Abraham ibn Ezra

Rabbi Abraham Ben Meir Ibn Ezra (Hebrew: אַבְרָהָם אִבְּן עֶזְרָא or ראב"ע, Arabic: ابن عزرا; also known as Abenezra or Aben Ezra, 1089–1167) was born in Tudela, Navarre in 1089,[1] and died c. 1167, apparently in Calahorra.[2] He was one of the most distinguished Jewish poets and philosophers of the Middle Ages.

Biography

Abraham Ibn Ezra was born in Tudela, in the present-day Spanish province of Navarre, when the town was under the Muslim rule of the emirs of Zaragoza.[3] Later he lived in Córdoba. In Granada, it is said, he met his future friend (and perhaps his father-in-law) Yehuda Halevi. He left Spain before 1140 to escape persecution of the Jews by the new fanatical regime of the Almohads. He led a life of restless wandering, which took him to North Africa, Egypt (in 1109, maybe in the company of Yehuda Halevi), the Land of Israel, Italy (Rome in 1140–1143, Lucca, Mantua, Verona), Southern France (Narbonne, Béziers), Northern France (Rouen), England (London, and Oxford in 1158), and back again to Narbonne in 1161, until his death on January 23 or 28, 1164, the exact location unknown: maybe at Calahorra at the border of Navarre and Aragon, or maybe in Rome or in the Holy Land. There is a legend that he died in England from a fever and a sickness that came upon him after an encounter with a pack of wild black dogs. This legend is attached to the belief that he denied the existence of demons.[4]

The crater Abenezra on the Moon was named in his honor.

Works

At several of the above-named places, Ibn Ezra remained for some time and developed a rich literary activity. In his native land, he had already gained the reputation of a distinguished poet and thinker but apart from his poems, his works, which were all in the Hebrew language, were written in the second period of his life. With these works, covering the first instance the field of Hebrew philology and Biblical exegesis, he fulfilled the great mission of making accessible to the Jews of Christian Europe the treasures of knowledge enshrined in the works written in Arabic that he had brought with him from Spain.

His grammatical writings, among which Moznayim ("Scales", 1140) and Zahot (Tzahot = "Dazzlings",[5] 1141) are the most valuable, were the first expositions of Hebrew grammar in the Hebrew language, in which the system of Judah Hayyuj and his school prevailed. He also translated into Hebrew the two writings of Hayyuj in which the foundations of the system were laid down.

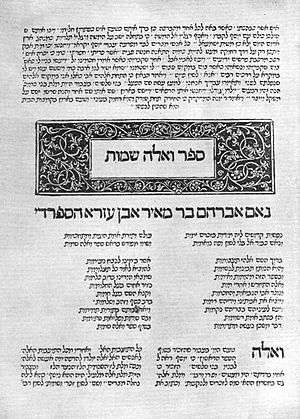

Of greater original value than the grammatical works of Ibn Ezra are his commentaries on most of the books of the Bible, of which, however, the Books of Chronicles have been lost. His reputation as an intelligent and acute expounder of the Bible was founded on his commentary on the Torah, of which the great popularity is evidenced by the numerous commentaries that were written upon it. In the editions of this commentary (editio princeps Naples 1488. See image at right), the commentary on the Book of Exodus is replaced by a second, more complete commentary of Ibn Ezra, while the first and shorter commentary on Exodus was not printed until 1840. The great editions of the Hebrew Bible with rabbinical commentaries contained also commentaries of Ibn Ezra's on the following books of the Bible: Isaiah, Minor Prophets, Psalms, Job, Torah, Daniel; the commentaries on Proverbs and Ezra–Nehemiah bearing his name are really those of Moses Kimhi. Ibn Ezra wrote a second commentary on Genesis as he had done on Exodus, but this was never finished. There are second commentaries also by him on the Song of Songs, Esther and Daniel.

