Capture of Oppy Wood

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Capture of Oppy Wood was an engagement on the Western Front of the First World War on 28 June 1917.[1] The Arras Offensive of 1917 ended with the Germans in possession of a fortified wood to the west of the commune of Oppy, which overlooked British positions. The wood was 1-acre (0.40 ha) in area and contained many German observation posts, machine-guns and trench-mortars. New German defensive tactics adopted after the Battle of the Somme, of defence in depth and rapid counter-attack, had been enforced on the German 6th Army after the disaster of 9 April. A British attack was defeated everywhere on 3 May, except at Fresnoy which was captured by the 1st Canadian Division. The attack on Oppy Wood by 92nd Brigade of the 31st Division during the Third Battle of the Scarpe (3–4 May), was repulsed with many British casualties. The area was defended by the 1st Guard Reserve Division and the 15th Reserve Division, which had not needed to call on specialist Eingreif (counter-attack) divisions.

A second attack took place on 28 June, as part of a series of feints, intended to simulate a threat to the cities of Lens in the First Army area and Lille in the Second Army area. The attack was conducted by the 15th Brigade of the 5th Division and the 94th Brigade of the 31st Division, which advanced on a front extending from Gavrelle in the south to the north of Oppy Wood. After a hurricane bombardment, the objectives were captured with few British losses and German counter-attacks were defeated by artillery-fire. An attack at the same time, by the 4th Canadian Division and the 46th Division astride the Souchez river also succeeded. Operations to continue the encirclement of Lens, with an attack by the Canadian Corps on Hill 70 to the north, were postponed until August, due to a shortage of artillery. The feint attacks failed to divert German preparations to defend Flanders, which included the transfer of ten divisions to the 4th Army, despite claims by the 6th Army command that an offensive towards Lens was being prepared. The operations did succeed in diverting German attention from the French front.

Background

Strategic developments

Before the Third Battle of the Scarpe, the cancellation of the French part in the Nivelle Offensive seemed certain. A continuation of British attacks towards Cambrai would be made pointless, in the absence of French operations to the south and Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig decided to continue operations on the Arras front to reach a good defensive line, then to conduct surprise attacks, to keep German troops in the area. Preparations were made to begin operations in Flanders, with the first offensive at Messines to begin in early June.[2] Despite uncertainty about the French attack on the Aisne, which was due on 4–5 May, a plan for an attack by the British Fifth, Third and First armies on a 14-mile (23 km) front, was not cancelled and the First Army objectives were given as Oppy and Fresnoy.[3]

The move of the bulk of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to Flanders in late May and June, left the First Army with twelve divisions to hold a 34-mile (55 km) front from Arras to Armentières on the Lys river. During the period needed to prepare the offensive at Ypres after the Battle of Messines (7–14 June), threats to Lens and Lille were planned for the end of June. The First Army was to operate on a three-corps front, in which the XIII Corps was to advance 200–500 yards (180–460 m) between Gavrelle and Oppy, on a 2,300-yard (2,100 m) front, while to the north the Canadian Corps was to attack on both banks of the Souchez river towards Avion.[4]

Tactical developments

Experience of the 1st Army in the Somme Battles, (Erfahrungen der I Armee in der Sommeschlacht) was published on 30 January 1917. During the Battle of the Somme in 1916, Colonel Fritz von Lossberg (Chief of Staff of the 1st Army) had been able to establish a line of "relief" divisions (Ablösungsdivisionen), with the reinforcements from Verdun which had begun to arrive in September. In his analysis of the battle, Lossberg opposed the granting of discretion to front trench garrisons to retire, as he believed that manoeuvre did not allow the garrisons to evade Allied artillery fire, which could blanket the forward area, make evasion futile and invite enemy infantry to occupy vacated areas unopposed. Lossberg considered that spontaneous withdrawals would disrupt the counter-attack reserves as they deployed and further deprive battalion and division commanders of the ability to conduct an organised defence, which the dispersal of infantry over a wider area had already made difficult. Lossberg and others had severe doubts as to the ability of relief divisions to arrive on the battlefield in time to conduct an immediate counter-attack (Gegenstoss) from behind the battle zone. Lossberg wanted the Somme practice of fighting in the front line to be retained and authority devolved no further than the battalion, so as to maintain organizational coherence in anticipation of a methodical counter-attack (Gegenangriff) by the relief divisions after 24–48 hours. Ludendorff was sufficiently impressed by the Lossberg memorandum, to add it to the new Manual of Infantry Training for War.[5]

