Zika virus

| Zika virus | |

|---|---|

| |

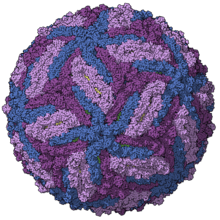

| Electron micrograph of the virus. Virus particles (digitally colored purple) are 40 nm in diameter, with an outer envelope and a dense inner core.[1] | |

| |

| Zika virus envelope model, colored by chains, PDB entry 5ire.[2] | |

| Virus classification | |

| Group: | Group IV ((+)ssRNA) |

| Family: | Flaviviridae |

| Genus: | Flavivirus |

| Species: | Zika virus |

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a member of the virus family Flaviviridae.[3] It is spread by daytime-active Aedes mosquitoes, such as A. aegypti and A. albopictus.[3] Its name comes from the Zika Forest of Uganda, where the virus was first isolated in 1947.[4] Zika virus is related to the dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile viruses.[4] Since the 1950s, it has been known to occur within a narrow equatorial belt from Africa to Asia. From 2007 to 2016, the virus spread eastward, across the Pacific Ocean to the Americas, leading to the 2015–16 Zika virus epidemic.

The infection, known as Zika fever or Zika virus disease, often causes no or only mild symptoms, similar to a very mild form of dengue fever.[3] While there is no specific treatment, paracetamol (acetaminophen) and rest may help with the symptoms.[5] As of 2016, the illness cannot be prevented by medications or vaccines.[5] Zika can also spread from a pregnant woman to her fetus. This can result in microcephaly, severe brain malformations, and other birth defects.[6][7] Zika infections in adults may result rarely in Guillain–Barré syndrome.[8]

In January 2016, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued travel guidance on affected countries, including the use of enhanced precautions, and guidelines for pregnant women including considering postponing travel.[9][10] Other governments or health agencies also issued similar travel warnings,[11][12][13] while Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Ecuador, El Salvador, and Jamaica advised women to postpone getting pregnant until more is known about the risks.[12][14] Zika is pronounced /ˈziːkə/ or /ˈzɪkə/.[15][16]

Virology

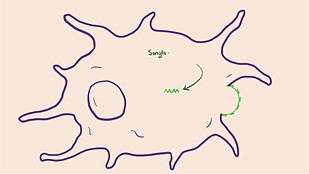

The Zika virus belongs to the Flaviviridae family and the Flavivirus genus, and is thus related to the dengue, yellow fever, Japanese encephalitis, and West Nile viruses. Like other flaviviruses, Zika virus is enveloped and icosahedral and has a nonsegmented, single-stranded, 10 kilobase positive-sense RNA genome. It is most closely related to the Spondweni virus and is one of the two known viruses in the Spondweni virus clade.[17][18][19][20][21]

A positive-sense RNA genome can be directly translated into viral proteins. As in other flaviviruses, such as the similarly sized West Nile virus, the RNA genome encodes seven nonstructural proteins and three structural proteins.[23] One of the structural proteins encapsulates the virus. This protein is the flavivirus envelope glycoprotein, that binds to the endosomal membrane of the host cell to initiate endocytosis.[24] The RNA genome forms a nucleocapsid along with copies of the 12-kDa capsid protein. The nucleocapsid, in turn, is enveloped within a host-derived membrane modified with two viral glycoproteins. Viral genome replication depends on the making of double stranded RNA from the single stranded positive sense RNA (ssRNA(+)) genome followed by transcription and replication to provide viral mRNAs and new ssRNA(+) genomes.[25][26]

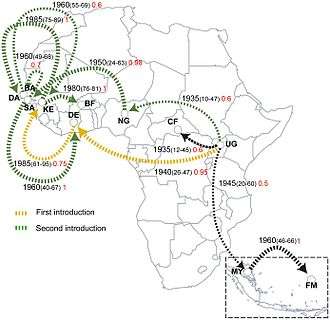

There are two Zika lineages: the African lineage and the Asian lineage.[27] Phylogenetic studies indicate that the virus spreading in the Americas is 89% identical to African genotypes, but is most closely related to the Asian strain that circulated in French Polynesia during the 2013–2014 outbreak.[27][28][29]

