Sedenion

In abstract algebra, the sedenions form a 16-dimensional noncommutative and nonassociative algebra over the reals obtained by applying the Cayley–Dickson construction to the octonions. Unlike the octonions, the sedenions are not an alternative algebra. The set of sedenions is denoted by .

The term sedenion is also used for other 16-dimensional algebraic structures, such as a tensor product of two copies of the biquaternions, or the algebra of 4 by 4 matrices over the reals, or that studied by Smith (1995).

Arithmetic

Like octonions, multiplication of sedenions is neither commutative nor associative. But in contrast to the octonions, the sedenions do not even have the property of being alternative. They do, however, have the property of power associativity, which can be stated as that, for any element x of , the power is well defined. They are also flexible.

Every sedenion is a linear combination of the unit sedenions e0, e1, e2, e3, ...,e15, which form a basis of the vector space of sedenions. Every sedenion can be represented in the form

- .

Addition and subtraction are defined by the addition and subtraction of corresponding coefficients and multiplication is distributive over addition.

Like other algebras based on the Cayley–Dickson construction, the sedenions contain the algebra they were constructed from. So, they contain the octonions (e0 to e7 in the table below), and therefore also the quaternions (e0 to e3), complex numbers (e0 and e1) and reals (e0).

The sedenions have a multiplicative identity element e0 and multiplicative inverses but they are not a division algebra because they have zero divisors. This means that two non-zero sedenions can be multiplied to obtain zero: an example is (e3 + e10)×(e6 − e15). All hypercomplex number systems after sedenions that are based on the Cayley–Dickson construction contain zero divisors.

The multiplication table of these unit sedenions follows:

| × | e0 | e1 | e2 | e3 | e4 | e5 | e6 | e7 | e8 | e9 | e10 | e11 | e12 | e13 | e14 | e15 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| e0 | e0 | e1 | e2 | e3 | e4 | e5 | e6 | e7 | e8 | e9 | e10 | e11 | e12 | e13 | e14 | e15 |

| e1 | e1 | −e0 | e3 | −e2 | e5 | −e4 | −e7 | e6 | e9 | −e8 | −e11 | e10 | −e13 | e12 | e15 | −e14 |

| e2 | e2 | −e3 | −e0 | e1 | e6 | e7 | −e4 | −e5 | e10 | e11 | −e8 | −e9 | −e14 | −e15 | e12 | e13 |

| e3 | e3 | e2 | −e1 | −e0 | e7 | −e6 | e5 | −e4 | e11 | −e10 | e9 | −e8 | −e15 | e14 | −e13 | e12 |

| e4 | e4 | −e5 | −e6 | −e7 | −e0 | e1 | e2 | e3 | e12 | e13 | e14 | e15 | −e8 | −e9 | −e10 | −e11 |

| e5 | e5 | e4 | −e7 | e6 | −e1 | −e0 | −e3 | e2 | e13 | −e12 | e15 | −e14 | e9 | −e8 | e11 | −e10 |

| e6 | e6 | e7 | e4 | −e5 | −e2 | e3 | −e0 | −e1 | e14 | −e15 | −e12 | e13 | e10 | −e11 | −e8 | e9 |

| e7 | e7 | −e6 | e5 | e4 | −e3 | −e2 | e1 | −e0 | e15 | e14 | −e13 | −e12 | e11 | e10 | −e9 | −e8 |

| e8 | e8 | −e9 | −e10 | −e11 | −e12 | −e13 | −e14 | −e15 | −e0 | e1 | e2 | e3 | e4 | e5 | e6 | e7 |

| e9 | e9 | e8 | −e11 | e10 | −e13 | e12 | e15 | −e14 | −e1 | −e0 | −e3 | e2 | −e5 | e4 | e7 | −e6 |

| e10 | e10 | e11 | e8 | −e9 | −e14 | −e15 | e12 | e13 | −e2 | e3 | −e0 | −e1 | −e6 | −e7 | e4 | e5 |

| e11 | e11 | −e10 | e9 | e8 | −e15 | e14 | −e13 | e12 | −e3 | −e2 | e1 | −e0 | −e7 | e6 | −e5 | e4 |

| e12 | e12 | e13 | e14 | e15 | e8 | −e9 | −e10 | −e11 | −e4 | e5 | e6 | e7 | −e0 | −e1 | −e2 | −e3 |

| e13 | e13 | −e12 | e15 | −e14 | e9 | e8 | e11 | −e10 | −e5 | −e4 | e7 | −e6 | e1 | −e0 | e3 | −e2 |

| e14 | e14 | −e15 | −e12 | e13 | e10 | −e11 | e8 | e9 | −e6 | −e7 | −e4 | e5 | e2 | −e3 | −e0 | e1 |

| e15 | e15 | e14 | −e13 | −e12 | e11 | e10 | −e9 | e8 | −e7 | e6 | −e5 | −e4 | e3 | e2 | −e1 | −e0 |