The British training manual SS 143 of February 1917, marked the end of attacks made by lines of infantry with a few detached specialists.[6] The platoon was divided into a small headquarters and four sections, one with two trained grenade-throwers and assistants, the second with a Lewis gunner and nine assistants carrying 30 drums of ammunition, the third section comprising a sniper, scout and nine riflemen and a fourth section of nine men with four rifle-grenade launchers.[7] The rifle and hand-grenade sections, were to advance in front of the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections, in two waves or in artillery formation, which covered an area 100 yards (91 m) wide and 50 yards (46 m) deep, with the four sections in a diamond pattern, the rifle section ahead, rifle grenade and bombing sections to the sides and the Lewis gun section behind, until resistance was met. German defenders were to be suppressed by fire from the Lewis-gun and rifle-grenade sections, while the riflemen and hand-grenade sections moved forward, preferably by infiltrating round the flanks of the resistance, to overwhelm the defenders from the rear.[8]

Changes in equipment, organisation and formation were elaborated in SS 144 The Normal Formation For the Attack of February 1917, which recommended that the leading troops should push on to the final objective, when only one or two had been set. For a greater number of objectives, when artillery covering fire was available for the depth of the intended advance, fresh platoons should "leap-frog" through the leading platoons to the next objective.[9] The new organisation and equipment gave the infantry platoon the capacity for fire and manoeuvre, even in the absence of adequate artillery support against German defences. To bring uniformity in adoption of the methods laid down in the revised manuals and others produced over the winter, Haig established a BEF Training Directorate in January 1917 to issue manuals and oversee training. SS 143 and its companion manuals like SS 144, provided British infantry with off-the-peg tactics, devised from the experience of the Somme and from French Army operations, to go with the new equipment made available by increasing British and Allied war production and better understanding of the organisation necessary to exploit it in battle.[10] For the attack on 3 May, the Fifth Army wanted to make a night assault, to evade German machine-gun fire but the Third and First armies needed to attack in daylight and Haig enforced a compromise zero hour of 3:45 a.m. The moon was close to full and set only sixteen minutes before zero hour; on many parts of the attack front, troops assembling were silhouetted as the moon sank behind them.[11] In the XIII Corps the 2nd Division had already had many casualties and was exhausted, so the fresh 31st Division took over the right flank of the 2nd Division front.[12]

Prelude

British plans of attack

The First Army plan had been based on an assumption of a dawn attack and no preparations had been made for an advance at night, such as putting out boards with luminous paint on the German wire, taking compass-bearings or organising intermediate objectives. Sunrise was not until 5:22 a.m. and it would not be possible to distinguish objects at 50 yards (46 m) until 4:05 a.m.[11] An attack on German observation balloons was planned in the First Army area, to be carried out by Nieuport Scout aircraft of the Tenth Wing of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC), which was to be covered by an artillery barrage and bombing raids further behind the German lines were arranged. The attack of the XIII Corps was to be conducted by two divisions on a front from the south end of Gavrelle, to the wood south of Fresnoy. The depleted and exhausted state of the 2nd Division, led to its attack front being reduced to 1,100 yards (1,000 m), from Greenland Hill to Oppy Support Trench and Fresnoy, by the extension of the 31st Division front to a width of 3,500 yards (3,200 m). The Germans had managed to retain 750 yards (690 m) of the Oppy Line, to the west of Oppy Wood in the Battle of Arleux (28–29 April), which complicated the task of the 31st Division. Oppy Wood was full of fallen trees and tangled branches and a long slope to the west left the British field artillery at extreme range, which reduced accuracy. The division was supported by nine field artillery brigades and extra machine-guns from the 63rd Division and the 1/1st Northumberland Hussars, the XIII Corps cavalry regiment.[13]

