Francoist Spain

| Spanish State Kingdom of Spain | ||||||||||||||||

| Estado Español Reino de España | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Motto Una, Grande y Libre "One, Great and Free" | ||||||||||||||||

| Anthem Marcha Granadera "Grenadier March" | ||||||||||||||||

Territories and colonies of the Spanish State:

| ||||||||||||||||

| Capital | ||||||||||||||||

| Languages | Spanish (official; sole legal language) | |||||||||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||||||||||||

| Government | Francoist one-party state | |||||||||||||||

| Caudillo (Head of State) | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1936–1975 | Francisco Franco | ||||||||||||||

| Prime Minister | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1936 | Miguel Cabanellas (first) | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1938–1973 | Francisco Franco | ||||||||||||||

| • | 1973–1975 | Carlos A. Navarro (last) | ||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Cortes Españolas | |||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Interwar period / Cold War | |||||||||||||||

| • | Spanish Civil War | 1936–1939 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Establishment | 1 October 1936 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Republic exiled | 1 April 1939 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Law of Succession | 1947 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Ifni War | 23 Oct 1957 – 30 Jun 1958 | ||||||||||||||

| • | Death of Franco | 20 November 1975 | ||||||||||||||

| Area | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1940[1] | 796,030 km² (307,349 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||

| Population | ||||||||||||||||

| • | 1940[2] est. | 25,877,971 | ||||||||||||||

| Density | 32.5 /km² (84.2 /sq mi) | |||||||||||||||

| • | 1975 est. | 35,563,535 | ||||||||||||||

| Density | 44.7 /km² (115.7 /sq mi) | |||||||||||||||

| Currency | Spanish peseta | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| a. Formally, Franco was titled "Caudillo de España, Por la Gracia de Dios" and was de facto the leader of Spain. | ||||||||||||||||

"Francoist Spain" (also historically "Nationalist Spain" during the Spanish Civil War) refers to the period of Spanish history between 1939, when Francisco Franco took control of Spain from the government of the Second Spanish Republic after winning the Civil War, and 1978, when the Spanish Constitution of 1978 went into effect. It is the opinion of several historians that during the Spanish Civil War, Franco's goal was to turn Spain into a totalitarian state like Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. However, its entry into the war on the Axis side was prevented largely by, as was much later revealed, British Secret Intelligence Service (MI-6) efforts that included up to $200 million in bribes for Spanish officials to keep the regime from getting involved.[3] Franco was also able to take advantage of the resources of the Axis Powers and chose to avoid becoming heavily involved in the Second World War. Franco's regime evolved into a more classical autocratic regime.[4]

The Spanish Civil War started as a coup by the Spanish military on the peninsula (peninsulares) and in Spanish Morocco (africanistas) on July 17, 1936.[5] The coup had the support of most factions sympathetic to the right-wing cause in Spain, including the majority of Spain's Catholic clergy, the fascist-inclined Falange, and the Alfonsine and Carlist monarchists. The coup escalated into a civil war lasting for three years once Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany agreed to support Franco, starting with airlifting of the africanistas onto the mainland.[6] Other supporters included Portugal's Estado Novo regime under António de Oliveira Salazar, while the presentation of the Civil War as a "crusade"[7] or renewed reconquista[8][9][10] attracted the sympathy of Catholics internationally and the participation of Irish Catholic volunteers. Although the government of the United Kingdom was more sympathetic[11][12][13] to the Francoists while the Popular Front government of France was anxious to support the Republic, both factions observed the non-intervention agreement of October 1936. The Second Spanish Republic was backed by the Stalinist Soviet Union and Mexico, at the time the Soviet Union's only ideological ally, from December 1936, but the help was much less than that provided to Nationalist Spain.[14]

Establishment

On 1 October 1936 Franco was formally recognised as Caudillo for the Spanish patria—the Spanish equivalent of the Italian duce and the German Führer—by the National Defense Committee (Junta de defensa nacional), which governed the territories occupied by the Nationalists.[15] In April 1937 Franco assumed control of the Falange, then led by Manuel Hedilla, who had succeeded the founder José Antonio Primo de Rivera, who was executed in November 1936 by the Republican government then in power. He consolidated it along with the monarchist Carlists into what was known as the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS, the official party of the Francoists, referred to as the Movimiento, especially in the later years of the regime.[16] The Falangists were concentrated at local government and grassroot level, entrusted with harnessing the Civil War's momentum of mass mobilisation through their auxiliaries and syndicates by collecting denunciations of enemy residents and recruiting workers into the syndicates.[17][18] While there were prominent Falangists at a senior government level, especially before the late 1940s, there were higher concentrations of monarchists, military officials and other traditional conservative factions at those levels. However, the Falange remained the sole party throughout Franco's regime and its ideology, National Syndicalism, remained the official ideology of the State.