Transmission

The vertebrate hosts of the virus were primarily monkeys in a so-called enzootic mosquito-monkey-mosquito cycle, with only occasional transmission to humans. Before the current pandemic began in 2007, Zika "rarely caused recognized 'spillover' infections in humans, even in highly enzootic areas". Infrequently, however, other arboviruses have become established as a human disease and spread in a mosquito–human–mosquito cycle, like the yellow fever virus and the dengue fever virus (both flaviviruses), and the chikungunya virus (a togavirus).[30] Though the reason for the pandemic is unknown, dengue, a related arbovirus that infects the same species of mosquito vectors, is known in particular to be intensified by urbanization and globalization.[31] Zika is primarily spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes,[32] and can also be transmitted through sexual contact[33] or blood transfusions.[34] The basic reproduction number (R0, a measure of transmissibility) of Zika virus has been estimated to be between 1.4 and 6.6.[35]

In 2015, news reports drew attention to the rapid spread of Zika in Latin America and the Caribbean.[36] At that time, the Pan American Health Organization published a list of countries and territories that experienced "local Zika virus transmission" comprising Barbados, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, French Guiana, Guadeloupe, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Martinique, Mexico, Panama, Paraguay, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, Suriname, and Venezuela.[37][38][39] By August 2016, more than 50 countries (list and map) had experienced active (local) transmission of Zika virus.[40]

Mosquito

.png)

Zika is primarily spread by the female Aedes aegypti mosquito, which is active mostly in the daytime.[41][42] The mosquitos must feed on blood in order to lay eggs.[43]:2 The virus has also been isolated from a number of arboreal mosquito species in the Aedes genus, such as A. africanus, A. apicoargenteus, A. furcifer, A. hensilli, A. luteocephalus and A. vittatus, with an extrinsic incubation period in mosquitoes of about 10 days.[20]

The true extent of the vectors is still unknown. Zika has been detected in many more species of Aedes, along with Anopheles coustani, Mansonia uniformis, and Culex perfuscus, although this alone does not incriminate them as a vector.[42]

Transmission by A. albopictus, the tiger mosquito, was reported from a 2007 urban outbreak in Gabon where it had newly invaded the country and become the primary vector for the concomitant chikungunya and dengue virus outbreaks.[44] There is concern for autochthonous infections in urban areas of European countries infested by A. albopictus because the first two cases of laboratory-confirmed Zika infections imported into Italy were reported from viremic travelers returning from French Polynesia.[45]

The potential societal risk of Zika can be delimited by the distribution of the mosquito species that transmit it. The global distribution of the most cited carrier of Zika, A. aegypti, is expanding due to global trade and travel.[46] A. aegypti distribution is now the most extensive ever recorded – across all continents including North America and even the European periphery (Madeira, the Netherlands, and the northeastern Black Sea coast).[47] A mosquito population capable of carrying Zika has been found in a Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D. C., and genetic evidence suggests they survived at least four consecutive winters in the region. The study authors conclude that mosquitos are adapting for persistence in a northern climate.[48] The Zika virus appears to be contagious via mosquitoes for around a week after infection. The virus is thought to be infectious for a longer period of time after infection (at least 2 weeks) when transmitted via semen.[49][50]

Research into its ecological niche suggests that Zika may be influenced to a greater degree by changes in precipitation and temperature than Dengue, making it more likely to be confined to tropical areas. However, rising global temperatures would allow for the disease vector to expand their range further north, allowing Zika to follow.[51]

Sexual

Zika can be transmitted from men and women to their sexual partners.[33][52] As of April 2016 sexual transmission of Zika has been documented in six countries – Argentina, Chile, France, Italy, New Zealand and the United States – during the 2015 outbreak.[8]

Since October 2016, the CDC has advised men who have traveled to an area with Zika should use condoms or not have sex for at least six months after their return, even if they never develop symptoms, because the virus is transmissible in semen.[53]

Pregnancy

The Zika virus can spread by vertical (or "mother-to-child") transmission, during pregnancy or at delivery.[54][6]

Blood transfusion

As of April 2016, two cases of Zika transmission through blood transfusions have been reported globally, both from Brazil,[34] after which the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recommended screening blood donors and deferring high-risk donors for 4 weeks.[55][56] A potential risk had been suspected based on a blood-donor screening study during the French Polynesian Zika outbreak, in which 2.8% (42) of donors from November 2013 and February 2014 tested positive for Zika RNA and were all asymptomatic at the time of blood donation. Eleven of the positive donors reported symptoms of Zika fever after their donation, but only three of 34 samples grew in culture.[57]

