Political history of the world

| Part of a series on |

| Politics |

|---|

.svg.png) |

|

Academic disciplines |

|

Organs of government |

The political history of the world is the history of the various political entities created by the human race throughout their existence and the way these states define their borders. Throughout history, political entities have expanded from basic systems of self-governance and monarchy to the complex democratic and totalitarian systems that exist today, in parallel, political systems have expanded from vaguely defined frontier-type boundaries, to the national definite boundaries existing today.

Ancient history

In ancient history, civilizations did not have definite boundaries as states have today, and their borders could be more accurately described as frontiers. Early dynastic Sumer, and early dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their borders. Moreover, for the past 200,000 years and up to the twentieth century, many people have lived in non-state societies. These range from relatively egalitarian bands and tribes to complex and highly stratified chiefdoms.

The first states of sorts were those of early dynastic Sumer and early dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively at approximately 3000BCE.[1] Early dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in the north-east of Africa, the kingdom's boundaries being based around the Nile and stretching to areas where oases existed.[2] Early dynastic Sumer was located in southern Mesopotamia with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf to parts of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.[1]

By 2500 BCE the Indus Valley Civilization, located in modern-day Pakistan had formed. The civilization's boundaries extended 600 km inland from the Arabian Sea.[3]

336 BCE saw the rise of Alexander the Great, who forged an empire from various vassal states stretching from modern Greece to the Indian subcontinent, bringing Mediterranean nations into contact with those of central and southern Asia, much as the Persian Empire had before him. The boundaries of this empire extended hundreds of kilometers.[4]

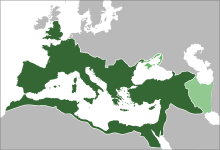

The Roman Empire (27 BCE - 476 CE) was the first western civilization known to accurately define their borders, although these borders could be more accurately described as frontiers;[5] instead of the Empire defining its borders with precision, the borders were allowed to trail off and were, in many cases, part of territory indirectly ruled by others.[6]

Roman and Greek ideals of nationhood can be seen to have strongly influenced Western views on the subject, with the basis of many governmental systems being on authority or ideas borrowed from Rome or the Greek city-states. Notably, the European states of the Dark Ages and Middle Ages gained their authority from the Roman Catholic religion, and modern democracies are based in part on the example of Ancient Athens.

Middle ages

When China entered the Sui Dynasty,[7] the government changed and expanded in its borders as the many separate bureaucracies unified under one banner.[8] This evolved into the Tang Dynasty when Li Yuan took control of China in 626.[9] By now, the Chinese borders had expanded from eastern China, up north into the Tang Empire.[10] The Tang Empire fell apart in 907 and split into ten regional kingdoms and five dynasties with vague borders.[11] Fifty-three years after the separation of the Tang Empire, China entered the Song Dynasty under the rule of Chao K'uang, although the borders of this country expanded, they were never as large as those of the Tang dynasty and were constantly being redefined due to attacks from the neighboring Tartar(Mongol) people known as the Khitan tribes.[12]

After the death of Prophet Muhammad in 632, the Quran and the teachings of Islam inspired the genesis of a new civilization. In less than a century, the Islamic Caliphate rapidly extended its reach from the Atlantic Ocean and Andalusia in the west to Central Asia in the east. The subsequent Muslim empires of the Umayyads, Abbasids, Fatimids, Ghaznavids, Seljuqs, Safavids, Mughals, and Ottomans were among the most influential and distinguished powers in the world during Middle Ages. The period between the 8th and 13th century saw a flourishing of trade, as well as several advances in science, engineering, medecine and mathematics. In Western Europe, briefly mostly united into a single state under Charlemagne around 800CE, a few countries, including England, Scotland, Iceland and Norway, had already effectively become nation states by 1,000CE, with a kingdom (Commonwealth in Iceland's case) largely co-terminus with a people mostly sharing a language and culture.

Over most of the continent, the peoples were emerging around ethnic, linguistic and geographical groups, but this was not reflected in political entities. In particular, France, Italy and Germany, though recognised by other nations as countries where the French, Italians and Germans lived, did not exist as states largely matching the countries for centuries, and struggles to form them, and define their borders, as states were a major cause of wars in Europe until the 20th century. In the course of this process, some countries, such as Poland under the Partitions and France in the High Middle Ages, almost ceased to exist as states for periods. The Low Countries, in the Middle Ages as distinct a country as France, became permanently divided, today into Belgium and the Netherlands. Spain was formed as a nation state by the dynastic union of small Christian kingdoms, augmented by the final campaigns of the Reconquista against Al-Andaluz, the vanished country of Islamic Iberia.

