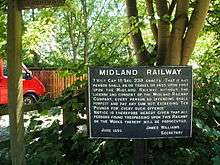

Midland Railway

|

Midland Railway coat of arms at Derby Station. The wyvern that surmounts it had been used by the Leicester and Swannington Railway. It was the emblem of the rulers of Mercia and was used extensively as an emblem by the Midland. | |

| Dates of operation | 1846–1922 |

|---|---|

| Successor | London, Midland and Scottish Railway |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

The Midland Railway (MR) was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1844[1] to 1922, when it became part of the London, Midland and Scottish Railway.[2] It had a large network of lines managed from its headquarters in Derby. It became the third-largest railway undertaking in the British Isles (after the Great Western Railway and the London and North Western Railway).[3]

Origin

The Midland Railway Consolidation Act was passed in 1844 authorising the merger of the Midland Counties Railway, the North Midland Railway, and the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway. These met at the Tri-Junct station at Derby, where the MR established its locomotive and later its carriage and wagon works.

Leading it were George Hudson from the North Midland, dynamic but unscrupulous, and John Ellis from the Midland Counties, a careful businessman of impeccable integrity. James Allport from the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway found a place elsewhere in Hudson's empire with the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway, though he later returned.[4]

The MR was in a commanding position having its Derby headquarters at the junctions of the two main routes from London to Scotland, by its connections to the London and Birmingham Railway in the south, and from York via the York and North Midland Railway in the north.

Consolidation

Almost immediately it took over the Sheffield and Rotherham Railway and the Erewash Valley Line in 1845, the latter giving access to the Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire coalfields. It absorbed the Mansfield and Pinxton Railway in 1847, building the Erewash Valley Line from the latter between Chesterfield and Trent Junction at Long Eaton, completed to Chesterfield in 1862, giving access to the coalfields that became its major source of income. Passengers from Sheffield continued to use Rotherham Masborough until a direct route was completed in 1870.

Meanwhile, it extended its influence in the Leicestershire coalfields, by buying the Leicester and Swannington Railway in 1846,[5] and extending it to Burton in 1849.

The South-West

After the merger, London trains were carried on the shorter Midland Counties route. The former Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway was left with the traffic to Birmingham and Bristol, an important seaport. The original 1839 line from Derby had run to Hampton-in-Arden: the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway had built a terminus at Lawley Street in 1842, and on 1 May 1851 the MR started to run into Curzon Street.[6]

The line south was the Birmingham and Bristol Railway, which reached Curzon Street via Camp Hill. These two lines had been formed by the merger of the standard gauge Birmingham and Gloucester Railway and the broad gauge Bristol and Gloucester Railway.

They met at Gloucester via a short loop of the Cheltenham and Great Western Union Railway. The change of gauge at Gloucester meant that everything had to be transferred between trains, creating chaos, and the C&GWU was owned by the Great Western Railway, which wished to extend its network by taking over the Bristol to Birmingham route. While the two parties were bickering over the price, the MR's John Ellis overheard two directors of the Birmingham and Bristol Railway on a London train discussing the business, and pledged that the MR would match anything the Great Western would offer.[7]

Since it would have brought broad gauge into Curzon Street with the possibility of extending it to the Mersey, it was something that the other standard gauge lines wished to avoid, and they pledged to assist the MR with any losses it might incur.[7] In the event all that was necessary was for the later LNWR to share Birmingham New Street with the Midland when it was opened in 1854, and Lawley Street became a goods depot.[8]

Eastern competition

The MR controlled all the traffic to the North East and Scotland from London. The LNWR was progressing slowly through the Lake District, and there was pressure for a direct line from London to York. Permission had been gained for the Northern and Eastern Railway to run through Peterborough and Lincoln but it had barely reached Cambridge.

Two obvious extensions of the Midland Counties line were from Nottingham to Lincoln and from Leicester to Peterborough. They had not been proceeded with, but Hudson saw that they would make ideal "stoppers": if the cities concerned were provided with a rail service, it would make it more difficult to justify another line. They were approved while the bill for the direct line was still before Parliament, forming the present day Lincoln Branch and the Syston to Peterborough Line.

The Leeds and Bradford Railway had been approved in 1844. By 1850 it was losing money but a number of railways offered to buy it. Hudson made an offer more or less on his own account and the line gave the MR an exit to the north, which became the start of the Settle and Carlisle line, and it gave the MR a much more convenient station at Leeds Wellington.