The First Army planned to attack in the first half of July, as part of an attempt by the First and Second armies to keep German troops away from the Flanders front for as long as possible, with feint attacks on Lens and Lille. The dispatch of heavy and siege artillery to Flanders, led the First Army commander General Horne, to bring forward the attack to 28 June and to limit the attack to the XIII Corps operation against Oppy and Gavrelle. Artillery moving north to Flanders from the Third Army, was diverted temporarily to increase the weight of the First Army bombardment, which was to take place on a 14-mile (23 km) front, to create the impression of an imminent threat against Lens.[4] XIII Corps had four divisions, with the 31st and 63rd divisions alternating in the line on the right and the 2nd Division and 5th Division alternating on the left flank. The 5th Division withdrew the 15th Brigade for a week of training for the attack, which was conducted by all four battalions. The plan required the artillery to cut the German wire but leave the German trenches intact, so that the British infantry could occupy them.[14]

British offensive preparations

A corps conference was held on 30 April, at which the state of the 2nd Division was discussed but it was still required to participate in the attack. A composite brigade was formed from the survivors of the three brigades.[15][lower-alpha 1] Three field artillery brigades, corps and army heavy artillery were arranged in support of the composite brigade and the 1st Canadian Brigade was to attack on the northern flank.[16] The 63rd Division took over the line from the 31st Division and the right flank sector of the 5th Division on 4–5 July. The division sapped forward down the long slope, from the old German Fampoux–Farbus Switch Line, which had become the British "army" line of resistance, by establishing sap heads and posts which were linked overnight.[17] Before the attack, Fresnoy was subjected to an incendiary bombardment by Livens Projectors to create a diversion.[18][lower-alpha 2] A raid by the 92nd Brigade was planned for 22 June, to inflict casualties on the Germans, study the German defences and note the position of machine-gun nests.[19]

Zero hour was set at 10:20 p.m., when the adjacent troops of the 93rd Brigade were to open rapid fire with small-arms and to fire German rockets to distract the defenders. On the 92nd Brigade front, the artillery was not to fire until zero hour, at which it would begin 50 yards (46 m) from Cadorna Trench for one minute and then lift onto the trench. Three minutes later, the barrage was to move forward for 300 yards (270 m), lift one minute later to Windmill Trench for forty minutes and then slowly diminish. The divisions on the flanks were also to fire diversionary barrages.[19] Little German return fire from Oppy Wood was encountered but small parties of German troops were found in front of Cadorna Trench. The trench was discovered to have been destroyed by the bombardment and the raiders passed beyond it without realising. German survivors retreated towards Windmill Trench, were caught by the British barrage and several prisoners were taken. The raiders began to withdraw from Windmill Trench and stopped a German attempt to counter-attack around the northern flank, which was ambushed by a Lewis gun squad. The British lost 44 casualties.[20]

German defensive preparations

German Corps headquarters had been detached from their component divisions and given permanent areas to hold under a geographical title on 3 April 1917. The VIII Reserve Corps holding the area north of Givenchy became Gruppe Souchez, I Bavarian Reserve Corps became Group Vimy and held the front from Givenchy to the Scarpe river with three divisions, Group Arras (IX Reserve Corps) was responsible for the line from the Scarpe to Croisilles and Group Quéant (XIV Reserve Corps) from Croisilles to Mœvres. Henceforth, divisions would move into the area and come under the authority of the corps (Gruppe) for the duration of their term, then be replaced by fresh divisions.[21] On the Gruppe Vimy front, the 1st Guard Reserve Division, the last of the Eingreif divisions still in the line, had swapped a tired regiment for a fresh one from the 185th Division and held the line from south of Gavrelle to the Oppy–Bailleul road. The fresh 15th Reserve Division, held the line further north from the road to beyond Fresnoy.[22]

Battle

3 May

Operations on the First Army front began with attacks on German observation balloons, in which four were shot down and another four were damaged. XIII Corps attacked on a 4,600-yard (4,200 m) front, from the south of Gavrelle to the vicinity of Fresnoy, with the 2nd Division, which had been reduced by casualties to a remnant and the fresh 31st Division. The German defenders saw the British infantry forming up in the moonlight, in an assembly trench 250 yards (230 m) from the objective. At midnight a German patrol was seen and at 12:30 a.m. a German bombardment began for twenty minutes and then a second bombardment began from 1:30 a.m. until zero hour. There were few British casualties but the shelling caused considerable confusion and the German bombardment increased, when the British preliminary bombardment began. The British troops advanced in four waves, which were illuminated by German rockets and very lights and engaged by massed small-arms fire; the three battalions of the 93rd Brigade were still able to advance and some units reached the final objective.[23]

