History of the North British Railway (until 1855)

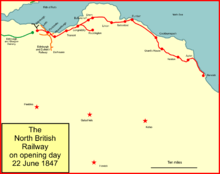

The History of the North British Railway until 1855 traces the founding and construction of the railway company. It built and opened its line between Edinburgh and Berwick (later Berwick on Tweed) and formed part of the first rail link between Edinburgh and London (although with two water breaks). The line opened in 1846.

The first chairman, John Learmonth, wanted to enlarge the geographical area of dominance of the NBR and committed huge sums of money to the process even before opening the first line. Some of the commitments were in vain, but he acquired the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway as a first step to reaching Carlisle, part of the bitter and enduring rivalry with the Caledonian Railway. Making the Hawick line included purchasing the obsolescent Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway and converting it for locomotive operation.

The railway's operations were popular and successful, although early shortcomings in the civil engineering caused temporary difficulties. Branches to Haddington, North Berwick, Dunse (later spelt Duns) and Kelso were opened. Part of the motivation for their building was the exclusion of rival railway companies, and they did not enjoy such great success.

The drain on the Company's financial resources dragged it down in comparison to the rival Caledonian Railway, and shareholder dissent led to the departure of its first Chairman and his successor, and in 1855 Richard Hodgson took over, with the mandate of rescuing the Company.

Early railways

The Lothian and Fife areas of Scotland had been endowed with minerals, especially coal that led to adoption of waggonways as a means of transport in the eighteenth century. These early lines used horse traction and wooden rails, and in nearly all cases were designed to convey coal and limestone over short distances to a harbour for onward transport. In the nineteenth century, the notion of longer distance lines began to take hold, but for the time being available technology prevented that idea becoming a practicable proposition.

In the first years of the nineteenth century, the use of iron rails became commonplace, and it was possible to think in terms of trains, rather than two or three wagons, and primitive locomotives came into use.[1] The so-called coal railways of the Monklands were starting to adopt steam traction, and also to carry passengers in some cases. The Monkland and Kirkintilloch Railway of 1825 and the Garnkirk and Glasgow Railway 1831 were pioneers.

It was the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1825 which indicated that technological progress could make a successful railway over longer distances using locomotive power, and the Liverpool and Manchester Railway of 1830 showed that an inter-city steam railway could be viable. Indeed, the success of the passenger part of the L&MR operation seems to have taken everyone by surprise.[2] When the London and Birmingham Railway opened, followed by the Grand Junction Railway of 1833, connecting Birmingham with the Liverpool and Manchester line, the notion of a railway network began to take hold,[3] and suddenly it seemed as if the whole of Great Britain must be connected into it.[4][5]

Longer distance railways

The first long-distance line in Scotland was the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, opening in 1832, and this too was commercially successful beyond the expectations of its promoters. The E&GR had been built to the track gauge of 4 ft 8½ inches, whereas most of the earlier Scottish lines had been built with a gauge of 4 ft 6in. Although at that time interconnection with English railways was not yet considered, the selection must have been influenced by the perceived technical superiority of the Stockton and Darlington and its imitators.[6]

If English railways seemed to be congregating in the Midlands and North of England, and slowly progressing northwards, then perhaps Scottish railways needed to be promoted to extend southward to join them. As the money market became freer as the 1830s moved on, a number of proposals were put forward for connecting central Scotland with the English network. (In addition, many schemes were promoted for domestic Scottish lines, but the controversy was not so intense for them.)

Suddenly the newspapers were full of commentary about the line to England, with wild schemes being praised by their promoters and condemned by their opponents. For the time being it was assumed that only a single route could be commercially viable to handle all the traffic. It was critical design a route that could cross the high ground of the Southern Uplands and the Cheviot Hills and the Pennines, usable by the technically primitive locomotives of the day, which were unable to ascend steep and lengthy gradients. In 1835 the Grand Junction Railway, already planning to reach Preston and later Carlisle, commissioned the young engineer Joseph Locke to propose routes from Glasgow to Carlisle. His report made the difficulties plain: a west coast route (as the Carlisle options were beginning to be called) had to ascend steep gradients, or go in a wide westerly circuit round them. The Grand Junction investors had other preoccupations further south and the idea was deferred for the time being.

More modest schemes were being proposed, though, and in 1836 plans for a line from Edinburgh to Dunbar by way of Haddington had been prepared. In the same year a line from Edinburgh through Jedburgh and under Carter Fell to Newcastle upon Tyne was put forward, but neither of these schemes was progressed further. However, on 24 October 1838 a Great Northern Junction Railway was proposed by a meeting of promoters; this time the line would run through Berwick. Work was done on route design, by George Stephenson, who found that gradients and engineering works would be much easier than going over the flank of the Southern Uplands. In February 1839 a prospectus was issued; the name had been changed to the Great North British Railway. The capital required for the scheme was £2 million.[7][8]

The Smith-Barlow Commission

The considerable public interest continued, and the Government decided that the matter should be decided in the national interest. In 1840 it appointed a commission to advise it, and Professor Peter Barlow of the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, and Colonel Sir Frederick Smith, Inspector General of Railways at the Board of Trade, were appointed to "make recommendations on the most effective means of railway communication from London to Edinburgh, Glasgow and Dublin". In fact the major part of their consideration was a route from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Carlisle or Newcastle. Both of the English places already had definite schemes in hand to place them on the English network, so the gap lay in southern Scotland, and Dublin was not a central issue.

The Commission considered 16 schemes, although many of them were no more than minor variations of others. In several cases the promoters of schemes were unable to provide more than the most basic details of their proposals and their costs, and the Commissioners found wild and inexplicable variations in unit costs assumed.[8]

Their report was published on 15 March 1841: they repeated the assumption that only one line was required linking Scotland and England. The Annandale route to Carlisle via Beattock was favoured. Although the gradients would be challenging, the route had the advantage of being reasonably direct, and serving both Glasgow and Edinburgh equally well. Importantly, their recommendation was heavily qualified: anyone could build such a line provided they gave an undertaking to reach Lancaster, which at that time was the northern extremity of planned English railways. If this undertaking were not given, an east coast route via Newcastle would have preference. This ambiguity was fatal to the authority of their report.

There were two further fundamental shortcomings in their recommendation: it was not mandatory; and there was no Government money on offer to build the recommended line. Most people had assumed that public money would be made available to build the preferred route; the sudden tightness of the commercial money market ensured that no group of promoters rushed to do the Commission's bidding.

