Barunga, Northern Territory

Barunga is a small aboriginal community located approximately 80 kilometres (50 mi) southeast of Katherine, in the Northern Territory of Australia. Formerly known as Beswick, it was later called Bamyili before it was finally renamed Barunga. It is now part of the Roper Gulf Region Local Government area.

At the 2011 census, Barunga had a population of 313.[1] The community has a health clinic, camping grounds, sports oval, basketball courts, softball pitch, school, council office and a community store. Each year, the community holds the Barunga Festival which occurs in mid June.

History

Aboriginal people have lived in Barunga and the surrounding region for thousands of years.

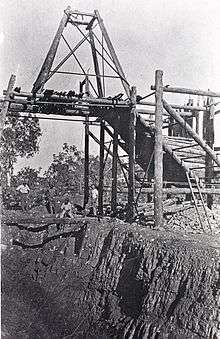

In September 1913, a goldfield named Maranboy was declared for a period of two years.[2] Maranboy was located eight kilometres from where Barunga is today.[3] Tin was discovered at Maranboy in 1918 by prospectors Scharber and Richardson.[4] Tin mines and a battery were operational in the same year.[5] Prospectors of European, Chinese and Aboriginal descent worked at Maranboy. The most notable of them was Harold Snell, who later went on to build many significant buildings in Darwin. The battery closed in 1949 for repairs but never reopened.[6] Many of the Aboriginal people who serviced the mine returned to Beswick Creek.

A Dutch Air Force Dakota (DC3) crashed landed near Beswick in 1947.[7] All passengers survived, with four crew travelling about 100 miles down the Katherine River to get help. After running out of food they killed one of two dogs they had with them.[8] The wings were eventually removed and the remains of the plane were towed to Katherine.[9]

In 1948, the community moved from Beswick to Tandangal, because of risk of flooding from recent heavy rains. An influenza epidemic spread through the community in May 1951.[10] By November it had killed seven people.[11] The community returned to Beswick a few years later, when Tandangal's creeks dried up limiting water supplies. There are also some reports that Tandangal was a sacred site, and the people were reluctant to settle there.

In early 1951, the Northern Territory Government started to develop the community, then known as the Beswick community, building basic housing infrastructure and creating some minor employment opportunities. Local farmers also employed the aboriginal people, even running a peanut farm at Beswick Creek. The farm only lasted a few years. As Beswick grew, new tribes formed a camp on the other side of the river known as 'The Compound' where the people made humpies. The elders changed the name of The Compound to Bamyili in 1965. In 1984, it changed its name to Barunga.

The Barunga school was first opened in 1954 with 42 children enrolled. Today, Barunga school educates about 65 students aged from 6 months to 19 years.[12]

Australian cycling champion Cadel Evans spent his early childhood in Barunga.[13]

Barunga Festival

Each year the remote community holds a music and cultural celebration known as the Barunga Festival. It officially began in 1985 at the instigation of the leader of the Bagala clan, Bangardi Lee. The community was then known as Bamyilli. The festival has been held every year since on the Queen’s Birthday long weekend in June and features a program of workshops, dancing ceremonies, traditional bush tucker gathering, didgeridoo making, basket weaving and musical performances and sport.[14]

The Barunga Statement

In 1988, as part of Bicentennial celebrations, Prime Minister of Australia, Bob Hawke, visited the Northern Territory for the Barunga festival where he was presented with a statement of Aboriginal political objectives by Galarrwuy Yunupingu and Wenten Rubuntja.[15] Painted on a 1.2 metre square sheet of composite wood, it became known as the ‘Barunga Statement’.[16] It stated:

We, the Indigenous owners and occupiers of Australia, call on the Australian Government and people to recognise our rights:

to self-determination and self-management, including the freedom to pursue our own economic, social, religious and cultural development;

to permanent control and enjoyment of our ancestral lands;

to compensation for the loss of use of our lands, there having been no extinction of original title;

to protection of and control of access to our sacred sites, sacred objects, artefacts, designs, knowledge and works of art;

to the return of the remains of our ancestors for burial in accordance with our traditions;

to respect for and promotion of our Aboriginal identity, including the cultural, linguistic, religious and historical aspects, and including the right to be educated in our own languages and in our own culture and history;

in accordance with the universal declaration of human rights, the international covenant on economic, social and cultural rights, the international covenant on civil and political rights, and the international convention on :the elimination of all forms of racial discrimination, rights to life, liberty, security of person, food, clothing, housing, medical care, education and employment opportunities, necessary social services and other basic rights.

