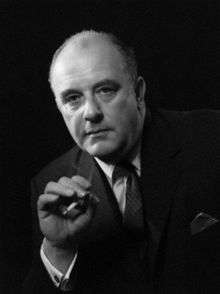

Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild

| The Right Honourable The Lord Rothschild GBE GM FRS | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild 31 October 1910 |

| Died | 20 March 1990 (aged 79) |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild, GBE GM FRS[1] (31 October 1910 – 20 March 1990), was a British biologist, a cricketer, a wartime officer for the UK Security Service (MI5), a senior executive with Royal Dutch Shell and N M Rothschild & Sons, an advisor to the UK Heath and Thatcher governments, as well as a member of the prominent Rothschild family. Born into a Jewish family, in adult life Rothschild declared himself to be an atheist.[2]

Biography

Early life

Rothschild was the third child, and only son of Charles Rothschild and Rozsika Rothschild (née Edle von Wertheimstein). The family home was Tring Park Mansion. He had three sisters, Miriam (1908–2005) who became a distinguished entomologist, Nica (1913–1988), who became a patron of highly influential jazz musicians Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk, and Elizabeth, known as Liberty (1909–1988).

Rothschild suffered the suicide of his father, who suffered from encephalitis, in 1923, when he was 13 years old.

Rothschild was educated at Harrow School. Reflecting on his time there, he later wrote "being intellectually pre-cocious, no doubt unpleasantly so, I was frequently punished", recalling he was frequently beaten for being cheeky.[3]

Cambridge and London

At Trinity College, Cambridge, he read Physiology, French and English. While at Cambridge Rothschild was said to have a playboy lifestyle, enjoying waterskiing in Monaco, driving fast cars, collecting art and rare books and playing first-class cricket for the University and Northamptonshire.[4]

Rothschild joined the Cambridge Apostles, a secret intellectual society at the University. The society was essentially a discussion group. Meetings were held once a week, traditionally on Saturday evenings, during which one member gave a prepared talk on a topic, which was later thrown open for discussion. The society was at that time predominantly Marxist, though Rothschild stated that he "was mildly left-wing but never a Marxist".[5] He became friends with Guy Burgess, Anthony Blunt and Kim Philby; later exposed as members of the Cambridge Spy Ring.

In 1933 Rothschild gave Anthony Blunt £100 to purchase "Eliezer and Rebecca" by Nicolas Poussin.[6] The painting was sold by Blunt's executors in 1985 for £100,000[7] and is now in the Fitzwilliam Museum.[8]

Rothschild married Barbara Judith Hutchinson (1911-) in 1933, daughter of St John Hutchinson. They had three children together.[9]

In 1936 Rothschild bought the first of the Bugatti type 57 "Atlantic" sports car, of which only four were produced. The car featured flowing coupé lines with a pronounced dorsal seam running front to back, based on the "Aérolithe" concept car of 1935 styled by Jean Bugatti.[10] In 2010, after restoration, the car sold for over £19m to the Mullin Automotive Museum near Los Angeles.[11]

Rothschild inherited his title at the age of 26, following the death of his uncle Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild on 27 August 1937. He sat as a Labour Party peer in the House of Lords, but spoke only twice there during his life (both speeches were in 1946, one about the pasteurization of milk, and another about the situation in Palestine[12]).

World War II

In early 1939 Rothschild travelled to the United States where he visited the White House to discuss the issue of accepting Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany with Franklin D. Roosevelt and members of his cabinet.[13] This effort was unsuccessful, as soon after in May 1939 over 900 Jewish refugees aboard the MS St. Louis were denied access to the US and turned back to Europe.

In 1939 Rothschild was recruited to work for MI5, where he remained for the duration of World War II. He was attached to B division, under deputy director Guy Liddell, responsible for counter-espionage, with focuses such as "commercial espionage, sabotage, communications, censorship liaison, information leakage and examination of aliens".[14] In 1940 he produced a series of secret reports on "German Espionage Under cover of Commerce". In one such report on the machine tools industry, Rothschild advised "drastic action" to curtail "a system of espionage which is so extensive and so subtle and so difficult to combat" that it could prove "an important strategic factor in the conduct of the war".

