Africa (Roman province)

| Provincia Africa Proconsularis | |||||

| Province of the Roman Empire | |||||

| |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Zama Regia, then Carthago | ||||

| Historical era | Antiquity | ||||

| • | Established after the Third Punic War | 146 BC | |||

| • | Invasion of the Vandals | 5th century | |||

| Today part of | | ||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Tunisia | ||||||||||||

| Prehistoric | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Early Islamic | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Medieval | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Early modern | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Modern | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

Modern times |

|

|

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Libya | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

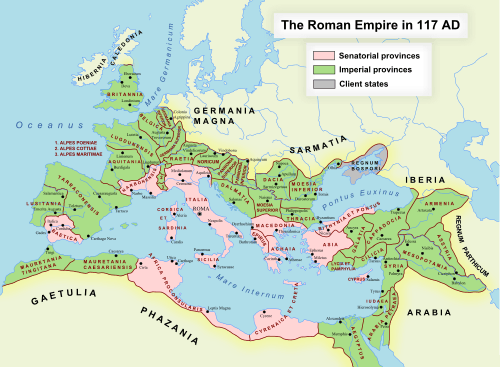

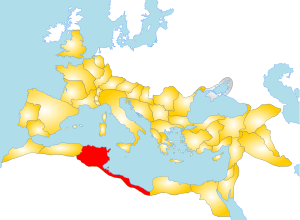

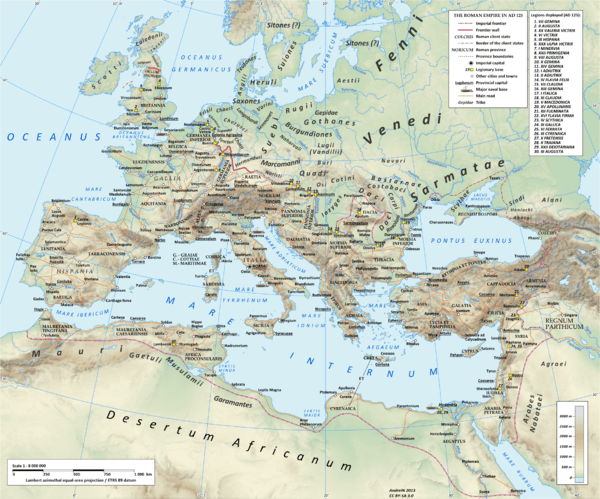

The Roman province of Africa Proconsularis was established after the Romans defeated Carthage in the Third Punic War. It roughly comprised the territory of present-day Tunisia, the northeast of modern-day Algeria, and the small Mediterranean Sea coast of modern-day western Libya along the Syrtis Minor.

It was one of the wealthiest provinces in the western part of the empire, second only to Italia. The Arabs later named roughly the same region as the original province Ifriqiya, a rendering of Africa, from the Latin language.

History

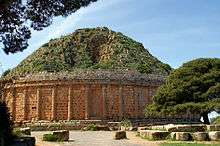

The acquired for the province of Africa was the site of the ancient city of Carthage. Other large cities in the region included Hadrumetum (modern Sousse, Tunisia), capital of Byzacena, Hippo Regius (modern Annaba, Algeria). The province was established by the Roman Republic in 146 BC, following the Third Punic War.

Rome established its first African colony, Africa Proconsularis or Africa Vetus (Old Africa), governed by a proconsul, in the most fertile part of what was formerly Carthaginian territory. Utica was formed as the administrative capital. The remaining territory was left in the domain of the Numidian client king Massinissa. At this time, the Roman policy in Africa was simply to prevent another great power from rising on the far side of Sicily.

In 118 BC, the Numidian prince Jugurtha attempted to reunify the smaller kingdoms. However, upon his death, much of Jugurtha's territory was placed in the control of the Mauretanian client king Bocchus; and, by that time, the romanization of Africa was firmly rooted. In 27 BC, when the Republic had transformed into an Empire, the province of Africa began its Imperial occupation under Roman rule.

Several political and provincial reforms were implemented by Augustus and later by Caligula, but Claudius finalized the territorial divisions into official Roman provinces. Africa was a senatorial province. After Diocletian's administrative reforms, it was split into Africa Zeugitana (which retained the name Africa Proconsularis, as it was governed by a proconsul) in the north and Africa Byzacena in the south, both of which were part of the Dioecesis Africae.

The region remained a part of the Roman Empire until the Germanic migrations of the 5th century. The Vandals crossed into North Africa from Spain in 429 and overran the area by 439 and founded their own kingdom, including Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearics. The Vandals controlled the country as a warrior-elite. They also persecuted Catholicism, as the Vandals were adherents of Arianism (the semi-trinitarian doctrines of Arius, a priest of Egypt). Towards the end of the 5th century, the Vandal state fell into decline, abandoning most of the interior territories to the Mauri and other Berber tribes of the desert.

In AD 533, Emperor Justinian, using a Vandal dynastic dispute as pretext, sent an army under the general Belisarius to recover Africa. In a short campaign, Belisarius defeated the Vandals, entered Carthage in triumph and re-established Roman rule over the province. The restored Roman administration was successful in fending off the attacks of the Amazigh desert tribes, and by means of an extensive fortification network managed to extend its rule once again to the interior.