Hudson's defection

In spite of the objections of Hudson, for the MR and others, the "London and York Railway" (later the Great Northern Railway) led by Edmund Denison persisted, and the bill passed through Parliament in 1846.[9]

Hudson changed his allegiance and promoted a short line to connect his York and North Midland Railway to Knottingley, ostensibly as a quarry line, that would give the Great Northern an easy entry into York.

After Hudson's departure, the MR was in financial difficulties. Opposition to the Great Northern bill had cost a fortune, a great deal of maintenance was overdue, and the Lincoln and Peterborough lines were still to be paid for. Added to this, the Great Northern was taking much of the traffic from the North East, particularly as the MR was dependent on the LNWR from Rugby into London.

The Battle of Nottingham

In 1851 the Ambergate, Nottingham, Boston and Eastern Junction Railway completed its line from Grantham as far as Colwick, from where a branch led to the MR Nottingham station. The Great Northern Railway by then passed through Grantham and both railway companies paid court to the fledgling line. Meanwhile, Nottingham had woken up to its branch line status and was keen to expand. The MR made a takeover offer only to discover that a shareholder of the GN had already gathered a quantity of Ambergate shares. An attempt to amalgamate the line with the GN was foiled by Ellis, who managed to obtain an Order in Chancery preventing the GN from running into Nottingham. However, in 1851 it opened a new service to the north that included Nottingham.[10]

In 1852 an ANB&EJR train arrived in Nottingham with a GN locomotive at its head. When it uncoupled and went to run round the train, it found its way blocked by a MR engine while another blocked its retreat.[11] The engine was shepherded to a nearby shed and the tracks were lifted. This episode became known as the "Battle of Nottingham" and, with the action moved to the courtroom, it was seven months before the locomotive was released.

The Euston Square Confederacy

The London and Birmingham Railway and its successor the London and North Western Railway had been under pressure from two directions. Firstly the Great Western Railway had been foiled in its attempt to enter Birmingham by the Midland, but it still had designs on Manchester. At the same time the LNWR was under threat from the GN's attempts to enter Manchester by the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway.

The LNWR was led by the brilliant but totally unscrupulous Captain Mark Huish. At first, observing the poor state of the MR finances, he had proposed an amalgamation that Ellis opposed, seeking better terms. He then formed an alliance with the MS&LR and the MR against the GN, which became known as the Euston Square Confederacy.

To London

King's Cross 1857 – 1868

In 1850 the MR, though much more secure, was still a provincial line. Ellis realised that if it were to fend off its competitors it must expand outwards. The first step, in 1853, was to appoint James Allport as General Manager and the next was to shake off the dependence on the LNWR to London.

Although a bill for a line from Hitchin into King's Cross jointly with the GN, was passed in 1847 it had not been proceeded with.

The bill was resubmitted in 1853 with the support of the people of Bedford, whose branch to the LNWR was slow and unreliable, and with the knowledge of the Northamptonshire iron deposits.

The Leicester and Hitchin Railway ran from Wigston to Market Harborough, through Desborough, Kettering, Wellingborough and Bedford, then on the Bedford to Hitchin Line, joining the GN at Hitchin for King's Cross. The line began its life in a proposition presented for the shareholders by George Hudson on 2 May 1842 as: "To vest £600,000 in the South Midland Railway Company in their line from Wigston to Hitchin." a full decade before realisation. The delay was partly due to the withdrawal of GN's interest in the competing scheme, the Bedford and Leicester Railway, after Midland purchased the Leicester and Swannington Railway and the Ashby Canal and Tramway,[12] which were to have been the feeder lines. With the competition thwarted there was less rush to have this line as well as its branch lines to Huntingdon (from Kettering) and Northampton (from Bedford) finished. Both these branches were subsequently built by independent companies.