The passage of time had changed attitudes to railway speculation; the success of the first inter-city railways and the further success of local feeders and secondary routes, encouraged the belief that there could be more than one route to England, and in fact that any route could be viable on its own terms. The Commission's findings had become irrelevant.

The North British Railway takes shape

Nonetheless the start of the Commission's work, coupled with an extreme tightness of the money market, had put paid to the immediate prospect of the £2 million Great North British Railway. In January 1842 John Learmonth, chairman of the Edinburgh Committee of the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway, chaired a meeting proposing a more modest scheme from Edinburgh to Dunbar only. They obtained the surveys of the Great North British Railway and intended to follow the same route as far as Dunbar; and they determined to call their line the North British Railway. A prospectus was issued in February 1842; there was to be a branch to Haddington, and the capital was to be £500,000. Haddington, a Royal Burgh and important county market town was displeased to be on a branch line; the earlier proposals had put it on the main line. Learmonth was anxious to keep the capital cost under control, and routing through Haddington would have materially increased capital cost and running cost due to the more difficult terrain. Dunbar too was disappointed to find that its terminus was to be south of the town, and not connecting its important fishing harbour; here the reason was the intended later extension to Berwick: Learmonth had a clear vision that Dunbar was only a short-term terminus; the station needed to enable a later extension.

The track gauge too was now determined not by local whim, but by the imperative of joining up with the English network; the notion of a "standard gauge" of 4 ft 8½ in was taking hold.

There was now a sense of urgency about raising money, for the provisional Caledonian Railway was also planning its future line and trying to raise money. Quite apart from the now discredited idea of only one line being viable, the capital required for a long distance railway was huge, and the gross available capital was not unlimited. Already the rivalry for supremacy between the North British Railway and the Caledonian Railway was in action. In fact both lines found that they could not raise enough money to go to Parliament in the 1843 session as they had hoped.

A revised route with steeper gradients had been considered earlier, in an attempt to reduce construction costs by 8%, and further cost-paring might have been attempted at this stage. Now Learmonth was persuaded by George Hudson, an English railway promoter and financier, to increase interest in his scheme by putting forward a more ambitious scheme, going all the way to Berwick (later known as Berwick-upon-Tweed. At 56 miles, this would increase construction costs to £900,000, but be more attractive to investors: it would link with the proposed Newcastle and Berwick Railway and form part of a future chain of railways reaching London. Hudson agreed to subscribe £50,000, and he did so in due course, although he then passed his holding to the York and North Midland Railway, which he controlled.[9] The railway engineer John Miller was asked to revisit the route surveys to reduce cost, and he did so, getting the cost of construction down to £800,000, though this figure omitted the acquisition of coaching stock.[7] The Edinburgh terminus was altered to be at North Bridge, having previously been intended at Leith Walk.[9]

The Act secured

With the new scheme, the promoters were able to submit a Bill to Parliament in the 1844 session. The most serious potential opponent to the scheme in Parliament was the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway (E&DR) which feared abstraction of its traffic. The E&DR was an obsolescent horse-drawn railway with stone-block sleepered track; its principal traffic was coal but passengers were carried. To eliminate the opposition, the North British promoters agreed to buy that railway for £133,000[note 1] The NBR Chairman John Learmonth already contemplated a long branch from Edinburgh to Carlisle using the E&DR as its northern termination; reaching Carlisle would connect to the West Coast route to London and the industrial north west of England. Moreover, the E&DR had a branch to Leith docks, and important outlet to shipping; securing the E&DR would automatically acquire that connection.

With E&DR opposition neutralised, there was relatively little else in the way, and the North British Railway secured its authorising Act of Parliament on 4 July 1844.[note 2][7][10] The rival Caledonian Railway had not got a far as submitting a Bill in this session.

Construction and preparation

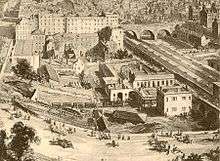

The engineer Miller proceeded with building the main line. He designed the Dunglass Viaduct, near Cockburnspath. It had six arches; the main span was 135 feet, 111 feet high, approached by three and two respectively of 30 feet each.[11] Stations were basic, reflecting the skimping of the budget, and this included the Edinburgh station. The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway was extending its line from Haymarket to a joint Edinburgh station which was to be called "North Bridge". The station was being built by the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway and it was not ready until 3 August 1846.[7][9] The line was laid with 70 lb per yard rails in 12 feet lengths[11]

There was a large depression on a west to east alignment, the Nor' Loch, with Princes Street and the New Town to the north of it, and the Old Town to the south. This had been a disgusting refuse and cess pit, but it was somewhat improved in 1820 when two sets of gardens were made on the area. It was on this land that the North British Railway terminal for Edinburgh was built; the passenger station was immediately east of the North Bridge, and the goods station was squeezed in east of that on the north side of the line.

The Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway had long wished to extend to the city centre from its Haymarket terminal, and the opportunity was now taken to extend to the North Bridge station, running through the western gardens of the Nor' Loch, partly in tunnel, and passing through the northern arch of the North Bridge. The railway was fortunate in being allowed to take this land, and the lines and stations of Edinburgh would be very different today if this had not been permitted by the city authorities. High construction of station buildings was not permitted, and the major disadvantage for arriving passengers was the strenuous climb from platform to street level. The North British booking offices were later provided on Waverley Bridge; the building is still in existence.[12]

The construction of the main line was not without disorder:

Cockburnspath: The continued disturbances among the railway workmen at this station on pay days have induced the authorities to send out a detachment of Dragoons from Jock's Lodge [a cavalry barracks near Edinburgh]. Their arrival on Saturday morning was very anxiously looked for. As it is the intention of Messrs Ross and Mitchell, the contractors, to turn off about 500 of the most refractory, and burn their mud huts, to prevent their locating in the district, a serious disturbance might have been looked for, had the military not been on hand. As it is, we have not heard of any attempt at a row.[13]

Two million tickets were ordered from McDoland and McIver in preparation for the opening; Edmondson's style of pasteboard tickets dated on issue by a press, appear to have been used from the start.[14]

The opening date had been envisaged to be 1 May 1846, but this was overrun, and General Pasley, the Inspecting Officer of the Board of Trade visited for a formal inspection on 15 May 1846. The line was not ready, and he refused the requested permission; even a partial opening from Edinburgh to Cockburnspath was declined. He revisited the line on 16 June, this time finding the works satisfactory.