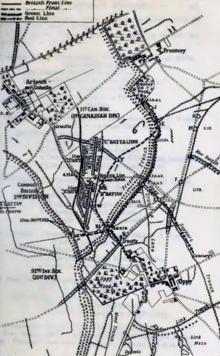

On the left, the three attacking battalions of the 92nd Brigade were subjected to a "tremendous" barrage on their assembly-positions, just before zero hour which caused much disorganisation. The darkness in this area was increased by Oppy Wood and the infantry could not see the barrage lift. The right-hand battalion was unable to advance and troops in the centre and left flank battalions found areas of uncut wire and lost many casualties, when they bunched up at the gaps before reaching the wood, which they found to be full of fallen trees covered in barbed wire. The British troops were then cut off and captured or forced back with many casualties. Many of the troops were stranded in no man's land and had to wait all day under fire from snipers, machine-guns and artillery until nightfall, before completing the retirement.[24] A German counter-attack pushed the 92nd Brigade back and retook Gavrelle Windmill for a short time, until forced back by another British attack.[13] It was discovered after the war that the majority of the Hull Commercials who had been taken prisoner during the attack, had advanced as far as Oppy village.[23]

The 2nd Division attacked with a composite brigade only c. 1,800 strong, despite being made up of the least depleted battalions of the division. The first objective was a German trench behind the Arleux Loop, from a wood south of Fresnoy and further to the right; a second objective was set at the Fresnoy–Oppy road.[25] The composite brigade was bombarded as it moved forward to the assembly-positions, which caused many losses and delays in crowded communication trenches, some of the troops failed to reach the jumping-off positions in time. "B" Battalion managed to advance on the left but was then driven back, by a German counter-attack from Oppy; "C" Battalion advanced in contact with Canadian troops on the flank, reached the first objective on the right and the final objective on the left, before the German counter-attack from Oppy, which in this area was repulsed by small-arms fire. On the "B" Battalion front, German troops bombed their way northwards and threatened the divisional junction with the 1st Canadian Division, which had captured Fresnoy. Reserves and some Canadian troops managed to form a block, 400 yards (370 m) south of the left flank of the 2nd Division and touch was regained with the 1st Canadian Division south-east of Fresnoy.[26]

28 June

The day was dull and humid and at 5:30 p.m., German artillery bombarded the British jumping-off trenches for ten minutes and caused c. 200 casualties in the two attacking brigades. At 7:00 p.m., a British hurricane bombardment began from Gavrelle to Hulluch, along the 14-mile (23 km) front of the XIII Corps and I Corps, as part of a feint against Lens. Howitzers fired smoke-shell to create a screen, to the north of the 5th Division attack and then a thunderstorm began, the infantry advancing at 7:10 a.m. amidst lightning and torrential rain. In the XIII Corps area, the 94th Brigade of the 31st Division advanced north of Gavrelle and the 15th Brigade of the 5th Division attacked Oppy on a 2,300-yard (2,100 m) front. Despite the German bombardment on the jumping-off trenches, the British troops advanced swiftly across no man's land behind a creeping barrage, before the German counter-barrage fell three minutes later. On the 5th Division front, the German trenches were strongly held but the British arrived so quickly that few were able to resist, except on the left flank where the objective was further away. The 15th Brigade took 143 prisoners, several machine-guns and trench mortars and the 94th Brigade took a similar amount; 280 German dead were counted on the battlefield. Gavrelle Mill and the other objectives were captured easily but the rain interfered with consolidation, which had begun by 9:00 p.m. The new positions gave a good view to the north and east towards Neuvireuil and Fresnes and to the south-east around Greenland Hill.[27] After the attack, German artillery-fire was concentrated on Fresnoy, which had been subjected to an incendiary bombardment.[18]