While this took some of the pressure off the route through Rugby, the GNR insisted that passengers for London alight at Hitchin, buying tickets in the short time available, to catch a GNR train to finish their journey. James Allport arranged a seven-year deal with the GN to run into King's Cross for a guaranteed £20,000 a year (equivalent to £1,720,000 in 2015),[13]. Through services to London were introduced in February 1858.[14] The construction of the Leicester and Hitchen railway cost £1,750,000[1] (equivalent to £158,830,000 in 2015).[13]

St. Pancras 1868

By 1860 the MR was in a much better position and was able to approach new ventures aggressively. Its carriage of coal and iron – and beer from Burton-on-Trent – had increased by three times and passenger numbers were rising, as they were on the GN. Since GN trains took precedence on its own lines, MR passengers were becoming more and more delayed. Finally in 1862 the decision was taken for the MR to have its own terminus in the Capital, as befitted a national railway.

On 22 June 1863, the Midland Railway (Extension to London) Bill was passed:

- "An Act for the Construction by the Midland Railway Company of a new Line of Railway between London and Bedford, with Branches therefrom; and for other Purpose".[15]

The new line deviated at Bedford, through a gap in the Chiltern Hills at Luton, reaching London by curving around Hampstead Heath to a point between King's Cross and Euston.

St Pancras station, completed in 1868, is a marvel of Gothic Revival architecture, in the form of the Midland Grand Hotel by Gilbert Scott, which faces Euston Road, and the wrought-iron train shed designed by William Barlow. Its construction was not simple, since it had to approach through the ancient St Pancras Old Church graveyard. Below was the Fleet Sewer, while a branch from the main line ran underground with a steep gradient beneath the station to join the Metropolitan Railway, which ran parallel to what is now Euston Road.[16]

The construction of the London Extension railway cost £9,000,000[1] (equivalent to £730,290,000 in 2015).[13]

To Manchester

From the 1820s proposals for lines from London and the East Midlands had been proposed, and they had considered using the Cromford and High Peak Railway to reach Manchester (See Derby station).

Finally the MR joined with the Manchester and Birmingham Railway (M&BR), which was also looking for a route to London from Manchester, in a proposal for a line from Ambergate. The Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midlands Junction Railway, it received the Royal Assent in 1846, in spite of opposition from the Sheffield, Ashton-Under-Lyne and Manchester Railway. It was completed as far as Rowsley a few miles north of Matlock in 1849. However the M&BR had become part of the LNWR in 1846, thus instead of being a partner it had an interest in thwarting the Midland.

In 1863 the MR reached Buxton, just as the LNWR arrived from the other direction by the Stockport, Disley and Whaley Bridge Railway. In 1867 the MR began an alternative line through Wirksworth (now the Ecclesbourne Valley Railway), to avoid the problem of the Ambergate line. The section from Wirksworth to Rowsley, which would have involved some tricky engineering, was not completed because the MR gained control of the original line in 1871, but access to Manchester was still blocked at Buxton. At length an agreement was made with the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway (MS&LR) to share lines from a branch at Millers Dale and running almost alongside the LNWR, in what became known as the Sheffield and Midland Railway Companies' Committee.

Continuing friction with the LNWR caused the MR to join the MS&LR and the GN in the Cheshire Lines Committee, which also gave scope for wider expansion into Lancashire and Cheshire, and finally a new station at Manchester Central.[17]

In the meantime Sheffield had at last gained a main-line station. Following representations by the council in 1867 the MR promised to build a through line within two years. To the MR's surprise, the Sheffield councillors then backed an improbable speculation called the Sheffield, Chesterfield, Bakewell, Ashbourne, Stafford and Uttoxeter Railway. This was unsurprisingly rejected by Parliament and the Midland built its "New Road" into a station at Pond Street.

Among the last of the major lines built by the MR was a connection between Sheffield and Manchester, by a branch at Dore to Chinley, opened in 1894 through the Totley and Cowburn Tunnels, now the Hope Valley Line.

To Scotland

In the 1870s a dispute with the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) over access rights to the LNWR line to Scotland caused the MR to construct the Settle and Carlisle line,[18] the highest main line in England, to secure access to Scotland.

The dispute with the LNWR was settled before the Settle and Carlisle was built, but Parliament refused to allow the MR to withdraw from the project. The MR was also under pressure from Scottish railway companies, which were eagerly awaiting the Midland traffic reaching Carlisle as it would allow them to challenge the Caledonian Railway's dominance on the West Coast traffic to Glasgow and Edinburgh. The Glasgow and South Western Railway had its own route from Carlisle to Glasgow via Dumfries and Kilmarnock, whilst the North British Railway had built the Waverley Line through the Scottish Borders from Carlisle to Edinburgh. The MR was obliged to go ahead and the Settle to Carlisle opened in 1876.[18]

Later history

The Nottingham and Melton Line of the Midland Railway opened to passenger traffic in 1880.[19]

By the middle of the decade investment had been paid for; passenger travel was increasing, with new comfortable trains; and the mainstay of the line – goods, particularly minerals – was increasing dramatically.