Opening

General Pasley, the Board of Trade Inspecting Officer reviewed the line on 17 June and passed it, so it was given a ceremonial opening on 18 June 1846, and opened to public passenger trains on 22 June 1846.[9][10][11][14][15]

The Haddington branch was included in the opening.[16] There were five passenger trains each way on the main line, supplemented by ten short workings between Edinburgh and Inveresk. The trains were notable for having better accommodation for third class passengers than was usual on railways at the time. 26 locomotives had been acquired from R and W Hawthorn. Goods trains did not start operation until 3 August 1846.[7] At this stage £1,460,000 had been expended.[9]

The passenger train service was five main line trains daily, with two on Sundays (four weekdays and two on Sundays on the Haddington branch), with an additional ten trains daily between Edinburgh and Musselburgh.[11] Considerable controversy was generated among those shareholders and others who had a religious objection to the running of trains on Sundays. For example, at an ordinary shareholders' meeting on 27 August 1846, "A discussion of nearly three hours' duration next took place in regard to the running of railway trains on the Sabbath. It was brought on by Mr Blackadder, who produced a great number of petitions and remonstrances against the desecration of the Sunday."[17]

Initially there were fifteen stations, taken from public advertisements by the Company:

Edinburgh, Portobello, Musselburgh (later Inveresk), Tranent (later Prestonpans), Longniddry, Ballencrieff, Drem, Linton (later East Linton), Dunbar, Cockburnspath, Grant's House, Reston, Ayton, and Berwick.[9]

There seem to have been several other stations brought into use at a very early date and not necessarily formally announced, and indeed some of the stations were considered provisional "until it was better ascertained from the traffic whether permanent stations should be erected at these places or elsewhere".[14] One new station was at Meadowbank, subsequently known as St Margaret’s. It was used by Queen Victoria in 1850 when returning to the Palace of Holyroodhouse, which was nearby; the station also became known as The Queen's Station. Jock's Lodge station, a quarter mile east of Meadowbank, was opened at an early date, and closed on 1 July 1848.[note 3] A Joppa station is thought to have opened before 1848 also. East Fortune, Beltonford goods station, and Innerwick and Burnmouth all opened between 1848 and 1850.[9]

The definition of a station seems to have been odd: referring to trains to the market at Haddington, a NBR advertisement stated, "On Fridays a Market Train will leave Cockburnspath for Haddington at 10 a.m. returning at 4 p.m., calling at all the intermediate stations and at Innerwick. [emphasis added]".[18]

The Edinburgh station occupied the eastern end of the present-day Waverley station site. On 1 August 1846, the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway opened its extension line from Haymarket.[note 4] For the time being the station facilities consisted of little more than a platform and a booking office (located on Waverley Bridge),[9] and there was no railway connection between the two lines.

Work on providing even a basic station took until 17 May 1847, and from this time the Edinburgh station gradually became known as the "General Station". Both the main line railways used the station but there was still no railway connection between them, and the North British Railway passenger trains used a single temporary platform. The adjoining Canal Street station was also opened on 17 May 1847 when the rope worked line of the Edinburgh, Leith and Granton Railway from Scotland Street was brought into use. A sharp curve connected this line to the Glasgow line. The roof of the new station was limited to 42 feet above the rails because of daylight requirements for neighbours; North Bridge was reconstructed as part of the work.[7][9]

Land acquisition had been very expensive, although this was not declared to shareholders until 8 March 1849: £350,000 had been spent on land, against the £120,000 estimated.[7]

The civil engineering construction was not entirely robust; most of the main line bridges were of timber construction, doubtless part of Miller's process of reducing the capital cost. Even before the line was opened, poor foundations to the central pier of a two span bridge over the Esk near Niddrie Burn caused settlement. Then soon after opening, the Calton Tunnel showed signs of distortion at the eastern portal, and near Portobello a brick skew arch for the Portobello Road and an iron arch and wooden viaduct of eleven spans over the Leith branch of the E&DR line were settling.[9][11]

Further from Edinburgh, the line was breached. Heavy rain in September 1846 put many watercourses into spate, and the runoff exposed some weaknesses in the foundations of some of Miller's bridges: "Stoppage of the North British Railway: Short as the time is since this line was opened to the public, it is now closed. Three of the bridges have been washed away—one at Linton and two others between that place and Dunbar. The cause appears to have been the late heavy rains, and it is thought that the contractors will have to restore the bridges at their own expense. No lives were lost, and passengers are now transmitted by the joint aid of rails and coaches, the latter of which, along with horses, have been forwarded from Edinburgh."[19]

Dalkeith and Hawick

When the 1844 Act was secured, the NBR had agreed to purchase the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway. The chairman of the NBR, John Learmonth, already had a vision of reaching Carlisle over that line, in opposition to the Caledonian Railway, which was planning its line from Glasgow and Edinburgh to Carlisle. (The Caledonian Railway secured its authorising Act on 31 July 1845.)[20] Although the technical condition of the E&DR line was primitive, it connected numerous collieries, and above all it connected to Leith Docks by a branch.[7][21]

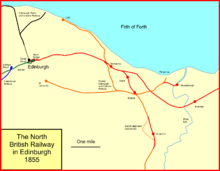

A Bill for a line to Hawick, the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway was entered in the 1845 session; the subscribers at this stage were all directors of the North British Railway. It obtained its Act of Incorporation on 21 July 1845, and at this stage Learmonth made public his intention that the line should proceed to Carlisle, and that the North British Railway should construct it. The shareholders went along with this huge increase in capital, and despite some opposition in Parliament, the Hawick line got its Act on 31 July 1845.[note 5] The North British shareholders voted on 18 August 1845 to raise £400,000 to purchase the nominally independent company, and £160,000 for the Edinburgh and Dalkeith and its conversion and modernisation to a locomotive railway.[7] The NBR took possession of the E&DR on 1 October 1845, payment for the Leith Branch being completed the following December.[14] In acquiring the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway, the North British took over the powers to build from South Esk on the E&DR to Hawick. The NBR also secured powers in 1845 to build from Portobello (on its own future main line) to Niddrie (on the E&DR), the first step in providing the Waverley Route.[9][21]