The Francoists took control of Spain through a comprehensive and methodical war of attrition (guerra de desgaste) which involved the imprisonment and executions of Spaniards found guilty of supporting the values promoted (at least in theory) by the Republic: regional autonomy, liberal or social democracy, free elections, and women's rights, including the vote.[19][20] The rightists considered these "enemy elements" to comprise an "anti-Spain" that was the product of Bolsheviks and a "Judeo-Masonic conspiracy", which had evolved after the reconquista ("reconquest") of (Christian) Spain from the Islamic Moors, a reconquista that had been declared formally over with the Alhambra Decree of 1492 expelling the Jews from Spain.[21] At the end of the Spanish Civil War, according to the regime's own figures, there were more than 270,000 men and women held in prisons, and some 500,000 had fled into exile. Large numbers of those captured were returned to Spain or interned in Nazi concentration camps as stateless enemies. Between six and seven thousand exiles from Spain died in Mauthausen. It has been estimated that more than 200,000 Spaniards died in the first years of the dictatorship, from 1940–42, as a result of political repression, hunger, and disease related to the conflict.[22]

Spain's strong ties with the Axis resulted in its international ostracism in the early years following World War II; Spain was not a founding member of the United Nations, and did not become a member until 1955.[23] This changed with the Cold War that soon followed the end of hostilities in 1945, in the face of which Franco's strong anti-communism naturally tilted its regime to ally with the United States. Independent political parties and trade unions were banned throughout the duration of the dictatorship.[24] Nevertheless, once decrees for economic stabilisation were put forth by the late 1950s, opening the way for massive foreign investment – "a watershed in post-war economic, social and ideological normalisation leading to extraordinarily rapid economic growth" – that marked Spain's "participation in the Europe-wide post-war economic normality centred on mass consumption and consensus, in contrast to the concurrent reality of the Soviet bloc."[25]

On July 26, 1947 Spain was declared a kingdom, but no monarch was designated until in 1969 Franco established Juan Carlos de Borbón as his official heir-apparent. Franco was to be succeeded by his Prime Minister Luis Carrero Blanco as head of government with the intention of continuing the Francoist regime, but those hopes ended with his 1973 assassination. With the death of Franco on 20 November 1975, Juan Carlos became the King of Spain. He initiated the country's subsequent transition to democracy, ending with Spain becoming a constitutional monarchy with an elected parliament.

Government

After Franco's victory in 1939, the Falange (the FET y de las JONS formed in 1937 by the FE de las JONS, the Carlists, and several conservative groups) was declared the sole legal party in Spain, and it asserted itself as the main component of the Movimiento Nacional. In a state of emergency-like status, the 100-member national council (central committee) of the FET worked as makeshift legislature of Spain until the passing of the Organic law of 1942 (Ley Orgánica) and the Constituting of the Cortes Act (Ley Constitutiva de las Cortes) the same year, which saw the grand reopening of the Cortes on July 18, 1942.[26]

The Organic Law made the government ultimately responsible for passing all laws,[27] while defining the Cortes of Spain as a purely advisory body elected by neither direct nor universal suffrage. As all ministers were appointed and dismissed by Franco as the "Chief" of state and government, he was effectively the only source of legislation. The law of national referendums (Ley del Referendum Nacional), passed in 1945 approved for all "fundamental laws" to be approved by a popular referendum, in which only the heads of families could vote. Local municipal councils were appointed similarly by heads of families and local corporations through elections, while mayors were appointed by the government. It was thus one of the most centralized countries in Europe, and certainly the most centralized in Western Europe following the fall of Portuguese dictator Marcelo Caetano in the Carnation Revolution.

The referendum law was used twice during Franco's rule—in 1947, when a referendum revived the Spanish monarchy with Franco as de facto regent for life with sole right to appoint his successor, and in 1966, to approve of a new "organic law", or constitution, supposedly limiting and clearly defining Franco's powers as well as formally creating the modern office of President of the Government of Spain. By delaying the issue of republic versus monarchy for his 36-year dictatorship, and by refusing to take up the throne himself in 1947, Franco sought to antagonize neither the monarchical Carlists (who preferred the restoration of a Bourbon), nor the republican "old shirts", i.e., the original Falangists. In 1961, Franco offered Otto von Habsburg the throne, but was refused, and ultimately followed Otto's recommendation by selecting the young Juan Carlos of Bourbon in 1969 as his officially designated heir to the throne, shortly after his 30th birthday (the minimum age required under the Law of Succession).

On 1973, due to old age and to lessen his burdens in governing Spain, Franco resigned as the country's President of the Government or Prime Minister and named Navy Admiral Luis Carrero Blanco to the said post but he remained as the Chief of State, Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces and Head of the Movimiento Nacional. However, Carrero Blanco was assassinated on the same year and Franco named a civilian, Carlos Arias Navarro as the country's new Prime Minister.