Allport retired in 1880, to be succeeded by John Noble and then by George Turner. By the new century the quantity of goods, particularly coal, was clogging the network. The passenger service was acquiring a reputation for lateness. Lord Farrar reorganised the expresses, but by 1905 the whole system was so overloaded that no one was able to predict when many of the trains would reach their destinations. At this point Sir Guy Granet took over as General Manager. He introduced a centralised traffic control system, and the locomotive power classifications that became the model for those used by British Railways.

The MR acquired other lines, including the Belfast and Northern Counties Railway in 1903 and the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway in 1912. It had running rights on some lines, and it developed lines in partnership with other railways, being involved in more 'Joint' lines than any other. In partnership with the GN it owned the Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway to provide connections from the Midlands to East Anglia, the UK's biggest joint railway. The MR provided motive power for the Somerset & Dorset Joint Railway, and was a one-third partner in the Cheshire Lines Committee.

In 1913 the company achieved a total revenue of £15,129,136 (equivalent to £1,342,580,000 in 2015)[13] with working expenses of £9,416,981[20] (equivalent to £835,680,000 in 2015).[13]

Acquisitions

- Ashby Canal and Tramway (absorbed 1846)

- Barnoldswick Railway (leased 1871, absorbed 1899)[21]

- Bedford and Northampton Railway (leased 1872, absorbed 1885)[22]

- Northern Counties Committee (in Ireland)

- Birmingham and Gloucester Railway (leased 1845, absorbed 1846)[23]

- Birmingham West Suburban Railway (absorbed 1875)

- Bristol and Gloucester Railway (absorbed 1846)[24]

- Burton and Ashby Light Railway (leased 1906)[25]

- Chesterfield and Brampton Railway (absorbed 1871)

- Cromford Canal (absorbed 1871)[26]

- Dore and Chinley Railway (absorbed 1888)

- Erewash Valley Railway (absorbed 1845)

- Evesham and Redditch Railway (leased 1868, absorbed 1882)

- Hemel Hempsted Railway (leased 1877, absorbed 1886)

- Hereford, Hay and Brecon Railway (leased 1869, absorbed 1886)

- Keighley and Worth Valley Railway (absorbed 1881)

- Kettering, Thrapston and Huntingdon Railway (leased 1866, absorbed 1897)

- Leeds and Bradford Railway (leased 1846, absorbed 1851)

- Leeds and Bradford Extension Railway (absorbed 1851)

- Leicester and Swannington Railway (absorbed 1846)

- London, Tilbury and Southend Railway (purchased 1912, amalgamated 1920)

- Manchester, Buxton, Matlock and Midland Junction Railway (leased 1852, absorbed 1871)

- Manchester South District Railway (absorbed 1877)

- Mansfield and Pinxton Railway (absorbed 1848)[27]

- Midland and South Western Junction Railway (absorbed 1874)

- North Western Railway (also known as the "Little" North Western; leased 1859)

- Oakham Canal (absorbed 1846)

- Redditch Railway (leased 1858, absorbed 1874)

- Sheffield and Rotherham Railway (absorbed 1845)

- Stonehouse and Nailsworth Railway (absorbed 1886)[28]

- Swansea Vale Railway (leased 1874, absorbed 1876)

- Syston and Peterborough Railway (absorbed 1846)[29]

- Tewkesbury and Malvern Railway (absorbed 1876)

- Wolverhampton and Walsall Railway (absorbed 1876)[30]

- Wolverhampton, Walsall and Midland Junction Railway (absorbed 1874)[30]

Joint Lines

- Ashby and Nuneaton Line (with LNWR)

- Bourne and Lynn Railway (part of Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway)

- Bristol Port Railway and Pier (with GWR)

- Carlisle Goods Traffic Committee (with Caledonian, GSWR and LNWR)

- Clifton Extension Railway (with GWR)

- Cheshire Lines Committee (with GCR and GNR)

- Eastern and Midlands Railway (part of Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway)

- Enderby Branch Railway (with LNWR)