The North African provinces, together with the Roman possessions in Spain, were grouped into the Exarchate of Africa by Emperor Maurice. The exarchate prospered, and from it resulted the overthrow of the emperor Phocas by Heraclius in 610. Heraclius briefly considered moving the imperial capital from Constantinople to Carthage.

After 640, the exarchate managed to stave off the Muslim Conquest, but in 698, a Muslim army from Egypt sacked Carthage and conquered the exarchate, ending Roman and Christian rule in North Africa.

Timetable

| EVOLUTION OF THE PROVINCE OF AFRICA | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-Roman Conquest | Carthage | Eastern Numidia (Massylii) | Western Numidia (Masaesyli) | Mauretania | ||||

| by 146 BC | Africa | Numidia | Mauretania | |||||

| by 105 BC | Africa | Eastern Numidia | Western Numidia | Mauretania | ||||

| by 45 BC | Africa Vetus | Africa Nova | Western Numidia | Eastern Mauretania | Western Mauretania | |||

| by 27 BC | Africa Proconsularis | Mauretania | ||||||

| by 41 AD | Africa Proconsularis | Mauretania Caesariensis | Mauretania Tingitana | |||||

| by 193 AD | Africa Proconsularis | Numidia | Mauretania Caesariensis | Mauretania Tingitana | ||||

| by 314 AD | Tripolitania | Africa Byzacena | Africa Zeugitana | Numidia | Mauretania Sitifensis | Mauretania Caesariensis | Mauretania Tingitana | |

- Legend

Roman Africans

The African province was amongst the wealthiest regions in the Empire (rivaled only by Egypt, Syria and Italy itself) and as a consequence people from all over the Empire migrated into the Roman Africa Province, most importantly veterans in early retirement who settled in Africa on farming plots promised for their military service. Historian Theodore Mommsen estimated that under Hadrian nearly 1/3 of the eastern Numidia population (roughly modern Tunisia) was descended from Roman veterans.[1]

Even so, the Roman military presence of North Africa was relatively small, consisting of about 28,000 troops and auxiliaries in Numidia and the two Mauretanian provinces. Starting in the 2nd century AD, these garrisons were manned mostly by local inhabitants. A sizable Latin speaking population developed that was multinational in background, sharing the north African region with those speaking Punic and Berber languages.[1][2] Imperial security forces began to be drawn from the local population, including the Berbers.

Abun-Nasr, in his A History of the Maghrib, said that "What made the Berbers accept the Roman way of life all the more readily was that the Romans, though a colonizing people who captured their lands by the might of their arms, did not display any racial exclusiveness and were remarkably tolerant of Berber religious cults, be they indigenous or borrowed from the Carthaginians. However, the Roman territory in Africa was unevenly penetrated by Roman culture. Pockets of non-Romanized Berbers continued to exist throughout the Roman period, even in such areas as eastern Tunisia and Numidia."

By the end of the Western Roman Empire nearly all of the Maghreb was fully romanized, according to Mommsen in his The Provinces of the Roman Empire and the Roman Africans enjoyed a high level of prosperity. This prosperity (and romanization) touched partially even the populations living outside the Roman limes (mainly the Garamantes and the Getuli), who were reached with Roman expeditions to Sub-Saharan Africa.

The willing acceptance of Roman citizenship by members of the ruling class in African cities produced such Roman Africans as the comic poet Terence, the rhetorician Fronto of Cirta, the jurist Salvius Julianus of Hadrumetum, the novelis Apuleius of Madauros, the emperor Septimius Severus of Lepcis Magna, the Christians Tertullian and Cyprian of Carthage, and Arnobius of Sicca and his pupil Lactantius; the angelic doctor Augustine of Thagaste, the epigrammatist Luxorius of Vandal Carthage, and perhaps the biographer Suetonius, and the poet Dracontius.— Paul MacKendrick, The North African Stones Speak (1969), UNC Press, 2000, p.326

Economics

The prosperity of most towns depended on agriculture. Called the "granary of the empire", North Africa, according to one estimate, produced one million tons of cereals each year, one-quarter of which was exported. Additional crops included beans, figs, grapes, and other fruits. By the 2nd century, olive oil rivaled cereals as an export item. In addition to the cultivation of slaves, and the capture and transporting of exotic wild animals, the principal production and exports included the textiles, marble, wine, timber, livestock, pottery such as African Red Slip, and wool.