Armed forces

During the first year of peace, Franco dramatically reduced the size of the Spanish Army; from almost one million at the end of the civil war to 250,000 in early 1940, with most soldiers two-year conscripts.[28] Concerns about the international situation, Spain's possible entry into World War II, and threats of invasion led him to undo some of these reductions. In November 1942, with the Allied landings in North Africa and the German occupation of Vichy France bringing hostilities closer than ever to Spain's border, Franco ordered a partial mobilization, bringing the army to over 750,000 men.[28] The Air Force and Navy also grew in numbers and in budgets, to 35,000 airmen and 25,000 sailors by 1945, although for fiscal reasons Franco had to restrain attempts by both services to undertake dramatic expansions.[28] The army maintained a strength of about 400,000 men until the end of the war.[29]

Colonial empire and decolonization

Spain attempted to retain control of the last remnants of its colonial empire throughout Franco's rule. During the Algerian War (1954–62), Madrid became the base of the Organisation de l'armée secrète (OAS) right-wing French Army group which sought to preserve French Algeria. Despite this, Franco was forced to make some concessions. Henceforth, when French Morocco became independent in 1956, he surrendered Spanish Morocco to Mohammed V, retaining only a few enclaves (the Plazas de soberanía). The year after, Mohammed V invaded Spanish Sahara during the Ifni War (known as the "Forgotten War" in Spain). Only in 1975, with the Green March and the military occupation, did Morocco take control of all of the former Spanish territories in the Sahara.

In 1968, under United Nations pressure, Franco granted Spain's colony of Equatorial Guinea its independence, and the next year, ceded the exclave of Ifni to Morocco. Under Franco, Spain also pursued a campaign to gain sovereignty of the British overseas territory of Gibraltar, and closed its border with Gibraltar in 1969. The border would not be fully reopened until 1985.

Francoism

| Part of a series on |

| Falangism |

|---|

|

|

Literature

|

|

Related topics |

| Politics portal |

The consistent points in Francoism included above all authoritarianism, nationalism, National Catholicism, militarism, conservatism, anti-communism and anti-liberalism, as well as a frontal rejection of Freemasonry; some authors also quote integralism.[30][31] Stanley Payne, a scholar of fascism and Spain, notes: "scarcely any of the serious historians and analysts of Franco consider the generalissimo to be a core fascist."[32][33] According to historian Walter Laqueur "during the civil war, Spanish fascists were forced to subordinate their activities to the nationalist cause. At the helm were military leaders such as General Francisco Franco, who were conservatives in all essential respects. When the civil war ended, Franco was so deeply entrenched that the Falange stood no chance; in this strongly authoritarian regime, there was no room for political opposition. The fascists became junior partners in the government and, as such, they had to accept responsibility for the regime's policy without being able to shape it substantially".[34] The United Nations Security Council in 1946 described the Franco government as 'Fascist' denying it recognition until it developed a more representative government.[35]

Development

Unlike José Antonio Primo de Rivera (founder of the Falange and executed by the Republicans during the course of the war), Franco lacked any consistent political ideology other than fierce anti-communism and anti-anarchism.

The Falange, a fascist party formed during the Republic, soon transformed itself into the framework of reference in the Movimiento Nacional. In April 1937, the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista ("Spanish Traditionalist Phalanx of the Assemblies of National-Syndicalist Offensive", FET y de las JONS) was created from the absorption of the vast majority of the Carlist traditionalists by the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista, which itself was the result of an earlier absorption of the Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista (JONS) by José Antonio Primo de Rivera's Falange Española. This party, often referred to as Falange, became the sole party during Franco's regime. However, the term "party" was generally avoided, especially after World War II, when it was commonly referred to as the "National Movement" or just as "The Movement".

Authoritarianism

The main point of those scholars who tend to consider the Spanish State to be authoritarian rather than fascist, is that the FET-JONS were relatively heterogeneous rather than being an ideological monolith.[32][36][37][38][39] After World War II, the Falange opposed free capital markets, but the ultimately prevailing technocrats, some of whom were linked with Opus Dei, eschewed syndicalist economics and favoured increased competition as a means of achieving rapid economic growth and integration with wider Europe.[40]

The Spanish State was authoritarian: non-government trade unions and all political opponents across the political spectrum were either suppressed or controlled by all means, including police repression. Most country towns and rural areas were patrolled by pairs of Guardia Civil, a military police for civilians, which functioned as a chief means of social control. Larger cities, and capitals, were mostly under the heavily armed Policía Armada, commonly called grises due to their grey uniforms. Franco was also the focus of a personality cult which taught that he had been sent by Divine Providence to save the country from chaos and poverty.

Members of the oppressed ranged from Catholic trade unions to communist and anarchist organisations to liberal democrats and Catalan or Basque separatists. The Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and the Unión General de Trabajadores (UGT) trade unions were outlawed, and replaced in 1940 by the corporatist Sindicato Vertical. The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) party and the Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC) were banned in 1939, while the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) went underground. University students seeking democracy revolted in the late 1960s and early 1970s, which was repressed by the grises. The Basque Nationalist Party (PNV) went into exile, and in 1959, the armed separatist group ETA was created to wage a low-intensity war against Franco. Franco, like others at the time, evinced a concern about a possible Masonic and Judaic conspiracy against his regime.

Franco continued to personally sign all death warrants until just months before he died despite international campaigns requesting him to desist.

