Non-importation Act

| Origins of the War of 1812 |

|---|

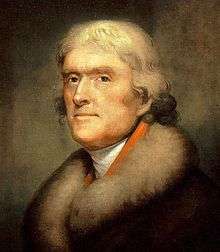

| Thomas Jefferson | |

|---|---|

| |

| 3rd President of the United States | |

|

In office March 4, 1801 – March 4, 1809 | |

| Vice President |

Aaron Burr George Clinton |

| Preceded by | John Adams |

| Succeeded by | James Madison |

The Non-Importation Act was an act passed by the United States Congress on October 28, 1806, which forbade the importation of certain British goods in an attempt to coerce Great Britain to suspend its impressment of American sailors and to respect American sovereignty and neutrality on the high seas. This was the first attempt of President Thomas Jefferson's administration to respond economically, instead of militarily, to the British actions. The act was suspended, but was quickly replaced by the Embargo Act of 1807, which imposed more trade restrictions with Britain, as well as with France. It was one of the acts leading up to the War of 1812.

Background

Due to British and French interference with American shipping during the Napoleonic Wars, American Congressmen called for action.[1] Some favored a total prohibition while other wanted limited action. After much debate, those calling for limited action would eventually prevail.[1]

After three months of debate, the Non-Importation Act of 1806 was passed by Congress and signed by President Jefferson on April 18, 1806. It went into effect on November 15, 1806. It was the first economically based response to Britain's failure to accept American neutrality rights during the Napoleonic Wars. Britain was guilty of impressment on the high seas and even threatened further action against the United States if it did not curtail its alleged neutral trade.[1] The bill was a threat to Britain's economic well-being by attempting to disrupt its flow of commerce. Most importantly, the Non-Importation Act of 1806 would pave the way for future acts of Congress such as Jefferson's Embargo Act of 1807 and the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809. The Non-Importation Act of 1806 would lay the foundations of defining foreign trade and foreign relations for a very important time in United States history.[2]

Banned items

The following items were banned under the Non-Importation Act of 1806:

- All articles of which leather, silk, hemp, flax, tin (except in sheets), or brass was the material of chief value

- All woolen clothes whose invoice prices shall exceed 5/- sterling per square yard

- Woolen hosiery of all kinds

- Window, glass and glassware

- Silver and plated goods

- Paper

- Nails

- Spikes

- Hats

- Ready-made clothing

- Playing cards

- Beer, ale and porter

- Pictures and prints

The penalties for infraction were a loss of the goods as well as a fine of three times their value.[2]

Shortfalls

The act itself had many shortfalls, ultimately leading to it being supplanted by the Embargo Act of 1807. John Randolph, leader of the republican dissidents, described the law as "a milk-and-water bill, a dose of chicken-brother to be taken nine months hence".[1] Enforcement of the act would be delayed from April to November 1806 and the list of banned British goods excluded those most important both to British exporters and American buyers. These items included cheap woolens, coal, iron, steel, and British colonial produce.[1] Such goods were omitted from the ban since these commodities could not be obtained from other foreign sources, nor could they be made in the states.[2] Therefore, the United States attempted to send a message to Great Britain, while at the same time protecting its own economic well-being. The bill was a very mild threat, and the actual hopes were that by delaying its enforcement from April to November, Britain would change its ways and relieve the United States of any discomfort the bans might cause if they actually needed to be enforced.[1]

Enforcement

Great Britain did not mend its ways and the bill began to be strictly enforced. Due to outcry by merchants because of difficulties in enforcement and the strain on profits, the bill was suspended just five weeks after its initial enforcement, until mid-1807. President Jefferson was given the power to suspend it even longer if he thought it to be in the public's best interest.[3] Jefferson suspended it again in March 1807, which allowed the bill to lay dormant for nearly an entire year. Unfortunately, Congress failed to address and amend the shortcomings of the bill that its brief enforcement had uncovered.[4]

Gallatin's contributions

Despite failure to amend the bill, it was put back into effect in order to preserve the honor and independence of the United States.[5] Congress would eventually address some problems with the bill when it asked United States Secretary of the Treasury, Albert Gallatin, what should be done. Gallatin complained that the bill was badly worded as it lacked specificity in certain situations. For instance, many accepted imported items come wrapped in materials like paper, which was forbidden. This led to a discussion of whether the enclosed items would be permitted to enter. Some banned materials, like silver, were used to create permitted goods, like watches. This presented another problem, which Gallatin wanted clarified because, without a revision, he thought the bill would only raise more questions than it answered.[5]

Congress would give a meek response to Gallatin's opinion, despite its public support, mainly because the Embargo Act was being rushed through Congress in a four-day span. The act was being rushed because port customs inspectors were noticing that banned English goods were being obtained from other countries acting like a middleman to circumvent the act. At this time, Gallatin suggested that complete non-intercourse could be administered far more effectively.[6]

Replacement Acts

The Embargo Act of 1807, with its ban of trade between the United States and all foreign ports, would help reshape the United States economy. By closing the economy, the United States was pushed into industrialization because it could no longer import the manufactured goods it needed. Eventually, this act too would be replaced because of a lack of popular support and economic distress. The Non-Intercourse Act of 1809 would supersede the Embargo Act by lifting the embargoes between the United States and all foreign ports, except with the "unrepentant belligerents" of Great Britain and France.[7] Despite this revision, the damage had already been done. The export boom of the time before the act had come to a halt, and although it made a slight comeback after 1809, the War of 1812 stopped all economic progress.[8]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Perkins Bradford. "Jefferson and Madison: The Diplomacy of Fear and Hope." The Creation of a Republican Empire, 1776-1865. Cambridge University Press, 1993. Cambridge Histories Online. Cambridge University Press. 15 March 2010. DOI: 10.1017/CHOL97805213820 90.006

- 1 2 3 Heaton 1941, p. 179

- ↑ Heaton 1941, p. 180

- ↑ Heaton 1941, p. 181

- 1 2 Heaton 1941, p. 182

- ↑ Heaton 1941, p. 188

- ↑ Heaton 1941

- ↑ Mancall, Peter C., Thomas Weiss and Robert Whaples. "United States" The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. Joel Mokyr. Copyright 2003, 2005 by Oxford University Press, Inc. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History: (e-reference edition). Oxford University Press. University of Michigan- Ann Arbor. 15 March 2010.

References

- Embargo Act of 1807 at Bartleby.com

- Heaton, Herbert. "Non-Importation, 1806-1812" The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 1, No. 2 Nov. 1941. Published by: Cambridge University Press of behalf of the Economic History Association. pp. 178–198.