The incorporation of colonial cities into the Roman Empire brought an unparalleled degree of urbanization to vast areas of territory, particularly in North Africa. This level of rapid urbanization had a structural impact on the town economy, and artisan production in Roman cities became closely tied to the agrarian spheres of production. As Rome's population grew, so did her demand for North African produce. This flourishing trade allowed the North African provinces to increase artisan production in rapidly developing cities, making them highly organized urban centers. Many Roman cities shared both consumer and producer model city aspects, as artisanal activity was directly related to the economic role cities played in long-distance trade networks.[3]

The urban population became increasingly engaged in the craft and service sectors and less in agrarian employment, until a significant portion of the town’s vitality came from the sale or trade of products through middlemen to markets in areas both rural and abroad. The changes that occurred in the infrastructure for agricultural processing, like olive oil and wine production, as trade continued to develop both cities and commerce directly influenced the volume of artisan production. The scale, quality, and demand for these products reached its acme in Roman North Africa.[3]

Pottery production

The North African provinces spanned across regions rich with olive plantations and potters' clay sources, which led to the early development of fine Ancient Roman pottery, especially African Red Slip terra sigillata tableware and clay oil lamp manufacture, as a crucial industry. Lamps provided the most common form of illumination in Rome. They were used for public and private lighting, as votive offerings in temples, lighting at festivals, and as grave goods. As the craft developed and increased in quality and craftsmanship, the North African creations began to rival their Italian and Grecian models and eventually surpassed them in merit and in demand.[4]

The innovative use of molds around the 1st century BC allowed for a much greater variety of shapes and decorative style, and the skill of the lamp maker was demonstrated by the quality of the decoration found typically on the flat top of the lamp, or discus, and the outer rim, or shoulder. The production process took several stages. The decorative motifs were created using small individual molds, and were then added as appliqué to a plain archetype of the lamp. The embellished lamp was then used to make two plaster half molds, one lower half and one upper half mold, and multiple copies were then able to be mass-produced. Decorative motifs ranged according to the lamp's function and to popular taste.[4]

Ornate patterning of squares and circles were later added to the shoulder with a stylus, as well as palm trees, small fish, animals, and flower patterns. The discus was reserved for conventional scenes of gods, goddesses, mythological subjects, scenes from daily life, erotic scenes, and natural images. The strongly Christian identity of post-Roman society in North Africa is exemplified in the later instances of North African lamps, on which scenes of Christian images like saints, crosses, and biblical figures became commonly articulated topics. Traditional mythological symbols had enduring popularity as well, which can be traced back to North Africa's Punic heritage. Many of the early North African lamps that have been excavated, especially those of high quality, have the name of the manufacturer inscribed on the base, which gives evidence of a highly competitive and thriving local market that developed early and continued to influence and bolster the colonial economy.[4]

African Terra Sigillata

After a period of artisanal, political, and social decline in the 3rd century AD, lamp-making revived and accelerated artistry in the early Christian age to new heights. The introduction of fine local red-fired clays in the late 4th century triggered this revival. African Red Slip ware (ARS), or African Terra Sigillata, revolutionized the pottery and lamp-making industry.[5]

ARS ware was produced from the last third of the 1st century AD onwards, and was of major importance in the mid-to-late Roman periods. Famous in antiquity as "fine" or high-quality tableware, it was distributed both regionally and throughout the Mediterranean basin along well-established and heavily trafficked trade routes. North Africa's economy flourished as its products were dispersed and demand for its products dramatically increased.[6]

Initially, the ARS lamp designs imitated the simple design of 3rd- to 4th-century courseware lamps, often with globules on the shoulder or with fluted walls. But new, more ornate designs appeared before the early 5th century as demand spurred on the creative process. The development and widespread distribution of ARS finewares marks the most distinctive phase of North African pottery-making.[7]

These characteristic pottery lamps were produced in large quantities by efficiently organized production centers with large-scale manufacturing abilities, and can be attributed to specific pottery-making centers in northern and central Tunisia by way of modern chemical analysis, which allows modern archeologists to trace distribution patterns among trade routes both regional and across the Mediterranean.[6] Some major ARS centers in central Tunisia are Sidi Marzouk Tounsi, Henchir el-Guellal (Djilma), and Henchir es-Srira, all of which have ARS lamp artifacts attributed to them by the microscopic chemical makeup of the clay fabric as well as macroscopic style prevalent in that region.

This underscores the idea that these local markets fueled the economy of not only the town itself, but the entire region and supported markets abroad. Certain vessel forms, fabrics, and decorative techniques like rouletting, appliqué, and stamped décor, are specific for a certain region and even for a certain pottery center. If neither form nor decoration of the material to be classified is identifiable, it is possible to trace its origins, not just to a certain region but even to its place of production by comparing its chemical analysis to important northeastern and central Tunisian potteries with good representatives.

Governors of Roman Africa

Republican era

Unless otherwise noted, names of governors in Africa and their dates are taken from T.R.S. Broughton, The Magistrates of the Roman Republic, (New York: American Philological Association, 1951, 1986), vol. 1, and vol. 2 (1952).

146–100 BC

Inscriptional evidence is less common for this period than for the Imperial era, and names of those who held a provincia are usually recorded by historians only during wartime or by the triumphal fasti. After the defeat of Carthage in 146 BC, no further assignments to Africa among the senior magistrates or promagistrates are recorded until the Jugurthine War (112–105 BC), when the command against Jugurtha in Numidia became a consular province.

