Granada medium

Granada medium is a selective and differential culture medium designed to selectively isolate Streptococcus agalactiae (Group B streptococcus, GBS) and differentiate it from other microorganisms. Identification of GBS on granada medium is straightforward and relies on detection of granadaene, a red polyenic pigment specific of GBS.[1][2]

Composition[3]

| Ingredient | Amount | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Agar | 10g | Gelling agent |

| Bacto™ Proteose Peptone #3, (Difco) BD | 25g | Specific nutrient, It cannot be substituted by any alternative peptone |

| Starch | 20g | Pigment stabilizer |

| Glucose | 2.5g | Nutrient |

| Horse serum | 15ml | Nutrient |

| MOPS ( 3-(N-morpholino)propanesulfonic acid) hemisodium salt | 11g | Good buffer |

| Disodium hydrogen phosphate | 8.5g | Buffering agent |

| Sodium pyruvate | 1g | Additional source of energy. Protective effects against reactive oxygen species (ROS) |

| Magnesium sulfate | 0.2g | ------ |

| Methotrexate | 6 mg | Pigment enhancer |

| Crystal violet | 0.2 mg | Inhibit the growth of gram-positive bacteria |

| Colistin sulfate | 5 mg | Inhibit the growth of gram-negative bacteria |

| Metronidazole | 1 mg | Inhibit the growth of anaerobic bacteria |

| Water | 1000ml |

pH 7.45±0.1

Background and principles

Granada medium was developed for selective isolation and identification of GBS from clinical specimens [3] at the Service of Microbiology in the Hospital Virgen de las Nieves in Granada (Spain). Production of a red pigment (granadaene) on granada medium is unique to β-hemolytic group B streptococci isolated from humans.[4] Granadaene is a non-isoprenoid polyenic pigment (ornithinrhamnododecaene) with a conjugated system of 12 double bonds.[2][5][6] β-hemolysis and pigment production are encoded in GBS by a gene cluster of 12 genes, the cyl cluster.[7][8] Moreover, it has been suggested that GBS pigment and hemolysin are identical or closely related molecules and it has also been reported that they are important factors contributing to GBS virulence.[4][9][10] Nevertheless, 1-5% of GBS strains are non-hemolytic and do not produce pigment.,[4] however these non-hemolytic and non-pigmented GBS strains (lacking pigment and hemolysin) are considered less virulent.[9][10][11][12][13]

Components

Granada agar consists primarily of a proteose peptone starch agar buffered with MOPS (a Good's buffer) and phosphate and supplemented with methotrexate and antibiotics.[3] Proteose peptone, horse serum, glucose and sodium pyruvate provide nutrients for the growth of Streptococcus agalactiae, sodium pyruvate provide also protective effect against reactive oxygen species (ROS). MOPS and phosphate buffer the medium. Methotrexate triggers pigment production[4] and starch stabilizes the pigment.[4] The selective supplement contains the antibiotics, colistin (inhibitory for gram-negative bacteria) and metronidazole (inhibitory for anaerobic bacteria), and crystal violet to suppress the accompanying gram-positive bacteria.

A key component of granada medium is Proteose Peptone N3 (Difco & BD). This pepsic peptone was developed by DIFCO (Digestive Ferments Company) during the First World War for producing bacterial toxins for vaccine production. [14] Fort development of red-brick colonies of GBS in granada medium it is necessary the presence of the peptide Ile-Ala-Arg-Arg-His-Pro-Tyr-Phe in the culture medium. This peptide only is produced during the hydrolysis with pepsin of mammal albumin. [15] For optimal production of pigment it is also necessary the presence in the peptone of other substances (uncharacterized at present) from mammal gastrointestinal wall tissues used to prepare some peptones. [16] The presence of starch is a basic requirement to stabilize the pigment allowing the development of red colonies of GBS. [4] Nevertheless, if soluble starch is used it results in a culture medium that deteriorates quickly at room temperature because soluble starch is hydrolysed by serum (added as supplement) amylase.This drawback can be addressed either not using serum or using unmodified starches to prepare the culture medium, because unmodified starches are more resistant to the hydrolytic action of amylase. [17]