The Edinburgh and Dalkeith line had to be reconstructed and relaid, in itself a major undertaking for the North British Railway. In addition, a deviation was made where sharp curves existed near Millerhill, and the single track beyond the Dalkeith junction had to be provided; beyond the extremity of the E&DR the River South Esk had to be crossed by a new bridge; the Marquis of Lothian's Waggonway had crossed it, forming an extension of the E&DR, but the old viaduct was inadequate.[22]

The work of improving the E&DR seems to have been done without suspending trains. In 1846 a two-hourly passenger service was more or less maintained over the former E&DR main line until June 1847. Locomotives began working from St Leonards to Niddrie on 15 February 1847, the incline winding engines being taken out of use. Steam hauled services to Dalkeith from St Leonards and from North Bridge station started on 14 July 1847, along with those from General to Gorebridge on the uncompleted Hawick line. St Leonards was closed to passenger traffic on 1 November 1847.[21]

The press had taken an interest in progress:

Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway: This line of railway having recently undergone, to a considerable extent, the necessary alterations for adapting it to locomotive power, an engine was placed on it last week, preliminary to its being employed for the passenger traffic on Monday. On Saturday [30 January 1847], a few of the Directors of the North British Company proceeded to Niddry, in a passenger train drawn by a locomotive, beyond which point the line is not yet ready for steam power. The engine in returning easily ascended the steep inclined plane at the tunnel [approaching St Leonards in Edinburgh], which will thus render the further employment of the stationary engine unnecessary. It is supposed that the remaining portion of the line to Dalkeith will not be ready for two or three months for the employment of steam engines; but the line to Fisherrow being already adapted for this purpose, passengers to that town will in future reap the benefits of this improved means of conveyance.[23]

The operations on this line of railway having been sufficiently advanced to admit of the use of locomotive power for a distance of ten or twelve miles, this powerful agency in working passengers and other traffic was extended on Wednesday to Dalhousie for the first time, a distance of eight miles. The journey is easily accomplished in about half an hour, inclusive of the numerous stoppages at the various villages on the route; and when the sanction of the Board of Trade is obtained, which is expected shortly, the line will be opened to Fushie Bridge, three miles farther south. The branch line to Dalkeith has been abandoned, and passengers for that important town are carried to a point on the line a little southward, and left to find their way thither by walking upwards of a quarter of a mile.[24]

The new construction towards Hawick was completed in stages: a short section from Dalhousie (at the southern end of the E&DR line) to Fushie Bridge (later spelt Fushiebridge) was opened on 14 July 1847; a much longer section from there to Bowland Bridge, a little north of Galashiels, on 4 May 1848; from there to New Town St Boswells (later plain St Boswells)for goods on 8 February 1849 and passengers 20 February 1849; and finally to Hawick on 1 November 1849.[note 6][10][22][25][26]

The new NBR lines and the E&DR lines needed to be connected. Where the NBR main line crossed the E&DR Leith branch, a spur was installed enabling direct running from North Bridge station towards the E&DR Niddry (later spelt Niddrie) direction. In addition a new line was built from Portobello to Niddry; this was to be part of the future main line of the Waverley Route; it had stations at Joppa and Niddry. The Fisherrow branch had been built to get access to the small fishing harbour there, but this was not a great success and the NBR extended that line crossing the River Esk to make a terminus in Musselburgh itself. The "Musselburgh" station on the NBR main line was renamed Inveresk. The line branched from the new Portobello line at Niddry, and the short section of E&DR giving direct running from St Leonards to Fisherrow was removed. These changes were made on 16 July 1847. The Fisherrow stub was reduced to goods status only.[21][26]

This left parts of the E&DR oddly unconnected; both St Leonards and Leith could only be accessed from the Dalkeith direction, and no turnback siding accommodation is evident in period maps. Moreover, the Joppa and Niddry stations were not on the NBR main line. It was not until 1859 (outside the scope of this article) that some of these anomalies were rectified.[note 7][21][27][7][28]

Branches

In the 1846 session even more financial commitment was taken on, as the shareholders agreed on 9 February 1846 to branches to Duns, North Berwick, Tranent and Cockenzie; and from the Hawick line to Kelso, Jedburgh, Selkirk, and Peebles, and extending the Hawick line to Carlisle with a branch to Gretna; the total capital required was £1.68 million. Northward extension was not overlooked, and the proposed Edinburgh and Perth Railway was to be taken over by a share exchange amounting to £800,000. Although the money market was slowing down, North British Railway shares were at a premium (£30 10s per £25 share); the Caledonian Railway was at £10 15s per £50 share.[7]

The numerous NBR branches proposed in 1845 were passed in Parliament on 26 June 1846, but the proposed extension from Hawick to Carlisle was turned down, as was the Edinburgh and Perth Railway. Even so, the financial resources were tight. Receipts from train services for the ten weeks to 31 July were £9,931 (about £50,000 annualised) and the capital of £1.528 million had been expended save for about 4%. Nonetheless Learmonth insisted on resubmitting the Carlisle extension and the Edinburgh and Perth line. £10,000 was spent on a down-payment on the Halbeath Railway, a horse tramway which appeared to be on the future route of the Perth line.[26]

A takeover bid by Hudson

George Hudson had been supportive of the North British in the early months, but now he sponsored reports in the press criticising its engineering quality. There was talk of a new railway from Berwick to Edinburgh via Kelso, cutting out the NBR altogether. The object of this propaganda was clear when Hudson offered to lease the NBR, obviously his objective all along. His terms were to pay 8% on its capital on the main line and 5% on the branches (only Haddington and Hawick—other branch construction was to be deferred) with an option to amalgamate with his York and Newcastle Railway and Newcastle and Berwick Railway. 8% was not a bad offer: "Strange to say, these remarkably liberal terms were rejected by the directors of the North British Company",[29] but John Learmonth had other ambitions for his North British Railway. Scottish pride may also have been a factor in rejecting Hudson's advances.[7][9][11]

"Resolution passed at a Special General Meeting of the North British Railway Company, held at Edinburgh upon the 10th day of February 1847: [it was unanimously] resolved, that the Report now submitted to the Meeting be approved, and that the offer made by the York and Newcastle, and Newcastle and Berwick Railway Companies, for leasing the North British Railway, be rejected."[30] If that announcement was terse, the fact was underlined by exactly as much space being allocated to an announcement immediately below in the Caledonian Mercury. The date of the next shareholders' meeting was advertised, at which Mr Blackadder's motion, "that no Trains shall be run on the Sabbath Day" would be considered. An editorial in the same newspaper supported the decision to reject Hudson's offer.[30]