- P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (146 BC)

- L. Calpurnius Bestia (111 BC)

- Sp. Postumius Albinus (110–109 BC)[8]

- Q. Caecilius Metellus Numidicus (109–107 BC)[9]

- C. Marius (107–105 BC)

- L. Cornelius Sulla (105 BC)[10]

90s–31 BC

During the civil wars of the 80s and 40s BC, legitimate governors are difficult to distinguish from purely military commands, as rival factions were vying for control of the province by means of force.

- None known with reasonable certainty for the 90s

- P. Sextilius (88–87 BC)

- Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius (86–84 BC)

- C. Fabius Hadrianus (84–82 BC)

- Gn. Pompeius Magnus (82–79 BC)

- L. Licinius Lucullus (77–76/75 BC)

- A. Manlius Torquatus (69 BC or earlier)

- L. Sergius Catilina (67–66 BC)

- Q. Pompeius Rufus (62–60/59 BC)

- T. Vettius, cognomen possibly Sabinus (58–57 BC)

- Q. Valerius Orca (56 BC)

- P. Attius Varus (52 BC and probably earlier; see also below)

- C. Considius Longus (51–50 BC)

- L. Aelius Tubero (49 BC; may never have assumed the post)

- P. Attius Varus (seized control again in 49 and held Africa until 48)

- Q. Caecilius Metellus Pius Scipio Nasica (47 BC)

- M. Porcius Cato (jointly in 47 BC with special charge of Utica)

- C. Caninius Rebilus (46 BC)

- C. Calvisius Sabinus (45–early 44 BC, Africa Vetus)

- C. Sallustius Crispus, the historian usually known in English as Sallust (45 BC, Africa Nova)

- Q. Cornificius (44–42 BC, Africa Vetus)

- T. Sextius (44–40 BC, Africa Nova)

- C. Fuficius Fango (41 BC)

- M. Aemilius Lepidus (40–36 BC)

- T. Statilius Taurus (35 BC)

- L. Cornificius (34–32 BC)

Imperial era

Principate

Reign of Augustus

- Lucius Autronius Paetus (29/28 BC)[11]

- Marcus Acilius Glabrio (25 BC)[11]

- Lucius Sempronius Atratinus (?c. 21/20 BC)[11]

- Lucius Cornelius Balbus (20/19 BC)[11]

- Gaius Sentius Saturninus (14/13 BC)[11]

- Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus (13/12 BC)

- Publius Quinctilius Varus approx (9/8–4 BC)

- Lucius Passienus Rufus approx (c. AD 4/5)

- Cossus Cornelius Lentulus Gaetulicus (c. AD 5/6)

- Lucius Caninius Gallus (c. AD 8)

- Lucius Nonius Asprenas[12] (14–15)

Reign of Tiberius

- Lucius Aelius Lamia (15–16)

- Marcus Furius Camillus[13] (17–18)

- Lucius Apronius[14] (18–21)

- Quintus Junius Blaesus[15] (21–23)

- Publius Cornelius Dolabella[16] (23–24)

- Gaius Vibius Marsus (26–29)

- Marcus Junius Silanus (29–35)

- Gaius Rubellius Blandus (35–36)

- Servius Cornelius Cethegus (36–37)

Reign of Gaius Caligula

- Lucius Calpurnius Piso (38–39)

- Lucius Salvius Otho (40–41)

Reign of Claudius

- Quintus Marcius Barea Soranus (41–43)

- Servius Sulpicius Galba (44–46)

- Marcus Servilius Nonianus (46–47)

- Titus Statilius Taurus IV[17] (52–53)

- Marcus Pompeius Silvanus Staberius Flavianus (53–56)

Reign of Nero

- Quintus Sulpicius Camerinus Peticus (56–57)

- Gnaeus Hosidius Geta (57–58)

- Quintus Curtius Rufus[18] (58–59)

- Aulus Vitellius (60–61)

- Lucius Vitellius (61–62)

- Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus (62–63)

- Titus Flavius Vespasianus (63–64)

- Gaius Vipstanus Apronianus (68)

Reign of Vespasian

- Lucius Calpurnius Piso (69/70)[19]

- Lucius Junius Quintus Vibius Crispus (71/72)

- Quintus Manlius Ancharius Tarquitius Saturninus (72/73)

- Quintus Julius Cordinus Gaius Rutilius Gallicus (74)

- Gaius Paccius Africanus (77/78)

- Publius Galerius Trachalus (78/79)

Reign of Domitian

- Lucius Nonius Calpurnius Asprenas (82/83)

- Sextus Vettulenus Cerialis (83/84)

- Gnaeus Domitius Lucanus (84/85)

- Gnaeus Domitius Tullus (85/86)

- Lucius Funisulanus Vettonianus (91/92)

- Asprenas (92/93)

Reign of Nerva

- Marius Priscus (97/98)

Reign of Trajan

- Gaius Cornelius Gallicanus (98/99)

- Gaius Octavius Tidius Tossianus Lucius Javolenus Priscus (101/102)

- Lucius Cornelius Pusio Annius Messala (103/104)

- Quintus Peducaeus Priscinus (106/107)

- Gaius Cornelius Rarus Sextius Naso (108/109)