We call on the Commonwealth to pass laws providing:

A national elected Aboriginal and Islander organisation to oversee Aboriginal and Islander affairs;

A national system of land rights;

A police and justice system which recognises our customary laws and frees us from discrimination and any activity which may threaten our identity or security, interfere with our freedom of expression or association, or otherwise prevent our full enjoyment and exercise of universally recognised human rights and fundamental freedoms.

We call on the Australian Government to support Aborigines in the development of an international declaration of principles for indigenous rights, leading to an international covenant.

And we call on the Commonwealth Parliament to negotiate with us a Treaty recognising our prior ownership, continued occupation and sovereignty and affirming our human rights and freedom.[1]

- ^ "Barunga Statement presented to Prime Minister Bob Hawke in 1988". australia.gov.au. Australian Government. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

Prime Minister Hawke responded by saying that he wished to conclude a treaty between Aboriginal and other Australians by 1990, but his wish was not fulfilled. Controversy erupted over the exposure of sacred material in the bark painting leading some Indigenous leaders to call for its return. Some leaders alleged the presentation of the painting resulted in at least ten deaths due to "munya", which translates as remorse in the Aboriginal system of payback.[17] In 1991, his last act as Prime Minister was to hang the Barunga Statement at Parliament House. He did so one minute before Paul Keating was sworn in as the new Prime Minister, stating "its presence here calls on those who follow me, it demands of them that they continue efforts that they find solutions to the abundant problems that still face the Aboriginal people of this country."[18]

The Australian Aboriginal band, Yothu Yindi, wrote the hit song "Treaty" to commemorate the statement. Lead singer Mandawuy Yunupingu, with his older brother Galarrwuy, wanted to highlight the lack of progress on the treaty between Aboriginal peoples and the Federal Government. Mandawuy Yunupingu said:

"Bob Hawke visited the Territory. He went to this gathering in Barunga. And this is where he made a statement that there shall be a treaty between black and white Australia. Sitting around the camp fire, trying to work out a chord to the guitar, and around that camp fire, I said, "Well, I heard it on the radio. And I saw it on the television." That should be a catchphrase. And that's where 'Treaty' was born".[19]

The song became a worldwide success.

References

- 1 2 Australian Bureau of Statistics (31 October 2012). "Barunga (State Suburb)". 2011 Census QuickStats. Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "PROCLAMATION.". Northern Territory Times And Gazette. XXXVIII, (2082). Northern Territory, Australia. 2 October 1913. p. 8. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Barunga". Roper Gulf Regional Council. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- ↑ "Maranboy Tinfield.". Northern Territory Times And Gazette. XLI, (2343). Northern Territory, Australia. 5 October 1918. p. 12. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "MINING NEWS". Northern Territory Times And Gazette. XLI, (2322). Northern Territory, Australia. 11 May 1918. p. 7. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "LIVING ON CREDIT MARANBOY BATTERY STILL CLOSED MINES DEPT. INEFFICIENCY". Northern Standard. 4, (186). Northern Territory, Australia. 16 December 1949. p. 1. Retrieved 12 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "DUTCH DAKOTA CRASHED EAST OF KATHERINE GORGE: SEARCH PARTY ON WAY". Northern Standard. 2, (14). Northern Territory, Australia. 3 April 1947. p. 7. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Crew Of Crashed Dakota Eat". Northern Standard. 2, (14). Northern Territory, Australia. 3 April 1947. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Aeroplane". Territory Stories. Northern Territory Library. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ "FEVER AMONG NATIVES". Barrier Miner. LXIII, (17,396). New South Wales, Australia. 26 February 1951. p. 11. Retrieved 12 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Mystery 'Flu Kills 7 Aborigines". Newcastle Morning Herald And Miners' Advocate (23,428). New South Wales, Australia. 3 November 1951. p. 3. Retrieved 12 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Barunga". Teaching Jobs. Northern Territory Government. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Edmund, Sam (9 July 2016). "Cadel Evans interview: I do about a quarter of the riding I used to ... about 10,000km a year now". Herald Sun. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ "About the festival and how to get there". Barunga Festival. Retrieved 10 August 2016.

- ↑ Howie-Willis, Ian (2001). "Barunga Statement". The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS). Archived from the original on 2011-07-17. Retrieved 2008-11-04.

- ↑ "Message 'very fitting' last act for Hawke". The Canberra Times. 66, (20,706). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 21 December 1991. p. 2. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Aboriginal plea on 'payback' painting". The Canberra Times. 64, (19,751). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 5 November 1989. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "Message 'very fitting' last act for Hawke". The Canberra Times. 66, (20,706). Australian Capital Territory, Australia. 21 December 1991. p. 1. Retrieved 10 August 2016 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "George Negus Tonight Profiles - Transcripts - Mandawuy Yunupingu". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC). 2004-07-08. Retrieved 2008-11-06.