From this time until early 1848 the price of NBR shares was on a downward slide, and many shareholders regretted the refusal of Hudson's 8% offer; Hudson declined to renew the offer when requested to do so in September 1848. Although part of it had been opened, completion of the Hawick line was stalled through inability to get calls on shares paid.[7]

North Bridge station

On 17 May 1847 the joint station at Waverley Bridge came into use; until then crude platforms without proper facilities had been the sole provision. The Edinburgh and Glasgow and the NBR each used the new station, and the Edinburgh, Leith and Granton Railway opened its Canal Street terminus, alongside but at right angles, facing north. There was a sharp curve connecting that line with the E&GR but the NBR was not connected. The NBR called the station simply "Edinburgh" or "the North Bridge station". The station was still not complete; that was not achieved until 22 February 1848. Even then, the site was very cramped, and relations with the City Council over expansion were difficult. On 5 June 1851 the Royal Assent was finally granted for a modest extension of the station.

Finances

The company had taken on massive capital obligations; as well as the direct cost of its own main line, there was the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway, in all but name a long and expensive branch of the North British Railway; and there was the purchase and conversion of the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway, involving temporary closure of it with corresponding loss of income.

At the September 1847 half yearly shareholders' meeting the Deputy Chairman, Eagle Henderson, was chairing the meeting. He had to excuse the poor results on revenue account due to the "untoward accidents of last year", and "the general depression of trade, the incomplete state of communication between Berwick and Newcastle [while the Tweed and Tyne bridges were being completed] and the serious interruption to the traffic on the Dalkeith branch for several months, while the alterations were being made." Nonetheless a half year dividend of 12s 6d on the £25 ordinary shares [1 per cent annualised] was declared, "looking to ... the certainty of a large increase of traffic for the current half-year".[31] By "the current half year" he meant the future period, so the dividend was paid out of capital.

The company's financial position was no less difficult in 1849; as well as huge capital outlays, it emerged that working expenses had climbed to well over 50% of receipts. As well as taking out a large 4% loan in the personal names of the Directors, the company imposed wage reductions on the staff. This resulted in most of the engine drivers leaving the company, and inexperienced men took over, not without mishap. However, on 29 October 1849 the Hawick branch was completed. This was matched by the completion of the Kelso branch (to a temporary terminus at Wallace Nick) on 7 June 1850.

The general drift continued; in 1852, noting that working expenses were now 56% of receipts, a newspaper recorded:

North British Railway: It appears that the shareholders in this company are becoming uneasy at the state of the property, the greater part of which [the shareholding] is in England... The line was originally intended to connect the southern lines at Berwick with the Scotch lines at Edinburgh. The original act was passed in 1844, and the length of the line then sanctioned was 57 miles, and the amount of the capital authorized was £900,000, being at the rate of £15,500 per mile... [However] the expenditure on capital account in 1851 amounted to £4,275,000... and the average cost per mile [was] £28,690... [The working profit for 1851 after deduction of working expenses] would leave £78,920 to pay interest on loans, preference shares &c, being at the rate of 1.87 per cent. on the total capital expended, notwithstanding the number of years the line has been opened for the development of the traffic, instead of eight per cent. as originally estimated. The directors of the company in the year 1847 refused an offer from Mr. Hudson of eight per cent. per annum for leasing the line to the York, Newcastle and Berwick Company.[32]

A through route to London

When the NBR first opened, passenger services to London were advertised, but these involved change of train, and crossing on foot or by carriage, at the Tweed at Berwick and the Tyne at Newcastle.[note 8] Goods had to be carted through the streets. Both these rivers were to be bridged, but that work would take some considerable time. In both cases temporary wooden structures were used to pass trains before the permanent structure was ready. Temporary bridges passed trains over the Tyne (at Newcastle) from 20 August 1848, and over the Tweed (at Berwick) from 18 October 1848;[note 9] from that date the North British was able to advertise "no change of train".[note 10][7][33][34][35][25]

The rival Caledonian Railway was completed throughout, giving through rail services from both Edinburgh and Glasgow to London, on 1 April 1848; the Caledonian was to be a formidable competitor.[20] Moreover, the North British Railway did not eliminate the coastal steamer route to London: in 1849 the NBR booked 5,792 passengers from Edinburgh to London, while coastal steamers booked 11,584 in the year 1849.[10]

The permanent High Level Bridge at Newcastle was opened on 15 August 1849.[11][33] Although the permanent Tweed bridge had originally been scheduled for completion in July 1849, the permanent bridge was opened to goods traffic on 20 July 1850, and formally opened 29 August 1850.[33][36] A special arrangement was made to pass a special passenger train for visitors to a meeting at Edinburgh for the Royal Society for the Advance of Science on 1 August 1850, only a single line being available.[25]

George Leeman, Chairman of the York Newcastle and Berwick Railway, referred to the special train, and disclosed that the full opening had been intentionally delayed to comply with Royal commitments, in a speech at a dinner in honour of Robert Stephenson in Newcastle on 30 July 1850:

Gentlemen, perhaps you will think I have said enough upon the subject of the High Level Bridge. But, there is another structure, the representation of which adorns this hall, and in regard to which in a very few weeks I hope all the gentlemen I am now addressing will feel a pleasure in being present at the opening. (Applause.) Gentlemen, you are aware that the bridge for the passage of the trains of the Company over [the permanent bridge across] the Tweed has not been opened until the last few days, and then only for one line across the bridge. We have opened the bridge thus far at the present time for the purpose of enabling those travelling to the great meeting of the British Association at Edinburgh to pass over it rather than over the temporary structure that had been used previously. You will ask why we have delayed the laying of the second line and the complete opening of the bridge? We have done so because we considered it an undertaking of such a character that it should receive its finishing stroke from one of the highest in the land. We were anxious to celebrate the opening of the bridge by the presence of one of the most distinguished patrons of science and art in this country, Prince Albert. (Applause.) We have been in communication with his Royal Highness, and we had hoped to have been able to open the bridge at an earlier period than that at which we are now assembled; but, gentlemen, though that has not been done, I am happy to say our hopes in other respects are not only realized, but that they have been exceeded... The announcement I am enabled to make is that not only will his Royal Highness give his own presence on that auspicious occasion, but that her Majesty the Queen will do so likewise.(Loud and continued cheering.)[37]

Fletcher recorded slightly different opening dates:

The first train passed along the temporary bridge used on the erection of the High Level Bridge on the 29th August 1848... The last key on [the permanent structure of] the High Level Bridge was driven by Mr. Hawks on 7th June, 1849; it was opened without any ceremony on August 14th, but it was not brought into ordinary use until the following February [1850]... [There was a formal opening later:] London was connected with Edinburgh through Newcastle and Berwick, when Queen Victoria opened (29th August 1850) the bridges over the Tyne and Tweed, and the Central station, Newcastle.[38]

In opening the Tweed bridge at Berwick, the Queen also named it The Royal Border Bridge.

