, 13,341 in total, from the occupied territories and handed them over into German custody. On the eve of the planned deportations, the Bulgarian government made inquiries regarding the destination of the deportees and asked to be reimbursed for the costs of deportation. German representatives indicated that the deportees would be used a labor in agricultural and military projects. As recorded in the German Archives, Nazi Germany paid 7,144.317 leva for the deportation of 3,545 adults and 592 children destined for the Treblinka extermination camp.[16] 4,500 Jews from Greek Thrace and Eastern Macedonia were deported to Poland, and 7,144 from Vardar Macedonia and Pomoravlje were sent to Treblinka. None survived.[17] On March 20, 1943, Bulgarian military police, assisted by German soldiers, took Jews from Komotini and Kavala off the passenger steamship Karageorge, massacred them, and sunk the vessel.[18][19]

No Jews were deported from Bulgaria proper. News of the deportations in the occupied territories incited protest among opposition politicians, members of the clergy and intellectuals in Bulgaria. While Tsar Boris III was initially inclined to continue with the planned deportations, deputy speaker of parliament and prominent member of the ruling party Dimitar Peshev persuaded the him to delay. On March 19, 1943 Peshev introduced a parliamentary resolution to halt the deportations; the resolution was rejected by the ruling party, which forced his resignation by the end of the month. Peshev's resignation was followed by further protests, notably fromMetropolitan Stefan I, which persuaded the Tsar to cancel the deportations entirely in May 1943. Shortly thereafter, the Bulgarian government expelled 20,000 Jews from Sofia to the provinces. The Bulgarian government cited labor shortages as the reason for refusing to transfer Bulgarian Jews into German custody. Expelled men were conscripted as forced labor within Bulgaria. Much of the property left behind was confiscated.[7]

Dimitar Peshev, opposition politicians,the Bulgarian Church, Tsar Boris and ordinary citizens have been variously credited with saving the Bulgarian Jews from deportation.[20][21][7] Later, Bulgaria was officially thanked by the government of Israel for its defiance of Nazi Germany. This story was kept secret by the Soviet Union, because the royal Bulgarian government, the King of Bulgaria and the Church were responsible for the huge public outcry at the time, causing the majority of the country to defend its Jewish population. The communist Soviet regime could not countenance credit to be given to the former authorities, the Church, or the King, as all three were considered enemies of communism. Thus, the documentation proving the saving of Bulgaria's Jews only came to light after the end of the Cold War in 1989. The number of 48,000 Bulgarian Jews was known to Hitler, yet not one was deported or murdered by the Nazis.[20] In 1998, to thank Tsar Boris, Bulgarian Jews in the United States and the Jewish National Fund erected a monument in the Bulgarian Forest in Israel honoring Tsar Boris. However, in July, 2003, a public committee headed by Chief Justice Moshe Bejski decided to remove the memorial because Bulgaria had consented to the delivery of the Jews from occupied territories of Macedonia and Thrace to the Germans.[22]

After World War II and diaspora

After the war, most of the Jewish population left for Israel, leaving only about a thousand Jews living in Bulgaria today (1,162 according to the 2011 census). According to Israeli government statistics, 43,961 people from Bulgaria emigrated to Israel between 1948 and 2006, making Bulgarian Jews the fourth largest group to come from a European country, after the Soviet Union, Romania and Poland.[23] The various migrations outside of Bulgaria has produced descendants of Bulgarian Jews mainly in Israel, but also in the United States, Canada, Australia, and some Western European and Latin American countries.

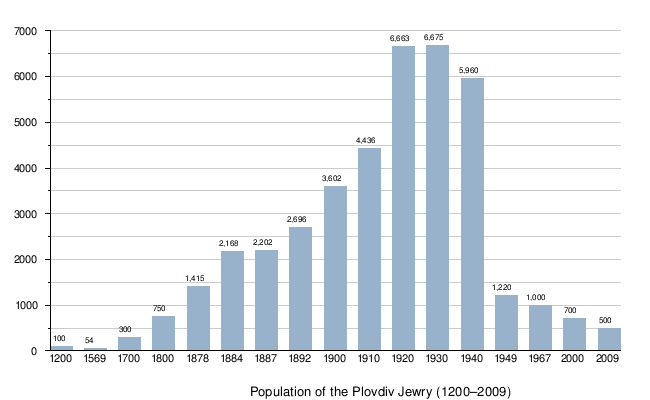

Historical Jewish population

Info from the Bulgarian censuses, with the exception of 2010:[24]