Pathogenesis

Zika virus replicates in the mosquito's midgut epithelial cells and then its salivary gland cells. After 5–10 days, the virus can be found in the mosquito’s saliva. If the mosquito’s saliva is inoculated into human skin, the virus can infect epidermal keratinocytes, skin fibroblasts in the skin and the Langerhans cells. The pathogenesis of the virus is hypothesized to continue with a spread to lymph nodes and the bloodstream.[17][58] Flaviviruses generally replicate in the cytoplasm, but Zika antigens have been found in infected cell nuclei.[59]

Zika fever

Zika fever (also known as Zika virus disease) is an illness caused by the Zika virus.[60] Most cases have no symptoms, but when present they are usually mild and can resemble dengue fever.[60][61] Symptoms may include fever, red eyes, joint pain, headache, and a maculopapular rash.[60][62][63] Symptoms generally last less than seven days.[62] It has not caused any reported deaths during the initial infection.[61] Infection during pregnancy causes microcephaly and other brain malformations in some babies.[6][7] Infection in adults has been linked to Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS).[61]

Diagnosis is by testing the blood, urine, or saliva for the presence of Zika virus RNA when the person is sick.[60][62]

Prevention involves decreasing mosquito bites in areas where the disease occurs, and proper use of condoms.[62][64] Efforts to prevent bites include the use of insect repellent, covering much of the body with clothing, mosquito nets, and getting rid of standing water where mosquitoes reproduce.[60] There is no effective vaccine.[62] Health officials recommended that women in areas affected by the 2015–16 Zika outbreak consider putting off pregnancy and that pregnant women not travel to these areas.[62][65] While there is no specific treatment, paracetamol (acetaminophen) and rest may help with the symptoms.[62] Admission to hospital is rarely necessary.[61]

Vaccine development

Effective vaccines have existed for several viruses of the flaviviridae family, namely yellow fever vaccine, Japanese encephalitis vaccine, and tick-borne encephalitis vaccine, since the 1930s, and dengue fever vaccine since the mid-2010s.[66][67][68] World Health Organization (WHO) experts have suggested that the priority should be to develop inactivated vaccines and other non-live vaccines, which are safe to use in pregnant women and those of childbearing age.[69]

As of March 2016, 18 companies and institutions internationally were developing vaccines against Zika but a vaccine was unlikely to be widely available for about ten years.[69][70] In June 2016 the FDA granted the first approval for a human clinical trial for a Zika vaccine.[71]

History

Virus isolation in monkeys and mosquitoes, 1947

The virus was first isolated in April 1947 from a rhesus macaque monkey that had been placed in a cage in the Zika Forest of Uganda, near Lake Victoria, by the scientists of the Yellow Fever Research Institute.[75] A second isolation from the mosquito A. africanus followed at the same site in January 1948.[76] When the monkey developed a fever, researchers isolated from its serum a "filterable transmissible agent" that was named Zika in 1948.[20][77]

First evidence of human infection, 1952

Zika had been known to infect humans from the results of serological surveys in Uganda and Nigeria, published in 1952: Among 84 people of all ages, 50 individuals had antibodies to Zika, and all above 40 years of age were immune.[78] A 1952 research study conducted in India had shown a "significant number" of Indians tested for Zika had exhibited an immune response to the virus, suggesting it had long been widespread within human populations.[79]

It was not until 1954 that the isolation of Zika from a human was published. This came as part of a 1952 outbreak investigation of jaundice suspected to be yellow fever. It was found in the blood of a 10-year-old Nigerian female with low-grade fever, headache, and evidence of malaria, but no jaundice, who recovered within three days. Blood was injected into the brain of laboratory mice, followed by up to 15 mice passages. The virus from mouse brains was then tested in neutralization tests using rhesus monkey sera specifically immune to Zika. In contrast, no virus was isolated from the blood of two infected adults with fever, jaundice, cough, diffuse joint pains in one and fever, headache, pain behind the eyes and in the joints. Infection was proven by a rise in Zika-specific serum antibodies.[78]