Ibn Ezra also wrote a commentary on the book of Ecclesiastes. Uncharacteristically of either Ibn Ezra's other commentaries on biblical works, or of Jewish exegesis of the time, the commentary on Ecclesiastes begins with an autobiographical poem (written in the third person) relating his life experience to the material in Ecclesiastes. Although the poem states that he fled "from [my] home in Spain/Going down to Rome with heavy spirit", this does not resolve the question of what intermediate journeys Ibn Ezra may have made before settling in Rome, possibly in the company of R' Yehudah HaLevi.[6]

The importance of the exegesis of Ibn Ezra consists in the fact that it aims at arriving at the simple sense of the text, the Peshat, on grammatical principles. It is in this that, although he takes a great part of his exegetical material from his predecessors, the originality of his mind is everywhere apparent, an originality that displays itself also in the witty and lively language of his commentaries.

Influence on biblical criticism and philosophy of religion

Ibn Ezra occupies a unique role among medieval commentators in that, on the one hand, his commentary has historically been cited by mainstream Orthodoxy, but on the other hand, his reluctance to reconcile problematic Biblical passages through midrashic exegesis, even at the expense of traditional dogma, put him in opposition to his contemporaries such as Rashi and provided early support for the type of textual criticism that is now accepted by Reform and Conservative Judaism.[7] For example, in his commentary, Ibn Ezra adheres to the literal sense of the texts, avoiding Rabbinic allegories and Cabbalistic interpretations, though he remains faithful to the Jewish traditions. This does not prevent him from exercising an independent criticism that, according to some writers,[8] exhibits a marked tendency toward rationalism, to the extent that he judged other biblical commentary "against his twin standards of accuracy, grammatical precision and reliability", and in that regard "Ibn Ezra determined that, aim notwithstanding, Rashi had successfully grasped and imparted the contextual sense 'but one time in a thousand.'"[9]

Indeed, Ibn Ezra is claimed by the proponents of the higher biblical criticism of the Torah as one of its earliest pioneers. Baruch Spinoza, in concluding that Moses did not author the Torah, and that the Torah and other protocanonical books were written or redacted by somebody else, supposedly Ezra, and others centuries later, found precedent for these "heretical" views (which resulted in his cherem or excommunication from the Amsterdam Jewish community) in Ibn Ezra's commentary on Deuteronomy.[10] Specifically, in discussing Deuteronomy 1:1 ("These are the words which Moshe addressed to all Israel beyond the Jordan River"), Ibn Ezra was troubled by the anomalous nature of referring to Moses as being "beyond [i.e., on the other side] of the Jordan", as though the writer was oriented in the land of Cana'an (west of the Jordan River), although Moses and the Children of Israel had not yet crossed the Jordan at that point in the Biblical narrative.[11] Relating this inconsistency to others in the Torah, Ibn Ezra famously stated, "If you can grasp the mystery behind the following problematic passages: 1) The final twelve verses of this book [i.e., Deuteronomy 34:1–12, describing the death of Moses], 2) 'Moshe wrote [this song on the same day, and taught it to the children of Israel]' [Deuteronomy 31:22]; 3) 'At that time, the Canaanites dwelt in the land' [Genesis 12:6]; 4) '... In the mountain of God, He will appear' [Genesis 22:14]; 5) 'behold, his [Og king of Bashan] bed is a bed of iron [is it not in Rabbah of the children of Ammon?]' you will understand the truth."[11]

Spinoza concluded that Ibn Ezra's hints about "the truth", and other such hints scattered through Ibn Ezra's commentary in reference to seemingly anachronistic verses,[12] as "a clear indication that it was not Moses who wrote the Pentateuch but someone else who lived long after him, and that it was a different book that Moses wrote".[10] Spinoza and later scholars were thus able to expand on several of Ibn Ezra's hints and provide much stronger evidence for Non-Mosaic authorship.[13]