- Furness and Midland Joint Railway

- Halesowen Joint Railway (with GWR)

- Norfolk and Suffolk Joint Railway (with GER and GNR)

- North and South Western Junction Railway (with NLR and LNWR)

- Otley and Ilkley Railway (with NER)

- Peterborough, Wisbech and Sutton Railway (part of Midland and Great Northern Joint Railway)

- Portpatrick and Wigtownshire Railway (with Caledonian, GSWR and LNWR)

- Severn and Wye Railway (with GWR)

- Sheffield and Midland Railway Companies Committee (with GCR)

- Somerset and Dorset Railway (with LSWR)

- Swinton and Knottingley Railway (with NER)

- Tottenham and Forest Gate Railway (with LTS)

- Tottenham and Hampstead Junction Railway (with GER)

Accidents and incidents

- In June 1850, the boiler of a locomotive exploded at Kegworth railway station, Nottinghamshire.[31]

- In 1850, a train was in a rear-end collision with an excursion train at Woodlesford station, Yorkshire. The cause was a signal not being lit at night.[32]

- In 1853, the boiler of a locomotive exploded whilst it was hauling a freight train near Bristol, Gloucestershire.[31]

- On 28 August 1875, a passenger train overran signals and was in a rear-end collision with an excursion train at Kildwick, Yorkshire. Seven people were killed and 39 were injured.[32]

- On 11 August 1880, a passenger train was derailed at Wennington, Lancashire. Eight people were killed and 23 were injured.[32]

- On 19 August 1880, a passenger train stops inside Blea Moor Tunnel, Yorkshire due to a faulty brake pipe. An express passenger train overruns signals and is in a rear-end collision at low speed.[32]

- On 27 August 1887, an express passenger train overran signals and collided with a freight train that was being shunted at Wath station, Yorkshire. Twenty-two people were injured.[33]

- Main article: Esholt Junction rail crash

- On 9 June 1892, a passenger train overran signals and was in collision with another at Esholt Junction, Yorkshire. Five people were killed and 30 were injured.

- On 3 December 1892, a freight train crashed at Wymondham Junction., Leicestershire, severely damaging the signal box.[34]

- Main article: Wellingborough rail accident

- On 2 September 1898, an express passenger train was derailed at Wellingborough, Northamptonshire by a trolley that had fallen off the platform onto the track. Seven people were killed and 65 were injured.

- On 24 July 1900, a passenger train was derailed at Amberswood, Lancashire. One person was killed.[35]

- On 1 December 1900, a freight train was derailed at Peckwash near Duffield, Derbyshire.[36]

- On 23 December 1904, an express passenger train was derailed at Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire due to excessive speed on a curve. Another express passenger train collided with the wreckage at low speed. Four people were killed.[32]

- On 19 January 1905, an express passenger train overran signals and was in collision with a passenger train at Cudworth, Yorkshire. Seven people were killed.[33]

- In June 1907, a luggage train was derailed by trap points at Silkstream Junction after the driver misread signals.[37]

- Main article: Hawes Junction rail crash

- On 24 December 1910, an express passenger train was in a rear-end collision with two light engines near Moorcock Tunnel, to the south of Ais Gill summit, due to errors by the signalman at Hawes Junction and the firemen of the light engines. The train was derailed and caught fire. Twelve people were killed and seventeen were injured.

- Main article: 1913 Ais Gill rail accident

- On 2 September 1913, a passenger train overran a signal and was in a rear-end collision with another passenger train between Mallerstang and Ais Gill, i.e. to the north of Ais Gill summit. Sixteen people were killed and 38 were injured.

Ships

The MR operated ships from Heysham to Douglas and Belfast.[38]

| Ship | Launched | Tonnage (GRT) |

Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS Antrim | 1904 | 2,100[39] | Built by John Brown & Company at Clydebank, the first of a series of 4 similar ships. She was the first vessel to use the new facilities at Heysham and made her maiden voyage in September 1904. She was the first cross-channel ship with wireless. |

| SS City of Belfast | 1893 | 1,055[41] | Built by Laird Bros. of Birkenhead. Bought from Barrow Steam Navigation Co Ltd in 1907. In war service named HMS City of Belfast. Transferred to LMS in 1923. |