- Quintus Pomponius Rufus (110/111)

- Gaius Pomponius Rufus Acilius Priscus Coelius Sparsus (112/113)

- Aulus Caecilius Faustinus (115/116)

- Gaius Julius Plancus Varus Cornutus Tertullus (116/117)

Reign of Hadrian

- Lucius Roscius Aelianus Maecius Celer (117/118)

- Marcus Vitorius Marcellus (120/121)

- Lucius Minicius Natalis (121/122)

- Lucius Catilius Severus Julianus Claudius Reginus (124/125)

- Lucius Stertinius Noricus (127/128)

- Marcus Pompeius Macrinus (130/131)

- Tiberius Julius Secundus (131/132)

- Gaius Ummidius Quadratus Sertorius Severus (133/134)

- Gaius Bruttius Praesens Lucius Fulvius Rusticus (134/135)

- [...]catus P. Valerius Priscus (136/137)

- Lucius Vitrasius Flamininus (137/138)

- Titus Salvius Rufinus Minicius Opimianus (138/139)

Reign of Antoninus Pius

- Titus Salvius Rufinus Minicius Opimianus (138–139)[20]

- Titus Prifernius Paetus Rosianus Geminus (140–141)[21]

- Sextus Julius Major (c. 141–142)

- Publius Tullius Varro (142–143)

- Lucius Minicius Natalis Quadronius Verus (153–154)

- (? Ennius) Proculus (156–157)

- Lucius Hedius Rufus Lollianus Avitus (157–158)

- Claudius Maximus (c. 158–159)

- Quintus Egrilus Plarianus Lucius M[...] (c. 159)

Reign of Marcus Aurelius

- Titus Prifernius Paetus Rosianus Geminus (c. 160–161)

- Quintus Voconius Saxa Fidus (161–162)

- Sextus Cocceius Severianus (c. 162–163)

- Servius Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orfitus (164)

- Manius Acilius Glabrio Gnaeus Cornelius Severus (c. 166–167)

- Publius Salvius Julianus (167–168)

- Titus Sextius Lateranus (168/169)

- Gaius Serius Augurinus (169–170)

- Strabo Aemilius (c. 172)

- Gaius Aufidius Victorinus (c. 173–174)

- Gaius Septimus Severus (174–175)

- Publius Julius Scapula Tertullus (178–179 or 179–180)

- Publius Vigellius Saturninus[22] (c. 180)

Reign of Commodus

Reign of Septimius Severus

- Publius Cornelius Anullinus (193)[23]

- Pollienus Auspex (Between 194 and 200)

- Marcus Claudius Macrinius Vindex Hermogenianus (Between 194 and 200)

- Sextus Cocceius Vibianus (Between 194 and 200)

- Cingius Severus (Between 194 and 197)

- Lucius Cossonius Eggius Marullus (198–199)

- Marcus Ulpius Arabianus (c. 200)

- Gaius Julius Asper (Between 200 and 210)

- Marcus Umbrius Primus (c. 201/2)

- Minicius Opimianus (c. 203)

- Rufinus (c. 204)

- Marcus Valerius Bradua Mauricus (? c. 206)

- Titus Flavius Decimus (209)

- Gaius Valerius Pudens (Between 209 and 211)

Reign of Caracalla

- Publius Julius Scapula Tertullus Priscus (212–213)

- Appius Claudius Julianus (Between 212 and 220)

- Gaius Caesonius Macer Rufinianus (Between 213 and 215)

- Marius Maximus (Between 213 and 217)

Reign of Elagabalus

- Lucius Marius Perpetuus (c. 220)

- Lucius Cassius Dio Cocceianus (c. 221)

Reign of Alexander Severus

Reign of Maximinus Thrax

Reign of Gordian III

- Sabinianus (240)

- Lucius Caesonius Lucillus Macer Rufinianus (c. 240)

Reigns of Valerian and Gallienus

- Aspasius Paternus (257–258)

- Galerius Maximus (258–259)

- Lucius Messius [...] (Between 259 and 261)

- ? Vibius Passienus (Between 260 and 268)

- Lucius Naevius Aquilinus (Between 260 and 268)

- Sextus Cocceius Anicius Faustus (Between 265 and 268)

Reign of Aurelian

- Firmus (278)

- Lucius Caesonius Ovinius Manlius Rufinianus Bassus (c. 275)

Reign of Carinus

- Gaius Julius Paulinus (283)

Later Empire

Governors are directly chosen by the Emperors, without Roman Senate approval.