German 6th Army counter-attacks

The German front-holding divisions defeated the British attacks all along the front on 3 May and Eingreif divisions were not called upon. Counter-attacks by companies were often all that was needed to repulse British troops, where they had gained footholds in the German defences. Fresnoy was captured by the Canadian Corps and hasty German counter-attacks there were repulsed, the 15th Reserve Division reporting 650 casualties around the village; losses inside Fresnoy were not recorded but were believed to be higher.[28] The 5th Bavarian Division was ordered to prepare an organised counter-attack (Gegenangriff), to recapture Fresnoy and attacked on 8 May, with all three regiments and the support of 27 field and 17 heavy artillery batteries, plus those of the neighbouring divisions. The right flank brigade was delayed for a short time at Fresnoy Park, then found only a battlefield strewn with dead soldiers and abandoned equipment. The brigade in the centre lost the barrage as it floundered in mud and managed to advance only after the northern brigade reached its objective. The southern brigade managed to push forward and then bomb northwards to roll up the British front but despite rapid success, the division lost 1,585 casualties.[29]

Air operations

Losses of British corps aircraft declined after April, which had been the worst in the war and air fighting returned to the German rear areas.[lower-alpha 3] An attack on German observation balloons was planned, during the lull in infantry operations before May and the pilots practised flying at low altitude, to exploit the cover of trees, dips in the ground and houses. Observation balloons could be winched down quickly, which made them difficult to shoot down; the commander of the Tenth Wing RFC, Lieutenant-Colonel W. Freeman, arranged for an artillery barrage on the German trenches as a diversion, to cover aircraft from 40 Squadron, which made a surprise attack. At 9:00 a.m. on 2 May, the artillery barrage began and six Nieuport pilots attacked the balloons, which were found to be still airborne, at heights up to 2,000 feet (610 m). Four balloons were shot down in flames, four were damaged and all of the Nieuports returned damaged by small arms fire.[31]

On 3 May, British aircraft were detailed for special counter-attack reconnaissance, after the experience of the new German tactics of lightly holding the front line and counter-attacking with reserves and Eingreif divisions. The British aircraft flew low over the battlefield behind captured positions, from dawn to nightfall looking for signs of German counter-attacks, to report them immediately to the British artillery. Bombardments from both sides and infantry attacks and counter-attacks, made the battlefield so chaotic, that airborne observers were not able to see clearly, except for observers of 43 Squadron, who saw German troops massing opposite the XIII Corps front. Five Sopwith 1½ Strutters were sent from the squadron, to attack the German infantry and machine-gunned them from 50–300 feet (15–91 m); low-altitude attacks on other bodies of troops were carried out in the afternoon.[32] Tactical bombing took place, with attacks on the stations at Don, Busigny Junction, Brebières and the aerodrome at Eswars. After dark bombing continued on trains and three were hit by low-level attacks of the night-bombing specialists of 100 Squadron, along with railway junctions and Tourmignies airfield.[33]

Aftermath

Analysis

The British divisions had begun the Arras offensive well-trained and equipped but casualties had been replaced by poorly trained drafts and the British divisions moving north to Flanders, had received the pick of the replacements. In the Canadian divisions, replacements tended to be older, of better build and had received a longer period of training. The Canadian divisions were able to maintain their fighting-power, despite participating in a number of attacks at short intervals. The German defences between Oppy and Méricourt had proved to be difficult to capture, because the Germans had elaborately fortified the area to protect Fresnoy, which commanded much of the ground on either flank.[34] The 31st Division headquarters, had expected that the attack of 3 May, would encounter demoralised troops and that the creeping barrage would neutralise all resistance. On part of the front, the British found that rather than being shaken, the Germans were massing for an attack and that some of the German wire at the south-western corner of the wood was uncut. One company fought their way into the village but the rest were held up despite attacking three times.[35]

The attack on 28 June, captured the German first line from Gavrelle to Oppy Wood and advanced the British line about 0.5-mile (0.80 km). The Germans were pushed back to an inferior second position trench and the village of Oppy. With the British in possession of the high ground north of Gavrelle, which had been captured by the 63rd Division at the Battle of Arleux on 28 April, a German counter-attack from Oppy village was impossible and the area was consolidated by 4–5 July.[17] The attack by the Canadian Corps and I Corps to the north was also successful, the 3rd Canadian Division forming a defensive flank on the Arleux–Avion road and linking with the 4th Canadian Division in Avion. Most of Avion, Eleu dit Leauvette and the German defences on the east side of Hill 65, were captured by the 4th Canadian and 46th divisions.[27]