| SS Donegal | 1904 | 1,997[43] | A sister of Antrim built by Caird & Company of Greenock. Requisitioned during the First World War as a hospital ship. Torpedoed and sunk on 17 April 1917 near Spithead.[40][43] |

| PS Duchess of Buccleuch | 1888 | 838 | Built by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company at Govan for the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway and named Rouen. Sold to J. W. and R. P. Little for the Barrow S. N. Company and renamed Duchess of Buccleuch. Served the Barrow-Douglas route. |

| SS Duchess of Devonshire | 1897 | 1,265[44] | Built by Naval & Armament Construction Co., at Barrow for James Little and the Barrow S. N. Company. Taken over by MR in 1907. Requisitioned for war service and used as an armed boarding vessel. Suffered a boiler explosion in 1919 that killed three people. |

| SS Londonderry | 1904 | 2,086[46] | Built by William Denny and Brothers of Dumbarton, the first ship with Lodge-Muirhead wireless telegraphy. Requisitioned for trooping in 1914 and in 1923 transferred to the LMS. Sold in 1927 to Angleterre-Lorraine-Alsace, renamed Flamand. |

| SS Manxman | 1904 | 2,174[47] | Built by Vickers, Sons and Maxim Ltd of Barrow-in-Furness. Similar in design to the other 1904 built vessels but slightly longer and faster. Requisitioned in 1914 for trooping and purchased in 1915 by the Admiralty as HMS Manxman and converted to an aircraft carrier. |

| PS Manx Queen | 1880 | 989 | Built by J. & G. Thomson Ltd of Glasgow for the South Eastern Railway as the Duchess of Edinburgh. On delivery she failed to perform at the contracted design speed and after a short time in service was returned to her builders. She re-entered service in May 1841 following a compromise agreement between the builder and owner but after only five days in service she broke a paddle wheel, resulting in the owners returning her again to her builders. |

| SS Wyvern | 1905 | 232[49] | Built as a tug by Ferguson Bros. of Port Glasgow. Used for pleasure excursions from Heysham to Fleetwood until the Second World War. Transferred to London, Midland and Scottish Railway(LMS) in 1923 and British Transport Commission- London Midland Region in 1948. Scrapped in June 1960.[50] |

The MR operated vessels for port maintenance:

| Ship | Launched | Tonnage (GRT) |

Notes and references |

|---|---|---|---|

| SS Laga | 1901 | 562 | Dredger built by J and K Smit of Kinderdijk for K.L.Kalis of Sliedrecht. Purchased by MR in 1905, its first dredger. Transferred to London, Midland and Scottish Railway(LMS) in 1923 and was converted for use as a hopper barge in 1927. |

| SS Hessam | 1906 | 645 | Dredger built by Wm. Simons and Co. of Renfrew with three Priestman grab cranes. Transferred to LMS and BTC in 1923 and 1948 respectively. Withdrawn in March 1965 and broken up at Silloth the same year.[50] |

| SS Red Nab | 1908 | 537 | Hopper barge built by Wm Simons and Co. at Renfrew. Her engines had been constructed on a stand-by basis in 1907 and she was built in 1908 she had slightly smaller dimensions to give her more power. Transferred to LMS and BTC in 1923 and 1948 respectively. Renamed Red Nab ll in 1960 releasing the name to a new build. |

The MR owned several small passenger ferries formerly owned by the London, Tilbury and Southend Railway, with which it amalgamated in 1912, on the Gravesend-Tilbury Ferry. Vessels acquired were: Carlotta, Catherine (blt 1903), Edith (1911), Gertrude, Rose (1901) and Tilbury (1883).[51]

Grouping

In 1914 all the railways were taken under the control of the Railway Executive Committee.[52] By the end of the war overcrowded trains were running at only half the prewar mileage. The overworked locomotives had not had the benefit of the prewar standard of maintenance, while many of the staff never returned from the battlefront.