Nevertheless, some Orthodox writers have recently addressed one of Ibn Ezra's hints as being interpreted to be consistent with the Orthodox Jewish creed that the entire Torah was divinely dictated in a word-perfect manner to Moses.[14]

Ibn Ezra's commentaries, and especially some of the longer excursuses, contain numerous contributions to the philosophy of religion. One work in particular that belongs to this province, Yesod Mora ("Foundation of Awe"), on the division and the reasons for the Biblical commandments, he wrote in 1158 for a London friend, Joseph ben Jacob. In his philosophical thought neo-platonic ideas prevail; and astrology also had a place in his view of the world. He also wrote various works on mathematical and astronomical subjects, among which "three treatises on numbers which helped to bring the Indian symbols and ideas of decimal fractions to the attention of some of the learned people in Europe"[15]

In contrast his other works, the most important of which include The Book of the Secrets of the Law, The Mystery of the Form of the Letters, The Enigma of the Quiescent Letters, The Book of the Name, The Book of the Balance of the Sacred Language and The Book of Purity of the Language, demonstrate a more Cabbalistic viewpoint . They were written during his life of travel, and they reflect the unsteadiness of his outward circumstances.

Biblical commentaries

His chief work is the commentary on the Torah, which, like that of Rashi, has called forth a host of super-commentaries, and which has done more than any other work to establish his reputation. It is extant both in numerous manuscripts and in printed editions. The commentary on Exodus published in the printed editions is a work by itself, which he finished in 1153 in southern France.

The complete commentary on the Torah, which, as has already been mentioned, was finished by Ibn Ezra shortly before his death, was called Sefer ha-Yashar ("Book of the Straight").

In the rabbinical editions of the Bible the following commentaries of Ibn Ezra on Biblical books are likewise printed: Isaiah; the Twelve Minor Prophets; Psalms; Job; the Megillot; Daniel. The commentaries on Proverbs and Ezra-Nehemiah bearing Ibn Ezra's name are by Moses Kimhi. Another commentary on Proverbs, published in 1881 by Driver and in 1884 by Horowitz, is also erroneously ascribed to Ibn Ezra. Additional commentaries by Ibn Ezra to the following books are extant: Song of Solomon; Esther; Daniel. He also probably wrote commentaries to a part of the remaining books, as may be concluded from his own references..

Hebrew grammar

- Moznayim (1140), chiefly an explanation of the terms used in Hebrew grammar; as early as 1148 it was incorporated by Judah Hadassi in his Eshkol ha-Kofer, with no mention of Ibn Ezra (see Monatsschrift, xl. 74), first ed. in 1546. The most recent edition is Sefer Moznayim. Introducción (en castellano e inglés). Edición crítica del texto hebreo y versión castellana de Lorenzo Jiménez Patón, revisada, completada y reelaborada por Angel Sáenz-Badillos. Córdoba: Ediciones el Almendro, 2002.

- Translation of the work of Hayyuj into Hebrew (ed. Onken, 1844).

- Sefer ha-Yesod, or Yesod Diqduq, (see Bacher, Abraham ibn Ezra als Grammatiker, pp. 8–17). It has been published by N. Allony: Yesod Diqduq. Jerusalem: Mossad Ha-rav Kook, 1984.

- Tzakhot (1145), on linguistic correctness, his best grammatical work, which also contains a brief outline of modern Hebrew meter; first ed. 1546. There is a critical edition by C. del Valle: Sefer Sahot. Salamanca: Univ. Pontificia de Salamanca, 1977.

- Safah Berurah (see above), first ed. 1830. A critical edition has been recently published: Śafah bĕrurah. La lengua escogida. Introducción (en castellano e inglés). Edición crítica del texto hebreo y versión castellana de Enrique Ruiz González, revisada, completada y reelaborada por Angel Sáenz-Badillos. Córdoba: Ediciones el Almendro, 2004.