The completion of the railway routes revived consideration of the onward route to London; the original route had been by way of the York and North Midland Railway and the London and North Western Railway to Euston Square. From October 1852 the possibility of running by a shorter route over the Great Northern Railway to Kings Cross was available, and the North British settled on that; the best time was eleven hours from Edinburgh, an hour quicker than the West Coast route time. Goods traffic, increasingly important, was speeded up too.[7]

The Caledonian Railway was dominant in the emerging railway hub at Carlisle, and as a member of the Euston Confederacy, a cabal of companies allied to the London and North Western Railway, it was becoming a bitter and potent enemy of the North British. However an octuple agreement on traffic to London was concluded on 17 April 1851 for five years, apportioning traffic between the North British, Caledonian Railway, the Lancaster and Carlisle Railway and the London and North Western Railway, the York Newcastle and Berwick Railway, the York and North Midland Railway, the Midland Railway and the Great Northern Railway shared the London - Edinburgh traffic excluding mails and minerals in equal division between the East Coast and West Coast companies on the three Anglo-Scottish routes: Euston - Preston- Carlisle -Edinburgh; Euston - Rugby - York - Edinburgh, and Kings Cross - Doncaster - York - Edinburgh. The NBR formed the northern section of two of these routes and all traffic from places between York and Edinburgh was to be carried by the east coast lines. Receipts from the Berwick - Edinburgh section went to the NBR. The NBR also became a party to the sextuple agreement backdated to 1 January 1851 with the same companies except the Great Northern and York and North Midland companies, allocating shares of all traffic except mails, from Birmingham northwards to Edinburgh with a 50/50 east coast/west coast split on through traffic between these cities. Traffic forwarded from Great Northern station south of York to Edinburgh and Glasgow would be 100% east coast. These arrangements were not unfavourable to the North British, though it still hoped to break the Caledonian monopoly of all traffic through Carlisle, including that to and from Leeds and Bradford, passed to the West Coast via the "Little North Western Railway" between Skipton and Lancaster.[7]

Train service in 1850

The passenger train service in 1850 is shown in Bradshaw for 1850, although at that time the publication was not rigorously complete.

On the main line there were five trains weekdays from Edinburgh "North Bridge" to Berwick, with an additional Edinburgh to Haddington train. The best main line train called intermediately only at Dunbar, leaving Edinburgh at 9:45 am and arriving at Berwick at 11:15 am, offering arrival in London Euston Square at 10:30 pm. The train "carries second class passengers between Edinburgh and Newcastle and the servants of first class passengers throughout." There was a corresponding service northbound. The Haddington branch had four or five trains to and from Longniddry. The Sunday service was two stopping and one (up) or two (down) fast trains. The Dunse (later "Duns") branch had three trains each way connecting with main line trains at Reston, and the North Berwick had three each way connecting at Drem. There was a Wednesday market train on the Dunse branch. There is no mention in Bradshaw of the frequent short trains to Musselburgh (main line) that were laid on at the beginning of the service.

The Dalkeith and Hawick line had six trains weekdays only between Edinburgh and Dalkeith, and three stopping trains each way Edinburgh to Hawick.[39]

Learmonth ousted

Since the beginning, the North British directors had taken on huge financial commitments, and in many cases Directors had taken on individual share allocations on behalf of the Company, and these looked shady to some shareholders. There had been a race to capture territory by sponsoring, directly or indirectly, associated lines and branches. (By contrast, the Caledonian Railway, though equally voracious, had concluded leases of associated lines, which achieved the commitment without requiring the front-end cash outlay.) This issue had attracted increasing criticism from shareholders, and on 18 March 1852 it had to be made clear that there would be no dividend distribution to ordinary shareholders for the half year. A preference share issue, necessary to finance capital commitments, flopped, and a full-blown financial crisis was in progress.

A group of influential English shareholders had submitted a circular demanding a change of directors, and the Chairman, John Learmonth and his deputy said they would be pleased to be relieved of the work of running the company.[40] Three directors announced that they were resigning, and Learmonth said that he would retire in due course. He hoped to do so at a time of his own choosing, but on 13 May 1852 he and two more directors left. Learmonth's deputy, James Balfour, took over as Chairman.[7][41]

Balfour was not the man to lead a great public undertaking like the North British, and was seen infrequently and had little influence. In 1855 he resigned (by wire from Madeira):[7] the announcement in the press was typically low-key:

North British Railway: Mr. John Bain of Morriston has been appointed a director of this line, in room of Mr James Balfour of Whittingham, resigned.[42]

The Chairmanship passed to a better man: Richard Hodgson.[7]

Branch openings

In the 1846 Parliamentary session, the North British Railway had achieved authorisation for a considerable number of branch lines, in addition to the connections to the Edinburgh and Dalkeith line authorised in the previous session.

The branch line to Dunse (later called Duns) from Reston opened on 13 August 1849 (formal) and fully on 15 August 1849.[43]

The short branch at Prestonpans to Tranent, serving colliery workings there, opened on 11 December 1849.[7][10]

The branch line to Kelso from St Boswells opened on 17 June 1850 to a temporary station near Kelso; obstruction from the Duke of Roxburghe frustrated efforts to get a proper Kelso station at once, and the later permanent station was inconveniently located south of the Tweed. The Newcastle and Berwick Railway had earlier promoted a branch to Kelso from Tweedmouth, near Berwick, and Learmonth had envisaged these lines as together forming a strategic east-west link. Relations between the NBR and the North Eastern Railway, successor to the Newcastle and Berwick Railway, were cool and the development never took place.[44]

A number of other railways were promoted in the area the North British considered its own, but the difficult financial position of the NBR meant that they had to raise the capital themselves.