The MR had not recovered from this when the Government passed the Railways Act 1921, by which it was compulsorily merged with the LNWR, the Lancashire and Yorkshire, the Caledonian, the Glasgow and South Western Railway and minor lines such as the Furness and the North Staffordshire to form the London Midland and Scottish Railway on 1 January 1923.[2]

Chief posts in the Midland Railway

Chairmen

- George Hudson 1844 – 1849

- John Ellis 1849 – 1856[53]

- William Evans Hutchinson 1864 – 1870

- W.P. Price 1870 – 1873

- Edward Shipley Ellis 1873 – 1880

- Matthew W Thompson 1880 – 1890

- (George) Ernest Paget 1890 – 1911

- George Murray Smith 1911 – 1919

- Charles Booth 1919 – 1922

- (William) Guy Granet 1922 – 1923

General Managers

- Joseph Sanders 1849 – 1853 (afterwards Secretary)

- James Joseph Allport 1853 – 1857

- W. L. Newcombe 1857 – 1860

- James Joseph Allport 1860 – 1880[4]

- John Noble 1880 – 1892

- George Henry Turner 1892 – 1901

- John Mathieson 1901 – 1905

- (William) Guy Granet 1905 – 1918[3]

- Frank Tatlow 1918 – 1922 (formerly deputy general manager)

Locomotive Superintendents and Chief Mechanical Engineers

- Matthew Kirtley 1844 – 1873 (LS)

- Samuel Waite Johnson 1873 – 1904[54] (LS)

- Richard Deeley 1904 – 1909 (CME)

- Henry Fowler 1909 – 1923 (CME)

- James Anderson 1915 – 1919 (temporary)

Chief Operating Officer

Until 1907 this position was Superintendent of the Line. This position was also known as General Superintendent

- E.M Needham 1855 – 1890

- William Lowe Mugliston 1890 – 1902

- Cecil Paget 1907 – 1918

- John Henry Fellows 1919 – 1923 (afterwards with the LMS)

Resident Engineers

- William Henry Barlow 1842 – 1857[55] (afterwards Consulting Engineer)

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Barnes, E.G. (1969). The Rise of the Midland Railway 1844–1874. Augustus M. Kelley, New York. p. 308.

- 1 2 Whitehouse, Patrick; Thomas, David St John (2002). LMS 150 : The London Midland & Scottish Railway A century and a half of progress. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-1378-9.

- 1 2 E. G. Barnes (1969). The Midland main line 1875–1922, London : George Allen and Unwin, ISBN 0-04-385049-9, pp. 223–224

- 1 2

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Allport, Sir James Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Allport, Sir James Joseph". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Twells, H.N. (1985). A Pictorial Record of the Leicester and Burton Branch Railway. Burton-upon-Trent: Trent Valley Publications. ISBN 0-948131-04-7.

- ↑ "Midland Railway. Removal of the Passenger Station at Birmingham". Aris’s Birmingham Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 28 April 1851. Retrieved 12 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Vaughan, A., (1997) Railwaymen, Politics and Money, London: John Murray

- ↑ Pinton, B (2005). Birmingham-Derby: Portrait of a Famous Route. Runpast Publishing.

- ↑ "The National Archives – Great Northern Railway Company: Records". 1845. Retrieved 26 December 2010.

- ↑ Anderson, P.H., (1985 2nd ed) Forgotten Railways Vol 2: The East Midlands, Newton Abbot: David and Charles

- ↑ "Capture of a Railway Engine". Bell’s Weekly Messenger. British Newspaper Archive. 9 August 1852. Retrieved 12 July 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hadfield, Charles (1970). The Canals of the East Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4871-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2016), "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ Davies, R.; Grant, M.D. (1984). Forgotten Railways: Chilterns and Cotswolds. Newton Abbot, Devon: David St John Thomas. ISBN 0-946537-07-0, p. 110-111.

- ↑ "Local and Personal Acts", The Sessional Papers Printed by Order of The House of the Lords Or Presented by Royal Command in the Session 1863, Published 1863 (page 119)

- ↑ http://www.familygrowsontrees.com/research/railways.html[]

- ↑ Casserley, H.C. (April 1968). "Cheshire Lines Committee". Britain's Joint Lines. Shepperton: Ian Allan. pp. 68–80. ISBN 0-7110-0024-7.

- 1 2 Wolmar, Christian (2008). Fire and Steam. Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-84354-630-6.

- ↑ Evan Crawford (2 April 2012). "Nottingham and Melton Line". railscot.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ↑ "Midland Railway.". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. British Newspaper Archive. 21 February 1914. Retrieved 1 August 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Binns, Donald (1995). The Skipton-Colne Railway and The Barnoldswick Branch. Trackside Publications, Skipton, N. Yorkshire. ISBN 1900095009.