- A short outline of grammar at the beginning of the unfinished commentary on Genesis. The importance of Ibn Ezra's grammatical writings has already been treated in Grammar, Hebrew.

- A defence of Saadyah Gaon against Adonim's criticisms: Sefer Haganah 'al R. Sa'adyah Gaon. Ed. I. Osri, Bar-Ilan University, 1988.

Smaller works – partly grammatical, partly exegetical

- Sefat Yeter, in defense of Saadia Gaon against Dunash ben Labrat, whose criticism of Saadia, Ibn Ezra had brought with him from Egypt; published by Bislichs 1838 and Lippmann 1843.

- Sefer ha-Shem, ed. Lippmann, 1834.

- Yesod Mispar, a small monograph on numerals, ed. Pinsker, 1863, at the end of his book on the Babylonian-Hebrew system of punctuation.

- Iggeret Shabbat, a responsum on the Sabbath, dated 1158, ed. Luzzatto, in "Kerem Hemed", iv. 158 et seq.

Religious philosophy

- Yesod Mora Vesod Hatorah (1158), on the division of and reasons for the Biblical commandments; 1st ed. 1529.

Mathematics and astronomy

- Sefer ha-Ekhad, on the peculiarities of the numbers 1–9.

- Sefer ha-Mispar or Yesod Mispar, arithmetic.

- Luchot, astronomical tables.

- Sefer ha-'Ibbur, on the calendar (ed. Halberstam, 1874).

- Keli ha-Nechoshet, on the astrolabe (ed. Edelmann, 1845).

- Shalosh She'elot, in answer to three chronological questions of David Narboni.

Astrology

Ibn Ezra composed his first book on astrology in Italy, before his move to France:

- Mishpetai ha-Mazzelot ("Judgments of the Zodiacal Signs"), on the general principles of astrology

In seven books written in Béziers in 1147–1148 Ibn Ezra then composed a systematic presentation of astrology, starting with an introduction and a book on general principles, and then five books on particular branches of the subject. The presentation appears to have been planned as an integrated whole, with cross-references throughout, including references to subsequent books in the future tense. Each of the books is known in two versions, so it seems that at some point Ibn Ezra also created a revised edition of the series.[16]

- Reshit Hokhma ("The Beginning of Wisdom"), an introduction to astrology, perhaps a revision of his earlier book (tr. 1998, M. Epstein)

- Sefer ha-Te'amim ("Book of Reasons"), an overview of Arabic astrology, giving explanations for the material in the previous book. (tr. 1994, M. Epstein)

- Sefer ha-Moladot ("Book of Nativities"), on astrology based on the time and place of birth

- Sefer ha-Me'orot ("Book of Luminaries" or "Book of Lights"), on medical astrology

- Sefer ha-She'elot ("Book of Interrogations"), on questions about particular events

- Sefer ha-Mivharim ("Book of Elections", also known as "Critical Days"), on optimum days for particular activities

- Sefer ha-Olam ("Book of the World"), on the fates of countries and wars, and other larger-scale issues

- Translation of two works by the astrologer Mashallah ibn Athari: "She'elot" and "Qadrut" (Steinschneider, "Hebr. Uebers." pp. 600–603).

- Sela, Shlomo, ed./trans. Abraham Ibn Ezra: The Book of Reasons. A Parallel Hebrew-English Critical Edition of the Two Versions of the Text. Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Poetry

There are a great many other poems by Ibn Ezra, some of them religious (the editor of the "Diwan" in an appended list mentions nearly 200 numbers) and some secular – about love, friendship, wine, didactic or satirical. Like his friend Yehuda Halevi, he used the Arabic poetic form of Muwashshah.

Legacy

Robert Browning's poem Rabbi Ben Ezra, beginning "Grow old along with me/The best is yet to be", a meditation on ibn Ezra's life and work, appeared in Browning's Dramatis Personae,[17] in 1864. In turn, Rabbi Ben Ezra has been used in various ways:

- Isaac Asimov's short novel "Grow Old with Me"[18] was expanded into the novel Pebble in the Sky,[19] which quotes Rabbi Ben Ezra.