Nationalism

Franco's Spanish nationalism promoted a unitary national identity by repressing Spain's cultural diversity. Bullfighting and flamenco[41] were promoted as national traditions, while those traditions not considered Spanish were suppressed. Franco's view of Spanish tradition was somewhat artificial and arbitrary: while some regional traditions were suppressed, Flamenco, an Andalusian tradition, was considered part of a larger, national identity. All cultural activities were subject to censorship, and many were forbidden entirely, often in an erratic manner. This cultural policy relaxed over time, most notably in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Franco was reluctant to enact any form of administrative and legislative decentralisation and kept a fully centralized form of government with a similar administrative structure to that established by the House of Bourbon and General Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja. These structures were modelled after the centralised French state. As a result of this type of governance, government attention and initiatives were irregular, and often depended more on the goodwill of government representatives than on regional needs. Thus, inequalities in schooling, health care or transport facilities among regions were patent: historically affluent regions like Madrid, Catalonia, or the Basque Country fared much better than others such as Extremadura, Galicia or Andalusia.

Franco eliminated the autonomy granted by the Second Spanish Republic to the regions, and abolished the centuries-old fiscal privileges and autonomy (the fueros) in two of the three Basque provinces: Guipuzcoa and Biscay, which were officially classified as "traitor regions". The fueros were kept in the third Basque province, Alava, and also in Navarre, a former kingdom during the Middle Ages and the cradle of the Carlists, possibly due to the region's support during the civil war.

Franco also used language politics in an attempt to establish national homogeneity. Despite Franco himself being Galician, the government revoked the official statute and recognition for the Basque, Galician, and Catalan languages that the Second Spanish Republic had granted them for the first time in the history of Spain. The former policy of promoting Spanish as the only official language of the State and education was resumed, even though millions of the country's citizens spoke other languages. The legal usage of languages other than Spanish was forbidden: all government, notarial, legal and commercial documents were to be drawn up exclusively in Spanish, and any written in other languages were deemed null and void. The use of any other language was forbidden in schools, advertising, religious ceremonies and on road and shop signs. Publications in other languages were generally forbidden, though citizens continued to use them privately.

During the late 1960s, these policies became more lenient, yet non-Castilian languages continued to be discouraged and did not receive official status or legal recognition.

Additionally, the popularisation of the compulsory national educational system and the development of modern mass media, both controlled by the state and exclusively in Spanish, heavily reduced the number of speakers of Basque, Catalan and Galician. A similar trend effected other European minority languages without official protection in the second half of the 20th century, such as Scottish Gaelic in the United Kingdom or Breton in France. By the 1970s, the majority of Spain's urban population could not speak the regional minority language or even, as in some Catalan towns, its use had been abandoned altogether.

Catholicism

Although Franco himself was previously known for not being very devout,[42] his regime often used religion as a means to increase its popularity throughout the Catholic world, especially after World War II. Franco himself was increasingly portrayed as a fervent Catholic and a staunch defender of Catholicism, the declared state religion. The regime favoured very conservative Roman Catholicism, and it reversed the secularization process that had taken place under the Second Republic. According to historian Julian Casanova, 'the symbiosis of religion, fatherland and Caudillo' saw the Church assume great political responsibilities, 'a hegemony and monopoly beyond its wildest dreams' and it played 'a central role in policing the country's citizens.'[43]

The Law of Political Responsibility of February 1939 turned the Church into an extralegal body of investigation, as parishes were granted policing powers equal to those of local government officials and leaders of the falange. Some official jobs required a "good behavior" statement by a priest. According to historian Julian Casanova, "The reports that have survived reveal a clergy that was bitter because of the violent anti-clericalism and the unacceptable level of secularization that Spanish society had reached during the republican years" and the law of 1939 made the priests investigators of peoples' ideological and political pasts.[44]

The authorities encouraged denouncements in the workplace. For example, Barcelona's city hall obliged all government functionaries to "tell the proper authorities who the leftists are in your department and everything you know about their activities." A law passed in 1939 institutionalized the purging of public offices.[45] The poet Carlos Barral recorded that in his family "any allusion to Republican relatives was scrupulously avoided; everyone took part in the enthusiasm for the new era and wrapped themselves in the folds of religiosity." Only through silence could people associated with the Republic be relatively safe from imprisonment or unemployment. After the death of Franco, the 'price' of the peaceful transition to democracy would be silence and 'the tacit agreement to forget the past,'[46] which was given legal status by the 1977 Pact of forgetting.

Civil marriages that had taken place in Republican Spain were declared null and void unless they had been validated by the Church, along with divorces. Divorce, contraception, and abortions were forbidden,[47] yet enforcement was inconsistent. Children had to be given 'Christian' names. Franco was made a member of the Supreme Order of Christ by Pope Pius XII whilst Spain itself was consecrated to the Sacred Heart.[48]

