HMCS Oakville

HMCS Oakville seen on 7 August 1943 near Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, while on passage from Saint John, New Brunswick, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, as an escort to convoy FH-70 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Oakville |

| Namesake: | Oakville, Ontario |

| Ordered: | 1 February 1940 |

| Builder: | Port Arthur Shipbuilding Co., Port Arthur |

| Laid down: | 21 December 1940 |

| Launched: | 21 June 1941 |

| Commissioned: | 18 November 1941 |

| Decommissioned: | 20 July 1945 |

| Identification: | Pennant number: K178 |

| Honours and awards: | Atlantic 1942-45[1] |

| Fate: | Sold in 1946 to Venezuela as Patria. |

| Name: | Patria |

| Acquired: | purchased from Royal Canadian Navy |

| Commissioned: | 1946 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Flower-class corvette[2] |

| Displacement: | 925 long tons (940 t; 1,036 short tons) |

| Length: | 205 ft (62.48 m)o/a |

| Beam: | 33 ft (10.06 m) |

| Draught: | 11.5 ft (3.51 m) |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 16 knots (29.6 km/h) |

| Range: | 3,500 nautical miles (6,482 km) at 12 knots (22.2 km/h) |

| Complement: | 85 |

| Sensors and processing systems: |

|

| Armament: |

|

HMCS Oakville was a Royal Canadian Navy Flower-class corvette which took part in convoy escort duties during the Second World War. She fought primarily in the Battle of the Atlantic. After the war she was sold to the Venezuelan Navy. She was named after Oakville, Ontario.

Background

Flower-class corvettes like Oakville serving with the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War were different from earlier and more traditional sail-driven corvettes.[3][4][5] The "corvette" designation was created by the French as a class of small warships; the Royal Navy borrowed the term for a period but discontinued its use in 1877.[6] During the hurried preparations for war in the late 1930s, Winston Churchill reactivated the corvette class, needing a name for smaller ships used in an escort capacity, in this case based on a whaling ship design.[7] The generic name "flower" was used to designate the class of these ships, which – in the Royal Navy – were named after flowering plants.[8]

Corvettes commissioned by the Royal Canadian Navy during the Second World War were named after communities for the most part, to better represent the people who took part in building them. This idea was put forth by Admiral Percy W. Nelles. Sponsors were commonly associated with the community for which the ship was named. Royal Navy corvettes were designed as open sea escorts, while Canadian corvettes were developed for coastal auxiliary roles which was exemplified by their minesweeping gear. Eventually the Canadian corvettes would be modified to allow them to perform better on the open seas.[9]

Construction and career

Oakville was laid down by Port Arthur Shipbuilding Co. at Port Arthur on 21 December 1940 and was launched on 21 June 1941. She was commissioned into the RCN on 18 November 1941.

Attempted capture and sinking of U-94

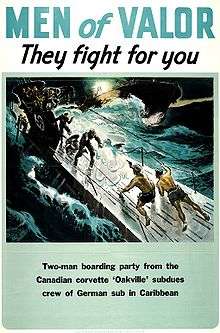

On 28 August 1942, in the company of American warships and the corvettes Halifax and Snowberry, Oakville was escorting a convoy off Haïti when she attacked U-94. The submarine, which had been on the point of attacking the convoy, was first spotted and bombarded by an American seaplane. Oakville dropped depth charges to force it to surface, and after bombarding it, rammed the submarine twice. The submarine, struck by a depth charge on the surface, gave up the fight. A boarding party was dispatched to seize the vessel.

Eleven sailors, under the command of Commander Clarence King, including Sub Lieutenant Hal Lawrence, and Petty Officer A.J. Powell, leapt onto the deck of the crippled U-94 and rushed toward the conning tower, which was riddled by shellfire.[10] After clearing away the dead bodies covering the hatchway, Lawrence and Powell headed below. They were then surprised by two Germans who emerged from an escape hatch. After ordering them back inside, the Canadians opened fire on the two men, who were dashing toward them.

The German crew, in a panic at the thought that the U-boat could sink at any moment, surrendered quickly. Despite the danger, Lawrence went searching for the Enigma machine and documents. But finding that U-94 had been scuttled, he retraced his steps, having to swim to the ladder which led to the conning tower. After giving the order to abandon ship, Lawrence leapt into the water just before the submarine went down. The Allied sailors and the 19 German survivors were recovered by Oakville and the American destroyer Lea.[11]

Post-war service

Oakville was paid off from the RCN and decommissioned on 20 July 1945. She was sold in 1946 to Venezuela as Patria. The ship's bell disappeared prior to the sale and remains missing.

References

Notes

- ↑ "Battle Honours". Britain's Navy. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Colledge, J. J.; Warlow, Ben (2006) [1969]. Ships of the Royal Navy: The Complete Record of all Fighting Ships of the Royal Navy (Rev. ed.). London: Chatham Publishing. p. 184. ISBN 978-1-86176-281-8. OCLC 67375475.

- ↑ Ossian, Robert. "Complete List of Sailing Vessels". The Pirate King. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- ↑ Fitzsimons, Bernard, ed. (1978). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of 20th Century Weapons & Warfare. 11. London: Phoebus. pp. 1137–1142.

- ↑ Jane's Fighting Ships of World War II. New Jersey: Random House. 1996. p. 68. ISBN 0-517-67963-9.

- ↑ Blake, Nicholas; Lawrence, Richard (2005). The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy. Stackpole Books. pp. 39–63. ISBN 0-8117-3275-4.

- ↑ Chesneau, Roger; Gardiner, Robert (June 1980). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships (1922-1946). Naval Institute Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-87021-913-8.

- ↑ Milner, Marc (1985). North Atlantic Run. Naval Institute Press. pp. 117–119, 142–145, 158, 175–176, 226, 235, 285–291. ISBN 0-87021-450-0.

- ↑ Macpherson, Ken; Milner, Marc (1993). Corvettes of the Royal Canadian Navy 1939-1945. St. Catharines: Vanwell Publishing. ISBN 1-55125-052-7.

- ↑ "Two Canadians board U-Boat, capture crew at gunpoint". Toronto Evening Telegram. 10 November 1942. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- ↑ "August 28, 1942". The Maple Leaf. 9 (29). 23 August 2006. Archived from the original on 1 April 2012. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

References

- Livingston, Sean E. (2014). Oakville's Flower: The History of HMCS Oakville. Toronto: Dundurn Press.

External links

- HMCS Oakville (K178) on the Arnold Hague database at convoyweb.org.uk.

- Canadian Navy Heritage Project: Ship Technical Information

- Canadian Navy Heritage Project: Photo Archive