The Peebles Railway was incorporated on 8 July 1853 and opened on 4 July 1855. It ran to Peebles from a junction off the Hawick line at Hardengreen. It worked its own trains, although it joined the North British family from 1858.[7]

The Port Carlisle Dock and Railway Company was incorporated on 4 August 1853, to build a line to Port Carlisle, enabling goods to be brought to Carlisle by-passing the silted up channel of the Solway Firth. This turned out to be an unprofitable business, but it played a part later in getting access to Carlisle for the North British Railway. For now it opened in 1854; its later destiny was not to become obvious for some years. For the time being, it had no connection to the North British Railway.[7][45]

The Border Counties Railway was authorised on 1 July 1854 to build a line through very thinly populated terrain, with suspected, but unproven, coal reserves. It was to connect Hexham on the Newcastle and Carlisle Railway to Bellingham, but later extensions took the line to Riccarton Junction. It too had no connection with the North British Railway until later.[46]

Topography

Hamilton Ellis described the route from a train running point of view (condensed here):

The exit from Edinburgh was through Calton Tunnel followed by about a mile at 1 in 78 falling, but elsewhere most of it rose and fell at 1 in 300, with a mile at 1 in 250 between East Fortune and East Linton. From Innerwick the route became more formidable, rising for about 6 miles to Penmanshiel Tunnel, the first 2¾ miles at 1 in 210 and the rest at 1 in 96, a challenging road for the motive power of those days. The remaining 17½ miles from the summit to Berwick had a fall on a more gentle gradient, mostly 1 in 200 to a level between Reston and Ayton, whence there was a gentle hump before the final descent at 1 in 190 to the short Berwick level.[11]

Hamilton Ellis also described the Berwick station:

The origin of the Berwick station was quaint. On the site was an old border castle built by David I, so that he could watch the English. The North British company thoughtfully demolished this, but kept the building material in order to erect out of it a massive station house with battlements and crenellations, an octagonal tower on one side, and a round tower with a superimposed turret on the other. It lasted until 1926.[11]

Early stations

An exact record of passenger stations open at any time does not appear in official timetables of the day nor in independent publications.

Stations open at the beginning are show in bold. Events after 1859 are not listed.

Main line:

- Edinburgh; also known as Edinburgh North Bridge, Edinburgh General, Edinburgh Waverley Bridge, and (much later) Edinburgh Waverley; the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway line from Haymarket was opened 1 August 1846; the two companies ran their portion of the station separately;

- Meadowbank; also known as St Margaret’s; opened 1850, and after use by Queen Victoria the station was also known as The Queen's station;

- Jock's Lodge; opened by 1 September 1847; closed after May 1848;

- Portobello; (there was a Portobello station on the Edinburgh and Dalkeith Railway Leith branch also);

- Joppa; opened 14 July 1847; on branch to Niddry (Niddrie) and served by Musselburgh branch trains only; resited when Musselburgh branch diverted 16 May 1859;

- Musselburgh; renamed Inveresk 1847; later Inveresk Junction;

- Tranent; renamed Prestonpans 1858;

- Longniddry;

- Ballencrieff; closed 1 November 1847; (the settlement name was spelt Ballancrieff on contemporary maps);

- Drem;

- East Fortune; opened July 1848; (the settlement name was spelt East Forton on contemporary maps);

- Linton;

- Beltonford; this was a goods station, but there was a Friday market train to Haddington from Cockburnspath which picked up passengers here;

- Dunbar;

- Innerwick; opened July 1848;

- Cockburnspath;

- Grant's House; later Grantshouse;

- Reston;

- Ayton;

- Burnmouth; opened July 1848;

- Berwick.[7][25][26]

Edinburgh and Hawick line (after upgrade of the Edinburgh and Dalkeith main line):

- Joppa;

- Niddry; soon usually spelt Niddrie;

- Miller Hill; soon usually spelt Millerhill;

- Gallowshall; opened July 1849; renamed Eskbank in 1850;

- Dalhousie; (named South Esk when first opened by E&DR); NB north of Newbattle Viaduct;

- Gorebridge;

- Fushie Bridge; soon spelt Fushiebridge;

- Tynehead;

- Heriot;

- Burn House; renamed Fountainhall in 1849;

- Stow;

- Bowland;

- Galashiels;

- Melrose;

- Newstead;

- New Town St Boswells; soon renamed St Boswells;

- New Belses; renamed Belses in 1862;

- Hassendean; opened March 1850;

- Hawick.[25]

Richard Hodgson as chairman

With the departure of John Balfour, the North British Railway was at a low point, and needed a dynamic and skilful chairman to build it up. Learmonth's objectives of extending from Hawick to Carlisle, (a distance of 43 miles,) and establishing a network morth of the Forth, were in abeyance. At the end of 1855 the Company appointed Richard Hodgson as their Chairman. Taking over at a most difficult time, he was a leader as determined and ruthless as Learmonth, and equally determined to broaden the scope of the North British Railway, and to fight the Caledonian Railway wherever it was necessary.

Notes

- ↑ The figure is quoted as £113,000 in Dow page 8, and Mullay page 16.

- ↑ Dow says 19 July on page 8

- ↑ The station was at the site of Restalrig Road bridge. There was a cavalry barracks there, and the name Jock's Lodge was simply a district on the outskirts of Edinburgh at the time.

- ↑ Dow and Paterson; Ross says 3 August for goods only.

- ↑ The date of passing of the Edinburgh and Hawick Railway Act. The NBR had pre-emptively acquired the transfer of those powers, and directly acquired the E&DR, by the North British Railway (Edinburgh and Dalkeith Purchase) Act of 21 July 1845. The Act also authorised the connection between the NBR and the E&DR line at Niddrie.

- ↑ Perkins and Macintosh give slightly different dates.

- ↑ Smith and Anderson say that "in 1847 a short spur above the Friggate Burn was authorised so that South Leith [that is, Leith E&DR] passenger trains could run into a separate platform at the new Portobello main line station, thus affording more direct connections with Edinburgh. This opened in summer 1849 and the former E&DR Portobello station nearby closed along with the original route to Niddrie." These events took place in 1859, not 1849, and the reference in Smith and Anderson seems to be a typographical error.