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notable Bulgarian Jews

- Albert Aftalion (1874–1956), economist, from Ruse

- Mira Aroyo (born 1977), musician and member of Ladytron, from Sofia

- Gredi Assa (born 1954 in Pleven), professor, Academy of Fine Arts, Sofia

- Maksim Behar (born 1955), businessman and public relations professional, from Shumen

- Elias Canetti (1905–1994), Nobel Prize-winning writer, from Ruse

- Tobiah ben Eliezer (11th century), talmudist and poet, from Kostur

- Itzhak Fintzi (born 1933), actor, from Sofia

- Samuel Finzi (born 1966), actor, from Plovdiv

- Solomon Goldstein (1884–1968/1969), communist politician, from Shumen

- Moshe Gueron (born 1926), cardiologist and researcher, from Sofia

- Joseph Karo (1488–1575), author of Shulchan Aruch, raised in Nikopol

- Nikolay Kaufman (born 1925), musicologist and composer, from Ruse

- Milcho Leviev (born 1937), composer and musician, from Plovdiv

- Jacob L. Moreno (1889–1974), founder of psychodrama, father from Pleven

- Judah Leon ben Moses Mosconi (1328–?), talmudist born at Ohrid

- Eliezer Papo (1785–1828) writer on religious subjects, born in Sarajevo, became rabbi in Silistra

- Jules Pascin (1885–1930), modernist painter, from Vidin

- Isaac Passy (1928–2010), philosopher, from Plovdiv

- Solomon Passy (born 1956), politician and former Minister of Foreign Affairs, from Plovdiv

- Valeri Petrov (1920–2014), writer, from Sofia

- Solomon Rozanis (1919–2004), supreme court judge and lawyer, from Ruse

- Sarah-Theodora (14th century), wife of Tsar Ivan Alexander

- Pancho Vladigerov (1899-1978) composer, teacher. Mother was Jewish. Bulgaria's National Academy of Music in Sofia is named for him.

- Angel Wagenstein (born 1922), film director, from Plovdiv

- Alexis Weissenberg (1929–2012), pianist, from Plovdiv

- Israel Calmi (1885 – 1966), member of the Jewish Consistory of Bulgaria

Knesset members

- Binyamin Arditi (1897–1981), from Sofia

- Michael Bar-Zohar (born 1938), from Sofia

- Shimon Bejarno (1910–1971), from Plovdiv

- Ya'akov Nehoshtan (born 1925), from Kazanlak

- Ya'akov Nitzani (1900–1962), from Plovdiv

- Victor Shem-Tov (1915–2014), from Samokov

- Emanuel Zisman (1935–2009), from Plovdiv

See also

References

- ↑ "2001 census data". nsi.bg (in Bulgarian). Nastional Statistical Institue of Bulgaria. March 1, 2001. Archived from the original on May 27, 2012. Retrieved October 25, 2016. "Ethnic Minorities in Bulgaria". nccedi.government.bg (in Bulgarian). National Council for Cooperation on Ethnic and Integration Issues. 2006. Archived from the original (pdf) on April 16, 2009. Retrieved October 25, 2016.

- ↑ "History". shalompr.org (in Bulgarian). Организация на евреите в България "Шалом" (Organization of Jews in Bulgaria "Shalom"). 2015. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Stefanov, Pavel (2002). "Bulgarians and Jews throughout History". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. Newberg, Oregon: George Fox University. 22 (6): 1–11. ISSN 1069-4781. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ↑ Kesiakova, E. (1989). "Antichna sinagoga vuv Philipopol". Arheologia. 1: 20–33.

- ↑ Kochev, N. (1978). "Kum vuprosa za nadpisa ot Oescus za t. nar. arhisinagogus". Vekove. 2: 71–74.

- ↑ Kraabel, A. T. (1982). "The Excavated Synagogues of Late Antiquity from Asia Minor to Italy". 16th Internationaler Byzantinistenkongress (in German). Vienna. 2 (2): 227–236.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Bulgaria". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 2016-11-09.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Jews fleeing the Nazis drown in Sea of Marmara". haaretz.com. Haaretz.