Uses

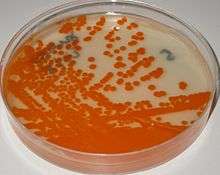

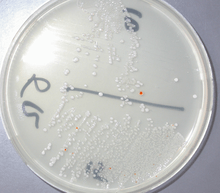

GBS grows on granada agar as pink-red colonies after 18–48 hours of incubation (35-37 °C), better results are obtained in anaerobiosis (culturing in an anaerobic environment).[3] Granada agar is used for the primary isolation, identification and screening of β-hemolytic GBS from clinical specimens.[1]

This culture medium is selective for GBS, nevertheless other microorganisms (such as enterococci and yeasts), resistant to the selective agents used, can develop as colorless or white colonies.[1]

Granada agar is useful for the screening of pregnant women for the detection of vaginal and rectal colonization with GBS to use intrapartum antibiotic prophylaxis to avoid early-onset GBS infection in the newborn.[18][19]

Procedure

The specimens can be directly streaked on a plate of granada agar or after an enrichment step to obtain maximum isolation.[18] Specimens should be streaked as soon as possible after they are received in the laboratory. If material is being cultured from a swab (e.g.- from a vaginal or vagino-rectal swab), roll swab directly onto the agar plate to provide adequate exposure of the swab to the medium for maximum transfer of organisms.

Place the culture in an anaerobic environment, incubate at 35-37 °C, and examine after overnight incubation, and again after approximately 48 hours.[3]

To increase recovery of GBS, swabs can also be inoculated previously into a selective enrichment broth medium, such as the Todd-Hewitt broth supplemented with gentamicin or colistin and nalidixic acid and incubated for 18–24 hours at 35-37 °C.[18]

Results

Colonies of β-hemolytic GBS appear on granada medium as pink or red colonies, and they are easily distinguished from other microorganisms that may have also grown on the plate. Any degree of orange development should be considered indicative of a GBS colony, and further identification tests are not necessary.[1] Non-β-hemolytic GBS develops on granada agar as white colonies that, if necessary, can be further tested using latex agglutination or the CAMP test.[18][19]

Variant

Granada agar plates can also be incubated aerobically provided that a coverslip is placed over the inoculum on the plate.[1] Granada medium can also be used as granada broth[19] (granada biphasic broth[20] and Strep B carrot broth [21]). When using granada media liquids anaerobic incubation is not necessary.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rosa-Fraile M, Rodriguez-Granger J, Cueto-Lopez M, Sampedro A, Biel Gaye E, Haro M, Andreu A (1999). "Use of Granada Medium To Detect Group B Streptococcal Colonization in Pregnant Women" (PDF). J Clin Microbiol. 37: 2674–2677.

- 1 2 Rosa-Fraile M, Rodriguez-Granger J, Haidour-Benamin A, Cuerva JM, Sampedro A (2006). "Granadaene: Proposed Structure of the Group B Streptococcus Polyenic Pigment" (PDF). Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72: 6367–6370. doi:10.1128/aem.00756-06.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosa M, Perez M, Carazo C, Peis JI, Pareja L, Hernandez F (1992). "New Granada Medium for Detection and Identification of Group B Streptococci." (PDF). J Clin Microbiol. 30: 1019–1021. PMC 265207

. PMID 1572958.

. PMID 1572958. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Rosa-Fraile M, Dramsi S, Spellerberg B (2014). "Group B streptococcal haemolysin and pigment, a tale of twins" (PDF). FEMS Microbiol Rev. 38: 932–946. doi:10.1111/1574-6976.12071.

- ↑ Paradas M, Jurado R, Haidour A, Rodríguez Granger J, Sampedro Martínez A, de la Rosa Fraile M, Robles R, Justicia J, Cuerva JM (2012). "Clarifying the structure of granadaene: total synthesis of related analogue [2]-granadaene and confirmation of its absolute stereochemistry.". Bioorg Med Chem. 20: 6655–6651. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2012.09.017.

- ↑ Madden KS, Mosa FA, Whiting A (2014). "Non-isoprenoid polyene natural products – structures and synthetic strategies". Bioorg Med Chem. 12: 7877–7899. doi:10.1039/C4OB01337A.