- Titus Claudius Aurelius Aristobulus (290–294)

- Cassius Dio (294–295)

- Titus Flavius Postumius Titianus (295–296)

- Lucius Aelius Helvius Dionysius (296–300)

- Iulianus, possibly Amnius Anicius Julianus (301–302)

- Gaius Annius Anullinus (302–305)

- Gaius Caeionius Rufius Volusianus (305–306)

- Petronius Probianus (315–317)

- Aconius Catullinus (317–318)

- Cezeus Largus Maternianus (333-336)[24]

- Quintus Flavius Maesius Egnatius Lollianus (336-337)

- Antonius Marcellinus (337-338)

- Aurelius Celsinus (338-339)

- Fabius Aconius Catullinus Philomathius (vicarius, 338–339)

- Proculus (340-341)

- -lius Flavianus (357-358)

- Sextus Claudius Petronius Probus (358-359)

- Proclianus (359-361)

- Quintus Clodius Hermogenianus Olybrius (361-362)

- Clodius Octavianus (363-364)

- P. Ampelius (364-365)

- ?Claudius Hermogenianus Caesarius (365-366)

- Julius Festus Hymetius (366-368)[25]

- Petronius Claudius (368-371)

- Sextius Rusticus Julianus (371-373)

- Quintus Aurelius Symmachus (373-374)

- Paulus Constantius (374-375)

- Chilo (375-376)

- Decimius Hilarianus Hesperius (April 376-October 377)

- Thalassius (October 377-April 379)

- Flavius Afranius Syagrius (379-380)

- Helvius Vindicianus (380-381; possibly 382-383)

- Herasius (381-382)

- Virius Audentius Aemilianus (382-383; possibly 381-382)

- Flavius Eusignius (383-384)

- Messianus (385-386)

- Felix Juniorinus Polemius (388-389)

- Latinius Pacatus Drepanius (389-390)

- Flavius Rhodinus Primus (391-392)

- Aemilius Florus Paternus (392-393)[26]

- Flaccianus (393-393)

- Marcianus (394)

- Flavius Herodes (394-395)

- Ennodius (395-396)

- Theodorus (396-397)

- Anicius Probinus (397)[27]

- Seranus (397-398)

- Victorinus (398-399)

- Apollodorus (399-400)

- Gabinius Barbarus Pompeianus (400–401)

- Helpidius (401-402 ?)

- Septiminus (402-404)

- Rufius Antonius Agrypnius Volusianus (404-405)

- Flavius Pionius Diotimus (405-406)

- C. Aelius Pompeius Porphyrius Proculus (407-408)

- Donatus (408-409)

- Macrobius Palladius (409-410)

- Apringius (410-411)

- Eucharius (411-412)

- Q. Sentius Fabricius Iulianus (412-414)

- Aurelius Anicius Symmachus (415)[28]

Episcopal sees

Ancient episcopal sees of Proconsular Africa listed in the Annuario Pontificio as titular sees:[29]

- Abbir Germaniciana

- Abbir Maius (Henchir-en-Naam)

- Abitinae

- Abora

- Absa Salla

- Abthugni (Henchir-Casbat-Es-Souar)

- Abziri (near Oudna)

- Agbia (Aïn-Hedia in Tunisia), suffragan of Carthage

- Altiburus (Henchir-Medeina, Dahmani)

- Apisa Maius (ruins of Targ-Ech-Chena)

- Aptuca (Henchir-Oudeca)

- Aquae in Proconsulari (Henchir-El-Baghla)

- Aquae Novae in Proconsulari (ruins of Sidi-Ali-Djebin?)

- Aradi (Henchir-Bou-Arada?)

- Assuras

- Ausana

- Ausuaga

- Avensa (ruins of Bordj-Hamdouna)

- Avioccala (ruins of Sidi-Amara)

- Avissa (Henchir-Bour-Aouitta, Aouïa?)

- Avitta Bibba

- Belali (Henchir-Belli)

- Bencenna (ruins of Sidi-Brahim)

- Beneventum (Africa) (ruins of Beniata?)

- Bilta (ruins of Sidi-Salah-El-Balthi?)

- Bisica (Henchir-Bijga)

- Bita

- Bitettum (Bitetto)

- Bonusta

- Boseta (ruins of Henchir-El-Oust?)

- Bossa

- Botriana

- Bulla (ruins of Sidi-Mbarec)

- Bulla Regia

- Bulna

- Bure

- Buruni (Henchir-El-Dakhla)

- Buslacena

- Caeciri

- Canapium (Henchir-El-Casbath)

- Carpi (Henchir-Mraïssa)

- Carthage (episcopal see), the Metropolitan Archdiocese, exercising informal primacy

- Cefala (Ras-El-Djebel?)

- Cellae in Proconsulari (ruins of Aïn-Zouarin)

- Cerbali

- Cilibia (Henchir-Kelbia)

- Cincari (ruins of Bordj-Toum)

- Cissita (Sidi-Tabet?)

- Clypia (Kelibia)

- Cresima (Aïn-Sbir?)

- Cubda

- Culusi (suburb of Carthage)

- Curubis (Korba, Tunisia)

- Drusiliana (Khanguet-El-Kidem)

- Eguga

- Elephantaria in Proconsulari (Sidi-Ahmed-Djedidi? ruins of Sidi-Saïd?)

- Enera

- Furnos Maior

- Furnos Minor

- Gisipa

- Giufi (Bir-Mecherga)

- Giufi Salaria (near the saltworks of Sebkha-El-Coursia)

- Gor (Drâa-El-Gamra)

- Gummi in Proconsulari (Bordj-Cedria)

- Gunela

- Hilta

- Hippo Diarrhytus

- Horta (in the territory of Srâ-Orta?)