Casualties

On 3 May, the 31st Division lost 1,900 casualties in the attack on Oppy Wood.[36] The 2nd Division composite brigade had 517 losses, which left the division "bled white" with a "trench strength" of only 3,778 men.[37] On 8 May, the 5th Bavarian Division lost 1,585 casualties in the counter-attack at Fresnoy.[29] In the attack of 28 June the 31st Division lost c. 100 men and the 5th Division casualties were 352 men.[38][39]

Subsequent operations

By 5 May, the 5th Division had relieved the 2nd Division and the 1st Canadian Division, XIII Corps taking over the front from north of Oppy to beyond Fresnoy. The village was in a sharp salient created by the attack of 3 May, with the Oppy–Méricourt line still in German possession between Fresnoy and Oppy. On 7 May, the RFC attacked German observation balloons again and shot down seven for the loss of one aircraft. On 8 May, a German attack recaptured Fresnoy and annihilated a British battalion as it tried to withdraw from the village. British and Canadian troops in the vicinity were pushed back to the eastern fringe of Arleux and the 5th Division withdrew its left flank to the Arleux–Neuvireuil road. A counter-attack on 9 May, reached Fresnoy but was later forced back, midway between Arleux and Fresnoy. No fresh divisions remained in the First Army and artillery had begun to be moved northwards to the Second Army on 14 May. On 18 May, a small operation by a battalion of the 31st Division was mounted at Gavrelle, which failed to reach the German front-line trench.[40]

On the night of 14/15 July, the 63rd Division dug a new front line, from Oppy Wood to beyond Gavrelle Windmill and on 20 July, a raid on Gavrelle Trench met feeble resistance and found that the German trenches were in poor condition. The British pushed their lines as close as possible to the German front line, to evade German artillery-fire and two artillery batteries were brought forward 2,000 yards (1,800 m), to increase the effect of several hurricane artillery and machine-gun bombardments, which were intended to keep the Germans in anticipation of another attack. The British positions around the windmill were bombarded by German artillery, whenever a British operation took place but the infantry positions proved immune to bombardment, which fell on the artillery instead, which frequently changed position and eventually had to be withdrawn.[41]

See also

Victoria Cross

- 2nd Lieutenant J. Harrison, 11th E.Yorks.[36]

Commemoration

The units which attacked Oppy Wood were awarded the battle honour Oppy.[42] A wood on the outskirts of Hull, Yorkshire, is named Oppy Wood in memory of the men of the East Yorkshire Regiment who were killed in the attack of 3 May.[43]

Notes

- ↑ On 1 May, the fighting strengths of the 2nd Division brigades were: 5th Infantry Brigade, 1,237 men, 6th Infantry Brigade, 1,322 men, 99th Infantry Brigade, 1,028 men.[15]

- ↑ "Special Companies" RE filled cylinders with oil and discharged them electrically in salvoes from Livens Projectors. On impact with the ground, they exploded and produced a terrifying effect. Machine-gun and shrapnel-fire were added and sometimes gas was substituted for oil.[18]

- ↑ From 30 January 1916, each British army had a Royal Flying Corps brigade attached, which was divided into wings: the "corps wing" contained squadrons responsible for close reconnaissance, photography and artillery observation on the front of each army corps and an "army wing" which by 1917, conducted long-range reconnaissance and bombing, using the aircraft types with the highest performance.[30]

Footnotes

- ↑ James 1924, p. 19.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 427.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 431.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, pp. 112–113.

- ↑ Wynne 1939, p. 161.

- ↑ Bellis 1916, pp. 83–107.

- ↑ Griffith 1996, p. 77.

- ↑ Corkerry 2001, p. 88.

- ↑ Bond 1999, p. 86.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, pp. 209–211.

- 1 2 Falls 1940, p. 432.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 446.

- 1 2 Falls 1940, pp. 445–446.

- ↑ Hussey & Inman 1921, pp. 160, 164.

- 1 2 Wyrall 1921, p. 439.