In 1299 CE,[13] the Aztec empire arose in lower Mexico, this empire lasted over 300 years and at their prime, held over 5,000 square kilometers of land.[14][15]

200 years after the Aztec and Toltec empires began, northern and central Asia saw the rise of the Mongol empire. By the late 13th century, the Empire extended across Europe and Asia, briefly creating a state capable of ruling and administrating immensely diverse cultures.[16] In 1299, the Ottomans entered the scene. These Turkish nomads took control of Asia Minor along with much of central Europe over a period of 370 years, providing what may be considered a long-lasting Islamic counterweight to Christendom.[17]

Exploiting opportunities left open by the Mongolian advance and recession as well as the spread of Islam. Russia took control of their homeland around 1613, after many years being dominated by the Tartars (Mongols). After gaining independence, The Russian princes began to expand their borders under the leadership of many tsars.[12] Notably, Catherine the Great seized the vast western part of Ukraine from the Poles, expanding Russia's size massively. Throughout the following centuries, Russia expanded rapidly, coming close to its modern size.[18]

Early modern era

In the 15th and 16th centuries three major Muslim empires formed: the Ottoman Empire in the Middle East, the Balkans and Northern Africa; the Safavid Empire in Greater Iran; and the Mughul Empire in South Asia. These imperial powers were made possible by the discovery and exploitation of gunpowder and more efficient administration. By the end of the 19th century, all three had declined, and by the early 20th century, with the Ottomans' defeat in World War I, the last Muslim empire collapsed.

In 1700, Charles II of Spain died, naming Phillip of Anjou, Louis XIV's grandson, his heir. Charles' decision was not well met by the British, who believed that Louis would use the opportunity to ally France and Spain and attempt to take over Europe. Britain formed the Grand Alliance with Holland, Austria and a majority of the German states and declared war against Spain in 1702. The War of the Spanish Succession lasted 11 years, and ended when the Treaty of Utrecht was signed in 1714.[19]

Less than 50 years later, in 1740, war broke out again, sparked by the invasion of Silesia, part of Austria, by King Frederick II of Prussia. Britain, the Netherlands and Hungary supported Maria Theresa. Over the next eight years, these and other states participated in the War of the Austrian Succession, until a treaty was signed, allowing Prussia to keep Silesia.[20][21] The Seven Years' War began when Theresa dissolved her alliance with Britain and allied with France and Russia. In 1763, Britain won the war, claiming Canada and land east of the Mississippi. Prussia also kept Silesia.[22]

Interest in the geography of the Southern Hemisphere began to increase in the 18th century.[23] In 1642, Dutch navigator Abel Tasman was commissioned to explore the Southern Hemisphere; during his voyages, Tasman discovered the island of Van Diemen's Land, which was later named Tasmania, the Australian coast, and New Zealand in 1644.[24] Captain James Cook was commissioned in 1768 to observe a solar eclipse in Tahiti and sailed into Stingray Harbor on Australia's east coast in 1770, claiming the land for the British Crown.[25] Settlements in Australia began in 1788 when Britain began to utilize the country for the deportation of convicts,[26] with the first free settles arriving in 1793.[27] Likewise New Zealand became a home for hunters seeking whales and seals in the 1790s with later non-commercial settlements by the Scottish in the 1820s and 30s.[28]

In Northern America, revolution was beginning when in 1770, British troops opened fire on a mob pelting them with stones, an event later known as the Boston Massacre.[29] British authorities were unable to determine if this event was a local one, or signs of something bigger[30] until, in 1775, Rebel forces confirmed their intentions by attacking British troops on Bunker Hill.[31] Shortly after, Massachusetts Second Continental Congress representative John Adams and his cousin Samuel Adams were part of a group calling for an American Declaration of Independence. The Congress ended without committing to a Declaration, but prepared for conflict by naming George Washington as the Continental Army Commander.[30] War broke out and lasted until 1783, when Britain signed the Treaty of Paris and recognized America's independence.[32] In 1788, the states ratified the United States Constitution, going from a confederation to a union[30] and in 1789, elected George Washington as the first President of the United States.[33]

By the late 1780s, France was falling into debt, with higher taxes introduced and famines ensuring.[34] As a measure of last resort, King Louis XVI called together the Estates-General in 1788 and reluctantly agreed to turn the Third Estate (which made up all of the non-noble and non-clergy French) it into a National Assembly.[35] This assembly grew very popular in the public eye and on July 14, 1789, following evidence that the King planned to disband the Assembly,[34] an angry mob stormed the Bastille, taking gunpowder and lead shot.[35] Stories of the success of this raid spread all over the country and sparked multiple uprisings in which the lower-classes robbed granaries and manor houses.[34] In August of the same year, members of the National Assembly wrote the revolutionary document Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen which proclaimed freedom of speech, press and religion.[34] By 1792, other European states were attempting to quell the revolution. In the same year Austrian and German armies attempted to march on Paris, but the French repelled them. Building on fears of European invasion, a radical group known as the Jacobins abolished the monarchy and executed King Louis for treason in 1793. In response to this radical uprising, Britain, Spain and the Netherlands join in the fight with the Jacobins until the Reign of Terror was brought to an end in 1794 with the execution of a Jacobin leader, Maximilien Robespierre. A new constitution was adopted in 1795 with some calm returning, although the country was still at war. In 1799, a group of politicians led by Napoleon Bonaparte unseated leaders of the Directory.[35]

Modern era

References

- 1 2 Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. xiii. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- ↑ Daniel, Glyn (2003) [1968]. The First Civilizations: The Archaeology of their Origins. New York: Phoenix Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 1-84212-500-1.