- ↑ Spellerberg B, Pohl B, Haase G, Martin S, Weber-Heynemann J, Lutticken R (1999). "Identification of Genetic Determinants for the Hemolytic Activity of Streptococcus agalactiae by ISS1 Transposition." (PDF). J. Bacteriol. 181: 3212–3219. PMC 93778

. PMID 10322024.

. PMID 10322024. - ↑ Spellerberg B, Martin S, Brandt C, Lutticken R (2000). "The cyl genes of Streptococcus agalactiae are involved in the production of pigment." (PDF). FEMS Microbiol Lett. 188: 125–128. doi:10.1016/s0378-1097(00)00224-x.

- 1 2 Whidbey C, Harrell MI, Burnside K, Ngo L, Becraft AK, Iyer LM, Aravind L, Hitti J, Adams Waldorf KM, Rajagopal L (2013). "A hemolytic pigment of Group B Streptococcus allows bacterial penetration of human placenta." (PDF). J Exp Med. 210: 1265–1281. doi:10.1084/jem.20122753. PMC 3674703

. PMID 23712433.

. PMID 23712433. - 1 2 Whidbey C, Vornhagen J, Gendrin C, Boldenow E, Samson JM, Doering K, Ngo L, Ezekwe EA Jr, Gundlach JH, Elovitz MA, Liggitt D, Duncan JA, Adams Waldorf KM, Rajagopal L (2015). "A streptococcal lipid toxin induces membrane permeabilization and pyroptosis leading to fetal injury." (PDF). EMBO Mol Med. 7: 488–505. doi:10.15252/emmm.201404883. PMC 4403049

. PMID 25750210.

. PMID 25750210. - ↑ Christopher-Mychael Whidbey (2015). Characterization of the Group B Streptococcus Hemolysin and its Role in Intrauterine Infection (PDF). University of Washington. Retrieved 23 June 2016.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Granger J, Spellerberg B, Asam D, Rosa-Fraile M. (2015). "Non-haemolytic and non-pigmented group b streptococcus, an infrequent cause of early onset neonatal sepsis.". Pathog Dis. 73. doi:10.1093/femspd/ftv089.

- ↑ Leclercq SY, Sullivan MJ, Ipe DS, Smith JP, Cripps AW, Ulett GC. (July 7, 2016). "Pathogenesis of Streptococcus urinary tract infection depends on bacterial strain and β-hemolysin/cytolysin that mediates cytotoxicity, cytokine synthesis, inflammation and virulence". Sci Rep. doi:10.1038/srep29000.

- ↑ Difco & BBL. Manual of Microbiological Culture Media 2nd Edition. BD Diagnostics – Diagnostic Systems. 2009. p. 450. ISBN 0-9727207-1-5.

- ↑ Rosa-Fraile M, Sampedro A, Varela J, Garcia-Peña M, Gimenez-Gallego G. (1999). "Identification of a peptide from mammal albumins responsible for enhanced pigment production by group B streptococci." (PDF). Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 6: 425–426.

- ↑ Enrique Camacho Muñoz (2005). Importancia de la Proteosa Peptona No 3 en la Producción de Pigmento por Streptococcus agalactiae en el Medio Granada (PDF). Universidad de Granada. ISBN 84-338-3741-9. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Rosa-Fraile M, Rodríguez-Granger J, Camacho-Muñoz E, Sampedro A. (2005). "Use of unmodified starches and partial removal of serum to improve Granada medium stability." (PDF). J Clin Microbiol. 43: 18889–1991.

- 1 2 3 4 Verani JR, McGee L, Schrag SJ (2010). "Prevention of Perinatal Group B Streptococcal Disease Revised Guidelines from CDC, 2010." (PDF). MMWR Recomm Rep. 59. (RR-10): 1–32.

- 1 2 3 Carey RB. "Group B Streptococci: Chains & Changes New Guidelines for the Prevention of Early-Onset GBS" (PDF). Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- ↑ "BIOMERIEUX--Granada Biphasic broth". Retrieved 26 Oct 2015.

- ↑ "HARDY-STREP B CARROT BROTH". Retrieved 26 Oct 2015.