- ↑ Until 1 July 1847 when the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway was completed as far as Tweedmouth, this involved a considerable road journey.

- ↑ Hamilton Ellis says that on 2 September 1848 a carriage was pushed manually to centre of the bridge on the temporary trestle staging.

- ↑ Ross says (page 238) Tweed opened for goods 10 October 1848, passengers 15 October 1848; Hamilton Ellis agrees; Lewin (Aftermath, page 513) says Tyne crossing 29 August 1848 and Tweed 10 October 1848. Hoole says (page 204) Tyne crossing 29 August 1848; Quick agrees 10 October 1848 for Tweed.

References

- ↑ Dow, Andrew (2014). The Railway: British Track Since 1804. Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books Limited. ISBN 978-1-47382-257-3.

- ↑ Donaghy, Thomas J. (1972). Liverpool and Manchester Railway Operations: 1831 - 1845. Newton Abbot: David and Charles (Holdings) Limited. pp. 70–103. ISBN 0-7153-5705-0.

- ↑ Webster, Norman W. (1972). Britain's First Trunk Line: The Grand Junction Railway. Bath: Adams and Dart. pp. 133 onwards. ISBN 0-239-00105-2.

- ↑ Warren, J.G.H. (1970) [1923]. A Century of Locomotive Building by Robert Stephenson and Co (reprint ed.). Newton Abbot: David & Charles Publishers. pp. 175 onwards. ISBN 0-7153-4378-5.

- ↑ Lewin, H.G. (1998) [1925]. The Railway Revolution: Volume 1: Early British Railways (reprint ed.). London: Routledge / Thommes Press. ISBN 0-415-15088-4.

- ↑ Robertson 1983, pp. 126-126.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Ross, David (2014). The North British Railway: A History. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1-84033-647-4.

- 1 2 Robertson, C.J.A. (1983). The Origins of the Scottish Railway System, 1722 - 1844. Edinburgh: John Donald Publishers Ltd. ISBN 0-85976-088X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Dow, George (1946). The First Railway Across the Border. London and North Eastern Railway.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thomas, John (1984). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 6, Scotland, the Lowlands and the Borders. revised by J.S. Paterson. Newton Abbot: David and Charles. ISBN 0-946537-12-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ellis, C. Hamilton (1955). The North British Railway. London: Ian Allan Limited.

- ↑ Meighan, Michael (2014). Edinburgh Waverley Station Through Time. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-445-622-163.

- ↑ Northern Warder and General Advertiser for the Counties of Fife, Perth and Forfar. 21 August 1845. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 Mullay, A.J. (1990). Rails Across the Border. Wellingborough: Patrick Stephens Publishing. ISBN 1-85260-186-8.

- ↑ Lewin 1998, p. 244, amended by Greville, M.D. (January 1956). Journal of the Railway and Canal Historical Society. 2 (1). Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hajducki, Andrew M. (1994). The Haddington, Macmerry and Gifford Branch Lines. Oxford: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-456-3.

- ↑ York Herald. 5 September 1846. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Edinburgh Evening Post and Scottish Standard. 1 August 1846. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ York Herald. 3 October 1846. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 Ross, David (2014). The Caledonian: Scotland's Imperial Railway: A History. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing Limited. ISBN 978-1840-335842.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Smith, W.A.C.; Anderson, Paul (1995). An Illustrated History of Edinburgh's Railways. Caernarfon: Irwell Press. ISBN 1-871608-59-7.

- 1 2 Perkins, Roy; Macintosh, Iain (2012). The Waverley Route Through Time. Stroud: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445609607.

- ↑ Dundee, Perth, and Cupar Advertiser. 5 February 1847. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Kelso Chronicle. 2 July 1847. Missing or empty

|title=(help) reprinted from the Scotsman - 1 2 3 4 5 Quick, M.E. (2002). Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology. The Railway and Canal Historical Society.

- 1 2 3 4 Thomas, John (1969). The North British Railway, volume 1. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4697-0.

- ↑ Ordnance Survey of Great Britain, Six inches to one mile plans, Edinburghshire, published 1853 (surveyed 1852)

- ↑ Cobb, Col M.H. (2003). The Railways of Great Britain—A Historical Atlas. Shepperton: Ian Allan Publishing Limited. ISBN 07110-3003-0.

- ↑ Tomlinson, page 482

- 1 2 Caledonian Mercury. 11 February 1847. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Perthshire Advertiser. 16 September 1847. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Newcastle Journal. 10 January 1852. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 Thomas, volume 1, page 48

- ↑ Lewin, Henry Grote (1968). The Railway Mania and its aftermath (reprint ed.). Newton Abbot: David and Charles (Holdings) Ltd. ISBN 0-7153-4262-2.

- ↑ Hoole, K. (1965). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 4: The North East. Dawlish: David and Charles.

- ↑ The Architect. 7 September 1850. Missing or empty

|title=(help) quoted in Tomlinson, page 507 - ↑ Newcastle Journal. 3 August 1850. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ James Richard Fletcher, The Development of the Railway System in Northumberland and Durham, Address to the Newcastle upon Tyne Association of Students of the Institution of Civil Engineers, 7 November 1901

- ↑ Bradshaw's Rail Times for Great Britain and Ireland, March 1850 (reprint ed.). Midhurst: Middleton Press. 2012. ISBN 978-1-908174-13-0.

- ↑ Edinburgh Evening Courant. 20 March 1852. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Edinburgh Evening Courant. 15 May 1852. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Dundee Courier. 24 October 1855. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Darsley, Roger; Lovett, Dennis (2013). St Boswells to Berwick via Duns: The Berwickshire Railway. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-1-908174-44-4.

- ↑ Darsley, Roger; Lovett, Dennis (2015). Berwick to St Boswells via Kelso including the Jedburgh Branch. Midhurst: Middleton Press. ISBN 978-1-908174-75-8.

- ↑ White, Stephen (1984). Solway Steam: The Story of the Silloth and Port Carlisle Railways 1854 – 1964. Carlisle: Carel Press. ISBN 0-950-9096-1-0.

- ↑ Sewell, G.W.M. (1991). The North British Railway in Northumberland. Braunton: Merlin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-86303-613-9.