- ↑ Wyrall 1921, p. 440.

- 1 2 Jerrold 1923, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 Hussey & Inman 1921, p. 166.

- 1 2 Bilton 2005, p. 131.

- ↑ Bilton 2005, p. 132.

- ↑ Sheldon 2008, p. 40.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 453.

- 1 2 Bilton 2005, p. 94.

- ↑ Bilton 2005, pp. 86–87.

- ↑ Bilton 2005, p. 115.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 447–448.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1948, p. 114.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 453–454.

- 1 2 Falls 1940, p. 523.

- ↑ Jones 1928, pp. 147–148.

- ↑ Jones 1931, p. 371.

- ↑ Jones 1931, p. 373.

- ↑ Jones 1931, p. 374.

- ↑ Falls 1940, p. 451.

- ↑ Bilton 2005, p. 95.

- 1 2 Falls 1940, p. 447.

- ↑ Wyrall 1921, p. 444.

- ↑ Edmonds 1948, pp. 113–114.

- ↑ Hussey & Inman 1921, p. 165.

- ↑ Falls 1940, pp. 520–522.

- ↑ Jerrold 1923, pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Rodger 2003, p. 129.

- ↑ TWT 2013.

References

- Bellis, M. (1996) [1916]. Instructions for the Training of Divisions for Offensive Action (repr. ed.). London: Military Press International. ISBN 978-0-85420-195-2.

- Bilton, D. (2005). Oppy Wood. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-248-3.

- Bond, B. (1999). Look To Your Front: Studies in the First World War. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 978-1-86227-065-7.

- Corkerry, S., ed. (2001) [1916]. Instructions for the Training of Divisions for Offensive Action (repr. ed.). Milton Keynes: Military Press. ISBN 978-0-85420-250-8.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1991) [1948]. Military Operations France and Belgium 1917: 7 June – 10 November. Messines and Third Ypres (Passchendaele). History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-166-4.

- Falls, C. (1992) [1940]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1917: The German Retreat to the Hindenburg Line and the Battles of Arras. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum & Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-180-0.

- Griffith, P. (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack 1916–1918. London: Yale. ISBN 978-0-300-06663-0.

- Hussey, A. H.; Inman, D. S. (2002) [1921]. The Fifth Division in the Great War (PDF) (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Nisbet. ISBN 978-1-84342-267-9. Retrieved 8 September 2013.

- James, E. A. (1990) [1924]. A Record of the Battles and Engagements of the British Armies in France and Flanders 1914–1918 (London Stamp Exchange ed.). Aldershot: Gale & Polden. ISBN 978-0-948130-18-2.

- Jerrold, D. (2009) [1923]. The Royal Naval Division (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-1-84342-261-7.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF). II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-413-0. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- Jones, H. A. (2009) [1931]. The War in the Air, Being the Part played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF). III (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-1-84342-414-7. Retrieved 5 October 2014.

- "Oppy Wood". News. The Woodland Trust. 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Rodger, A. (2003). Battle Honours of the British Empire and Commonwealth Land Forces. Marlborough: Crowood Press. ISBN 978-1-86126-637-8.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2008). The German Army on Vimy Ridge 1914–1917. Barnsley: Pen & Sword. ISBN 978-1-84415-680-1.

- Wynne, G. C. (1976) [1939]. If Germany Attacks: The Battle in Depth in the West (Greenwood Press, NY ed.). London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-8371-5029-1.

- Wyrall, E. (2002) [1921]. The History of the Second Division, 1914–1918. II (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Thomas Nelson and Sons. ISBN 978-1-84342-207-5. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

Further reading

- Corkerry, S., ed. (2001) [1917]. Instructions for the Training of Platoons for Offensive Action (repr. ed.). Milton Keynes: Military Press. ISBN 978-0-85420-250-8.

- Nicholson, G. W. L. (1962). Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914–1919 (PDF). Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War. Ottawa: Queen's Printer and Controller of Stationery. OCLC 59609928. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Capture of Oppy Wood. |

- The Accrington Pals: Oppy-Gavrelle, May–June 1917

- War diary, 22nd (Service) Battalion Royal Fusiliers Operations in the Battle of Arras and near Oppy Wood