Spread in equatorial Africa and to Asia, 1951–1983

From 1951 through 1983, evidence of human infection with Zika was reported from other African countries, such as the Central African Republic, Egypt, Gabon, Sierra Leone, Tanzania, and Uganda, as well as in parts of Asia including India, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan.[20][80] From its discovery until 2007, there were only 14 confirmed human cases of Zika infection from Africa and Southeast Asia.[81]

Micronesia, 2007

In April 2007, the first outbreak outside of Africa and Asia occurred on the island of Yap in the Federated States of Micronesia, characterized by rash, conjunctivitis, and arthralgia, which was initially thought to be dengue, chikungunya, or Ross River disease.[82] Serum samples from patients in the acute phase of illness contained RNA of Zika. There were 49 confirmed cases, 59 unconfirmed cases, no hospitalizations, and no deaths.[83]

2013–2014

Oceania

Between 2013 and 2014, further epidemics occurred in French Polynesia, Easter Island, the Cook Islands, and New Caledonia.[16]

Other cases

On 22 March 2016 Reuters reported that Zika was isolated from a 2014 blood sample of an elderly man in Chittagong in Bangladesh as part of a retrospective study.[84]

Americas, 2015–present

As of early 2016, a widespread outbreak of Zika was ongoing, primarily in the Americas. The outbreak began in April 2015 in Brazil, and has spread to other countries in South America, Central America, North America, and the Caribbean. The Zika virus reached Singapore and Malaysia in Aug 2016.[85] In January 2016, the WHO said the virus was likely to spread throughout most of the Americas by the end of the year;[86] and in February 2016, the WHO declared the cluster of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome cases reported in Brazil – strongly suspected to be associated with the Zika outbreak – a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.[4][87][88][89] It is estimated that 1.5 million people have been infected by Zika in Brazil,[90] with over 3,500 cases of microcephaly reported between October 2015 and January 2016.[91]

A number of countries have issued travel warnings, and the outbreak is expected to significantly impact the tourism industry.[4][92] Several countries have taken the unusual step of advising their citizens to delay pregnancy until more is known about the virus and its impact on fetal development.[14] With the 2016 Summer Olympic Games hosted in Rio de Janeiro, health officials worldwide have voiced concerns over a potential crisis, both in Brazil and when international athletes and tourists, who may be unknowingly infected, return home and possibly spread the virus. Some researchers speculate that only one or two tourists may be infected during the three week period, or approximately 3.2 infections per 100,000 tourists.[93] In November 2016, the World Health Organization declared that the Zika virus was no longer a global emergency.[94]

References

- ↑ Goldsmith, Cynthia (18 March 2005). "Zika Virus". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ Sirohi, D.; Chen, Z.; Sun, L.; et al. (31 March 2016). "The 3.8 Å resolution cryo-EM structure of Zika virus". Science. 352 (6284): 467–70. Bibcode:2016Sci...352..467S. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5316. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 27033547.

- 1 2 3 Malone, Robert W.; Homan, Jane; Callahan, Michael V.; et al. (2 March 2016). "Zika Virus: Medical Countermeasure Development Challenges". PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (3): e0004530. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004530. ISSN 1935-2735.

- 1 2 3 4 Sikka, Veronica; Chattu, Vijay Kumar; Popli, Raaj K.; et al. (11 February 2016). "The emergence of zika virus as a global health security threat: A review and a consensus statement of the INDUSEM Joint working Group (JWG)". Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 8 (1): 3–15. doi:10.4103/0974-777X.176140. ISSN 0974-8245.

- 1 2 "Symptoms, Diagnosis, & Treatment". Zika virus. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 3 March 2016. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 Rasmussen, Sonja A.; Jamieson, Denise J.; Honein, Margaret A.; Petersen, Lyle R. (13 April 2016). "Zika Virus and Birth Defects — Reviewing the Evidence for Causality". New England Journal of Medicine. 374: 1981–1987. doi:10.1056/NEJMsr1604338.

- 1 2 "CDC Concludes Zika Causes Microcephaly and Other Birth Defects". CDC. 13 April 2016. Retrieved 14 April 2016.

- 1 2 "Zika Virus Microcephaly And Guillain–Barré Syndrome Situation Report" (PDF). World Health Organization. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- ↑ "Zika Virus in the Caribbean". Travelers' Health: Travel Notices. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 January 2016.