Rothschild allowed Burgess and Blunt to live in his flat at 5 Bentinck Street in Westminster. In 1941 Teresa Georgina Mayor became Rothschild's secretary at MI5.[14]

Later, Rothschild founded section 'B1c' at Wormwood Scrubs, the wartime home of MI5.[15] This was an "explosives and sabotage section", and worked on identifying where Britain's war effort was vulnerable to sabotage, and countering German sabotage attempts. This included personally dismantling examples of German booby-traps and disguised explosives.[16] For this Rothschild won the George Medal in 1944 for "dangerous work in hazardous circumstances".[17] This involved dismantling a pair of German time bombs concealed in boxes of Spanish onions in Northampton.[14]

By late 1944 Rothschild was attached to the 105 Special Counter Intelligence Unit of the SHAEF, a joint operation of MI5 and X-2, the counter-espionage branch of OSS, a precursor of the CIA, operating in Paris.[14][18] Although initially based in a hostel of the YWCA, after ejecting US troops stationed there, Rothschild moved his headquarters to the former residence of his cousin Robert de Rothschild, at the Hôtel de Marigny.[13][19]

Cold War, Shell and Think Tank

In 1946, he married Teresa Georgina Mayor (1915–1996). Mayor's maternal grandfather was Robert John Grote Mayor, the brother of English novelist F. M. Mayor and a greatnephew of philosopher and clergyman John Grote. Her maternal grandmother, Katherine Beatrice Meinertzhagen, was the sister of soldier Richard Meinertzhagen and the niece of author Beatrice Webb.[20][21] They had four children:[9]

In 'Who paid the piper?' an account of CIA propaganda during the Cold War, author Frances Stonor Saunders alleges that Rothschild channelled funds to Encounter, an intellectual magazine founded in 1953 and edited by poet Stephen Spender and journalist Irving Kristol, to support the 'non-Stalinist left' in advance of US foreign policy goals.

After the war, he joined the zoology department at Cambridge University from 1950 to 1970. He served as chairman of the Agricultural Research Council from 1948 to 1958 and as worldwide head of research at Royal Dutch/Shell from 1963 to 1970.

Flora Solomon, a friend of Kim Philby and a well connected British Zionist, claims in her autobiography that in August 1962, during a reception at the Weizmann Institute, she told Rothschild that she thought that Tomás Harris and Kim Philby were Soviet spies.[22]

When Anthony Blunt was unmasked as a member of the Cambridge Spy ring in 1964, Rothschild was questioned by Special Branch (though Blunt was not publicly identified as a Soviet agent until 1979 in the House of Commons by Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher). Rothschild was cleared, and continued working on projects for the British government.[23]

Rothschild was head of the Central Policy Review Staff from 1971 to 1974 (known popularly as "The Think Tank")[24] a staff which researched policy specifically for the Government until Margaret Thatcher abolished it.

In 1971 Rothschild was awarded an honorary degree from Tel Aviv University for ''the advancement of science, education and the economy of Israel''. It was followed in 1975 by an honorary degree from Jerusalem's Hebrew university.[25] The annual 'Victor Rothschild Memorial Symposia' is named after Rothschild.

In 1976 Rothschild was succeeded as Chairman of N M Rothschild & Sons by his distant cousin Evelyn de Rothschild. In that year he also chaired the Royal Commission on Gambling.[26][27]

Rothschild published 'Meditations of a Broomstick', a collection of autobiographical notes and materials in 1977.[28]

Thatcher Years & Spycatcher

In the 1980s, he rejoined the family bank, N M Rothschild & Sons, as chairman in an effort to quell the feuding between factions led by Evelyn Rothschild and his son, Jacob Rothschild. In this he was unsuccessful as Jacob resigned from the bank to found J. Rothschild Assurance Group, a separate entity.