- The second line of Rabbi Ben Ezra, "The Best Is Yet to Be", is the Motto of the Anglo-Chinese Schools in Singapore and Jakarta.

- John Lennon adapts part of Rabbi Ben Ezra in "Grow Old with Me".[20]

- Browning's poem "Rabbi Ben Ezra" is also cited in The Twilight Zone episode "The Trade-Ins"

See also

- Rabbinic literature

- List of rabbis

- Jewish views of astrology

- Jewish commentaries on the Bible

- Kabbalistic astrology

- Astrology in Judaism

- Hebrew astronomy

- Islamic astrology

References

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Judaica, pages 1163–1164

- ↑ Jewish Encyclopedia (online); Chambers Biographical Dictionary gives the dates 1092/93 – 1167

- ↑ It has been a common error to publish that he was born in Toledo, Spain; however this is due to an incorrect reading of Hebrew written documents.

- ↑ Joshua Trachtenberg, Jewish Magic and Superstition www.sacred-texts.com chapter 3, pp. 26–27

- ↑ BDB Lexicon, page 850

- ↑ Jewishencyclopedia.com, entry for Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ben Meir http://jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/7985-ibn-ezra-abraham-ben-meir-aben-ezra

- ↑ Ben Elton, Revelation, Tradition, and Scholarship: A Response (available at http://thinkjudaism.wordpress.com/tag/conservative-judaism/)

- ↑ see introduction to Yam Shel Shlomo by Rabbi Shlomo Luria

- ↑ Eric Lawee, "Words Unfitly Spoken: Late Medieval Criticism of the Role of Midrash in Rashi's Commentary on the Torah", in Between Rashi and Maimonides: Themes in Medieval Jewish Law, Thought and Culture (ed. Ephraim Kanarfogel) (see excerpt at http://www.rationalistjudaism.com/2012/03/anti-rationalism-and-rashi.html).

- 1 2 http://www.sacred-texts.com/phi/spinoza/treat/tpt12.htm

- 1 2 Jay F. Schachter, The Commentary of Abraham Ibn Ezra on the Pentateuch: Volume 5, Deuteronomy (KTAV Publishing House 2003) (available at https://books.google.com/books?id=XODZ7yo2iqgC&printsec=frontcover&dq=ibn+ezra+deuteronomy&hl=en&sa=X&ei=QHkOUuXIC4OqyAGUkoAw&ved=0CC0Q6AEwAA#v=snippet&q=reveal&f=false)

- ↑ For example, Spinoza understood Ibn Ezra's commentary on Genesis 12:6 ("And the Canaanite was then in the land"), wherein Ibn Ezra esoterically stated that "some mystery lies here, and let him who understands it keep silent," as proof that Ibn Ezra recognized that at least certain Biblical passages had been inserted long after the time of Moses.

- ↑ See for example, "Who wrote the Bible" and the "Bible with Sources Revealed" both by Richard Elliott Friedman

- ↑ postings from November 24–25, 2009

- ↑ J. J. O'Connor; E. F. Robertson. "Abraham ben Meir ibn Ezra".

- ↑ Shlomo Sela (2000), "Encyclopedic aspects of Ibn Ezra's scientific corpus", in Steven Harvey (ed), The Medieval Hebrew Encyclopedias of Science and Philosophy: Proceedings of the Bar-Ilan University Conference, Springer. ISBN 0-7923-6242-X. See pp. 158 et seq.

- ↑ Robert Browning (1864/1969), Dramatis Personae, reprint, London: Collins.

- ↑ "Grow Old with Me" (1947), in Isaac Asimov (1986), The Alternate Asimovs, Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- ↑ Isaac Asimov (1950), Pebble in the Sky, Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- ↑ "Grow Old with Me", on John Lennon (1980/1984) Milk and Honey, Polydor.

