Hampton Down Stone Circle

Shown within Dorset | |

| Location | Isle of Purbeck |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 50°40′36″N 2°34′23″W / 50.676750°N 2.573132°W |

| Type | Stone circle |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic / Bronze Age |

The Hampton Down Stone Circle is a stone circle located near to the village of Portesham in the south-western English county of Dorset. Archaeologists believe that it was likely erected during the Bronze Age. The Hampton Down ring is part of a tradition of stone circle construction that spread throughout much of Britain, Ireland, and Brittany during the Late Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, over a period between 3,300 and 900 BCE. The purpose of such monuments is unknown, although archaeologists speculate that they were likely religious sites, with the stones perhaps having supernatural associations for those who built the circles.

A number of these circles were built in the area around modern Dorset, typically being constructed from sarsen stone and being smaller than those found elsewhere. By 1908 the circle had been shifted east of its original position, with a hedge built across the site, and the number of stones increased to sixteen. By 1964 the number of stones had further increased to twenty-eight. In 1965, G. C. Wainwright oversaw an archaeological excavation which revealed the circle's original location and dimensions, after which it was reconstructed in its original location with the extraneous stones removed.

Location

Positioned at the national grid reference 35960865,[1] Hampton Down Stone Circle is located on the southern edge of an open down-land ridge at a height of 680 feet above sea level.[2] Located 1km north-west of Portesham,[1] it is positioned on the rim of Portesham Hill and overlooks the coast.[3] Had the vegetation levels been low at the time of the circle's creation then it would have permitted extensive panoramic views of the coastline.[4] The stones are sarsen.[5] It is located on private land.[1]

Context

While the transition from the Early Neolithic to the Late Neolithic—which took place with the transition from the fourth to the third millennium BCE—witnessed much economic and technological continuity, it also saw a considerable change in the style of monuments erected, particularly in southern and eastern England.[6] By 3000 BCE, the long barrows, causewayed enclosures, and cursuses which had predominated in the Early Neolithic had ceased being built, and were instead replaced by circular monuments of various kinds.[6] These include earthen henges, timber circles, and stone circles.[7] These latter circles are found in most areas of Britain where stone is available, with the exception of the island's south-eastern corner.[8] They are most densely concentrated in south-western Britain and on the north-eastern horn of Scotland, near Aberdeen.[8]

These stone circles typically show very little evidence of human visitation during the period immediately following their creation.[10] This suggests that they were not sites used for rituals that left archaeologically visible evidence, and may have been deliberately left as "silent and empty monuments".[11] The archaeologist Mike Parker Pearson suggested that in Neolithic Britain, stone was associated with the dead and wood with the living.[12] Other archaeologists have suggested that the stone might not represent ancestors, but rather other supernatural entities, such as deities.[11]

The area of modern Dorset has only a "thin scatter" of stone circles,[13] with nine possible examples known within its boundaries.[14] The archaeologist John Gale described these as "a small but significant group" of such monuments,[14] and all are located within five miles of the sea.[3] All but one—Rempstone Stone Circle on the Isle of Purbeck—are located on the chalk hills west of Dorchester.[15] The Dorset circles have a simplistic typology, being of comparatively small size, with none exceeding 28 metres in diameter.[16] All are oval in shape, although perhaps have been altered from their original form.[17] With the exception of the Rempstone circle, all consist of sarsen stone.[15] Much of this may have been obtained from the Valley of Stones, a location at the foot of Crow Hill near to Littlebredy, which is located within the vicinity of many of these circles.[18] With the exception of the circle at Litton Cheney, none display evidence of any outlying stones or earthworks around the stone circle.[19]

The archaeologists Stuart and Cecily Piggott believed that the circles of Dorset were probably of Bronze Age origin,[20] a view endorsed by Burl, who noted that their distribution did not match that of any known Neolithic sites.[21] It is possible that they were not all constructed around the same date,[22] and the Piggotts suggested that while they may well be Early Bronze Age in date, it is also possible that "their use and possibly their construction may last into the Middle and even into the Late Bronze Age".[20] Their nearest analogies are the circles found on Dartmoor and Exmoor to the west, and the Stanton Drew stone circles to the north.[23] It is also possible that the stone circles were linked to a number of earthen henges erected in Dorset around the same period.[20]

Description

The archaeologist Aubrey Burl described the circle as a "megalithic chameleon".[24] A photograph from 1908 showed sixteen stones as part of the monument, a number that was again recorded by the Piggotts in 1938. However, by 1964 twenty-eight stones were found to be part of the circle.[25] Investigations found that when the field to the east of the hedge was cleared in 1964, a large number of stones had been found on the surface and had been moved to the site of the other stones.[26] It is possible that these other stones had also once been part of a prehistoric monument, such as a long barrow or round barrow, which had once existed in the vicinity.[26]

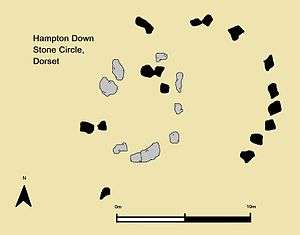

Commenting on the site in 1939, the archaeologists Stuart Piggott and Cecily Piggott opined that ten stones in the eastern half were likely in their original position.[20] As of 1939, a hedge and bank split the circle in two, from north-to-south, separating the three most westerly stones from the rest of the circle.[20] They expressed the view that "owing to [the stone's] rough cube-like shapes it is impossible to decide whether they are upright or recumbent".[20] Based on what they believed to be the sites in their original position, they estimated the circle's original diameter at 35 feet (11-12m).[27]