The Catholic Church's ties with the Franco dictatorship gave it control over the country's schools. Crucifixes were once again placed in schoolrooms. After the war, Franco chose José Ibáñez Martín, a member of the National Catholic Association of Propagandists (AcNdP) to lead the Ministry of Education. He held the post for 12 years, during which he finished the task of purging the ministry begun by the Commission of Culture and Teaching headed by José María Pemán. Pemán led the work of Catholicizing state-sponsored schools and allocating generous funding to the Church's schools.[49] Romualdo de Toledo, head of the National Service of Primary Education was a traditionalist who described the model school as "the monastery founded by St Benedict." The clergy in charge of the education system sanctioned and sacked thousands of teachers of the progressive left and divided Spain's schools up among the families of falangists, loyalist soldiers, and Catholic families. In some provinces, like Lugo, " practically all the teachers were dismissed. This process also effected tertiary education, as Ibáñez Martín, Catholic propagandists, and the Opus Dei ensured professorships were offered only to the most faithful.[50]

The orphaned children of "Reds" were taught, in orphanages run by priests and nuns, that "their parents had committed great sins that they could help expiate, for which many were incited to serve the Church."[51]

Francoism professed a strong devotion to militarism, hypermasculinity and the traditional role of women in society. A woman was to be loving to her parents and brothers, faithful to her husband, and to reside with her family. Official propaganda confined women's roles to family care and motherhood. Most progressive laws passed by the Second Republic were declared void. Women could not become judges, or testify in trial. They could not become university professors. In the 1960s and 1970s, there was increasing liberalization, yet such measures would continue until Franco's death.

In 1947, Franco proclaimed Spain a monarchy, through the Ley de Sucesión en la Jefatura del Estado act, but did not designate a monarch. He had no particular desire for a king because of his strained relations with the Legitimist heir to the Crown, Don Juan de Borbón. Therefore, he left the throne vacant with himself as regent, and set the basis for his succession. This gesture was largely done to appease monarchist factions within the Movimiento. At the same time, Franco wore the uniform of a captain general (a rank traditionally reserved for the King), resided in the royal Pardo Palace, appropriated the kingly privilege of walking beneath a canopy, and his portrait appeared on most Spanish coins. Indeed, although his formal titles were Jefe del Estado (Head of State) and Generalísimo de los Ejércitos Españoles (Generalissimo of the Spanish Armed Forces), he was referred to as Caudillo de España por la gracia de Dios, (by the Grace of God, the Leader of Spain). Por la Gracia de Dios is a technical, legal formulation which states sovereign dignity in absolute monarchies and had been used only by monarchs before.

The long-delayed selection of Juan Carlos de Borbón as Franco's official successor in 1969 was an unpleasant surprise for many interested parties, as Juan Carlos was the rightful heir for neither the Carlists nor the Legitimists.

Narrative of the Civil War

For nearly twenty years after the war Francoist Spain presented the conflict as a crusade against Bolshevism in defense of Christian civilization. In Francoist narrative, authoritarianism had defeated anarchy and overseen the elimination of "agitators", those without God and the Judeo-Masonic conspiracy. Since Franco had relied on thousands of North African soldiers, anti-Islamic sentiment "was played down but the centuries old myth of the Moorish threat lay at the base of the construction of the 'Communist menace' as a modern-day Eastern plague."[52] The official position was therefore that the wartime Republic was simply a proto-Stalinist monolith, its leaders intent on creating a Spanish Soviet satellite. The anti-Communist crusade narrative still exists both as "a minority academic history" and in media friendly, politically oriented productions. (Stanley Payne/Pio Moa). This discourse obscured the social roots of the war and analysis of its origins. Many Spanish children grew up believing the war was fought against foreigners; the painter Julian Grau Santos has said "it was instilled in me and I always believed that Spain had won the war against foreign enemies of our historic greatness."

Economic policy

The Civil War had ravaged the Spanish economy. Infrastructure had been damaged, workers killed, and daily business severely hampered. For more than a decade after Franco's victory, the economy improved little. Franco initially pursued a policy of autarky, cutting off almost all international trade. The policy had devastating effects, and the economy stagnated. Only black marketeers could enjoy an evident affluence. Estimates of up to 200,000 people died of starvation during the early years of Francoism, a period known as Los Años de Hambre (the Years of Hunger).[53]

In 1940, the "Vertical Trade Union" was created; it was inspired by the ideas of José Antonio Primo de Rivera, who thought that class struggle would be ended by grouping together workers and owners according to corporative principles. It was the only legal trade union, and was under government control. Other trade unions were forbidden and strongly repressed along with political parties outside the FET-JONS.

On the brink of bankruptcy, a combination of pressure from the USA, the IMF and technocrats from Opus Dei managed to "convince" the regime to adopt a free market economy in 1959 in what amounted to a mini coup d'état which removed the old guard in charge of the economy, despite the opposition of Franco. This economic liberalisation was not, however, accompanied by political reforms and repression continued unabated.

Economic growth picked up after 1959 after Franco took authority away from these ideologues and gave more power to the liberal technocrats. The country implemented several development policies and growth took off creating the "Spanish Miracle". Concurrent with the absence of social reforms, and the economic power shift, a tide of mass emigration commenced: to European countries, and to lesser extent, to South America. Emigration helped the Régime in two ways: the country got rid of surplus population, and the emigrants supplied the country with much needed monetary remittances.