- ↑ Marushiakova, Elena; Vesselin Popov (2006). "Bulgarian Romanies: The Second World War". The Gypsies during the Second World War. Univ of Hertfordshire Press. ISBN 0-900458-85-2.

- ↑ Fischel, Jack (1998). The Holocaust. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 69. ISBN 0-313-29879-3.

- ↑ Wyman, David S.; Charles H. Rosenzveig (1996). The world reacts to the Holocaust. JHU Press. p. 265. ISBN 0-8018-4969-1.

- 1 2 3 Benbassa, Esther; Aron Rodrigue (2000). Sephardi Jewry: a history of the Judeo-Spanish community, 14th-20th centuries. University of California Press. p. 174. ISBN 0-520-21822-1.

- ↑ Levin, Itamar; Natasha Dornberg; Judith Yalon-Fortus (2001). His majesty's enemies: Great Britain's war against Holocaust victims and survivors. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-275-96816-2.

- ↑ Levy, Richard S (2005). Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution. ABC-CLIO. p. 90. ISBN 1-85109-439-3.

- ↑ A History of Israel: From the Rise of Zionism to Our Time by Howard M. Sachar, Alfred A. Knopf, N.Y., 2007, p. 238.

- ↑ Macedonia-online

- ↑ (eds.), Bruno De Wever ... (2006). Local government in occupied Europe: (1939–1945). Gent: Academia Press. p. 206. ISBN 978-90-382-0892-3.

- ↑ Facing Our Past Helsinki Group, Bulgaria

- ↑ "The Virtual Jewish History Tour Bulgaria". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved 2006-11-26. "Encyclopedia Judaica: Cuomotini, Greece". Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved October 1, 2015.

- 1 2 Bar-Zohar, Michael (2001-07-04). Beyond Hitler's Grasp: The Heroic Rescue of Bulgaria's Jews. Adams Media Corporation. ISBN 9781580625418. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- ↑ Todorov, Tzvetan (2003). The Fragility of Goodness: Why Bulgaria's Jews Survived the Holocaust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-11564-1.

- ↑ Alfassa, Shelomo (August 17, 2011). Shameful Behavior: Bulgaria and the Holocaust. Judaic Studies Academic Paper Series. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-257-95257-1. ISSN 2156-0390.

- ↑ "Immigrants by period of immigration, country of birth and last country of residence" (in Hebrew and English). The Central Bureau of Statistics (Israel). Retrieved 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Berman Institute. "World Jewish Population, 2010" (PDF). University of Connecticut. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

Further reading

- Ben-Yakov, Avraham (1990). Encyclopaedia of the Holocaust. 1. New York: Macmillan. pp. 263–272. ISBN 0-02-896090-4. (map, illus.)

- Stefanov, Pavel (2002). "Bulgarians and Jews throughout History". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. Newberg, Oregon: George Fox University. 22 (6): 1–11. ISSN 1069-4781. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Stefanov, Pavel (2006). "The Bulgarian Orthodox Church and the Holocaust: Addressing Common Misconceptions". Occasional Papers on Religion in Eastern Europe. Newberg, Oregon: George Fox University. 26 (2): 10–19. ISSN 1069-4781. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Trankova, Dimana; Georgieff, Anthony. A Guide to Jewish Bulgaria. Sofia: Vagabond Media. p. 168. ISBN 978-954-92306-3-5.

- Comforty, Jacky (2001). "The Optimists: A film about the Rescue of the Bulgarian Jews during the Holocaust". See also the resources page on the same website.

- Chary, Frederick B. (1972). The Bulgarian Jews and the Final Solution, 1940-1944. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 45.

- L. Ivanov. Essential History of Bulgaria in Seven Pages. Sofia, 2007.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jewish community of Bulgaria. |

- "Records of the Open Media Research Institute (OMRI): Bulgarian Subject Files - Social Issues: Minorities: Jews". osaarchivum.org. Budapest: Open Society Archives, Central European University. Jun 26, 2008. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- Empty Boxcars (2011) Documentary on IMDb and Video on YouTube

- Alfassa, Shelomo. "Clarifying 70 Years of Whitewashing and Inaccuracies: The Bulgarian Government and its Interaction with Jews During the Holocaust".

- "Saving the Jews of Bulgaria" (in Bulgarian). Bulgarian State Archives Agency. Retrieved October 4, 2015.