- ↑ Petersen, Emily E.; Staples, J. Erin; Meaney-Delman, Dana; et al. (22 January 2016). "Interim Guidelines for Pregnant Women During a Zika Virus Outbreak — United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (2): 30–33. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6502e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 26796813.

- ↑ "Zika virus: Advice for those planning to travel to outbreak areas". ITV Report. ITV News. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- 1 2 "Pregnant Irish women warned over Zika virus in central and South America". RTÉ News. 22 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "Zika: Olympics plans announced by Rio authorities". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. 24 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

The Rio de Janeiro authorities have announced plans to prevent the spread of the Zika virus during the Olympic Games later this year. ... The US, Canada and EU health agencies have issued warnings saying pregnant women should avoid traveling to Brazil and other countries in the Americas which have registered cases of Zika.

- 1 2 "Zika virus triggers pregnancy delay calls". BBC News. 23 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- ↑ "How to pronounce Zika". HowToPronounce.com.

- 1 2 "Etymologia: Zika Virus". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 20 (6): 1090. June 2014. doi:10.3201/eid2006.ET2006. PMC 4036762

. PMID 24983096.

. PMID 24983096. - 1 2 Knipe, David M.; Howley, Peter M. (2007). Fields Virology (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 1156, 1199. ISBN 978-0-7817-6060-7.

- ↑ Faye, Oumar; Freire, Caio C. M.; Iamarino, Atila; Faye, Ousmane; de Oliveira, Juliana Velasco C.; Diallo, Mawlouth; Zanotto, Paolo M. A.; Sall, Amadou Alpha; Bird, Brian (9 January 2014). "Molecular Evolution of Zika Virus during Its Emergence in the 20th Century". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (1): e2636. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002636. PMC 3888466

. PMID 24421913.

. PMID 24421913. - ↑ Cao-Lormeau, V. M.; Roche, C.; Teissier, A.; Robin, E.; Berry, A. L.; Mallet, H. P.; Sall, A. A.; Musso, D. (June 2014). "Zika virus, French polynesia, South pacific, 2013.". Emerg Infect Dis. 20 (6): 1085–6. doi:10.3201/eid2006.140138. PMC 4036769

. PMID 24856001.

. PMID 24856001. - 1 2 3 4 Hayes, Edward B. (September 2009). "Zika Virus Outside Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 15 (9): 1347–1350. doi:10.3201/eid1509.090442. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 2819875

. PMID 19788800.

. PMID 19788800. - ↑ Kuno, G.; Chang, G.-J. J. (1 January 2007). "Full-length sequencing and genomic characterization of Bagaza, Kedougou, and Zika viruses". Archives of Virology. 152 (4): 687–696. doi:10.1007/s00705-006-0903-z. PMID 17195954.

- ↑ Goodsell, D. S. "Zika Virus". RCSB Protein Data Bank. Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB). doi:10.2210/rcsb_pdb/mom_2016_5. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- ↑ Cox, Bryan D.; Stanton, Richard A.; Schinazi, Raymond F. (2016-06-13). "Predicting Zika virus structural biology: Challenges and opportunities for intervention". Antiviral Chemistry & Chemotherapy. doi:10.1177/2040206616653873. ISSN 2040-2066. PMID 27296393.

- ↑ Dai, Lianpan (11 May 2016). "Structures of the Zika Virus Envelope Protein and Its Complex with a Flavivirus Broadly Protective Antibody". Cell Host & Microbe. 19 (5). doi:10.1016/j.chom.2016.04.013. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- ↑ "ViralZone: Zika virus (strain Mr 766)". viralzone.expasy.org. SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ↑ Pierson, T. C.; Diamond, M. S. (April 2012). "Degrees of maturity: The complex structure and biology of flaviviruses". Current Opinion in Virology. 2 (2): 168–175. doi:10.1016/j.coviro.2012.02.011. PMC 3715965

. PMID 22445964.

. PMID 22445964. - 1 2 Enfissi, Antoine; Codrington, John; Roosblad, Jimmy; et al. (16 January 2016). "Zika virus genome from the Americas". Lancet. 387 (10015): 227–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00003-9. PMID 26775124.

- ↑ Zanluca, Camila; Melo, Vanessa Campos Andrade de; Mosimann, Ana Luiza Pamplona; et al. (June 2015). "First report of autochthonous transmission of Zika virus in Brazil". Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 110 (4): 569–572. doi:10.1590/0074-02760150192. ISSN 1678-8060. PMC 4501423

. PMID 26061233.