During the 1960s Spain experienced further increases in wealth. International firms established their factories in Spain: salaries were low, taxes nearly nonexistent, strikes were forbidden, labour health or real state regulations were unheard of, and Spain was virtually a virgin market. Spain became the second fastest-growing economy in the world, just behind Japan. The rapid development of this period became known as the Spanish Miracle. At the time of Franco's death, Spain still lagged behind most of Western Europe, but the gap between its GDP per capita and that of the major Western European economies had greatly narrowed; in world terms, Spain was already enjoying a fairly high material standard of living with basic but comprehensive services. However, the period between the mid-1970s and mid-1980s was to prove difficult as, in addition to the oil shocks to which Spain was highly exposed, the settling of the new political order took priority over the modernising of the economy.

Legacy

.jpg)

In Spain and abroad, the legacy of Franco remains controversial. In Germany a squadron named after Werner Mölders has been renamed, because as a pilot he led the escorting units in the bombing of Guernica. As recently as 2006, the BBC reported that Maciej Giertych, an MEP of the right-wing League of Polish Families, had expressed admiration for Franco's stature who allegedly "guaranteed the maintenance of traditional values in Europe."[54]

Spanish opinion has changed. Several statues of Franco and other public Francoist symbols have been removed, with the last statue in Madrid coming down in 2005.[55] Additionally, the Permanent Commission of the European Parliament "firmly" condemned in a resolution unanimously adopted in March 2006 the "multiple and serious violations" of human rights committed in Spain under the Francoist regime from 1939 to 1975.[56][57] The resolution was at the initiative of the MEP Leo Brincat and of the historian Luis María de Puig, and is the first international official condemnation of the repression enacted by Franco's regime.[56] The resolution also urged to provide public access to historians (professional and amateurs) to the various archives of the Francoist regime, including those of the Fundación Francisco Franco which, as well as other Francoist archives, remain as of 2006 inaccessible to the public.[56] Furthermore, it urged the Spanish authorities to set up an underground exhibition in the Valle de los Caídos monument, in order to explain the terrible conditions in which it was built.[56] Finally, it proposes the construction of monuments to commemorate Franco's victims in Madrid and other important cities.[56]

In Spain, a commission to repair the dignity and restitute the memory of the victims of Francoism (Comisión para reparar la dignidad y restituir la memoria de las víctimas del franquismo) was approved in the summer of 2004, and was directed by the then-vice-president María Teresa Fernández de la Vega.[56] Because of his language policies, Franco's legacy is still particularly poorly perceived in Catalonia and the Basque Provinces . The Basque Provinces and Catalonia were among the regions that offered the strongest resistance to Franco in the Civil War, as well as during his regime.

In 2008, the Association for the Recovery of Historical Memory (ARHM) initiated a systematic search for mass graves of people executed during Franco's regime, which has been supported since the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party's victory during the 2004 elections by José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero's government. A Ley de la memoria histórica de España (Law on the Historical Memory of Spain) was passed in 2007.[58] The law is supposed to enforce an official recognition of the crimes committed against civilians during the Francoist rule and organize under state supervision the search for mass graves.

Investigations have begun into wide-scale child abduction during the Franco years. The lost children of Francoism may reach 300,000.[59][60]

Flags and heraldry

Flags

At the conclusion of the Spanish Civil War, and in spite of the army's reorganisation, several sections of the army continued with their bi-colour flags improvised in 1936, but since 1940 new ensigns began to be distributed, whose main innovation was the addition of the eagle of John the Evangelist to the shield. The new arms were allegedly inspired in the coat of arms the Catholic Monarchs adopted after the taking of Granada from the Moors, but replacing the arms of Sicily with those of Navarre and adding the Pillars of Hercules on either side of the coat of arms. In 1938 the columns were placed outside the wings. On July 26, 1945 the commander's ensigns were suppressed by decree, and on October 11, a detailed regulation of flags was published that fixed the model of the bi-colour flag in use, but better defined its details, emphasising a greater style of the Saint John's eagle. The models established by this decree remained in force until 1977.

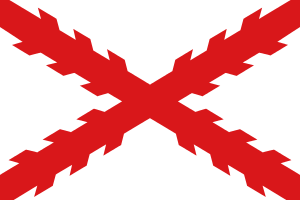

During this period two more flags were usually displayed along with the national flag: the flag of Spanish Falange (three vertical strips, red, black and red, with the black stripe wider than the red, and the yoke and arrows emblem in red in the centre of the black stripe) and the Carlist flag (the Saint Andrew saltire or Cross of Burgundy red on white), representing the National Movement which had unified Falange and the Requetés under the name Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS.

From the death of Franco in 1975 until 1977, the national flag followed the 1945 regulations. On 21 January 1977 a new regulation was approved that stipulated an eagle with more open wings, ("pasmada" eagle), with the restored Pillars of Hercules placed within the wings, and the tape with the motto UNA, GRANDE Y LIBRE (ONE, GREAT and FREE) moved over the eagle's head from its previous position around the neck.