In 1982 he published An Enquiry into the Social Science Research Council at the behest of Sir Keith Joseph, a Conservative minister and mentor of Margaret Thatcher.[29]

He requested the role of security adviser to Margaret Thatcher at a dinner party held by Lady Avon in 1980 but was turned down.

He appears several times in the book Spycatcher written by Peter Wright, who he hoped would clear the air over suspicions about his wartime role. He was still able to enter the premises of MI5 as a former employee. He was aware of suspicions that there was a "Mole" in MI5 but he felt himself to be above suspicion. While Edward Heath was Prime Minister he was a frequent visitor to Chequers, the Prime Minister's country residence. Throughout his life he was a valued adviser on intelligence and science to both Conservative and Labour Governments.

Rothschild published an autobiography, 'Random Variables' in 1984.

Despite being an opposition Labour party peer, in 1987, during the Thatcher Government, Victor played a role in the sacking of BBC Director General Alasdair Milne, who had backed the programmes 'Secret Society', 'Real Lives',[30] and 'Panorama: Maggie's Militant Tendency' which had angered the Thatcher government. Marmaduke Hussey, who was Chairman of the BBC Board of Governors at the time, implied Rothchild initiated the Milne sacking in his autobiography Chance Governs All.[31]

Rothschild took the step of publishing a letter in The Daily Telegraph on 3 December 1986 to state that the "Director-General of MI5 should state publicly that he has unequivocal, repeat, unequivocal, evidence, that I am not, and never have been a Soviet agent". In a written statement, Margaret Thatcher confirmed that there was "no evidence that he was ever a Soviet agent".[32]

In early 1987 Tam Dalyell used parliamentary privilege to suggest Rothschild should be prosecuted for a chain of events he had "set in train, with Peter Wright and Harry Chapman Pincher" which had led to a "breach of confidence in relation to information on matters of state security given to authors".[33]

He was an advisor to William Waldegrave during the design of the Community Charge,[34] which led to the Poll Tax Riots.

In 1993, after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, six retired KGB colonels in Moscow including Yuri Modin, the spy ring's handler, alleged that Rothschild was the "Fifth Man" in the Cambridge Spy ring. Perry writes: "According to ... Modin, Rothschild was the key to most of the Cambridge ring's penetration of British intelligence. 'He had the contacts,' Modin noted. 'He was able to introduce Burgess, Blunt and others to important figures in Intelligence such as Stewart Menzies, Dick White and Robert Vansittart in the Foreign Office...who controlled Mi-6."[35] Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin's in the book The Mitrokhin Archives makes no mention made of Rothschild as a Soviet agent and instead identifies John Cairncross as the Fifth Man.

Descendants

With Barbara Judith Hutchinson:

- Sarah Rothschild (born 1934)[9]

- Nathaniel Charles Jacob Rothschild (born 1936) (later Jacob Rothschild) 4th Baron Rothschild[9]

- Miranda Rothschild (born 1940)[9]

With Teresa Georgina Mayor:

- Emma Georgina Rothschild (born 1948), married the Bengali Hindu economist Amartya Kumar Sen (b. 1933) in 1991.[9]

- Benjamin Mayer Rothschild (born and died 1952).[9]

- Victoria Katherine Rothschild (born 1953) is an academic lecturer at Queen Mary, University of London and the second wife and widow of English writer Simon Gray (1936–2008).[9]

- Amschel Mayor James Rothschild (1955–1996), married to Anita Patience Guinness of the Anglo-Irish Protestant Guinness family. Amschel committed suicide in 1996.[36] They had three children:

- Kate Emma Rothschild Goldsmith (b. 1982) who married Ben Goldsmith, the son of the late billionaire Sir James Goldsmith {of the Goldschmidt family} and Lady Annabel Goldsmith, in 2003 at St. Mary's Church in Bury St. Edmunds. They have three children: Iris Annabel (b. 2004), Frank James Amschel (b. 2005) and Isaac Benjamin Victor (b. 2008). In 2012, the couple announced that they were divorcing after it was alleged that Kate had an affair with American rapper Jay Electronica.[9][37]