Further reading

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Singer, Isidore; et al., eds. (1901–1906). "article name needed". Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. - Carmi, T. (ed.), The Penguin book of Hebrew verse, Penguin Classics, 2006, London ISBN 978-0-14-042467-6

- Charlap, Luba. 2001. Another view of Rabbi Abraham Ibn-Ezra's contribution to medieval Hebrew grammar. Hebrew Studies 42:67-80.

- Epstein, Meira, "Rabbi Avraham Ibn Ezra" – An article by Meira Epstein, detailing all of ibn Ezra's extant astrological works

- Glick, Thomas F.; Livesey, Steven John; and Wallis, Faith, Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia, Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0-415-96930-1. Cf. pp. 247–250.

- Goodman, Mordechai S. (Translator), The Sabbath Epistle of Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra,('iggeret hashabbat). Ktav Publishing House, Inc., New Jersey (2009). ISBN 978-1-60280-111-0

- Halbronn, Jacques, Le monde juif et l'astrologie, Ed Arché, Milan, 1985

- Halbronn, Jacques, Le livre des fondements astrologiques, précédé du Commencement de la Sapience des Signes, Pref. G. Vajda, Paris, ed Retz 1977

- Holden, James H., History of Horoscopic Astrology, American Federation of Astrologers, 2006. ISBN 0-86690-463-8. Cf. pp. 132–135.

- Jewish Virtual Library, Abraham Ibn Ezra

- Johansson, Nadja, Religion and Science in Abraham Ibn Ezra's Sefer Ha-Olam (Including an English Translation of the Hebrew Text)

- Langermann, Tzvi, "Abraham Ibn Ezra", Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, 2006. Accessed June 21, 2011.

- Levine, Etan. Ed., Abraham ibn Ezra's Commentary to the Pentateuch, Vatican Manuscript Vat. Ebr. 38. Jerusalem: Makor, 1974.

- Sela, Shlomo, "Abraham Ibn Ezra's Scientific Corpus Basic Constituents and General Characterization", in Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, (2001), 11:1:91–149 Cambridge University Press

- Sela, Shlomo, Abraham Ibn Ezra and the Rise of Medieval Hebrew Science, Brill, 2003. ISBN 90-04-12973-1

- Siegel, Eliezer, Rabbi Abraham Ibn Ezra's Commentary to the Torah

- skyscript.co.uk, 120 Aphorisms for Astrologers by Abraham ibn Ezra

- skyscript.co.uk, Skyscript: The Life and Work of Abraham Ibn Ezra

- Smithuis, Renate, "Abraham Ibn Ezra's Astrological Works in Hebrew and Latin: New Discoveries and Exhaustive Listing", in Aleph (Aleph: Historical Studies in Science and Judaism), 2006, No. 6, Pages 239-338

- Wacks, David. "The Poet, the Rabbi, and the Song: Abraham ibn Ezra and the Song of Songs". Wine, Women, and Song: Hebrew and Arabic Literature in Medieval Iberia. Eds. Michelle M. Hamilton, Sarah J. Portnoy and David A. Wacks. Newark, Del.: Juan de la Cuesta Hispanic Monographs, 2004. 47–58.

- Walfish, Barry, "The Two Commentaries of Abraham Ibn Ezra on the Book of Esther", The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 79, No. 4 (April 1989), pp. 323–343, University of Pennsylvania Press

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Rudavsky, Tamar M. (2007). "Ibn ʿEzra: Abraham ibn ʿEzra". In Thomas Hockey; et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 553–5. ISBN 978-0-387-31022-0. (PDF version)

- Levey, Martin (2008) [1970-80]. "Ibn Ezra, Abraham Ben Meir". Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com. External link in

|=(help) - Roth, Norman. Abraham Ibn Ezra — Highlights of His Life. External link in

|title=(help)