Excavation

In 1964 the stones in the circle were disturbed by agricultural operation.[28] It was then decided that the site would be excavated, a project which was ordered by the Ministry of Public Building and Works and carried out in May 1965 under the directorship of Geoffrey J. Wainwright.[29] The 28 stones were moved from the site using a crane to permit the archaeologists to excavate the area beneath them.[28]

The excavation revealed that the location of the stones was not their original prehistoric position.[30] The original location of the circle was identified as existing a few feet to the west, under an adjacent hedge.[4] The original circle had either eight or possibly nine sockets for stones and was oval shaped.[30] The perimeter of the ring was defined by V-shaped ditches on its eastern and western perimeters.[30] The maximum axis of the circle would have been approximately 20 feet (6.5 metres),[30] making it considerably smaller than the size proposed by the Piggotts.[31] There was a 4 feet (1.2 m) wide track leading to the circle from the north,[32] with Burl opining that "if this had been an avenue it was a very poor one".[3] Three stake-holes were found at the western side of the circle, where it was joined by the track.[29]

If used as a space for rituals, the Hampton Down circle would have only been able to accommodate a few individuals standing within it at any given time.[21] It was also not the site of any cremation deposits, unlike some stone circles in Northern Britain.[21] Burl suggested that the Hampton Down Stone Circle may never have been part of the prehistoric stone circle tradition, but that the stones were actually once the kerbstones of a round barrow.[33] To support this suggestion, he noted that round barrows were known at Poole, around 20 miles to the east of the site.[33]

No finds were found during the excavation,[34] and thus it produced no means of securely dating the construction of the site.[35] Wainwright suggested that it was Early Bronze Age on the basis of other, dated circles in Britain.[36] Based on the site's stratigraphy, he argued that the stones had likely been removed from their original position amid agricultural development in the second half of the seventeenth century.[30] According to Burl, "its history illuminates the perils of superficial fieldwork".[3] As of 2003, it was the only one of the Dorset circles to have seen excavation.[14]

Following excavation, several stones were placed in the original sockets in order to create a reconstruction of the original circle.[37] A fence was then erected around the circle to discourage further interference.[36]

References

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Gale 2003, p. 158.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 142; Wainwright 1967, p. 122.

- 1 2 3 4 Burl 2000, p. 308.

- 1 2 Gale 2003, p. 73.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 142; Gale 2003, p. 158.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 81.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 91–94.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 94.

- ↑ Anonymous 1908, pp. 74, 78.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, p. 97.

- 1 2 Hutton 2013, p. 98.

- ↑ Hutton 2013, pp. 97–98.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 307.

- 1 2 3 Gale 2003, p. 72.

- 1 2 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 138.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 139; Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, p. 72.

- ↑ Burl 2000, p. 308; Gale 2003, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 142.

- 1 2 3 Burl 2000, p. 310.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 141.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 140.

- ↑ Burl 2005, p. 67.

- ↑ Wainwright 1967, p. 124; Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 121; Burl 2000, pp. 308–309; Burl 2005, p. 67.

- 1 2 Wainwright 1968, p. 124.

- ↑ Piggott & Piggott 1939, p. 142; Gale 2003, p. 73.

- 1 2 Wainwright 1967, p. 124.

- 1 2 Wainwright 1967, p. 124; Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Wainwright 1967, p. 124; Gale 2003, p. 73.

- ↑ Gale 2003, p. 74.

- ↑ Wainwright 1967, p. 124; Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 121; Burl 2000, p. 308.

- 1 2 Burl 2005, p. 68.

- ↑ Wainwright 1967, p. 124; Thom, Thom & Burl 1980, p. 121; Burl 2000, p. 309.

- ↑ Wainwright 1967, p. 127; Gale 2003, p. 76.

- 1 2 Wainwright 1967, p. 127.

- ↑ Wainwright 1967, p. 127; Gale 2003, p. 158.

Bibliography

- Anonymous (1908). "Third Summer Meeting: Portesham and Bridehead District". Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society. 29: 73–81.

- Burl, Aubrey (2000). The Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08347-7.

- Burl, Aubrey (2005). A Guide to the Stone Circles of Britain, Ireland and Brittany. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-11406-5.

- Gale, John (2003). Prehistoric Dorset. Stroud: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2906-9.

- Hutton, Ronald (2013). Pagan Britain. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-19771-6.

- Piggott, Stuart; Piggott, C. M. (1939). "Stone and Earth Circles in Dorset". Antiquity. 13 (50). pp. 138–158. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00027861.

- Thom, Alexander; Thom, Archibald Stevenson; Burl, Aubrey (1980). Megalithic Rings: Plans and Data for 229 Monuments in Britain. BAR British Series 81. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports. ISBN 0-86054-094-4.

- Wainwright, G. J. (1967). "The Excavation of Hampton Stone Circle, Portesham, Dorset". Proceedings of the Dorset Natural History and Archaeological Society. 88. pp. 122–127.