- Alice Miranda Rothschild (b. 1983) is married to Zac Goldsmith, British Conservative Party politician, and the brother of her sister Kate's husband.[9][37]

- James Amschel Victor Rothschild (b. 1985)[9] is married to Nicky Hilton, second child and second daughter of Richard Hilton and his wife, née Kathy Avanzino, and a great-granddaughter of Conrad Hilton, who was the founder of Hilton Hotels.[38]

Honours and awards

Titles

- 3rd Baron Rothschild, of Tring in the County of Hertford [UK, 1885], 27 August 1937.[40]

- 4th Baronet Rothschild, of Tring Park [UK, 1847], 27 August 1937.[40]

Orders of Chivalry

- Knight Grand Cross, Order of the British Empire (GBE), 1975 New Year Honours.[41]

- Knight, Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem (KStJ).

- Knight, Sovereign Military Order of Malta.

Decorations

- George Medal (GM) (United Kingdom), 1944, "for dangerous work in hazardous circumstances"[42]

- Legion of Merit (United States), 1946.

- Bronze Star Medal (United States), 1948.

Fellowship of Learned Society

- Fellow, Royal Society (FRS), 1953.[43]

Military rank

- Major, Intelligence Corps.

Styles of address

- 1910–1937: Mr Victor Rothschild

- 1937–1944: The Right Honourable The Lord Rothschild[lower-alpha 1]

- 1944–1953: The Right Honourable The Lord Rothschild GM

- 1953–1975: The Right Honourable The Lord Rothschild GM FRS

- 1953–1990: The Right Honourable The Lord Rothschild GBE GM FRS

Notes

- ↑ Reeve, Suzanne (1994). "Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild, G.B.E., G.M., Third Baron Rothschild. 31 October 1910-20 March 1990". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 39: 364–326. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1994.0021.

- ↑ Wilson (1994), p. 466.

- ↑ Rothschild, Victor. Random Variables.

- ↑ "That Rothschild clan in full: eccentricity, money, influence and scandal | The Sunday Times". www.thesundaytimes.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ↑ Rose, Kenneth (2004). "Rothschild, (Nathaniel Mayer) Victor, third Baron Rothschild (1910–1990)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (revised ed.). Oxford University Press. Retrieved 9 March 2007.

- ↑ Rose (2003), pp. 47-48.

- ↑ "Eliezer and Rebecca by Nicolas Poussin". Art Fund. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ "Eliezer and Rebecca". Fitzwilliam Museum Collections. 2015. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "The descendants of Charles Rothschild" (PDF). The Rothschild Foster Trust. Retrieved 27 September 2012.

- ↑ Walter, Jamieson. "Bugatti Revue". Bugatti Revue. Retrieved April 2016. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Rothschild Archive :: Exhibitions ‹ Motoring Rothschilds". www.rothschildarchive.org. Retrieved 2016-04-04. horizontal tab character in

|title=at position 23 (help) - ↑ "Mr Nathaniel Rothschild (Hansard)". hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- 1 2 Rose, Kenneth (2003). The Elusive Rothschild. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 64, 83.

- 1 2 3 4 Costello, John (1988). Mask of Treachery. London: Collins. pp. 341, 369, 391, 422.

- ↑ Andrew, Christopher (2009). The Defence of the Realm. Allen Lane. p. 219.

- ↑ Macintyre, Ben (2007). Agent Zigzag : the true wartime story of Eddie Chapman. London: Bloomsbury. pp. 172–173. ISBN 9780747587941.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36452. p. 1548. 4 April 1944.

- ↑ "An SD Agent of Rare Importance (U)" (PDF).

- ↑ Muggeridge, Malcolm (1972). Chronicles of Wasted Time. Vancouver: Regent College Publishing. p. 489.