- ↑ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 56. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ de Blois, Lukas; Robartus van der Spek (1997). An Introduction to the Ancient World. New York, US: Routledge. p. 131. ISBN 0-415-12773-4.

- ↑ "A World Defined By Boundaries". Intertext. Syracuse University. 2001. Retrieved 2008-11-21.

- ↑ Kaplan, David H; Jouni Häkli (2002). "The 'Civilisational' Roots of European National Boundaries". Boundaries and Place: European Borderlands in Geographical Context. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 19. ISBN 0-8476-9883-1.

- ↑ Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 118–21. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ Benn, Charles D. (2004). China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. pp. ix. ISBN 0-19-517665-0. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Herrmann, Albert (1970). Historical and Commercial Atlas of China. Ch'eng-wen Publishing House. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ Hucker, Charles O. (1995). China's Imperial Past: An Introduction to Chinese History and Culture. Stanford University Press. p. 147. ISBN 0-8047-2353-2. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- 1 2 Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 134–5. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ Tsouras, Peter (2005). Montezuma: Warlord of the Aztecs. Brassey's. pp. xv. ISBN 1-57488-822-6.

- ↑ Berdan, Frances F.; Richard E. Blanton; Elizabeth H. Boone; Mary G. Hodge; Michael E. Smith; Emily Umberger (1996). Aztec Imperial Strategies. Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 0-88402-211-0.

- ↑ Barlow, R.H. (1949). Extent of the Empire of the Culhua Mexica. Berkeley and Los Angeles Univ. of California.

- ↑ Køppen, Adolph Ludvig; Karl Spruner von Merz (1854). The World in the Middle Ages: An Historical Geography, with Accounts of the Origin and Development, the Institutions and Literature, the Manners and Customs of Three Nations in Europe, Western Asia, and Northern Africa, from the Close of the Fourth to the Middle of the Fifteenth Century. D. Appleton and company. p. 210. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ↑ Jacob, Samuel (1854). History of the Ottoman Empire: Including a Survey of the Greek Empire and the Crusades. R. Griffin. p. 456. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ↑ Thomson, Gladys Scott (2008). Catherine the Great and the Expansion of Russia. Read Books. ISBN 1-4437-2895-0. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

- ↑ Frey, Marsha; Linda Frey (1995). The Treaties of the War of the Spanish Succession (illustrated ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-27884-9. Retrieved 2009-01-29.

- ↑ Dupuy, Richard Ernes; Trevor Nevitt Dupuy (1970). The Encyclopedia of Military History: From 3500 B.C. to the Present. Harper & Row. p. 630. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ Rosner, Lisa; John Theibault (2000). A Short History of Europe, 1600-1815: Search for a Reasonable World (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. p. 292. ISBN 0-7656-0328-4. Retrieved 2009-01-30.

- ↑ Marston, Daniel (2001). The Seven Years' War (illustrated ed.). Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-191-5. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 214. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ Porter, Malcolm; Keith Lye (2007). Australia and the Pacific (illustrated and revised 2007 ed.). Cherrytree Books. p. 20. ISBN 1-84234-460-9. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ Kitson, Arthur (2004). The Life of Captain James Cook. Kessinger Publishing. pp. 84–5. ISBN 1-4191-6947-5. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- ↑ King, Jonathan (1984). The First Settlement: The Convict Village that Founded Australia 1788-90. Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-38080-0.

- ↑ Currer-Briggs, Noel (1982). Worldwide Family History (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 180. ISBN 0-7100-0934-8.

- ↑ Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. p. 216. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ Lancaster, Bruce; John Harold Plumb; Richard M. Ketchum (2001). illustrated, ed. The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 74. ISBN 0-618-12739-9. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 3 Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 218–21. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- ↑ Lancaster, Bruce; John Harold Plumb; Richard M. Ketchum (2001). illustrated, ed. The American Revolution. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. pp. 96–9. ISBN 0-618-12739-9. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ Jedson, Lee (2006). The Treaty of Paris, 1783: A Primary Source Examination of the Treaty That Recognized American Independence (illustrated ed.). The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 37. ISBN 1-4042-0441-5. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ Bloom, Sol; Lars Johnson (2001). The Story of the Constitution (2nd illustrated ed.). Christian Liberty Press. p. 84. ISBN 1-930367-56-2. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- 1 2 3 4 Daniels, Patrica S; Stephen G Hyslop; Douglas Brinkley; Esther Ferington; Lee Hassig; Dale-Marie Herring (2003). Toni Eugene, ed. Almanac of World History. National Geographic Society. pp. 222–25. ISBN 0-7922-5092-3.

- 1 2 3 S. Viault, Birdsall (1990). "The French Revolution". Schaum's Outline of Modern European History (revised ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 180–91. ISBN 0-07-067453-1. Retrieved 2008-01-31.