State flag (1936–1938)

State flag (1936–1938).svg.png) State flag (1938–1945)

State flag (1938–1945).svg.png) State flag (1945–1977)

State flag (1945–1977).svg.png) State flag (1977–1981)

State flag (1977–1981) Flag of the Falange Movement

Flag of the Falange Movement Flag of the Traditionalist Movement

Flag of the Traditionalist Movement

Standards

From 1940 to 1975, Franco used the Castilian Bend (like the version of Charles I) as Head of State's Standard and Guidon: The Bend between the Pillars of Hercules, crowned with an imperial crown and open (old) royal crown.

Juan Carlos I, as Prince of Spain from 1969 to 1975, used a royal standard which was virtually identical to the one later adopted when he became King in 1975. The earlier standard differed only that it featured the royal crown of a Crown Prince, the King's royal crown has 8 arches of which 5 are visible, while the Prince's one has only 4 arches of which 3 are visible. The Royal Standard of Spain consists of a dark blue square with the Coat of arms of the King in the centre. The King's Guidon is identical to the standard, differing it in that it incorporates a fringe.

.svg.png) Standard of Francisco Franco (1940–1975)

Standard of Francisco Franco (1940–1975) Royal Standard of the Prince of Spain (1969–1975)

Royal Standard of the Prince of Spain (1969–1975)

Coat of arms

In 1938, Franco adopted a variant of the Coat of Arms reinstating some elements originally used by the House of Trastámara such as Saint John's eagle and the yoke and bundle, as follows: Quarterly, 1 and 4. quarterly Castile and León, 2 and 3. per pale Aragon and Navarra, enté en point of Granada. The arms are crowned with an open royal crown, placed on eagle displayed sable, surrounded with the pillars of Hercules, the yoke and the bundle of arrows of the Catholic Monarchs.

Coat of arms of Francisco Franco (1940–1975)

Coat of arms of Francisco Franco (1940–1975) Coat of arms of the Prince of Spain (1969–1975)

Coat of arms of the Prince of Spain (1969–1975)-Flag_Variant.svg.png) Coat of arms (1936–1938)

Coat of arms (1936–1938).svg.png) Coat of arms (1938–1945)

Coat of arms (1938–1945).svg.png) Coat of arms (1945–1977)

Coat of arms (1945–1977).svg.png) Coat of arms (1977–1981)

Coat of arms (1977–1981)

See also

- Art and culture in Francoist Spain

- Catalan State

- Francoist concentration camps

- Instituto Nacional de Colonización

- Language policies of Francoist Spain

- List of people executed by Francoist Spain

- Nationalist Foreign Volunteers

- Pact of forgetting

- Politics of Spain

- Red Terror (Spain)

- White Terror (Spain)

References

- ↑ (Spanish) "Resumen general de la población de España en 31 de Diciembre de 1940." INE. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ (Spanish) "Resumen general de la población de España en 31 de Diciembre de 1940." INE. Retrieved 11 October 2014.

- ↑ MI6 spent $200m bribing Spaniards in second world war, The Guardian

- ↑ Esparza, José Javier (2011). Juicio a Franco (1. ed.). Madrid: Libroslibres. ISBN 9788492654697.

- ↑ Helen Graham, The Spanish Civil War: A Short Introduction (2005), p. 21

- ↑ Graham (2005), p. 24

- ↑ Indalecio Prieto, Palabras al viento, 2nd edn (Mexico City: Ediciones Oasis, 1969) pp. 247–8

- ↑ Eduardo González Calleja, "La violencia y sus discursos: los límites de la 'fascistización' de la derecha española durante el régimen de la II República", in Ayer. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, No. 71, 2008, pp. 89–90

- ↑ Eduardo González Calleja, 'Aproximación a las subculturas violentas de las derechas españolas antirrepublicanas españolas (1931– 1936)', Pasado y Memoria. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, No. 2, 2003, pp. 107–42

- ↑ Eduardo González Calleja, "The symbolism of violence during the Second Republic in Spain, 1931–1936", in Chris Ealham and Michael Richards, eds, The Splintering of Spain: Cultural History and the Spanish Civil War, 1936– 1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005) pp. 23–44, 227–30

- ↑ Paul Preston, The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in 20th century Spain (2012), p. 295

- ↑ Pablo de Azcárate, Mi embajada en Londres durante la guerra civil española (Barcelona: Ariel, 1976) pp. 26–7

- ↑ Winston S. Churchill, Step by Step (London: Odhams Press, 1939) pp. 54–7.

- ↑ Dominic Tierney (11 June 2007). FDR and the Spanish Civil War: Neutrality and Commitment in the Struggle that Divided America. Duke University Press. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-8223-4055-3. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- ↑ Paul Preston, Chapter 6 "The Making of a Caudillo" in Franco: A Biography (1993), pp. 171–198

- ↑ Preston (1993), Chapter 10. "The Making of a Dictator: Franco and the Unification April 1937", p. 248–274

- ↑ Peter Anderson, "Singling Out Victims: Denunciation and Collusion in the Post-Civil War Francoist Repression in Spain, 1939–1945" in European History Quarterly Vol. 39(1), p. 7–26

- ↑ Ángela Cenarro Lagunas, "HISTORIA Y MEMORIA DEL AUXILIO SOCIAL DE FALANGE" in Pliegos de Juste 11-12 (2010), p. 71–4

- ↑ Helen Graham, "The memory of murder: mass killing, incarceration and the making of Francoism" in War Memories, Memory Wars. Political Violence in Twentieth-Century Spain

- ↑ Franco's description: "The work of pacification and moral redemption must necessarily be undertaken slowly and methodically, otherwise military occupation will serve no purpose". Roberto Cantalupo, Fu la Spagna: Ambasciata presso Franco: de la guerra civil, Madrid, 1999: pp. 206–8.