- Lacubaza

- Lapda

- Lares (Lorbeus)

- Libertina (ruins at Souc-El-Arba?)

- Luperciana (Henchir-Tebel? or ruins of Gasseur-Tatoun?)

- Marcelliana (in the region of Henchir-Bez)

- Mathara in Proconsulari (Mateur)

- Mattiana

- Maxula Prates (Radès)

- Medeli (Henchir-Mencoub)

- Megalopolis in Proconsulari (ruins of Mohammedia)

- Melzi (ruins where the Oued-Melzi flows into the Bagrada)

- Membressa (Majaz al Bab)

- Migirpa (near Carthage)

- Missua (Sidi Daoud)

- Mizigi (ruins of Douela)

- Mulli

- Musti

- Muzuca in Proconsulari (Henchir-Khachoum)

- Naraggara

- Neapolis in Proconsulari (Nabeul)

- Nova

- Numluli (Henchir-Mâtria)

- Obba

- Paria in Proconsulari

- Pertusa (El-Haraïria)

- Pia

- Pisita (ruins of Bou-Chateur-Sidi-Mansour?)

- Pocofeltus

- Pupiana (Mra-Mita, Aïn-Ouassel?)

- Puppi

- Rucuma

- Rusuca (Ghar al Milh?)

- Saia Maior (Henchir-Duamès-Chiaïa, Henchir-Chiaïa)

- Scilium

- Sebarga

- Selamselae

- Semina

- Semta (Dzemda)

- Serra (Henchir-Cherri)

- Sicca Veneria

- Siccenna

- Sicilibba (ruins of Alaouine, Alaouenine)

- Simidicca (Henchir-Simidia?)

- Simingi (Henchir-Simindja, Sidi Bou Zid)

- Siminina (Henchir-El-Haïrech, Bir-El-Djedidi)

- Simitthu (Chemtou)

- Sinna (ruins of Calaat-Es-Sinân)

- Sinnuara

- Sitipa

- Suas (ruins of Chaouach)

- Succuba

- Sululos

- Sutunura (ruins of Aïn-El-Askerm Rdir-Es-Soltan)

- Tabbora

- Tacia Montana (ruins of Bordj-Messaoudi)

- Taddua

- Tagarata (ruins of Tel-El-Caid, Aïn-Tlit?)

- Teglata (Henchir Kahloulta)

- Tela (in the region of Carthage)

- Tepela (Henchir-Bel-Aït)

- Thabraca

- ? Thapsus (in Byzacena?!)

- Theudalis (Henchir-Aouam)

- Thibaris

- Thibica (Bir-Magra)

- Thibiuca (Henchir-Gâssa)

- Thignica

- Thisiduo (ruins of Crich-El-Oued)

- Thimida (Henchir-Tindja)

- Thizica

- Thuburbo Maius

- Thuburbo Minus

- Thuburnica (Sidi-Ali-Bel-Cassem)

- Thubursicum-Bure (Téboursouk)

- Thuccabora (Touccabeur)

- Thugga

- Thunigaba (Henchir-Aïn-Laabed)

- Thunusruma

- Thunusuda (Sidi-Meskin)

- Tigimma (Souk-El-Djemma, Djemâa?)

- Tinisa in Proconsulari (Râs-El-Djebel)

- Tisili

- Tituli in Proconsulari (Henchir-Madjouba)

- Trisipa (Aïn-El-Hammam)

- Tubernuca (Aïn Tebernoc)

- Tubyza (Henchir-Boucha?)

- Tulana

- Tunes

- Turris in Proconsulari (in the territory of Henchir-Mest)

- Turuda

- Turuzi

- Uccula (Henchir-Aïn-Dourat)

- Uchi Maius (Henchir-Ed-Douamès)

- Ucres (Bordj-Bou-Djadi)

- Ululi (Ellez?)

- Urusi (Henchir-Sougda)

- Uthina

- Utica

- Utimma (between Sidi-Medien and Henchir-Reoucha?)

- Utimmira (in the territory of Carthage)

- Uzalis

- Uzzipari

- Vaga (Béja)

- Vallis (ruins of Sidi-Medien)

- Vazari (Henchir-Bejar, Bedjar)

- Vazari-Didda (Henchir-Badajr?)

- Vazi-Sarra (Henchir-Bez)

- Vertara (region of Srâa Ouartane)

- Vicus Turris (Henchir-El-Djemel)

- Villamagna in Proconsulari (Henchir-Mettich)

- Vina (Henchir-El-Meden)

- Vinda (Henchir-Bandou?)

- Voli

- Zama Major

- Zama Minor

- Zarna

- Zica (Zaghouan?)

- Zuri (Aïn Djour? in the region of Carthage?)

See also

- African Romance

- Lex Manciana

- Praetorian prefecture of Africa

- Fossatum Africae

- Roman limes

- Roman roads in Africa

Notes

- 1 2 Abun-Nasr, A History of the Maghrib (1970, 1977) at 35-37.