- ↑ "Teresa Georgina Mayor". The Peerage.com. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Annan, Noel; Ferguson, James (18 September 2011). "Obituary: Teresa, Lady Rothschild". The Independent. London: INM. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Solomon,, Flora (1984). Baku to Baker Street. London: HarperCollins Publishers Ltd. p. 226.

- ↑ The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography concludes: "The carefree friendships of Rothschild's early Cambridge years that had continued throughout the war cast a shadow over the last decade of his life. The defection of Burgess to Russia and the uncovering of Blunt as a Soviet agent exposed Rothschild to innuendo and vilification in press and parliament. Rather than let his name record of public service speak for themselves, he sought unwisely to clear himself through the testimony of Peter Wright, an investigator employed by MI5 had every reason to know of his innocence. Clandestine association with so volatile a character aroused further suspicions that Rothschild had broken the Official Secrets Act. Only after voluntarily submitting himself to a long interrogation by Scotland Yard did he emerge with honour and patriotism intact."

- ↑ Wright, Peter (1987). Spycatcher. Toronto: Stoddart. p. 347. ISBN 0-7737-2168-1.

- ↑ Reuters (1990-03-22). "Lord Rothschild, 79, a Scientist And Member of Banking Family". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-03-28.

- ↑ "Rothschild Archive Biography".

- ↑ "National Archives: Royal Commission on Gambling (Rothschild Commission)".

- ↑ Rothschild, Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild (1977-01-01). Meditations of a broomstick. London: Collins. ISBN 0002165120.

- ↑ Jon Agar, "Thatcher, scientist." Notes and Records of the Royal Society 65.3 (2011): 215-232.

- ↑ "History of the BBC: Real Lives 1985". BBC.

- ↑ Hussey, Marmaduke (2001). Chance Governs All. Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 9780333902561.

- ↑ "Written Statement rejecting security allegations against Lord Rothschild | Margaret Thatcher Foundation". www.margaretthatcher.org. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ↑ "Official Secrets Act (Prosecution Policy) (Hansard, 6 February 1987)". hansard.millbanksystems.com. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ↑ "All the gifts but contentment". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 2016-01-04.

- ↑ Perry, Roland (1994). The Fifth Man. London: Sedgwick & Jackson. p. 89. ISBN 9780283062162.

- ↑ Ibrahim, Youssef M. (12 July 1996). "Rothschild Bank Confirms Death of Heir, 41, as Suicide". The New York Times. New York, NY: NYTC. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- 1 2 Nicholl, Katie (2 June 2012). "Rothschild heiress's marriage to Goldsmith scion is over... after she falls for a rapper called Jay Electronica". Daily Mail Online. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Lee, Esther; Brown, Brody (12 August 2014). "Nicky Hilton Engaged to James Rothschild: Hotel Heiress to Marry Heir". Us Weekly. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Jonkers, Philip A. E. "Movers and Shakers of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta". moversandshakersofthesmom.blogspot.com. Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Nathaniel Mayer Victor Rothschild, 3rd Baron Rothschild". The Peerage. Retrieved 22 October 2016.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 46444. p. 8. 31 December 1974.

- ↑ The London Gazette: (Supplement) no. 36452. p. 1548. 31 March 1944.

- ↑ "Fellows 1660-2007" (PDF). Royal Society. Retrieved 21 October 2016.

References

- Rose, Kenneth (2003). Elusive Rothschild: The Life of Victor, Third Baron. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81229-7.

- Wilson, Derek (1994). Rothschild: A story of wealth and power. London: Andre Deutsch. ISBN 0 233 98870 X.

- See also the list of references at Rothschild banking family of England

| Peerage of the United Kingdom | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Walter Rothschild |

Baron Rothschild 1937–1990 |

Succeeded by Jacob Rothschild |

| Baronetage of the United Kingdom | ||

| Preceded by Walter Rothschild |

Baronet (of Tring Park) 1937–1990 |

Succeeded by Jacob Rothschild |