- ↑ Alejandro Quiroga, Making Spaniards, p.58. Palgrave, 2007

- ↑ The Splintering of Spain, pp. 2–3 Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-82178-0

- ↑ See Member states of the United Nations.

- ↑ The Splintering of Spain, p.4. Cambridge University Press

- ↑ The Splintering of Spain, p.7

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ "Spain - THE FRANCO YEARS".

- 1 2 3 Bowen, Wayne H.; José E. Álvarez (2007). A Military History of Modern Spain. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 114. ISBN 978-0-275-99357-3.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. (2011). The Franco Regime, 1936–1975. University of Wisconsin Pres. p. 244. ISBN 978-0-299-11074-1.

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p 31, and Paul Preston, "The Theorists of extermination" essay in Unearthing Franco's Legacy, pp 42–67 University of Notre Dame Press ISBN 0-268-03268-8

- ↑ "Fundamentalism in Comparative Perspective".

- 1 2 Payne, Stanley Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, p. 476 1999 Univ. of Wisconsin Press

- ↑ Laqueur, Walter Fascism: Past, Present, Future, p. 13, 1997 Oxford University Press US

- ↑ Fascism: Past, Present, Future. Google Books.

- ↑ Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes, p. 316, 2006, HarperPress, ISBN 0-00-719574-5; see also United Nations Security Council Resolution 7

- ↑ De Menses, Filipe Ribeiro Franco and the Spanish Civil War, p. 87, Routledge

- ↑ Gilmour, David, The Transformation of Spain: From Franco to the Constitutional Monarchy, p. 7 1985 Quartet Books

- ↑ Payne, Stanley Fascism in Spain, 1923–1977, p. 347, 476 1999 Univ. of Wisconsin Press

- ↑ Laqueur, Walter Fascism: Past, Present, Future p. 13 1996 Oxford University Press

- ↑ "The Franco Years: Policies, Programs, and Growing Popular Unrest." A Country Study: Spain <http://lcweb2.loc.gov/frd/cs/estoc.html#es0034>

- ↑ Roman, Mar. "Spain frets over future of flamenco." 27 October 2007. Associated Press.

- ↑ Viñas, Á. (2012). En el combate por la historia: la República, la guerra civil, el franquismo.

- ↑ Julian Casanova, Professor of Contemporary History at the University of Zaragoza, The Faces of Terror, in Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p.108

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p. 108/1115

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p.103

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy p. 128–129 , Michael Richards Grand Narratives, Collective Memory, and Social History.

- ↑ http://search.boe.es/datos/imagenes/BOE/1954/198/A04862.tif

- ↑ Michael Burleigh, Sacred Causes, p. 317–318, 2006, ISBN 0-00-719574-5

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy p. 112

- ↑ Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p.113

- ↑ Ignacio Fernandez de Mata, The Rupture of the World and the Conflicts of Memory, essay in Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p. 295

- ↑ Michael Richards, Unearthing Franco's Legacy, p129

- ↑ Sánchez, Antonio Cazorla (July 2010). Fear and Progress: Ordinary Lives in Franco's Spain, 1939–1975. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 58–60. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Europe diary: Franco and Finland, BBC News, 6 July 2006 (English)

- ↑ Madrid removes last Franco statue, BBC News, 17 March 2005 (English)

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Primera condena al régimen de Franco en un recinto internacional, EFE, El Mundo, 17 March 2006 (Spanish)

- ↑ Von Martyna Czarnowska, Almunia, Joaquin: EU-Kommission (4): Ein halbes Jahr Vorsprung, Weiner Zeitung, 17 February 2005 (article in German language). Accessed 26 August 2006.

- ↑ "Bones of Contention". The Economist. 2008-09-27. Archived from the original on 2008-10-06. Retrieved 2008-10-06.

- ↑ Adler, Katya (18 October 2011). "Spain's stolen babies and the families who lived a lie". BBC News.

- ↑ Tremlett, Giles (27 January 2011). "Victims of Spanish 'stolen babies network' call for investigation". The Guardian.

Further reading

- Gerald Brenan, The Face of Spain, (Serif, London, 2010). First-hand account of travels around Spain in 1949.

- Payne, S. (1987). The Franco regime. 1st ed. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Luis Fernandez. Franco. Editorial

External links

- Text of Franco's Fundamental Laws at the Wayback Machine (archived July 2, 2007), the Spanish Constitution under Franco. (Spanish)

- Video

- Relations of Members of the United Nations with Spain

- Condecoraciones otorgadas por Francisco Franco a Benito Mussolini y a Adolf Hitler

Coordinates: 41°18′00″N 0°44′56″W / 41.300°N 0.749°W