- ↑ Laroui challenges the accepted view of the prevalence of the Latin language, in his The History of the Maghrib (1970, 1977) at 45-46.

- 1 2 Wilson, A. I., 2002. Papers of the British School at Rome. Vol 70, Urban Production in the Roman World: The View from North Africa. London: British School at Rome. 231-73.

- 1 2 3 Brouillet, Monique Seefried., ed. 1994. From Hannibal to Saint Augustine: Ancient Art of North Africa from the Musee Du Louvre, 82-83, 129-130. Atlanta: Emory University.

- ↑ Brouillet, Monique Seefried., ed. 1994. From Hannibal to Saint Augustine: Ancient Art of North Africa from the Musee Du Louvre, 129-130. Atlanta: Emory University.

- 1 2 Mackensen, Michael and Gerwulf Schneider. 2006. “Production centres of African Red Slip Ware (2nd-3rd c.) in northern and central Tunisia: Archaeological provenance and reference groups based on chemical analysis.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 19: 163-188.

- ↑ Brouillet, Monique Seefried., ed. 1994. From Hannibal to Saint Augustine: Ancient Art of North Africa from the Musee Du Louvre, 129. Atlanta: Emory University.

- ↑ Continued as proconsul until the arrival of Metellus in 109 BC.

- ↑ Continued as proconsul until the arrival of his successor Marius, whom he declined to meet for the transfer of command. He triumphed over Numidia in 106 and received his cognomen Numidicus at that time.

- ↑ Delegated command pro praetore when Marius returned to Rome.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ronald Syme, The Augustan Aristocracy (Clarendon Press, 1986), p. 45 n 80

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals I.53

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals II.52

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.21

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals III.35, III.58

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals IV.23

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals XII.59

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals XI.21

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the names of the proconsular governors from 69 to 139 are taken from Werner Eck, "Jahres- und Provinzialfasten der senatorischen Statthalter von 69/70 bis 138/139", Chiron, 12 (1982), pp. 281-362; 13 (1983), pp. 147-237

- ↑ Identified by Werner Eck, "Ergänzungen zu den Fasti Consulares des 1. und 2. Jh.n.Chr.", Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte, 24 (1975), pp. 324-344, esp. pp. 324-6

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the names of the proconsular governors from 139 to 180 are taken from Géza Alföldy, Konsulat und Senatorenstand unter der Antoninen (Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag, 1977), pp. 207-211

- ↑ Alföldy, Konsulat und Senatorenstand, pp. 365-367

- ↑ Mennen, Inge, Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284 (2011), pg. 261

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the names of the proconsular governors from 333 to 392 are taken from the list in T.D. Barnes, "Proconsuls of Africa, 337-392", Phoenix, 39 (1985), pp. 144-153

- ↑ Per the list provided in T.D. Barnes, "Proconsuls of Africa: Corrigenda", Phoenix, 39 (1985), pp. 273-274

- ↑ Unless otherwise stated, the names of the proconsular governors from 392 to 414 are taken from the list T.D. Barnes, "Late Roman Prosopography: Between Theodosius and Justinian", Phoenix, 37 (1983), pp. 248-270

- ↑ In 396 Quintus Aurelius Symmachus wrote him a letter (Epistulae, ix); on 17 March 397 he received a law preserved in the Codex Theodosianus (XII.5.3).

- ↑ During this office he received the law preserved in Codex Theodosianus, xi.30.65a.

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice Vaticana, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), "Sedi titolari", pp. 819-1013

References

- Lennox Manton, Roman North Africa, 1988.

- Susan Raven. Rome in Africa. 3rd ed. (London, 1993).

- Monique Seefried Brouillet, From Hannibal to Saint Augustine: Ancient Art of North Africa from the Musee du Louvre, 1994.

- A. I. Wilson, Urban Production in the Roman World: The View from North Africa, 2002.

- Duane R. Roller, The World of Juba II and Kleopatra Selene: Royal Scholarship on Rome's African Frontier (New York and London, Routledge, 2003).

- Elizabeth Fentress, "Romanizing the Berbers," Past & Present, 190,1 (2006), 3-33.

- Michael Mackensen and Gerwulf Schneider. Production centres of African Red Slip Ware (2nd-3rd c.) in northern and central Tunisia: Archaeological provenance and reference groups based on chemical analysis, 2006.

- Cordovana, Orietta Dora, Segni e immagini del potere tra antico e tardoantico: I Severi e la provincia Africa proconsularis. Seconda edizione rivista ed aggiornata (Catania: Prisma, 2007) (Testi e studi di storia antica)

- Dick Whittaker, "Ethnic discourses on the frontiers of Roman Africa", in Ton Derks, Nico Roymans (ed.), Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition (Amsterdam, Amsterdam University Press, 2009) (Amsterdam Archaeological Studies, 13), 189-206.

- Erich S. Gruen, Rethinking the Other in Antiquity (Princeton, PUP, 2010), 197-222.

- Mennen, Inge, Power and Status in the Roman Empire, AD 193-284 (2011)

- Stewart, John, African states and rulers (2006)