. PMID 26061233. - 1 2 Lanciotti, Robert S.; Lambert, Amy J.; Holodniy, Mark; et al. (2016). "Phylogeny of Zika Virus in Western Hemisphere, 2015". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 22 (5): 933–5. doi:10.3201/eid2205.160065. ISSN 1080-6040. PMC 4861537

. PMID 27088323.

. PMID 27088323. - ↑ Fauci, Anthony S.; Morens, David M. (14 January 2016). "Zika Virus in the Americas – Yet Another Arbovirus Threat". New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (2): 601–4. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1600297. PMID 26761185.

- ↑ Gubler, D. J. (2011). "Dengue, Urbanization and Globalization: The Unholy Trinity of the 21(st) Century". Trop Med Health. 39: 3–11. doi:10.2149/tmh.2011-S05. PMC 3317603

. PMID 22500131.

. PMID 22500131. - ↑ "Zika virus found in common house mosquitoes". Retrieved 23 July 2016.

- 1 2 Oster, Alexandra M.; Russell, Kate; Stryker, Jo Ellen; et al. (1 April 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (12): 323–325. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6512e3. PMID 27032078.

- 1 2 Vasquez, Amber M.; Sapiano, Mathew R.P.; Basavaraju, Sridhar V.; et al. (2016). "Survey of Blood Collection Centers and Implementation of Guidance for Prevention of Transfusion-Transmitted Zika Virus Infection — Puerto Rico, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (14): 375–378. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6514e1. ISSN 0149-2195. PMID 27078190.

- ↑ "Science Magazine - 12 August 2016 - 27". www.sciencemagazinedigital.org. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ Moloney, Anastasia (22 January 2016). "FACTBOX – Zika virus spreads rapidly through Latin America, Caribbean". Thomson Reuters Foundation News. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Cristina (18 January 2016). "As the Zika virus spreads, PAHO advises countries to monitor and report birth anomalies and other suspected complications of the virus". Media Center. Pan American Health Organization. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Cristina (2 February 2016). "PAHO Statement on Zika Virus Transmission and Prevention". PAHO.org. Pan American Health Organization.

- ↑ "5 things you need to know about Zika". CNN. 24 February 2016.

- ↑ "Zika Virus". All Countries & Territories with Active Zika Virus Transmission. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ Abushouk, AI; Negida, A; Ahmed, H (3 October 2016). "An updated review of Zika virus.". Journal of clinical virology : the official publication of the Pan American Society for Clinical Virology. 84: 53–58. PMID 27721110.

- 1 2 Ayres, Constância F J (4 February 2016). "Identification of Zika virus vectors and implications for control". The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 16 (3): 278–279. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00073-6. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 26852727.

- ↑ Division of Vector-Borne Diseases, Dengue Branch. "Dengue and the Aedes aegypti mosquito" (PDF). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Charrel, Remi; Grard, Gilda; Caron, Mélanie; et al. (6 February 2014). "Zika Virus in Gabon (Central Africa) – 2007: A New Threat from Aedes albopictus?". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 8 (2): e2681. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0002681. ISSN 1935-2735. PMC 3916288

. PMID 24516683.

. PMID 24516683. - ↑ Zammarchi, Lorenzo; Stella, Giulia; Mantella, Antonia; et al. (February 2015). "Zika virus infections imported to Italy: Clinical, immunological and virological findings, and public health implications". Journal of Clinical Virology. 63: 32–35. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2014.12.005. ISSN 1386-6532. PMID 25600600.

- ↑ Kraemer, Moritz U. G.; Sinka, Marianne E.; Duda, Kirsten A.; et al. (7 July 2015). "The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus". ELife. 4: e08347. doi:10.7554/eLife.08347. PMC 4493616

. PMID 26126267.

. PMID 26126267. - ↑ "Aedes aegypti". Health Topics: Vectors: Mosquitos. European Centre for Disease Protection and Control. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ Craig, Sarah; Collins, Brittany (26 January 2016). "Mosquitoes capable of carrying Zika virus found in Washington, D.C.". Notre Dame News. University of Notre Dame.