- ↑ Markham, C.A. (1970) [1904]. The Iron Roads of Northamptonshire. Wilbarston: Pilgrim Publications.

- ↑ Maggs, C (1986). The Birmingham Gloucester Line. Cheltenham: Line One Press. ISBN 0-907036-10-4.

- ↑ Maggs, Colin G. (1992) [1969]. The Bristol and Gloucester Railway and the Avon and Gloucestershire Railway (Oakwood Library of Railway History) (2nd ed.). Headington: Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-435-0. OL26.

- ↑ "Burton and Ashby Light Railway". Derby Daily Telegraph. England. 3 July 1906. Retrieved 9 February 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Hadfield, Charles (1970). The Canals of the East Midlands (2nd ed.). David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4871-X.

- ↑ Vanags, J (2001). The Mansfield and Pinxton railway. Mansfield: Old Mansfield Society. ISBN 0-9517948-5-X.

- ↑ Oakley, Mike (2003). Gloucestershire Railway Stations. Wimborne: Dovecote Press. ISBN 1-904349-24-2.

- ↑ Kingscott, G., (2006) Lost Railways of Leicestershire and Rutland, Newbury: Countryside Books

- 1 2 Christiansen, Rex (1983). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain Volume 7. ISBN 0-946537-00-3.

- 1 2 Hewison, Christian H. (1983). Locomotive Boiler Explosions. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. pp. 35–36. ISBN 0 7153 8305 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hall, Stanley (1990). The Railway Detectives. London: Ian Allan. pp. 26, 50–52, 66. ISBN 0 7110 1929 0.

- 1 2 Earnshaw, Alan (1991). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 7. Penryn: Atlantic Books. pp. 4–5, 9. ISBN 0-906899-50-8.

- ↑ Earnshaw, Alan (1990). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 6. Penryn: Atlantic Books. p. 6. ISBN 0-906899-37-0.

- ↑ Spence, Jeoffry (1975). Victorian & Edwardian Railways from old photographs. London: Batsford. p. 76. ISBN 0 7134 3044 3.

- ↑ Trevena, Arthur (1981). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 2. Redruth: Atlantic Books. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-906899-03-6.

- ↑ Earnshaw, Alan (1993). Trains in Trouble: Vol. 8. Penryn: Atlantic Books. p. 4. ISBN 0-906899-52-4.

- ↑ "Midland Railway". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 15 December 2009.

- 1 2 "1116015". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 Haws, Duncan (1993). Merchant Fleets-Britain's Railway Steamers – Eastern & North Western Companies + Zeeland and Stena. Hereford: TCL Publications. p. 118. ISBN 0-946378-22-3.

- 1 2 "1099938". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Haws 1993, p. 121

- 1 2 "1116018". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "1099941". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 Haws 1993, p. 122

- 1 2 "1116017". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 "1118603". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Haws 1993, p. 119

- ↑ "1084974". Miramar Ship Index. Retrieved 15 December 2009. (subscription required (help)).

- 1 2 3 Haws 1993, p. 120

- 1 2 Haws 1993, p. 123

- ↑ Doyle, Peter (2012). First World War Britain. Shire Publications Ltd. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-74781-098-8.

- ↑ Bilson, P (1996). Derby and the Midland Railway. Breedon Books, Derby. ISBN 1-85983-021-8.

- ↑ National Archive RAIL 491, accessed on 2014-02-21 via ancestry.co.uk UK, Railway Employment Records, 1833–1956 for Samuel Waite Johnson

- ↑ Chrimes, Mike (2008). "Barlow, William Henry (1812–1902)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/30598. Retrieved 24 December 2010. (subscription required (help)).

Sources

- Truman, P. and Hunt, D. (1989) Midland Railway Portrait, Sheffield : Platform 5, ISBN 0-906579-72-4

Further reading

- Williams, Frederick Smeeton (1876) The Midland railway: its rise and progress, Strahan & Co.

- Official Guide to the Midland Railway. London: Cassell & Company. 1894.

- Barnes, E. G. (1966), The rise of the Midland Railway, 1844–1874, London: George Allen and Unwin

- Barnes, E. G. (1969), The Midland main line, 1875–1922, London: George Allen and Unwin, ISBN 0-04-385049-9

- Talbot, Frederick A (1913). "The Waverley way to the north". Railway Wonders of the World. pp. 541–552.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Midland Railway. |