From the above table, we can see that:

The 35 triads that make up this specific sedenion multiplication table with the 7 triads of the octonion used in creating the sedenion through the Cayley–Dickson construction shown in bold red:

{{1, 2, 3} , {1, 4, 5} , {1, 7, 6} , {1, 8, 9}, {1, 11, 10}, {1, 13, 12}, {1, 14, 15},

{2, 4, 6} , {2, 5, 7} , {2, 8, 10}, {2, 9, 11}, {2, 14, 12}, {2, 15, 13}, {3, 4, 7} ,

{3, 6, 5} , {3, 8, 11}, {3, 10, 9}, {3, 13, 14}, {3, 15, 12}, {4, 8, 12}, {4, 9, 13},

{4, 10, 14}, {4, 11, 15}, {5, 8, 13}, {5, 10, 15}, {5, 12, 9}, {5, 14, 11}, {6, 8, 14},

{6, 11, 13}, {6, 12, 10}, {6, 15, 9}, {7, 8, 15}, {7, 9, 14}, {7, 12, 11}, {7, 13, 10}}

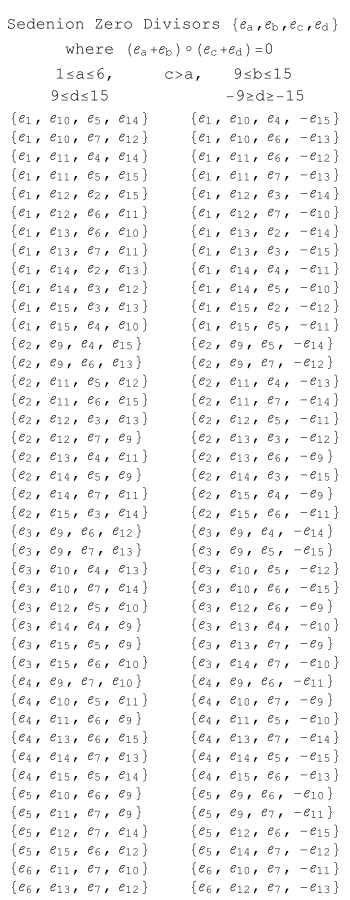

The list of 84 sets of zero divisors {ea, eb, ec, ed}, where (ea + eb)(ec + ed)=0:

Applications

Moreno (1998) showed that the space of pairs of norm-one sedenions that multiply to zero is homeomorphic to the compact form of the exceptional Lie group G2. (Note that in his paper, a "zero divisor" means a pair of elements that multiply to zero.)

See also

Notes

References

- Imaeda, K.; Imaeda, M. (2000), "Sedenions: algebra and analysis", Applied Mathematics and Computation, 115 (2): 77–88, doi:10.1016/S0096-3003(99)00140-X, MR 1786945

- Baez, John C. (2002). "The Octonions". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 39 (2): 145–205. arXiv:math/0105155v4

. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-01-00934-X. MR 1886087.

. doi:10.1090/S0273-0979-01-00934-X. MR 1886087. - Kinyon, M.K.; Phillips, J.D.; Vojtěchovský, P. (2007). "C-loops: Extensions and constructions". Journal of Algebra and its Applications. 6 (1): 1–20. arXiv:math/0412390

. doi:10.1142/S0219498807001990.

. doi:10.1142/S0219498807001990. - Kivunge, Benard M.; Smith, Jonathan D. H (2004). "Subloops of sedenions" (PDF). Comment. Math. Univ. Carolinae. 45 (2): 295–302.

- Moreno, Guillermo (1998), "The zero divisors of the Cayley–Dickson algebras over the real numbers", Sociedad Matemática Mexicana. Boletí n. Tercera Serie, 4 (1): 13–28, arXiv:q-alg/9710013

, MR 1625585

, MR 1625585 - Smith, Jonathan D. H. (1995), "A left loop on the 15-sphere", Journal of Algebra, 176 (1): 128–138, doi:10.1006/jabr.1995.1237, MR 1345298