- ↑ "Zika outbreak: What you need to know". BBC News. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ "How to Avoid Mosquito Bites in Florida". 10 June 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Colin Carlson, Eric Dougherty, Wayne Getz. An ecological assessment of the pandemic threat of Zika virus. bioRxiv 040386; doi:10.1101/040386

- ↑ "WHO chief going to the Olympics, says Zika risk low". www.msn.com. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

According to Margaret Chan, the director of the WHO, 'Of course, we also have learnt from the latest evidence it's not just infected men who can pass the disease to their sex partners. There was a case of a lady passing the disease to a man, so it can go both directions.'

- ↑ Petersen, Emily E.; Meaney-Delman, Dana; Neblett-Fanfair, Robyn; Havers, Fiona; Oduyebo, Titilope; Hills, Susan L.; Rabe, Ingrid B.; Lambert, Amy; Abercrombie, Julia; Martin, Stacey W.; Gould, Carolyn V.; Oussayef, Nadia; Polen, Kara N.D.; Kuehnert, Matthew J.; Pillai, Satish K.; Petersen, Lyle R.; Honein, Margaret A.; Jamieson, Denise J.; Brooks, John T. (7 October 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Preconception Counseling and Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus for Persons with Possible Zika Virus Exposure — United States, September 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (39): 1077–1081. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6539e1.

- ↑ "CDC Zika: Transmission". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 15 April 2016. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- ↑ "Recommendations for Donor Screening, Deferral, and Product Management to Reduce the Risk of Transfusion- Transmission of Zika Virus" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. February 2016.

- ↑ "Zika virus infection outbreak, Brazil and the Pacific region" (PDF). Rapid Risk Assessments. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 May 2015. pp. 4–5. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Musso, D; Nhan, T.; Robin, E.; et al. (10 April 2014). "Potential for Zika virus transmission through blood transfusion demonstrated during an outbreak in French Polynesia, November 2013 to February 2014". Eurosurveillance. 19 (14). PMID 24739982.

- ↑ Chan, Jasper F. W.; Choi, Garnet K. Y.; Yip, Cyril C. Y.; et al. (2016). "Zika fever and congenital Zika syndrome: An unexpected emerging arboviral disease". Journal of Infection. 72 (5): 507–24. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2016.02.011. ISSN 0163-4453. PMID 26940504.

- ↑ Buckley, A.; Gould, E. A. (1988). "Detection of Virus-specific Antigen in the Nuclei or Nucleoli of Cells Infected with Zika or Langat Virus". Journal of General Virology. 69 (8): 1913–1920. doi:10.1099/0022-1317-69-8-1913. ISSN 0022-1317. PMID 2841406.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Zika virus". World Health Organization. January 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Factsheet for health professionals". Health topics: Zika virus infection. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Retrieved 22 December 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Chen, Lin H.; Hamer, Davidson H. (2016). "Zika Virus: Rapid Spread in the Western Hemisphere". Annals of Internal Medicine. 164 (9): 613. doi:10.7326/M16-0150. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 26832396.

- ↑ Musso, D.; Nilles, E. J.; Cao-Lormeau, V.-M. (2014). "Rapid spread of emerging Zika virus in the Pacific area". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20 (10): O595–6. doi:10.1111/1469-0691.12707. PMID 24909208.

- ↑ Oster, Alexandra M.; Russell, Kate; Stryker, Jo Ellen; Friedman, Allison; Kachur, Rachel E.; Petersen, Emily E.; Jamieson, Denise J.; Cohn, Amanda C.; Brooks, John T. (1 April 2016). "Update: Interim Guidance for Prevention of Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus — United States, 2016". MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 65 (12): 323–325. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6512e3. PMID 27032078.

- ↑ "Brazil warns against pregnancy due to spreading virus". CNN. 24 December 2015. Retrieved 24 December 2015.

- ↑ "Dengue vaccine research". Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. World Health Organization. 14 December 2015.

- ↑ Bennett, John E.; Dolin, Raphael; Blaser, Martin J. (2014). Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1881. ISBN 978-1-4557-4801-3.

- ↑ Maron, Dina Fine (30 December 2016). "First Dengue Fever Vaccine Gets Green Light in 3 Countries". Scientific American. Springer Nature. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- 1 2 "WHO and experts prioritize vaccines, diagnostics and innovative vector control tools for Zika R&D". World Health Organization. 9 March 2016. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ↑ Cook, James (27 January 2016). "Zika virus: US scientists say vaccine '10 years away'". BBC News. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ↑ Sagonowsky, Eric (21 June 2016). "Inovio set for first Zika vaccine human trial". fiercepharma.com. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Geographic Distribution". Zika Virus. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Gatherer, Derek; Kohl, Alain (18 December 2015). "Zika virus: a previously slow pandemic spreads rapidly through the Americas". Journal of General Virology. 97 (2): 269–273. doi:10.1099/jgv.0.000381. PMID 26684466.

- ↑ "Zika virus in the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- ↑ =Cohen, Jon (8 February 2016). "Zika's long, strange trip into the limelight". Science. American Association for the Advancement of Science. Retrieved 10 February 2016.

- ↑ Haddow, A. D.; Schuh, A. J.; Yasuda, C. Y.; et al. (2012). "Genetic Characterization of Zika Virus Strains: Geographic Expansion of the Asian Lineage". PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 6 (2): e1477. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0001477. PMC 3289602

. PMID 22389730.

. PMID 22389730. - ↑ "Zika Virus (06): Overview 2016-02-09 19:58:3 Archive Number: 20160209.4007411". Pro-MED-mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases.

- 1 2 Dick, G. W. A.; Kitchen, S. F.; Haddow, A. J. (September 1952). "Zika Virus (I). Isolations and serological specificity". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 46 (5): 509–520. doi:10.1016/0035-9203(52)90042-4. ISSN 0035-9203. PMID 12995440.

- ↑ Rowlatt, Justin (2 February 2016). "Why Asia should worry about Zika too". BBC News. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ "Timeline – Zika's origin and global spread". Fox News Channel. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- ↑ Ramzy, Austin (10 February 2016). "Experts Study Zika's Path From First Outbreak in Pacific". The New York Times. Hong Kong. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ↑ Altman, L. K. (3 July 2007). "Little-Known Virus Challenges a Far-Flung Health System". The New York Times.

- ↑ Duffy, Mark R.; Chen, Tai-Ho; Hancock, W. Thane; et al. (11 June 2009). "Zika Virus Outbreak on Yap Island, Federated States of Micronesia". New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (24): 2536–2543. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0805715. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 19516034.

- ↑ "Bangladesh Confirms First Case of Zika Virus". Newsweek. 22 March 2016. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ↑ "Zika Virus in Singapore". CDC. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ "WHO sees Zika outbreak spreading through the Americas". Reuters. 25 January 2016. Retrieved 25 January 2016.

- ↑ "WHO Director-General summarizes the outcome of the Emergency Committee regarding clusters of microcephaly and Guillain–Barré syndrome". World Health Organization. 1 February 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Roberts, Michelle (1 February 2016). "Zika-linked condition: WHO declares global emergency". BBC News. Retrieved 1 February 2016.

- ↑ Pearson, Michael (2 February 2016). "Zika virus sparks 'public health emergency'". CNN. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ↑ Boadle, Anthony; Brown, Tom; Orr, Bernard (18 February 2016). "U.S., Brazil researchers join forces to battle Zika virus". Brasilia. Reuters. Retrieved 4 March 2016.

- ↑ "Microcephaly in Brazil potentially linked to the Zika virus epidemic, ECDC assesses the risk". News and Media. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. 25 November 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2016.

- ↑ Kiernan, Paul; Jelmayer, Rogerio (3 February 2016). "Zika Fears Imperil Brazil's Tourism Push". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- ↑ Belluz, Julia (26 May 2016). "Rio Olympics 2016: why athletes and fans aren't likely to catch Zika.". Vox. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ↑ "World Health Organization declares end of Zika emergency". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2016-11-18.

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website http://www.cdc.gov/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website http://www.cdc.gov/.

External links

- Zika virus – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- World Health Organization Zika virus Fact Sheet

- Zika virus illustrations, 3D model, and animation

- ViralZone: Zika virus (strain Mr 766)

- Zika virus at NCBI Taxonomy Browser

- Schmaljohn, Alan L.; McClain, David (1996). "54. Alphaviruses (Togaviridae) and Flaviviruses (Flaviviridae)". In Baron, Samuel. Medical Microbiology (4th ed.). ISBN 0-9631172-1-1. NBK7633.

- Animation on Zika from Scientific Animations Without Borders and the World Health Organization (WHO)